Abstract

Context:

A distressing pre-occupation with an imagined or slight defect in appearance with a marked negative effect on the patient's life is the core symptom of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD).

Aim:

To screen the patients attending a dermatology clinic at a tertiary care centre for BDD using the BDD-dermatology version (DV) questionnaire.

Settings and Design:

This cross-sectional study enrolled 245 consecutive patients from the dermatology outpatients clinic.

Methods:

The demographic details were collected and the DV of BDD screening questionnaire was administered. A 5-point Likert scale was used for objective scoring of the stated concern and patients who scored ≥3 were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The results were statistically analysed. Differences between the groups were investigated by Chi-square analysis for categorical variables, and Fisher exact test wherever required.

Results:

A total of 177 patients completed the study, and of these, eight patients screened positive for BDD. The rate of BDD in patients presenting with cosmetic complaints was 7.5% and in those with general dermatology, complaints were 2.1%, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.156). Facial flaws (62.5%) were the most common concern followed by body asymmetry (25%).

Conclusion:

The rates of BDD found in this study are comparable but at a lower rate than that reported in literature data.

KEYWORDS: Body dysmorphic disorder, cosmetic procedures, dysmorphophobia, screening questionnaire

INTRODUCTION

The upsurge of cosmetic procedures places the dermatologist and cosmetic surgeon in a unique position to identify patients suffering from body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). BDD is a distressing and impairing pre-occupation with an imagined or slight defect in appearance.[1] The marked negative effect on the patient's social and professional life differentiates BDD from simple concern.[2] The reported rates of suicidal ideation of 57.8% in BDD patients[3] alerts the clinician to the gravity of identifying patients of BDD.

Although BDD is primarily a psychiatric condition, patients with BDD are more likely to present to a dermatologist and/or plastic surgeon than to a psychiatrist.[4,5] The prevalence of BDD is estimated to be 1.8–2.4%[6,7] in the general population and tends to be higher in specific medical populations such as those attending dermatology and cosmetic clinics.[8] Because patients are typically ashamed of and embarrassed by their symptoms, they usually do not reveal them to clinicians unless specifically asked.[8] To diagnose a case of BDD, the patients should satisfy the criteria laid out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 criteria.[8] However, a simple questionnaire such as the BDD questionnaire-dermatology version (BDD-DV)[9] has been found to be reliable and valid for screening for BDD.

This study aims to screen the patients attending a dermatology clinic at a tertiary care centre for BDD using the BDD-DV questionnaire. To the best of our knowledge, a study assessing the prevalence of BDD in dermatology outpatients has not been done in India.

METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Dermatology Department of a tertiary care centre and enroled 245 consecutive patients who were seen in the dermatology outpatient clinic between April and May 2015. Patients aged <18 and >65 years were excluded from the study. The Dermatology Department of the hospital deals with both general and cosmetic dermatology patients and performs minimally invasive procedures.

The basic demographic details of the patients, clinical diagnosis, any previous cosmetic procedures, level of satisfaction with the treatments received and history of psychiatric illness were recorded. Next, the BDD questionnaire-DV was administered to the included patients in the regional language by researcher 1. This questionnaire was developed and validated by Dufresne et al.[9] and has been shown to have 100% sensitivity and 92.3% specificity. After completion of the questionnaire, the existence of any flaws reported in the questionnaire was evaluated by two independent investigators using a severity scale ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = non-existent defect, 2 = slight defect, 3 = defect recognizable from conversational distance, 4 = moderately severe defect and 5 = severe defect.) patients who scored ≥3 were excluded from the study.

The results were statistically analysed. Differences between the groups were investigated by Chi-square analysis for categorical variables, and Fisher exact test wherever required.

RESULTS

A total of 245 consecutive patients were enrolled in the study. Forty-five patients (18.36%) refused to participate in the study, and 23 patients had an objective assessment of >or = 3 on the Likert's scale and hence were excluded from the study. The remaining 177 patients constituted the final sample.

Of the 177 patients, 43 patients (24%) had the presence of pre-occupation and out of these eight patients (4.5%) were screened to be positive for BDD. The rate of BDD in patients presenting with cosmetic complaints was 7.5% and in those with general dermatology, complaints were 2.1%, with no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.156).

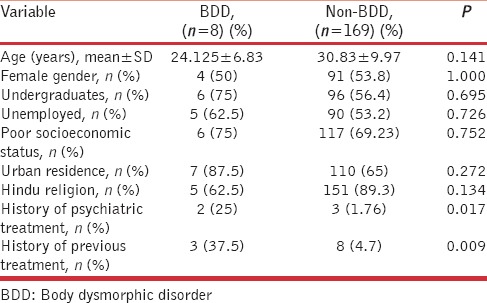

The summary of the demographic details of the BDD positive group and the BDD negative group are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients according to presence or absence of body dysmorphic disorder

The patients in the BDD group were younger (24.125 ± 6.83) than the patients in the non-BDD group (30.83 ± 9.97) but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.141). There was a female predominance in the non-BDD group, and there was an equal number of males and females in the BDD group. Majority of the patients had undergraduate qualifications in the non-BDD (56.4%) and BDD (75%) groups. There was no statistical association between gender (P = 1.000) and education (P = 0.695) with BDD in this study.

A significant association was seen with the history of seeking treatment for psychiatric complaints in the BDD group compared to the non-BDD group (25% vs. 1.76%; P = 0.017). None of the patients reported a history of suicidal attempt; however, one of the patients in the BDD group stated that she had harboured suicidal ideation. 4.7% (n = 8) in the non-BDD group gave a history of seeking treatment for their cosmetic complaints whereas it was significantly higher (P = 0.009) in the BDD group (37.5%, n = 3). All the three patients in the BDD group reported dissatisfaction with their previous treatments while only three of the eight non-BDD patients were dissatisfied.

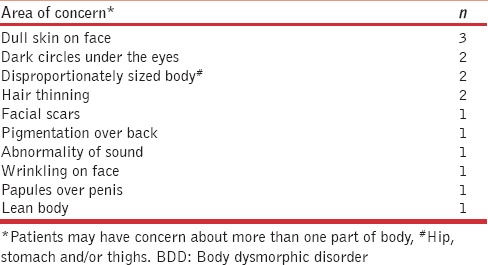

The details of the concern expressed by the patients are given in Table 2. Five patients (62.5%) reported more than one area of concern.

Table 2.

Areas of concern in the body in eight patients screened positive for body dysmorphic disorder

An inhibition to meet people and a fear of comments was observed in all patients. Other effects reported were refusing to work in dusty surroundings, avoiding marriage, effect on studies and wearing particular clothing.

DISCUSSION

In 1886, Morselli first coined the term dysmorphophobia and described patients who were obsessed about their ugliness.[10] The dermatologic literature contains many descriptions of patients with BDD, often under rubrics as dysmorphophobia, dysmorphic syndrome and monosymptomatic hypochondriasis.[5]

To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the prevalence of BDD in the Indian population. In India, the last 20–30 years have witnessed a tremendous growth in the surgical component of dermatology and dermatologists have widely adopted various surgical and cosmetic procedures.[11] Thus, it has become more important to identify patients with BDD.

Koran et al.[7] reported a point prevalence of 2.4% of BDD among the US adult population while in the German population it was 1.8%.[6] The frequency of BDD in dermatology outpatients ranges from 6.3–11.9%[1,2] to 8.6–29.4%[12,13,14] in patients seeking cosmetic treatment in previous studies. We report a comparable but lower rate of 4.5% in this study. Social and cultural factors, as well as the exposure to media, have been reported to influence body image and appearance satisfaction.[15,16] The sociocultural characteristics of the Indian population and a varied exposure to media might be responsible for the difference. Further studies need to be done to confirm the lower rates and identify the factors responsible.

BDD usually begins in adolescence[17] and the disorder appears to be chronic, and the establishment of an accurate diagnosis may take several years. Although considered to be more frequent in women, sex differences were not significant in some samples.[12,13] The results from our study appear to be in agreement with previous studies regarding age and gender.

Dunai et al.[18] reported that though BDD patients have executive function deficits, there was no difference in the number of years of education. There was no significant difference in the number of years of education in this study.

Facial flaws have been reported to be the most common focus in BDD,[19,20] but any part of the body can be of concern. In this study, 5 (62.5%) patients stated concerns regarding the face which included dullness of the skin, wrinkling, facial scars and dark circles under the eyes. Conrado et al.[13] reported dyschromia as the most frequent dermatological concern, it is interesting to note that 2 (25%) of our patients were concerned about dark circles under the eyes.

Body asymmetry was the most frequent concern noted by Dogruk Kacar et al.;[12] 2 (25%) of our patients also reported concerns about disproportionately sized body. Phillips and Diaz[4] noted that men were more likely to obsess about their genitals and body build.

Muscle dysmorphia, a pre-occupation that one's body is too small, ‘puny’ and inadequately muscular is a relatively recently recognised form of BDD that occurs almost exclusively in men.[21] In this study, we had one male patient with concerns about ‘papules on penis’ and another with concern about a ‘lean body’.

An unusual finding in our study was that of a patient with a concern about an abnormality of her voice which has not been reported previously.

Patients with BDD often have comorbidity with psychiatric disorders such as depression, social phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder.[22] A significant association with seeking treatment for psychiatric complaints was seen in our patients, but the records were not available.

BDD patients repeatedly seek treatments to find solutions for their defects and majority are dissatisfied with their results and consultations.[23] All the BDD patients in this study who had sought previous treatments expressed dissatisfaction.

The distress caused by BDD in the social and professional spheres of life may be extreme in some individuals.[23] One of our patients avoided marriage, and another patient refused to work in dusty surroundings limiting his job opportunities.

The major limitation of this study was the use of BDD questionnaire in the regional language (Hindi). The questionnaire has been validated in the dermatology setting but not in the Hindi version. The establishment of validity and reliability in the Hindi version would maximise the accuracy. A non-response bias was also possible, as the patients who refused to participate in the study might have caused underestimation of the prevalence of BDD, as patients with BDD may be more likely to refuse to participate. Despite these limitations, this is the first study for the screening for BDD in the Indian population, and further studies are needed to evaluate if there is a significantly lower prevalence in the Indian population compared to the Western population and to assess the sociocultural and media factors which might influence the same.

CONCLUSION

Awareness of the manifestations of BDD is important especially for cosmetic dermatologists who are more likely to encounter such patients. BDD is primarily a psychiatric disorder and thus requires a multidisciplinary approach to its treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Phillips KA, Crino RD. Body dysmorphic disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2001;14:113–8. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mackley CL. Body dysmorphic disorder. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:553–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2005.31160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips KA, Menard W. Suicidality in body dysmorphic disorder: A prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1280–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.7.1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips KA, Diaz SF. Gender differences in body dysmorphic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1997;185:570–7. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199709000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips KA, Dufresne RG. Body dysmorphic disorder. A guide for dermatologists and cosmetic surgeons. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2000;1:235–43. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200001040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buhlmann U, Glaesmer H, Mewes R, Fama JM, Wilhelm S, Brähler E, et al. Updates on the prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder: A population-based survey. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koran LM, Abujaoude E, Large MD, Serpe RT. The prevalence of body dysmorphic disorder in the United States adult population. CNS Spectr. 2008;13:316–22. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900016436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phillips KA, Stein DJ. Handbook on Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders. 1st ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015. pp. 59–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dufresne RG, Phillips KA, Vittorio CC, Wilkel CS. A screening questionnaire for body dysmorphic disorder in a cosmetic dermatologic surgery practice. Dermatol Surg. 2001;27:457–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2001.00190.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morselli E. Sulla dismorfofobia e sulla tafefobia: due forme non per anco descritte di Pazzia con idee fisse. Boll R Accad Genova. 1891;6:110–9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dogra S. Fate of medical dermatology in the era of cosmetic dermatology and dermatosurgery. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:4–7. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dogruk Kacar S, Ozuguz P, Bagcioglu E, Coskun KS, Uzel Tas H, Polat S, et al. The frequency of body dysmorphic disorder in dermatology and cosmetic dermatology clinics: A study from Turkey. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2014;39:433–8. doi: 10.1111/ced.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conrado LA, Hounie AG, Diniz JB, Fossaluza V, Torres AR, Miguel EC, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder among dermatologic patients: Prevalence and clinical features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hsu C, Ali Juma H, Goh CL. Prevalence of body dysmorphic features in patients undergoing cosmetic procedures at the National Skin Centre, Singapore. Dermatology. 2009;219:295–8. doi: 10.1159/000228329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veale DM, Lambrou C. The importance of aesthetics in body dysmorphic disorder. CNS Spectr. 2002;7:429–31. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900017922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markey CN, Markey PM. A correlational and experimental examination of reality television viewing and interest in cosmetic surgery. Body Image. 2010;7:165–71. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C, Weisberg R. Demographic characteristics, phenomenology, comorbidity, and family history in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:317–25. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunai J, Labuschagne I, Castle DJ, Kyrios M, Rossell SL. Executive function in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1541–8. doi: 10.1017/S003329170999198X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen A, Hollander E. Body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2000;23:617–28. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips KA, McElroy SL, Keck PE, Jr, Pope HG, Jr, Hudson JI. Body dysmorphic disorder: 30 cases of imagined ugliness. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:302–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope HG, Phillips KA, Olivardia R. The Adonis Complex: The Secret Crisis of Male Body Obsession. New York: Free Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veale D. Body dysmorphic disorder. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:67–71. doi: 10.1136/pmj.2003.015289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crerand CE, Franklin ME, Sarwer DB. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:167e–80e. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000242500.28431.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]