Abstract

In the quest for better medicines, attention is increasingly turning to cell-based therapies. The rationale is that infused cells can provide a targeted therapy to precisely correct a complex disease phenotype. Between 1987 and 2010, autologous macrophages (MΦs) were used in clinical trials to treat a variety of human tumors; this approach provided a modest therapeutic benefit in some patients but no lasting remissions. These trials were initiated prior to an understanding of: the complexity of MΦ phenotypes, their ability to alter their phenotype in response to various cytokines and/or the environment, and the extent of survival of the re-infused MΦs. It is now known that while inflammatory MΦs can kill tumor cells, the tumor environment is able to reprogram MΦs into a tumorigenic phenotype; inducing blood vessel formation and contributing to a cancer cell growth-promoting milieu. We review how new information enables the development of large numbers of ex vivo generated MΦs, and how conditioning and gene engineering strategies are used to restrict the MΦ to an appropriate phenotype or to enable production of therapeutic proteins. We survey applications in which the MΦ is loaded with nanomedicines, such as liposomes ex vivo, so when the drug-loaded MΦs are infused into an animal, the drug is released at the disease site. Finally, we also review the current status of MΦ biodistribution and survival after transplantation into an animal. The combination of these recent advances opens the way for improved MΦ cell therapies.

Keywords: Gene editing, macrophages, cell therapy, drug delivery, cell polarization

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

A variety of cell-based hematopoietic products have been used in therapies for over 50 years including: platelets, granulocytes, bone marrow and most recently engineered anti-cancer targeted T-cells. To place these advances in perspective, the original cell-based therapy, blood transfusions, required almost 100 years of research progress which included: an understanding of the role of microbes in infectious disease, the development of sterilization and blood storage techniques, and most importantly, a delineation of the importance of matching blood group antigens on donated blood cells to those on the recipient’s blood cells [1]. The development of nucleated cell-based therapies emerged in the mid-1980s when investigators started to harness the innate biology of various hematopoietic cells for therapeutic benefits. In the area of cancer treatments, this period generated great excitement in applications of T-cells and macrophages [2]. In the past 15 years, T-cell therapeutics for blood-borne tumors have moved forward [3] due to advances in: immunology, cancer biology, developmental biology, cell engineering and improvements in methods of cell production (reviewed in [3]).

The inception of macrophage (MΦ)-based therapy can be traced to Dr. Isaiah Fidler who was an early advocate of using MΦs to interfere with tumor metastases. He isolated MΦs from the peritoneal cavity of C57Bl6 mice bearing a B16 subcutaneous tumor and stimulated them with a lymphocyte extract isolated from rats sensitized to the mouse B16 tumor. The “activated” C57Bl6 MΦs were then re-injected via the i.v. route into C57Bl6 mice that had previously been tumored via the i.v. route with the B16 melanoma. He observed a significant decrease in pulmonary metastases [4]. His suggestion that, ‘results support the role of cytotoxic macrophages in the defense against neoplasia …and rendering them cytotoxic may provide a possible approach to therapy’ was also based upon prior studies [5, 6]

Since Fidler’s early publications the use of MΦs for therapeutics has advanced into three fronts: 1) Ex vivo educated or generated cells, which exploit the innate properties of MΦs, 2) MΦs as delivery vehicles for small molecules, plasmid DNA and other therapeutics, and 3) Genetically engineered MΦs, which are augmented to allow ex vivo generation or in ways to further their therapeutic benefit. To understand the current rationale for these approaches it is necessary to know something about the origin of MΦs, the plasticity of their phenotypic expression programs, their ability under certain circumstances to divide and their fate under normal circumstances.

2. Tissue Macrophages

2.1 Origins of Tissue Macrophages

MΦs are distributed in all organs where they serve critical functions in maintaining homeostasis in adult tissues [7]. Tissue specific MΦs are involved in phagocytosis of dead and infected cells, maintain T cell tolerance in healthy tissues and initiate immune responses upon bacterial infection [8–10]. MΦs can be best viewed as tissue auxiliary cells that carry out surveillance for tissue integrity, maintain tissue turnover and recruit the immune system to overcome larger tissue damage. In cancer, tumors promote normal MΦ functions of tissue repair preferentially over inflammatory responses for the benefit of tumor growth [11].

For 40 years the dominant theory stated that all MΦs originate from bone marrow derived monocytes based on classic studies by Zanvil Cohn’s laboratory at Rockefeller University in the 1960/70s [12]. This view has been dramatically changed in the light of high resolution fate mapping studies that demonstrate the mixed origins of tissue resident MΦs with minimal contribution of bone marrow derived cells during homeostasis [13]. Tissue resident MΦs are deposited during embryonic development originating from yolk sac cells as early as embryonic day 8.5 (microglia progenitors, subset of heart and liver MΦ progenitors) and from fetal liver after gastrulation (Langerhans cells in skin, spleen, heart, lung, peritoneum, kidney MΦs) [14–18]. In homeostatic conditions in most adult tissues, MΦ populations are maintained by self-renewal [19]. Monocyte-independent replenishing of steady state MΦ numbers is regulated in tissues by MafB dependent repression of MΦ specific enhancers which control self-renewal genes common to embryonic stem cells [20]. However, the signals which regulate MafB dependent repression remain unknown. Self-renewal of MΦs can also be induced in disease conditions exemplified by IL-4 dependent signaling in helminth infection models where the immune response is primarily regulated by local expansion of tissue MΦs [21].

The exceptions to the observation that most tissue MΦs are replaced by tissue resident precursors occurs in MΦs located in high antigenicity environments, such as dermal and intestinal MΦs as well as in most heart MΦs. These sites are replenished at steady state, by bone marrow derived monocytes that undergo differentiation into tissue specific MΦs upon entry into the tissues [22–24].

Inflammatory signals during infection or in a tumor microenvironment cause an influx of Ly6Chigh Ccr2+ monocytes to disease sites. This increases local MΦ concentration leading to a mixture of locally derived and bone marrow generated cells [25]. Embryonically derived MΦs can be partially replaced by bone marrow derived monocytes in conditions that deplete resident tissue MΦs [26]. Monocyte-derived MΦs can thus establish a new population of cells that closely resemble the tissue specific MΦ phenotype that was acquired from the initial embryonically derived cells. In MΦ-depletion studies in heart, liver and spleen, depleted embryonic MΦs are replaced by bone marrow monocyte-derived MΦs. These results highlight the complex interplay between bone marrow derived cells and locally renewing tissue MΦs [26].

Therapeutically, the plasticity of monocyte-derived cells, to adopt local specific MΦ functionality, is critical for potential cell therapy applications that aim to replace local MΦ populations with engineered cells. In animal models of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, in which there is a defect in alveolar MΦ production, adoptively transferred wild type alveolar MΦs assume lung specific function and have demonstrated very long persistence (up to one year duration of the experiment) [27, 28].

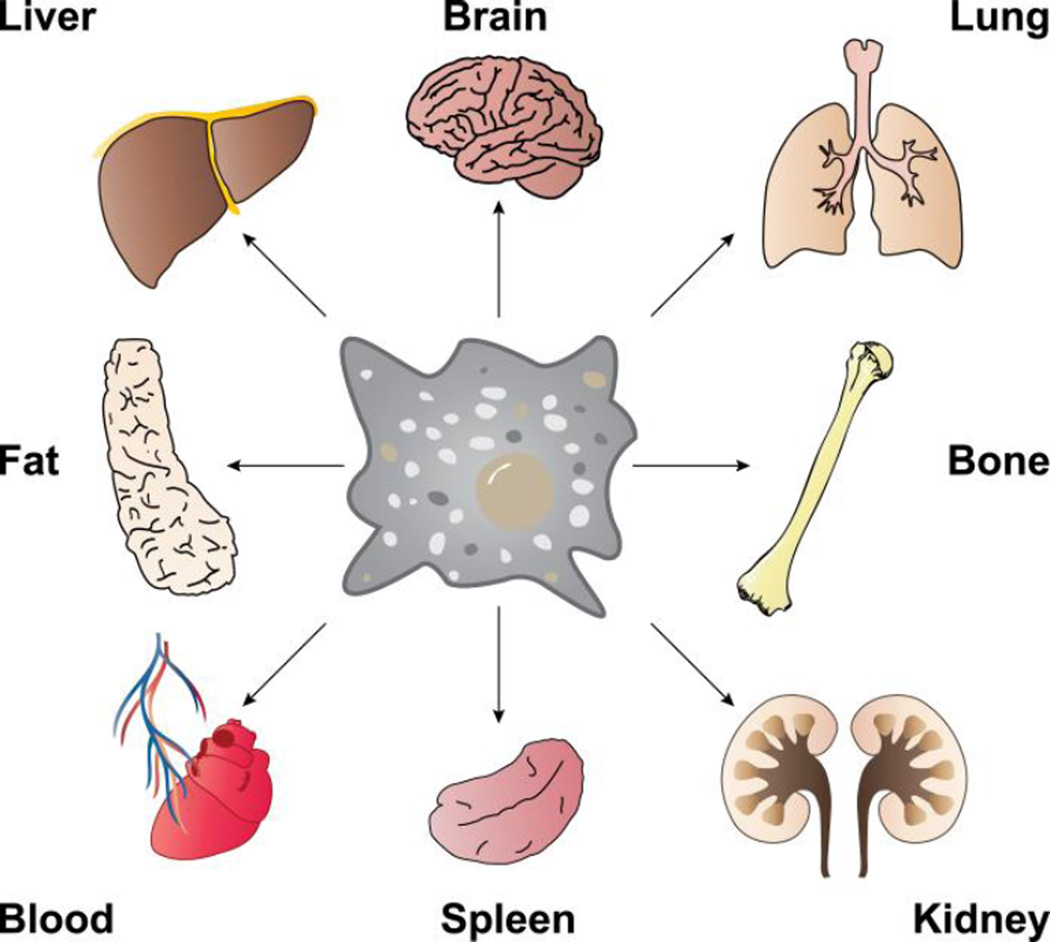

Gene expression programs of the known tissue-specific MΦ populations are highly diverse, and mirror specific functions required in a given organ as well as functions required in distinct compartments of the same organ (Figure 1). However, transcription factors and the signals that establish tissue-specific gene expression programs in MΦs, are largely unknown. The few exceptions include: heme responsive Bach1 in red pulp MΦs, lipids sensing PPARγ in alveolar MΦs or retinoic acid induced Gata6 in peritoneal MΦs [29–31]. Recent discoveries indicate that tissue environment derived signals induce expression of master transcription factors; that in combination with MΦ lineage determining transcription factors PU.1 and C/EBP, lead to specific transcriptional programs and cellular phenotypes [32]). Such a combinatorial model can explain the tissue environment dependent diversification of monocyte-derived MΦ populations. The model also rationalizes MΦ tissue transplantation experiments. For instance, placing peritoneal MΦs into an alveolar environment leads to a remarkable 70% genome-wide gene expression reprogramming to reflect the newly acquired alveolar MΦ phenotype [33].

Figure 1.

Tissue-resident macrophages can be found throughout the body in virtually all tissues and organs. These macrophages perform a variety of tasks including phagocytosis of dead cells and debris, modulating innate immune responses, maintaining homeostatic growth, repair and metabolism. Macrophages from different tissues have distinct gene expression profiles, but in some cases, due to phenotypic plasticity, macrophages from one tissue can be transplanted to another and adopt the new tissue-resident profile [33].

This exceptional plasticity of tissue MΦ phenotypes, combined with the centrality of a variety of subtypes of MΦs in control of tissue homeostasis and activation of immune responses to outside and internal insults, make MΦs ideal building blocks for a variety of future tissue replacement therapies [34].

2.2 Sources of Macrophages for Therapeutic Purposes

Excluding transformed MΦ-like cell lines, two principal sources of MΦs have been utilized to produce ex vivo MΦs that can be modified for therapeutic purposes. The first set of techniques is based on differentiating a collection of monocytes from blood or from extracted bone marrow into MΦs in M-CSF1 containing media. The second source is by isolation of pre-existing MΦs from body cavity lavages (alveolar, peritoneal) of resident or elicited (e.g. thioglycollate, peptone) MΦs [35]. Once in cell culture, MΦs can be further incubated with immune stimulators (e.g. LPS, cytokines) to induce different polarizations that mimic in vivo phenotypes [36].

The classical MΦ collection methods, such as those used to prepare bone marrow derived MΦs from lavages, have a large body of literature and are well characterized but can only be used to produce relatively small numbers of a particular type of MΦ. Other MΦ elicitation techniques (polyacrylamide beads, proteose peptone) are often poorly characterized which leads to in vivo studies that can be difficult to compare and interpret both within and across laboratories. These wide ranging collection methods also produce MΦs with different phenotypes. Regardless of the collection method employed, monocytes or MΦs are produced in relatively low numbers. Plus, these MΦs typically fail to proliferate as they differentiate in vitro and are difficult to genetically modify, making cell line generation and genetic engineering infeasible.

For the purpose of autologous therapies, each batch of MΦs requires returning to the donor. The reason is that in vitro, monocytes exit cell cycle after 7–10 days of proliferation and differentiation and do not divide; moreover, monocytes have a short life span as they differentiate further into MΦs [37, 38]. To address this need for generating large numbers of MΦs, an alternative strategy that has emerged over the last 10 years is production of MΦs from proliferative, conditional developmentally-arrested, primary MΦ progenitors. Non-transformed self-renewing progenitor cells are established by overexpression of a transcription factor, Hoxb8, in bone marrow progenitors, in media supplemented with GM-CSF or Flt3L [39, 40]. Hoxb8 activity leads to the blockade of progenitor differentiation. This results in rapidly proliferating, clonable cells. Removal of Hoxb8 activity allows progenitors to resume differentiation and produce differentiated MΦs. Hoxb8-GM-CSF progenitors differentiate by default into MΦs when Hoxb8 activity is removed [40]. Hoxb8-Flt3L cells are more primitive progenitors that can be differentiated into MΦs in M-CSF1 containing media after Hoxb8 removal [39].

Conditional progenitor-derived MΦ production has several major advantages over classical MΦ production methods. First, large numbers of progenitors can be accumulated prior to initiating differentiation. This theoretically enables unlimited cell numbers to be produced. Second, conditionally immortalized progenitors are rapidly dividing cells which enables genetic engineering far more readily than using non-dividing MΦs. Unlike classical monocyte or MΦ isolation techniques, a single cell isolation from the donor is sufficient to generate conditional progenitor lines that can be stored frozen for use in an unlimited number of cell transfer experiments. These attributes dramatically reduce cell production costs while providing a well characterized clonal line for future experiments. The current disadvantage is that conditional progenitor cell based-MΦs have not yet been extensively characterized, hence investigators are unfamiliar with their properties in comparison to directly isolated MΦ populations with their decades of use in research. Fortunately, technological advances in MΦ molecular phenotype characterization in vivo have delineated a very large collection of markers that describe MΦ functional states [41]. This knowledge base can be used to categorize the conditional progenitor-derived MΦs that have been differentiated in vitro.

2.3 Functional Polarization of Macrophages

MΦs carry out tissue-specific homeostatic functions by regulating gene expression programs in response to the local tissue environment. Such reversible transcriptional programming is termed as MΦ polarization, to distinguish it from permanent tissue-specific MΦ differentiation. Cell-cell contacts and soluble signaling molecules like cytokines, growth factors and extracellular polymers dictate functional polarization of MΦs through intracellular and transmembrane sensors. Historically, MΦ polarization was depicted as a bipolar system of classically (interferon gamma, IFNγ) activated pro-inflammatory MΦs designated as the M1 state and alternatively (IL-4) activated anti-inflammatory MΦs as the M2 state of polarization; to be analogous to Th1 and Th2 type of responses of T cells [11, 42].

It is apparent now that MΦ polarization is a continuum of overlapping functional states that involve a plethora of signals and corresponding dynamic gene expression programs. Given the diversity of MΦ gene expression responses to environmental stimuli, it is critical to describe in detail, the workflow of ex vivo MΦ manipulations and to characterize the molecular and cellular properties of the resulting therapeutic cell lines to meaningfully interpret, reproduce or predict outcomes in MΦ based therapies [43]. Understandably this has not been the case in early MΦ adoptive transfer experiments because of the lack of knowledge of MΦ phenotypes.

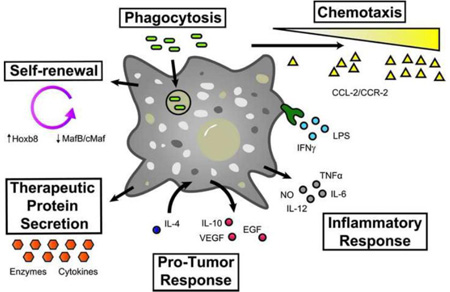

Changes in MΦ phenotype in response to soluble ligands (e.g. IL-4 and IFNγ) are primarily mediated by NFκB, Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription (STAT) and Interferon Response Factor (IRF) transcription factor families [44]. Ex vivo produced MΦs can be polarized with a variety of defined stimuli, resulting intransient acquisition of specific gene expression programs and functionality. Historically, LPS and IFNγ have been used to induce proinflammatory cytokine expression (IL-12, IL-6, TNFα) and nitric oxide production [44, 45]. These transcriptional responses are mediated by JAK-STAT (STAT1/2) and TLR4 signaling that activate NFκB and Irf5/Irf8 transcription factors.

A distinct gene expression program is induced by IL-4 that upregulates MΦ mannose receptor expression and arginase production along with a distinct set of anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL10, CCL17). IL-4 signaling is mediated by STAT6 and Irf4 transcription factors [46]. At the enhancer level the distinct transcriptional responses are exclusive, suppressing the alternative gene expression program. Irf5 recruits transcriptional activators on IFNγ target genes in response to TLR4 signaling while also binding to IL-4 target gene promoters but acting as a transcriptional repressor of these genes [47]. Similarly STAT1 downstream IFNγ receptor directs transcriptional programs that induce pro-inflammatory polarization while suppressing STAT6 dependent activation of anti-inflammatory genes. Different polarization programs are independent modules that can be silenced without negatively affecting competing transcriptional programs. STAT6 knockout cells are unable to mount the IL-4 dependent transcriptional program but are still competent to induce gene expression in response to IFNγ [48]. It is thus possible to engineer MΦs with exquisitely selective sensitivity to tissue environment signals. After cell transfer, this tactic could reduce side effects of cell therapies while retaining the intended ex vivo induced functional polarization in vivo. Detailed knowledge of the transcriptional circuitry of reversible MΦ polarization may thus enable genetic engineering to “lock” ex vivo-produced MΦs polarizations into permanent functional states for therapeutic use.

In conclusion, the last decade of research on the molecular underpinnings of MΦ differentiation, functional diversity and cell signaling in tissues and in vitro environments should enable much better informed strategies to harness this cell type for therapeutic use. This can now be accomplished through genome engineering to customize responses in disease microenvironments or to small molecule effectors that can be administered to regulate MΦ.

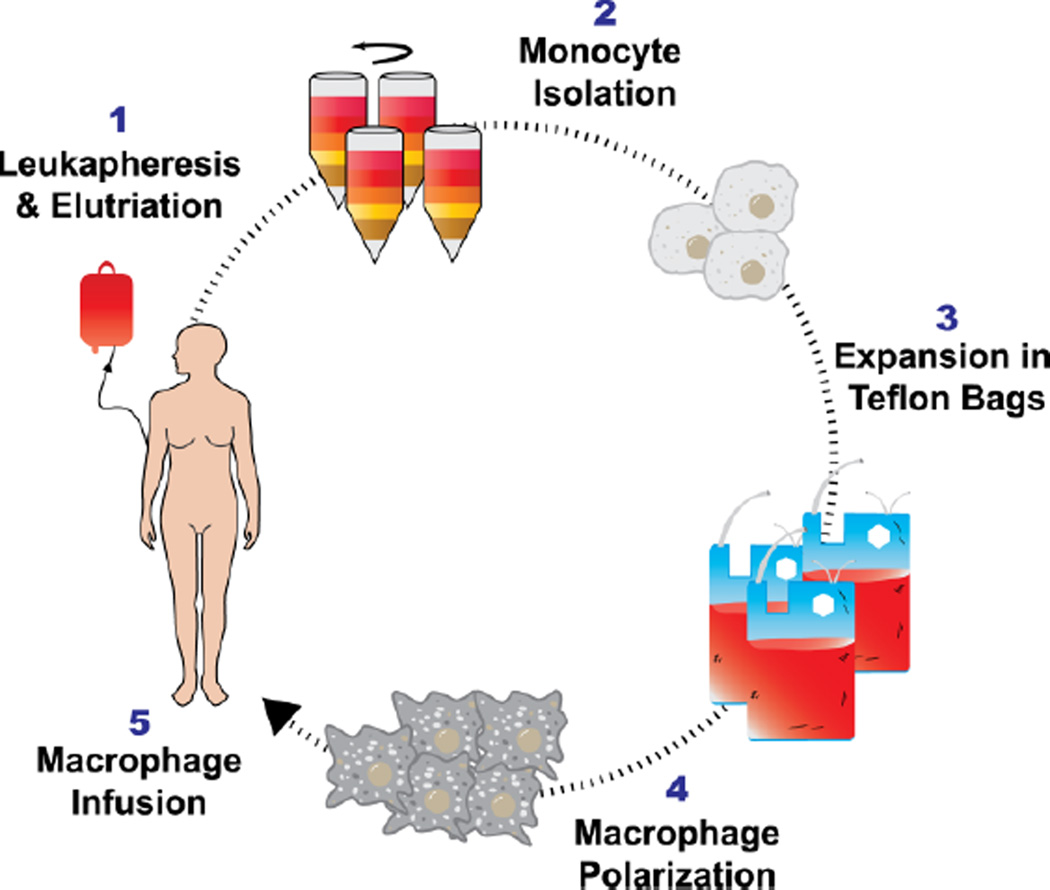

3. Human Clinical Trials: ex vivo educated or generated cells

The use of ex vivo educated cells has the longest history in MΦ-based therapies. The concept is supported by the discovery of high levels of monocyte and MΦ recruitment towards tumors in vivo and animal experiments demonstrating the cytotoxic potential of IFNγ-treated primary MΦs [4, 49, 50]. Multiple groups attempted to develop a therapy that would collect blood monocytes, proliferate and differentiate these monocytes into MΦs, “educate” MΦs into a cytotoxic phenotype ex vivo, and inject these MΦs into patients, whereupon they would hijack existent MΦ recruiting signals from the tumor or the metastatic sites to traffic to and destroy the tumor [51]. A host of secondary technologies were developed in order to bring these ideas to reality, most notably the abilities to harvest and purify monocytes from human blood using leukapheresis and elutriation [52, 53] and then culture these cells in sterile conditions to produce up to 109 cells on a weekly basis per patient (Figure 2). Substantial efforts were made to utilize these cells as an anti-cancer therapeutic, with the earliest human clinical trials occurring in the mid-1980s against multiple cancer types [51].

Figure 2.

Therapeutic macrophages collected from human blood via leukapheresis and elutriation. Monocytes are purified from blood via leukapheresis and elutriation, followed by culture in Teflon bags. Monocytes proliferate and differentiate in media with cytokines (IFNγ and GM-CSF) over a period of 7–10 days, generating up to 107-109 cells per patient.

Despite the persistent attempts to use this methodology against multiple cancers, regardless of the dose, schedule and methods of administration, most of the clinical trials were unsuccessful in even slowing the progression of cancer [51]. A review of these trials in the context of the current understanding of MΦ biology and cell-based therapeutics, reveals several important considerations for the future development of MΦ-based cell therapies ([51], Table 1).

Table 1.

Human Clinical Studies using Macrophages

| Cell Type + Activation Method |

Route+ Dose | Disease | Effect | PK/BD | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukapheresis and elutriation, cultured 7 days, 18h in 1000U/mL IFNγ |

i.p., 3.5×107 cells/dose, weekly for 8 weeks |

Colorectal cancer with peritoneal metastasis |

N/A | In-111 label, signal stayed within the peritoneum for 5 days, blood peaked at 9% at 48h, no transfer to other organs |

[55] |

| Leukapheresis and elutriation, cultured 7 days, 18h in 200U/mL IFNγ |

i.v. or i.p., 1- 4×108 cells/dose, escalating every 2 weeks (i.v.) or weekly (i.p.) |

Systemic metastasis (i.v.), Peritoneal metastasis (i.p.) |

Only therapeutic effect: 2/7 disappearance of peritoneal ascites |

N/A | [53] |

| MΦ Activated Killer (MAK): Leukapheresis and elutriation, cultured 6d in 500U/mL GMCSF and 18h in 166U/mL IFNγ |

i.v., 0.1–5×108 cells/dose, escalating weekly |

Non-small-cell lung cancer |

N/A | In-111 label, greatest signal in lungs at 24h, migrating to liver and spleen at 72h, decreasing thereafter |

[60] |

| MAK, Activated with mifamurtide |

i.p., Escalating weekly dose from 107 109/dose |

Peritoneal carcinomatosis (ovarian, pancreatic, gastric, appendicieal) |

No therapeutic response. Increase of IL-1, IL-6 and TNFα in peritoneal cavity |

In-111 label, signal stayed in abdominal cavity for up to 7 days, no signal in lungs, liver or spleen, 0.5% in blood |

[62] |

| MAK, patients dosed with 50 µg/m2 IFNγ prior to cell collection |

i.v. via hepatic artery, 1- 10×108 cells/day, 3 sequential days, depending on cell recovery from patient |

Colorectal or stomach cancer with liver metastasis |

No therapeutic response |

In-111, 1h: 18% lung, 56% liver, 7d: 12% lung, 43% liver |

[61] |

| MAK |

i.v., 1×109 cells/dose weekly for 6 weeks |

Colorectal cancer |

No therapeutic response. 11/14 showed progression, 3/14 stabilized |

N/A | [74] |

| MAK, activated with 1ng/ml LPS for 30 mins. Patients dosed with 2–4 ng/kg LPS prior to cell collection |

i.v., 3×106 4×108 cells/dose, escalating weekly for 7 weeks |

Cancer (Colorectal, renal, pancreatic, melanoma or NSC lung) |

Increase in TNFα and IL6 by 40x, 1/9 patients with stable disease (<25% growth), 8/9 showed progression |

N/A | [75] |

| MAK |

i.v., 3×109/dose, 3 doses over 2 weeks |

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma |

Transitory stabilization (n = 8) or partial regression (n = 1) in 9 of 15 patients |

In-111 label, at 72h, lung (6%), liver (24%), spleen (11%), blood (3%) |

[76] |

| MAK |

i.v. or i.p., 1- 2×109 in single dose |

Metastatic ovarian carcinoma |

N/A | In-111 or PET F18-FDG. i.v Accumulation in lungs at 4h (10%), at 24h, liver (50%) and spleen (4%). Accumulation in tumor in 4/10 patients i.p Accumulation in tumor in 4/6 patients |

[63] |

| MAK | Intravesically, 2×108/dose, weekly for 6 weeks |

Superficial Bladder Cancer |

Recurrence occurred significantly less frequent with standard treatment than with cells (12% vs. 38%; p < 0.001) |

N/A | [64, 77] |

| Ixmyelocel-T - bone marrow aspirate enriched for regenerative macrophages and mesenchymal stromal cells by a proprietary process |

Local injection to multiple sites in affected heart or limb, 30- 300×106/dose |

Dilated cardiomyopathy or critical limb ischemia |

Reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (14% treated, 56% control), reduced time to first occurrence of treatment failure |

N/A | [72, 73] |

First, dose-escalation studies in humans demonstrated the relative safety of administering large numbers and frequent doses of autologous MΦs. In the 11 human clinical trials in Table 1, the majority of reported side effects were slight fevers and chills, with no serious side effects at the highest doses (which are limited to ∼109 as that is the largest number of MΦs that can be extracted and cultured from a patient in one leukapheresis) or frequencies (up to one dose every 24 hours for 3 days). In these autologous studies, immune rejection events were not observed. However, when coupled with the fact that none of these trials succeeded in their therapeutic goals, this safety result should be viewed with caution since perhaps a therapeutic dose of MΦs needs to be orders of magnitude larger than was administered in these trials or the viability of infused cells needs to be improved. If we draw a parallel to CAR T-cell therapies, dangerous and deadly occurrences of tumor lysis syndrome and cytokine release syndrome (“cytokine storms”) have been observed in cases of successful tumor destruction by the cell therapy [54]. It is evident that researchers must consider the safety concerns that may arise if conditions can be engineered to enhance the cytotoxicity of MΦs against tumor cells; this could lead to a dangerous milieu of cytokines, dying cells and inflammation.

Second, it is clear from the evolution of clinical trial design and the associated pharmacokinetic/biodistribution studies, that the trafficking potential of the MΦs into tumors was overly optimistic. Early trials injected cells intravenously, hoping to rely on an innate recruiting signal from the tumor to attract the injected cells either directly out of circulation, or from an initial engraftment site (i.e. the lung, liver or spleen) to the tumor. Follow-on studies using Indium-111 labelled cells showed radioactive signals primarily concentrated in the lung immediately post injection, followed by relocation of the signal to the liver and spleen [55, 56]. Distribution of the signal into the tumor was rarely observed and appeared spurious and inconsistent ([51], Table 1). The signal would eventually dissipate from the lung, liver and spleen but trafficking into the tumor did not seem to occur. This pattern of distribution suggests that the MΦs were being primarily trapped in the lungs soon after injection, a result mimicked in the intravenous injection of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) [57–59].

Based on the biodistribution results indicating residence of signal in the lung and liver, investigators began targeting lung [60] and liver [61] cancers. Other trials infused the MΦs directly into the tumor location including intraperitoneal injections in patients with metastatic lesions in the peritoneum [53, 62] and intravesically into the bladder of bladder cancer patients [63, 64]. Initial trial results in treatment of bladder cancer were positive enough to warrant further comparative trials against standard therapies [63]. However, MΦ instillations were not nearly as effective as the standard therapy in the bladder [64]. Since the completion of this trial in 2010, there are few human clinical trials for anticancer MΦ cell therapy listed in clinicaltrials.gov. There is a Russian clinical trial assessing the Safety of Autologous M2 Macrophage in Treatment of Non-Acute Stroke Patients listed on ClinicalTrials.gov (Identifier NCT01845350) although the status of this trial has not been updated since 2013.

Third, it is interesting to note the homogenous methods employed to collect, isolate, culture and prepare the human MΦs for injection. Cells were almost always collected from the blood and isolated using a combination of leukapheresis and elutriation (Figure 2). The monocytes collected from this procedure were then cultured, propagated and differentiated in Teflon bags with GM-CSF for ∼6 days, and then “educated” into a cytotoxic phenotype using 100–1000 U/mL IFNγ for 18 hours prior to injection [55]. This became known as the “Macrophage Activated Killer” (MAK) protocol, and was used with minimal modifications for the published human anticancer clinical trials. While it can be appreciated that the MAK protocol generated high numbers of cells which behaved as expected in vitro [65], the trial data clearly indicates that these cells did not mediate a pronounced antitumor response in patients. As described earlier, significant advances in the understanding of MΦ biology were made concurrently with these trials. The newer discoveries illustrate the importance of cell origin, polarization method and perhaps most importantly, the contextual nature of MΦs, which modify their behavior based on the integration of many signals in the environment [66]. The latter feature is especially important because the tumor microenvironment is capable of providing signals to polarize MΦs towards a M2 tissue repair phenotype, further increasing the malignancy of the tumor [67–69]. It is now apparent that in order to harness the cytotoxic and immunomodulatory nature of MΦs, a nuanced understanding of their development, behavior and disease interaction is required.

A more recent application using MΦs as a cell therapy can be seen in Vericel’s (formerly Aastrom) Ixmyelocel-T [70], an autologous multicellular therapy that is currently undergoing clinical trials for dilated cardiomyopathy and critical limb ischemia. Bone marrow aspirates are collected and differentiated using a proprietary process that yields a mixture of cells enriched for regenerative MΦs and mesenchymal stromal cells, while reducing the overall proportion of other granulocytes. In current clinical trials, 30–300×106 cells are injected once into multiple locations into the affected heart or limb tissue. Vericel has reported that the combination of cells in ixmyelocel-T is able to aid in tissue remodeling and immunomodulation through the secretion of extracellular matrix proteins, anti-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and growth factors [70–72]. Analysis of the MΦ component of the multicellular product revealed high expression of M2 markers (CD206 and CD163), indicative of a regenerative phenotype [71]. However, it is not clear what synergistic effects arise from the other cell types. In a recent clinical trial, Vericel showed Ixmyelocel-T improved symptoms and reduced major adverse cardiovascular events (14% of Ixmyelocel-T treated patients compared to 56% of conventionally treated patients experienced events) in ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy [72]. In a trial for critical limb ischemia, time to first occurrence of treatment failure (amputation, doubling of wound area, de novo gangrene, mortality) increased significantly and a reduction, but not statistically significant, in total events was achieved [73]. The results from Vericel represent an important accomplishment in the development of MΦ-based cell therapies and underscores the importance of MΦ phenotype on potential disease targets for MΦ therapies.

4. Recent Animal Trials: Ex vivo modified macrophages

The recent studies using ex vivo educated MΦs to treat diseases in various animal models are described in the following sections (Tables 2–4).

Table 2.

Minimally modified therapeutic macrophages in animal models

| Cell Type + Activation Method |

Route + Dose |

Disease | Effect | PK/BD | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD11b+ cells isolated from spleens, polarized to M1 (2.5 µg/ml LPS for 2h), M2 IL- 4/13 (10ng/ml for 48h) or M0 (untreated) |

i.v., 1×106 cells injected 5 days post induced nephropathy |

Adriamycin- induced nephropathy in SCID mice |

M1/M2 localized to kidneys, M2 protected against structural and function damage |

DiI label, combined with F4/80-FITC costain, non- quantitative. Detection in kidney, spleen and liver 24h post injection, accumulation in kidney up to day 21 |

[79] |

| CD11b+ cells isolated from bone marrow, 10 ng/ml M-CSF for 6 days. M2 polarization: IL- 4/13 (10ng/ml for 48h) |

i.v., 1×106 cells injected 5 days post induced nephropathy |

Adriamycin- induced nephropathy in SCID mice |

Bone marrow derived M2 MΦs did not prevent renal injury due to M-CSF induced proliferation causing phenotype instability |

CFSE label, non- quantitative. Detection in spleen at d2, increasing at d23 |

[78] |

| Autologous Microglia derived from bone marrow of young (3 mo) or aged (17 mo) mice |

Intranasal or i.v., 106 single cell dose |

Healthy C57BL/6 |

Only microglia from young mice migrate to brain in both young or aged mice |

Y-Chromosome specific qPCR for detection in lung, blood kidney and liver, brain, non- quantitative |

[81] |

| BMDM in M- CSF supplemental media from L929 cells for 7- 10 days. M1: 10 ng/ml IFNγ |

Locally to four sites surrounding catheter, 106 single cell dose |

Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) biofilm infection in catheter implanted in flank tissue |

M1-polarized MΦs significantly impair biofilm formation and bacterial burden in catheter and nearby tissue |

N/A | [82] |

Table 4.

Gene modified macrophage therapies in animal models

| Cell Type + Modification |

Dose | Disease | Effect | PK/BD | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autologous or allogenic blood monocytes + GM- CSF |

i.v. (ear vein), 3×107 cells single dose |

Arteriogenesis post arterial ligation in rabbits |

Allogenic, but not autologous, GM- CSF expressing monocytes resulted in augmented vessel growth |

β-Gal expression, non- quantitative. Infiltration in ligation site at 24h (no data on other sites) |

[121] |

| CD14+ human monocytes + P450 reductase for prodrug cyclophosphamide (CPA) |

i.p., 2×106 cell single dose, 1mg CPA weekly |

HU or TOV21G tumor xenograft in nude mice |

HU: Median survival increase from 21 to 49 days, TOV21G: From 56 to 106 days |

N/A | [120] |

| iPSC-derived myeloid line + IFNβ |

i.p., 2×107 cells/dose, 3 doses/week for 3 weeks |

NUGC-4, MIAPaCa-2 in SCID mice |

IFNβ modified cells inhibited tumor growth; NUGC-4: 5x (untreated) vs 2x, MIAPaCa-2: 2x vs 0.1x |

N/A | [116] |

| RAW264 + GDNF, catalase or luciferase, Polarization: M1 (IL4 (20ng/ml) 48h) |

i.v., 5×106 cells, (single dose) |

Parkinson’s Disease in wildtype Balb/c mice (6-OHDA induced) |

Reduced neuroinflammation, improved performance on rotarod behavioral tests |

Luciferase transfected cells injected, significant difference between diseased and healthy mice in signal visualized in brain |

[98, 107] |

| Mouse BMDM in 10ng/ml GM-CSF + 5ng/ml M-CSF, or lin Sca1+ c-Kit+ cells (differentiation through multiple cytokine mixes - see ref) + Csf2rb |

Endotracheal instillation, 2×106 cells (single dose) |

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (Csf2rb−/−) |

Prevention of mortality and normalized disease-related biomarkers. |

Persistence of at least one year. Proliferation and selective advantage leads to 69% of cells in bronchial lavage to be CD131+ (Csf2rb) |

[28] |

| Wildtype mouse BMDM or Human MΦs differentiated from CD34+ cord blood in GM-CSF |

Endotracheal instillation, 2×106 cells (single dose) |

Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis (Csf2rb−/−) |

Prevention of mortality and normalized disease-related biomarkers |

Persistence of at least nine months in lungs |

[27] |

| RAW264 + doxycycline inducted - intracellular rabbit carboxylesterase (converter of prodrug irinotecan to SN38) |

i.p., 2×106 cells/dose (day 5, 9, 13 post tumoring), doxycycline (day 7, 11, 15) |

i.p. Pan02 pancreatic tumor |

Increased average survival of 2.5 days (10%) compared to doxycycline control |

Tracking of PKH26 fluorescent label on RAW264 cells injected i.p found label only in tumor |

[122] |

| IFNα restricted to tumor-associated TIE2+MΦs |

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

MMTV-PyMT primary and metastatic breast tumor |

5x reduction of total lung metastatic area, 3x reduction of primary tumor size |

N/A | [117] |

4.1 Macrophages without extensive modifications

In an Adriamycin-induced nephropathy, both M1 and M2 ex vivo polarized spleen- or bone marrow-derived MΦs injected (1×106 cells 5 days post nephropathy induction) via the tail vein were capable of trafficking to the kidney [78, 79]. Unfortunately, this trafficking was not quantified, though injected MΦs were detected in the kidney up to 23 days post-injection by histology. However, only M2 polarized spleen-derived MΦs provided any therapeutic benefit, though it is unclear how long the MΦs maintained a M1 or M2 phenotype. While the enhanced therapeutic benefit of M2 MΦs over M1 MΦs was fully expected, the effect of cell origin was surprising. The authors of the studies suggested that this was because the bone marrow-derived MΦs maintained a certain degree of proliferation, resulting in the eventual loss of M2 polarization and adoption of an M1 phenotype. Maintenance of a M1 phenotype may be possible by overloading MΦs with iron, which has been shown to hold MΦs in a proinflammatory state in human chronic venous ulcers that impairs wound healing [80].

In another study, 1×106 autologous microglia (brain-resident MΦs) derived from the bone marrow of young (3 mo) and aged (17 mo) male mice were transplanted intranasally or intravenously into healthy female mice and their presence in various organs detected using Y-chromosome specific qRT-PCR [81]. Twenty-eight days post transplantation, only microglia derived from young mice were found in the brains of aged mice, and aged microglia could not be found in either young or aged mice, regardless of route of administration (no data was provided regarding the number of microglia which reached the brain). The authors hypothesize that this surprising result may be due to the changes in brain signaling during aging; most notably an increase in MΦ-attractive chemokines (MIP-1α, MIP-1β and CCL5) and survival signals (CD40LR). The results in the kidney and brain illustrate the importance of the origin of the MΦs and their target destination in determining the behaviors of transfused MΦs in disease models. Proinflammatory MΦs have also been shown to impair staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and bacterial burden in a catheter-associated bacterial biofilm mouse model when 106 MΦs are locally injected in catheter-adjacent tissue. Importantly, when compared to neutrophils or naïve MΦs, proinflammatory MΦs were able to overcome and reprogram the local environment to a proinflammatory milieu as shown by enhanced expression of proinflammatory proteins (CXCL9, CCL5, IFNγ, IL-10, IL-17, CXCL2 and IL-6) in the local tissue [82].

4.2 Macrophages as Delivery Vehicles

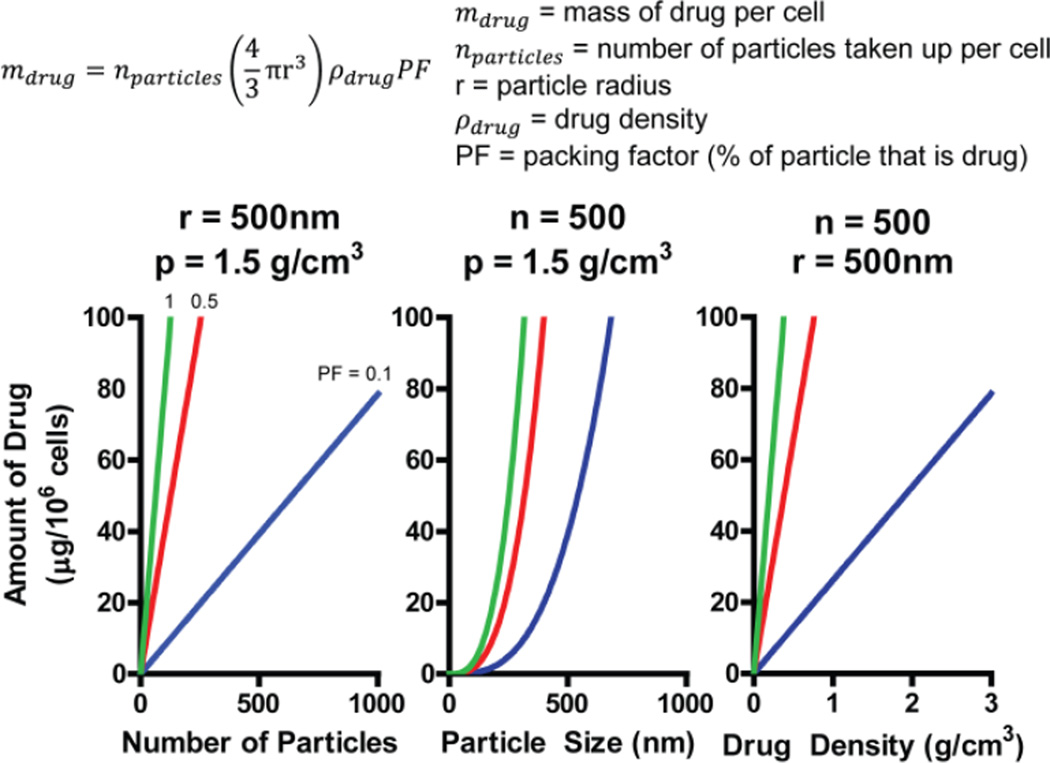

The defining attribute of MΦs is their ability to phagocytose material via a variety of mechanisms; hence loading appropriately modified micro and nanomaterials such as: drug crystals, bacteria, gold particles, inert emulsions or liposomes can result in an appreciable level of drug per MΦ. A substantial amount of literature has been published with respect to drug delivery to the reticuloendothelial system [83–88], the effects of varying size and shape of materials for targeted drug delivery [89–93], and trafficking of drugs at the intra- and extracellular level [94–96]. From a purely theoretical basis the highest level of drug loading in MΦs occurs when sparingly soluble drug crystals are loaded. The amount of drug which can be loaded into a MΦ will vary based upon the number of drug particles taken up per cell, drug particle size, drug density and packing factor (percentage of particle that is drug) (Figure 3). Assuming realistic values for these variables, one can reasonably expect an approximate range of 10–100 µg/1×106 cells. Additionally, the drug cannot kill the MΦ before it reaches the target and it must be able to leave the MΦ once it reaches the target. The prodigious phagocytic ability, when combined with the trafficking of MΦs to disease sites, especially highly inflammatory sites, has inspired multiple other groups to explore using MΦs as drug delivery vehicles, reviewed in [97].

Figure 3.

Modeling of macrophage uptake of drug particles shows a theoretical uptake of 10–100 µg per 106 cells. Drug uptake is a function of number of particles phagocytosed (nparticles), drug particle radius (r), drug density (ρdrug) and packing factor (PF -percentage of particle that is drug). Based on the equation, theoretical drug loading is presented as a function of nparticles, r and ρdrug at PF values of 0.1 (blue), 0.5 (red) and 1 (green).

The potential advantage of using MΦs for drug delivery is multi-faceted. Material contained inside MΦs can enjoy an extended half-life as the encased drug is not rapidly eliminated via renal excretion or liver metabolism, protected from immediate immune recognition, and from clearance by the endogenous RES system. In addition to an extended circulation half-life, MΦs can enable slow release of drug, as seen in the studies from the Gendelman and Batrakova laboratories [98–104]. HIV antiretroviral drugs were delivered via MΦs in a humanized mouse model to HIV infected cells implanted in the CNS and a sustained release of drug at a concentration capable of inhibiting HIV replication was observed over 10 days with no reported side effects [101, 102, 105]. In a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease, RAW264 MΦs injected intravenously were found to migrate into the space surrounding the insult that induced the Parkinson’s phenotype and delivered plasmid DNA expressing GDNF to nearby cells. The authors speculate that the DNA was delivered from the MΦ into the surrounding cells via exosomes [98].

While ensuring the MΦs will carry the drug is easy, delivery of the drug once the MΦ reaches its target site remains a challenge. To date, most publications have exploited the passive release of the drug through cell death, slow release of a drug capable of crossing the cell membrane, or through an exosome mechanism (Table 3). One tactic to ensure the potentially toxic drug cargo does not kill the MΦ prior to delivery is to package the drug into a liposome as described for doxorubicin instead of using the free drug [106]. This approach seems to rely on the death of the MΦ when it reaches the target. This tactic could be difficult to control if MΦs fail to localize in large enough numbers to deliver an effective dose at the target site.

Table 3.

Macrophages as drug delivery vehicles in animal models

| Cell Type + Modification |

Dose | Disease | Effect | PK/BD | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMDM in 1000U/ml M- CSF + catalase mixed with PEI- PEG block copolymer (Nanozyme) |

i.v., 25ug nanozyme per 1×106 cells, 5×106 cells/dose |

Parkinson’s Disease in wildtype Balb/c mice (MPTP induced) |

Reduced microgliosis, increased dopaminergic neuronal survival |

I-125 labeled catalase, 24h post injection: spleen (0.6%), liver (1.2%), lung (0.6%), kidney (1%), brain (0.5%), improved clearance, half- life, AUC, MRT and Vd in BMDM/nanozyme |

[99, 100, 103] |

| Murine BMDM (10d in 2mg/ml M-CSF) + Indinavir (IDV) or Super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) |

i.v., 2×107 cells/dose, incubated with 5×10−4 M IDV for 12 h. Injected prior to viral challenge |

Hu-PBL- NOD/SCID mice, reconstituted with human PBLs, i.p injected with HIV-1 ADA |

51% reduction in HIV-1 p24 antigen at day 14. Enhanced CD4+ T-cell survival |

Sustained response over 10 days, 4–50 fold of clinical effective plasma levels in multiple organs (liver, spleen, lung, lymph nodes) |

[104] |

| Peritoneal MΦs from Thioglycollate treated mice + liposomal doxorubicin, iron oxide |

i.v., Doxorubicin: 5×106 cells/wk, 5 weeks, 30 µg dox |

Xenograft A549 subcutaneous and metastatic tumor in nude mouse |

Reduced tumor volume when compared to equal amount of free doxorubicin |

IO labeled cells detected by Prussian blue staining in s.c. tumor. Not quantitative |

[106] |

| Peritoneal MΦs from PBS flush + Gold nanoshells |

Intratumoral and peritumoral, 0.1375 pM nanoshells/100 cells/dose |

Xenotransplant SNU-1041 human pharyngeal cancer line in nude mice |

Cell death observed near injection sites |

Gold nanoshells remained at injection site. Not quantitative |

[110] |

| CD14+ monocytes from human blood buffy coat + Gold nanoshells |

i.v., 107 cells 4 wks post tumoring |

Human MDA- MB-231 BR brain metastatic xenograft in nude mice |

N/A (photothermal therapy not performed) |

Tracking by anti- human CD68 and fluorescent microspheres show trafficking of monocytes from lungs to liver, spleen and brain metastasis |

[112] |

Selecting a sparingly soluble drug that is relatively non-toxic to the MΦ and can be released as it becomes soluble is one effective innovative method. HIV antiretroviral therapy drugs were milled and combined with block co-polymers to form drug crystals known as NanoART [101, 102, 105] that were readily phagocytosed by MΦs, up to 45 µg/1×106 cells, and solubilized slowly in the cell, enabling slow release. The time scale for this release was such that MΦs could be injected, migrate to various tissues, and still contain the vast majority of the drug. The drug crystal slowly dissolved, and since the drugs can permeate cell membranes, the drug was slowly released out of the cell.

A similar mechanism was used to deliver Nanozymes in a Parkinson’s disease model [99, 100]. Nanozymes are a combination of the therapeutic enzyme, catalase, with block co-polymers. Bone marrow derived MΦs readily phagocytosed Nanozyme, and increased the circulation half-life and tissue AUC of catalase when compared to injection of the free protein (further discussed in section 5) [99, 100]. These methods could in theory also be applied to deliver drugs to other conditions with inflammatory pathologies that recruit MΦs, such as, bacterial infections, cancer and chronic inflammatory diseases.

An alternative release mechanism proposed by Batrakova and co-workers is that the MΦ can package and release certain cargos in exosomes [98, 107]. Exosomes are small vesicles released by all cells which can contain protein, DNA and/or RNA. The relevance is that exosomes have been shown to act as an intercellular signaling transport system [108] and could potentially provide delivery over short distances to adjacent cells after the MΦ has migrated to the disease site [98, 107]. The contents of an exosome is unique to the cell from which they originate, and often contains markers from the cell of origin [108]. Exosomes isolated from MΦs which have been transfected with plasmid DNA have been found to carry the protein produced by the transfected plasmid DNA, the mRNA for the protein and the transfected plasmid DNA [98, 107]. Batrakova’s group has demonstrated exosomes isolated from in vitro MΦ cultures can act as delivery vehicles for protein, plasmid DNA or mRNA [109]. In effect, the exosomes act as horizontal gene transfer vehicles for plasmid DNA or mRNA to adjacent cells.

An interesting approach to achieve a therapeutic effect is to bypass the need for drug to leave the MΦ by using agents that act via physical mechanisms irrespective of whether or not they are inside of the cell. The Gendelman group has loaded MΦs with super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for imaging purposes [104], whereas the Baek and Hirschberg groups have loaded gold nanoshells into MΦs for photothermal therapies [110, 111]. Both of these applications take advantage of the trafficking aspect of MΦs to disease sites, but their effects are triggered by external sources, so they do not have to be released from the MΦ.

4.3 Genetically Engineered Macrophages

Perhaps the most exciting potential application of MΦs is the use of genetic engineering to augment existing MΦ behaviors or endow new functionalities [113]. Since MΦs are heavily implicated in inflammation, healing and general homeostatic maintenance in virtually all tissues [66], they are a logical cell type for the development of new genetically engineered therapeutics.

The failure of early trials which used ex vivo educated anti-tumor MΦs, might have been due to lack of MΦs trafficking into the tumor or to the plasticity of MΦs which would likely result in a rapid loss of the anti-tumor phenotype due to re-education from the tumor microenvironment [67–69]. Genetic engineering methods that can be used to enforce specific therapeutic behaviors are listed in Table 4. For instance, IFNβ is implicated in inhibiting angiogenesis in tumors by repressing pro-angiogenic (VEGF and MMP9) and homing receptor (CXCR4) genes in neutrophils [114]. IFNβ-deficient MΦs treated with exogenous IFNβ, upregulate genes (iNOS and IL-12b) associated with cytotoxic phenotypes [115]. Thus, sustained expression of IFNβ may enhance the cytotoxic activity of MΦs while also modulating the tumor microenvironment.

MΦs generated from an iPSC-derived myeloid line transfected to constitutively express IFNβ, were injected three times weekly, for three weeks (2×107 cells/dose) into the peritoneum of a SCID mouse with an intraperitoneal disseminated NUGC-4 human gastric tumor. This protocol significantly inhibit tumor growth, with an untreated tumor growing 5x over 14 days, whereas in the group treated with MΦ-IFNβ the tumor only doubled in size [116]. Importantly, treatment with unmodified iPSC-derived MΦs resulted in enhanced tumor growth of 10x over 14 days, indicating the unmodified cells are either pro-tumorigenic or the tumor is able to repurpose these MΦ into a pro-tumorigenic phenotype. A cytotoxic effect was also observed in vitro and IFNβ-expressing MΦs mediated more cytotoxicity than MΦs expressing IFNγ or TNFα, even though IFNγ or TNFα are generally regarded as more potent cytotoxic mediators. The authors indicated this outcome may reflect the reduced levels of expression of IFNγ or TNFα in the transduced MΦs due to the toxicity of high levels of IFNγ and TNFα.

Escobar et al. performed autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplants with selective expression of IFNα in TIE2+ tumor-associated MΦs in MMTV-PyMT, a spontaneous breast cancer mouse model, at 5.5 weeks [117]. Administration of IFNα has proven effective in solid and hematologic cancers though is limited due to high toxicity [118, 119]. However, the highly localized TIE2+-MΦ-mediated delivery of IFNα reduced lung metastatic areas 5-fold and primary tumor size 3-fold without apparent toxic effects [117].

Rather than attempting to change endogenous MΦ behavior, a number of investigators have modified MΦs to express therapeutic proteins [27, 28, 98, 107, 120–122]. For instance, P450 reductase, an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of the prodrug cyclophosphamide (CPA) into toxic metabolites, was inserted into CD14+ human monocytes using an adenovirus [120]. To further increase the specificity of P450 reductase expression in the hypoxic tumor, the expression was placed under the control of a synthetic hypoxia responsive promoter, OBHRE. A single intraperitoneal injection of 2×106 modified MΦs, followed by weekly intraperitoneal injections of CPA, in two different human ovarian carcinoma xenograft peritoneal models resulted in a doubling of median survival time (HU: 49 to 21 days, TOV21G: 106 to 56 days) when compared to mice treated with unmodified MΦs and CPA. A similar study was performed where intraperitoneally injected RAW264 cells stably transfected with intracellular rabbit carboxylesterase, a prodrug convertor for irinotecan to SN38, in a peritoneal Pan02 pancreatic tumor, was able to minimally increase mouse survival time by approximately 10% [122].

In an interesting application of MΦs or MΦ-like cell lines as bioreactors, RAW264 cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) [98, 107], catalase or luciferase [98]. The modified cells (5×106 cells in a single dose) were intravenously injected via tail vein into a Parkinson’s disease mouse model. In this mouse model, Parkinson’s-like pathology is induced by an intracranial injection of 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA), resulting in strong inflammation of the brain. Transfected RAW264 cells were found in the brain hemisphere injected with 6-OHDA up to 21 days post administration, and the respective protein transfected into RAW264 cells was found to be expressed. In the case of GDNF and catalase, neuron degeneration was reduced and neuroprotective behavioral effects were observed as quantified using rotarod and aphomorphine toxicity rotation tests [98, 107] when compared to unmodified RAW264 cells. Live animal imaging 30 days post transplantation with luciferase-expressing RAW264 cells revealed luciferase expression only in the brain, though it is not clear if this is arising from the transplanted RAW264 or other neuronal cells transfected by secreted exosomes from MΦs containing luciferase plasmid. Confocal microscopy on organ slices collected 1 and 5 days post transplantation revealed GFP-expressing RAW264 cells could be found in the lesioned hemisphere, spleen, lymph node and liver, with the number of GFP+ cells increasing in the lesioned hemisphere from day 1 to day 5 and decreasing in the other organs. Additionally, polarizing RAW264 cells towards an M2 phenotype using IL-4 further enhanced the neuroprotective effects, though it is not clear if this was due specifically to the M2 phenotype, an enhancement in cell survival or a change in MΦ trafficking to the brain.

GM-CSF, a growth factor for monocytes and MΦs, or components of its cognate receptor, has also been transduced into MΦs for two different applications. In the first, autologous or allogenic monocytes were purified from rabbit blood, transduced with adenovirus to express GM-CSF and differentiated into MΦs [121]. Transplantation of 3×107 autologous GM-CSF-MΦs or allogenic unmodified MΦs via an ear vein injection upstream of a post arterial ligation model in rabbits revealed augmented blood vessel growth. The authors found in the allogenic, but not the autologous, transplant of unmodified MΦs, inflammation was induced, leading to recruitment and heavy infiltration of endogenous monocytes into the affected areas which aided in arteriogenesis. While the autologous MΦs appeared to infiltrate, this was insufficient for therapeutic benefit. Autologous MΦs infected with GM-CSF adenovirus were able to mimic the effect observed using allogenic unmodified MΦs. The addition of GM-CSF was chosen to improve monocyte lifespan and because local injections of GM-CSF improve arteriogenesis [123].

The most exciting application of a MΦ-based therapy were reports of a treatment of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis [27, 28]. This condition occurs in mice due to the loss of the beta subunit of the GM-CSF receptor (Csf2rb). Loss of Csf2rb results in poor MΦ survival in the lungs, progressive accumulation of lung surfactant and eventual respiratory failure. Two groups, Happle and coworkers [27] and Suzuki and colleagues [28] demonstrated wildtype or Csf2rb-corrected MΦs instilled into the lung engrafted in the lungs, survived for at least 9 months and highly significantly, improved the survival of the Csf2rb−/− mice. This was suggested to be due to the survival advantage granted to the wildtype or gene-corrected MΦs by a functional GM-CSF receptor and an unoccupied MΦ niche due to the lack of other MΦs within the lung capable of competing for local GM-CSF. At one year post transplantation, Suzuki et al. show gene-corrected MΦs transplanted into Csf2rb−/− mice were able to self-renew to levels found in wildtype mice. Importantly, using histology and flow cytometry, Csf2rb−/− mice transplanted with GFP-labeled MΦs showed complete integration of transplanted MΦs throughout the intra-alveolar and interstitial spaces. Microarray analysis confirmed gene expression profiles of the alveolar MΦs in the transplanted and untreated wildtype mice were virtually indistinguishable. This is especially surprising because prior to transplantation, the gene-corrected MΦs isolated from bone marrow, are distinct from alveolar MΦs. The ability for transplanted MΦs to dynamically alter their phenotype to match the local tissue-resident MΦ lends further credence to the concept that local tissue microenvironments provide instructive signals which can shape the behavior of MΦs [66].

Genetically engineered MΦs have great potential and further modifications of MΦs to augment their behavior could form the basis of new therapies. For example, increasing GM-CSF or GM-CSF receptor expression may increase survival of transplanted MΦs in tissues beyond the lung [27, 28] or blood vessels [120]. As the development, identity and behavior of the many tissue resident MΦs are better understood, it may be possible to engineer MΦs ex vivo that migrate into and survive in specific organs after administration by activation of specific transcription factors [124, 125]. Phenotype plasticity may also be altered. For example, knocking out proteins in the NFκB pathway may lock polarization of MΦs in a cytotoxic M1 phenotype, as shown with IKKβ knock out macrophages adoptively transferred into an ID8 tumored mouse, where a M1 cytokine profile (IL-10, IL-12p70, TNFα) and differential expression of M1/M2 genes (IL-12p40 and arginase-1) were observed up to 14 days post transfer in tumor ascites and tumor associated macrophages, respectively [126, 127]. However, it should be noted that the tumor associated macrophages profiled for M1 genes may not necessarily be the cells adoptively transferred, as these could not be distinguished from the endogenous population. Overexpression of miR-222 in RAW264 cells co-injected with 4T1 breast tumor cells inhibited tumor growth by limiting MΦ chemotaxis and suppressing tumor growth by inhibiting the CXCL12-CXCR4 axis [128]. Inhibition of STAT3 by overexpression of STAT3β in tumor associated MΦs also suppressed tumor growth [129]. Proliferative capacities can be programmed into MΦs in a variety of means; Hoxb8 overexpression at the monocyte progenitor level results in a self-renewing capacity, whereupon loss of Hoxb8 results in MΦ differentiation [40]. It was recently discovered that transiently reduced expression of the MafB transcription factor activates a self-renewal program in tissue-resident MΦs [20, 130, 131]. This observation opens the door to controlled proliferation of MΦs in vivo, which may be necessary to induce high levels of engraftment. This could increase the potency of the treatment. With the advent of techniques like CRISPR-Cas9, engineered cell behaviors are closer to reality.

5. Pharmacokinetics and Biodistribution of Administered Macrophages in Animals

An important rationale for MΦ based cell therapy is that injected MΦs can migrate to the site of innate recruiting signals generated by inflammatory conditions. In this respect there is a paucity of studies that examine the fate of administered MΦs in a systematic and quantitative manner. In publications where MΦs are used as drug delivery vehicles and BD/PK of the drug is measured, there are slightly enhanced pharmacokinetics when drugs are packaged within MΦs. For example, the plasma half-life of catalase is increased from 2.5h to 3.3h following its delivery in a MΦ. Despite the small increase in PK, tissue AUC increased significantly by 2–3x depending on the organ [99]. This would be indicative of either drug release from MΦs or drug remaining in MΦs which have left the circulation and entered the tissue [99]. In the HIV anti-retroviral MΦ delivery study the biodistribution of indinavir, a small molecule HIV antiretroviral, showed significantly higher levels of drug within the: spleen, lung, liver and lymph nodes. Remarkably, the levels were stable over 10 days, further supporting the “drug depot” model, although it was not evident if the drug was in the original loaded MΦ or rather if the MΦ had been destroyed and the drug crystal had distributed to these organs after release from the MΦ [104].

The Choi and Baek groups have attempted to trace the trafficking of the MΦ by tracking the loaded material through histology. Iron oxide particles were loaded into MΦs prior to intravenous injection into a nude mouse bearing a xenograft human tumor, and iron oxide particles were detected in the tumor using Prussian blue staining 5 days post injection [106]. However, no other organs were evaluated, so it is unclear whether this was a specific trafficking effect. Moreover they did not demonstrate the iron oxide was in the original MΦs that were loaded with the iron. Loading of liposomal doxorubicin into MΦs showed a modest effect on reducing tumor growth, when compared to a similar dose of free liposomal doxorubicin [106] however here again, it was not clear if the liposomes were delivered by MΦs which had migrated into the tumor.

In another study, MΦs loaded with gold nanoshell particles were injected directly into the tumor. Histological analysis of the tumor for the gold nanoshells post photothermal therapy revealed the vast majority of gold remained immediately adjacent to the injection site as large aggregates, indicating minimal migration of the MΦ away from the injection site into the tumor [110]. Human monocytes loaded with gold nanoshells intravenously injected into nude mice with human MDA-MB-231 BR brain metastases were able to cross the blood brain barrier and co-localized with metastatic sites 24 hours post injection. To confirm the identity of human monocytes by histology, anti-human CD68 in conjunction with monocytes loaded with fluorescent microspheres were used [112]. In another qualitative study, intravenously injected luciferase transfected RAW264 MΦs followed by live animal imaging in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease have demonstrated trafficking of MΦs towards sites of inflammation [98], but it remains unclear how much of the initial MΦ successfully survives the injection process, migrates towards the brain and what (if any) off-target migration occurs.

In more quantitative studies demonstrating the use of gene corrected (CD131+) MΦs transplanted into the lungs of Csf2rb (CD131−)-deficient mice, engraftment and survival kinetics were evaluated by tracking the percentage of CD131+ cells in bronchoalveolar lavage as determined by flow cytometry. Over a period of 12 months, CD131+ cells rose from zero to 69% of bronchoalveolar lavage cells due to proliferation of the transplanted MΦs. Transgene specific PCR conducted at 1 year after transplantation showed transplant-derived cells present only in the lung, but not in blood, bone marrow or spleen [28]. In general, the reliance on histology for MΦ markers and/or tracking loaded materials to show presence of MΦs in various tissues has not resulted in a quantitative understanding of the effect of the route of administration on the time dependent persistence of injected MΦs in the blood or other tissues.

6. Overall Outlook - Potential Pitfalls and Opportunities

In our opinion, the field of MΦ-based therapies is emerging but several gaps in understanding need to be addressed for the field to progress as a cell based therapy (Table 5). Specifically there are needs for: 1) quantitative methods to evaluate the biodistribution, kinetics and survival after administration of live MΦs in an animal, 2) the use of explicitly defined primary MΦs rather than transformed cell lines in animal studies, 3) the extension of tactics developed in stem cell delivery fields to administer MΦs so that a high portion of injected cells survive the initial administration and 4) the use of niche generating methods to enhance MΦs engraftment.

Table 5.

General guidelines for the development of macrophage-based therapeutics:

|

First, over the last ten years, a series of groups have published results attempting to map the trafficking of transplanted cells. The vast majority of these studies label the MΦs with a fluorescent dye, radioactive marker or imaging particle that is tracked post transplantation. The results are often similar; the signal is first confined to the lung, then is observed to move to the liver and spleen, much like the results observed in the initial human trials and in studies using MSCs [57, 58, 132–134]. A significant concern is that these methods do not indicate the viability of the cell. All of these tracking materials can be transferred to other cells if the transplanted MΦ dies (especially highly phagocytic endogenous MΦs). Since the signal is not coupled with cell viability, one cannot be sure if living cells are tracked. If the MΦs die, signals that are observed would represent the trafficking of other cells or the normal metabolism of the marker.

In order to trace the efficacy of a cell-based therapy, it is critical to be able to accurately determine the trafficking and position of the viable transplanted cells. This can be accomplished using more techniques which track live cells [58, 132]. For example, luciferase or fluorescent protein activity is rapidly lost when not within a cell, so detection of these proteins can be used as a method to determine the viability of transplanted cells [135–137]. Due to the lack of PK/BD data on systems where signal is coupled directly to cell viability, the efficiency (percentage of administered cells that lodge in the target site and their survival time) and extent of engraftment has not been determined [78, 79, 81, 99, 100, 103, 104, 106, 110, 116, 120].

A related concern is the lack of quantitative analysis that is applied to the biodistribution of transplanted MΦs into other sites. Few studies report the percentage of dose or absolute number of cells that are observed in various organs, making it difficult to evaluate the engraftment efficiency in non-target sites. While it is understandable that certain techniques do not easily lend themselves to quantitation, the application of quantitative histological assessment using donor MΦ specific antibodies is required to indicate the presence of transplanted MΦs in the tissue of interest (i.e. Anti-human CD68 staining for human monocytes in a mouse background [112]). The number of stained MΦ profiles in multiple sections not only in the target organ but also in organs such as the spleen, liver and lung would improve the current understanding of where the injected cells go and how long they remain. Quantitation of cell biodistribution and survival provides essential information in determining paths forward for the development of MΦ therapies. For example, if therapeutic efficacy is observed, despite a very low number of engrafted cells, it may indicate the effect is not due to the engrafted cells but to a molecule secreted from the injected MΦs elsewhere in the body. An example of this behavior is reported in a myocardial infarction mouse model with intravenously injected MSCs that are mostly entrapped in the lungs. Entrapped MSCs in the lung secrete TSG-6, an anti-inflammatory protein that decreased the systemic inflammatory response, reduced infarct size and improved cardiac function [57]. As with other cell-based therapeutics, immune rejection is a possible concern. To our knowledge, these events have not occurred partly due to the use of autologous material, but may also be due to the lack of engraftment data or a robust means of tracking cell survival post injection.

Quantitative biodistribution studies coupled with gene expression profiling of the transplanted MΦs may provide guidance on why those cells were able to engraft, while the majority of the population was not. This information could direct the development of genetically modified lines with improved engraftment towards specific organs. Due to the lack of such data in the literature, these questions cannot yet be answered.

Second, the MΦs used in the reviewed publications are generated from a variety of sources using a number of different protocols. Ranging from cell lines (RAW264, THP-1), collection from blood, isolation from bone marrow, or spleen, the behaviors and phenotypes can vary widely. MΦ cell lines, while possessing many of the same characteristics, are nonetheless significantly different from primary MΦs. Compared to primary cells, cell line MΦs are exceptionally robust, requiring no extra growth factors for survival. This likely affects their trafficking and ability to engraft into other organs in ways that may be difficult to mimic using primary cells. While cell lines provide proof of concept information, the genetic differences between cell lines and primary cells may lead to misconceptions concerning survival and engraftment efficiency. Due to their replication potential, cell lines have a potential tumorigenicity or virus shedding that make them poor candidates for translation into the clinic.

Investigators should be very explicit in the methods section in their publications concerning the collection and differentiation protocols, including the animal strain, any pretreatments, age, anatomic source of precursor cells/monocytes/MΦs, culture conditions and cytokine treatment [43]. As mentioned earlier, changing the source of MΦs from spleen to bone marrow resulted in significant different results in a model of nephropathy [78, 79]. Specification of macrophage subtypes has also become incredibly complex over the last decade, and the M1/M2 paradigm is fading in favor of a more dynamic classification based upon describing the MΦ based on the full context of its’ origin and differentiation pathway, growth medium conditioning and gene expression profile [43, 69]. As a corollary, the behavior of MΦs post transplantation need also be studied. Suzuki et al. performed an outstanding characterization of the infused MΦs post transplantation, to establish that bone marrow derived MΦs are capable of adopting a lung-resident MΦ profile [28].

It is interesting to note that many studies utilized immunocompromised mice. Due to the lack of comparable data with immunocompetent mice, it is not clear what the effects using immunocompromised mice would have had on the outcome. Systematic studies that examine the multifaceted interactions between endogenous immune cells and transplanted MΦs in autologous models using a variety of immunocompromised mice should provide instructive and interesting results that may be applicable for developing effective therapies in humans using transplanted MΦs.

Third, the field of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) transplantation can provide guidance towards determining or increasing the trafficking, survival and tracking of transplanted MΦs [138, 139]. While in depth tracking studies of intravenously injected MΦs have yet to be performed, the results in MSC transplantation mimic some aspects of the results observed in the human clinical trials of MΦ cell therapy. Intravenous injection of 5×105 fluorescent DsRed-expressing MSCs radiolabeled with Cr-51 demonstrated a distinct separation of detectable viable fluorescent protein and radiolabel in the blood, lungs, liver, spleen, kidneys and bone marrow. The majority of Cr-51 signal was detected in the lungs one hour after administration, followed by migration of the signal to the liver at 24h. The presence of live MSCs was determined by culturing cell suspensions generated from organs collected at 5 min, 1, 24, or 72h for up to 7 days and identification of DsRed+ MSCs by fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry for CD44, a MSC-specific marker. In contrast to the radiolabel measurements, live MSCs were detected only up to 24h in the lungs, and were not found in other organs examined at any other time points [58]. This differential observed between live cell and radioactivity signals was hypothesized to be radioactive cell debris undergoing liver clearance. Repeating similar experiments in immunodeficient mice lacking NK, T and B cells or an ischemia-reperfusion liver injury model did not alter these results, indicating an adaptive immune response was not responsible for loss of HSCs nor did a strong inflammatory signal recruit HSCs to the liver [58]. This study showed MSCs injected intravenously are short-lived and viable MSCs cannot be detected beyond the lungs 24h post injection. Similar experiments tracking transplanted MSCs have also shown the majority of MSCs to be trapped in the lungs [132–134, 140].

MSC entrapment in the lungs may be due to the size of cultured MSCs (∼20 µm diameter), which exceed the diameter of pulmonary capillaries [132]. Ge and coworkers by fractionating MSCs into small (∼18 µm) and large (∼30 µm) cells, showed that when injected into intra-internal carotid artery considerably higher rates of infarct in the brain when larger MSCs were injected [141]. Whereas 3D cultured HSCs were uniformly smaller (∼13 µm) and did not induce infarcts in the brain. MΦs are approximately 20–30 µm in diameter, placing them within the range for lung entrapment. Culturing MΦs in 3D cultures or pretreatment with osmotic agents to temporarily shrink MΦs [142–145] prior to injection may reduce overall cell size and prevent entrapment in the lung. Reduced rates of injection (0.2 mL/min compared to >1mL/min) of MSCs into the carotid artery of rats have also reduced the risk of stroke [146]. The Heilshorn lab has shown that packaging multiple cell types in a hydrogel or protein engineered scaffold with growth factors may also protect from injection stress induced cell death [147, 148] and increase long term survival, as seen with dorsal subcutaneous transplantation of adipose-derived stem cells in nude mice [149] and intramuscular transplantation of stem cell derived endothelial cells in an ischemic hind limb mouse model [150].

Pretreatment of transplanted cells has been employed in attempts to reduce lung entrapment and/or increase cell survival [59, 138, 139]. Fischer and colleagues blocked adhesion of MSCs to endothelial cells by inactivation of the VCAM-1 counter-ligand (CD49d) on MSCs and administered the MSCs in two boluses. This modestly improved the passage of MSC through the lung from ∼0.15% to 0.3% [133]. Cardiomyocytes derived from embryonic stem cells treated using a combinations of methods (including heat shock, matrigel co-injection, ZVAD-fmk2 (caspase inhibitor), IGF-1 (Akt pathway activator), Bcl-XL (blocks cell death), cyclosporine A (attenuates mitochondrial death) and pinacidil (mimics ischemic preconditioning)) lead to better engraftment post-injection in an ischemic heart [151]. These types of pretreatments may help to identify potential druggable targets that may increase overall survival of injected MΦs [152]. However, in viewing the totality of the data, it appears that the diameter and deformability of the transplanted cellsmay be the most important parameters that impact transit beyond the lung and survival after injection.

Finally, preparation of the host for transplantation can also be performed to enhance engraftment and survival of transplanted cells. Vasodilation using sodium nitroprusside reduces lung entrapment in HSC transplantation [153]. Tissue MΦs also occupy specific niches, and removal of endogenous MΦs from these niches may open them for newly transplanted MΦs. As mentioned previously, gene-corrected MΦs were able to engraft and adopt lung-specific MΦ markers in lungs lacking alveolar MΦs [27, 28]. Liposomal clodronate can specifically deplete MΦ subsets in various organs depending on route of administration [154] and potentially creates tissue MΦ niches available for newly transplanted MΦs.

7. Conclusions

In conclusion, MΦ based therapies have focused on disease models with an extensive inflammation component, including: cancer, nephropathy and Parkinson’s [78, 97, 99, 100, 102–104, 106, 120]. In these studies various approaches were used: ex vivo MΦs alone, as delivery vehicles for drugs, nanomaterials and enzymes or gene modified therapeutic MΦs. The most successful MΦs based therapy to date, in regard to repair of function and duration, is an alveolar MΦ replacement therapy in the lung [27, 28]. To build upon this success in other diseases, quantitative biodistribution studies should be conducted, clearly defined primary MΦs should be used and improved survival and engraftment strategies will need to be employed to optimize efficacy. Success should allow MΦ based therapeutics to expand into other inflammatory MΦ rich conditions such as: chronic infectious diseases, lysosomal storage diseases, diabetes, spinal cord injury, stroke and arthritis. While the recruiting of MΦs via inflammation follows certain canonical molecular pathways, each of these conditions are unique in their pathology and may respond differently to MΦ cell-based therapy. Tumors are able to hijack MΦs to aid in their survival and expansion, and many of these characteristics which promote cancer may be beneficially exploited in applications for regenerative medicine. Ultimately, the versatility and plasticity of MΦs represent both an opportunity and a research challenge for the future development of MΦ cell therapeutics. Controlling the MΦ may bring us closer to achieving the original goals of curing cancer [4] but in the journey to do this, we may come to realize that MΦ based therapies in regenerative medicine, lysosomal storage disorders or infectious diseases have a greater health impact.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NIH R21-CA182703. S.L. is supported by a National Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Doctoral Postgraduate Scholarship. A.D. is supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program and NIH T32 GM007175.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Learoyd P. National Blood Service. Leeds Blood Centre; 2006. A Short History of Blood Transfusion. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacerna LV, Jr, Stevenson GW, Stevenson HC. Adoptive cancer immunotherapy utilizing lymphokine activated killer cells and gamma interferon activated killer monocytes. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1988;38:453–465. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(88)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill S, June CH. Going viral: chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy for hematological malignancies. Immunological reviews. 2015;263:68–89. doi: 10.1111/imr.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]