Summary

The milk fat globule (MFG) is one of the most representative of mammary gland tissues and can be utilized to study gene expression of lactating cows during lactation. In this study, RNA‐seq technology was employed to detect differential expression of genes in MFGs at day 10 and day 70 after calving between two groups of cows with extremely high (H group) and low (L group) 305‐day milk yield, milk fat yield and milk protein yield. In total, 1232, 81, 429 and 178 significantly differentially expressed genes (false discovery rate q < 0.05) were detected between H10 and L10, H70 and L70, H10 and H70, and L10 and L70 respectively. Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis revealed that these differentially expressed genes were enriched in biological processes involved in mammary gland development, protein and lipid metabolism process, signal transduction, cellular process, differentiation and immune function. Among these differentially expressed genes, 178 (H10 vs. L10), 4 (H70 vs. L70), 68 (H10 vs. H70) and 22 (L10 vs. L70) were found to be located within previously reported QTL regions for milk production traits. Based on these results, some promising candidate genes for milk production traits in dairy cattle were suggested.

Keywords: differentially expressed genes, milk fat globules, milk production traits, RNA sequencing

Introduction

The mammary gland is the only organ that undergoes regular proliferation and involution cycles after maturity (Gao et al. 2013). Mammary epithelial cells (MECs) are unique in that they synthesize and secrete milk (Canovas et al. 2014). Knowledge of the molecular events in mammary epithelium cells during lactation would contribute to the development of new technologies in the management and breeding of dairy cattle. Numerous studies on gene expression in the bovine mammary gland have been carried out by performing mammary biopsies, which is invasive and costly and disturbs the normal lactation process. In addition, studies of metabolism in bovine mammary tissue are complicated due to the presence of multiple cell types within the gland, such as adipocytes, fibroblasts, blood vessels and immune cells (Dulbecco et al. 1982; Maningat et al. 2009; Van Keymeulen et al. 2011).

During lactation, milk fat is synthesized in MECs (Lemay et al. 2007). MECs secrete fat into milk via an apocrine mechanism along with a crescent of the MEC cytoplasm enveloped in plasma membrane, resulting in the secretion of milk fat globules (MFGs) (Patton & Huston 1988; McManaman et al. 2004). Intracellular components of the MECs become trapped within the MFGs (Huston & Patton 1990). Thus, the RNA from MFGs is expected to represent RNA from MECs at the time they are producing milk, as demonstrated by a number of previous studies (Maningat et al. 2007, 2009; Brenaut et al. 2012). Canovas et al. (2014) also suggested that the MFG transcriptome is the most representative of the transcriptome of mammary gland tissue and laser microdissected MECs. Therefore, MFGs in milk can be utilized as effective and easily obtainable sources to study gene expression during lactation.

In the current study, we examined differential expression of genes in MFGs of lactating cows with remarkably different milk production performance using RNA sequencing (RNA‐seq) technology.

Materials and methods

Animals and milk samples

Based on their milk production records in their previous lactation, six Chinese Holstein cows, of which three were in their second and three in their third lactation, were selected from the Beijing Sanyuanlvhe Dairy Farm. The six cows were divided into two groups, the H group and L group, each with three cows according to their performance in their previous lactation. The cows in the H group had higher 305‐day milk yield (MY > 11 000 kg), fat yield (FY > 410 kg) and protein yield (PY > 340 kg), whereas cows in the L group had lower MY, FY and PY (<8600 kg, 360 kg and 300 kg respectively). Detailed information about the six cows is shown in Table 1. The age differences among the three cows in the second lactation and among the three cows in the third lactation were less than 45 days and less than 20 days respectively. Among the six cows, there were two pairs of half sibs, each pair consisting of one H cow and one L cow. The other two cows, one H and one L cow, were non‐sibs.

Table 1.

Information about animals used in this study

| Animala | Parity | 305‐day milk yield (kg) | Milk fat yield (kg) | Milk protein yield (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H‐1 | 3 | 12 514 | 472.28 | 394.19 |

| H‐2 | 3 | 12 966 | 466.78 | 414.91 |

| H‐3 | 2 | 11 222 | 419.70 | 345.64 |

| L‐1 | 3 | 8565 | 358.87 | 298.06 |

| L‐2 | 2 | 6184 | 267.77 | 207.16 |

| L‐3 | 2 | 7837 | 355.02 | 282.13 |

H‐1 to H‐3, animals in the H (high yield) group; L‐1 to L‐3, animals in the L (low yield) group.

Milk samples were collected from these cows at two lactation stages: the early stage (days in milk = 10) and peak stage (days in milk = 70). Hereafter, cows of the H group at early stage and peak stage are referred to as H10 and H70 respectively, and cows of the L group at early stage and peak stage are referred to as L10 and L70 respectively. Milk samples were collected into sterile, RNase‐free bottles before the morning milking and then kept on ice prior to the MFG collection.

Collection of MFGs

Approximately 45 ml of milk was transferred into sterile, RNase‐free 50‐ml tubes and then centrifuged (Eppendorf, Germany) at 3000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant fat layer was transferred into a new, RNase‐free, pre‐weighed 15‐ml tube using an RNase‐free spoon. Twelve milliliters (12 ml) of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technology) was added to dissolve the fat layer prior to storing at −80 °C.

RNA isolation and sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from the 12 milk samples. RNA isolation was performed using the RNeasy method (Qiagen), following the manufacturer's protocols. RNA concentration was measured via a ND‐2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The quality of the total RNA was evaluated using the RNA integrity number (RIN) value in an Agilent Technologies 2100 Bioanalyzer. The RIN value of each sample was around 7.0. Messenger RNA was isolated and purified using a Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit (Invitrogen Life Technology). Then, mRNA was fragmented and first‐ and second‐strand cDNA were synthesized. After end repair and adapter ligation, a 400‐ to 500‐bp fragment size was selected by gel excision and each sample was individually sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq 2500 platform.

Detection of differentially expressed genes

Based on the bovine reference genome (UMD3.1) (ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-72/fasta/bos_taurus/dna/) and the corresponding gene model annotation files (ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-72/gtf/bos_taurus/), clean reads for each sample were mapped to the reference genome by tophat (v2.0.10) and assembled by cufflinks (v2.1.1) (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/). Then, cuffdiff, which is included in the cufflinks package, was used to detect differentially expressed genes and transcripts between the H and L groups at the same stage of lactation (H10 vs. L10, H70 vs. L70) as well as between early and peak stage of lactation in the same group (H10 vs. H70, L10 vs. L70). A significantly differential expression was declared if the q‐value (false discovery rate corrected P‐values) was <0.05. In addition, we performed Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis and pathway analysis of the differentially expressed genes using david software v6.7 (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/). The GO terms and pathways were considered significant if their Benjamini corrected P‐values were <0.05.

Results

Mapping and annotation

After removal of sequencing adaptors and low‐complexity reads, we acquired 60 204 905–93 829 745 paired‐end reads per sample. tophat software (http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat/index.shtml) was employed to map the reads against the bovine reference genome. The observed percentages of mapped reads per sample were around 64.17–75.61%, and the percentages of unique aligned reads per sample were around 65.92–89.97% (Table S1). picard (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/) was used to calculate the proportion of reads mapping to coding regions, introns, 5′‐/3′‐UTR regions and intergenic regions. As expected, the highest percentage of reads mapped to coding regions (70.83–80.74%), whereas 16.34–21.72% mapped to 5′‐/3′‐UTR regions, 2.81–10.50% mapped to intergenic regions and only 0.11–0.62% mapped to introns (Table S2). All the raw sequence data were deposited in SRA (GenBank Accession number SRP064718).

Differentially expressed genes between H and L groups

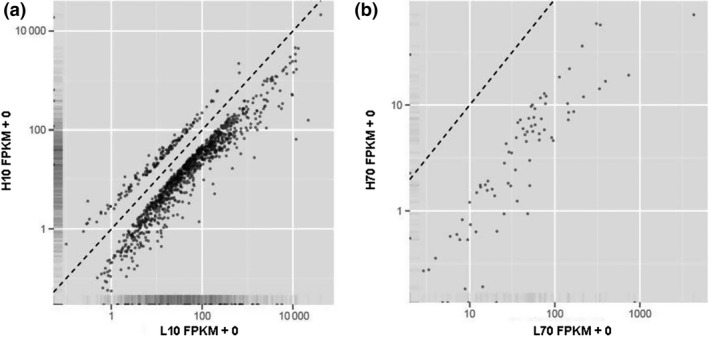

In total, 1232 significantly differentially expressed genes were detected between H10 and L10, whereas only 81 genes were identified to be significantly differentially expressed between H70 and L70 (Table 2). Most of the differentially expressed genes (1076 of 1232 and 78 of 81 respectively) showed higher expression in the cows of the L group (Fig. 1). Furthermore, of the 81 genes differentially expressed between H70 and L70, 71 were also differentially expressed between H10 and L10. Details of the differentially expressed genes are shown in Tables S3 and S4.

Table 2.

Summary of the differentially expressed (DE) genes in the four comparisons

| Comparisona | No. DE genes | Upregulated genes in L group or at early stage |

|---|---|---|

| H10 vs. L10 | 1232 | 1076 (87.3%) |

| H70 vs. L70 | 81 | 78 (96.3%) |

| H10 vs. H70 | 429 | 220 (51.3%) |

| L10 vs. L70 | 178 | 162 (91.0%) |

H and L refer to the high‐yield and low‐yield group respectively; 10 and 70 refer to the early (days in milk = 10) and peak (days in milk = 70) stage of lactation respectively.

Figure 1.

Differential expression of genes between the high (H) and low (L) groups. FPKM values under (above) the dotted line represent higher expression in the L(H) group. (a) H10 vs. L10; (b): H70 vs. L70.

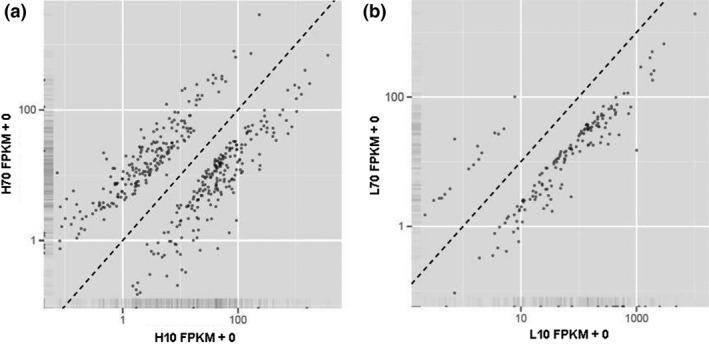

Differentially expressed genes between early and peak stages of lactation

In the H group, 429 genes were identified to be significantly differentially expressed between the early and peak stages of lactation, 220 (51.3%) of which were downregulated at the peak stage of lactation (Table 2, Fig. 2a). In the L group, 178 genes were significantly differentially expressed between the early and peak stages of lactation, and 162 (91.01%) of them showed lower expression at the peak stage of lactation (Table 2, Fig. 2b). In addition, 90 significantly differentially expressed genes overlapped between the two comparisons. Details of the differentially expressed genes are shown in Tables S5 and S6.

Figure 2.

Differential expression of genes between the early (days in milk = 10) and peak (days in milk = 70) stage of lactation. FPKM values under (above) the dotted line represent higher expression at the early (peak) stage of lactation. (a) H10 vs. H70; (b) L10 vs. L70.

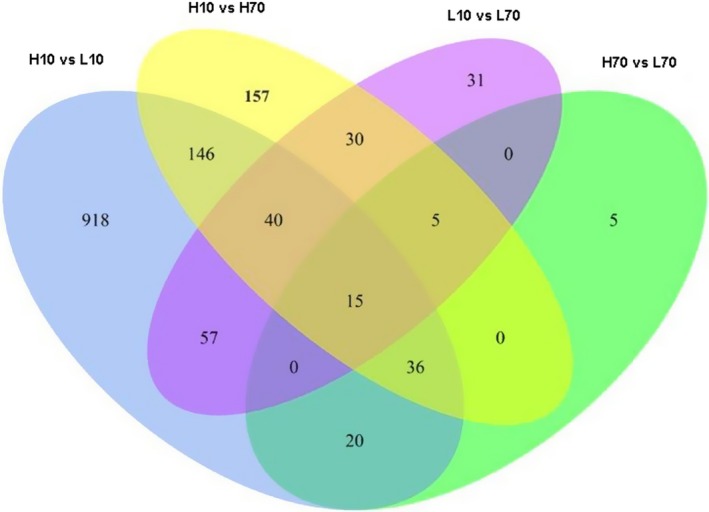

Distribution of differentially expressed genes

The distribution of the differentially expressed genes in the four comparisons (H10 vs. L10, H70 vs. L70, H10 vs. H70 and L10 vs. L70) is shown in Fig. 3. The largest number of differentially expressed genes was observed between H10 and L10, whereas the smallest number was observed between H70 and L70. Fifteen of the differentially expressed genes (Fig. 3) were detected in all four comparisons.

Figure 3.

Overlapping of differentially expressed genes from the four comparisons (H10 vs. L10, H70 vs. L70, H10 vs. H70 and L10 vs. L70).

Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis

The GO enrichment analysis of the differentially expressed genes revealed 55, 4 and 29 significant GO terms (Benjamini corrected P < 0.05) for the comparisons of H10 vs. L10, H70 vs. L70 and H10 vs. H70 respectively (Tables S7–S9). These GO terms are involved in mammary gland development, protein and lipid metabolism process, signal transduction, cellular process, differentiation and immune function. At the same time, the pathway analysis revealed two significant pathways, bta04060 (cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction) for H70 vs. L70 (Table S8) and bta04621 (NOD‐like receptor signaling pathway) for H10 vs. H70 (Table S9).

Integrated analysis of RNA‐seq and animal QTLdb

We integrated the differentially expressed genes and the QTL (quantitative trait loci) for milk production traits collected in the QTLdb database (http://www.animalgenome.org/cgi-bin/QTLdb/BT/index), which were detected by either QTL mapping studies or genome‐wide association studies (GWAS), by comparing their chromosome positions in order to gain further insights into the association of the differentially expressed genes with milk production traits. For QTL detected by QTL mapping studies, only those with a confidence interval less than 1 Mb were considered as a QTL region. For QTL revealed by GWAS, the 200 kb upstream/downstream of the significant SNP were defined as a QTL region. Among the differentially expressed genes from the four comparisons, 178 (H10 vs. L10), 4 (H70 vs. L70), 68 (H10 vs. H70) and 22 (L10 vs. L70) genes were found to be located within QTL regions (Table S10).

Discussion

To identify candidate genes for milk production traits, it is important to reveal the transcriptome profiles of MECs during lactation. Most of previous studies on gene expression during lactation in dairy cattle were based on mammary gland tissue taken by mammary biopsy (Hou et al. 2010; Gao et al. 2013). However, the mammary gland tissue contains not only MECs but also myoepithelial cells and mesenchymal cells, including adipocytes, fibroblasts, blood vessels and immune cells (Dulbecco et al. 1982; Van Keymeulen et al. 2011). Thus, RNA isolated from mammary gland tissue dose not accurately describe the gene expression in mammary epithelium cells. In contrast, MFGs come solely from MECs (Maningat et al. 2009); therefore, RNA isolated from MFGs is better representative of RNA than that from MECs. Furthermore, for studying gene expression during lactation, using MFGs is much easier than using MECs because MFGs can be easily collected at any time during lactation, whereas collecting mammary gland tissue by mammary biopsy is invasive and costly and disturbs the normal lactation process.

A large number of differentially expressed genes were identified by RNA‐seq. Most of the differentially expressed genes showed lower expression in the cows with higher MY, FY and PY, that is, cows in the H group or at the peak stage (Table 2). In particular, 91.01% of the differentially expressed genes between L10 and L70 showed lower expression at the peak stage of lactation. Similar results were obtained by Cui et al. (2014), who studied the differential expression of genes in mammary gland tissue of lactating cows with extremely high and low fat and protein percentage. They found that most of the differentially expressed genes (28 of 31) were downregulated in the cows with higher fat and protein percentage. This is consistent with our results given that fat and protein percentage are positively correlated with FY and PY respectively. It has been commonly observed in bovine (Finucane et al. 2008; Bionaz et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2013) as well as in other mammals (Rosen et al. 1975; Shuster et al. 1976; Robinson et al. 1995; Rijnkels et al. 1997) that many more differentially expressed genes are downregulated than are upregulated in mammary gland in early lactation compared to in late pregnancy. It was also noted that these downregulated genes are largely involved in cell division, cell cycle and their related processes. Because the mammary gland cell proliferation occurs mainly in late pregnancy period and almost ceases during the lactation period (Sorensen et al. 2006), it is reasonable to expect that many genes involved in cell proliferation and other related biological processes may be already expressed at a high plateau level at the late pregnant stage and decrease their expression or turn off in the lactation period. This explanation may also apply to our observation, that is, that most of the differentially expressed genes showed lower expression in the cows with higher milk production performance. Most of these downregulated genes were also enriched in cell process, activation, communication and proliferation. Their decreased expression may be coupled with increased expression of genes involved in metabolism and transporter activities, leading to higher milk production performance.

The GO enrichment analysis revealed that the differentially expressed genes are enriched in a large number of GO terms; some of them are involved in mammary gland development, protein and lipid metabolism process, signal transduction, cell cycle/death, differentiation and immune function. Here, we focus on two of these GO terms, GO:0006631 (fatty acid metabolic process) and GO:0030879 (mammary gland development), which are more likely related to milk production traits due to their biological function. Differentially expressed genes included in these two terms are presented in Table 3. Among these genes, STAT5A, PRLR, NCF1 and PTGES are located within reported QTL regions (Table S10) and are considered promising candidate genes for milk production traits. STAT5A is a mediator of prolactin signaling in MECs and is known to play a role in lactogenesis (Wheeler et al. 2001). Khatib et al. (2008) reported the association of the bovine STAT5A gene with fertilization success, embryonic survival and milk composition. Liu et al. (1997) found that STAT5A–/– mice were normal in appearance, size, weight and fertility, whereas their mammary development was impaired and females failed to lactate. PRLR is a specific membrane receptor for the prolactin hormone (PRL), which plays an important regulatory function in mammary gland development, expression of milk protein genes and lactation (Kelly et al. 2002). Kelly et al. (2001, 2002) found that homozygous PRLR knockout mice (PRLR–/–) were completely infertile due to a complete failure of blastocysts to implant and lack of normal mammary development. In progesterone‐treated mice, pregnancy was rescued but the mammary gland was severely underdeveloped. NCF1 is involved in inflammatory response. Efimova et al. (2011) found that NCF1 was essential for direct regulatory T‐cell‐mediated suppression of CD4+ effector T cells. PTGES is a member of the membrane‐associated proteins in the eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism family and involved in arachidonic acid metabolism (Mancini et al. 2001).

Table 3.

Differentially expressed genes in GO:0030879 and GO:0006631

| GO term | Differentially expressed genes |

|---|---|

| GO:0030879—mammary gland development | IRF6, AGPAT6, STAT5A, XDH, B4GALT1, BCL2L11, PRLR |

| GO:0006631—fatty acid metabolic process | PRKAA1, NCF1, AGPAT6, STAT5A, CRYL1, GPAM, ALOX12, PGHS‐2, PRKAR2B, CPT1B, SLC27A1, FADS6, PPARD, ACACA, PTGES, EHHADH, ALOX5 |

GO, Gene Ontology.

Although the other genes in these two terms are not located within the reported QTL regions, they may also be good candidate genes for milk production traits. For example, AGPAT6 encodes a protein that is involved in both fatty acid metabolic process and mammary gland development and belongs to the 1‐acylglycerol‐3‐phosphate O‐acyltransferase (AGPAT) family. Beigneux et al. (2006) reported that the alveoli and ducts of lactating mammary glands of AGPAT6–/– mice were underdeveloped. Also, AGPAT6–/– mice had a significant decrease in the size and number of lipid droplets within the MECs and ducts. In addition, the milk from AGPAT6–/– mice was markedly reduced in diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol. These observations indicated that AGPAT6 is crucial for milk production. In addition, the genes EHHADH, FADS6, ALOX5, ALOX12 and ACACA are all involved in fatty acid synthesis and metabolism (Horrobin 1993; Mehrabian et al. 2008; Houten et al. 2012; Matsumoto et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2012; Habermann et al. 2013).

In conclusion, the present study provided important information on differentially expressed genes between cows with high and low milk production performance at early and peak stage of lactation using RNA‐seq technology and RNA from MFGs. Integrated analysis of differential gene expression, QTL/GWAS data and GO enrichment analysis suggested that some of the differentially expressed genes could be considered promising candidate genes for milk production traits in dairy cattle.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supporting information

Table S1 Numbers of reads obtained and percentages of mapped reads per sample

Table S2 Proportions of reads mapping to coding, intron, 5′/3′UTR or intergenic regions

Table S3 Details of differentially expressed genes between H10 and L10

Table S4 Details of differentially expressed genes between H70 and L70

Table S5 Details of differentially expressed genes between H10 and H70

Table S6 Details of differentially expressed genes between L10 and L70

Table S7 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H10 and L10

Table S8 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H70 and L70

Table S9 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H10 and H70

Table S10 Details of differentially expressed genes located within reported QTL regions for milk production traits

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (31201772), the 948 Program of the Ministry of Agriculture of China (2011‐G2A(3)), the Program of New Breed Development via Transgenic Technology (2014ZX0800953B) and Chinese Universities Scientific Fund (2014XJ003).

References

- Beigneux A.P., Vergnes L., Qiao X. et al (2006) Agpat6 – a novel lipid biosynthetic gene required for triacylglycerol production in mammary epithelium. Journal of Lipid Research 47, 734–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bionaz M., Periasamy K., Rodriguez‐Zas S.L., Everts R.E., Lewin H.A., Hurley W.L. & Loor J.J. (2012) Old and new stories: revelations from functional analysis of the bovine mammary transcriptome during the lactation cycle. PLoS One 7, e33268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenaut P., Bangera R., Bevilacqua C., Rebours E., Cebo C. & Martin P. (2012) Validation of RNA isolated from milk fat globules to profile mammary epithelial cell expression during lactation and transcriptional response to a bacterial infection. Journal of Dairy Science 95, 6130–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canovas A., Rincon G., Bevilacqua C. et al (2014) Comparison of five different RNA sources to examine the lactating bovine mammary gland transcriptome using RNA‐sequencing. Scientific Reports 4, 5297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X., Hou Y., Yang S., Xie Y., Zhang S., Zhang Y., Zhang Q., Lu X., Liu G.E. & Sun D. (2014) Transcriptional profiling of mammary gland in Holstein cows with extremely different milk protein and fat percentage using RNA sequencing. BMC Genomics 15, 226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulbecco R., Henahan M. & Armstrong B. (1982) Cell types and morphogenesis in the mammary gland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 79, 7346–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efimova O., Szankasi P. & Kelley T.W. (2011) Ncf1 (p47phox) is essential for direct regulatory T cell mediated suppression of CD4+ effector T cells. PLoS One 6, e16013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finucane K.A., McFadden T.B., Bond J.P., Kennelly J.J. & Zhao F.Q. (2008) Onset of lactation in the bovine mammary gland: gene expression profiling indicates a strong inhibition of gene expression in cell proliferation. Functional & Integrative Genomics 8, 251–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y., Lin X., Shi K., Yan Z. & Wang Z. (2013) Bovine mammary gene expression profiling during the onset of lactation. PLoS One 8, e70393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habermann N., Ulrich C.M., Lundgreen A. et al (2013) PTGS1, PTGS2, ALOX5, ALOX12, ALOX15, and FLAP SNPs: interaction with fatty acids in colon cancer and rectal cancer. Genes Nutrition 8, 115–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrobin D.F. (1993) Fatty acid metabolism in health and disease: the role of delta‐6‐desaturase. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 57, 732S–6S; discussion 6S‐7S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou X., Li Q. & Huang T. (2010) Microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in the bovine mammary gland during lactation. Science China Life Sciences 53, 248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houten S.M., Denis S., Argmann C.A., Jia Y., Ferdinandusse S., Reddy J.K. & Wanders R.J. (2012) Peroxisomal L‐bifunctional enzyme (Ehhadh) is essential for the production of medium‐chain dicarboxylic acids. Journal of Lipid Research 53, 1296–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston G.E. & Patton S. (1990) Factors related to the formation of cytoplasmic crescents on milk fat globules. Journal of Dairy Science 73, 2061–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.A., Binart N., Lucas B., Bouchard B. & Goffin V. (2001) Implications of multiple phenotypes observed in prolactin receptor knockout mice. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 22, 140–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly P.A., Bachelot A., Kedzia C., Hennighausen L., Ormandy C.J., Kopchick J.J. & Binart N. (2002) The role of prolactin and growth hormone in mammary gland development. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 197, 127–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib H., Monson R.L., Schutzkus V., Kohl D.M., Rosa G.J. & Rutledge J.J. (2008) Mutations in the STAT5A gene are associated with embryonic survival and milk composition in cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 91, 784–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemay D.G., Neville M.C., Rudolph M.C., Pollard K.S. & German J.B. (2007) Gene regulatory networks in lactation: identification of global principles using bioinformatics. BMC Systems Biology 1, 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Robinson G.W., Wagner K.U., Garrett L., Wynshaw‐Boris A. & Hennighausen L. (1997) Stat5a is mandatory for adult mammary gland development and lactogenesis. Genes & Development 11, 179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancini J.A., Blood K., Guay J., Gordon R., Claveau D., Chan C.C. & Riendeau D. (2001) Cloning, expression, and up‐regulation of inducible rat prostaglandin e synthase during lipopolysaccharide‐induced pyresis and adjuvant‐induced arthritis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 276, 4469–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maningat P.D., Sen P., Sunehag A.L., Hadsell D.L. & Haymond M.W. (2007) Regulation of gene expression in human mammary epithelium: effect of breast pumping. Journal of Endocrinology 195, 503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maningat P.D., Sen P., Rijnkels M., Sunehag A.L., Hadsell D.L., Bray M. & Haymond M.W. (2009) Gene expression in the human mammary epithelium during lactation: the milk fat globule transcriptome. Physiological Genomics 37, 12–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto H., Sasaki K., Bessho T., Kobayashi E., Abe T., Sasazaki S., Oyama K. & Mannen H. (2012) The SNPs in the ACACA gene are effective on fatty acid composition in Holstein milk. Molecular Biology Reports 39, 8637–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManaman J.L., Palmer C.A., Anderson S., Schwertfeger K. & Neville M.C. (2004) Regulation of milk lipid formation and secretion in the mouse mammary gland. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 554, 263–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabian M., Schulthess F.T., Nebohacova M., Castellani L.W., Zhou Z., Hartiala J., Oberholzer J., Lusis A.J., Maedler K. & Allayee H. (2008) Identification of ALOX5 as a gene regulating adiposity and pancreatic function. Diabetologia 51, 978–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton S. & Huston G.E. (1988) Incidence and characteristics of cell pieces on human milk fat globules. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 965, 146–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rijnkels M., Wheeler D.A., de Boer H.A. & Pieper F.R. (1997) Structure and expression of the mouse casein gene locus. Mammalian Genome 8, 9–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson G.W., McKnight R.A., Smith G.H. & Hennighausen L. (1995) Mammary epithelial cells undergo secretory differentiation in cycling virgins but require pregnancy for the establishment of terminal differentiation. Development 121, 2079–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen J.M., Woo S.L. & Comstock J.P. (1975) Regulation of casein messenger RNA during the development of the rat mammary gland. Biochemistry 14, 2895–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuster R.C., Houdebine L.M. & Gaye P. (1976) Studies on the synthesis of casein messenger RNA during pregnancy in the rabbit. European Journal of Biochemistry 71, 193–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen M.T., Norgaard J.V., Theil P.K., Vestergaard M. & Sejrsen K. (2006) Cell turnover and activity in mammary tissue during lactation and the dry period in dairy cows. Journal of Dairy Science 89, 4632–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Keymeulen A., Rocha A.S., Ousset M., Beck B., Bouvencourt G., Rock J., Sharma N., Dekoninck S. & Blanpain C. (2011) Distinct stem cells contribute to mammary gland development and maintenance. Nature 479, 189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.C., Gray N.E., Kuo T. & Harris C.A. (2012) Regulation of triglyceride metabolism by glucocorticoid receptor. Cell & Bioscience 2, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler T.T., Broadhurst M.K., Sadowski H.B., Farr V.C. & Prosser C.G. (2001) Stat5 phosphorylation status and DNA‐binding activity in the bovine and murine mammary glands. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 176, 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Numbers of reads obtained and percentages of mapped reads per sample

Table S2 Proportions of reads mapping to coding, intron, 5′/3′UTR or intergenic regions

Table S3 Details of differentially expressed genes between H10 and L10

Table S4 Details of differentially expressed genes between H70 and L70

Table S5 Details of differentially expressed genes between H10 and H70

Table S6 Details of differentially expressed genes between L10 and L70

Table S7 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H10 and L10

Table S8 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H70 and L70

Table S9 Summary of the Gene Ontology enrichment and pathway analysis of differentially expressed genes between H10 and H70

Table S10 Details of differentially expressed genes located within reported QTL regions for milk production traits