Abstract

Protein kinases regulate numerous cellular processes, including cell growth, metabolism and cell death. Because the primary sequence and the three-dimensional structure of many kinases are highly similar, the development of selective inhibitors for only one kinase is challenging. Furthermore, many protein kinases are pleiotropic, mediating diverse and sometimes even opposing functions by phosphorylating multiple protein substrates. Here, we set up to develop an inhibitor of a selective protein kinase phosphorylation of only one of its substrates. Focusing on the pleiotropic delta protein kinase C (δPKC), we used a rational approach to identify a distal docking site on δPKC for its substrate, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK). We reasoned that an inhibitor of PDK’s docking should selectively inhibit the phosphorylation of only PDK without affecting phosphorylation of the other δPKC substrates. Our approach identified a selective inhibitor of PDK docking to δPKC with an in vitro Kd of ~50 nM and reducing cardiac injury IC50 of ~5 nM. This inhibitor, which did not affect the phosphorylation of other δPKC substrates even at 1 µM, demonstrated that PDK phosphorylation alone is critical for δPKC-mediated injury by heart attack. The approach we describe is likely applicable for the identification of other substrate-specific kinase inhibitors.

Graphical Abstract

INTORDUCTION

The protein kinases super family accounts for approximately 2% of the eukaryotic genes and about 518 protein kinases are predicted in the human kinome.1 Protein kinases catalyzed phosphorylation, the transfer of the γ-phosphoryl group from adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to the hydroxyl group of defined amino acid, which regulated many biological processes, including metabolism, transcription, cell cycle progression, and differentiation. Phosphorylation is the most widespread type of post-translational modification in signal transduction with over 500,000 potential phosphorylation sites for any given kinase in the human proteome and 25,000 phosphorylation events described for 7,000 human proteins.2,3 Phosphorylation is mediated by the catalytic domain that consists of a small N-terminal lobe of β-sheets, a larger C-terminal lobe of α-helices, and the ATP binding site in a cleft between the two lobes.4 Many kinase inhibitors target the highly conserved ATP-binding pocket.5 However, since the catalytic domain of most eukaryotic kinases is structurally similar, developing specific protein kinase inhibitors that target the conserved ATP-binding pocket in a selective manner is a challenge and targeting different sites in addition to the conserved ATP-binding site to increase selectivity is a promising approach.

One way to achieve specificity between a kinase and specific substrate involves interactions between docking motifs on the substrate with interaction domains on the kinase, termed docking site. The interaction site between the substrate and the kinase involves a binding surface for the substrate that is distinct from the catalytic active site on the kinase, and a binding surface on the substrate that is separated from the phosphorylation motif that is chemically modified by the kinase.2,6 Distinct docking sites were identified for different substrates and these sites do not compromise the stereochemical requirements for efficient catalysis by the kinase’s active site.7 Docking has been characterized for a number of protein kinase families, including c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs), A cyclin-dependent kinase complex (CDKC), and Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases.8–15 For example, Lee et al. identified a six amino acid substrate-docking site on the C-terminal Src kinase (Csk), and a peptide mimicking the docking site inhibits Csk phosphorylation of Src (IC50 = 21 µM), but only moderately inhibits its general kinase activity.16

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a multigene family of related serine/threonine kinases that regulates many cellular processes, including cell cycle, homeostatic control, stress-response and programmed cell death.17 There are ten different isozymes within the PKC family, divided into three subfamilies according to the nature of their regulatory domain. All PKCs are comprise of a C-terminal catalytic domain that is very similar between the different isozymes, linked through a variable domain to a regulatory domain, which is highly divergent between the different isozymes. The uniqueness of the regulatory domains of each PKC, mainly at the C2 domains, has a critical role for the specific activity of each isozyme. Each PKC isozyme phosphorylates multiple protein substrates and selectivity is achieved in part by their subcellular location and the mode of their activation.18–20 Previously, we developed inhibitors of protein-protein interactions that elucidated the functions of each PKC isozyme. These inhibitors are 6–10 amino acids long peptides that mimic part of one surface of the interacting proteins, thereby inhibiting the resulting signaling pathways of the given PKC isozyme, in a highly specific manner.21,22 The ability to modulate PKC signaling in an isozyme-specific manner provided an advantage over the isozyme non-selective PKC inhibitors.23 However, each PKC isozyme phosphorylates many different substrates in the same cell.24 A tool that will selectively inhibit the phosphorylation of one substrate at a time will be highly valuable in identifying how the PKC isozyme regulates a particular function.

δPKC, cloned over 25 years ago,25 is a pleiotropic kinase that phosphorylates many protein substrates, including heat shock protein 27 (HSP),26 myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS),27 signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT),28 glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH),29 Troponin I30 and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK).31 The importance of δPKC signaling was demonstrated in several models of human diseases, such as cancer,32 stroke,33 sepsis,34 diabetes,35,36 neurodegenerative diseases37,38 and ischemic heart disease (heart attack).39,40 Previously, a correlation between δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation and cell death following cardiac ischemia was demonstrated.31 However, since δPKC phosphorylates many substrates, whether PDK phosphorylation mediates cardiac injury directly could not be determined.

Using a rational design, we developed a pharmacological tool to selectively inhibit only δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation. We developed peptide corresponding to the PDK substrate docking site on δPKC, ψPDK peptide. ψPDK peptide, derived from the regulatory C2 domain of δPKC, selectively inhibited δPKC-mediated phosphorylation of only PDK, without affecting the phosphorylation of other δPKC substrates under the same conditions. We demonstrated that ψPDK effectively minimized cardiac injury induced by ischemic event ex vivo and in vivo. Thus, kinase-substrate selective interactions can be useful drug targets, and our rational approach can help identify them.

Results and Discussion

Rational design of an inhibitor of PDK phosphorylation by δPKC

Mitochondrial PDK phosphorylation and activation by δPKC following cardiac ischemia correlates with a large infarct size and inhibition of δPKC reduces cardiac injury.31 However, in addition to PDK, many other substrates are phosphorylated by the pleiotropic enzyme δPKC. To determine if inhibition of PDK phosphorylation alone is sufficient to prevent cardiac injury we developed a selective inhibitor of δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation. To develop such a PDK-selective inhibitor, we reasoned that in addition to binding of δPKC’s catalytic site to the phosphoacceptor site on PDK, a selective PDK-docking site secures the anchoring of this substrate to δPKC. Such substrate docking sites were previously described for some other kinases.2

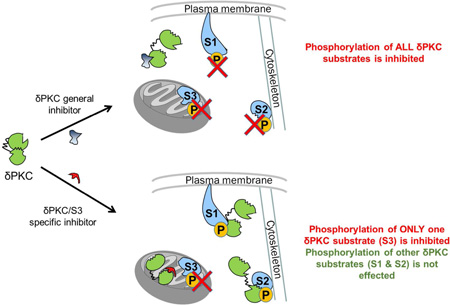

We hypothesized that PDK binding to δPKC should occur only after δPKC activation, and when δPKC is inactive, its PDK-docking site may be occupied by a pseudo-PDK (ψPDK) site, a PDK-like sequence that mimics the δPKC-binding site on PDK (Figure 1A). However, following δPKC activation, a conformational change in δPKC will dissociate the PDK docking site from the ψPDK site, and will expose the PDK docking site, making it available for protein interaction between the kinase and the substrate (Figure 1A, right panel). A similar concept led to the identification of a pseudo-phosphorylation sequence on many kinases that mimics the phosphoacceptor sequence on substrates.41 Since a peptide corresponding to pseudosubstrate is a competitive phosphorylation inhibitor of all the substrates of a given kinase, a peptide corresponding to the ψPDK site should selectively inhibit only the PDK docking and phosphorylation (Figure 1B). However, this peptide should not affect the binding of other δPKC substrates (e.g., substrate XX; Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Development of an inhibitor that selectively inhibits only one substrate phosphorylation. (A) An inhibitor that selectively inhibiting the docking and phosphorylation of PDK by the multi-substrate (pleiotropic) kinase, δPKC. Intramolecular interactions within δPKC are disrupted by PKC activation, exposing the catalytic site as well as selective substrate-docking sites (red arrow, shown are docking sites for PDK and substrate XX on δPKC). Docking of these substrates to the kinase, concomitantly or one substrate at a time, increases the access of the catalytic site for the substrates, leading to their phosphorylation (P). In the inactive δPKC (left), the PDK-docking site interacts with a PKC sequence, ψPDK site, which mimics the kinase-docking site on PDK (blue). (B) A peptide corresponding to this ψPDK site is a competitive inhibitor for docking to and phosphorylation of PDK by δPKC, without affecting docking and phosphorylation of other δPKC substrates (e.g., substrate XX).

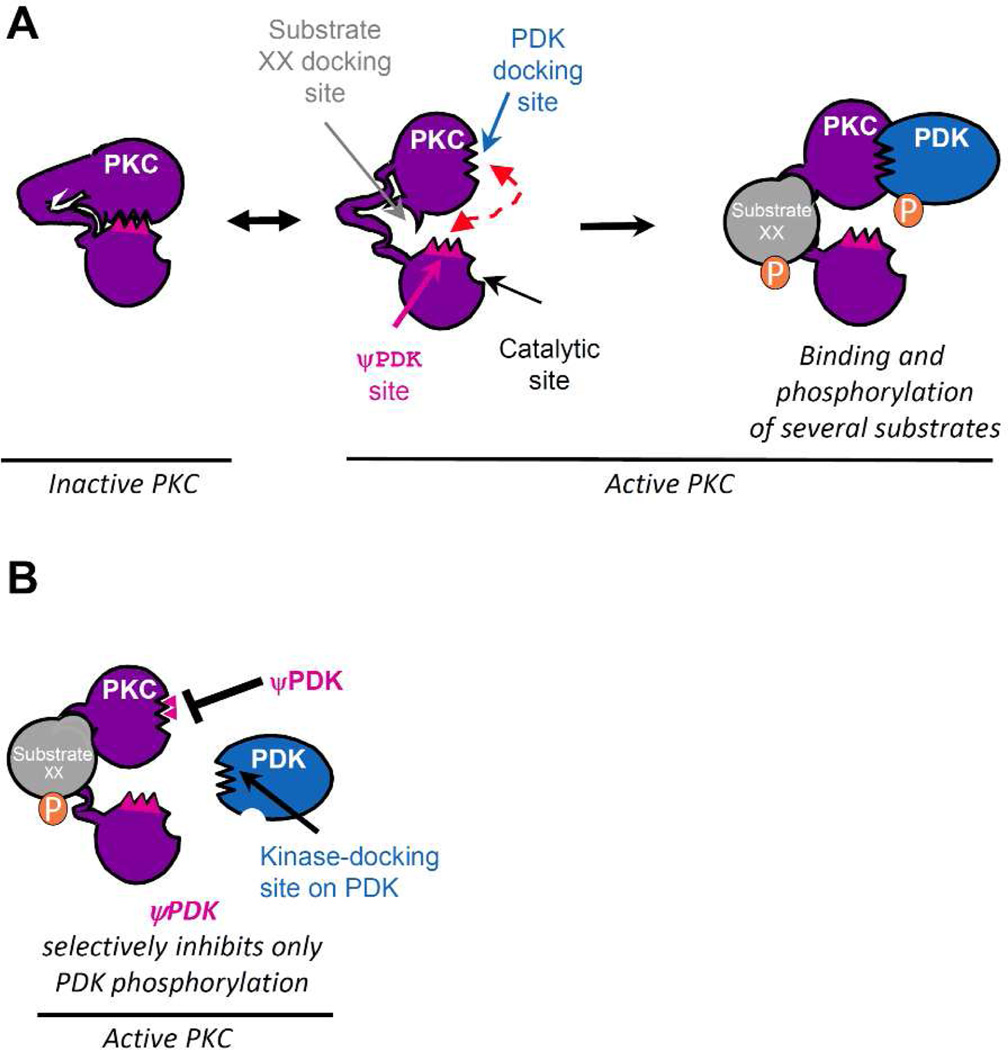

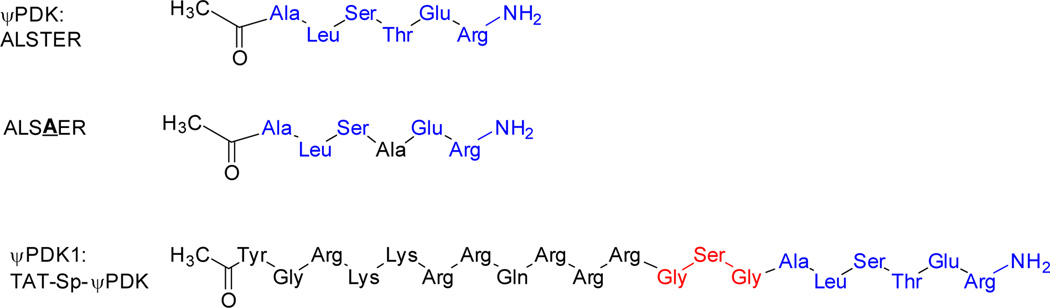

Using Lalign, we searched for a PDK-like sequence in δPKC and identified ALSTE (δPKC36–40), which is highly similar to ALSTD in the four isoforms of PDK (PDK391–395; Figure 2A–C). We reasoned that if the ALSTE/D sequence is required for PDK docking and phosphorylation by δPKC, it should be conserved across species. Indeed, ALSTE/D is conserved in both δPKC and PDK, in the species that have δPKC (Figure 2D–E). Importantly, in species that lack δPKC, the PDK sequence is missing altogether (e.g., worm and yeast; Figure 2F). The ALSTE/D sequence is also found in a number of other human proteins (Figure 2G). However, this sequence was only 100% conserved in PDK and δPKC across species (Figure 2G, arrows), suggesting that ALSTE/D is functionally important only in δPKC and PDK. ALSTE is also absent from other novel PKC isozymes (Figure 2H–I), together suggesting a selective role for ALSTE/D (the ψPDK site) for δPKC and PDK interaction. Note that if the overall sequence similarity between the kinase and its substrate is high, it will be challenging to identify a selective docking site using the method described here. Nevertheless, since there are many examples of kinases and substrates with low homology between them, this method will likely be of general use.

Figure 2.

Rational design of an inhibitor of PDK phosphorylation by δPKC. (A) Sequence alignment of human δPKC and PDK identified a short sequence of homology, ALSTE/ALSTD. (B) ALSTD in PDK (PDB: 1JM6) and ALSTE in the C2 domain of δPKC (PDB: 1BDY) are exposed and are available for protein-protein interactions (see colored structures). (C) Conservation of ALSTD sequence in the four PDK isoforms. (D) Conservation of ALSTE sequence in δPKC and (E) conservation of ALSTD in PDK in a variety of species. (F) Lack of ALSTD conservation in orthologs of PDK in worm or yeast, species that lack δPKC. (G) ALSTE/ALSTD sequences are found in 39 human proteins. Heat-map of the ALSTE/D conservation in orthologs of these proteins shows ALSTE/D conservation only in PDK and δPKC. Note that although three proteins (EPHA4 (Ephrin type-A receptor 4), Nek8 (Never in mitosis A-related Kinase 8) and UBIAD1 (Transitional Epithelial Response Protein 1) exhibit at least 4/5 amino acids similarity to ALSTE/D in multiple species, all 5 amino acids are conserved only in PDK and δPKC and a non-homologous substitution of any one amino acid in ALSTE/D is sufficient to cause a loss of activity of this peptide (Figure 5G). (Further information about all the proteins in Supplementary Table 1). (H) and (I), ALSTE sequence is not present in the C2 domains of other member of the novel PKC isozymes, εPKC and θPKC, to which δPKC belongs.39 (J) The ѱPDK site, ALSTE (including the adjacent R; see below), in the C2 domain of δPKC (PDB: 1BDY). * denotes identity and ^ denotes homology

Activity and selectivity of ψPDK peptide in vitro

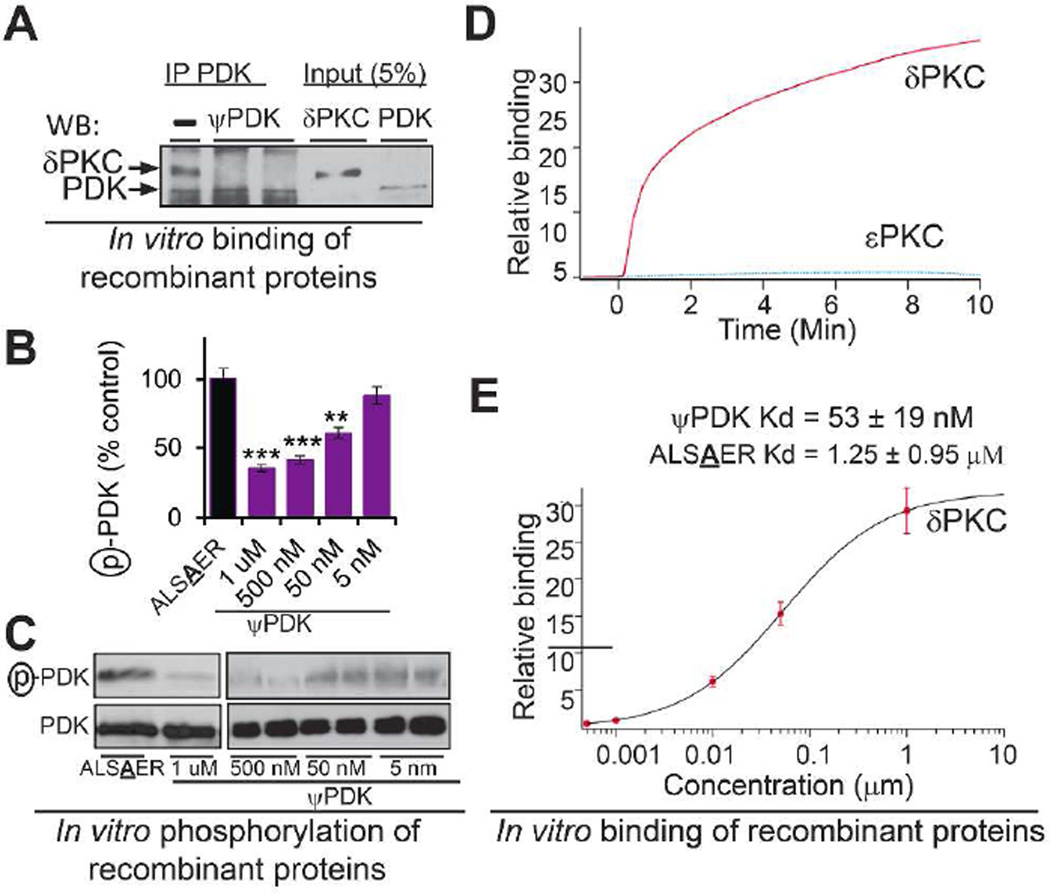

We synthesized a peptide corresponding to ψPDK site in δPKC (Chart 1, Supplementary Scheme 1 and Supplementary Table 2 for peptide characterization) and including an additional amino acid from δPKC (ALSTER, Figure 2J), because several peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions that we identified previously are at least six amino acid long.21,22 ψPDK peptide blocked δPKC binding to PDK, as determined by inhibition of co-immunoprecipitation (Figure 3A), and inhibited δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation by over 65%, in vitro as compared to ψPDK analog with the Thr changed to an Ala (ALSAER, Chart 1; Figure 3B–C). However ψPDK peptide did not affect the phosphorylation of other δPKC substrates, such as GAPDH (Supplementary Figure 1). Next, we determined δPKC binding to ψPDK in vitro. δPKC bound to ψPDK peptide in vitro in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3D) with Kd of 53±19 nM (Figure 3E); εPKC, another novel PKC isozyme, did not binds to ψPDK under the same experimental conditions (Figure 3D). There was a significantly higher Kd measured for the ψPDK analog with Thr changed to Ala (ALSAER, Chart 1), which was 1.25 µM or about 25 folds higher Kd for δPKC than ψPDK.

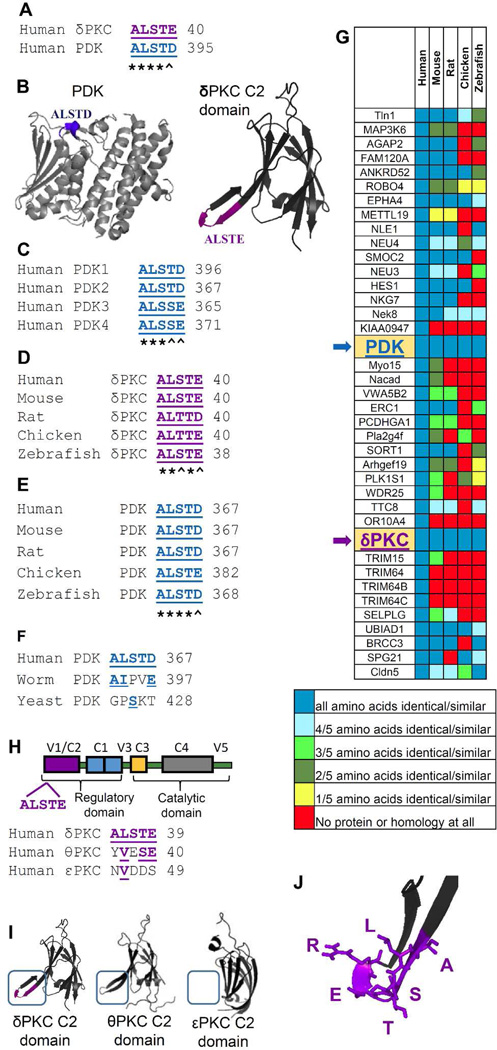

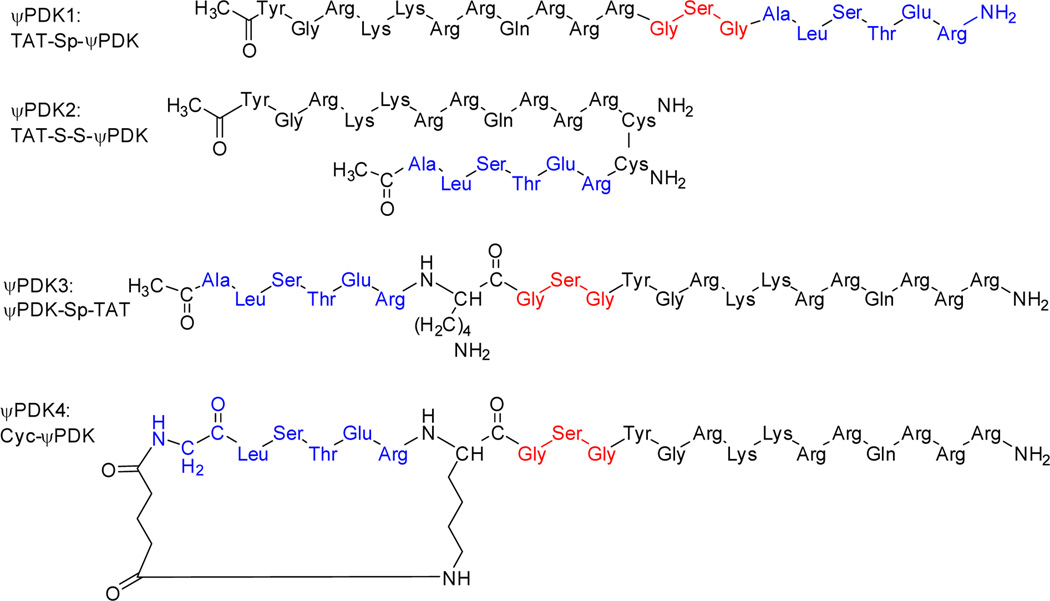

Chart 1.

Chemical structure of the ψPDK, ψPDK analog and ψPDK1 peptides. ψPDK peptide, an analog of ψPDK with an Ala substitution for the Thr (ALSAER) and ψPDK with TAT47–57 carrier peptide, using GSG as a spacer (ψPDK1).

Figure 3.

Activity and selectivity of ψPDK peptide in vitro. (A) ψPDK (1 µM) inhibited PDK/δPKC interaction in vitro, determined by co-precipitation and Western blot analysis (n=3). (B, C) δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation in vitro was inhibited by ψPDK (5 mM - 1 µM) relative to control peptide analog of ψPDK, in which one amino acid (Thr) was changed for an alanine (ALSAER) (n=3). (D) Binding curves of δPKC and εPKC, at ~ 75 µg/mL (~1 µM), to ψPDK peptide. ψPDK selectivity binds to δPKC as compared with another novel PKC, εPKC. (E) Binding assay of increasing amounts of δPKC to ψPDK or to ALSAER, an analog of ψPDK, in which one amino acid (Thr) was substituted for an alanine. ψPDK selectivity binds to δPKC (IC50 = 53 nM) compared with ALSAER (IC50 = 1.25 µM). Data presented as mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.005 compared to TAT control.

Selectivity of ψPDK1 peptide for δPKC substrates ex vivo

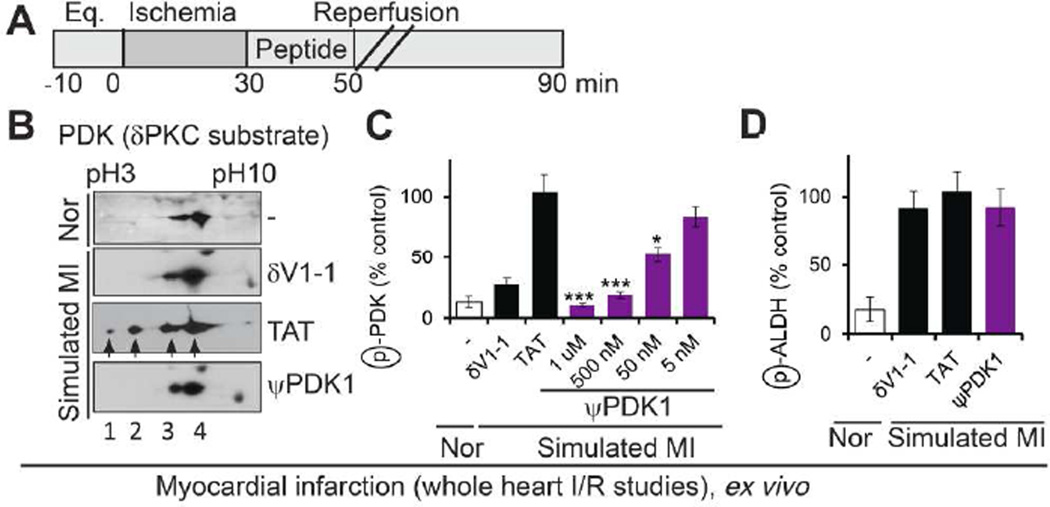

To test the biological activity of ψPDK, the peptide was conjugated to the TAT-derived cell permeating peptide (ψPDK1, Chart 1 and Supplementary Scheme 1 and Supplementary Table 2 for peptide characterization), TAT47–57,42 which enables safe and effective delivery of peptides into cells in culture, in vivo43,44 and even in humans.45–49 We next determined the effect of ψPDK1 peptide in a model of myocardial infarction, in which an intact perfused and beating heart is subjected to no-flow (ischemia) followed by reperfusion, as an ex vivo model of heart attack. Using this model of ischemic attack (ischemia/reperfusion), we found that ψPDK1 completely inhibited ischemia/reperfusion-induced increase in phosphorylation of PDK (Figure 4B–C). This effect was similar to δV1-1 effect (Figure 4B–C), which inhibits translocation and access of δPKC to all its substrates.39 (Note that two dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) allows the separation of PDK phosphorylation states from the lowest, spot 4, to the highest, spot 1 Figure 4B). Quantitation of spots 1 and 2 is provided in Figure 4C. For the analysis, we focused on spots 1 and 2, because only these two spots were inhibited by δPKC phosphorylation, as seen when using the general δPKC inhibitor, δV1-1; PDK basal level of phosphorylation (spots 3 and 4) are not mediated by δPKC). PDK activation leads to phosphorylation and inhibition of the mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), thus inhibiting ATP generation by the mitochondria.50 As expected, ψPDK1 treatment inhibited PDK activation, as demonstrated by inhibition of PDH phosphorylation (Supplementary Figure 2). To determine whether ψPDK1 inhibition was selective for δPKC-mediated phosphorylation inside the mitochondria, we also examined the phosphorylation state of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), an εPKC-selective mitochondrial substrate.51 As expected for isozyme-specific peptide inhibitor, ψPDK1 peptide did not affect ALDH2 phosphorylation (Figure 4D), demonstrating the selective effect of ψPDK1 for δPKC-mediated phosphorylation.

Figure 4.

ψPDK1 peptide selectivity for δPKC substrates; measurement in whole heart subjected to simulated myocardial infarction ex vivo. (A) Protocol of myocardial infarction model using isolated hearts subjected to ischemia and reperfusion (a model of simulated myocardial infarction; MI) or normoxia (Nor). Bars indicate the length (in minutes) of each treatment (eq = equilibration). Rat hearts were subjected to 30 min ischemia followed by 60 min reperfusion without or with peptide treatment for the first 20 minutes only. (B) Phosphorylation of PDK in heart extracts after ischemia and reperfusion in the presence of ψPDK1 or control peptide (1 µM). (C) Dose-dependent effect of ψPDK1 peptide treatment on the phosphorylation of PDK spots 1 and 2 (B) is expressed as percent change from phosphorylation in the presence of control peptide, TAT, (n=6). (D) As a further indication for the selectivity of ψPDK1 peptide, we showed that phosphorylation of another mitochondrial protein, aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), that is also phosphorylated under ischemic conditions,51 was unaffected by ψPDK1 peptide treatment (n=4). Data presented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, ***p<0.005 compared to TAT control.

It is formally possible that a given substrate uses the same interface to interact with and be phosphorylated by several different protein kinases and thus a protein-protein interaction substrate inhibitor identified by our method may affect more than one kinase of that substrate. This possibility could not be examined directly for PDK and ѱPDK, as the identity of the other PDK kinase is not known. Nevertheless, our data in Figure 4 demonstrate that only the δPKC-dependent phosphorylation (δV1-1 sensitive spots, 1 and 2) were also inhibited by ѱPDK. Spots 3 and 4, which are product of phosphorylation by another kinase, were not inhibited by ѱPDK treatment, suggesting that the above possibility is unlikely, at least for this protein-protein interaction.

Treatment with ψPDK1 at reperfusion (after the ischemic period) decreases cardiac injury

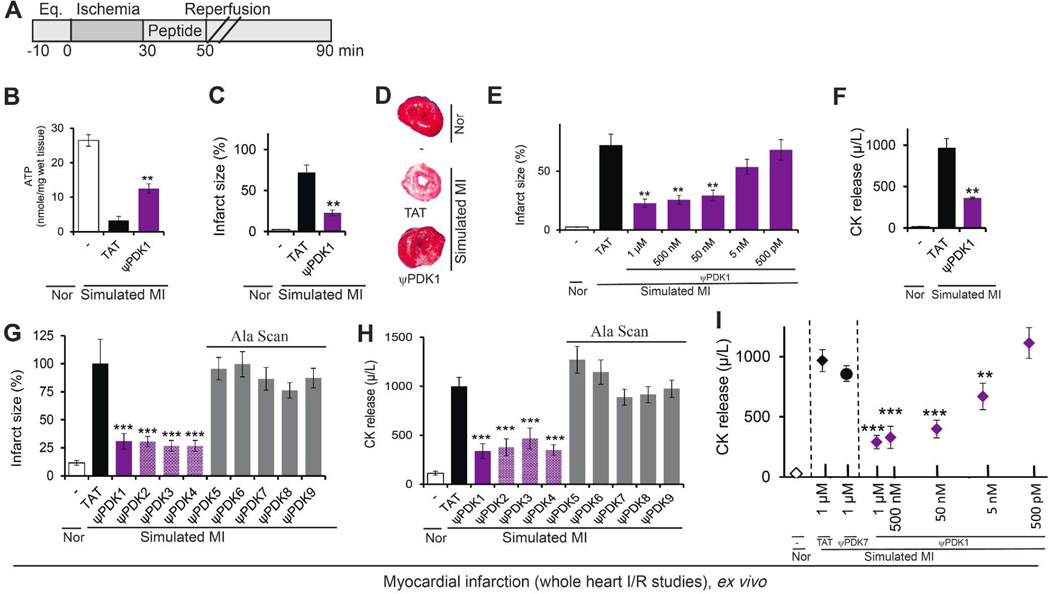

As discussed above, PDK phosphorylation inhibits PDH, thus shutting down ATP generation through the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. As expected, and using the above model of heart attack ex vivo (Figure 5A). ψPDK1, which inhibits δPKC-mediated PDK phosphorylation (Figure 4B–C), increased ATP levels (Figure 5B). Following ischemia and reperfusion ATP levels were ~15% of the levels under normoxic conditions and following treatment with ψPDK1, ATP levels increased by three folds (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

ψPDK1 peptide cardioprotective activity and structure activity studies; measurement in whole heart subjected to simulated myocardial infarction ex vivo. (A) Protocol of myocardial infarction model using isolated hearts subjected to ischemia and reperfusion (a model of simulated myocardial infarction; MI) or normoxia (Nor). Bars indicate the length (in minutes) of each treatment (eq = equilibration). Rat hearts were subjected to 30 min ischemia followed by 60 min reperfusion without or with peptide treatment for the first 20 minutes only. (B) Protection from myocardial injury was determined by analyses of the levels of tissue ATP, expressed as nmol ATP per cardiac wet weight (n=3); (C, D) 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining (red indicates live tissue and white – dead; n=6/hearts per treatment), and (E) Dose-dependent effect of ψPDK1 peptide treatment on TTC staining. (F) Protection from myocardial injury was determined by analyses of the levels of release of CK (n=6). Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. We tested the effect of the relative positions of the cargo (ALSTER) and the carrier (TAT), on the bioactivity. Protection from myocardial injury was determined by infarct size and CK levels following simulated myocardial infarction (G–H, purple columns). We also performed alanine scanning of ψPDK1 demonstrated that substitution of any of the amino acids with alanine (A) caused a reduction or a complete loss of bioactivity (G–H, grey columns) (n=6 hearts per treatment). (I) Dose-dependent effect of ψPDK1 peptide treatment on total CK release following simulated MI during 30-minute reperfusion demonstrates an IC50 of ~5 nM, (n=6 hearts/dose). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p<0.01, ***p<0.005 compared to TAT control.

Importantly, ψPDK1 treatment decreased infarct size by ~70%, as compared to treatment with control peptides when delivered only during reperfusion (Figure 5C–E). ψPDK1 treatment also decreased the levels of creatine kinase release (CK; Figure 5F), a marker that used extensively as an indication for myocardial damage in heart attacks in humans, as well as reduced levels of JNK phosphorylation, a marker of cell death (Supplementary Figure 3).

Structure activity relationship (SAR) studies

There was no significant change in activity of ψPDK1 when the cargo was linked at the C-terminus of TAT (ψPDK1), or at the N-terminus of TAT (ψPDK3) as one polypeptide. In addition, there was no difference in activity if the cargo was conjugated to TAT by disulfide- bridge (ψPDK2). In some cases cyclization can improve the bioactivity properties of linear peptides, here we tested one cyclic peptide (ψPDK4) with preliminary linker, which also did not improved the bioactivity of the linear peptide (ψPDK1). (Figure 5G–H for peptide structure see Chart 2 and Supplementary Table 2 for peptide characterization). In addition, we determined the contribution of all the amino acids of ψPDK to the biological activity of this peptide using Ala scan of the cargo by substituting each amino acid with an alanine. Confirming our binding studies (Figure 3E), we found that changing the Thr (ALSAER) or any other amino acid with an alanine abolished the biological activity of the peptide (Figure 5G–H, ψPDK5–9; for peptide structure see Supplementary Chart 1 and Supplementary Table 2 for peptide characterization). This supports our results examining evolutionary conservation of this sequence (Figure 2G). A dose-response study demonstrated that ψPDK1 is highly active; the IC50 for ψPDK1 peptide effect in reducing cardiac injury ex vivo was ~5 nM (Figure 5I), as measured by cardiac CK release, a clinical biomarker for heart attack.

Chart 2.

Chemical structure of the ψPDK1 peptide analogous. The peptides are comprised of: TAT47–57, a short positively charged peptide that is used as a carrier for the delivery of the peptides into the cell (black); a spacer, composed of three amino acids used as spacers between TAT and the cargo (red); and the cargo (blue). Cyclic peptide analog with conformational constraints was also prepared; this analog have the same amino acids as the linear peptide with extra alkyl chains that were used for cyclization.

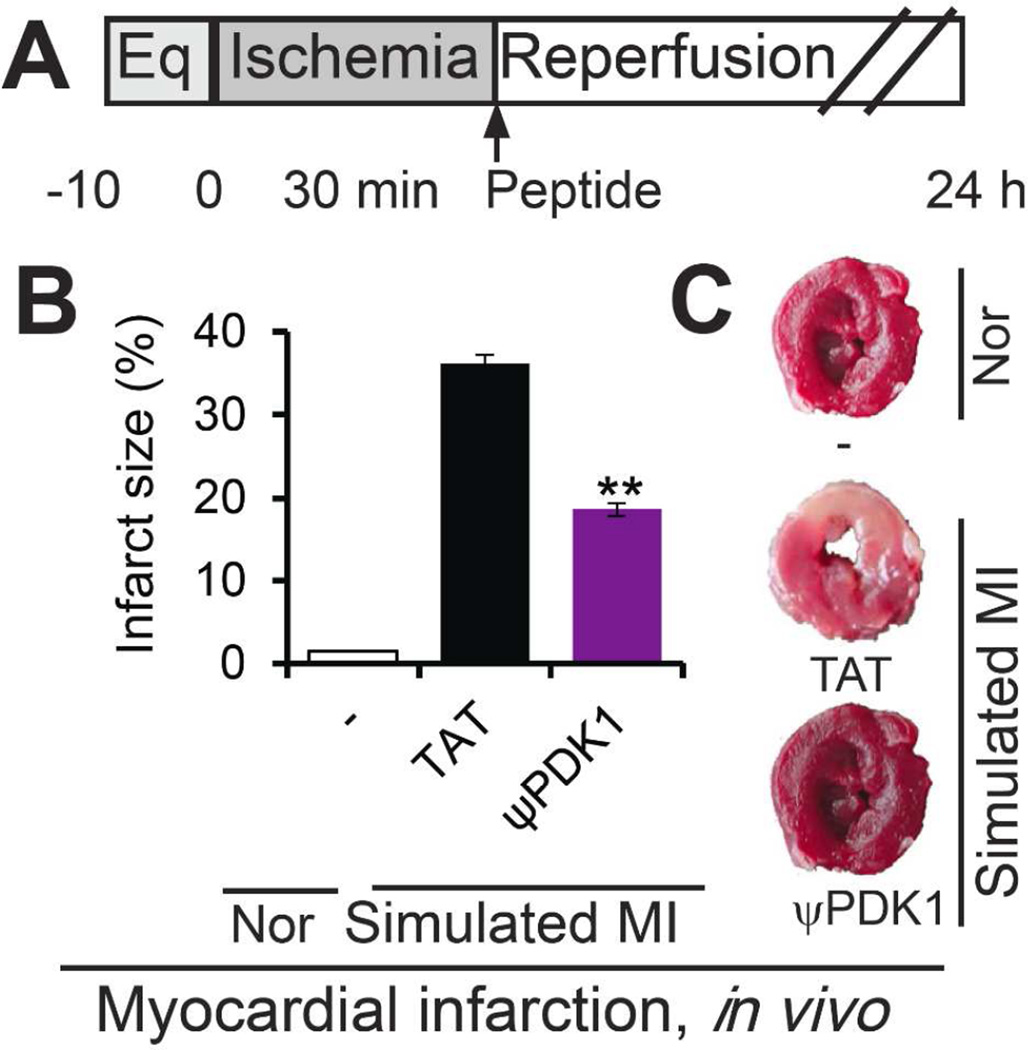

Cardioprotective effect of ψPDK1 peptide in vivo

Treatment with ψPDK1 peptide (2 mg/kg) in vivo, immediately after 30 minutes ischemia reduced infarct size by ~50% (Figure 6B–C), indicating the efficacy of the peptide.

Figure 6.

Activity of ψPDK1 peptide in vivo. (A) Protocol of myocardial infarction model in vivo. Rats were subjected to 30 min ischemia and 24 hours reperfusion without or with peptide treatment (2 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection). Shown are the effects of ψPDK1 and TAT control peptides on infarct size (n=6) (B), and examples of TTC staining (C). Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **p<0.01 compared to TAT control.

We also confirmed that ψPDK1 is safe. A six weeks sustained treatment of mice with 2 mg/Kg/day by implanting an osmotic pumps subcutaneously on their back, which provide slow and sustained delivery of the peptide,52 caused no changes in behavior, weight gain and other toxicity measures (Supplemental Figure 4).

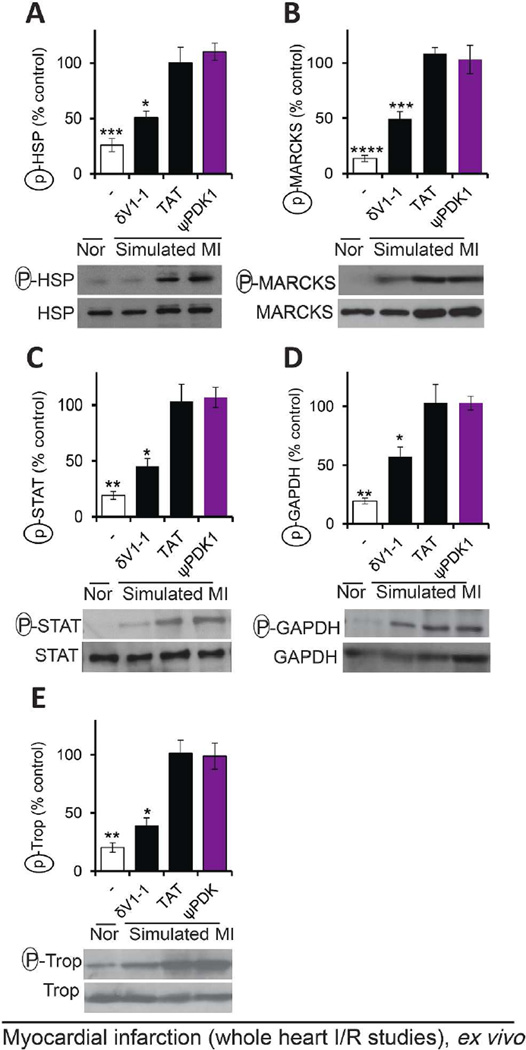

Selectivity of ψPDK1 peptide for different δPKC substrates ex vivo

Since δPKC is a pleiotropic kinase, phosphorylating many protein substrates,53 we next determined the selectivity of ψPDK1 peptide for PDK phosphorylation by measuring the phosphorylation of five other δPKC substrates. At 1 µM, a concentration that is 200 fold higher than its IC50 (Figure 5I), ψPDK1 peptide inhibited the phosphorylation of PDK (Figure 4B–C), but not the phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 (HSP),26 myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS),27 signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT),28 glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)29 and troponin I30 (Figure 7A–E). These data demonstrate the high specificity of ψPDK1 as a selective inhibitor of only one substrate of δPKC, the phosphorylation of PDK.

Figure 7.

Selectivity of ψPDK1 peptide as an inhibitor of PDK phosphorylation; phosphorylation of five other δPKC substrates following simulated myocardial infarction were not inhibited. Phosphorylation of HSP27 (A), MARCKS (B), STAT (C), GAPDH (D) or troponin I (E) in heart extracts after ischemia and reperfusion in the presence of control or ψPDK1 peptide (1 µM). Phosphorylation is expressed as percent change from control (TAT)-treated hearts. Data are representative of at least four independent experiments and presented as mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005, ****p<0.001 compared to ψPDK1 peptide-treated hearts.

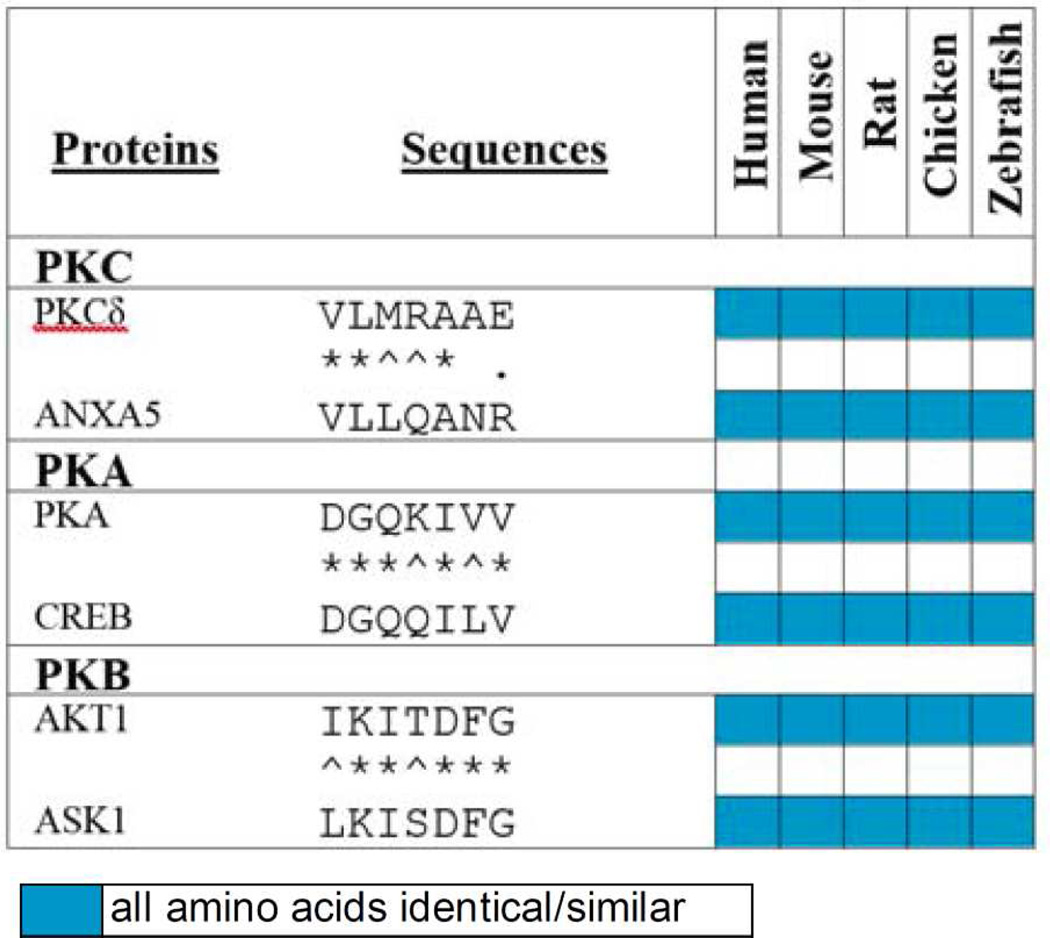

Finally, as most protein kinases have pleiotropic roles by phosphorylating multiple protein substrates, we designed additional inhibitors using the same rational approach. Table 1 lists three of these potential inhibitors. One derived from δPKC and another substrate, annexin V (ANXA5).54 Another one derived from a substrate of the cyclic AMP-depend protein kinase (PKA),55 and the last one from a substrate of protein kinase B or Akt (PKB/Akt).56 Identifying the particular substrate that mediates a given function involves extensive mutagenesis, which is time-consuming and expensive. We suggest that our rational approach can provide a quick path to generate highly selective and effective inhibitors of pleiotropic protein kinases, to be used in basic research and as leads for novel drugs.

Table 1.

Rational design of potential inhibitors of three Ser/Thr kinases for one of their substrates.

denotes identity,

denotes homology and

denotes opposite charge.

Sequence alignment of δPKC, cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and protein kinase B (PKB) with one of their substrates identifies short sequences of homology that likely represents docking site for that kinase on the corresponding substrate. For δPKC we identified another substrate, annexin V (ANXA5). For PKA we identified the docking site on cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein 1 (CREB)55. And for PKB we identified docking site on the apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)56. Shown is a heat-map of the conservation of these sequences in evolution and color code for conservation. Peptides corresponding to each of these short sequences should be effective inhibitor of the corresponding kinases and therefore useful pharmacological tools to determine what is the functional consequence of phosphorylation of that substrate by the given kinase.

Conclusion

In this study, we describe a rational approach to develop a selective inhibitory peptide for a kinase phosphorylation of one of its many substrates as a mean to determine the functional contribution of this one substrate. This approach is fast and inexpensive as compared to screening of big chemical libraries to identify an inhibitor, and is not as laborious as mutating each phosphorylation site on a given protein substrate. To date, over 50 peptides have been approved for clinical use, resulting in many therapeutic products, such as cyclosporin A, tyrocidine A, gramicidin S, and somatostatin,57 and in 2013, their market value was estimated to be $15 billion.58 Although not examined in details in this study, peptide modification, such as N-methylation, the use of D-amino acids and cyclization was shown to improve peptides stability and bioavailability. Therefore, the use of rational approach to identify inhibitory peptides is a promising approach to develop novel therapeutics.

In addition to the potential acute use of ψPDK analogs for the treatment of heart attack, PDK activation contributes to cardiac dysfunction and heart failure,59,60 suggesting that PDK inhibition may be an effective target for treating chronic heart disease. However, although small molecule PDK inhibitors can increase the recovery rate of cardiac function following simulated myocardial infarction in vitro,61,62 these PDK inhibitors cause myocardial steatosis and sometimes death within a few days of treatment in vivo.63 In contrast, ψPDK1 peptide selectively inhibited only excessive activation of PDK by δPKC, but not basal PDK activity. Therefore, ψPDK1 peptide will likely have a therapeutic advantage over other inhibitors of PDK activity.64

Finally, because δPKC mediates different and sometimes opposing effects,65 depending on the substrates that it phosphorylates, ψPDK1 peptide has also an advantage relative to other existing δPKC kinase inhibitors (e.g., the ATP competitive inhibitor, rottlerin66 and the anchoring inhibitory peptide, δV1-139,47). Since it does not affect other potentially protective δPKC-mediated functions, ψPDK1 peptide can be used in cases when it is necessary to target only this particular substrate of δPKC, such as following myocardial infarction.

Experimental Methods

Peptide synthesis

In brief: Peptides were synthesized on solid support using a fully automated microwave peptide synthesizer (Liberty, CEM Corporation). The peptides were synthesized by solid phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) methodology67 with a fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)/tert-Butyl (tBu) protocol. The lysine side chain was protected with N-methyltrityl (Mtt), a protection group that can be deprotected selectively using acid labile conditions.68 After completion of the synthesis of the linear peptide, an anhydride spacer was coupled to the N-terminal amino group and cyclization was performed using amide bonds between the moiety linker at the backbone N-terminus and an epsilon amino on the side chain of a C-terminal Lys residue,69,70 The final cleavage and side chain deprotection was done manually without microwave energy. Peptides were analyzed by analytical reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) (Shimadzu, MD, USA) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) mass spectrometry (MS) and purified by preparative RP-HPLC (Shimadzu, MD, USA). For full details, see supporting information.

Sequence alignments

Sequences from different species were aligned using Lalign server, using the following δPKC proteins: Homo sapiens (Q05655), Mus musculus (P28867), Rattus norvegicus (P09215), Gallus gallus (gi|57524924), and Danio rerio (gi|47550719) ; PDK proteins: Homo sapiens (Q15119), Mus musculus (Q9JK42), Rattus norvegicus (Q64536), Gallus gallus (gi|315583003), Danio rerio (gi|41055902), Ascaris suum (worm) (O02623) and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (yeast) (P40530); εPKC protein: human (Q02156) and θPKC protein: human (Q04759).The details about additional proteins used for sequence alignments are in Supplementary Table 1.

ψPDK inhibits PDK/δPKC interaction in vitro

200 ng recombinant δPKC (Invitrogen, CA, USA) was incubated with or without the indicated peptides (1 µM) for 10 min, prior to adding 300 ng recombinant PDK2-GST (Abnova, Taiwan) for 20 min at 37 °C. PDK was immunoprecipitated using anti-PDK (AP9827a, Abgent, CA, USA) and δPKC binding to PDK was determined using rabbit anti-δPKC antibodies (C-17, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). The intensity of the spots was measured using NIH ImageJ.71

ψPDK inhibits PDK phosphorylation by δPKC in vitro

200 ng recombinant δPKC protein (Invitrogen, CA, USA) was incubated with or without the peptides (5 nM - 1 µM) for 10 min, then 200 ng recombinant PDK2 (Abcam, UK) was added for 10 min at 37 °C in kinase buffer (40 µl) Tris-HCl (20 mmol/L), MgCl2 (20 mmol/L), DTT (1 µmol/L), ATP (25 µmol/L) and CaCl2 (1 mmol/L) in the presence of the PKC activators, phosphatidylserine (PS, 1.25 µg) and 1,2 dioleoyl sn-glycerol (DG, 0.04 µg). The kinase assay was terminated by adding loading Laemmli buffer containing 5% SDS and the samples were loaded on a 10% PAGE-SDS polyacrylamide gel, and the levels of phosphorylated PDK2 protein were determined using anti-phospho-threonine (9381S and 2351S, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) and anti-phosphoser PKC substrate (2261L, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) antibodies. The nitrocellulose was also reprobed using anti-PDK (AP9827a, Abgent, CA, USA) to confirm that equal amounts of PDK were used. The intensity of the spots was measured using NIH ImageJ.71

ψPDK binding to δPKC and εPKC in vitro

Binding data of δPKC and εPKC to immobilized ψPDK or control peptide (ALSAER) in vitro was gathered using an AGILE Dev Kit label-free binding assay (Nanomedical Diagnostics Inc, CA, USA), following their standard protocol. 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDAC) (2 mg) and sulfo-N-Hydroxysuccinimide (sNHS) (6 mg) from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA) were used in MES buffer (pH 6.0, 5 ml) for 15 min to covalently attach the amine of the peptide the carboxyl on the chip. Peptide solution (6 µM) was incubated with the chip for 15 min. Next, an amine terminated short chain polyethylene glycol (3 mM) followed by ethylamine (1 M) were applied serially for 15 min each to quench remaining unoccupied binding sites on the chip. After a rinse in PBS, baseline current levels for the chip were recorded for at least 2 min. Next, the PBS was aspirated and a 30 µl droplet of the tested protein (75 µg/mL, recombinant δPKC, Invitrogen, CA, USA) was applied to the chip and the change in the sensor chip readout was recorded for 15 min. Additional measurements were performed using varying concentrations or using recombinant εPKC (75 µg/mL, GenWay, CA, USA), as a control. After data were gathered, the responses of 25 sensors on a single assay chip were averaged, and any background drift recorded in PBS was subtracted. A Hill equation fit was used to determine a Kd. Kd values were also calculated by measurement of the Kon and Koff values at a single concentration. This was done by fitting the binding curve to a double exponential function and the first rinse to a single exponential using a single concentration for the tested peptides and values obtained by these calculation methods were almost identical.

Animal studies

Based on our previous experience, a minimum of six rodents per group is required to obtain statistically meaningful data.40 An experimental group size of six or more animals is necessary to achieve at least a 20% minimal difference for a power of 95% with a < 0.05 and b < 20%. All treatments were performed between 9:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. by observers blinded to the treatment groups. Rodent were housed in a temperature-and light-controlled room for at least 3 days before use. All animals were randomized and assigned to testing groups to generate biological replicates for each group.

Animal care

Animal care and husbandry procedures were in accordance with established institutional and National Institutes of Health guidelines. The animal protocols were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and by the Jinan University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Ex vivo rat heart model of myocardial infarction-induced ischemia and reperfusion injury

An ex vivo model of acute ischemic heart injury was carried out as previously described.39 Briefly, Wistar male rats (250–275 g) four to six weeks old, purchased from Charles River (MA, USA) were heparinized (1000 units/kg; intraperitoneal injection), anesthetized with Beuthanasia-D (100 mg/kg intraperitoneal injection), and then were treated with different peptides. Hearts were rapidly excised and then perfused with an oxygenated Krebs-Henseleit buffer containing NaCl (120 mmol/liter), KCl (5.8 mmol/liter), NaHCO3 (25 mmol/liter), NaH2PO4 (1.2 mmol/liter), MgSO4 (1.2 mmol/liter), CaCl2 (1.0 mmol/liter) and dextrose (10 mmol/liter) at pH 7.4 and 37 °C in a Langendorff coronary perfusion system. A constant coronary flow rate of 10 ml/min was used. Hearts were submerged into a heat-jacketed organ bath at 37 °C. After 10 min of equilibration, the hearts were subjected to 30 min of global ischemia and 60 min of reperfusion. The hearts were perfused with 500 pM - 1 µM peptides for 20 min immediately following the ischemic period. Normoxic control hearts were subjected to 90 min of perfusion in the absence of ischemia. Coronary effluent was collected to determine creatine kinase (CK) release during the first 30 min of the reperfusion period. At the end of the reperfusion period, hearts were sliced into 1-mm-thick transverse sections and incubated in triphenyltetrazolium chloride solution (TTC, 1% in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 15 min. Infarct size, expressed as a percentage of the risk zone (equivalent to total muscle mass), CK release and JNK phosphorylation were used to assess cardiac damage, as described previously.39,72 Hearts were excluded from the study if they met one of the following criteria: (1) time to perfusion over 3 min, (2) coronary flow was outside the range of 9–15 ml/min or (3) heart rate was below 240 beats/min or appearance of severe arrhythmia.

In vivo rat acute ischemia and reperfusion (acute myocardial infarction) model

An open chest model was carried out using Sprague Dawley male rats (200–230 g) from Jinan University. After inducing anesthesia with isoflurane (2.5% in air), artificial respiration was set via cannulation (rate: 120 breaths/min; volume 2 ml/time; body temperature was maintained at 37 °C). Left thoracotomy was performed between the fourth and fifth ribs to expose the heart. After opening the pericardial cavity and 10 min equilibrium, the left anterior descending coronary artery (LAD) was ligated with 3-0 silk suture at the middle part of the left coronary artery. Occlusion was determined by observation of immediate pallor of the left ventricular free wall. 30 min after artery ligation, the suture was released and flow was recovered in the coronary artery. Where indicated, peptides (2 mg/kg) were injected intraperitoneally at reperfusion. The normoxia control animals (sham) were exposed to the same procedure with no ligation. The chest was then closed in layers with 2-0 silk suture and twenty four hours later, the animals were euthanatized with an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) delivered by intraperitoneal injection. The chest was opened and the heart was isolated for further infarct size analysis.

In vivo peptide toxicity assay

BALB/c mice (23 to 26 g, six to eight weeks old), were treated with the peptides (six-eight mice per group) for six weeks to assess their toxicity. Osmotic pumps (#2002, 0.5 µl/h, Alzet, CA, USA) filled with ψPDK1 (2 mg/kg/day) or control peptide were implanted subcutaneously on the back of the mice following anesthesia using a standard surgical procedure as recommended by the manufacturer.

Western blot analysis and 2D-gel analysis

Rat hearts were homogenized in a buffer A (mannitol (210 mmol/L), sucrose (70 mmol/L), MOPS (5 mmol/L) and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (1 mmol/L)) in the presence of protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) followed by isolation of the mitochondrial fraction. Tissue extract was centrifuged at 700 g to pellet nuclei and unbroken cellular debris, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 g to collect mitochondrial-enriched fractions, as described.73

For protein phosphorylation, fractions were resuspended in buffer A. For 2-D IEF/SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, the samples were homogenized in buffer consisting of urea (7 mol/L), thiourea (2 mol/L) and CHAPS (4%) in the presence of protease inhibitor and phosphatase inhibitor mixtures (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Supernatants were subjected to a first dimensional separation by an IPGphor isoelectric focus power supply using pre-cast Immobilin DryStrip pI 3–10 strips according to the manufacturer’s instruction manual (Amersham Biosciences, NJ, USA). 10% SDS gel electrophoresis and Western blotting were carried out using anti-PDK2 (AP9827a, Abgent, CA, USA), anti-PDH (456600, Invitrogen, CA, USA), anti-ALDH2 (48837, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), anti-phospho-threonine (9381S and 2351S, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) and anti-phospho-serine PKC substrate (2261L, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) antibodies. Phosphatase treatment confirmed that the leftward shift in PDK mobility is due to phosphorylation.31 The intensity of the spots was measured using NIH ImageJ.71

Phosphorylation of HSP27, MARCKS, STAT, Troponin I and JNK in the ex vivo model were determined on 1D SDS PAGE, using anti-phospho HSP27 (04–447, EMD Millipore, MA, USA) and anti-HSP27 (ADI-SPA-800-F, Enzo Life Sciences, NY, USA), anti-phospho-MARCKS (2741, Cell signaling, MA, USA) and anti-MARCKS (6455, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-phospho STAT (8826S, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) and anti-STAT (346, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-phospho Troponin I (4004, Cell signaling, MA, USA) and anti-Troponin I (31655, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-phospho-SAPK/JNK (9251, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) and anti-SAPK/JNK (9252, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) antibodies. The levels of phosphorylated substrates were normalized for total substrate and presented as a ratio to the material from hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion in the presence of treatment. The intensity of the spots were measured using NIH ImageJ.71

Phosphorylation of GAPDH in the ex vivo model was determined after immunoprecipitation. Samples were incubated with anti-GAPDH antibody (Mab6C5, Advanced immunochemical, CA, USA) in buffer containing Tris-base, pH 7.4 (10 mM), NaCl (150 mM), Triton X-100 (0.1%), EDTA, pH 8 (5 mM) and protease inhibitor overnight at 4 °C with gentle agitation. Protein A/G beads were then added, and the mixture was incubated for 2 hours at 4 °C. The mixture was centrifuged for 1 min at 800 g and the immunoprecipitates were washed three times with buffer and analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and followed by Western blot using anti-phospho-threonine (9381S and 2351S, Cell Signaling, MA, USA), anti-phospho-serine PKC substrate (2261L, Cell Signaling, MA, USA) and anti-GAPDH (Mab6C5, Advanced immunochemical, CA, USA) antibodies. The levels of phosphorylated substrates were normalized for total substrate and presented as a ratio to the material from hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion in the presence of control peptide. The intensity of the spots was measured using NIH ImageJ.71

ATP level determination

Following the ex vivo ischemia/reperfusion experiment, 100 mg heart tissue was homogenized in 1% TCA (500 µl). The lysate was spun to remove debris and the pH was adjusted to pH 7.4. 10 µl of the lysate were used in a 200 µl assay for quantitative determination of ATP levels with recombinant firefly luciferase and its substrate, D-luciferin, according to the manufacture’s protocol (Invitrogen, NY, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are provided as means ± SEM, the number of independent experiments performed is provided in each data set. Data were tested for significance by using the two tailed unpaired Student t-test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P values were <0.05. Sample sizes were estimated based on previous experience of similar assays and the effect size observed in preliminary experiments. All samples were identical prior to allocation of treatments and the observer was blinded to the experimental conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HL52141 to D.M.-R.

We thank Dr. Churchill for preliminary results using the Langendorff apparatus, Dr. Hansen, and the late Dr. Adrienne Gordon for critical advice. Nanomedical Diagnostics provided assistance in use of the AGILE Dev Kit binding assay and analysis of the results. In memory of Dr. Miry C. Souroujon.

ABBREVIATIONS

- δPKC

delta protein kinase C

- PDK

pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Experimental details, additional figures and data are available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

REFERNCES

- 1.Parang K, Sun G. Drug Discovery Handbook. 2005:1191–1257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ubersax JA, Ferrell JE., Jr Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:530–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemeer S, Heck AJ. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:414–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanks SK, Quinn AM, Hunter T. Science. 1988;241:42–52. doi: 10.1126/science.3291115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muller S, Chaikuad A, Gray NS, Knapp S. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2015;11:818–821. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remenyi A, Good MC, Lim WA. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2006;16:676–685. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhattacharyya RP, Remenyi A, Yeh BJ, Lim WA. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2006;75:655–680. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams PD, Li X, Sellers WR, Baker KB, Leng X, Harper JW, Taya Y, Kaelin WG., Jr Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:1068–1080. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.2.1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams PD, Sellers WR, Sharma SK, Wu AD, Nalin CM, Kaelin WG., Jr Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:6623–6633. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.6623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang CI, Xu BE, Akella R, Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:1241–1249. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kallunki T, Deng T, Hibi M, Karin M. Cell. 1996;87:929–939. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81999-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee T, Hoofnagle AN, Kabuyama Y, Stroud J, Min X, Goldsmith EJ, Chen L, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:43–55. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00161-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luciani MG, Hutchins JR, Zheleva D, Hupp TR. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;300:503–518. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulman BA, Lindstrom DL, Harlow E. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:10453–10458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanoue T, Maeda R, Adachi M, Nishida E. EMBO J. 2001;20:466–479. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.3.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee S, Lin X, Nam NH, Parang K, Sun G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 2003;100:14707–14712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2534493100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bononi A, Agnoletto C, De Marchi E, Marchi S, Patergnani S, Bonora M, Giorgi C, Missiroli S, Poletti F, Rimessi A, Pinton P. Enzyme research. 2011;2011:1–26. doi: 10.4061/2011/329098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steinberg SF. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:1341–1378. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00034.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roffey J, Rosse C, Linch M, Hibbert A, McDonald NQ, Parker PJ. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009;21:268–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Churchill EN, Qvit N, Mochly-Rosen D. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2009;20:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Souroujon MC, Mochly-Rosen D. Nat. Biotechnol. 1998;16:919–924. doi: 10.1038/nbt1098-919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qvit N, Mochly-Rosen D. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2010;7:e87–e93. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sobhia ME, Grewal BK, Ml SP, Patel J, Kaur A, Haokip T, Kokkula A. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2013;23:1297–1315. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.805205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu-Zhang AX, Newton AC. Biochem. J. 2013;452:195–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20130220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ono Y, Fujii T, Ogita K, Kikkawa U, Igarashi K, Nishizuka Y. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:6927–6932. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim EH, Lee HJ, Lee DH, Bae S, Soh JW, Jeoung D, Kim J, Cho CK, Lee YJ, Lee YS. Cancer. Res. 2007;67:6333–6341. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, O'Connor KL, Greeley GH, Jr, Blackshear PJ, Townsend CM, Jr, Evers BM. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:8351–8357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409431200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novotny-Diermayr V, Zhang T, Gu L, Cao X. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:49134–49142. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206727200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yogalingam G, Hwang S, Ferreira JC, Mochly-Rosen D. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:18947–18960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noland TA, Jr, Raynor RL, Kuo JF. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:20778–20785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Churchill EN, Murriel CL, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D, Szweda LI. Circ. Res. 2005;97:78–85. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000173896.32522.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim J, Koyanagi T, Mochly-Rosen D. The Prostate. 2011;71:946–954. doi: 10.1002/pros.21310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bright R, Raval AP, Dembner JM, Perez-Pinzon MA, Steinberg GK, Yenari MA, Mochly-Rosen D. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6880–6888. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4474-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kilpatrick LE, Standage SW, Li H, Raj NR, Korchak HM, Wolfson MR, Deutschman CS. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2011;89:3–10. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0510281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pereira S, Park E, Mori Y, Haber CA, Han P, Uchida T, Stavar L, Oprescu AI, Koulajian K, Ivovic A, Yu Z, Li D, Bowman TA, Dewald J, El-Benna J, Brindley DN, Gutierrez-Juarez R, Lam TK, Najjar SM, McKay RA, Bhanot S, Fantus IG, Giacca A. Am.. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;307:E34–E46. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00436.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geraldes P, Hiraoka-Yamamoto J, Matsumoto M, Clermont A, Leitges M, Marette A, Aiello LP, Kern TS, King GL. Nat. Med. 2009;15:1298–1306. doi: 10.1038/nm.2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qi X, Inagaki K, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:173–182. doi: 10.1172/JCI32636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qi X, Disatnik MH, Shen N, Sobel RA, Mochly-Rosen D. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:256–265. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-06-0551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen L, Hahn H, Wu G, Chen CH, Liron T, Schechtman D, Cavallaro G, Banci L, Guo Y, Bolli R, Dorn GW, 2nd, Mochly-Rosen D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U. S. A. 2001;98:11114–11119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191369098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inagaki K, Chen L, Ikeno F, Lee FH, Imahashi K, Bouley DM, Rezaee M, Yock PG, Murphy E, Mochly-Rosen D. Circulation. 2003;108:2304–2307. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101682.24138.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kemp BE, Parker MW, Hu S, Tiganis T, House C. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1994;19:440–444. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gump JM, Dowdy SF. Trends. Mol. Med. 2007;13:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwarze SR, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy SF. Science. 1999;285:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5433.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Begley R, Liron T, Baryza J, Mochly-Rosen D. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;318:949–954. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bates E, Bode C, Costa M, Gibson CM, Granger C, Green C, Grimes K, Harrington R, Huber K, Kleiman N, Mochly-Rosen D, Roe M, Sadowski Z, Solomon S, Widimsky P. Circulation. 2008;117:886–896. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.759167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnson RM, Harrison SD, Maclean D. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2011;683:535–551. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-919-2_38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mochly-Rosen D, Das K, Grimes KV. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2012;11:937–957. doi: 10.1038/nrd3871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rizzuti M, Nizzardo M, Zanetta C, Ramirez A, Corti S. Drug discovery today. 2015;20:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lonn P, Dowdy SF. Expert opinion on drug delivery. 2015;12:1627–1636. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2015.1046431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang S, Hulver MW, McMillan RP, Cline MA, Gilbert ER. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2014;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen CH, Budas GR, Churchill EN, Disatnik MH, Hurley TD, Mochly-Rosen D. Science. 2008;321:1493–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1158554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inagaki K, Koyanagi T, Berry NC, Sun L, Mochly-Rosen D. Hypertension. 2008;51:1565–1569. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steinberg SF. Biochem. J. 2004;384:449–459. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kheifets V, Bright R, Inagaki K, Schechtman D, Mochly-Rosen D. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:23218–23226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602075200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez GA, Montminy MR. Cell. 1989;59:675–680. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim AH, Khursigara G, Sun X, Franke TF, Chao MV. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:893–901. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.3.893-901.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joo SH. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2012;20:19–26. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2012.20.1.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vlieghe P, Lisowski V, Martinez J, Khrestchatisky M. Drug discovery today. 2010;15:40–56. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mori J, Alrob OA, Wagg CS, Harris RA, Lopaschuk GD, Oudit GY. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2013;304:H1103–H1113. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00636.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Atherton HJ, Dodd MS, Heather LC, Schroeder MA, Griffin JL, Radda GK, Clarke K, Tyler DJ. Circulation. 2011;123:2552–2561. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.011387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Itoi T, Huang L, Lopaschuk GD. Am. J. Physiol. 1993;265:H427–H433. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.2.H427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McVeigh JJ, Lopaschuk GD. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259:H1079–H1085. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.4.H1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones HB, Reens J, Johnson E, Brocklehurst S, Slater I. Toxicol. Pathol. 2014;42:1250–1266. doi: 10.1177/0192623314530195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang SL, Hu X, Zhang W, Yao H, Tam KY. Drug discovery today. 2015;20:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basu A, Pal D. Scientific World Journal. 2010;10:2272–2284. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soltoff SP. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007;28:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Merrifield RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963;85:2149–2154. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Aletras A, Barlos K, Gatos D, Koutsogianni S, Mamos P. Int. J. Pept. Protein. Res. 1995;45:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1995.tb01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gilon C, Halle D, Chorev M, Selinger Z, Byk G. Biopolymers. 1991;31:745–750. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qvit N. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2014;85:300–305. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abràmoff MD, Magalhães PJ, Ram SJ. Biophotonics international. 2004;11:36–43. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Budas GR, Disatnik MH, Chen CH, Mochly-Rosen D. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;48:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Churchill EN, Disatnik MH, Budas GR, Mochly-Rosen D. Ther. Adv. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2008;2:469–483. doi: 10.1177/1753944708094735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.