Abstract

Currently, six glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1RAs) are approved for treating type 2 diabetes. These fall into two classes based on their receptor activation: short‐acting exenatide twice daily and lixisenatide once daily; and longer‐acting liraglutide once daily, exenatide once weekly, albiglutide once weekly and dulaglutide once weekly. The phase III trial of a seventh GLP‐1RA, taspoglutide once weekly, was stopped because of unacceptable adverse events (AEs). Nine phase III head‐to‐head trials and one large phase II study have compared the efficacy and safety of these seven GLP‐1RAs. All trials were associated with notable reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, although liraglutide led to greater decreases than exenatide formulations and albiglutide, and HbA1c reductions did not differ between liraglutide and dulaglutide. As the short‐acting GLP‐1RAs delay gastric emptying, they have greater effects on postprandial glucose levels than the longer‐acting agents, whereas the longer‐acting compounds reduced plasma glucose throughout the 24‐h period studied. Liraglutide was associated with weight reductions similar to those with exenatide twice daily but greater than those with exenatide once weekly, albiglutide and dulaglutide. The most frequently observed AEs with GLP‐1RAs were gastrointestinal disorders, particularly nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Nauseaoccurred less frequently, however, with exenatide once weekly and albiglutide than exenatide twice daily and liraglutide. Both exenatide formulations and albiglutide may be associated with higher incidences of injection‐site reactions than liraglutide and dulaglutide. GLP‐1RA use in clinical practice should be customized for individual patients, based on clinical profile and patient preference. Ongoing assessments of novel GLP‐1RAs and delivery methods may further expand future treatment options.

Keywords: albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, GLP‐1 receptor agonist, liraglutide, lixisenatide, taspoglutide, type 2 diabetes

Introduction

The early and intensive treatment of people with type 2 diabetes (T2D) is of key importance for reducing the risk of late diabetic complications, such as microvascular disease 1. T2D is linked to obesity 2, and the cornerstone of treatment is lifestyle changes to promote weight loss and increase exercise 3; however, because of the progressive nature of T2D, pharmacological therapy to address hyperglycaemia becomes necessary in almost all patients. Pharmacological treatment is, unfortunately, often associated with side effects such as weight gain (e.g. sulphonylureas, insulin and thiazolidinediones) 4, 5, hypoglycaemia (e.g. sulphonylureas and insulin) 6, 7, gastrointestinal (GI) discomfort [e.g. metformin and glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1RAs)] and genital infections [sodium‐glucose co‐transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors] 8, 9, 10. Notwithstanding the GI discomfort with GLP‐1RAs, their introduction over the last decade has greatly improved treatment of T2D 11, 12, 13, 14.

Human GLP‐1 is a member of the incretin family of glucoregulatory hormones, and is secreted in response to food ingestion 15, 16. Glucagon‐like peptide‐1 has multiple effects that are desirable in the treatment of T2D, including: glucose‐dependent increased insulin secretion; glucose‐dependent decreased glucagon secretion; delayed gastric emptying; increased satiety; and, as shown in some animal studies, protection of β‐cell mass 17, 18.

Unfortunately, although intravenously infused GLP‐1 can normalize plasma glucose concentrations in people with T2D 19, 20, it has an extremely short half‐life (1–2 min) 16 that limits its therapeutic value 21. Multiple GLP‐1RAs have been developed to recapitulate the physiological effects of GLP‐1 but with an extended duration of action (achieved by various changes to the molecular structure) compared with the native peptide 22. The present review examines the available evidence from published head‐to‐head clinical trials with GLP‐1RAs, and contrasts the relative clinical benefits of the short‐ and longer‐acting agents.

Characteristics of GLP‐1RAs

Seven GLP‐1RAs are included in the present review, all of which have been studied in phase III clinical trials. The GLP‐1RAs are: exenatide twice daily (Byetta®, AstraZeneca; approved in Europe in November 2006 and 28 May 2005 in USA 23, 24); liraglutide (Victoza®, Novo Nordisk; approved in Europe in June 2009 and 25 January 2010 in USA 25, 26); exenatide once weekly (Bydureon®, AstraZeneca; approved in Europe in June 2011 and 26 January 2012 in USA 27, 28); lixisenatide (Lyxumia®, Sanofi; approved in Europe in February in 2013 29 but not in the USA); albiglutide (Eperzan® and Tanzeum®, GlaxoSmithKline; approved in March 2014 in Europe and April 2014 in USA 30, 31); dulaglutide (Trulicity™, Lilly; approved in Europe in November 2014 and September 2014 in USA 32, 33); and taspoglutide (Ipsen/Roche). These have all now been approved for use in T2D, with the exception of taspoglutide, the development of which was halted because of serious hypersensitivity reactions and GI adverse events (AEs) during clinical trials; however, the available data for this compound are included in the present review to give a full picture of the GLP‐1RA family.

As a drug class, the GLP‐1RAs have proven efficacy for lowering glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) and decreasing weight in T2D, with a reduced risk of hypoglycaemia compared with insulin or sulphonylureas 34. These characteristics underlie the inclusion of GLP‐1RAs in various clinical practice guidelines. Their use as dual therapy with metformin after first‐line metformin and as triple therapy (in combination with metformin and a sulphonylurea/thiazolidinedione/insulin) is part of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes/American Diabetes Association recommendations 34. GLP‐1RAs are recommended as monotherapy, dual therapy and triple therapy by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology guidelines 35. Nonetheless, they differ substantially in their molecular structure and degree of homology to endogenous GLP‐1, both in their chemical and physiological properties and in their durations of action (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparative characteristics of the glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists

| Exenatide twice daily | Exenatide once weekly | Liraglutide once daily | Lixisenatide once daily | Albiglutide once weekly | Dulaglutide once weekly | Taspoglutide once weekly | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage amino acid sequence similarity to native GLP‐1 | 53% 36 | 53% 36 | 97% 37 | ≈50%* | 95% 38 | 90% 39 | 93% 40 |

| Properties of the drug | Resistant to DPP‐4 cleavage, largely due to the substitution of alanine in position 2 by glycine 41 | Encapsulated in biodegradable polymer microspheres 42 | C‐16 fatty acid confers albumin binding and heptamer formation 38 | Based on exenatide, but is modified by the deletion of one proline residue and addition of six lysine residues at the C‐terminal 43 | GLP‐1 dimer fused to albumin 44 | The GLP‐1 portion of the molecule is fused to an IgG4 molecule, limiting renal clearance and prolonging activity 39 | Modifications designed to hinder cleavage by DPP‐4 and by serine proteases and also allows greater receptor binding 45 |

| Half‐life | 2.4 h 46 | Half‐life is an unpublished result but steady state concentrations at 6–7 weeks 47 | 11–15 h 48 | 2.7–4.3 h 49 | 6–8 days 50 | ≈5 days 39 | 165 h 51 |

| Tmax | 2.1 h 46 | 2.1–5.1 h during the first 48 h 47 | ≈9–12 h 48 | 1.25–2.25 h 49 | 72–96 h 50 | 24–72 h 39 | 4, 6 and 8 h at 1, 8 and 30 mg doses, respectively 51 |

| Clearance | 9.1 l/h 52 | Unpublished results | 1.2 l/h 52 | 21.2–28.5 l/h 49 | 67 ml/h 53 | 0.75 mg and 1.5 mg at steady state was 0.073 and 0.107 l/h, respectively 29 | Unpublished results |

| Antibody formation |

• In head‐to‐head studies, antibodies were more common and titres were higher with exenatide once weekly compared with exenatide twice daily 54, 55, 56. • Antibodies did not correlate with rates of reported AEs 54, 55, 56. |

From six phase 3 studies, 8.7 and 8.3% of participants had low‐titre antibodies to liraglutide 1.2 and 1.8 mg, respectively, after 26 weeks 57 | Antibodies developed in: • 56–60% of participants treated with 20 µg once daily 58 • 43% of participants treated with 10 µg once daily and 71% treated with 20 µg twice daily 59 |

Antibodies developed in 3.7% of participants treated with albiglutide 14 | Dulaglutide antidrug antibodies in 1% of participants and dulaglutide neutralising antidrug antibodies in 1% of patients 13 | Detected in 49% of participants 40 | |

AE, adverse event; DPP‐4, dipeptidyl peptidase‐4; GLP‐1, glucagon‐like peptide‐1; GLP‐1RA, GLP‐1 receptor agonist; IgG4, immunoglobulin 4; Tmax, time to maximum plasma concentration.

Value based on similarity to exenatide.

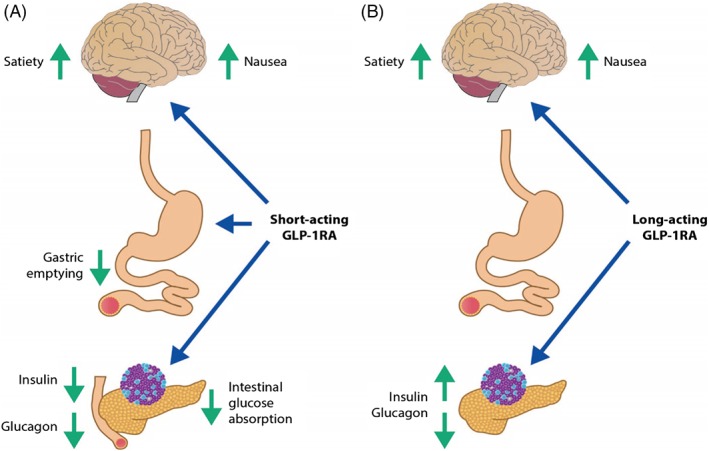

Several GLP‐1RAs (exenatide twice daily, exenatide once weekly and lixisenatide) are based on the exendin‐4 molecule, a peptide with 53% identity to native GLP‐1 36, 42, 43, while others, such as liraglutide, albiglutide, dulaglutide and taspoglutide are classified as GLP‐1RA analogues with 97, 95, 90 and 93% identity, respectively, to native GLP‐1 38, 39, 40. The GLP‐1RAs are, in addition, commonly considered to fall into two different classes based on their duration of receptor activation. The short‐acting compounds, delivering short‐lived receptor activation, comprise exenatide twice daily and lixisenatide once daily. The long‐acting compounds, which activate the GLP‐1 receptor continuously at their recommended dose, comprise liraglutide once daily, and the once‐weekly formulations of exenatide, albiglutide, dulaglutide and taspoglutide (Table 1). These different durations of action largely explain variations among GLP‐1RAs in their impact on fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 24‐h glucose profile and postprandial plasma glucose (PPG) levels 60, 61. Delayed gastric emptying, for example, is more strongly associated with short‐acting than longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs (Figure 1), and this may underlie the greater effects on PPG observed with short‐acting GLP‐1RAs. Meanwhile, the greater half‐lives of the longer‐acting compounds allow enhanced effects on the whole 24‐h glucose level, including FPG. Longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs do not significantly affect gastric motility. Instead, they exert more of their effect via the pancreas, increasing insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon secretion via paracrine release of somatostatin (Figure 1) 22.

Figure 1.

Gastric‐emptying effects of short‐acting versus longer‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists (GLP‐1RAs). (A) Short‐acting GLP‐1RAs suppress gastric emptying, which prolongs the presence of food in the stomach and upper small intestine; the reduced transpyloric flow causes delayed intestinal glucose absorption and diminished postprandial insulin secretion. Short‐acting GLP‐1RAs may also directly suppress glucagon secretion. (B) Longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs do not significantly affect gastric motility, because of tachyphylaxis. Instead, longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs exert more of their effect via the pancreas, increasing insulin secretion, and inhibiting glucagon secretion via paracrine release of somatostatin. By targeting the central nervous system, both shorter‐ (A) and longer (B) ‐acting GLP‐1RAs increase satiety and also may induce nausea. Adapted from Meier 22. Adapted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2012;8(12):728–42, copyright 2012.

Not only do GLP‐1RAs differ from each other in terms of their duration of action 39, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, they also show varying levels of affinity for the GLP‐1 receptor 62. This difference between GLP‐1RAs is also evident in their varying efficacy with regard to HbA1c reduction and weight loss, and differing tolerability profiles and potential for immunogenicity 22, 63, 64, 65. It is important to understand these specific characteristics to appropriately tailor the choice of GLP‐1RA to the individual patient. Head‐to‐head clinical trials are the best way to elucidate variations in efficacy and tolerability, and a number of such studies have been conducted with GLP‐1RAs in T2D.

Head‐to‐head Comparison Trials

To date, the results from nine phase III randomized trials that directly compare different pairs of GLP‐1RAs have been published 12, 13, 14, 40, 54, 55, 56, 66, 67. An overview of the designs of these studies is provided in Table 2. One large phase II study, comparing liraglutide and lixisenatide pharmacodynamics, is also included 61.

Table 2.

Design of published phase III (and one key phase II) randomized head‐to‐head studies of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes

| Study name | Treatment arms | Duration | Inclusion criteria | Primary endpoint | Key secondary endpoints |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DURATION‐1 54 | Exenatide once weekly vs exenatide twice daily vs | 30 weeks* | ≥16 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [≤7.0% (53 mmol/mol), ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) and ≤6.0% (42 mmol/mol)] |

| Therapy with diet and exercise, or with 1–2 OADs (metformin, SU and/or TZD) | |||||

| Changes in FPG, PPG, weight, BP, lipids and glucagon | |||||

| HbA1c 7.1–11.0% | |||||

| FPG <16 mmol/l | |||||

| Exenatide pharmacokinetics and paracetamol absorption | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| BMI 25–45 kg/m2 | |||||

| DURATION‐5 55 | Exenatide once weekly vs exenatide twice daily | 24 weeks | ≥18 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [<7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] |

| Treated with diet and exercise, or with metformin, SU, TZD or a combination | |||||

| Patients achieving FPG target (≤7.0 mmol/l) | |||||

| HbA1c 7.1–11.0% | |||||

| Changes in FPG, weight, BP and lipids | |||||

| FPG <15.5 mmol/l | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| BMI 25–45 kg/m2 | |||||

| Ji et al. 56 | Exenatide once weekly vs exenatide twice daily | 26 weeks | ≥20 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [≤7.0% (53 mmol/mol), ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol) and ≤6.0% (42 mmol/mol)] |

| Treated with 1–3 OADs (metformin, SU, TZD) | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–11.0% | |||||

| Changes in FSG, SMPG, weight, lipids, HOMA‐β and insulin sensitivity | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| BMI 21–35 kg/m2 | |||||

| DURATION‐6 67 | Exenatide once weekly vs liraglutide once daily | 26 weeks | ≥18 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c target (<7.0%) |

| Treated with diet and exercise and OADs (metformin, SU, metformin + SU, or metformin + pioglitazone) | |||||

| Changes in FSG, weight, BP and lipids | |||||

| Patient‐reported outcomes | |||||

| HbA1c 7.1–11.0% | |||||

| BMI ≤45 kg/m2 | |||||

| Stable body weight | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| LEAD‐6 66 | Exenatide twice daily vs liraglutide once daily | 26 weeks* | 18–80 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants reaching HbA1c targets [<7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] |

| Therapy with metformin, SU or both | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–11.0% | Changes in FPG, SMPG, weight, BP, lipids, glucagon and HOMA‐β | ||||

| BMI ≤45 kg/m2 | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| GetGoal‐X 12 | Exenatide twice daily vs lixisenatide once daily | 24 weeks | 21–84 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [<7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] |

| Treated with metformin | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–10.0% | |||||

| Changes in FPG and weight | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| HARMONY 7 14 | Albiglutide once weekly vs liraglutide once daily | 32 weeks | ≥18 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [<7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and <6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] |

| Treated with metformin, SU, TZD or a combination | |||||

| Changes in FPG and weight | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–10.0% | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| BMI 20–45 kg/m2 | |||||

| AWARD‐6 13 | Dulaglutide once weekly vs liraglutide once daily | 26 weeks | ≥18 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Participants achieving HbA1c targets [<7.0% (53 mmol/mol) and ≤6.5% (48 mmol/mol)] |

| Treated with metformin | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–10.0% | |||||

| Change in FSG, SMPG, weight, BMI and HOMA‐β | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| T‐emerge 2 40 | Exenatide twice daily vs taspoglutide once weekly | 24 weeks* | 18–75 years of age | Change in HbA1c | Changes in FPG and weight (assessed over 52 weeks) |

| Treated with metformin and/or TZD | |||||

| Changes in fasting pro‐insulin, fasting pro‐insulin/insulin ratio and HOMA‐β (assessed over 52 weeks) | |||||

| HbA1c 7.0–10.0% | |||||

| BMI 25–45 kg/m2 | |||||

| Stable body weight | |||||

| Safety and tolerability | |||||

| Kapitza et al.† 61 | Lixisenatide once daily vs liraglutide once daily | 28 days | 37–74 years of age | Change in PPG exposure | Changes in maximum PPG excursion after a standardized breakfast test meal |

| Treated with metformin | |||||

| HbA1c 6.5–9.0% | |||||

| Changes in premeal serum insulin, serum C‐peptide and plasma glucagon levels | |||||

| 24‐h plasma glucose profile | |||||

| Mean HbA1c | |||||

| Safety and tolerability |

All studies were open‐label.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FSG, fasting serum glucose; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin HOMA‐β, homeostasis model assessment of β‐cell function; OAD, oral antidiabetic drug; PPG, postprandial glucose; SMPG, self‐measured plasma glucose; SU, sulphonylurea; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TZD, thiazolidinedione.

Also included an extension phase up to 52 weeks.

Phase II study (n = 148).

Of the GLP1‐RAs in the head‐to‐head trials, exenatide twice daily and liraglutide were the most common comparators (Table 2). The majority of the phase III studies included in the present review were of ∼6 months' duration, although several also had extension phases to give trial durations up to 12 months (Table 2). All of the phase III trials examined changes in HbA1c as the primary endpoint; the phase II study by Kapitza et al. 61, however, used changes in PPG exposure as the primary endpoint.

In general, baseline characteristics were similar across trial populations and between treatment groups within individual trials (Table 3). The mean age of participants ranged from 55 to 61 years across the studies, with mean duration of diabetes ranging from 6 to 9 years. Mean baseline HbA1c levels were in the range of 8.0 (64 mmol/mol) to 8.7% (72 mmol/mol) across the studies, except for the phase II study (in which HbA1c levels were lower) 61. Glucose concentrations in the range of 9.1–9.9 mmol/l were determined in plasma and serum samples, and mean baseline weight was consistently in the range 91–102 kg, except in an Asian study, in which mean weight was lower 56 (Table 3). Differences in key study outcomes are discussed in the following sections.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of participant populations in published phase III (and one phase II) randomized head‐to‐head studies of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes

| DURATION‐1 (30 weeks) 54 | DURATION‐5 (24 weeks) 55 | Ji et al. (26 weeks) 56 | DURATION‐6 (26 weeks) 67 | LEAD‐6 (26 weeks) 66 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exenatide 2 mg once weekly (n = 148) | Exenatide10 µg twice daily (n = 147) | Exenatide 2 mg once weekly (n = 129) | Exenatide 10 µg twice daily (n = 123) | Exenatide 2 mg once weekly (n = 340) | Exenatide 10 µg twice daily (n = 338) | Exenatide 2 mg once weekly (n = 461) | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily (n = 450) | Exenatide 10 µg twice daily (n = 231) | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily (n = 233) | |

| Age, years | 55 (10) | 55 (10) | 56 (11) | 55 (10) | 55 (11) | 56 (10) | 57 (9) | 57 (10) | 57 (11) | 56 (10) |

| Male/female, % | 55/45 | 51/49 | 60/40 | 55/45 | 54/46 | 54/46 | 55/45 | 54/46 | 55/45 | 49/51 |

| Race, % | ||||||||||

| White | 83 | 73 | 63 | 55 | — | — | 83 | 82 | 91 | 93 |

| Black/African American | 6 | 13 | 5 | 7 | — | — | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 100 | 100 | 12 | 13 | 2 | <1 |

| Other* | 11 | 14 | 29 | 33 | — | — | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Multiple† | — | — | — | — | — | — | <1 | 1 | — | — |

| Ethnic origin | ||||||||||

| Hispanic or Latin American, % | 11 | 14 | 29 | 33 | — | — | 21 | 22 | 11 | 14 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 35 (5) | 35 (5) | 34 (6) | 33 (5) | 26 (4) | 27 (3) | 32 (6) | 32 (5) | 33 (6) | 33 (6) |

| Weight, kg | 102 (19) | 102 (21) | 97 (21) | 94 (19) | 70 (12) | 70 (12) | 91 (20) | 91 (19) | 93 (20) | 93 (20) |

| HbA1c, % | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.3 (1.0) | 8.5 (1.1) | 8.4 (1.2) | 8.7 (1.0) | 8.7 (1.0) | 8.5 (1.0) | 8.4 (1.0) | 8.1 (1.0) | 8.2 (1.0) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 67 (11) | 67 (11) | 69 (12) | 68 (13) | 72 (11) | 72 (11) | 69 (11) | 68 (11) | 65 (11) | 66 (11) |

| FSG/FPG, mmol/l | 9.6 (2.4) | 9.2 (2.3) | 9.6 (2.6) | 9.3 (2.6) | 9.1 (2.4) | 9.4 (2.7) | 9.6 (2.5) | 9.8 (2.6) | 9.5 (2.4) | 9.8 (2.5) |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 7 (6) | 6 (5) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 8 (5) | 9 (6) | 8 (6) | 9 (6) | 8 (6) | 9 (6) |

| SBP, mmHg | 128 (1)‡ | 130 (1)‡ | 130 (1)‡ | 128 (1)‡ | 131 (1)‡ | 132 (1)‡ | 132 (14) | 134 (14) | 134 (17) | 132 (16) |

| DBP, mmHg | 78 (1)‡ | 80 (1)‡ | 78 (1)‡ | 77 (1)‡ | 79 (1)‡ | 80 (1)‡ | 79 (9) | 80 (9) | 79 (9) | 80 (8) |

| GetGoal‐X (24 weeks) 12 | HARMONY 7 (32 weeks) 14 | AWARD‐6 (26 weeks) 13 | T‐emerge 2 (24 weeks) 40 | Kapitza et al. (28 days)§ 61 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exenatide 10 µg twice daily (n = 316) | Lixisenatide 20 µg once daily (n = 318) | Albiglutide 50 mg once weekly (n = 404) | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily (n = 408) | Dulaglutide 1.5 mg once weekly (n = 299) | Liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily (n = 300) | Exenatide 10 µg twice daily (n = 373) | Taspoglutide 10 mg once weekly (n = 384) | Taspoglutide 20 mg once weekly (n = 392) | Lixisenatide 10–20 µg once daily (n = 77) | Liraglutide 0.6–1.8 mg once daily (n = 71) | |

| Age, years | 58 (11) | 57 (9) | 55 (10) | 56 (10) | 57 (9) | 57 (10) | 55 (10) | 56 (10) | 56 (10) | 61 (8) | 60 (9) |

| Male/female, % | 59/41 | 48/53 | 47/53 | 53/47 | 46/54 | 50/50 | 49/51 | 58/42 | 52/48 | 64/36 | 70/30 |

| Race, % | |||||||||||

| White | 92 | 93 | N/A | N/A | 86 | 86 | 85 | 85 | 85 | 99 | 100 |

| Black/African American | 3 | 3 | N/A | N/A | 7 | 5 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 | — |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | <1 | — | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | — |

| Other* | 3 | 4 | N/A | N/A | 7 | 8 | 15 | 15 | 15 | — | — |

| Multiple† | — | — | N/A | N/A | <1 | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | — | — |

| Ethnic origin | |||||||||||

| Hispanic/Latin American, % | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 25 | 24 | 20 | 18 | 21 | N/A | N/A |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 34 (7) | 34 (6) | 33 (6) | 33 (6) | 34 (5) | 34 (5) | 34 (5) | 34 (5) | 33 (5) | 31 (4) | 31 (4) |

| Weight, kg | 96 (23) | 94 (20) | 92 (21) | 93 (22) | 94 (18) | 94 (19) | 95 (19) | 96 (20) | 93 (19) | 91 (15) | 93 (17) |

| HbA1c, % | 8.0 (0.8) | 8.0 (0.8) | 8.2 (0.9) | 8.2 (0.8) | 8.1 (0.8) | 8.1 (0.8) | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.1 (0.9) | 8.1 (0.9) | 7.2 (0.6) | 7.4 (0.8) |

| HbA1c, mmol/mol | 64 (9) | 64 (9) | 66 (10) | 66 (9) | 65 (9) | 65 (9) | 65 (10) | 65 (10) | 65 (10) | 55 (7) | 57 (9) |

| FPG/FSG, mmol/l | 9.7 (2.3) | 9.7 (2.0) | N/A | N/A | 9.3 (2.2) | 9.2 (2.3) | 9.9 (2.7) | 9.9 (2.6) | 9.8 (2.4) | N/A | N/A |

| Duration of diabetes, years | 7 (5) | 7 (6) | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 7 (5) | 6 (5) | 7 (6) | 7 (N/A) | 7 (N/A) |

| SBP, mmHg | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 132 (15) | 131 (15) | 131 (1)‡ | 132 (1)‡ | 132 (1)‡ | N/A | N/A |

| DBP, mmHg | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 80 (10) | 79 (9) | 79 (0)‡ | 80 (0)‡ | 80 (0)‡ | N/A | N/A |

BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FSG, fasting serum glucose; GLP‐1RA, glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; N/A, not available; SBP, systolic blood pressure; T2D, type 2 diabetes.

All data are rounded to the nearest integer, except for HbA1c and FPG/FSG, which are presented to the nearest decimal point. Data are mean (standard deviation) unless stated otherwise.

Other non‐white.

As defined by study.

Standard error used.

Phase II study.

Glycaemic Measurements

In all of the head‐to‐head trials, the GLP‐1RAs studied led to notable reductions in HbA1c.

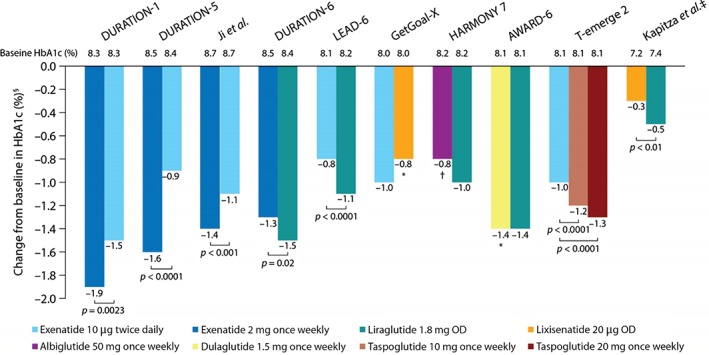

These reductions ranged between 0.3 (3 mmol/mol) and 1.9% (21 mmol/mol). Although data are not comparable across studies because of differences in study design and patient cohorts, there were some important differences between treatment arms in the magnitude of HbA1c reductions (Figure 2). In particular, in the DURATION‐1, DURATION‐5 studies and the study by Ji et al. 54, 55, 56, exenatide once weekly produced both more consistent and greater reductions in HbA1c levels than did exenatide twice daily (p ≤ 0.0023). In the GetGoal‐X study 12, meanwhile, exenatide twice daily showed a numerically greater HbA1c reduction than lixisenatide. Liraglutide, in the DURATION‐6 and LEAD‐6 studies, led to greater HbA1c reductions than both exenatide twice daily and once weekly (p ≤ 0.02) 66, 67. Liraglutide also led to greater reductions in HbA1c than lixisenatide (p < 0.01) in the phase II study (although it was not the primary endpoint and the study duration was short 61). Likewise, in the HARMONY 7 study 14, liraglutide led to greater reductions in HbA1c than albiglutide (however, the predefined non‐inferiority criteria for albiglutide were not met). In the AWARD‐6 study 13, the reduction in HbA1c did not differ between liraglutide and dulaglutide after 26 weeks of treatment. In the T‐emerge 2 study, taspoglutide at 10 and 20 mg led to greater reductions in HbA1c than exenatide 10 µg twice daily (p < 0.0001) 40.

Figure 2.

Reductions in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in published phase III (and one phase II) randomized head‐to‐head studies of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. *Non‐inferiority criteria met. †Non‐inferiority criteria not met. ‡Phase II study. §A 1% change in HbA1c corresponds to a 10.93 mmol/mol change in The International Federation of Clinical Chemistry units.

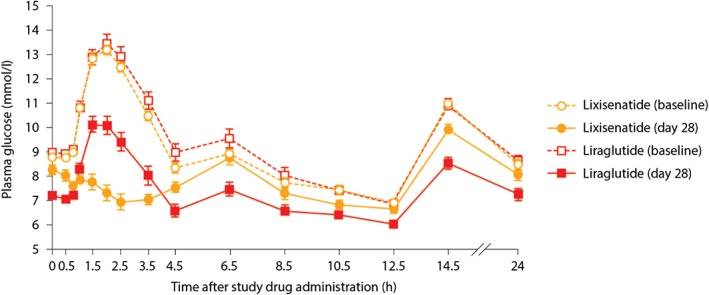

In addition, PPG and FPG were assessed in many of these trials. As expected, based on the delayed gastric emptying seen with the short‐acting GLP‐1RAs, exenatide twice daily and lixisenatide had greater effects on PPG than the longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs and this improvement was observed after the meal that followed the injection. For example, in the phase II study, lixisenatide administered before breakfast was associated with significantly greater reductions in maximum PPG excursion than liraglutide (−3.9 mmol/l vs −1.4 mmol/l, respectively; p < 0.0001), resulting in PPG of 7.3 and 10.1 mmol/l, respectively, 2 h after starting breakfast 61. The differential effect on PPG is evident in the 24‐h plasma glucose profiles shown in Figure 3. These data are supported by results from another phase II study, which showed that lixisenatide had a significantly greater effect than liraglutide in reducing area under the PPG curve after a standardized solid breakfast. This difference was thought to be attributable to significant delays in gastric emptying with lixisenatide versus liraglutide, which reduced post‐breakfast blood glucose exposure 68.

Figure 3.

Mean 24‐h postprandial plasma glucose profiles at baseline and day 28. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Adapted from Kapitza et al. 61.

Similarly, in a comparison of exenatide twice daily and exenatide once weekly, the mean change from baseline in 2‐h PPG was significantly greater with the twice‐daily versus the once‐weekly formulation (−6.9 mmol/l vs −5.3 mmol/l, respectively; p = 0.0124), and the delay in gastric emptying was more pronounced with exenatide twice daily than with exenatide once weekly 54. Furthermore, in a study conducted in Asian participants by Ji et al. 56, exenatide twice daily produced significantly greater reductions in postprandial blood glucose than exenatide once weekly based on assessments 2 h after each of the morning and evening meals (p < 0.001); however, in a sub‐analysis of participants in the T‐emerge 2 study, the longer‐acting GLP‐1RA taspoglutide had similar effects to exenatide twice daily on postprandial metabolism, although the mechanisms underlying this effect are not entirely clear 69.

Generally, the longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs improve glucose control via a downward shift of the whole 24‐h glucose curve, which explains the greater overall efficacy compared with the short‐acting exenatide twice daily and lixisenatide once daily. While the short‐acting GLP‐1RAs typically have an advantage with respect to PPG, the situation is reversed with FPG. Here, the longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs resulted in greater improvements. For example, in DURATION‐1, changes in FPG were significantly greater after 30 weeks with exenatide once weekly than with exenatide twice daily (−2.3 mmol/l vs −1.4 mmol/l, respectively; p < 0.0001) 54. Similarly, in DURATION‐5, the mean change in FPG at 24 weeks was significantly greater with exenatide once weekly than with exenatide twice daily (−1.9 mmol/l vs −0.7 mmol/l, respectively; p = 0.0008) 55. The longer‐acting GLP‐1RA taspoglutide was also associated with a significantly greater reduction in FPG than short‐acting exenatide twice daily at 24 weeks 40. Accordingly, in the phase II study, changes in FPG were greater with liraglutide than with lixisenatide (−1.3 mmol/l vs −0.3 mmol/l, respectively; p < 0.0001) 61. Likewise, the long‐acting liraglutide once daily demonstrated greater improvements than exenatide twice daily (−1.6 mmol/l vs −0.6 mmol/l, respectively) 66. Comparisons of once‐daily liraglutide with once‐weekly formulations produced a mixed pattern: liraglutide demonstrated superiority to exenatide once weekly (−2.1 mmol/l vs −1.8 mmol/l, respectively; p = 0.02) 67 and albiglutide once weekly (−1.7 mmol/l vs −1.2 mmol/l, respectively; p = 0.0048) 14 in lowering fasting serum glucose and FPG, respectively, but no significant difference compared with dulaglutide once weekly (1.90 mmol/l vs 1.93 mmol/l, respectively) 13.

Effects on Weight

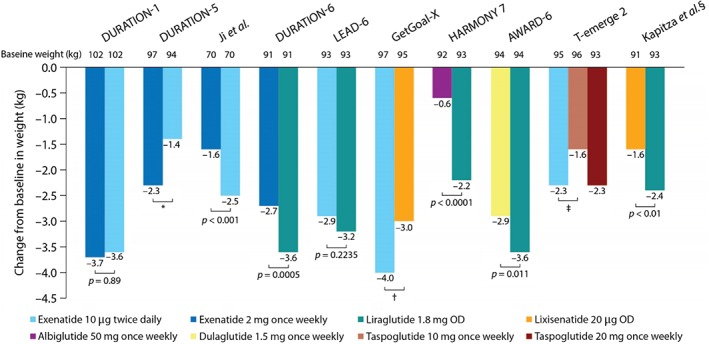

As a class, the GLP‐1RAs have all been shown to have a weight‐reduction effect (Figure 4), and this effect is significantly greater than is typically seen with most other therapeutic classes 70. Indeed, a systematic review of clinical trials involving exenatide twice daily, liraglutide and exenatide once weekly in participants with a body mass index (BMI) ≥25 kg/m2 (with or without T2D) found a greater reduction in weight with these compounds versus non‐GLP‐1RA‐treated control compounds (weighted mean difference: −2.9 kg) 70.

Figure 4.

Reductions in weight in published phase III (and one phase II) randomized head‐to‐head studies of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists in type 2 diabetes. *Difference was not significant at week 24, although it was significant at week 20. †Not stated if difference was significant. ‡Data shown at week 24; however, at week 52, weight loss was significantly lower in the taspoglutide 10 mg versus exenatide group (p = 0.01). §Phase II study.

The weight benefit varies among GLP‐1RAs and studies. For example, Ji et al. 56 found that exenatide twice daily was associated with a significantly greater reduction in weight than exenatide once weekly (p < 0.001) but, in DURATION‐1 and DURATION‐5 54, 55, weight loss was not significantly different between the two exenatide formulations. In the T‐emerge 2 study, exenatide twice daily showed a greater (non‐significant) reduction in weight than taspoglutide 10 mg once weekly but showed no difference in weight loss compared with taspoglutide 20 mg once weekly 40. In the LEAD‐6 study, exenatide twice daily and liraglutide treatment led to similar levels of weight loss (3.2 and 2.9 kg, respectively; p = 0.2235) 66. Exenatide twice daily was associated with greater (non‐significant) weight loss than lixisenatide in the GetGoal‐X study 12, and liraglutide treatment led to greater weight loss than lixisenatide in the study by Kapitza et al. 61 (p < 0.01; Figure 3). Other head‐to‐head trials revealed significantly greater reductions in weight with liraglutide than the once‐weekly treatments exenatide (p = 0.0005), albiglutide (p < 0.0001) and dulaglutide (p = 0.011; Figure 4) 13, 14, 67. Between‐treatment differences were 0.9, 1.6 and 0.7 kg, respectively 13, 14, 67.

In the Ji et al. 56 and DURATION‐6 studies 67, the greatest weight loss was observed in participants treated with exenatide (once weekly or twice daily) or liraglutide with the highest baseline BMI. Furthermore, in a retrospective analysis of seven phase III trials from the liraglutide diabetes development programme, a slightly greater weight reduction was observed in participants treated with liraglutide, with a longer duration of GI AEs 71.

The exact mechanism by which GLP‐1 exerts its anorectic effects is a matter of contention, but both peripheral and brain GLP‐1 receptors seem to be involved 72, 73. It is also unclear whether the reduced weight loss with the large molecules, albiglutide and dulaglutide, compared with liraglutide can be explained by less direct activation of the GLP‐1 receptors in the hypothalamic areas and brain stem. Indeed, compared with liraglutide, the larger molecular sizes of albiglutide and dulaglutide may hinder transport across the blood–brain barrier or through fenestrated capillaries 73. Alternatively, it may be a question of suboptimum dosing of the once‐weekly GLP‐1RAs; this may also may explain the differences in reduction in HbA1c level.

Cardiovascular Measurements

Blood Pressure

Improvements in both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) have been reported in clinical trials of GLP‐1RAs. Indeed, a meta‐analysis of trials involving exenatide once weekly, exenatide twice daily or liraglutide found that these treatments significantly decreased SBP: by −1.79 and −2.39 mmHg compared with placebo and active controls, respectively 74. There was also a trend towards decreased DBP with GLP‐1RAs, but reductions did not reach statistical significance.

Head‐to‐head trials have not found significant differences in effects on blood pressure (BP) among different GLP‐1RAs 12, 13, 14, 54, 55, 56, 66, 67. For example, in the DURATION‐1 study 54, both SBP and DBP were reduced over 30 weeks of treatment with exenatide once weekly and exenatide twice daily (mean change in SBP −4.7 and −3.4 mmHg and in DBP: −1.7 and −1.7 mmHg, respectively). In the DURATION‐5 study, larger reductions in SBP (mean change: exenatide once weekly −7.9 mmHg and exenatide twice daily −7.7 mmHg) were observed in participants with elevated baseline SBP (≥130 mmHg) but this reduction was similar in the two treatment arms. In the LEAD‐6 trial 66, exenatide twice daily and liraglutide were associated with similar reductions in SBP and DBP at 26 weeks (mean change in SBP −2.0 and −2.5 mmHg; change in DBP −2.0 and −1.1 mmHg, respectively); however, in the extension phases of DURATION‐1 and LEAD‐6, which continued to 52 weeks, participants switching from exenatide twice daily to either exenatide once weekly or liraglutide experienced further reductions in SBP (−3.8 mmHg in both studies) 75, 76.

Reductions in SBP and DBP were also observed in the GetGoal‐X trial of lixisenatide vs exenatide twice daily (mean change in SBP: −2.5 and −2.9 mmHg; change in DBP: −1.8 and −1.3 mmHg, respectively) 12, and in the AWARD‐6 trial of dulaglutide vs liraglutide (mean change in SBP −3.4 and −2.8 mmHg; change in DBP −0.2 and −0.3 mmHg, respectively) 13. Again, there were no statistically significant differences between treatments in either study.

Heart Rate

Increases in resting heart rate have been reported with GLP‐1RAs 74. Although the underlying physiological mechanisms have not yet been defined, the activation of the GLP‐1 receptors in the sino‐atrial node could play a role 77.

A meta‐analysis of studies involving exenatide once weekly, exenatide twice daily or liraglutide found that these treatments increased heart rate by 1.86 beats/min (bpm) vs placebo and by 1.90 bpm vs active comparators 74. Head‐to‐head trials have suggested that heart rate increases may be smaller with exenatide twice daily than exenatide once weekly or liraglutide 55, 56, 66. Dulaglutide is also associated with a small increase in heart rate, of similar magnitude to that with liraglutide 13. Lixisenatide and albiglutide did not appear to be associated with clinically relevant increases in heart rate 12, 14. Since heart rate was mostly estimated during daytime, 24‐h monitoring was needed to understand the different effects of the short‐ and longer‐acting GLP‐1RAs on heart rate. In a phase II study by Meier et al. 68, liraglutide doses increased the mean ± standard error 24‐h heart rate from baseline by 9 ± 1 bpm versus 3 ± 1 bpm with lixisenatide (p < 0.001) at week 8. Greater heart rate increases at week 8 with liraglutide were observed at night time, while heart rate increases with lixisenatide were greatest during the day.

Potential explanations for the increased heart rate observed in these studies could include a reflex mechanism compensating for vasodilation and lowering of BP 77 . Indeed, in a pooled analysis of six clinical trials, liraglutide was associated with significantly greater SBP reductions than glimepiride and insulin glargine and rosiglitazone 78.

Safety and Tolerability

Gastrointestinal Adverse Events

The most frequently observed AEs with GLP‐1RAs are GI disorders, particularly nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea 11, 12, 13, 14. Nausea occurred less frequently with exenatide once weekly than exenatide twice daily or liraglutide 54, 55, 56, 67. Lixisenatide also showed reduced rates of nausea compared with exenatide twice daily 12. Among the two most recently approved GLP‐1RAs, albiglutide had lower rates of nausea than liraglutide 14, whereas dulaglutide had similar rates compared with liraglutide 13; however, by far the highest rates of nausea were observed with taspoglutide: 53 and 59% with 10 and 20 mg once weekly, respectively, compared with 35% among participants treated with exenatide twice daily 40. This was one of the key reasons why the clinical development of taspoglutide was halted.

Thyroid Safety and Calcitonin Levels

In rodent models, GLP‐1RAs have been linked to the release of calcitonin, and the potential formation of thyroid tumours 79, but there is no evidence of a causal relationship between GLP‐1RAs and thyroid tumours in humans. Across the phase III head‐to‐head studies described in the present review, mean calcitonin levels were largely unchanged, and only one case of treatment‐emergent thyroid cancer was observed (a papillary thyroid carcinoma in a patient treated with liraglutide in AWARD‐6) 13.

Pancreatitis

Concerns have been raised with respect to the potential pancreatic side effects associated with GLP‐1RAs 80, 81. The 10 head‐to‐head studies discussed in the present review (Table 2) did not have sufficient power to detect differences between GLP‐1RAs in the rates of these rare events. Indeed, in only one of these studies was there more than one case of pancreatitis: three cases were reported in the HARMONY‐7 trial (one in the albiglutide group and two in the liraglutide group), from among 812 participants who received the study drug. There are limited published data on the effects of GLP‐1RAs on pancreatic enzymes in the head‐to‐head studies, and it is not possible to compare lipase level among studies because different methods have been used in their evaluation; however, in an 8‐week study comparing lixisenatide 20 µg once daily with liraglutide 1.2 and 1.8 mg once daily, a greater mean increase in lipase was reported with liraglutide compared with exenatide, while amylase was within the normal range for both GLP‐1RAs 68.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have agreed that assertions concerning a causal association between incretin‐based drugs and pancreatitis or pancreatic cancer, as expressed recently in the scientific literature and in the media, are inconsistent with current data; however, the FDA and the EMA have not reached a final conclusion regarding such a causal relationship 81. Notably, the FDA requires evidence of cardiovascular safety of new glucose‐lowering agents in large clinical endpoint trials, and, as a by‐product of these trials, clinical events related to pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer will be assessed. The first results from the Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes After Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With AVE0010 (Lixisenatide; ELIXA; NCT01147250) study comparing lixisenatide and placebo were presented at the American Diabetes Association 2015 Scientific Sessions. The 2‐year follow‐up data showed that the effect of lixisenatide compared with placebo was neutral for the primary composite endpoint: cardiovascular death, non‐fatal myocardial infarction, non‐fatal stroke or hospitalization for unstable angina (13.4% vs 13.2%). Furthermore, there was no elevation in pancreatitis and pancreas cancer with lixisenatide. Likewise, no elevation in heart rate was observed, probably explained by the short duration of action of lixisenatide given before breakfast. Lixisenatide led to a small change in HbA1c of 0.27%, in weight of 0.7 kg and in SBP of 0.8 mmHg vs placebo 82.

Following on from that study, the first results of the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcome Results ‐ A Long Term Evaluation in 2015 (LEADER; NCT01179048); the Exenatide Study of Cardiovascular Event Lowering Trial (EXSCEL; NCT01144338) study, comparing exenatide once weekly and placebo; and the Researching Cardiovascular Events With a Weekly Incretin in Diabetes (REWIND; NCT01394952) study, comparing dulaglutide and placebo, are estimated to end in 2015, 2018 and 2019, respectively.

Injection‐site Reactions

It is difficult to compare injection‐site reactions among the studies because of differences in methods of reporting outcomes. Overall, once‐weekly GLP‐1RAs appear to be associated with higher incidences of injection‐site reaction than exenatide twice daily 40, 54, 55, 56 or liraglutide once daily 14, 67.

For example, in HARMONY‐7, injection‐site reactions occurred more frequently with albiglutide (13%) than with liraglutide (5%; p = 0.0002) 14. A similar observation was made in DURATION‐6 67, in which participants treated with exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide showed higher incidences of injection‐site nodules (10% vs 1%, respectively), injection‐site pruritus (3% vs <1%, respectively) and injection‐site erythema (2% vs <1%, respectively). The exception appears to be dulaglutide once weekly, in AWARD‐6, which was associated with low rates (<1%) of injection‐site reactions, similar to those observed with liraglutide 13. The higher rates of injection‐site reactions reported in these studies is consistent with results seen with other sustained‐release injectable drug formulations that undergo in vivo degradation 83, 84. In a similar pattern, in the GetGoal‐X study 12, lixisenatide once daily was associated with more injection‐site reactions than exenatide twice daily (8.5% vs 1.6%).

Immunogenicity

As GLP‐1RAs are peptides, antibody formation could potentially occur that results in injection‐site reactions, loss of efficacy and anaphylaxis. Evidence to date, from several head‐to‐head trials, indicates that antibodies are formed against GLP‐1RAs 13, 14, 40, 54, 55, 56, 57.

The development of antibodies against exenatide was reported in the drug's clinical trial programme 85. In head‐to‐head studies, anti‐exenatide antibodies were more common, and titres were higher, with exenatide once weekly than with exenatide twice daily 54, 55, 56; however, reductions in HbA1c were still significant in participants with or without antibodies, and the presence of antibodies did not correlate with reported rates of AEs 54, 55, 56.

Antibody formation has also been reported in liraglutide clinical trials, although a meta‐analysis of the LEAD studies found lower immunogenicity with liraglutide than with exenatide twice daily and no effect of liraglutide immunogenicity on glycaemic efficacy 57.

In the GetGoal‐Mono study 58, the development of antibodies was reported in 56–60% of participants (undergoing different treatment regimens) treated with 20 µg lixisenatide once daily as a final dose. In another monotherapy study by Ratner et al. 59, antibodies were found in 43 and 71% of participants treated with 10 µg lixisenatide once daily and 20 µg twice daily, respectively. No notable differences were reported in terms of safety and efficacy between antibody‐positive and ‐negative participants 58, 59.

Antibody formation occurred relatively rarely in phase III trials of dulaglutide and albiglutide 13, 14, but no comparison could be made with liraglutide in these studies, as anti‐liraglutide antibodies were not assessed.

Finally, in the T‐emerge 2 study, anti‐taspoglutide antibodies were detected in 49% of participants 40. In this trial, levels of systemic allergic reactions were also considered to be unacceptably high (6% of participants in each of the taspoglutide groups).

The immunogenicity reported in the trials of exenatide, lixisenatide and liraglutide would appear to have little impact on the efficacy and safety of these GLP‐1RAs.

Patient Preferences and Drug Administration

Patient Preference

Participant‐preference data are limited within the major head‐to‐head trials of GLP‐1RAs; however, in DURATION‐1 86, participant‐assessed treatment satisfaction and quality of life improved significantly between weeks 30 and 52 among those switching from exenatide twice daily to exenatide once weekly. Meanwhile, in DURATION‐6 67, participant satisfaction and mental health were improved with both liraglutide and exenatide once weekly (p < 0.0001), with no significant differences between groups.

Survey data on patient preferences for exenatide twice daily versus liraglutide have also been collected 87. Using a time trade‐off method, 96% of respondents preferred the product profile representing liraglutide over that representing exenatide. The analysis showed that efficacy (lowering of HbA1c) is the most important attribute influencing patient preference, followed by nausea, hypoglycaemia and dosing schedule 87.

The general attitude of patients to once‐weekly GLP‐1RA formulations has also been assessed 88. In an online survey of adults with T2D, current injection users were more likely (p < 0.001) than non‐injection users to perceive potential benefits of once‐weekly treatment, such as greater convenience, better medication adherence and improved quality of life 88. A total of 47% of respondents said that they would take an injectable once‐weekly medication if it was recommended by their physician; current injection users were more likely than non‐injection users to respond in this way (73% vs 32%, respectively; p < 0.001). Concerns about once‐weekly medications in this population are related to consistency of dose over time, potential forgetfulness and cost.

Drug Administration

To date, while there have been studies comparing various prefilled insulin injection pens, there are very few data available regarding the different injection devices for the GLP‐1RAs. One aspect that has been investigated is the use of narrower versus wider needles for injection devices. Both exenatide twice daily and exenatide once weekly are administered using a 23‐gauge needle while liraglutide is injected using a narrower 32‐gauge needle, which has been suggested to decrease injection discomfort. In one study comparing insulin injection using two different NovoFine® needles, 58% preferred the NovoFine 32‐gauge tip, 26% preferred the NovoFine 30‐gauge tip, while 16% had no preference (p < 0.001 between needles) 89. Although this study did not examine the use of GLP‐1RAs, the results are nonetheless applicable to other injection devices, and suggest a strong patient preference for narrower needles.

Future Possibilities for GLP‐1 RA Treatment

The use of GLP‐1RAs is now well established in both the early and late stages of T2D. Further research is ongoing 90, and is presently focused on several key areas.

Further development and testing of once weekly GLP‐1RAs. Both albiglutide and dulaglutide are once‐weekly formulations that were approved in Europe and the USA in 2014; hence, additional work will be required to better understand their clinical profiles in normal clinical practice. Meanwhile, new GLP‐1RAs intended for once‐weekly dosing, such as semaglutide, are in phase III trials.

Oral and inhaled formulations. All of the currently available GLP‐1RAs are administered by injection, but a desire to avoid needles, as noted with insulin administration, can be a barrier to starting injectable therapy in some people with T2D 91. Alternative routes of administration, in particular oral and inhaled formulations, could therefore improve the acceptability of these therapies for some patients. Work is ongoing, but the key challenge will be to ensure adequate absorption and prolongation of action of inhaled GLP‐1RAs.

Osmotic pump system. The ITCA 650 is another alternative route to administration, a miniature osmotic pump system that is designed to deliver zero‐order, continuous subcutaneous release of exenatide for up to 12 months with a single placement. A recent study showed that treatment for up to 24 weeks with the ITCA 650 resulted in significant improvements in HbA1c, FPG and body weight in patients with T2D inadequately controlled on metformin monotherapy 92.

Combination of GLP‐1RAs with basal insulin therapy. In addition to additive glycaemic benefits, the weight loss and low hypoglycaemia risk associated with GLP‐1RAs could at least partially offset the weight gains and risk of hypoglycaemia associated with insulin use 93. Recent trials have shown the efficacy of combining insulin and GLP‐1RAs in T2D 94, 95. Meanwhile, a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide has been developed as a once‐daily injection, and resulted in improved glycaemic control compared with its components given alone in a phase III trial 96.

Potential use of GLP‐1RAs in T1D. There is evidence to suggest that people with T1D can achieve weight loss and improved glycaemic control on less insulin without an increase in hypoglycaemia when a GLP‐1RA is added to insulin therapy 97, 98. Further studies are ongoing.

Many other peptide hormones stimulate insulin secretion and regulate appetite by inducing satiety. Peptide YY (PYY) is produced in the intestinal L‐cells and reduces appetite. Dual co‐agonists developed in a single molecule and stimulating both the GLP‐1 and PYY receptor pathways have, in preclinical investigations, reduced food intake 99. Use of glucagon and GLP‐1 co‐agonists results in greater weight loss and improved glucose tolerance in obese rodents 100. In human studies, co‐administration of glucagon and GLP‐1 ameliorate hyperglycaemia and increase energy expenditure in combination with a reduction in food intake 101, 102; thus, combination therapy with several hormones may open up new avenues for treatment of obesity and T2D.

Conclusions

Structural differences between the various GLP‐1RAs result in unique clinical profiles; these treatments, therefore, differ from each other substantially with respect to glycaemic control, effects on weight, and safety and tolerability, as demonstrated in phase III head‐to‐head trials in T2D. These differences should be considered when selecting a GLP‐1RA for an individual patient. Patient preference should be an important element of the treatment decision. Data on patient preference for the GLP‐1RAs are currently limited, although glycaemic control and AEs are likely to be key factors 87.

The present review is limited by the small number of studies directly comparing the different GLP‐1RAs. Indeed, most of these studies have an open‐label design and have a relatively short duration of treatment in highly selected populations without major diabetes complications; therefore, long‐term endpoint studies are needed that assess safety and efficacy, and include larger numbers of patients treated with polypharmacy; these data would help to define the place of GLP‐1RAs in the T2D treatment algorithm.

The importance of the GLP‐1RA therapeutic class seems poised to increase in the treatment of T2D. Meanwhile, ongoing assessments of novel GLP‐1RAs and new delivery methods may lead to an even greater number of options in future.

Conflict of Interest

S. M. has served on advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Intarcia Therapeutics, Johnson & Johnson, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis Pharma, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi‐Aventis; received fees for speaking from AstraZeneca, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Merck, Sharp & Dohme, Novartis Pharma, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi‐Aventis; and received grants research from Novo Nordisk. S.M. researched, approved and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Watermeadow Medical for assistance with preparation of this manuscript (funded by Novo Nordisk).

References

- 1. UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group . Intensive blood‐glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet 1998; 352: 837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Golay A, Ybarra J. Link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005; 19: 649–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, a patient‐centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 1364–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Russell‐Jones D, Khan R. Insulin‐associated weight gain in diabetes–causes, effects and coping strategies. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007; 9: 799–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fonseca V. Effect of thiazolidinediones on body weight in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 2003; 115(Suppl. 8A): 42–48S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodmer M, Meier C, Krähenbühl S, Jick SS, Meier CR. Metformin, sulfonylureas, or other antidiabetes drugs and the risk of lactic acidosis or hypoglycemia: a nested case‐control analysis. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: 2086–2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Briscoe VJ, Davis SN. Hypoglycemia in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: physiology, pathophysiology, and management. Clin Diabetes 2006; 24: 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fowler MJ. Diabetes treatment, part 2: oral agents for glycemic management. Clin Diabetes 2007; 25: 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marathe CS, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Effects of GLP‐1 and incretin‐based therapies on gastrointestinal motor function. Exp Diabetes Res 2011; 2011: 279530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Geerlings S, Fonseca V, Castro‐Diaz D, List J, Parikh S. Genital and urinary tract infections in diabetes: impact of pharmacologically‐induced glucosuria. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2014; 103: 373–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shyangdan DS, Royle P, Clar C, Sharma P, Waugh N, Snaith A. Glucagon‐like peptide analogues for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 10: CD006423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rosenstock J, Raccah D, Korányi L et al. Efficacy and safety of lixisenatide once daily versus exenatide twice daily in type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on metformin: a 24‐week, randomized, open‐label, active‐controlled study (GetGoal‐X). Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2945–2951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dungan KM, Povedano ST, Forst T et al. Once‐weekly dulaglutide versus once‐daily liraglutide in metformin‐treated patients with type 2 diabetes (AWARD‐6): a randomised, open‐label, phase 3, non‐inferiority trial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pratley RE, Nauck MA, Barnett AH et al. Once‐weekly albiglutide versus once‐daily liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled on oral drugs (HARMONY 7): a randomised, open‐label, multicentre, non‐inferiority phase 3 study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Drucker DJ, Philippe J, Mojsov S, Chicko WL, Habener JF. Glucagon‐like peptide I stimulates insulin gene expression and increases cyclic AMP levels in a rat islet cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1987; 84: 3434–3438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holst JJ. The physiology of glucagon‐like peptide 1. Physiol Rev 2007; 87: 1409–1439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wick A, Newlin K. Incretin‐based therapies: therapeutic rationale and pharmacological promise for type 2 diabetes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2009; 21: 623–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kielgast U, Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Treatment of type 1 diabetic patients with glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) and GLP‐1R agonists. Curr Diabetes Rev 2009; 5: 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nauck MA, Kleine N, Ørskov C, Hoist JJ, Willms B, Creutzfeldt W. Normalization of fasting hyperglycaemia by exogenous glucagon‐like peptide 1 (7‐36 amide) in type 2 (non‐insulin dependent) diabetic patients. Diabetologia 1993; 36: 741–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rachman J, Barrow BA, Levy JC, Turner RC. Near‐normalisation of diurnal glucose concentrations by continuous administration of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) in subjects with NIDDM. Diabetologia 1997; 40: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zander M, Madsbad S, Madsen JL, Holst JJ. Effect of 6‐week course of glucagon‐like peptide 1 on glycaemic control, insulin sensitivity, and β‐cell function in type 2 diabetes: a parallel‐group study. Lancet 2002; 359: 824–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Meier JJ. GLP‐1 receptor agonists for individualized treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012; 8: 728–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. AstraZeneca UK Limited . Byetta. Summary of product characteristics May 2015. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐duration_Product_Information/human/000698/WC500051845.pdf Accessed 02 June 2015.

- 24. AstraZeneca UK Limited . Byetta 2015. Available from URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails Accessed 24 June 2015.

- 25. Novo Nordisk Limited . Victoza. Summary of product characteristics. May 2015. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/001026/WC500050017.pdf Accessed 2 June 2015.

- 26. Novo Nordisk Limited . Victoza 2015. Available from URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails Accessed 24 June 2015.

- 27. AstraZeneca UK Limited . Bydureon. Summary of product characteristics, June 2015. Available from URL: http://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community‐register/2011/20110617103730/anx_103730_en.pdf Accessed 2 June 2015.

- 28. AstraZeneca UK Limited . Bydureon 2015. Available from URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails Accessed 24 June 2015.

- 29. Sanofi . Lyxumia. Summary of product characteristics December 2014. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/002445/WC500140401.pdf Accessed 2 June 2015.

- 30. GlaxoSmithKline . Eperzan. Summary of product characteristics February 2015. Available from URL: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_‐_Product_Information/human/002735/WC500165117.pdf Accessed 2 June 2015.

- 31. FDA . FDA approves Tanzeum to treat type 2 diabetes April 15, 2014. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm393289.htm Accessed 25 May 2015.

- 32. Eli Lilly and Company Limited . Trulicity summary of product characteristics January 2015. Available from URL: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29747 Accessed 26 April 2015.

- 33. Eli Lilly and Company Limited . Trulicity 2015. Available from URL: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm?fuseaction=Search.DrugDetails Accessed 24 June 2015.

- 34. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient‐centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 140–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Garber AJ, Abrahamson MJ, Barzilay JI et al. AACE/ACE comprehensive diabetes management algorithm 2015. Endocr Pract 2015; 21: 438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Göke R, Fehmann HC, Linn T et al. Exendin‐4 is a high potency agonist and truncated exendin‐(9‐39)‐amide an antagonist at the glucagon‐like peptide 1‐(7‐36)‐amide receptor of insulin‐secreting beta‐cells. J Biol Chem 1993; 268: 19650–19655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sjöholm Å. Liraglutide therapy for type 2 diabetes: overcoming unmet needs. Pharmaceuticals 2010; 3: 764–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garber AJ. Long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists: a review of their efficacy and tolerability. Diabetes Care 2011; 34(Suppl. 2): S279–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kuritzky L. Safety and efficacy of dulaglutide, a once weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist, for the management of type 2 diabetes. Postgrad Med 2014; 126: 60–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rosenstock J, Balas B, Charbonnel B et al. The fate of taspoglutide, a weekly GLP‐1 receptor agonist, versus twice‐daily exenatide for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 498–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Donnelly D. The structure and function of the glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor and its ligands. Br J Pharmacol 2012; 166: 27–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. DeYoung MB, MacConell L, Sarin V, Trautmann M, Herbert P. Encapsulation of exenatide in poly‐(D,L‐lactide‐co‐glycolide) microspheres produced an investigational long‐acting once‐weekly formulation for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2011; 13: 1145–1154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Quianzon CCL, Shomal ME. Lixisenatide – once‐daily glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonist in the management of type 2 diabetes. Eur Endocrinol 2012; 8: 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Matthews JE, Stewart MW, De Boever EH et al. Pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics, safety, and tolerability of albiglutide, a long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 mimetic, in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 4810–4817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sebokova E, Christ AD, Wang H et al. Taspoglutide, an analog of human glucagon‐like peptide‐1 with enhanced stability and in vivo potency. Endocrinology 2010; 151: 2474–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reddy S, Park S, Fineman M et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of exenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes. AAPS J 2005; 7: M1285. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Fineman M, Flanagan S, Taylor K et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of exenatide extended‐release after single and multiple dosing. Clin Pharmacokinet 2011; 50: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elbrønd B, Jakobsen G, Larsen S et al. Pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of a single‐dose of NN2211, a long‐acting glucagon like peptide 1 derivative, in healthy male subjects. Diabetes Care 2002; 25: 1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Christensen M, Knop FK, Holst JJ, Vilsbøll T. Lixisenatide, a novel GLP‐1 receptor agonist for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. IDrugs 2009; 12: 503–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bush MA, Matthews JE, De Boever EH et al. Safety, tolerability, pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of albiglutide, a long‐acting glucagon‐like peptide‐1 mimetic, in healthy subjects. Diabetes Obes Metab 2009; 11: 498–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kapitza C, Heise T, Birman P, Jallet K, Ramis J, Balena R. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of taspoglutide, a once‐weekly, human GLP‐1 analogue, after single‐dose administration in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 1156–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Arnouts P, Boligano D, Nistor I et al. Glucose‐lowering drugs in patients with chronic kidney disease: a narrative review on pharmacokinetic properties. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 1284–1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Young MA, Wald JA, Matthews JE et al. Clinical pharmacology of albiglutide, a GLP‐1 receptor agonist. Postgrad Med 2014; 126: 84–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Drucker DJ, Buse JB, Taylor K et al. Exenatide once weekly versus twice daily for the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a randomised, open‐label, non‐inferiority study. Lancet 2008; 372: 1240–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Blevins T, Pullman J, Malloy J et al. DURATION‐5: exenatide once weekly resulted in greater improvements in glycemic control compared with exenatide twice daily in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 1301–1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ji L, Onishi Y, Ahn CW et al. Efficacy and safety of exenatide once‐weekly vs exenatide twice‐daily in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Invest 2013; 4: 53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Buse JB, Garber A, Rosenstock J et al. Liraglutide treatment is associated with a low frequency and magnitude of antibody formation with no apparent impact on glycemic response or increased frequency of adverse events: results from the liraglutide effect and action in diabetes (LEAD) trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: 1695–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fonseca VA, Alvarado‐Ruiz R, Raccah D et al. Efficacy and safety of the once‐daily GLP‐1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in monotherapy: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial in patients with type 2 diabetes (GetGoal‐Mono). Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ratner RE, Rosenstock J, Boka G. DRI6012 study investigators. Dose‐dependent effects of the once‐daily GLP‐1 receptor agonist lixisenatide in patients with type 2 diabetes inadequately controlled with metformin: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Diabet Med 2010; 27: 1024–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Fineman MS, Cirincione BB, Maggs D, Diamant M. GLP‐1 based therapies: differential effects on fasting and postprandial glucose. Diabetes Obes Metab 2012; 14: 675–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kapitza C, Forst T, Coester HV et al. Pharmacodynamic characteristics of lixisenatide once daily versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes insufficiently controlled on metformin. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 642–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Werner U. Effects of the GLP‐1 receptor agonist lixisenatide on postprandial glucose and gastric emptying–preclinical evidence. J Diabetes Complications 2014; 28: 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cho YM, Wideman RD, Kieffer TJ. Clinical application of glucagon‐like peptide 1 receptor agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocrinol Metab 2013; 28: 262–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Madsbad S. Exenatide and liraglutide: different approaches to develop GLP‐1 receptor agonists (incretin mimetics) – preclinical and clinical results. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 23: 463–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Madsbad S, Kielgast U, Asmar M, Deacon CF, Torekov SS, Holst JJ. An overview of once‐weekly glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists—available efficacy and safety data and perspectives for the future. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Buse JB, Rosenstock J, Sesti G et al. Liraglutide once a day versus exenatide twice a day for type 2 diabetes: a 26‐week randomised, parallel‐group, multinational, open‐label trial (LEAD‐6). Lancet 2009; 374: 39–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Buse JB, Nauck M, Forst T et al. Exenatide once weekly versus liraglutide once daily in patients with type 2 diabetes (DURATION‐6): a randomised, open‐label study. Lancet 2013; 381: 117–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Meier JJ, Rosenstock J, Hincelin‐Méry A et al. Contrasting effects of lixisenatide and liraglutide on postprandial glycemic control, gastric emptying, and safety parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes on optimized insulin glargine with or without metformin: a randomized, open‐label trial. Diabetes Care 2015; 38: 1263–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Gastaldelli A, Balas B, Ratner R et al. A direct comparison of long‐ and short‐acting GLP‐1 receptor agonists (taspoglutide once weekly and exenatide twice daily) on postprandial metabolism after 24 weeks of treatment. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Vilsbøll T, Christensen M, Junker AE, Knop FK, Gluud LL. Effects of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 receptor agonists on weight loss: systematic review and meta‐analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2012; 344: d7771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Niswender K, Pi‐Sunyer X, Buse J et al. Weight change with liraglutide and comparator therapies: an analysis of seven phase 3 trials from the liraglutide diabetes development programme. Diabetes Obes Metab 2013; 15: 42–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Madsbad S. The role of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 impairment in obesity and potential therapeutic implications. Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Secher A, Jelsing J, Baquero AF et al. The arcuate nucleus mediates GLP‐1 receptor agonist liraglutide‐dependent weight loss. J Clin Invest 2014; 124: 4473–4488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Robinson LE, Holt TA, Rees K, Randeva HS, O'Hare JP. Effects of exenatide and liraglutide on heart rate, blood pressure and body weight: systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ Open 2013; 3: e001986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Buse JB, Drucker DJ, Taylor KL et al. DURATION‐1: exenatide once weekly produces sustained glycemic control and weight loss over 52 weeks. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1255–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Buse JB, Sesti G, Schmidt SE et al. Switching to once‐daily liraglutide from twice‐daily exenatide further improves glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes using oral agents. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 1300–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Pyke C, Heller RS, Kirk RK et al. GLP‐1 receptor localization in monkey and human tissue: novel distribution revealed with extensively validated monoclonal antibody. Endocrinology 2014; 155: 1280–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fonseca VA, Devries JH, Henry RR et al. Reductions in systolic blood pressure with liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes: insights from a patient‐level pooled analysis of six randomized clinical trials. J Diabetes Complications 2014; 28: 399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Nauck MA, Friedrich N. Do GLP‐1–based therapies increase cancer risk? Diabetes Care 2013; 36(Suppl. 2): S245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Butler PC, Elashoff M, Elashoff R, Gale EAM. A critical analysis of the clinical use of incretin‐based therapies: are the GLP‐1 therapies safe? Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2118–2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Egan AG, Blind E, Dunder K et al. Pancreatic safety of incretin‐based drugs – FDA and EMA assessment. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 794–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Nainggolan L. No CV benefit with lixisenatide in ELIXA, but results reassure. Medscape Multispecialty 2015. Available from URL: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/846074 Accessed on 17 September 2015.

- 83. Garbutt JC, Kranzler HR, O'Malley SS et al. Efficacy and tolerability of long‐acting injectable naltrexone for alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293: 1617–1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Johnson BA. Naltrexone long‐acting formulation in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Ther Clin Risk Manage 2007; 3: 741–749. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Schnabel CA, Fineberg SE, Kim DD. Immunogenicity of xenopeptide hormone therapies. Peptides 2006; 27: 1902–1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Best JH, Boye KS, Rubin RR, Cao D, Kim TH, Peyrot M. Improved treatment satisfaction and weight‐related quality of life with exenatide once weekly or twice daily. Diabet Med 2009; 26: 722–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Polster M, Zanutto E, McDonald S, Conner C, Hammer M. A comparison of preferences for two GLP‐1 products – liraglutide and exenatide – for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Med Econ 2010; 13: 655–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Hessler D, Bruhn D, Best JH. Patient perspectives on once‐weekly medications for diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. McKay M, Compion G, Lytzen L. A comparison of insulin injection needles on patients' perceptions of pain, handling, and acceptability: a randomized, open‐label, crossover study in subjects with diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther 2009; 11: 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ahren B. The future of incretin‐based therapy: novel avenues—novel targets. Diabetes Obes Metab 2011; 13: 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Kuritzky L. Overcoming barriers to insulin replacement. J Fam Pract 2009; 58(8 Suppl.): S25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Henry RR, Rosenstock J, Logan DK et al. Randomized trial of continuous subcutaneous delivery of exenatide by ITCA 650 versus twice‐daily exenatide injections in metformin‐treated type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2013; 36: 2559–2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Barnett AH. Complementing insulin therapy to achieve glycemic control. Adv Ther 2013; 30: 557–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Buse JB, Bergenstal RM, Glass LC et al. Use of twice‐daily exenatide in basal insulin–treated patients with type 2 diabetes a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2011; 154: 103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Mathieu C, Rodbard HW, Cariou B et al. A comparison of adding liraglutide versus a single daily dose of insulin aspart to insulin degludec in subjects with type 2 diabetes (BEGIN: VICTOZA ADD‐ON). Diabetes Obes Metab 2014; 16: 636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Gough SC, Bode B, Woo V et al. Efficacy and safety of a fixed‐ratio combination of insulin degludec and liraglutide (IDegLira) compared with its components given alone: results of a phase 3, open‐label, randomised, 26‐week, treat‐to‐target trial in insulin‐naive patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2: 885–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Harrison LB, Mora PF, Clark GO, Lingvay I. Type 1 diabetes treatment beyond insulin: role of GLP‐1 analogs. J Investig Med 2013; 61: 40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Kielgast U, Krarup T, Holst JJ, Madsbad S. Four weeks of treatment with liraglutide reduces insulin dose without loss of glycemic control in type 1 diabetic patients with and without residual B‐cell function. Diabetes Care 2011; 34: 1463–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. De Silva A, Salem V, Long CJ et al. The gut hormones PYY3‐36 and GLP‐17‐36 amide reduce food intake and modulate brain activity in appetite centers in humans. Cell Metab 2011; 14: 700–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Day JW, Ottaway N, Patterson JT et al. A new glucagon and GLP‐1 co‐agonist eliminates obesity in rodents. Nat Chem Biol 2009; 10: 749–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Tan TM, Field BC, McCullough KA et al. Coadministration of glucagon‐like peptide‐1 during glucagon infusion in humans results in increased energy expenditure and amelioration of hyperglycemia. Diabetes 2013; 62: 1131–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Cegla J, Troke RC, Jones B et al. Co‐infusion of low‐dose glucagon‐like peptide‐1 (GLP‐1) and glucagon in man results in a reduction in food intake. Diabetes 2014; 63: 3711–3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]