Abstract

Facial asymmetry is one of the commonest facial anomalies, with reported incidence as high as 34%. Hemifacial microsomia (HFM) has an incidence of 1 in every 4000–5600 children and is one of the commonest causes of facial asymmetry. The standard treatment of HFM is orthognathic surgery by bilateral saggital split osteotomy (BSSO) or distraction osteogenesis (DO) of the mandible, both of which involve prolonged periods of occlusal adjustments by an orthodontist. Here, we present distraction of the mandible by means of a novel modified step osteotomy to correct the facial asymmetry in a case of hemifacial microsomia without disturbing the occlusion. This novel technique can prove to be a new tool in the maxillofacial surgeons armamentarium to treat facial asymmetry.

Keywords: Hemifacial microsomia (HFM), Bilateral saggital split osteotomy (BSSO), Distraction osteogenesis (DO), Novel step osteotomy, Genioplasty

1. Introduction

Facial asymmetry is one of the commonest facial anomalies, with a reported incidence as high as 34%.1 It may be the manifestation of any amongst a constellation of congenital or acquired craniofacial anomalies. Apart from the problems with facial aesthetics, speech and mastication, it is also responsible for the social anguish in the patient. Often, it is the patient's only reason to seek treatment.

Hemifacial microsomia (HFM) is the commonest congenital craniofacial anomaly, after cleft lip and palate, with an incidence of 1 in every 4000 to 5600 children2, 3 leading to facial asymmetry. It presents with hypoplasia of five major craniofacial components, the ear (most consistent finding), mandible (most commonly involved skeletal structure), orbit, facial nerve and facial soft tissues, including the muscles of mastication. HFM is mostly unilateral; however, bilateral involvement may also occur.

Facial asymmetry has historically been treated by two principal treatment modalities, orthognathic surgery or distraction osteogenesis. Both of these techniques have their own inherent advantages and shortcomings. However, the clear advantage of distraction over orthognathic surgery is its ability to provide better soft tissue response, theoretically leading to lesser chances and lower magnitude of relapse.4

Additionally, for the application of the principles of distraction, osteotomy cuts can be modified to allow selective movements for deformity correction without affecting the occlusion. This eliminates the lengthy and meticulous process of orthodontic management, which was otherwise involved pre- and post-surgery in these patients.

We present here a novel step osteotomy for distraction of the inferior border of the ramus and body of the mandible with a unidirectional distractor for correction of facial symmetry avoiding any occlusal changes.

2. Case description

2.1. Clinical findings

An otherwise healthy 20-year-old male reported to our outpatient clinic for the correction of his facial deformity, with the chief complaint of facial asymmetry, which had undergone worsening with increasing age due to lack of growth on the right side of the face. The patient however did not report any difficulty in breathing.

On clinical examination, the patient revealed bilaterally malformed auricles with absence of patent external auditory meatus. The eyes were normal, but the right malar eminence was hypoplastic. Also, there was a disfigured right body and ramus of mandible (Fig. 1), along with a rudimentary masseter on palpation. The masseter muscle on the contralateral side was hypertrophied, with bowing of the lower border of the mandible (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Frontal view of the patient.

Fig. 2.

Profile photographs of the patient.

Severe soft tissue deficit was visible on the right side of the face. However, bilateral TMJ movements were palpable.

Intra-oral examination revealed an Angle's class III occlusion on the left side along with ipsilateral anterior open bite and an occlusal cant with clockwise rotation of the occlusal plane viewed in the frontal plane. The occlusion on the right side could not be assessed due to the absence of lower first molar; however, there was a class II canine relation. He was diagnosed as a case with hemifacial microsomia (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Intra-oral view of the patient.

2.2. Radiographic findings

Radiographic evaluation on OPG showed a hypoplastic hemimandible of the right side with vertical deficiency of the right body and ramus of the mandible. The right temporo-mandibular joint appeared to be rudimentary with absence of the normal deep concavity of the glenoid fossa and protuberance of the articular eminence that can be easily appreciated on the normal contralateral side (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Orthopantomograph of the patient.

Based on the clinical findings, the patient's deformity can be classified as Type IIA hemifacial microsomia according the classification provided by Pruzansky and co-workers.

There was a discrepancy of 1.5 cm in the height of the right ramus of the mandible compared to the normal side.

2.3. Reconstructive challenges

The reconstructive challenge in this patient laid in augmentation of the skeletal sub-structure on the right side of the face to bring it at par with the structures on the opposite side, along with a Le Forte I osteotomy with down fracture of the right maxilla for correction of the occlusal cant followed by augmentation of soft tissue of the involved side to provide satisfactory fullness of the soft tissue contour of the patient.

He also required correction of his occlusal discrepancy by means of initial dental decompensation persurgically followed by final orthodontic alignment post-surgically. As he was satisfied with his alignment of teeth, and uninterested in getting any correction of his occlusion, the final treatment planned for him was a sort of skeletal camouflage involving vertical distraction osteogenesis of the right body and ramus of the mandible by means of a novel “step osteotomy” to avoid any changes in occlusion. Augmentation of hard and soft tissue was planned using dermal fat post-distraction, for final correction and to provide clinically acceptable soft tissue contour.

Even with the absence of a patent external auditory meatus, the patient was satisfied with his hearing and desired no correction for the same, nor did he want auricular reconstruction.

2.4. Operative procedure

Under general anaesthesia, the patient was prepared and draped, keeping the neck extended so as to allow easy identification of bony landmarks.

A standard sub-mandibular (Risdon's) incision was placed, and layer-wise dissection was done to reach the lower border on the mandible. The pterygo-masseteric sling was sharply incised at the angle of the mandible and the buccal cortical surface of the mandible was skeletonised in the vicinity of the angle region.

Osteotomy was planned in the following manner. First, a horizontal cut was carried forward from the posterior border at the mid-ramus level anteriorly, up to just behind the lingula. The cut was then carried in an anterior-inferior direction so as to avoid the point of entry of the inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle. This was followed by a cut running anteriorly till the level of the first molar tooth, parallel to the lower border of the mandible. Then the osteotomy was completed by an oblique cut through the lower border of the mandible (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A diagrammatic representation of the “modified stepped osteotomy” outlined on a normal mandible.

It was crucial to avoid the point of entry of the inferior neurovascular bundle, and also the apices of the mandibular posterior molars.

The osteotomy was outlined by means of an oscillating saw and cuts were carried down to the lingual cortex without carrying it through the lingual cortex, so as to avoid unnecessary trauma to the lingual soft tissues.

This was followed by placement of the distractor with fixation of the screws on either side of the osteotomy. The osteotomy was now completed my means of fine sharp osteotomes with extreme caution and the distractor was checked for activation (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Distractor placement after completion of osteotomy.

The activating arm of the distractor was extruded through a separate skin incision and then closure was done layer-wise.

Inter-maxillary fixation was unnecessary, but the patient was put on soft diet to avoid chances of fracture through the weakened angle of mandible.

Following a latency period of 6 days, activation of the device was done twice per day in 0.5 mm increments for 15 days, after which the device was left in place for three months for consolidation.

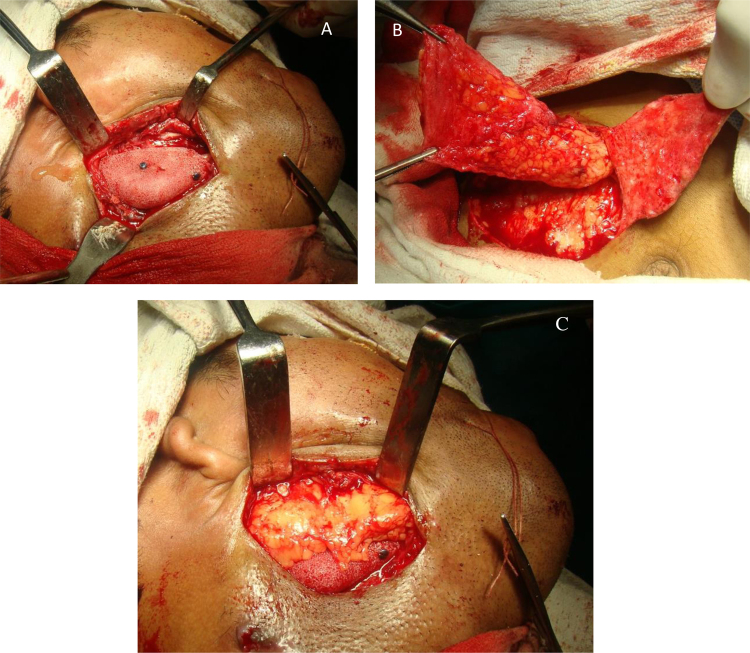

After consolidation, the patient was recalled again for distractor removal. Exposure of the surgical site revealed good bone formation and increased bone stock in the angle and body region. In the same setting, the angle region (original osteotomised segment of bone that was distracted) was augmented with medpore fixed by the help of two titanium screws and sub-dermal fat was harvested from the abdomen and used to provide soft tissue contour (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

(A) Medpore augmentation of angle of mandible. (B) Harvesting of dermal fat. (C) Fat augmentation of the angle of mandible.

Additionally, lateral sliding genioplasty was done through an anterior de-gloving approach to correct the deviated chin (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Lateral sliding genioplasty.

The 1-month postop photograph of the patient shows considerable improvement of facial aesthetics and clinically acceptable correction of facial asymmetry (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

One-month postoperative photograph of the patient.

3. Discussion

The treatment of HFM is complex and the results can be unstable if the reconstructive challenges are not anticipated or accounted for. The major problem of these patients is the unnatural appearance of the face caused by the hypoplastic bony skeleton, deficiency of soft tissue on the involved side and many a times co-existent hypertrophy of structures on the opposite side. They may also present with occlusal derangements along with an occlusal cant, and cross-bites leading to temporo-mandibular joint derangements.

A variety of approaches may be used to treat HFM. One of the cornerstones of decision making regarding maxillofacial reconstruction of HMF lies in the presence of a functional TMJ complex. Since the patient in question had a functional TMJ (Type IIA), reconstruction of the same is not indicated.5

In younger patients with mild deformity, residual growth maybe utilised by means of a functional appliance to bring about a more favourable mandibular position coupled with orthodontic supra-eruption of maxillary teeth.

From their excellent review of the available literature as well as from clinical experience, Posnick and co-workers concluded that the greatest benefit is availed for the patient if the deformity is corrected by a definitive single-stage surgery during the stage of early skeletal maturity.5

In Type I and IIA HMF, if patient's growth is complete (as was the case with our patient), a bilateral saggital split osteotomy (BSSO) can be done to bring about asymmetric advancement or setback or both to correct mandibular asymmetry, along with a bilateral Le Forte-I (LF-I) osteotomy for correction of occlusal cant. Additionally, a genioplasty may be necessary to correct chin asymmetry.5

Alternatively, distraction osteogenesis (DO) may be applied to increase the mandibular body as well as ramus length to achieve forward and downward movement of the mandible to achieve an open bite on the affected side, which can be later closed by orthodontically assisted supra-eruption on the maxillary teeth.

There is no significant difference between orthognathic surgery and DO as far as stability, relapse or post-intervention neurosensory disturbance is concerned.6, 7, 8 Hence, these parameters cannot be the basis of decision making while choosing DO over orthognathic surgery. The claimed advantage of DO is better soft tissue response. However, DO causes much more discomfort to the patient and requires additional surgery for distractor removal.

In the patient in question however all of these standard treatment options were rendered unviable due to the unwillingness of the patient to have his occlusal relation tampered with. As such, a modified step osteotomy was designed that would allow lengthening of the ramus as well as deposition of bone in the inferior aspect of the body of the mandible keeping the occlusion undisturbed.

Distractional bone augmentation of the mandible bypassing the tooth-bearing segment was earlier reported by Gunaseelan et al.,9 who performed an extended genioplasty up to the mandibular first molar with a step modification in the region of the mental foramen. This segment was then distracted by means of an external pin-fixated distraction device. The authors used this along with inter-positional arthroplasty and bilateral coronoidectomy to correct OSAS in an adult patient with TMJ ankylosis.

A similar, albeit extended, osteotomy was reported by Shang et al.10 who performed a modified internal mandibular distraction osteogenesis without altering the pre-existing occlusion in a patient of micrognathia and OSAS secondary to TMJ ankylosis.

In our experience, there has been no earlier report of a similar step osteotomy in the angle-body region bypassing the occlusal segment, as was done in this case.

In conclusion, we can say that the modified step osteotomy described in this paper could be a predictable, stable, economical and less time-consuming alternative treatment for patients of mild to moderate hemifacial microsomia.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Severt T.R., Proffit W.R. The prevalence of facial asymmetry in the dentofacial deformities population at the University of North Carolina. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1997;12(3):171–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grabb W.C. The first and second branchial arch syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965;36(4):85–508. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poswillo D. The pathogenesis of the first and second branchial arch syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1973;35:302–328. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(73)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehrotra D., Vishwakarma K., Chellapa A.L., Mahajan N. Pre-arthroplasty simultaneous maxillomandibular distraction osteogenesis for the correction of post-ankylotic dentofacial deformities. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Posnick J.C. Elsevier; China: 2014. Principles and Practice of Orthognathic Surgery. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baas E.M., Pijpe J., de Lange J. Long term stability of mandibular advancement procedures: bilateral sagittal split osteotomy versus distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41:137–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baas E.M., de Lange J., Horsthuis R.B.G. Evaluation of alveolar nerve function after surgical lengthening of the mandible by a bilateral sagittal split osteotomy or distraction osteogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baas E.M., Bierenbroodspot F., de Lange J. Bilateral sagittal split osteotomy versus distraction osteogenesis of the mandible: a randomized clinical trial. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:180–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunaseelan R., Anantanarayanan P., Veerabahu M., Vikraman B. Simultaneous genial distraction and interposition arthroplasty for management of sleep apnoea associated with temporomandibular joint ankylosis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;36:845–848. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shang H., Xue Y., Liu Y., Zhao J., He L. Modified internal mandibular distraction osteogenesis in the treatment of micrognathia secondary to temporomandibular joint ankylosis: 4-year follow-up of a case. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012;40:373–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]