Abstract

Dens invaginatus is a developmental anomaly resulting in an infolding of the enamel organ into the dental papilla prior to calcification of the dental tissues. The invagination predisposes the tooth for the development of dental caries. Conventional radiographs do not provide detailed information concerning the three-dimensional image, which would help the clinician in making a confirmatory diagnosis and planning the treatment before undertaking the actual treatment. This report describes a case where Oehlers type II dens invaginatus was diagnosed with the help of spiral computed tomography. The locations of the primary root canal and the invagination were assessed from spiral computed tomography scan images. Usually, the invagination is present on palatal/lingual side. However, in this case, the invagination was unusually located on labial side, which has yet not been reported. The tooth also showed certain unusual morphological features.

Keywords: Anomaly, Dens invaginatus, Resolution, Spiral computed tomography

1. Introduction

Developmental disturbances of teeth present a challenge to the clinician in diagnosis and treatment in view of their complex morphology. Dens invaginatus is a developmental anomaly that results in an enamel-lined cavity intruding into the crown or root before the mineralization phase.1

The etiology of this anomaly is still unclear. Most commonly affected tooth is the permanent maxillary lateral incisor. The reported incidence varies from 0.04% to 10%.2 It has been classified by Oehlers into three types, namely Type I, II and III.3

The clinical presentation of dens invaginatus varies from deep cingulum pit to a deep infolding reaching the apical foramen.2 Clinical significance of dens invaginatus lies in the increased risk of caries and pulpal pathosis.2

This article describes the successful diagnosis and management of unusual type II dens invaginatus with ‘labial’ invagination with the help of spiral computed tomography scan.

2. Case report

A 24-year-old Indian male described an episode of recent severe throbbing pain in maxillary left lateral incisor over the past 4 days; there was no previous history of any symptoms.

Examination of the dentition revealed a peg-shaped maxillary left lateral incisor. There was no decay or discoloration in relation to maxillary left lateral incisor.

The labial surface showed a small cusp-like elevation on the mesial half with a semilunar groove. The incisal surface showed a groove extending mesiodistally and a small pit. The palatal surface was smooth and rounded, without any groove or pit (Fig. 1).

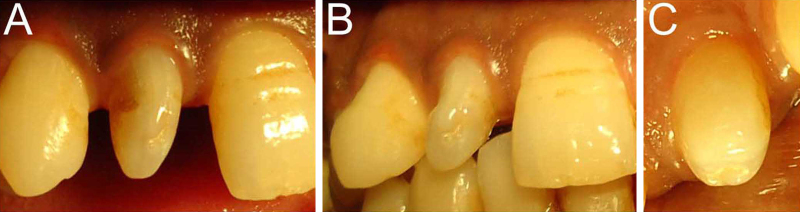

Fig. 1.

(A) and (B) The preoperative intraoral photographs showing peg-shaped maxillary left lateral incisor with cusp-like elevation and semilunar groove on labial surface. (C) Smooth, rounded palatal surface and incisal groove.

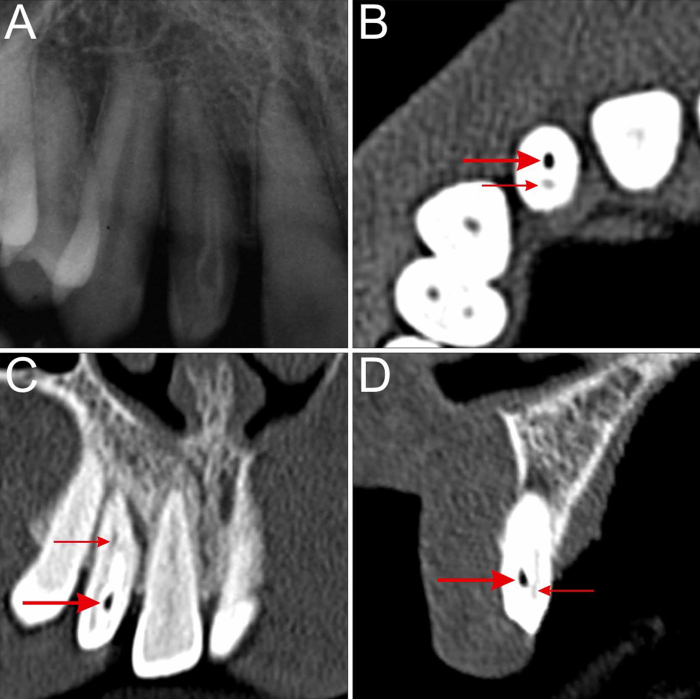

The intraoral periapical radiograph showed an invagination in the crown extending to the junction of coronal and middle 1/3rd of the root, suggestive of Oehlers Type II dens invaginatus (Fig. 2A). There was no family history of similar dental findings.

Fig. 2.

(A) Intraoral periapical radiograph suggestive of Oehlers Type II dens invaginatus. (B) Axial, (C) Coronal and (D) Sagittal spiral computed tomography scan images showing relative positions of the invagination (labially) and main root canal (palatally) [Larger arrow indicating the invagination and the smaller one indicating the main root canal].

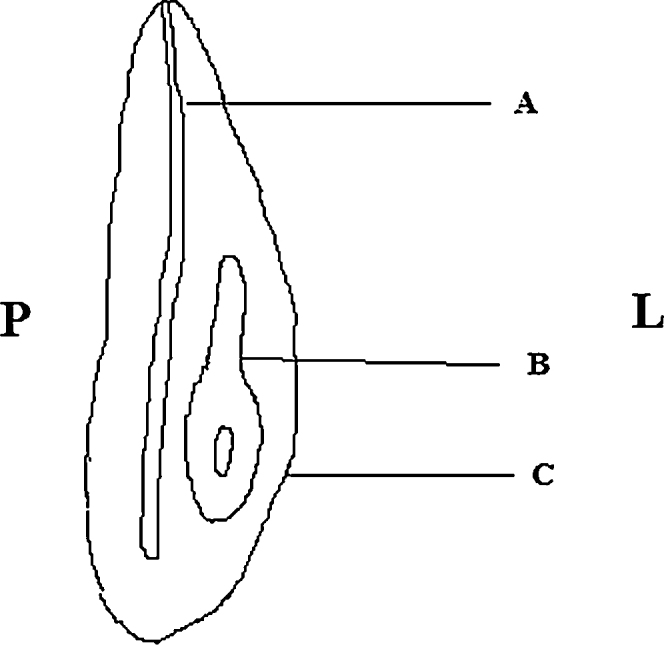

For further accurate diagnosis and to evaluate the position of the invagination relative to the main canal, spiral computed tomography scan of the area of interest was performed. It revealed an invagination extending to the middle third of the root as a blind sac. It also showed the relative positions of the main root canal and the invagination. Coronal and sagittal spiral computed tomography scan images clearly showed that the invagination was located on labial side. The orifice of the main canal was located palatally and orifice of the invagination was placed mesiolabial to it (Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Diagrammatic representation of coronal spiral computed tomography scan image. A – Main root canal, B – Invagination, C – Cusp-like elevation, L – Labial side, and P – Palatal side.

Following isolation of the tooth with a rubber dam, the pulp chamber was opened and the invagination orifice located first. The main root canal was discovered distopalatally to the invagination orifice. Root canal treatment of the tooth was completed (Fig. 4). The patient experienced no postoperative discomfort and was subsequently referred for appropriate coronal restoration.

Fig. 4.

Post-operative intraoral periapical radiograph.

3. Discussion

Various diagnostic imaging techniques aid in the diagnosis and treatment planning of developmental anomalies. Conventional radiographs compress three-dimensional anatomy into a two-dimensional image, thereby limiting its diagnostic value.

Conventional two-dimensional radiographs may provide inadequate diagnostic information for the clinician to appreciate the complex anatomy of dens invaginatus, which may lead to its inappropriate treatment.4

Computed tomography is an imaging technique that generates three-dimensional images of an object from a large series of two-dimensional radiographic images.5 Spiral computed tomography presents a large volume of data instantly, thus allowing faster examination.6

The advent of cone beam computed tomography has led to its extensive use for the diagnosis of oral and maxillofacial diseases. The major advantages of cone beam computed tomography over spiral computed tomography are the reduced radiation exposure and a superior image quality.7 However, spiral computed tomography scan was used for the diagnosis of present case due to unavailability of cone beam computed tomography in the city at the time when patient reported.

The spiral computed tomography scan images were useful in assessing the true nature of the invagination, in particular, the relationship of the invagination with primary root canal. This not only helped in definitive diagnosis, but also in treatment planning. The locations of the primary root canal and the invagination, as assessed from spiral computed tomography scan images, helped in designing the access cavity, thus conserving the tooth structure.

By definition, the invagination is present on ‘palatal/lingual’ side in dens invaginatus. However, in the present case, as confirmed from spiral computed tomography scan and clinically, the invagination was present on the ‘labial’ side. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of dens invaginatus with invagination on ‘labial’ side.

Typically, dens invaginatus presents with a deep invagination in the lingual pit area which may be difficult to recognize clinically. Cases with peg-shaped lateral incisor often show the pit at the tip of crown.8 Atypical location and morphology of lingual pit may suggest presence of dens invaginatus. However, in the present case, the palatal surface was smooth, without any groove or pit. Other unusual morphological features in this case included cusp-like elevation on the labial surface and an incisal groove. It may be hypothesized that the invagination was contained within the cusp-like elevation on the labial surface.

Generally, the invagination originates in a deep folding of the foramen caecum during odontogenesis. It may less commonly originate from the incisal edge of the tooth.9 In the present case, the invagination may have its origin in the semilunar groove on the labial surface. Another possibility is that the invagination originated in the incisal groove and pit. The coronal and sagittal spiral computed tomography scan images support the first possibility.

The possibility of presence of infected pulpal tissues in inaccessible parts of the root canal system complicates the endodontic treatment of teeth with dens invaginatus.10 The success of treatment depends on the ability to gain access to, clean and shape the root canal.

In conclusion, the invagination may rarely occur on ‘labial’ side. The presence of unusual morphological features like elevation, bulge or groove on the labial surface may indicate dens invaginatus with ‘labial’ invagination. The treatment of teeth with dens invaginatus should be based on a thorough clinical and radiographic evaluation. Spiral computed tomography scan images are useful for diagnosis as well as treatment planning of dens invaginatus.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Yeh S.C., Lin Y.T., Lu S.Y. Dens invaginatus in the maxillary lateral incisor treatment of 3 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;87:628–631. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(99)70146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaramillo A., Fernández R., Villa P. Endodontic treatment of dens invaginatus: a 5-year follow-up. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;101:e15–e21. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hülsmann M. Dens invaginatus: aetiology, classification, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment considerations. Int Endod J. 1997;30(2):79–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2591.1997.00065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White S.C., Pharaoh M.J. 6th ed. Mosby; St Louis, Missouri: 2009. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguiar C.M., Ferreira J.P., Câmara A.C., de Figueiredo J.A. Type 2 dens invaginatus in a maxillary lateral incisor: a case report of a conventional endodontic treatment. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2008;33(2):17–20. doi: 10.17796/jcpd.33.2.d2k2368275n06682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silberman A., Cohenca N., Simon J.H. Anatomical redesign for the treatment of dens invaginatus type III with open apexes: a literature review and case presentation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(2):180–185. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel S. New dimensions in endodontic imaging: part 2. Cone beam computed tomography. Int Endod J. 2009;42(6):463–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sapp J.P., Eversole L.R., Wysocki G.P. 6th ed. Mosby; St Louis, Missouri: 2004. Contemporary Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiménez-Rubio A., Segura J.J., Jiménez-Planas A., Llamas R. Multiple dens invaginatus affecting maxillary lateral incisors and a supernumerary tooth. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1997;13(4):196–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-9657.1997.tb00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decurcio D.A., Silva J.A., Decurcio R.A., Silva R.G., Pécora J.D. Influence of cone beam computed tomography on dens invaginatus treatment planning. Dental Press Endod. 2011;1(1):87–93. [Google Scholar]