Summary

Although imaging the live Trypanosoma cruzi parasite is a routine technique in most laboratories, identification of the parasite in infected tissues and organs has been hindered by their intrinsic opaque nature. We describe a simple method for in vivo observation of live single‐cell Trypanosoma cruzi parasites inside mammalian host tissues. BALB/c or C57BL/6 mice infected with DsRed‐CL or GFP‐G trypomastigotes had their organs removed and sectioned with surgical blades. Ex vivo organ sections were observed under confocal microscopy. For the first time, this procedure enabled imaging of individual amastigotes, intermediate forms and motile trypomastigotes within infected tissues of mammalian hosts.

Keywords: Trypanosoma cruzi, live imaging, ex vivo, trypomastigote, amastigote, epimastigote‐like

Introduction

Since the discovery of Chagas' disease in 1909 (Chagas, 1909), major leaps in Trypanosoma cruzi biology have been achieved and have resulted in gradually improving advanced techniques for direct parasite observation (Florentino et al., 2014). Optical and electron microscopy (De Souza, 2008) are the most commonly used advanced techniques. Early in vitro optical microscopy images of cultured cells infected with T. cruzi were first reported by Meyer et al. (1948). In the now classical movie sequence, Meyer and Barasa described its life cycle stages in mammalian cells: invasion, intracellular growth and differentiation and cell egress (Meyer et al., 1942). Since then, imaging of live T. cruzi in its different evolutive forms has become routine in research laboratories. Detailed information has been acquired using modern techniques, such as multidimensional confocal and electron microscopy (Florentino et al., 2014).

Live imaging is emerging as a powerful tool to examine how parasites interact with host cells and tissues, as well as their vectors (Amino et al., 2005). Bioluminescence detection of luciferase‐transfected pathogens have enabled researchers to identify infection loci and disease development in real time in experimental animal models (Amino et al., 2005). Plasmodium spp was the first protozoan parasite to be successfully imaged in intravital observations at the single‐cell level (Amino et al., 2005). Using bioluminescence, T. cruzi has also been tracked in infected mice (Umekita et al., 2001, Hyland et al., 2008, Henriques et al., 2014, Lewis et al., 2014) and vectors (Henriques et al., 2012). However, intravital microscopy is limited by tissue penetration depths of up to a few hundred microns and blurring due to the overlaying connective tissue. To circumvent these limitations, some strategies can be adopted such as extracting more superficial tissues in the area of interest: for example, thinning skull without removing it and image intravascular and extravascular T. brucei through the remaining bone (Myburgh et al., 2013). However, in order to image deeper areas, ex vivo explants of tissues and organs have been used as a tool to monitor cell migration and distribution (Bajénoff et al., 2008, Mort et al., 2014). Here, we describe a simple method to detect individual T. cruzi forms millimetres inside infected tissues and organs: slicing a specimen to gain access to the interior, then imaging ex vivo slices.

Results and Discussion

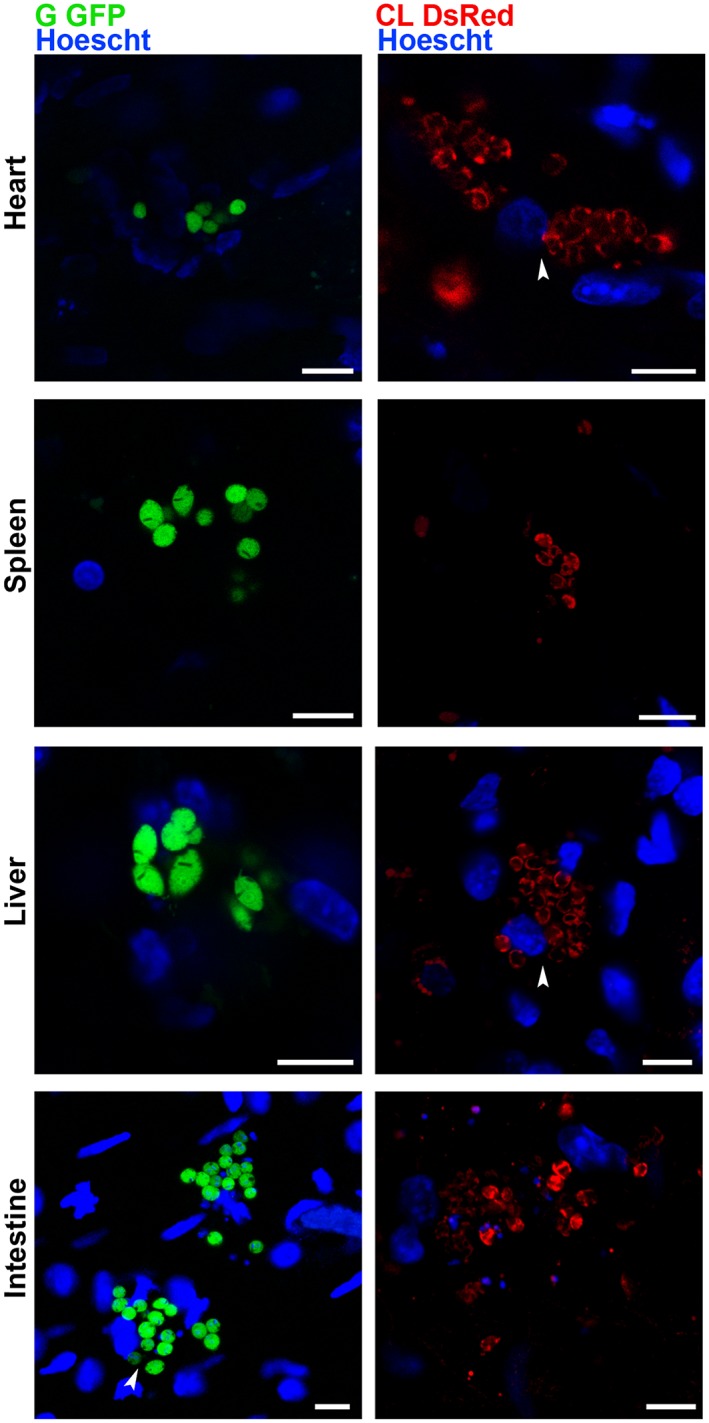

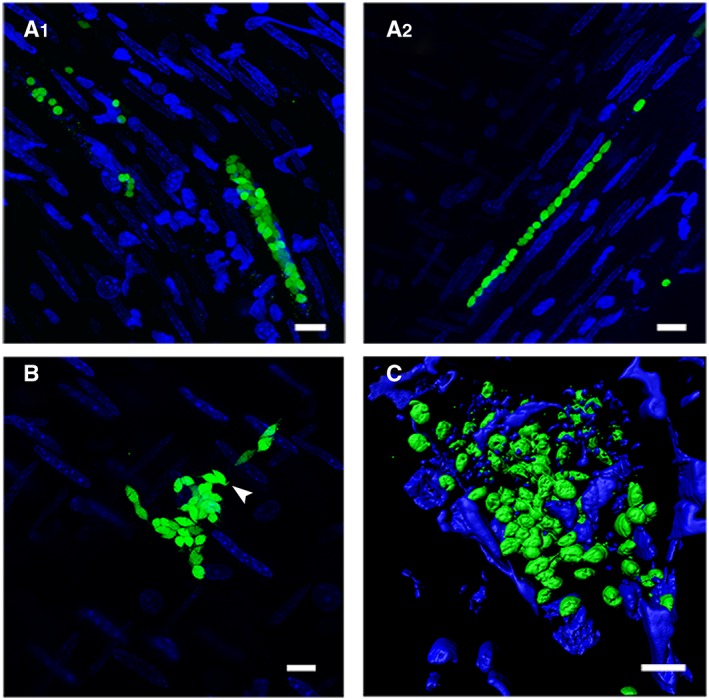

The BALB/c or C57‐BL/6 mice infected with transfected T. cruzi trypomastigotes were sacrificed at the acute phase of infection (8 days). After organ removal and sectioning, slices were placed in a coverslip bottom dish, immersed in culture medium and imaged in a confocal microscope equipped with an environmentally controlled stage (Fig. S1). Amastigote nests of live G‐GFP parasites were visualized in the following selected organs: spleen, heart, intestine and liver (Fig. 1). DsRed‐CL amastigotes were also detected in these tissues (Fig. 1). GFP and DsRed labelling presented different fluorescence intensities (Fig. 1). Because the amastigotes were mostly immotile, optical sectioning through nests revealed the disposition of parasites and surrounding Hoechst‐labelled nuclei (Fig. 1, arrowheads). Tridimensional images of some parasite nests also revealed intermediate flagellated forms among amastigotes (Fig. 2B, arrowhead). Live intermediate forms were also recorded in the nests within the intestinal tissue (Fig. 2B, Movie S1).

Figure 1.

Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes imaged at the single‐cell level within nests in live tissues. The sectioned heart, spleen, liver and intestine of the mice infected with G GFP or CL DsRed trypomastigotes (8 dpi) were maintained ex vivo in dishes with culture medium and observed by confocal microscopy. Amastigote nests were found in all the organs. Arrowheads point to parasites surrounding Hoechst‐labelled nuclei. Bars = 10 µm.

Figure 2.

Trypanosoma cruzi (G‐GFP) epimastigote‐like and amastigotes form nests with distinct morphologies. A. Unconventional linear amastigote arrays imaged in intestine sections of mice infected with G‐GFP parasites. The approximate nest dimensions on the right: 59 µm (x, y) × 15 µm (z); left: 117 µm (x, y) × 24 µm (z). B. T. cruzi epimastigote‐like intermediate forms in an intestine section of a G‐GFP‐infected mice. The approximate nest dimensions: 56 µm (x, y) × 10 µm (z). C. Three‐dimensional reconstruction of a G‐GFP amastigote heart nest. Arrowhead points to flagellated intermediate forms. The approximate nest dimensions: 38 µm × 72 µm × 15 µm. Bars = 10 µm.

Although nest morphology varied in different sections and tissues (Fig. 1), single‐cell linear arrangements of amastigotes formed unusually shaped agglomerates within the intestinal tissue (Fig. 2A), which can indicate nests in muscular layer. Nests containing highly motile trypomastigotes were found in the spleen and liver (Movies S2, S3). Parasites were imaged at the single‐cell level within nests ranging from 10 up to almost 200 µm wide, for up to 8 h (Movie S4). Highly motile trypomastigotes were found sometimes free in the tissues or sharing nests with other trypomastigotes, amastigotes or intermediate forms (Movie S1). It is possible, however, that trypomastigotes are freed as a consequence of blade‐promoted nest disruption.

To our knowledge, this is the first description of T. cruzi imaging from inside infected tissues at the single‐cell level. This method can provide, with good resolution, new information about parasite behaviour inside host tissues and the nature of neighbouring cells and elucidate infection mechanisms. A similar technique has brought relevant data on Toxoplasma gondii intestinal infection (Coombes et al., 2013). Therefore, the tool described here could be applied to examine areas with different depths in organs and tissues infected with other several pathogens, for instance, T. gondii within brain cysts or Leishmania chagasi inside liver macrophages.

Experimental Procedures

Parasites

Transfected G (Tc I, GFP) (Cruz et al., 2012) and CL (TcVI, DsRed) (Brener et al., 1963) parasite strains were cycled as epimastigotes in LIT medium or Vero cell culture monolayers as trypomastigotes, as previously described (Cruz et al., 2012). Trypanosoma expression construct (pTREX‐DsRm) containing DsRed fluorescent protein was prepared using standard protocols. Briefly, an open reading frame coding the monomeric variant of DsRed was amplified by the polymerase chain reaction using oligonucleotides DsRmBF (5′‐ggatccATGGACAACACCGAGGAC‐3′) and DsRmHR (5′‐aagcttCTACTGGGAGCCGGAGTG‐3′) containing BamHI and HindIII restriction sites respectively (lower case). Amplicons were resolved on agarose gels, purified, cloned into pGEM®‐T Easy vector (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI, USA) and sequenced for confirmation. Clones with the correct sequence were digested with BamHI and HindIII restriction enzymes. The insert was sub‐cloned into pTEX vector (Kelly et al., 1992), rendering the pTEX‐DsRm construct. Finally, the pTEX‐DsRm plasmid was digested with XbaI and XhoI restriction enzymes, and the insert was sub‐cloned into pTREX vector (Vazquez et al., 1999) previously digested with the aforementioned enzymes. Parasite transfections were performed using a Gene Pulser Xcell electroporation system (Bio‐Rad) as described by (Ramirez et al., 2000). Briefly, 4 × 107 epimastigotes and 10 µg of plasmid DNA were mixed in 0.4 cm gap electroporation cuvettes. Samples were submitted to two consecutive pulses of 450 V and 500 μF. Parasites were transferred to 5 mL of fresh LIT medium and incubated at 26 °C for 48 h before selecting for transfected parasites with 200 µg/mL of G418. The G strain has a low virulence in mice and generates undetectable parasitemia. Parasites appears 5–8 days post‐infection in the liver (Cruz et al., 2012). CL parasites are more infective and give rise to widespread acute murine infections (Lenzi et al., 1996).

Animal infections and tissue imaging

All experiments involving animal work were conducted under the Brazilian National Committee on Ethics Research ethic guidelines, which are in accordance with international standards (CIOMS/OMS, 1985). The Committee on Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo approved the protocol described in this study (permit number: CEUA 33710910/14). During experimental procedures, all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering. BALB/c or C57‐BL/6 mice were infected using an intraperitoneal injection of tissue culture‐derived GFP‐transfected G strain (Cruz et al., 2012) or Ds‐Red‐transfected CL‐strain trypomastigotes. Mice with parasitemia were monitored every 1 days as previously described (Brener, 1962). One day after parasitemia peaked (around day 8 pi for the CL strain and extended for all experiments), animals were sacrificed, and organs were removed. Organs were placed onto a cold paraffin surface. Slices were cut with a sandwich of GEM single‐edge blades and immersed in phosphate‐buffered saline containing 1 μM Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) to label nuclei. Samples were then cyanoacrylate glued to coverslips or inverted onto glass‐bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA) in RPMI‐1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life Technologies, Brazil). Ex vivo specimens were transferred to a stage top incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2 with controlled humidity (Tokai Hit, Japan) on a Leica SP5 TS confocal microscope. Samples were imaged with a 63 × 1.40 oil‐immersion objective using the resonant scanner (8000 Hz) mode for the heart, liver, spleen and intestine (Fig. S1).

Supporting information

Fig. S1.Experimental procedure for ex vivo organ imaging. (A) Organs are placed onto a cold paraffin surface and slices cut with a sandwich of GEM single edge blades. Posterior immersion in cold PBS containing 1 μM Hoechst 33342 to label nuclei is not shown. (B) Samples are cyanoacrylate glued to coverslips and inverted onto glass‐bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, USA) in culture medium. In (B’) an alternative method is presented in which samples are glued to a starched fabric mesh. (C) Ex vivo specimens are placed in a stage top incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 with controlled humidity on a confocal microscope.

Movie S1. Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote‐like forms in the intestine. Flagellated epimastigote‐like forms observed in an ex vivo intestine section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 27 seconds with one second intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 56 µm (x, y) x 10 µm (z).

Movie S2. Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote nest in the liver. Actively moving trypomastigotes observed in an ex vivo liver section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 90 minutes with one minute intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 149 µm x 163 µm.

Movie S3. Trypanosoma cruzi forms moving inside nest in the liver. Actively moving trypomastigotes observed in an ex vivo liver section of a CL‐DsRed infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 1 minute with one second intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 50 µm x 22 µm.

Movie S4.Long‐time imaging of Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes nest in the liver. Three‐dimensional reconstruction of amastigote forms observed in an ex vivo liver section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 11 hours with thirty minutes intervals. The nest was imaged for 8 hours until fading began. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor).

Supporting info item

Acknowledgements

The financial support from the Brazilian agencies FAPESP (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo), CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico) and Capes (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior) is acknowledged. BLF is a scholar from FAPESP (no. 2014/21338‐2) and RAM is a fellow from CNPq. We are grateful to Éden Ramalho Ferreira for his help with the Imaris program and Alexis Bonfim‐Melo for plasmids and support. We thank Wiley for English editing services. The authors have no conflict of interest.

Ferreira, B. L. , Orikaza, C. M. , Cordero, E. M. , and Mortara, R. A. (2016) Trypanosoma cruzi: single cell live imaging inside infected tissues. Cellular Microbiology, 18: 779–783. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12553.

References

- Amino, R. , Menard, R. , and Frischknecht, F. (2005) In vivo imaging of malaria parasites – recent advances and future directions. Curr Opin Microbiol 8: 407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajénoff, M. , Glaichenhaus, N. , and Germain, R.N. (2008) Fibroblastic reticular cells guide T lymphocyte entry into and migration within the splenic T cell zone. J Immunol 181: 3947–3954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener, Z. (1962) Therapeutic activity and criterion of cure in mice experimentally infected with Trypanosoma cruzi . Rev Ins Med Trop São Paulo 4: 389–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener, Z. , and Chiari, E. (1963) Variações morfológicas observadas em diferentes amostras de Trypanosoma cruzi . Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 5: 220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagas, C. (1909) Nova tripanozomíase humana. Estudos sobre a morfologia e o ciclo evolutivo do Schizotrypanum n.gen, n. sp., agente etiológico de nova entidade mórbida do homem. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (Rio de Janeiro) 1: 159–218. [Google Scholar]

- Coombes, J.L. , Charsar, B.A. , Han, S.J. , Halkias, J. , Chan, S.W. , Koshy, A.A. , et al. (2013) Motile invaded neutrophils in the small intestine of Toxoplasma gondii‐infected mice reveal a potential mechanism for parasite spread. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110: 1913–1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, M.C. , Souza‐Melo, N. , da Silva, C.V. , DaRocha, W.D. , Bahia, D. , Araujo, P.R. , et al. (2012) Trypanosoma cruzi: role of delta‐amastin on extracellular amastigote cell invasion and differentiation. PLoS One 7: e51804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza, W. (2008) Electron microscopy of trypanosomes – a historical view. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz (Rio de Janeiro) 103: 313–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florentino, P.T. , Real, F. , Bonfim‐Melo, A. , Orikaza, C.M. , Ferreira, E.R. , Pessoa, C.C. , et al. (2014) An historical perspective on how advances in microscopic imaging contributed to understanding the Leishmania spp and Trypanosoma cruzi host–parasite relationship. Biomed Res Int 2014 565291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, C. , Castro, D.P. , Gomes, L.H.F. , Garcia, E.S. , and de Souza, W. (2012) Bioluminescent imaging of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in Rhodnius prolixus . Parasites & Vectors 5: 214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, C. , Henriques‐Pons, A. , Meuser‐Batista, M. , Ribeiro, A.S. , and de Souza, W. (2014) In vivo imaging of mice infected with bioluminescent Trypanosoma cruzi unveils novel sites of infection. Parasites & Vectors 7: 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K.V. , Asfaw, S.H. , Olson, C.L. , Daniels, M.D. , and Engman, D.M. (2008) Bioluminescent imaging of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Int J Parasitol 38: 1391–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, J.M. , Ward, H.M. , Miles, M.A. , and Kendall, G. (1992) A shuttle vector which facilitates the expression of transfected genes in Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania . Nucleic Acids Res 20: 3963–3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi, H.L. , Oliveira, D.N. , Lima, M.T. , and Gattass, C.R. (1996) Trypanosoma cruzi: paninfectivity of CL strain during murine acute infection. Exp Parasitol 84: 16–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, M.D. , Fortes Francisco, A. , Taylor, 3. , Burrell‐Saward, H. , McLatchie, A.P. , Miles, M.A. , and Kelly, J.M. (2014) Bioluminescence imaging of chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infections reveals tissue‐specific parasite dynamics and heart disease in the absence of locally persistent infection. Cell Microbiol 16: 1285–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, H. , and Barasa, A. (1942) Life cycle of Schizotrypanum cruzi in tissue cultures. In http://www.itarget.com.br/newclients/sbpz.org.br/2011/extra/download/cruzi1.mpg

- Meyer, H. , and Xavier de Oliveira, M. (1948) Cultivation of Trypanosoma cruzi in tissue cultures: a four‐year study. Parasitology 39: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort, R.L. , Keighren, M. , Hay, L. , and Jackson, I.J. (2014) Ex vivo culture of mouse embryonic skin and live‐imaging of melanoblast migration. J Vis Exp. DOI: 10.3791/51352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myburgh, E. , Coles, J.A. , Ritchie, R. , Kennedy, P.G. , McLatchie, A.P. , Rodgers, J. , et al. (2013) In vivo imaging of trypanosome–brain interactions and development of a rapid screening test for drugs against CNS stage trypanosomiasis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, M.I. , Yamauchi, L.M. , de Freitas, L.H. , Uemura, H., Jr. , and Schenkman, S. (2000) The use of the green fluorescent protein to monitor and improve transfection in Trypanosoma cruzi . Mol Biochem Parasitol 111: 235–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umekita, L.F. , Lopes‐Ferreira, M. , Piazza, R.M. , Umezawa, E.S. , Nascimento, M.S. , Farsky, S.H. , and Mota, I. (2001) Alterations of the microcirculatory network during the clearance of epimastigote forms of Trypanosoma cruzi: an intravital microscopic study. J Parasitol 87: 114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, M.P. , and Levin, M.J. (1999) Functional analysis of the intergenic regions of TcP2beta gene loci allowed the construction of an improved Trypanosoma cruzi expression vector. Gene 239: 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1.Experimental procedure for ex vivo organ imaging. (A) Organs are placed onto a cold paraffin surface and slices cut with a sandwich of GEM single edge blades. Posterior immersion in cold PBS containing 1 μM Hoechst 33342 to label nuclei is not shown. (B) Samples are cyanoacrylate glued to coverslips and inverted onto glass‐bottom dishes (MatTek Corporation, USA) in culture medium. In (B’) an alternative method is presented in which samples are glued to a starched fabric mesh. (C) Ex vivo specimens are placed in a stage top incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2 with controlled humidity on a confocal microscope.

Movie S1. Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote‐like forms in the intestine. Flagellated epimastigote‐like forms observed in an ex vivo intestine section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 27 seconds with one second intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 56 µm (x, y) x 10 µm (z).

Movie S2. Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote nest in the liver. Actively moving trypomastigotes observed in an ex vivo liver section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 90 minutes with one minute intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 149 µm x 163 µm.

Movie S3. Trypanosoma cruzi forms moving inside nest in the liver. Actively moving trypomastigotes observed in an ex vivo liver section of a CL‐DsRed infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 1 minute with one second intervals. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor). The nest dimensions are 50 µm x 22 µm.

Movie S4.Long‐time imaging of Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes nest in the liver. Three‐dimensional reconstruction of amastigote forms observed in an ex vivo liver section of a G‐GFP infected mouse at 8 dpi, acquired for 11 hours with thirty minutes intervals. The nest was imaged for 8 hours until fading began. The movie was edited with Imaris x64 software (Bitplane, Andor).

Supporting info item