Abstract

Negative attitudes of heterosexual people toward same-sex marriage relate to the degree to which they are homophobic. However, it has been understudied whether there exists a gender difference in this association. Our results indicated that homophobia was the best predictor of attitudes toward gay male and lesbian marriage, and this was equally true for both heterosexual men and women. However, the attitudinal difference between gay male and lesbian marriage was related to homophobia in men but not in women. That is, for men only, being less homophobic towards lesbians than towards gay men was associated with favoring lesbian over gay men marriage. Considering these results, the role of gender in attitudes toward same-sex marriage seems to be as an important moderator of homophobia.

Keywords: Gay marriage, lesbian marriage, homophobia, gender, negative attitudes, attitude differences, heterosexual attitudes, attitude strength, same-sex marriage

INTRODUCTION

Several studies suggest that homophobic individuals hold stereotypes of gays and lesbians and thus, dislike them (e.g., Dowsett, 1993; Gentry, 1987; Herek, 1987, 2002; Raja & Stokes, 1998). Negative stereotypical thoughts arise from proximity and social knowledge of outgroups (Zajonc, Shaver, Tavria, & van Kneveld, 1972); and in the case of heterosexual-homosexual dynamics, they may also serve as a safety mechanism used to enforce group superiority and normalcy (Kristiansen, 1990). Research consistently shows men to be more homophobic than woman (e.g., Raja & Stokes; Gough, 2002; Herek, 2002). Heterosexual positions regarding same-sex marriage are also related to the degree to which an individual is homophobic (Bolte, 1998). However, the interplay between gender, homophobia, and attitudes of heterosexual people towards gay male and lesbian marriage are largely unknown. Furthermore, it is not known whether heterosexual men and women differentiate between attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage as separate types of marriage. The present study attempts to address these issues. Possible outcomes may help to understand whether specific combinations of gender and homophobia are especially prone to increased negative attitudes towards same-sex marriage.

As previously stated, heterosexual females are substantially more understanding and compassionate of gays and lesbians than are heterosexual males (Herek, 2002; Raja & Stokes, 1998). They are more likely to be proponents of employment, adoption, and civil rights and less likely to hold negative stereotypical beliefs about the population. Heterosexual men are least supportive of these same aspects. These men are more likely to believe that homosexuals are mentally ill, sexual predators or child molesters, and generally more likely to fit negative stereotypical preconceptions (Herek, 2002).

There is also a heterosexual gender difference in the attitudes (other than explicit homophobia) held towards equal rights for gay men versus for lesbians (Kite & Whitley, 1996). Heterosexuals, especially men, are more supportive of affording lesbians civil and adoption rights relative to extending them to gay men (Herek, 2002). This may be because there is a widespread belief that gay men are more socially and sexually deviant than their female counterparts (Dowsett, 1993). This may also be because heterosexual men in particular believe that gay men have more atypical gender roles (Gough, 2002; Madon, 1997). And this violation of gender roles may not only explain why heterosexual men are less inclined towards giving gay men equal rights, but in general, less likely to hold favorable attitudes towards gay men than lesbians (Dowsett; Madon; Risman & Schwartz, 1988).

The previously mentioned research indicates that heterosexual men are, on average, more homophobic than heterosexual women. Furthermore, homophobia and other attitudes towards homosexual individuals (such as opinions about their legal rights) are highly related (Bolte, 1998); and recent research suggests that heterosexual men and women differ in their attitudes towards same-sex marriage (Lannutti & Lachlan, in press). Whether this gender difference is simply accounted for by different degrees of homophobia, or whether gender moderates the relationship between homophobia and attitudes towards same-sex marriage is largely unknown. Furthermore, differences in homophobia towards gay men versus lesbians, and their effects on heterosexual attitudes towards same-sex marriage are also largely unknown. The following hypotheses aim to extend and further explore the influence of gender and homophobia on heterosexual attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage:

(H1) Heterosexual men have, in general, more negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage than heterosexual women do.

(H2) Heterosexual men may have more negative attitudes towards gay male marriage than marriage between lesbians; this negative pattern may be less pronounced among heterosexual women.

(H3) Differences in homophobia may explain gender differences in attitudes towards same-sex marriage. However, gender may also have moderating effects on the relationship of homophobia with attitudes.

METHODS

Participants and Procedure

We offered communication studies undergraduate students research credit to complete an online survey on Experimentrak. Participants took the survey either on a home computer or school computer. Participants were told this was a study on attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage, and explicit instructions were given throughout the survey.

We collected data from 161 undergraduates. Table 1 shows the distributions of the four main demographic variables for the sample: ethnicity, family income, gender and age. About two-thirds of the sample was White, one-quarter Black or Asian. Most participants reported a family income of $100K or above. There were more female participants than male. Most participants were 19 years old.

Table 1.

Description of the demographic variables

| Demographic & Independent | VARIABLES | n | % of N | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 108 | 67.1 | ||||

| Black | 19 | 11.8 | ||||

| Latino | 6 | 3.7 | ||||

| Asian | 19 | 11.8 | ||||

| Indian | 4 | 2.5 | ||||

| Other | 5 | 3.1 | ||||

| Income (USD) | ||||||

| $10K - $30K | 4 | 2.5 | ||||

| $31K - $50K | 9 | 5.6 | ||||

| $51K - $75K | 27 | 16.8 | ||||

| $76K - $100K | 37 | 23.0 | ||||

| $101K - $250K | 55 | 34.2 | ||||

| $251K + | 29 | 18.0 | ||||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 106 | 65.8 | ||||

| Male | 55 | 34.2 | ||||

| M | SD | Range | ||||

| Age | 19.17 | 1.08 | 17 – 23 | |||

Measures

Homophobia

To assess homophobia in heterosexual individuals, we used the Attitudes Towards Lesbians Scale (α = .86), and the Attitudes Towards Gay Men Scale, α = .91 (Herek, 1987). Individuals were asked to agree with statements using a five-point scale. We will refer to these as lesbian homophobia (M = 1.97, SD = .75) and gay male homophobia (M = 2.17, SD = .91) in proceeding sections. An item from the lesbian homophobia scale was “Lesbians are sick,” and from the gay male homophobia scale, “I think male homosexuals are disgusting.” For both of these scales, a score of five represented a highly homophobic individual.

Attitudes towards same-sex marriage

To assess perceptions about same-sex marriage, we used a version of Lannutti and Lachlan's (in press) five-point Attitude towards Same-Sex Marriage Scale. We ran it twice, once using “gay male couples” (α = .97), and once using “lesbian couples” (α = .96) in lieu of “same-sex couples” (lesbian: M = 2.09, SD = .82; gay male: M = 2.14, SD = .91). An example for the attitudes towards gay male marriage scale was, “I would be happy if gay male couples were allowed to marry” (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree). The lesbian version of the scale would thus use “lesbian” instead of “gay male” for each item's direct object.

Social desirability

To control for the tendency to respond in a socially desirable fashion, respondents completed the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability scale (1960; α = .75). An example was, “I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable.” Respondents rated their agreement on a 5-point scale, where a score of one suggested an individual was strongly concerned with being socially desirable, and a score of five indicated an individual was not at all concerned with social desirability (M = 3.11, SD = .32).

Statistical Methods

The sample used in our study was admittedly not random; yet for the following analyses, the statistics used treated it as if it were. Most statistical tests and methods (e.g., t-tests, regressions) are based on the assumption that a given sample is random. And though it has become commonplace and widely accepted to use statistical tests that are best suited for random samples on any sample at all, we would be remiss not to make this concession. As such, the data were analyzed using independent sample t-tests and multiple linear regression analyses. For interaction terms, we used moderated regression models in which variables were entered on separate steps, with social desirability entered before the independent variable, differences in homophobia, and the moderator variable, gender (Aiken & West, 1991). The interaction term (created by the independent variable being multiplied by the moderator) was entered last.

RESULTS

(H1) We first tested whether heterosexual men had, in general, more negative attitudes toward same-sex marriage than did heterosexual women. Men (M = 2.55, SD = .96) were more likely than women (M = 1.90, SD = .77) to hold negative attitudes towards gay male marriage, t(159) = 4.82, p < .001, d = .77. Men (M = 2.40, SD = .85) were also more likely than women (M = 1.93, SD = .76) to hold negative attitudes towards lesbian marriage t(159) = 3.56, p < .001, d = .56. Thus, these results confirmed previous research, which suggested that men and women ultimately differ with respect to same-sex marriage.

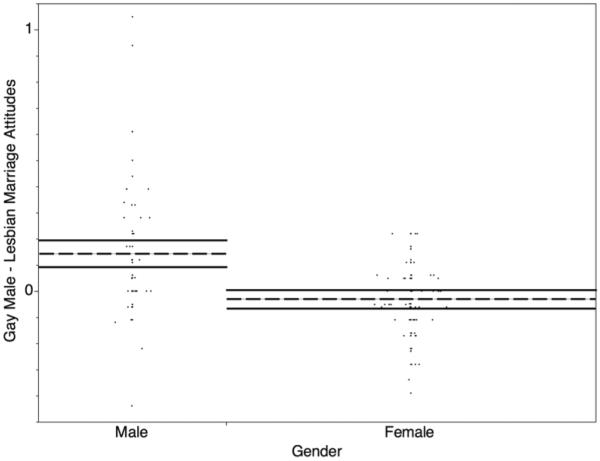

(H2) To test if heterosexual men would show more negative attitudes towards gay male versus lesbian marriage than heterosexual women, we created a new variable—gay male marriage attitudes subtracted by lesbian marriage attitudes. Thus, positive scores indicated favoring lesbian marriage over gay male marriage, and negative scores indicated favoring gay male marriage over lesbian marriage (M = .04, SD = .26). Men (M = .14, SD = .26) were more likely than women (M = −.03, SD = .13) to differentiate between gay male and lesbian marriage, t(159) = 5.20, p < .001, d = .74; Figure 1 illustrates that men, more than women, preferred lesbian marriage to gay male marriage.

Figure 1.

Differences in attitudes between gay male and lesbian marriage by heterosexual gender: The y-axis scale is based on a contrast score of attitudes towards gay male minus lesbian marriage. A score of 1 signifies a preference for lesbian marriage, a score of -1, for gay male marriage, and 0 signifies neither a preference for gay male nor lesbian marriage. Horizontal solid bars represent 95% confidence intervals of the means, and the dashed lines signify the means themselves.

(H3) Since gender and homophobia are related, as are homophobia and attitudes towards same-sex marriage, it was posited that differences in homophobia might explain gender differences in attitudes towards same-sex marriage. However, gender may also have moderating effects on the relationship of homophobia with attitudes.

Before investigating our hypothesis we assessed gender differences in homophobia. Corresponding to previously mentioned results, we found a gender difference with respect to gay male and lesbian homophobia. Men (M = 2.66, SD = .91) were more likely than women (M = 1.90, SD = .76) to be more homophobic towards gay men, t(159) = 5.82, p < .001, d = .94. Men (M = 2.29, SD = .80) were also more homophobic than women (M = 1.80, SD = .66) towards lesbians, t(159) = 4.12, p < .001, d = .67. Given the similarities with the above results on gender and attitudes towards same-sex marriage, it seemed possible that different degrees of homophobia mediated gender differences in attitudes. However, gender might also moderate the effect of homophobia on the attitudes. In other words, heterosexual men and women might substantially differ in the relationship between homophobia and attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage.

We used multiple regression analyses to test these possibilities. In all models we statistically controlled for social desirability. The first analysis assessed the effects of gender and gay male homophobia on attitudes towards gay male marriage. Gender was entered one step earlier than gay male homophobia and the interaction term of gender multiplied by homophobia was entered last. Gender was not a significant predictor (t(155) = −.26, p = .42, ß = −.03, ΔR2 < .01), nor was there a significant interaction (t(155) = .40, p = .69, ß = .01, ΔR2 < .01). Gay male homophobia strongly predicted negative attitudes toward gay male marriage (t(155) = 24.69, p < .001, ß = .92, ΔR2 = .70). Thus, it seemed that the effect of gay male homophobia mediated the effect of gender, and gender did not moderate homophobia.

A corresponding model was used for explaining attitudes towards lesbian marriage. Again, gender failed to achieve significance as a predictor (t(155) = −.33, p = .74, ß = −.01, ΔR2 < .01), and did not moderate homophobia (t(155) = −.45, p = .65, ß = .01, ΔR2 < .01). Lesbian homophobia contributed significantly to the model (t(155) = 27.84, p < .001, ß = .92, ΔR2 = .76). The more homophobic individuals were of lesbians, the more negative attitudes they would hold towards lesbian marriage. Thus with respect to attitudes towards both gay and lesbian same-sex marriage, it seemed that all initially found gender differences could be explained by homophobia, and homophobia was ultimately a mediator of gender on attitudes towards both gay male and lesbian marriage. Gender did not moderate these effects.

We then analyzed whether the found gender differences in attitudes towards gay male versus lesbian marriage (see results above – H2) were either mediated or moderated by gender differences in homophobia towards gay men versus lesbians. Homophobia was constructed using contrast scores of gay male homophobia subtracted by lesbian homophobia. Positive scores indicated more homophobia towards gay men than lesbians, and negative scores indicated more homophobia towards lesbians (M = .20, SD = .46).

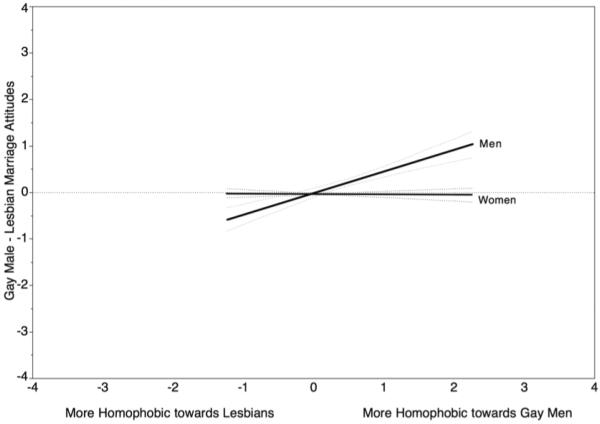

The gay male v lesbian marriage scale (described under H2) was regressed by social desirability, gender, the homophobia differential scale just defined, and the interaction term of gender multiplied by said homophobia differential scale. Initially, gender produced a main effect where men favored lesbian marriage over gay male marriage (t(155) = 4.04, p < .001, ß = .28, ΔR2 = .10); however gender further moderated homophobia differences, (t(155) = 4.67, p < .001, ß = .31, ΔR2 = .07). The data were split by gender to illustrate this interaction. As shown in Figure 2, for heterosexual men, being more homophobic towards gay men versus lesbians was strongly related to differences in attitudes favoring lesbian marriage (t(52) = 6.06, p < .001, ß = .65, R2 = .28). For heterosexual women, there was no association between preferring gay men or lesbians and differences in attitudes between types of same-sex marriage (t(103) = −.26, p < .79, ß = −.03, ΔR2 < .01). Overall, it seemed that homophobia was not simply a mediator of heterosexual attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage, but could be moderated by gender in some instances.

Figure 2.

Gay male and lesbian homophobia differences predicting same-sex marriage attitudinal differences by gender. Note the x-axis represents negative attitudinal discrimination between gay male and lesbians, and the y-axis represents gay male marriage attitudes minus lesbian marriage attitudes. Positive numbers represent a preference for lesbian marriage, and negative numbers represent a preference for gay male marriage.

DISCUSSION

Men initially seemed to more negatively judge same-sex marriage, thereby confirming our first hypothesis. And confirming the second hypothesis, men were also more likely to discriminate between the two sorts of marriage, favoring the lesbian group. Regarding the third hypothesis, heterosexual male attitudes were not significantly different than female attitudes when controlling for homophobia, however, there was a substantial sex difference in the association between homophobia and attitudes: Heterosexual men, but not heterosexual women, were more likely to favor lesbian marriage over gay male marriage if they were also less homophobic against lesbians than gay men.

Homophobia seemed to be the most influential variable with respect to attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage. However, the contributions of gender towards these attitudes should not be diminished, especially when discussing the differentiation between types of marriage. Men showed a clear preference for lesbian marriage over gay male marriage in general; and this was further moderated by their homophobic beliefs towards gay men versus lesbians. The reason for these associations may be partially due to the gender role violations perceived more strongly in heterosexual men regarding their homosexual counterparts (Dowsett, 1993; Madon, 1997; Risman & Schwartz, 1988). Alternatively, or in addition, it may also be due to heterosexual men valuing lesbian relationships as erotic and exciting, and gay male relationships as unerotic and revolting (Louiderback & Whitley, 1997; Renaud & Byers, 2001).

The heterosexual female trend towards not differentiating between the types of marriage might be a function of women's low differentiation in homophobia towards gay male and lesbians. Or it might be that heterosexual women, in contrast to heterosexual men, neither sexualize nor asexualize gay male and lesbian relationships. For example, there is strong evidence that heterosexual men are especially sexually aroused by lesbian pornography while their female counterparts are less aroused by pornography of any sort (e.g., Louiderback & Whitley, 1997; Murnen & Stockton, 1997; Steele & Walker, 1974). The dissociation of sexual arousal from other impressions might allow women to hold more unbiased attitudes towards gay men relative to lesbians (and vice versa). Regardless of the explanation, the moderating effects of gender on homophobia extend what is currently understood about heterosexual attitudes by showing yet another instance in which heterosexual women are more tolerant and heterosexual men, more extreme towards homosexuals, and in particular, gay men.

Our current research has important implications for both gay rights activism and society at large—particularly if both lesbian and gay male marriages are to ever be legally granted. The concept of same-sex marriage should not be considered as indivisible when describing unions between homosexual individuals in either research or debate. Activists who fight for such rights, who lump lesbian marriage with gay male marriage ignore an important distinction that the heterosexual men, who so often are responsible for granting such rights, most likely, do not ignore. And that distinction is gender. That is, and the data largely support this, if there were only lesbians asking for the right to marry, heterosexuals and particularly heterosexual men would most likely be amenable to the request.

Advocates for gay marriage must recognize that heterosexual attitudes vary with regard to gay male marriage relative to lesbian marriage. The resistance is likely to be much greater for the former than latter. Hence, advocates may have to adapt their rhetorical strategies when lobbying for their cause. For example, when advocating for gay marriage, they may provide numerous examples of lesbian couples that have long-term successful and functioning relationships. However, although focusing on the type of gay marriage for which there is more support, it does not directly address the type for which our results show there is greater resistance. Alternatively, advocates may directly address resistance to gay male marriage by showing examples of long-term functioning male relationships that directly contradict stereotypes. The persuasiveness of the two approaches has not yet been determined and constitutes an important issue for future research.

Limitations

The current research had two main limitations. The generalizability of the sample remained questionable. Though we were using a large enough sample, it was still principally comprised of White, affluent undergraduates. Their attitudes and beliefs were likely to differ from those of lesser socioeconomic status, those who had experienced more in years, and those of lesser educational attainment. Also, these were unmarried students. Married and divorced individuals may have different opinions about gay male and lesbian marriage because of their experiences with the institution itself.

Also, we were limited by our adapting of measures. We used established scales where possible for this research; however in some measures, we needed to change some of the words to suit our research questions. For example, in adapting the Attitude towards Same-Sex Marriage Scale (Lannutti and Lachlan, in press), we were forced to change “same-sex couples” into gay male couples and lesbian couples in order to assess the role of homosexual gender over heterosexual, same-sex marriage attitude strength. Though reliability maintained quite strong, and though their correlations with homophobia indicated good convergent validity, future research should further assess the validity of these adapted scales.

Future Research

Attitudes towards same-sex marriage may become progressively more positive—much in the same way that homophobic attitudes, over the past few decades, have attenuated (Newport, 2001). Future research might find the other variables aside from homophobia that influence heterosexual attitudes towards gay male and lesbian marriage. These variables might include socioeconomic status, heterosexual marital success, current relationship satisfaction, or positive sexual cognitions held towards gay men and lesbians. Researchers might also endeavor to understand why men differentiate between types of marriages and women ultimately do not. And finally, further studies might evaluate why many heterosexuals themselves feel uneasy, hesitant, and even threatened when asked to share the title of “marriage” with homosexual men and women. Once those have been realized, gays and lesbians may use that knowledge to further the acquisition of equal rights, and be closer towards actualizing marriage, as heterosexuals know it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Preparation of this manuscript was supported, in part, by center grant P30-MH52776 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by NRSA postdoctoral training grant T32-MH19985.

REFERENCES

- Bolte A. Do wedding dresses come in lavender? The prospects and implications of same-sex marriage. Social Theory and Practice. 1998;24:111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett GW. I'll show you mine, if you'll show me yours: Gay men, masculinity research, men's studies, and sex. Theory and Society. 1993;22:69–709. [Google Scholar]

- Gentry CS. Social distance regarding male and female homosexuals. Journal of Social Psychology. 1987;127:199–208. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1987.9713680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gough B. `I've always tolerated it but…': Heterosexual masculinity and the discursive reproduction of homophobia. In: Coyle A, Kitzinge C, editors. Lesbian and Gay Psychology: New Perspectives. BPS Blackwell; Oxford, England: 2002. pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Religious orientation and prejudice: A comparison of racial and sexual attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1987;12:34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. Gender gaps in public opinion and lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2002;66:40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kite ME, Whitley BE. Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behaviors, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1996;22:336–353. [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen CM. The symbolic/value-expressive function of outgroup attitudes among homosexuals. The Journal of Social Psychology. 1990;130:61–69. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1990.9922934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lannutti PJ, Lachlan KA. Assessing attitudes toward same-sex marriage: Scale development and validation. Journal of Homosexuality. doi: 10.1080/00918360802103373. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louiderback A, Whitley BE. Perceived erotic value of homosexuality and sex-role attitudes as mediators of sex differences in heterosexual college students' attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. The Journal of Sex Research. 1997;34:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Madon S. What do people believe about gay males? A study of stereotype content and strength. Sex Roles. 1997;37:663–685. [Google Scholar]

- Marlowe D, Crowne DP. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murnen SK, Stockton M. Gender and self-reported sexual arousal in response to sexual stimuli: A meta-analytic review. Sex Roles. 1997;37:135–153. [Google Scholar]

- Newport F. American attitudes towards homosexuality continue to become more tolerant. 2001 Retrieved: November 1, 2007. from http://www.gallup.com/poll/4432/American-Attitudes-Toward-Homosexuality-Continue-Become-More-Tolerant.aspx.

- Raja S, Stokes JP. Assessing attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: The modern homophobia scale. Journal of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Identity. 1998;3:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Renaud CA, Byers ES. Positive and negative sexual cognitions: Subjective experience and relationships to sexual adjustment. The Journal of Sex Research. 2001;38:252–262. [Google Scholar]

- Risman B, Schwartz P. Sociological research on male and female homosexuality. Annual Review of Sociology. 1988;14:125–147. [Google Scholar]

- Steele DG, Walker CE. Male and female differences in reaction to erotic stimuli as related to sexual adjustment. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 1974;3:459–470. doi: 10.1007/BF01541166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc RB, Shaver P, Tavria C, van Kneveld D. Exposure, satiation and stimulus discriminability. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1972;21:270–280. doi: 10.1037/h0032357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]