Abstract

In the context of a preexisting resource inequality, the concerns for strict equality (allocating the same number of resources to all recipients) conflict with the concerns for equity (allocating resources to rectify the inequality). The present study demonstrated age related changes in children’s (3- to 8-years-old, N = 133) ability to simultaneously weigh the concerns for equality and equity through the analysis of children’s judgments, allocations, and reasoning in the context of a preexisting inequality. Three- to 4-year-olds took equity into account in their judgments of allocations, but allocated resources equally in a behavioral task. In contrast, 5- to 6-year-olds rectified the inequality in their allocations, but judged both equitable and equal allocations to be fair. It was not until 7- to 8-years-old that children focused on rectifying the inequality in their allocations and judgments, as well as judged equal allocations less positively than equitable allocations, thereby demonstrating a more complete understanding of the necessity of rectifying inequalities. The novel findings revealed age related changes from 3- to 8-years-old regarding how the concerns for equity and equality develop, and how children’s judgments, allocations, and reasoning are coordinated when making allocation decisions.

Keywords: Moral development, fairness, equity, inequality, equality

Decisions regarding the fair allocation of resources pervade social life, from disputes over toys in childhood, to resolving longstanding, societal inequalities in adulthood; access to resources is a fundamental human concern. Resource allocation has been studied by psychologists, behavioral economists, and philosophers (Fehr, Bernhard, & Rockenbach, 2008; Killen & Smetana, 2015; Sen, 2009). The interdisciplinary focus reveals the complexity of the topic, with research investigating what constitutes a legitimate claim, how to balance the needs of the individual and the group, and concepts of fairness and justice (Blake & McAuliffe, 2011; Cooley & Killen, 2015; Paulus & Moore, 2014; Schmidt, Rakcozy, & Tomasello, 2012; Turiel, 2008, 2014).

Research in developmental science has shown that young children are highly sensitive to concerns about equality, and divide resources according to strict equality – allocating the same number of resources to all recipients – in many contexts. By 3-years-old, children allocate resources equally between family members, friends, and strangers (Kenward & Dahl, 2011; Olson & Spelke, 2008), judge equal allocations to be fair, and reason about the concerns for equality (Cooley & Killen, 2015). By 6-years-old, children will even throw resources away rather than allocate them unequally (Blake & McAuliffe, 2011; Shaw & Olson, 2012). The aversion to unequal allocations has been documented cross culturally (Blake et al., 2015, but see Paulus, 2015). There are contexts, however, in which equal allocations may not be fair. Contexts with equity-based concerns (e.g., merit, need, preexisting inequalities), for example, may necessitate unequal allocations to ensure fairness.

In the context of a preexisting inequality – when one recipient has received fewer resources than another – a strictly equal allocation perpetuates the status quo inequality between recipients. To rectify the inequality, resources have to be divided unequally, with more going to the recipient who previously had less. Given children’s documented concern for strict equality throughout much of childhood, it may not be until later in development that children begin to allocate resources unequally to rectify a preexisting inequality.

In one study, 3.5- to 7.5- and 7.5- to 11.5-year-olds were presented with group-level inequalities based on race and were asked to allocate resources (e.g., cookies) to members of each of these groups (Olson, Dweck, Spelke, & Banaji, 2011). In this context, 3.5- to 7.5-year-olds perpetuated the race-based inequality. It was not until 7.5- to 11.5-years-old that children rectified the inequality. Yet, in a related study, when children were shown inequalities of necessary resources (e.g., medicine), 5- to 6-year-olds rectified the inequality (Elenbaas & Killen, 2016; also see Li, Spitzer, & Olson, 2014, Paulus, 2014). Thus, past research on children’s responses to inequalities is mixed.

Further, it remains unknown how children’s understandings of the normative, prescriptive concern for equity-based fairness develop cognitively and behaviorally, and how these modalities relate to one another. That is, it is unclear whether children in past research allocated equitably because they were unable to allocate equally, personally preferred the recipient with less, or out of the concern for rectifying an inequality due to the harm to the disadvantaged recipient. A comprehensive assessment of how children evaluate equal, equitable, and unequitable allocations, is needed to understand children’s understanding of the normative, prescriptive concern for equity.

Theoretical Framework

The theoretical perspective guiding the current study stems from moral development and social cognition, referred to as social domain theory (Turiel, 1983, 2008). Social domain theory has argued that many social contexts are multifaceted, involving multiple relevant concerns. In the context of preexisting inequalities, children may think about the equality (ensuring that all involved parties receive the same share) or equity (ensuring that individuals who were disadvantaged in the past are fairly compensated). Each of these concerns is constructed throughout development, and informs children’s allocation decisions differently in different contexts.

Social domain theory has shown that judgments, behavior, and reasoning represent distinct, yet increasingly coordinated processes throughout development (Turiel, 2008). In resource allocation contexts, allocation assessments provide information regarding which concern children appear to give priority to (e.g., equality or equity). Judgment assessments provide necessary information regarding children’s developing understanding of each of the multiple relevant concerns (e.g., equity, equality). Additionally, reasoning assessments allow for an assessment of children’s underlying motivations for their allocations, and can provide converging evidence that children’s judgments of multiple concerns influences how they decide how to allocate resources.

The present study investigated children’s developing ability to evaluate resource allocation decisions across judgments, behavior, and reasoning for different moral concerns (i.e. equity, equality). Social domain theory postulates that children construct knowledge through their interactions and inferences, which informs their judgments and reasoning (Killen & Rutland, 2011; Turiel, 1983). From this approach, coordination refers to the process of how judgments and reasoning are integrated into a child’s decisions and the extent to which each modality reflects the same set of moral considerations. Research to date has not conducted analyses that compare children’s allocations, judgments of allocations, and their reasoning for their allocations. This was a central and novel goal of the present study.

In many resource allocation contexts, multiple moral concerns may conflict (e.g., equality and equity). In these situations, children may recognize that both equality and equity are important– by judging them both to be fair means of allocation – but nonetheless must give priority to one of these concerns when allocating. As children construct a more advanced understanding of equity, they may come to see strict-equality as an unfair allocation practice in the context of inequalities. A mature understanding of equity involves not only allocating resources equitably, but also recognizing that a strictly equal allocation would be unfair and why it would be unfair. Documenting the developing coordination of children’s early moral judgments and reasoning with their allocations is critical to understanding the broader picture of moral development (Dunn, 2006; Killen & Smetana, 2015).

Present Experiment

The present experiment investigated age related changes in children’s developing allocations, judgments, and reasoning in a context of inequality. Three age groups (Younger: 3- to 4-years-old; Middle: 5- to 6-years-old; Older: 7- to 8-years-old) were assessed. No study to our knowledge has examined age-related changes from 3- to 8-years-old for children’s judgments, reasoning, and allocation responses regarding three distinct allocation contexts, equality, equity, and inequity, when a pre-existing inequality regarding resources was made explicit and salient.

Children were presented with a vignette about two recipients, one from a wealthy town with a lot of resources and another from a poor town with no resources. To control for perceptions of merit in the present study, children were explicitly told that both recipients worked, and produced, the same amount. Children were asked to make decisions about their allocation, reasoning, and judgments of equal (the same to both recipients), equitable (more to the recipient with no resources), and unequitable (more to the recipient with an excess of resources) allocations.

It was hypothesized that: 1) The younger age group will demonstrate an emerging understanding of equity in their judgments and reasoning, but a preference for strict equality when allocating and judging equal allocations. Based on research demonstrating 3-to 4-year-old children’s proclivity for equal allocations (Cooley & Killen, 2015; Olson & Spelke, 2008), we hypothesized that these children would allocate resources equally in the present study and judge equal allocations to be fair. Further, based on research demonstrating that children’s concern for equity develops early, specifically when equal allocations are not possible (Li, Spitzer, & Olson, 2015), we hypothesized that the emerging concern for equity would lead 3- to 4-year-old children to judge equitable allocations to be more fair than unequitable allocations.

2) The middle age group would demonstrate an emerging preference for equity over strict equality, but would still maintain the concern for strict equality. Based on research finding that 5-, but not 3-year-old children share more with poor than rich individuals (Paulus, 2014), we hypothesized that 5- to 6-year-olds would allocate resources equitably, and judge equitable allocations to be fair. Further, based on research finding that 5- to 6-year-old children evaluate equal allocations positively (Cooley & Killen, 2015), we hypothesized that 5- to 6-year-old children would also judge equal allocations to be fair.

3) The older age group would demonstrate an increasing concern for equity, and would begin to recognize the obligation to rectify unjustified inequalities by no longer judging equal allocations to be fair. Based on research finding that 7- to 8-year-old children act to rectify inequalities (Blake et al., 2015; Fehr, Bernhard, & Rockenbach, 2008), we hypothesized that 7- to 8-year-old children would allocate equitably and judge equitable allocations to be fair. Further, research has documented that children become more rigid in their conceptions of fairness during this period, reporting that only one allocation is fair, and deviations from that allocation are unfair (Damon, 1977; Sigelman & Waitzman, 1991). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that 7- to 8-year-old children would not judge equal allocations to be fair

Further, based on theoretical and empirical accounts documenting the interrelation between children’s judgments, behaviors, and reasoning (Killen & Rutland, 2011; Turiel, 2008), we had two additional hypotheses regarding the interrelation between children’s judgments, allocations, and reasoning for their allocations. It was hypothesized that 4) children who allocated equitably would reference the concern for rectifying the inequality, whereas children who allocated equally would reference the concern for equality; and 5) children’s allocations would be predicted by their judgments of equal and equitable allocations.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 3- to 8-year-old children (N = 133), divided into three age groups: Younger (3- to 4-years; n = 55, 29 females; M = 4.30, range: 3.22–4.99), Middle (5- to 6-years; n = 53, 19 females; M = 5.76, range: 5.01–6.84), and Older (7- to 8-years; n = 25, 11 females; M = 7.82, range: 7.12–8.99). Participants were from schools serving low- to middle-income families in the Mid-Atlantic region of the U.S. All children in the age range were invited to participate. Differences in sample sizes between groups reflected enrollment at the participating schools. Written parental consent and children’s verbal assent were obtained for all participants. Participant race/ethnicity reflected the U.S. distribution with 70% ethnic majority (European-American) and 30% ethnic minority (Latino, Asian-American, African-American, Other).

Procedure

Research assistants interviewed participants in the participant’s school. Cardboard cutouts of characters and resources were used to illustrate the stories and allowed children to allocate resources. Children were first trained on how to use the Likert-type scale (see Supplementary Materials for the training script). Story characters were present throughout the experiment, and resources were given to children during resource allocation questions, and were aligned underneath the characters during judgment questions. Interviews took approximately 20 minutes to complete.

Participants heard vignettes about two characters, Nug and Thump, who worked to acquire resources (“blickets”) (as with previous research with children, novel characters and resources have the advantage of serving as a control across participants in terms of recipient demographics). The recipients were introduced as being from fictional towns that have either a history of having or not having resources, providing a reason for the inequality beyond the control of the recipients. One recipient was described as having a lot of resources and being from a town with many resources, whereas the other recipient was described as having no resources and being from a town with few resources. Pilot testing yielded no order effects between the tasks, thus, assessments were administered in a fixed order: Resource Allocation, Judgments of Allocations.

The merit of the two characters was controlled for given research on young children’s understanding of merit (Baumard, Mascaro, & Chevallier, 2012). Participants were explicitly told that both recipients worked the same and found the same amount.

Manipulation check

Participants were asked two memory questions: (1) To identify which character had a lot of resources and which character had none. (2) To identify if one character worked harder, or if both characters worked the same amount. If a participant failed a question, the vignette was repeated up to two additional times and both memory questions were reassessed. Less than 10% of participants failed either memory question. All participants ultimately answered both memory questions correctly, thus, none were excluded from the sample.

Resource Allocation

Participants completed two assessments: 1) Resource Allocation and 2) Reasoning for Resource Allocation. In the Resource Allocation assessment, participants were asked, “Can you show me how many blickets you think Nug and Thump should each get?” Participants were given six resources to allocate between the recipients. All participants allocated all six resources. The number of resources allocated to the recipient with no resources was recorded on a scale from 0 to 6.

In the Reasoning for Resource Allocation assessment, participants were asked, “Why do you think Nug should get [X] and Thump should get [Y]?” Participants gave their answer verbally while the research assistant recorded it for content coding. Reasons were coded for quantitative analyses into four categories drawn from past research (Damon, 1977; Sigelman & Waitzman, 1991): 1) Others’ Welfare (references to the welfare of the characters; e.g., “They’ll be sad”), 2) Strict Equality (references to the equal treatment of individuals; e.g., “they should get the same amount”), 3) Rectifying Inequality (references to the inequality between the characters; e.g., “she doesn’t have any and she has a lot”), and 4) Other (statements that contradict the story and other undifferentiated or global statements). Reasoning was coded as 1 = full use of the category; .5 = partial use; 0 = no use and analyses were conducted on proportional usage. Less than 5% of the participants used more than one code. Two research assistants, blind to the hypotheses of the study, conducted the coding. On the basis of 25% of the interviews (n = 34), Cohen’s κ = .84 for inter-rater reliability.

Judgments of Allocations

The Judgments of Allocations task consisted of three assessments: 1) Judgment of Equal Allocation, 2) Judgment of Equitable Allocation, and 3) Judgment of Unequitable Allocation. In the Judgment of Equal Allocation assessment, participants were asked about another, hypothetical, gender-matched, child’s decision to allocate three resources to each recipient (“How Okay or not Okay is it for Sam to give Nug and Thump the same amount?”). Participants then indicated their evaluation on a Likert-type scale (1 = really not OK, 6 = really OK) by either pointing or saying their response aloud. This same format was used for the Judgment of Equitable Allocation (five to the recipient with no resources and one resource to the recipient with a lot of resources) and Judgment of Unequitable Allocation (one resource to the recipient with no resources and five resources to the recipient with a lot of resources) assessments.

Resource Type

Given that some research has found differences in children’s allocations based on the resource being allocated (Chernyak & Sobel, 2015; Shaw & Olson, 2013), while other research has not (Warneken et al., 2011), we conducted analyses to determine if children would differ in their allocations of luxury and necessary resources in an inequality-based context. Half of the participants were told that the resources, blickets, were luxury resources (enjoyable to have, but not needed to avoid harm) and the other half were told that they were necessary resources (needed to avoid harm).

Data Analytic Plan

Analyses testing hypotheses regarding differences by age group were conducted using Univariate ANOVAs. Analyses testing hypotheses regarding reasoning and the interrelation between allocations, judgments, and reasoning, were conducted as repeated measures ANOVAs. The use of repeated measures ANOVAs for reasoning data is a widely used approach (for a review see, Wainryb, Shaw, Laupa, & Smith, 2001). ANOVAs were used over other statistical approaches (e.g., regression-based analyses) to allow for the assessment of the interrelations between children’s allocations, judgments, and reasoning for each age group. This data analytic approach enabled the documentation of the developing patterns of interrelations across and within age groups. To interpret effects, post-hoc, independent-samples t-tests with Bonferroni adjustments were conducted. Preliminary analyses revealed no significant differences for gender or resource type, thus, gender and resource type were excluded from further analyses.

Results

Resource Allocation Task

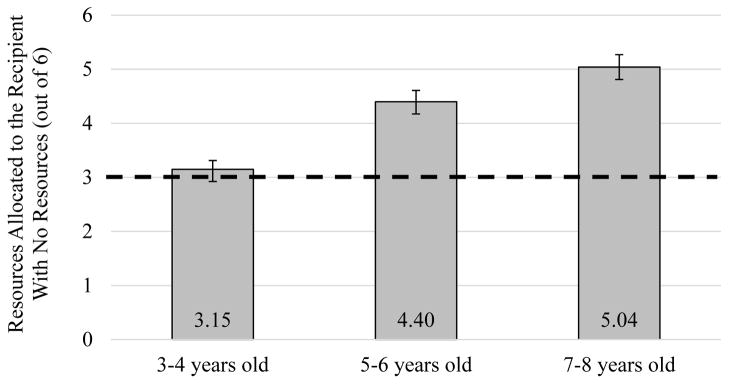

To test the hypothesis that children would allocate resources more equitably with age, a univariate ANOVA by Age Group (3–4 years, 5–6 years, 7–8 years) was conducted (see Figure 1). Consistent with our hypotheses, a main effect for age was found (F(2,130) = 21.30, p < .001, ηp2 = .25); with age, children allocated more resources to the recipient with no resources. The older age group (M = 5.04, SD = 1.14) and the middle age group (M = 4.40, SD = 1.52) allocated more resources to the recipient with no resources than did the younger age group (M = 3.15, SD = 1.21), ps < .001. No difference was found between the older and middle age groups (p = .15).

Figure 1.

Mean number of resources allocated to the recipient with no resources (out of 6). p values reported in text. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each column.

One-sample t-tests were conducted for each age group to test hypotheses regarding when children would begin to deviate from an equal allocation (3 resources to each recipient). Consistent with our hypotheses, 5- to 6-year-olds (t(52) = 6.67, p < .001, d = 0.92) and 7- to 8-year-olds (t(24) = 8.98, p < .001, d = 1.79), but not 3- to 4-year-olds (t(54) = 0.89, p = .38, d = 0.12), allocated significantly different from equal, giving more to the recipient with no resources.

Reasoning for Resource Allocation

The proportion of use for each form of reasoning used by children in explaining their resource allocation were Strict Equality (M = .24), Rectifying Inequalities (M = .43), and Others’ Welfare (M = .14).

To test the hypothesis that children would use different reasoning to justify their allocations based on how they allocated resources a 3 (Age Group: 3–4 years, 5–6 years, 7–8 years) X 3 (Allocation: Equal, Equitable, Unequitable) X 3 (Reasoning: Strict Equality, Rectifying Inequalities, Others’ Welfare) ANOVA with repeated measures on the last factor was conducted (see Table 1). Consistent with our hypotheses, a main effect for Reasoning was found (F(2,250) = 11.51, p < .001, ηp2 = .08), which was explained by an Allocation by Reasoning interaction (F(4,250) = 43.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .41). Children who allocated resources Equitably were more likely to reference the concern for rectifying the inequality than were children who allocated Equally (p = .006) and Unequitably (p < .001). Further, children who allocated resources Equally were more likely to reference the concern for equality than were children who allocated Equitably and Unequitably (ps < .001). No differences were found for references to others’ welfare (ps > .95) No effect for Age was found (p = .17).

Table 1.

Means (and Standard Deviations) for Reasoning by Children’s Allocations

| Strict Equality | Rectifying Inequality | Others’ Welfare | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant’s Allocation | n | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| Equitable Allocation | 65 | .02 | (.14) | .82 | (.35) | .08 | (.22) |

| Equal Allocation | 55 | .55 | (.50) | .00 | (.00) | .23 | (.42) |

| Unequitable Allocation | 13 | .00 | (.00) | .35 | (.47) | .04 | (.14) |

p values reported in text.

Judgments of Equitable, Equal, and Unequitable Allocations

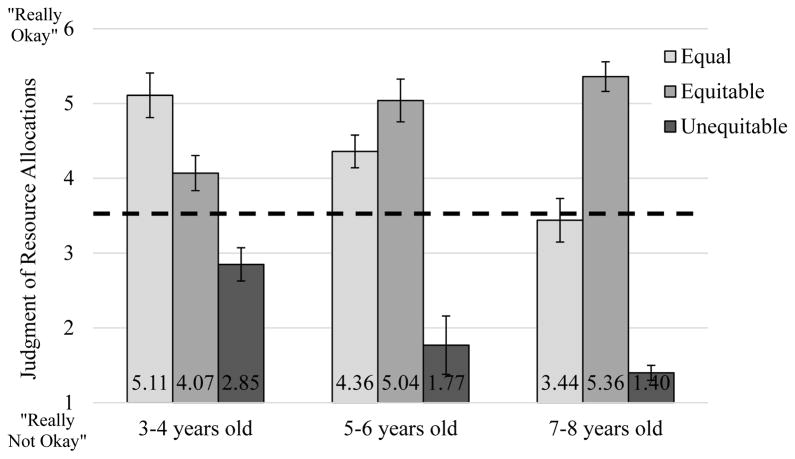

To test the age-related hypotheses for children’s judgments of equitable, equal, and unequitable allocations, a 3 (Age Group: 3–4 years, 5–6 years, 7–8 years) X 3 (Allocation: Equitable, Equal, Unequitable) ANOVA with repeated measures on the last factor was conducted (see Figure 2). To test hypotheses regarding whether children would judge specific allocations to be “OK” or “not OK”, one-sample t-tests were conducted for each age group on children’s judgments of equitable, equal, and unequitable allocations (range: 1–6) against a neutral evaluation (3.5).

Figure 2.

Mean judgment of equal, equitable, and unequitable allocations by age. 6 = “Really Okay”, 1 = “Really Not Okay”. p values reported in text. Standard errors are represented in the figure by the error bars attached to each column.

Consistent with our hypotheses regarding children’s judgments of allocations, a significant effect for Allocation was found (F(2,260) = 79.77, p < .001, ηp2= .38), which was explained by an interaction between Age Group and Allocation (F(4,260) = 8.89, p < .001, ηp2 = .12). First, age-related results are presented to allow for a developmental account of the judgments of the allocations. Then, results describing the patterns of judgments, within each age group, are presented to allow for an analysis regarding the developing coordination between judgments.

Equitable allocations

Children judged equitable allocations more positively with age. Children in the older (M = 5.36; SD = 1.11, p = .01) and middle age groups (M = 5.04; SD = 1.71, p = .02) judged equitable allocations more positively than did children in the younger age group (M = 4.07; SD = 2.21). No difference was found between the older and middle age groups (p = .99). Further, the middle (t(52) = 6.55, p < .001, d = 0.90) and older (t(24) = 8.35, p < .001, d = 1.67) age groups judged equitable allocations significantly different from neutral, judging them to be “OK”. The younger age group’s judgments, however, were only marginally different from a neutral judgment (t(54) = 1.92, p = .06, d = 0.26). That is, while 5- to 6-year-olds and 7- to 8-year-olds judged equitable allocations to be “OK”, 3- to 4-year-olds did not significantly judge equitable allocations to be fair.

Equal allocations

Children judged equal allocations less positively with age. Children in the younger age group (M = 5.11, SD = 1.62) judged an equal allocation more positively than did children in the older age group (M = 3.44, SD = 1.94; p = .001). Significant differences were not found, however, between the middle (M = 4.36, SD = 2.08) and the younger (p = .12) or older (p = .14) age groups. Further, the younger (t(54) = 7.38, p < .001, d = 0.99) and middle (t(52) = 4.36, p = .004, d = 0.41) age groups judged equal allocations significantly different from neutral, judging them to be “OK”. The older age group’s judgments, however, did not differ from a neutral judgment (t(24) = −.155, p = .88, d = 0.03). That is, while 3- to 4-year-olds and 5- to 6-year-olds judged equal allocations to be “OK”, 7- to 8-year-olds did not judge equal allocations to be fair.

Unequitable allocations

Children judged the unequitable allocation less positively with age. Children in the in the middle (M = 1.77, SD = 1.44; p = .003) and older (M = 1.40, SD = .50; p = .001) age groups judged an unequitable allocation to be less fair than did children in the younger age group (M = 2.85, SD = 2.16). Significant differences were not found between the middle and the older age groups (p = .99). However, the younger (t(54) = 2.22, p = .031, d = .30), middle (t(52) = 8.75, p < .001, d = 1.20), and older (t(24) = 21.00, p < .001, d = 4.20) age groups all judged unequitable allocations significantly different from neutral, judging them to be “not OK”.

Patterns of judgments of equitable, equal, and unequitable allocations

Children in the younger age group judged equal allocations more positively than equitable (p = .015) and unequitable (p < .001) allocations, and judged equitable allocations more positively than unequitable (p = .002) allocations. Children in the middle age group did not differ in their judgments of equal and equitable allocations (p = .20), and judged both equal and equitable allocations more positively than unequitable allocations (ps < .001). Finally, children in the older age group judged equitable allocations more positively than equal (p = .001) and unequitable (p < .001) allocations, and judged equal allocations more positively than unequitable (p < .001) allocations.

Relation Between Judgment and Allocation

To test hypotheses regarding the relation between children’s judgments of allocations and their actual allocations, participants were grouped on their patterns of judgments of allocations. Three major patterns of judgments emerged: 1) Children who judged equitable allocations to be more fair than equal and unequitable allocations (Equitable; n = 46), 2) children who judged equal allocations to be more fair than equitable and unequitable allocations (Equal; n = 30), and 3) children who judged both equitable and equal allocations to be more positive than unequitable allocations, but provided the same judgment score for equitable and equal allocations (Same Judgment; n = 36). Less than 10% of participants evidenced any other pattern of judgments of allocations, thus, alternative patterns of judgments were dropped from analyses.

A 3 (Age Group: 3–4 years, 5–6 years, 7–8 years) X 3 (Pattern of Judgments: Equitable, Equal, Same Judgment) ANOVA was conducted, and revealed a significant effect for Pattern of Judgments (F(2,103) = 10.98, p < .001, ηp2= .18). Children who judged the equitable allocation to be the most fair (M = 5.02, SD = 1.36; p < .001) and those who provided the same judgment for the allocations (M = 4.11, SD = 1.33; p =.027) allocated more resources to the recipient with no resources than did children who judged equal allocation to be the most fair (M = 3.27, SD = .828). No differences were found between children who judged equal to be the most fair and those who provided the same judgment for the allocations (p = .16). An Age Group by Pattern of Judgment interaction was not found (p = .57).

Discussion

The novel findings of this study were that children’s allocations, judgments, and reasoning developed from 3- to 8-years-old, evidencing a developing understanding of both equity and equality, as well as increased coordination of children’s allocations, judgments, and reasoning. Research on young children’s allocations in the context of preexisting inequalities has been mixed, with some studies finding that children will perpetuate an inequality (Olson et al., 2011) and others finding that children will rectify it (Elenbaas & Killen, in press; Li, et al., 2014; Paulus, 2014). Consistent with our hypotheses, the present results demonstrated that, while 3- to 4-year-old children recognized the concern for equity in their judgments, they still gave preference to strict-equality in their allocations. By 5- to 6-years-old, however, children rectified inequalities and judged equitable allocations to be fair. Finally, by 7- to 8-years-old, children prioritized the concern for equity in their allocations and judgments, and no longer judged equal allocations to be fair.

These results also support theoretical accounts of social and moral development arguing that children’s ability to simultaneously weigh multiple relevant concerns undergoes significant development during the childhood years (Damon, 1977; Turiel, 1983). Consistent with our hypotheses, children’s developing ability to simultaneously weigh the concerns for equality and equity was demonstrated in their judgments of allocations. Three- to 4-year-olds recognized the concern for equality, judging it to be fair, while simultaneously evidencing an emerging understanding of equity, differentiating it from an unequitable allocation. By 5- to 6-years-old, however, children demonstrated the simultaneous concern for both equity and equality, judging both means of allocations to be fair. Finally, with age, 7- to 8-year-olds recognized the conflict between equity and equality in their judgments, judging equal allocations less positively. Thus, children’s ability to simultaneously weigh the concerns for equality and equity undergoes significant development throughout the childhood years.

Further, the present study documented children’s ability to coordinate their judgments, reasoning, and allocations. Past research on this topic is mixed, with some researchers providing evidence for the coordination between judgment and behavior (Turiel, 2008), and others finding contexts in which discrepancies arise (Blake, McAuliffe, & Warneken, 2014). Regarding resource allocation, past studies using first-person resource allocation paradigms have documented that, while children will report that they should share equally with peers, they often take more for themselves (Smith, Blake, & Harris, 2013).

The present results support theoretical accounts for the interrelation between children’s moral judgments and their allocation behaviors in third-person contexts (Turiel, 2008). As children’s understanding of the moral concerns for equity and equality develop, their allocations, judgments, and reasoning regarding allocations were coordinated accordingly; children who were primarily concerned with rectifying the inequality judged equitable allocations to be the most fair, allocated equitably themselves, and explained their rationale for their allocations by referencing the need to rectify inequalities. Future studies examining the type of resource, whether it is necessary (medicine, school supplies) or a luxury (candy, stickers, stars), would provide new insights into the varied contexts when children rectify or perpetuate social inequalities (Elenbaas & Killen, in press; Rizzo, Elenbaas, Cooley, & Killen, in press).

Additionally, research has documented other cognitive and social-cognitive skills, (e.g., theory of mind) that may help explain the present findings. Mulvey, Buchheister, and McGrath (in press) argue that children’s developing theory of mind abilities enable them to better understand the mental states of individuals disadvantaged by inequality, thus helping them to recognize the harmful impact to the victims of inequality. Other research, however, has found negative relations between children’s theory of mind and their tendency to share (Cowell et al., 2015).

Foundational research has also found that proportional reasoning (Adams, 1965), and other forms of mathematical reasoning (Hook, 1978; Hook & Cook, 1979) can help account for the development of equity concerns. It is likely that multiple social and cognitive processes influence children’s conceptions of fairness simultaneously throughout development. Thus, future research should examine how children’s social-cognitive (theory of mind) capacities, along with their cognitive (numerical and mathematical) abilities, interact with their developing understanding of principles of fairness (e.g., equality, equity, and merit).

Based on past research documenting the early emerging concern for merit (Baumard, Mascaro, & Chevallier, 2011), the present study explicitly controlled for merit-based equity. It is possible that children were primed to think about the equal levels of merit between the characters, leading to increased instances of equal allocations and positive judgments of equal allocations. Future research should examine this possibility by manipulating the merit and need of the recipients involved in the inequality.

The current study assessed children’s resource allocations and judgments of allocations in a fixed order. While extensive pilot testing was conducted, yielding no order effects, it is important for future research to consider potential carry-over effects when assessing multiple measures of a specific construct. Further, a limitation of the present study was the relatively small sample size for the oldest age group. To ensure sufficient power for the patterns of judgments analyses, future studies should be conducted with a larger 7- to 8-year-old group to determine whether an age by judgment type interactions exist.

In summary, the present study demonstrated developmental patterns of children’s resource allocations, judgments of allocations, and reasoning regarding allocations in the context of a preexisting inequality. Across the three age groups, children’s concern for equity developed, while children recognized the unfairness of strict-equality in this context. By investigating children’s developing social-cognitive judgments and reasoning, in addition to their allocation behaviors, the present study provides an important insight into children’s conceptions of fairness, equity, and equality.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first author is supported by a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pre-doctoral Traineeship (#T32HD007542). We thank Shelby Cooley, Audun Dahl, Laura Elenbaas, Aline Hitti, Kelly Lynn Mulvey, and Jeeyoung Noh, for their invaluable contributions to the project. In addition, we thank the research assistants who helped with the data collection, coding, and analysis: Chelsea Burrell, Erica Choi, Rachel Croce, Kimberly Greenberg, Samantha Jay, Leon Li, Tara Moores, and Miranda Rosenberg. Importantly, we would like to thank the schools, students, and parents involved with this study.

References

- Baumard N, Mascaro O, Chevallier C. Preschoolers are able to take merit into account when distributing goods. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48:492–8. doi: 10.1037/a0026598. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0026598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K. “I had so much it didn’t seem fair”: Eight-year-olds reject two forms of inequity. Cognition. 2011;120:215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K, Warneken F. The developmental origins of fairness: The knowledge-behavior gap. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014;18:559–561. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.08.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake PR, McAuliffe K, Corbit J, Callaghan TC, Barry O, Bowie A, … Warneken F. The ontogeny of fairness in seven societies. Nature. 2015;528:258–261. doi: 10.1038/nature15703. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature15703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak N, Sobel DM. Equal but not always fair: Value-laden sharing in preschool-aged children. Social Development. 2015 http://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12136.

- Cooley S, Killen M. Children’s evaluations of resource allocation in the context of group norms. Developmental Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1037/a0038796. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0038796. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cowell JM, Sarnek A, List J, Decety J. The curious relation between theory of mind and sharing in preschool age children. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0117947. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W. The social world of the child. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Moral development in early childhood and social interaction in the family. In: Killen M, Smetana JG, editors. Handbook of moral development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 331–350. [Google Scholar]

- Elenbaas L, Killen M. Children rectify inequalities for disadvantaged groups. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/dev0000154. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fehr E, Bernhard H, Rockenbach B. Egalitarianism in young children. Nature. 2008;454:1079–83. doi: 10.1038/nature07155. http://doi.org/10.1038/nature07155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanngiesser P, Warneken F. Young children consider merit when sharing resources with others. PloS One. 2012;7:e43979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043979. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0043979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenward B, Dahl M. Preschoolers distribute scarce resources according to the moral valence of recipients’ previous actions. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47:1054–1064. doi: 10.1037/a0023869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Rutland A. Children and social exclusion: Morality, prejudice, and group identity. New York: Wiley/Blackwell Publishers; 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killen M, Smetana J. Origins and development of morality. In: Lamb ME, editor. Handbook of child psychology and developmental science. 7. III. NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015. pp. 701–749. [Google Scholar]

- Li V, Spitzer B, Olson KR. Preschoolers reduce inequality while favoring individuals with more. Child Development. 2014;85:1123–33. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12198. http://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGillicuddy-De Lisi AV, Daly M, Neal A. Children’s distributive justice judgments: Aversive racism in Euro-American children? Child Development. 2006;77:1063–1080. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Buchheister K, McGrath K. Evaluations of intergroup resource allocations: The role of theory of mind. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2015.10.002. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Dweck CS, Spelke ES, Banaji MR. Children’s responses to group-based inequalities: Perpetuation and rectification. Social Cognition. 2011;29:270–287. doi: 10.1521/soco.2011.29.3.270. http://doi.org/10.1521/soco.2011.29.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson KR, Spelke ES. Foundations of cooperation in young children. Cognition. 2008;108:222–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M. The early origins of human charity: Developmental changes in preschoolers’ sharing with poor and wealthy individuals. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014;5:344. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00344. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M. Children’s inequity aversion depends on culture: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2015;132:240–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.12.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus M, Moore C. The development of recipient-dependent sharing behavior and sharing expectations in preschool children. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50:914–921. doi: 10.1037/a0034169. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0034169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The moral judgment of the child. New York: Free Press; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo MT, Elenbaas L, Cooley S, Killen M. Children’s recognition of fairness and others’ welfare in a resource allocation task: Age related changes. Developmental Psychology. doi: 10.1037/dev0000134. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Rakoczy H, Tomasello M. Young children enforce social norms selectively depending on the violator’s group affiliation. Cognition. 2012;124:325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MFH, Svetlova M, Johe J, Tomasello M. Children’s developing understanding of legitimate reasons for allocating resources unequally. Cognitive Development. 2016;37:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sen A. The idea of justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Olson KR. Children discard a resource to avoid inequity. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General. 2012;141:382–95. doi: 10.1037/a0025907. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw A, Olson KR. All inequality is not equal: children correct inequalities using resource value. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4:393. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00393. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigelman CK, Waitzman KA. The development of distributive justice orientations: Contextual influences on children’s resource allocations. Child Development. 1991;62:1367. http://doi.org/10.2307/1130812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of social knowledge: Morality and convention. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. The development of morality. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Child and adolescent development: An advanced course. New York: Wiley; 2008. pp. 473–514. [Google Scholar]

- Turiel E. Morality: Epistemology, development, and social opposition. In: Killen M, Smetana J, editors. Handbook of moral development. 2. NY: Psychology Press; 2014. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Wainryb C, Shaw L, Laupa M, Smith KR. Children’s, adolescents’, and young adults’ thinking about different types of disagreements. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:373–386. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warneken F, Lohse K, Melis AP, Tomasello M. Young children share the spoils after collaboration. Psychological Science. 2010;22:267–273. doi: 10.1177/0956797610395392. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610395392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellman HM, Liu D. Scaling of theory-of-mind tasks. Child Development. 2004;75:502–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00691.x. http://doi.org/10.111/j.1467-8624.2004.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.