Sir,

Laryngeal or upper airway mucosal oedema is a common cause of airway obstruction after extubation and is thought to arise from direct mechanical trauma to the larynx by the endotracheal tube (ETT) or due to prolonged surgery.[1,2]

Upper airway oedema predisposes the patient to post-operative airway obstruction. It presents mostly as post-extubation stridor and at times warrants post-operative elective ventilation. The treatment involves parenteral administration of corticosteroids, epinephrine nebulisation and inhalation of a helium and oxygen mixture.

Nebulised epinephrine acts on α-adrenergic receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells, causing vasoconstriction and decreased blood flow, which diminishes oedema.[3] The presence of an ETT in the larynx limits laryngeal exposure to nebulised epinephrine. The limitation of nebulising through the ETT is that the mist is delivered only to the lower airways and upper airway is spared. Common practice is to attach a small volume Hudson nebuliser to the venturi mask after extubation with the patient propped up. However, Hudson nebuliser needs to be placed vertically for effective nebulisation and this is feasible only when the patient is in upright sitting posture which is not always possible in the immediate post-operative period. This limits effective nebulisation of the upper airway, and patients develop stridor on extubation even requiring intubation.

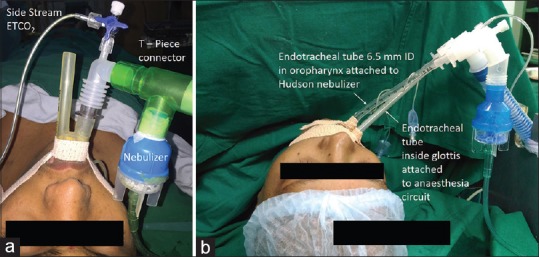

A better option would be to reduce upper airway oedema before extubation. In patients without difficult airway except for risk of laryngeal oedema during extubation such as foreign body bronchus or microlaryngeal surgery, the tube can be replaced with laryngeal mask airway (LMA) while the patient is still anaesthetised (Bailey's Manoeuvre) and a T-piece connector is attached to the LMA for connecting a low volume gas driven nebuliser. LMA will ensure that nebulised epinephrine is directed and deposited in and around the laryngeal structures [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) Nebulisation through ProSeal laryngeal mask airway (b) nebulisation through an endotracheal tube in the oropharynx

In patients with difficult airway where extubation has to be done once patient is fully awake and obeying commands, epinephrine can still be nebulised to the upper airway by passing an ETT of 8 mm internal diameter (ID) in the oral cavity, with the tube's bevel positioned just above the glottis using video or direct laryngoscope. This ETT is secured by the side of the ETT already in place [Figure 1b]. A larger diameter ETT (8 mm ID) with shortened length at an oxygen flow rate of 8–10 L/minute is required to ensure successful delivery of the nebulised drug. Upper airway oedema involves structures such as arytenoids, epiglottis and vocal folds, the nebulised drug easily reaches them as they are in proximity to the bevel of ETT. One milligram epinephrine in 5 ml normal saline has proved successful for upper airway obstruction in adults.[4] Minor drawbacks include delay in extubation time by 10–15 minutes and accommodating another tube inside the pharynx. Though laryngeal oedema is mostly transient and self-limiting, clinically significant post-extubation laryngeal oedema occurs in up to 30% patients, with 4% needing reintubation.[3] We conclude that it is better to treat upper airway oedema before extubation with these techniques and reduce the risk of stridor and need for reintubation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Colice GL, Stukel TA, Dain B. Laryngeal complications of prolonged intubation. Chest. 1989;96:877–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastanos N, Estopá Miró R, Marín Perez A, Xaubet Mir A, Agustí-Vidal A. Laryngotracheal injury due to endotracheal intubation: Incidence, evolution, and predisposing factors. A prospective long-term study. Crit Care Med. 1983;11:362–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198305000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wittekamp BH, van Mook WN, Tjan DH, Zwaveling JH, Bergmans DC. Clinical review: Post-extubation laryngeal edema and extubation failure in critically ill adult patients. Crit Care. 2009;13:233. doi: 10.1186/cc8142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MacDonnell SP, Timmins AC, Watson JD. Adrenaline administered via a nebulizer in adult patients with upper airway obstruction. Anaesthesia. 1995;50:35–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]