Abstract

Background

Many individuals engage in regulation attempts to manage or reduce their partner’s alcohol use. Research on partner social control behaviors has shown that regulation attempts generally factor into negative (i.e., punishing) and positive (i.e., rewarding) dimensions. In the alcohol domain, partner drinking has been associated with poorer relationship functioning through punishment.

Objectives

This research applied a dyadic growth model approach to investigate changes in alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences over six months, and evaluated whether partner regulation attempts (punishment and reward) were influential (i.e., successful) in these changes.

Methods

Married couples (N = 123 dyads) completed web-based measures of partner regulation attempts, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related consequences three times over a six-month period.

Results

Results from dyadic growth curve analyses showed that partner punishment was significantly associated with increases in alcohol-related consequences—and marginally associated with increases in alcohol consumption—over the six-month period. Partner reward was associated with decreases in consumption over the study period. These effects were not different for husbands and wives.

Conclusion/Importance

Results support previous research demonstrating deleterious impact of partner punishing control strategies and provide important implications for future interventions and treatment.

Keywords: Punishment, reward, social control, problem drinking, marriage, alcohol

When a person’s alcohol use is perceived to be a problem, partners may expend a great deal of effort in an attempt to limit or regulate the drinker’s consumption. One critical question to be addressed by the literature is whether regulation strategies used by partners are successful at reducing drinking. The current research utilizes a dyadic growth curve approach to evaluate whether partner regulation attempts influence alcohol consumption and related consequences over time among married couples.

Alcohol and the Marital Relationship

Alcohol use is often recognized as a source of strain in romantic relationships (Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Marshal, 2003). Substance use is the third most cited reason for divorce (Amato & Previti, 2003) and rates of separation and divorce are considerably higher among couples with an alcohol abusive or dependent partner (Marshal, 2003; McCrady, 2012). Research has shown that spouses of heavy drinking partners report higher rates of depression, anxiety, relationship distress, and more frequent reports of physical and emotional abuse (Fischer et al., 2005; Halford, Bouma, Kelly, & Young, 1999; Homish, Leonard, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2006; Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Leonard & Jacob, 1988; Leonard & Senchak, 1993, 1996; Maisto, McKay, & O’Farrell, 1998; Murphy & O’Farrell, 1994). Considering how distressing having a heavy drinking partner may be (McCrady, Epstein, & Kahler, 1998), efforts to help spouses cope with and manage their partner’s drinking are valuable to future treatment and preventative strategies.

Partner Regulation Attempts

At some point, all individuals engage in some form or extent of unhealthy behavior. Research has examined partner influence in a wide range of behaviors, ranging from unhealthy eating to imperfect dental hygiene to foregoing regular physician check-ups. Importantly, relationship partners are among the first to notice and attempt to change an individual’s unhealthy behavior (Lewis & Rook, 1999; Room, Greenfield, & Weisner, 1991).

Regulation strategies are employed with intentions to benefit the person engaging in the behavior. The strategies may be utilized under the assumption that pushing a person to understand how destructive a particular behavior is will result in a decreased engagement in the behavior. However, to the extent that the strategies cause additional strain, they may serve to exacerbate the unhealthy behavior and the relationship by not providing the right kind of motivation to change or by adding interpersonal stress. Lund and colleagues (2014) examined the relationship between stressful social relationships and all-cause mortality and found that endorsement of ‘frequent worries or demands’ from a significant other was associated with a 50–100% increased risk of mortality, after controlling for several relevant factors (e.g., gender, age, socioeconomic and cohabitation status, prior hospitalization). Moreover, because attempts to change a partner’s behavior can be perceived as dissatisfaction with the relationship, they can result in poorer relationship outcomes (Overall et al., 2006; Overall & Fletcher, 2010).

Regulation strategies have often been distinguished along a positive (e.g., positive reinforcement, encouragement, modeling) and negative (e.g., pressuring, punishing) dimensionality, with positive attempts being more strongly associated with beneficial change and functioning and negative attempts more strongly associated with deleterious outcomes (Craddock, vanDellen, Novak, & Ranby, 2015; Fekete, Stephens, Druley, & Greene, 2006; Lewis & Rook, 1999; Okun, Huff, August, & Rook, 2007; Tucker & Anders, 2001). In the domain of alcohol use, increased partner drinking and perceiving one’s partner to have a drinking problem are associated with poorer relationship functioning (e.g., satisfaction, trust), and these associations are mediated by punishing strategies, not rewarding ones (Rodriguez, DiBello, & Neighbors, 2013; Rodriguez, DiBello, & Wickham, 2016). Further, Philpott and Christie (2008) found that when husbands of alcoholic wives emphasized the positive consequences of sobriety, the wives experienced less emotional, psychological, and marital distress. However, when husbands used confrontational coping techniques, wives reported greater distress. Independent of how spousal use of these strategies affect the spouses themselves and the drinkers’ psychological well-being, spouses play a critical role in attempts to manage their partner’s drinking (Raitasalo & Holmila, 2005). Spouses may try to reduce the drinking in a variety of ways, including subtle requests, suggesting alternative nondrinking activities, pleading to change, pouring out drinks, criticizing, threatening to leave or place the drinker in treatment, and turning to clinicians for help (for a review, see Rotunda & Doman, 2001; Thomas & Ager, 1993). The frequency of these strategies increases as the severity of the alcohol problem increases. When milder levels of attempts (e.g., a simple request to reduce number of drinks) are unsuccessful, partners may use more serious forms (e.g., threats to leave) in an attempt to regulate the drinker’s behavior (Raine, 2000).

In addition, most spouses report that their partner’s drinking is unaffected by their attempts (Thomas & Ager, 1993). Some work has shown that behaviors such as reinforcing positive consequences of sobriety are more adaptive responses to partner drinking (Halford, Price, Kelly, Bouma, & Young, 2001). Other work has shown that reinforcing positive strategies are associated with less psychological and relational distress in partners, whereas confrontational strategies are associated with greater distress (Kahler, McCrady, & Epstein, 2003). It is unclear, however, whether these attempts are successful at changing a partner’s drinking.

Current Research

Growth modeling is designed to describe changes in an outcome over time, and to predict these changes using person- and dyad-level variables. In the current research, we applied a dyadic growth approach to examine changes in alcohol consumption and related consequences over time (controlling for consumption), as well as to determine whether those changes could be predicted by partner regulation attempts. In other words, we were interested in whether partner regulation strategies were successful at modifying their partner’s behavior. Specifically, how is punishment for drinking (or reward for not drinking) associated with actual changes in the partner’s alcohol consumption and related consequences over time? Based on previous findings related to social control, we expected punishment to be associated with either no change or increases in partner drinking and related consequences. We also expected reward to be associated with either no change or decreases in partner drinking and related consequences. Further, while some work has shown that men are targets of partner social control behaviors more than women (e.g., Asher, 1992; Hemstrom, 2002; Holmila, 1988; Holmila, Mustonen, & Rannik, 1990; Umbertson, 1992; Wiseman, 1991), we aimed to examine whether partner effects on changes in alcohol consumption and related consequences were different for husbands and wives.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Sample characteristics

Inclusion criteria for longitudinal participation included that couples were heterosexual, married, and between 18–50 years old. As part of the recruitment strategy, inclusion criteria also involved that at least one spouse must have reported consuming alcohol one or more times per week, and at least one spouse was enrolled as an undergraduate student. Participants were, on average, 29.76 years old (SD = 6.14 years). The majority (69.6%) classified themselves as Caucasian, with 9.2% African American, 7.7% Asian, 7.3% Other, 5.0% Multi-ethnic, .8% Native American/American Indian, and .4% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. About a quarter of the sample (26.5%) identified as Hispanic/Latino. Couples had been married, on average, for 4.26 years (SD = 5.08 years). More than half (58.9%) worked full-time, with 20.4% working part-time and 20.8% did not work. Approximately half (52.0%) of the sample were students (34.8% full-time students and 17.2% half-time status).

Procedure

Participants determined whether they met the inclusion criteria and contacted the researcher via email to indicate their interest in participating in the study. Spouses were asked to complete the web-based survey at a time and location where they were alone. Follow-ups, identical to baseline, were collected three and six months later. Couples were compensated $15 in Target giftcards (and extra credit if desired) for each assessment. All study procedures were approved by the University Institutional Review Board.

Recruitment and attrition

Recruitment was conducted on the campus of a large urban university in the southern U.S. Individuals were invited to participate via flyers, classroom recruitment, and department listserv emails. Spouses were invited via email. The baseline assessment was completed by 133 dyads (N = 266). Three check questions were placed at various places in each survey to assess whether participants were paying attention (e.g., “Please select ‘do not agree at all’ as the response to this question”; couples in which one or both partners answered two or more check questions incorrectly were removed from the analyses. A total of 10 couples were dropped; thus, the final dataset was comprised of 123 couples (N = 246). Of the individuals who completed baseline, 200 (90 complete couples) completed the three-month follow-up and 159 (65 complete couples) completed the six-month follow-up. This project was a graduate student training grant and did not provide funding for participant payment; although another small grant was obtained to provide limited participant payment, it is likely the relatively low follow-up rate is at least partially due to the amount of compensation. Those who dropped participation were more likely to be male (41.4% women and 58.6% men were non-completers, p<.05). Individuals who did not complete the follow-ups did not differ from completers in their age, alcohol use/consequences, or use of partner regulation strategies (all ps>.20).

Measures

Partner regulation attempts

The Partner Management Scale (PMS; Rodriguez et al., 2013) was used to assess regulation attempts. The measure asks participants how often they have engaged in 19 behaviors to change their partner’s drinking, from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Very often). This scale classifies regulation behaviors into punishment (example items “Punishing him/her for drinking,” “Yelling about his/her drinking,” “Expressing anger at his/her drinking”; αwife = .91, αhusband = .91) and reward (example items “Suggesting alternative activities without alcohol,” “Letting him/her know how much I appreciate the time we spend when he/she is not drinking”; αwife = .88, αhusband = .89) subscales.

Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985) was included as a covariate in the dyadic growth models. The DDQ asks participants the average number of drinks consumed for each day of the week over the previous three months. Responses are summed to create a score of the average number of drinks per week consumed.

Negative alcohol-related consequences

Negative alcohol-related consequences were assessed with the Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989). The RAPI assesses how often participants have experienced 23 alcohol-related consequences over the past three months. Example items include, “Had withdrawal symptoms,” “Caused shame or embarrassment to someone,” “Neglected your responsibilities,” and “Felt that you had a problem with alcohol.” The RAPI was modified to include two additional items (i.e., “drove after having two drinks” and “drove after having four drinks”). Responses were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale (0 = never; 1 = 1 to 2 times; 2 = 3 to 5 times; 3 = 6 to 10 times; 4 = more than 10 times). RAPI scores were calculated by summing the items (αwife = .86, αhusband = .95).

Analysis Plan

The analysis plan was designed to take advantage of the dyadic structure of the data by using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). One advantage of the APIM is that the models capitalize on nonindependence by examining how one’s own outcome can be predicted by one’s own variables (i.e., actor effects) as well as by one’s partner’s variables (i.e., partner effects). Obtaining longitudinal dyadic data allows for examination of changes in key variables over time. Conceptually, dyadic growth modeling first examines changes in the outcome (in this case, alcohol consumption and related consequences) over time for each person. The current research tested two models: one examining changes in alcohol consumption and another examining changes in negative alcohol-related consequences after controlling for alcohol consumption. The model predicting consumption specified that a person’s alcohol consumption is a function of an intercept (the predicted consumption at baseline) and a slope (the change in consumption every three months). The model predicting alcohol-related consequences was identical, with the exception that consumption was included as a covariate. In dyadic growth models, both members of a dyad have their own intercepts and slopes and these values may be correlated across dyad members. Time was coded in the current research to begin with the baseline assessment, with each unit corresponding to a three-month lag in time. All predictor variables were grand mean centered. The intercept of these growth models reflects drinking (i.e., consumption or consequences) at baseline (Time 0), and the slope coefficient reflects the average change in drinking (i.e., consumption or consequences) for each three-month increase in time.

After testing for whether husbands and wives should be analyzed as distinguishable, a mixed-effects modeling framework in SAS 9.4 Proc Mixed was used to assess the extent to which a person’s drinking (consumption or consequences) at Time 0 (i.e., intercept) and his/her change in drinking (consumption or consequences) over time (i.e., slope) were predicted by both his/her own baseline punishment and reward (i.e., actor effects) and his/her spouse’s baseline punishment and reward (i.e., partner effects). The model further specified four random effects (i.e., two random intercepts and two random slopes) and that intercepts and slopes were allowed to covary within and between dyads. The residual error structure was specified as heterogeneous compound symmetry, meaning that the variances of the residuals at each time point for individuals and the covariances between spouses’ residuals at the three time points were free to vary. Finally, analyses evaluated interactions with gender to examine whether the partner effects of punishment and reward on changes in drinking and consequences were different for husbands and wives.

Results

Distinguishability

For both alcohol-related outcomes, we tested distinguishability with structural equation modeling by comparing a model where paths on intercepts and slopes were free to vary for husbands and wives with a model where they were constrained to be equal. Constraining actor and partner paths of punishment and reward to be equal for husbands and wives resulted in a significant decrease in model fit for consumption, χ2(8) = 17.52, p=.025, and for consequences, χ2(8) = 24.30, p=.019. Thus, husbands and wives were considered distinguishable.

Descriptive Statistics

Means, standard deviations, and stability paths are provided for all timepoints separately for husbands and wives in Table 1. Tests of gender differences showed that men reported higher levels of alcohol consumption and women reported higher levels of punishment and reward (all ps<.01). Men and women did not report different levels of alcohol-related consequences (p=.212).

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Variables at Each Assessment and Stability Paths for Men and Women

| Variable | Assessment | Stability Paths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline M(SD) | 3-month M(SD) | 6-month M(SD) | BL→3M | 3M→6M | |

| Men | |||||

| Drinks per week (DDQ) | 8.11 (8.86) | 7.44 (10.12) | 7.00 (7.90) | .75 | .88 |

| RAPI | 3.87 (8.59) | 3.02 (7.33) | 2.41 (6.97) | .82 | .92 |

| Punishment | 1.05 (.21) | 1.13 (.45) | 1.05 (.34) | .71 | .75 |

| Reward | 1.44 (.91) | 1.39 (.80) | 1.30 (.89) | .76 | .85 |

| Women | |||||

| Drinks per week (DDQ) | 4.97 (5.74) | 3.99 (4.30) | 3.79 (4.06) | .58 | .66 |

| RAPI | 2.74 (4.85) | 2.34 (5.14) | 1.77 (5.48) | .59 | .68 |

| Punishment | 1.20 (.79) | 1.23 (.65) | 1.18 (.62) | .76 | .75 |

| Reward | 1.76 (1.26) | 1.72 (1.22) | 1.48 (1.06) | .82 | .80 |

Note. RAPI = Negative alcohol-related consequences. All stability path associations were significant at p < .001.

Correlations among all study variables for husbands and wives at baseline are provided in Table 2. Results showed significant associations between husband and wife drinking and related consequences, but not between husband and wife punishment or reward strategies. Husband drinking and consequences were associated with wife punishment and reward, and wife consequences were associated with husband punishment and reward. Wife consumption was associated with husband reward, but not with husband punishment.

Table 2.

Correlations among All Study Variables at Baseline

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. H DDQ | ||||||||

| 2. W DDQ | .29** | |||||||

| 3. H RAPI | .68*** | .31*** | ||||||

| 4. W RAPI | .18* | .52*** | .23* | |||||

| 5. H Punishment | −.01 | .14 | .12 | .42*** | ||||

| 6. W Punishment | .46*** | .02 | .60*** | .18* | .13 | |||

| 7. H Reward | .04 | .32*** | .15 | .44*** | .65*** | .07 | ||

| 8. W Reward | .35*** | −.01 | .46*** | .20* | .09 | .76*** | .05 |

Note. DDQ = Drinks per week. RAPI = Negative alcohol-related consequences.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Dyadic Growth Models: Changes in Drinking over Time

Alcohol consumption

We first examined whether consumption systematically changed over time for husbands and wives. Results from a model examining time and gender showed that consumption scores decreased over the course of the six months (i.e., the slope), b=−.462, p=.038. A gender moderation test (i.e., time × gender interaction) revealed that overall changes in consumption scores were not different for men and women, b=.181, p=.376.

Negative alcohol-related consequences

We also examined whether alcohol-related consequences changed over time for husbands and wives. Results showed that overall, RAPI scores did not significantly change over time (i.e., the slope), b=−.415, p=.224. Moreover, overall changes in RAPI scores were not different for men and women, b=.096, p=.655.

Changes in Drinking as a Function of Actor and Partner Regulation

We then moved to the primary models of interest to examine how actor and partner regulation were associated with changes in consumption and related consequences. Dyadic growth models were specified where time, gender, time × gender interaction, baseline actor and partner regulation (i.e., punishment and reward), and interactions between actor and partner regulation with time were included to predict alcohol consumption and related consequences. In the model predicting consequences, actor and partner consumption were included as covariates. Results with tests of significance are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Dyadic Growth Models: Fixed Effects of Actor and Partner Regulation on Alcohol Consumption and Related Consequences

| Outcome | Predictor | b | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol Consumption (DDQ) | Intercept | 6.514 | 12.94 | <.001 | 5.518 | 7.511 |

| Effects on DDQ at Time 0 (Intercept) | ||||||

| Time | −.356 | −1.60 | .114 | −.800 | .088 | |

| Gender | .970 | 2.58 | .011 | .225 | 1.715 | |

| Actor Punishment | −.462 | −.50 | .618 | −2.283 | 1.360 | |

| Partner Punishment | 2.065 | 2.05 | .042 | .078 | 4.052 | |

| Actor Reward | −.130 | −.25 | .804 | −1.157 | .898 | |

| Partner Reward | 1.279 | 2.44 | .016 | .246 | 2.312 | |

| Effects on Changes in DDQ (Slope) | ||||||

| Time x Gender | .264 | 1.21 | .229 | −.171 | .699 | |

| Time x Actor Punishment | .115 | .24 | .812 | −.832 | 1.061 | |

| Time x Partner Punishment | 1.013 | 1.93 | .055 | −.020 | 2.046 | |

| Time x Actor Reward | .016 | .06 | .952 | −.500 | .531 | |

| Time x Partner Reward | −.740 | −2.85 | .005 | −1.251 | −.228 | |

|

| ||||||

| Negative Alcohol- Related Consequences (RAPI) | Intercept | 3.279 | 8.44 | <.001 | 2.509 | 4.048 |

| Effects on RAPI at Time 0 (Intercept) | ||||||

| Time | −.130 | −.39 | .700 | −.794 | .535 | |

| Gender | −.397 | −.97 | .332 | −1.206 | .411 | |

| Actor DDQ | .427 | 8.77 | <.001 | .331 | .522 | |

| Partner DDQ | .023 | .48 | .633 | −.071 | .117 | |

| Actor Punishment | −1.146 | −1.39 | .167 | −2.774 | .482 | |

| Partner Punishment | 2.409 | 2.68 | .008 | .641 | 4.177 | |

| Actor Reward | 1.609 | 3.52 | <.001 | .709 | 2.509 | |

| Partner Reward | .667 | 1.44 | .151 | −.246 | 1.580 | |

| Effects on Changes in RAPI (Slope) | ||||||

| Time x Gender | .166 | .69 | .495 | −.314 | .645 | |

| Time x Actor DDQ | −.073 | −1.79 | .075 | −.153 | .008 | |

| Time x Partner DDQ | −.035 | −.80 | .423 | −.121 | .051 | |

| Time x Actor Punishment | 2.311 | 3.55 | <.001 | 1.024 | 3.598 | |

| Time x Partner Punishment | 1.990 | 2.91 | .004 | .639 | 3.341 | |

| Time x Actor Reward | −.651 | −1.95 | .054 | −1.313 | .010 | |

| Time x Partner Reward | −.329 | −.98 | .331 | −.997 | .338 | |

Note. The table separates presentation of intercepts and slopes for ease of interpretation; all coefficients were included in the same model.

Alcohol consumption

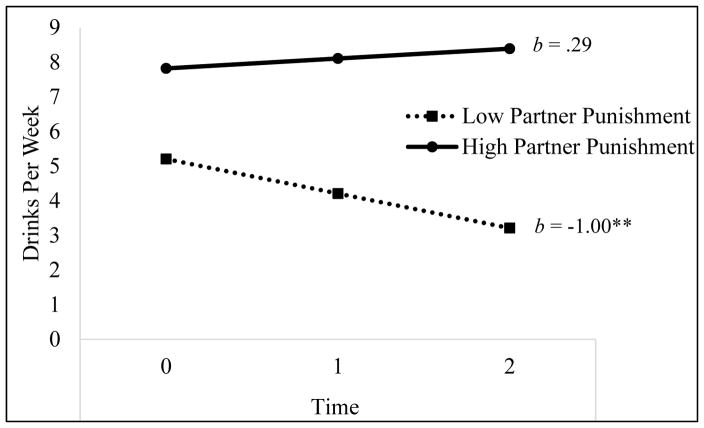

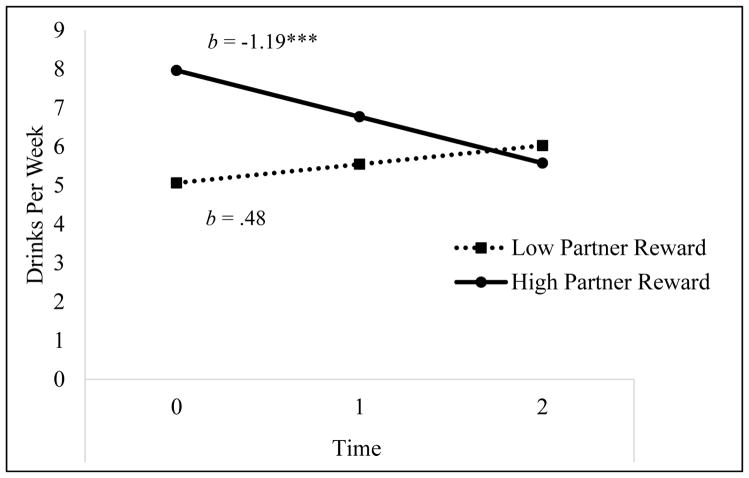

Results revealed a significant partner effect of punishment on the intercept of consumption, b=2.07, p=.042, suggesting that partner punishment was associated with heavier consumption at Time 0 (baseline). Additionally, a marginally significant time × partner punishment interaction, b=1.01, p=.055, suggested that changes in consumption over the six-month period varied as a function of partner punishment. Figure 1 presents consumption scores over time as a function of partner punishment. Simple slopes revealed that individuals with partners who reported lower levels (−1 SD) of punishment reported decreased consumption over time, b=−1.00, p=.009, whereas individuals with partners who reported higher levels (+1 SD) of punishment did not show changes in consumption over time, b=.29, p=497. Additionally, a significant time × partner reward interaction, b=−.74, p=.005, emerged. As can be seen in Figure 2, tests of simple slopes suggested that individuals with partners who reported higher levels (+1 SD) of reward reported decreased consumption over time, b=−1.19, p<.001, whereas individuals with partners reporting lower levels (−1 SD) of reward did not show changes in consumption over time, b=.48, p=.221. Thus, generally, those with partners who reported lower punishment and higher reward showed reduced consumption over the six-month period.

Figure 1.

Changes in alcohol consumption (DDQ scores) over six months as a function of partner punishment. ** p < .01

Figure 2.

Changes in alcohol consumption (DDQ scores) over six months as a function of partner reward. *** p < .001

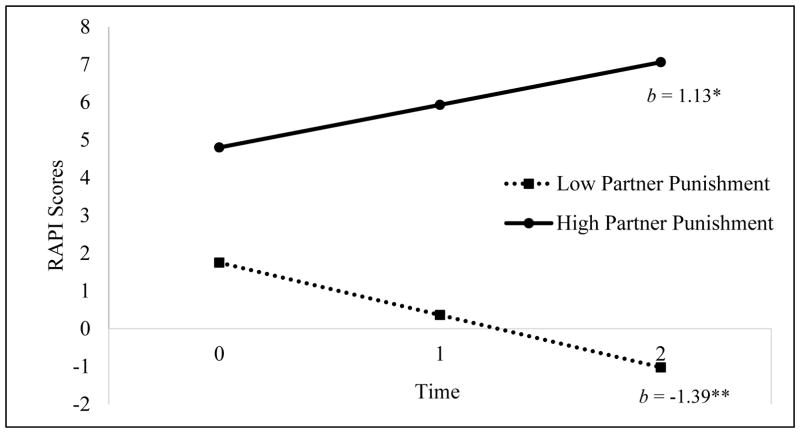

Negative alcohol-related consequences

Results with punishment revealed a significant partner effect of punishment on the intercept of consequences, b=2.41, p=.008, suggesting that partner punishment was associated with higher levels of negative alcohol-related consequences at Time 0 (baseline). Additionally, a significant interaction between partner punishment and time emerged, b=1.99, p=.004, suggesting that partner punishment was associated with increases in consequences over the six-month period. Figure 3 presents consequences scores over time as a function of partner punishment. Simple slopes revealed that individuals with partners who reported higher levels (+1 SD) of punishment reported increased levels of consequences over time, b=1.13, p=.050, whereas individuals with partners who reported lower levels (−1 SD) of punishment reported decreased levels of consequences over time, b=−1.389, p=.008.

Figure 3.

Changes in alcohol-related consequences (RAPI scores) over six months as a function of partner punishment. * p ≤.05 ** p < .01

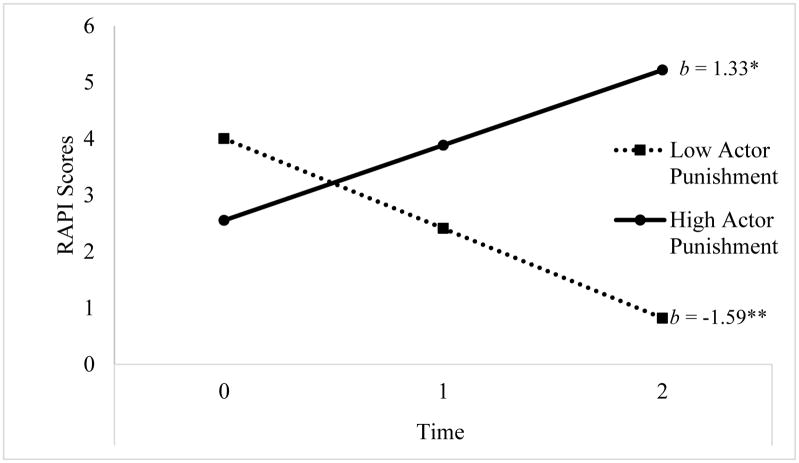

There was also evidence that actor punishment moderated the effect of time, suggesting that individuals who punished their partner for drinking reported higher levels of consequences themselves over time. As can be seen in Figure 4, results from simple slopes tests revealed that individuals who reported higher levels of punishment also showed increases in their own consequences over time, b=1.33, p=.017, whereas individuals who reported lower levels of punishment showed decreases in their own consequences over time, b=−1.59, p=.002.

Figure 4.

Changes in alcohol-related consequences (RAPI scores) over six months as a function of actor punishment. * p < .05 ** p < .01

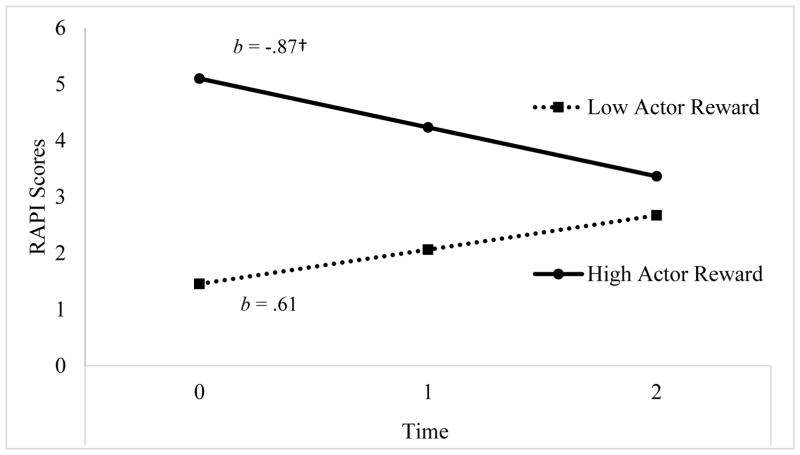

Finally, results with reward revealed a significant actor effect of reward on the intercept of consequences, indicating that rewarding one’s partner for nondrinking was associated with higher consequences at Time 0. Additionally, a marginal time × actor reward interaction emerged, b=−.65, p=.054, suggesting that rewarding one’s partner was associated with a marginal decrease in own consequences over time. This interaction is shown in Figure 5. Higher levels of reward were associated with a marginal decrease in consequences over time, b=−.867, p=.069, whereas low levels of reward were not associated with changes in consequences, b=.608, p=.259. Partner reward did not significantly predict the intercept or slope of consequences1.

Figure 5.

Changes in alcohol-related consequences (RAPI scores) over six months as a function of actor reward. † p < .10

Gender differences

We tested for gender differences in the intercept (i.e., baseline values) and slope (i.e., changes) of alcohol consumption and consequences, as well as actor and partner effects of regulation on the intercept and slope of consumption and consequences. Results from examination of the intercepts of consumption and consequences showed significant gender effects in the intercept of consumption (i.e., men reported greater baseline consumption than women), but no differences in consequences. Results examining changes in drinking suggested that changes in neither consumption nor consequences were different for men and women (ps>.25).

Second, we tested for gender interactions of the actor and partner effects of punishment and reward on the intercepts and slopes of drinking. Results showed that gender moderated the partner effect of punishment on the intercept of both consumption, b=4.36, p<.001, and consequences, b=2.00, p=.047. Decomposing these interactions revealed a similar pattern for consumption and consequences, such that partner punishment was associated with more consequences at baseline for men (consumption: b=5.81, p<.001; consequences: b=3.85, p=.004), but not for women (consumption: b=−2.91, p=.079; consequences: b=−.14, p=.924). In other words, husbands with wives who punished them reported higher levels of consumption and consequences at baseline, but the same was not true for husbands who punished wives. Additionally, gender moderated the partner effect of reward on the intercept of consumption, b=−1.08, p=.046, suggesting that with reward, wives with husbands who rewarded them reported greater consumption at baseline, b=2.24, p=.001, whereas the same was not true for husbands, b=.08, p=.927. Finally, gender did not moderate actor or partner effects of punishment or reward on changes in consumption nor consequences (ps>.15).

Patterns of covariance

A dyadic growth curve model has a variance-covariance matrix with four variances and six covariances. The variances reflect the variances of husband and wife intercept and slope and the covariances are represented by the covariance between husband and wife intercepts (i.e., degree of association between drinking consequences at Time 0 for husbands and wives), the covariance between husband and wife slopes (i.e., whether rate of change in one dyad member is similar to the rate of change in the other dyad member), and the correspondences between the intercepts and slopes, including two within-person covariances (i.e., within-person intercept and slope for husbands and wives; e.g., when husbands begin the study as lighter drinkers, does their own drinking change at a slower pace?) and two between-person covariances (i.e., intercept for one dyad member and slope for the other; e.g., when husbands start with lower consequences, do wives change their drinking at a slower pace?).

Results for random effects are presented in Table 4a for consumption and Table 4b for consequences. Results showed significant variability in intercepts and slopes for husbands and wives, denoted by significant random effects along the diagonals of Tables 4a and 4b. These effects indicate that spouses showed different levels of consumption and consequences at Time 0 as well as different rates of change in consumption and consequences over time. Additionally, results from the covariance matrix showed significant covariance in husband-wife intercept for consumption, suggesting that husbands and wives reported similar levels consumption at baseline. Results also showed significant covariance of the slopes for consequences, suggesting similarity in husband-wife change in consequences over time. For both outcomes, significant covariance in the female intercepts and slopes indicated that women who started out as heavier drinkers changed their rates of drinking at a slower pace. Moreover, for both outcomes, the residual variances for husbands and wives were significant, indicating variability in drinking unique to husbands and wives at a given time point. Finally, the residual covariance between husbands and wives was not significant for either outcome (ps>.35), suggesting that husband and wife consequence scores were not similar at a particular time point, after accounting for intercepts and slopes.

Table 4a.

Random Effects in the Dyadic Growth Curve (Outcome: Alcohol Consumption): Estimated G Covariance Matrix

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Male intercept | 43.86*** | |||

| 2. Female intercept | 12.96** | 29.41*** | ||

| 3. Male slope | 1.78 | 1.41 | 3.70** | |

| 4. Female slope | −.33 | −8.45*** | −.70 | 4.55*** |

Note.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Table 4b.

Random Effects in the Dyadic Growth Curve (Outcome: Alcohol-related Consequences): Estimated G Covariance Matrix

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Male intercept | 36.10*** | |||

| 2. Female intercept | −.67 | 23.28*** | ||

| 3. Male slope | −4.31 | −.10 | 4.81* | |

| 4. Female slope | −3.27 | −.12.55*** | 5.30** | 15.84*** |

Note.

p < .05

p < .001

Discussion

Alcohol problems have significant adverse effects on relationship outcomes (e.g., Homish, Leonard, & Kearns-Bodkin, 2006; Leonard & Eiden, 2007; Levitt & Cooper, 2010; McCrady, Epstein, & Kahler, 1998). It is not surprising that spouses in relationships where their partner’s drinking is seen as problematic attempt to change the drinking habits (Rodriguez et al., 2013). Thus, it is important to consider regulation strategies from a dyadic perspective, which takes both spouses’ regulation strategies and both spouses’ drinking behaviors into consideration at the same time. The present research extended previous work by more closely considering the effectiveness of regulation strategies in reducing one’s partner’s drinking and related consequences over time in a sample of non-treatment-seeking married couples. Furthermore, the dyadic approach allowed a simultaneous examination of the effects of each partner’s regulation strategies on each partner’s changes in drinking and consequences. Results showed that punishing a partner for drinking is an unsuccessful strategy for reducing consumption and consequences, and was instead associated with increases in alcohol-related consequences over time. Conversely, using lower levels of punishing behaviors was associated with reductions in partner-reported consumption and consequences, and using higher levels of positive reinforcement (i.e., rewarding nondrinking) was associated with reductions in consumption over time. These effects were not different for husbands and wives. Our results are consistent with and contribute to the literature regarding how punishing social control strategies actually do much more harm than good (e.g., Craddock et al., 2015; Lewis & Rook, 1999; Okun et al., 2007).

Results examining concurrent (i.e., simultaneous) partner effects of regulation on drinking showed that use of punishing strategies was associated with greater concurrent partner drinking and consequences. However, a closer look into gender moderation analyses revealed that this effect of punishment was only concurrently associated with heightened drinking and consequences for men. That is, wives who used more punishing strategies had husbands who reported greater consumption and consequences. Previous work has shown gender differences in social control behaviors, such that women are more likely than men to try to control their partner’s behavior (Umbertson, 1992); these results are consistent in demonstrating that wives were using punishment in response to their husbands’ heightened drinking, at least at baseline. These results are also consistent with findings from Raitasalo and Holmila’s (2005) examination of social control and heavy drinking, in which heavy drinking husbands were likely to have partners who tried to influence them to drink less, but wives who experienced concerns about their own drinking did not necessarily have spouses who attempted to control it.

Other interesting trends emerged with actor effects, both concurrently and over time. Concurrently, the actor effect of reward suggested that positively reinforcing partners for nondrinking was associated with greater consequences at baseline. This unpredicted finding, coupled with the marginally significant interaction between actor reward and time, may partially be explained as regression to the mean. Additionally, perhaps individuals who report more consequences themselves enact the regulatory strategies they would prefer their partners to use on them – in this case, rewarding sobriety.

Continuing to examine actor effects longitudinally, the use of punishment strategies to change a partner’s drinking was associated with increases in own alcohol-related consequences, whereas the use of reward (i.e., people who are trying to regulate their partner’s drinking in a positive or constructive way) was associated with decreases in own consequences over time. Conversely, the longitudinal actor effect of punishment showed that people who punished their partners actually experienced more consequences themselves over time. This effects might be explained because it is difficult to positively reinforce a partner’s nondrinking while also experiencing consequences oneself, whereas punishing partners might create a cycle of negative affect that can be coped with by drinking.

In understanding why partner punishment is associated with increases in alcohol-related consequences over time, it helps to consider how both partners may be feeling and how the punishing behaviors may be communicated to the drinker. There is considerable frustration in a situation where one’s partner is drinking more than desired and one feels limited control in their ability to affect this person’s behavior. Punishing strategies likely result as a function of this frustration. Although the goal is to change the partner’s behavior, the way partners attempt to reach the goal is likely influenced by their own frustration. In other words, punishment in general is often a combination of an expression of anger as well as a hope for rehabilitation. Rewarding strategies do not have the same mixture of motives. Understanding how frustration plays a role in regulation strategies—and subsequent focus on reducing both frustration and confrontational strategies—is critical to developing and improving couples-based interventions in the future. Work from Kahler et al. (2003) supports this notion—they found that higher psychological distress was associated with higher use of attempts to confront and control the partner’s drinking, suggesting that these more aggressive coping attempts may reflect increasing desperation. Conversely, couples who were less psychologically distressed used strategies that positively reinforced sobriety more often relative to other coping behavior.

Results presented here are echoed in current approaches to individual and couples therapy for alcohol abuse and dependence. Partners play an important role in getting the drinker involved in treatment (Hasin, 1994; Polcin & Weisner, 1999). Some of the prominent treatment models for change in addictive behaviors—community reinforcement approach and family training (CRAFT), contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy—all note that if the goal is to change a person’s behavior, strategies that are effective for that person must be adopted. Punishing strategies tend to leave more space for conflict, and our results suggest that these are counterproductive to efforts to reduce drinking. CRAFT’s rather simple underlying philosophy is to make abstinence more rewarding for the drinker than drinking. Enhancing positive reinforcement of sobriety and reducing positive reinforcement for drinking focuses on rewards, because on a fundamental level, rewarding and punishing behaviors are exactly that, rewarding and punishing.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this research presents a new way of examining regulation attempts on changes in partner drinking among non-treatment-seeking couples, it should be considered in light of limitations. First, the sample was comprised of one spouse who was an undergraduate student; usually, their spouse was not a student. The university at which this data was collected is a larger, urban, commuter university, wherein students are older and more likely to hold full-time jobs than at traditional universities. Nonetheless, the type of sample limits generalizability from which conclusions can be drawn. Second, attrition was relatively high in this sample. The inclusion criteria and limited participant payment ($15 per couple per timepoint) were both due to this project’s data collection stemming from a graduate student training grant. Finally, participants did not need to be heavy drinkers to participate in this study; many couples did not report hazardous drinking levels. Future research would benefit from an examination of partner regulation strategies in a more targeted sample wherein at least one partner’s alcohol use is considered a source of strain in the relationship. Although the current research provides an initial glance into this complex dyadic process, it is in couples who are struggling with problematic drinking where these issues most clearly emerge. We would expect the partner effects shown here to be stronger among couples presenting with more severe drinking patterns (i.e., alcohol abuse and dependence).

In conclusion, the current study sheds light onto partner regulation strategies and provides evidence that punishment is unsuccessful at changing a partner’s drinking; in fact, punishment is associated with increased partner alcohol-related consequences over time. Future targeted indicated prevention treatment approaches may wish to isolate strategies that are especially effective (and ineffective) and relay the relative success (and failure) of these strategies to concerned others, with the common goal of reducing hazardous drinking and related consequences.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant F31AA020442.

Footnotes

The current analysis plan treats punishment and reward as time-invariant because we were interested in how punishment at one time (i.e., Time 0 or baseline) influenced changes in drinking. However, we also ran a model utilizing punishment and reward as time-varying predictors. Results were similar with two exceptions. The partner effect of punishment on the intercept was no longer significant; the partner effect of punishment on the slope (the primary analysis of interest) remained significant. Additionally, the previously marginal actor reward × time interaction for alcohol-related consequences was significant in this model, b = −1.007, p = .002, suggesting that reward was associated with decreases in own consequences over time.

References

- Amato PR, Previti D. People’s reasons for divorcing gender, social class, the life course, and adjustment. Journal of Family Issues. 2003;24(5):602–626. doi: 10.1177/0192513X03254507. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asher RM. Women with alcoholic husbands: Ambivalence and the trap of codependency. University of North Carolina Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete EM, Stephens MAP, Druley JA, Greene KA. Effects of spousal control and support on older adults’ recovery from knee surgery. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20(2):302–310. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.302. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer JL, Fitzpatrick J, Cleveland B, Lee JM, McKnight A, Miller B. Binge drinking in the context of romantic relationships. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(8):1496–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Bouma R, Kelly A, Young RM. Individual psychopathology and marital distress Analyzing the association and implications for therapy. Behavior Modification. 1999;23(2):179–216. doi: 10.1177/0145445599232001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halford WK, Price J, Kelly AB, Bouma R, Young RM. Helping the female partners of men abusing alcohol: a comparison of three treatments. Addiction. 2001;96(10):1497–1508. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.9610149713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS. Treatment/self-help for alcohol-related problems: relationship to social pressure and alcohol dependence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55(6):660–666. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.660. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1994.55.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemström Ö. Alcohol-related deaths contribute to socioeconomic differentials in mortality in Sweden. The European Journal of Public Health. 2002;12(4):254–262. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/12.4.254. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/12.4.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmila M. Wives, husbands and alcohol: A study of informal drinking control within the family. Vol. 36. Alcohol Research Documentation Incorporated; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Holmila M, Mustonen H, Rannik E. Alcohol use and its control in Finnish and Soviet marriages. British Journal of Addiction. 1990;85(4):509–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish GG, Leonard KE, Kearns-Bodkin JN. Alcohol use, alcohol problems, and depressive symptomatology among newly married couples. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83(3):185–192. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvinen M. Controlled controllers: Women, men, and alcohol. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1991;18:389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, McCrady BS, Epstein EE. Sources of distress among women in treatment with their alcoholic partners. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24(3):257–265. doi: 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Eiden RD. Marital and family processes in the context of alcohol use and alcohol disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:285–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Jacob T. Alcohol, alcoholism, and family violence. Handbook of Family Violence. 1988:383–406. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-5360-8_16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Alcohol and premarital aggression among newlywed couples. Journal of Studies on Alcohol, Supplement. 1993;(11):96–108. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.96. http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.96. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Leonard KE, Senchak M. Prospective prediction of husband marital aggression within newlywed couples. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(3):369–380. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.105.3.369. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A, Cooper ML. Daily alcohol use and romantic relationship functioning: Evidence of bidirectional, gender-, and context-specific effects. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010;36(12):1706–1722. doi: 10.1177/0146167210388420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control in personal relationships: impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18(1):63–71. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund R, Christensen U, Nilsson CJ, Kriegbaum M, Rod NH. Stressful social relations and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2014;68(8):720–727. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, McKay JR, O’Farrell TJ. Twelve-month abstinence from alcohol and long-term drinking and marital outcomes in men with severe alcohol problems. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59(5):591–598. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.591. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1998.59.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP. For better or for worse? The effects of alcohol use on marital functioning. Clinical Psychology Review. 2003;23(7):959–997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS. Treating alcohol problems with couple therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68(5):514–525. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Kahler CW. Families of alcoholics. Comprehensive Clinical Psychology. 1998;9:199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Andrews NR, Wilbourne P, Bennett ME. A wealth of alternatives: Effective treatments for alcohol problems. In: Miller WR, Heather N, editors. Treating Addictive Behaviors: Processes of Change. 2. New York: Plenum Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CM, O’Farrell TJ. Factors associated with marital aggression in male alcoholics. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8(3):321–335. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.8.3.321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okun MA, Huff BP, August KJ, Rook KS. Testing hypotheses distilled from four models of the effects of health-related social control. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2007;29(2):185–193. doi: 10.1080/01973530701332245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJ, Simpson JA. Helping each other grow: Romantic partner support, self-improvement, and relationship quality. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0146167210383045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall NC, Fletcher GJ, Simpson JA. Regulation processes in intimate relationships: the role of ideal standards. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(4):662–685. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philpott H, Christie MM. Coping in male partners of female problem drinkers. Journal of Substance Use. 2008;13(3):193–203. doi: 10.1080/14659890701682345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polcin DL, Weisner C. Factors associated with coercion in entering treatment for alcohol problems. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;54(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raine P. Women’s perspectives on drugs and alcohol: The vicious circle. Ashgate Pub Ltd; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Raitasalo K, Holmila M. The role of the spouse in regulating one’s drinking. Addiction Research & Theory. 2005;13(2):137–144. doi: 10.1080/16066350512331328140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, DiBello AM, Neighbors C. Perceptions of partner drinking problems, regulation strategies and relationship outcomes. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(12):2949–2957. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez LM, DiBello AM, Wickham R. Regulation strategies mediate associations between heavy drinking and relationship outcomes in married couples. Addictive Behaviors. 2016;54:64–69. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Room R, Greenfield TK, Weisner C. People who might have liked you to drink less: Changing responses to drinking by US family members and friends, 1979–1990. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1991;18:573–596. [Google Scholar]

- Rotunda RJ, Doman K. Partner enabling of substance use disorders: Criticalreview and future directions. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2001;29(4):257–270. doi: 10.1080/01926180126496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas EJ, Ager RD. Unilateral family therapy with spouses of uncooperative alcohol abusers. Treating Alcohol Problems: Marital and Family Interventions. 1993:3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Anders SL. Social control of health behaviors in marriage. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2001;31(3):467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson D. Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science & Medicine. 1992;34(8):907–917. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90259-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman JP. The other half: Wives of alcoholics and their social-psychological situation. Aldine de Gruyter; Hawthorne, NY: 1991. [Google Scholar]