Abstract

CD4+ T cells in female MRL+/+ mice exposed to solvent and water pollutant trichloroethylene (TCE) skew toward effector/memory CD4+ T cells, and demonstrate seemingly non-monotonic alterations in IFN-γ production. In the current study we examined the mechanism for this immunotoxicity using effector/memory and naïve CD4+ T cells isolated every 6 weeks during a 40 week exposure to TCE (0.5 mg/ml in drinking water). A time-dependent effect of TCE exposure on both Ifng gene expression and IFN-γ protein production was observed in effector/memory CD4+ T cells, with an increase after 22 weeks of exposure and a decrease after 40 weeks of exposure. No such effect of TCE was observed in naïve CD4+ T cells. A cumulative increase in DNA methylation in the CpG sites of the promoter of the Ifng gene was observed in effector/memory, but not naïve, CD4+ T cells over time. Also unique to the Ifng promoter was an increase in methylation variance in effector/memory compared to naïve CD4+ T cells. Taken together, the CpG sites of the Ifng promoter in effector/memory CD4+ T cells were especially sensitive to the effects of TCE exposure, which may help explain the regulatory effect of the chemical on this gene.

Keywords: trichloroethylene, next-generation sequencing, epigenetics, immunotoxicity, CD4+ T cells

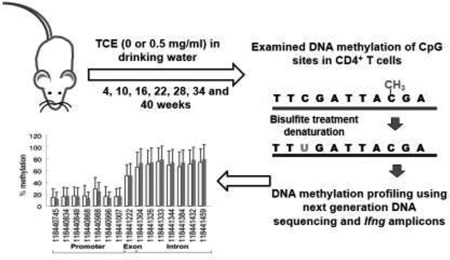

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Mouse models which combine genetic susceptibility and an environmental stressor can be utilized to study toxicant-induced autoimmune disease etiology. Using such a model we have shown that chronic exposure to the industrial solvent and common water pollutant trichloroethylene (TCE) generates a slow-developing autoimmune disease that closely resembles human autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).(1,2) Several autoimmune diseases and hypersensitivity disorders have been linked to human TCE exposure.(3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14) In our mouse model TCE appeared to predominantly impact CD4+ T cells, resulting in increased percentages of effector/memory CD4+ T cells and increased production of IFN-γ by CD4+ T cells. However, the effect of TCE on IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells was inconsistently detected depending upon the length of the TCE exposure.(1,15)

Autoimmune disease development is a lengthy process with both linear and non-linear components. For example, human autoimmune pancreatitis appears to involve a biphasic mechanism in which the early stage involves release of IFN-γ, while the chronic stage is instead mediated by Th2-like cytokines.(16) Similar to many human autoimmune diseases, studies in rodent models have shown that levels of specific cytokines such as IFN-γ can wax and wane during the different stages (e.g. onset, peak and regression) of disease development.(17) Expression kinetics ranging from bell-shaped, biphasic, and linear have been noted for different cytokines and chemokines in specific tissues in a model of adjuvant arthritis in rats.(18) A biphasic cytokine response in which an early increase in IFN-γ in the blood is followed by an increase in IL-17 and TNF-α was found in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis.(19) Similarly, IFN-γ was shown to promote the early induction phase of murine collagen-induced arthritis, but to suppress later stages of the arthritic process.(20)

Generation of IFN-γ by CD4+ T cells is regulated at several levels, including differential activation of transcription factors such as STAT4 and STAT6.(21) Expression of Ifng has also been shown to be under epigenetic control.(22) Unlike the promoters of Il2 and Il4, the Ifng promoter is already hypomethylated in naïve murine CD4+ T cells and remains so when naïve CD4+ T cells differentiate into IFN-γ-secreting Th1 cells.(23) However, during differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells to Th2 cells silencing of Ifng expression is achieved by repressive DNA methylation on different CpG sites in the promoter.(21) Regulation is somewhat different in human CD4+ T cells in which methylation of the IFNG promoter in naïve cells is in the mid/high range, and requires demethylation to permit expression of IFNG by effector/memory CD4+ T cells. Even though the IFNG promoter in human naïve T cells is not hypomethylated, it can undergo increased methylation associated with gene silencing following exposure to xenobiotics, as demonstrated by CD4+ T cells from patients with diisocyanate asthma (24), in the cord white blood cells children of mothers exposed to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (25), and in the T cells of children exposed to secondhand smoke.(26) These studies point out the potential impact of xenobiotics on Ifng methylation, and therefore Ifng expression.

We have previously reported that chronic TCE exposure can alter DNA methylation; CD4+ T cells from mice exposed to TCE for 17 weeks showed increased expression of Iap (intracisternal A particle) retrotransposons and decreased global DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells.(15) The time-dependent effects of TCE on gene-specific DNA methylation was not evaluated. Since directional changes in global DNA methylation are often quite different from what occurs at the level of gene-specific CpG regions, the current study was designed to examine the impact of chronic adult TCE exposure on methylation of CpG sites in the Ifng promoter and exon/intron. In view of the seemingly non-linear IFN-γ production profile by CD4+ T cells in our mouse models, this examination encompassed a 40 week exposure to TCE.

Lastly, since DNA methylation patterns can be cell type specific both naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells isolated from MRL+/+ mice every 6 weeks during were assessed. The evaluation revealed time-dependent subset-specific TCE-induced alterations in DNA methylation of CpG sites flanking the Ifng transcription start site, and help explain the non-monotonic effect of TCE on CD4+ T cell IFN-γ production. This evaluation is also the first to examine the impact of a toxicant on gene-specific epigenetic drift.

Materials and Methods

Mouse treatment

Eight week-old female MRL+/+ mice (Jackson Laboratories; Bar Harbor, ME) were exposed to TCE as previously described.(15) The mice (8–9 mice/treatment group/time point) received 0 or 0.5 mg/ml TCE in their drinking water for 4, 10, 16, 22, 28, 34 or 40 weeks. Mice received drinking water and food (Harlan 7027) ad libitum. TCE exposure from water consumption averaged 40–50 mg/kg/day, in comparison to the Permissible Exposure Limit [established by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)] for TCE of approximately 76 mg/kg/day. All studies were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

CD4+ T cells

Mice were sacrificed at different time points, and splenic CD62Llo and CD62Lhi CD4+ T cell populations were isolated as described.(27) The resulting CD62Lhi CD4+ T cells (naïve CD4+) or CD62Llo CD4+ T cells (effector/memory CD4+ T cells) were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 antibody and anti-CD28 antibody for 20 hours.(28) The resulting culture supernatants were collected and evaluated for IFN-γ by ELISA, and the activated CD4+ T cells themselves were frozen in RLT (Qiagen) for subsequent examination of DNA methylation. To ensure sufficient cell numbers for the analyses each sample of CD4+ T cells used in the study originated as an equal number of pooled spleen cells from 2 – 3 mice resulting in 4 samples per time point within each treatment group.

DNA methylation

Targeted bisulfite next-generation sequencing (NGS) was performed at the Molecular Cytogenetics and Epigenetics facility of Columbia University. Amplicons were generated on a Fluidigm Access Array and sequenced using an Illumina MiSeq platform. Sequence alignment to chromosomal locations (mouse genome build mm10) and DNA methylation levels were determined using Bismark (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/bismark/).(29) The degree of methylation is expressed as the percentage of total cytosines methylated at individual CpG sites. For most CpG sites, hundreds of reads per sample were used for each percentage methylation determination. In all cases, at least 10 reads/CpG site/sample were used.

qRT-PCR

Fluorescence-based quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was conducted using RNA isolated from naïve or effector/memory CD4+ T cells as described.(2) Fold differences (log2) in expression were determined using expression levels of resting (unactivated) CD4+ T cells of the appropriate subset of control mice as the control (1×) expression level.

Gene Arrays

This assessment was conducted by the Genomics Core at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. All RNA samples extracted from CD4+ T cells had RIN (RNA integrity number) values of 8.0 or above. Total RNA (500 ng) was converted to cDNA, amplified and biotinylated by use of the Ambion Illumina TotalPrep™-96RNA Amplification Kit (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) . Gene expression profiling was performed using the Expression BeadChip System from Illumina (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw data were log2 transformed and normalized to the median intensity signal of 47,231 genes on the array. After normalization and filtering of low intensity spots, 2-sample Student’s t-tests were performed and these data were plotted against fold-change measurements. Statistical significance was set at false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis software (Redwood City, CA) was used for network identification

Statistics

The data are presented as means ± standard deviations. Most assays were conducted using naïve or effector/memory CD4+ T cells isolated from equal numbers of pooled spleen cells from 2–3 mice resulting in 4 samples/treatment group/time point. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p< 0.05. Differences between experimental groups were tested first with analysis of variance (ANOVA), and where the F test was significant, subsequent pairwise contrasts were tested using a two-sample t-test. CD4+ T cell concentration and gene expression values were right-skewed, and therefore these data were log-transformed for statistical analyses. Adjusting for multiple comparisons, p-values from pairwise comparisons that were smaller than the Bonferroni-adjusted significance level indicated statistical significance.

Results

TCE alters CD4+ T cell gene expression

A microarray approach was used to obtain a more comprehensive assessment of TCE-induced alterations in CD4+ T cell gene expression. This analysis used effector/memory (CD62Llo) CD4+ T cells collected from mice exposed to TCE at the 22 week time point. This time point was selected because it was temporally mid-range, when TCE-induced alterations in effector/memory CD4+ T cells are evident. Gene expression was examined 20 hours after activation of the CD4+ T cells in vitro. At a cutoff of FDR<0.05 and a fold-change >1.25, the expression of over 400 genes was found to be significantly altered in the activated effector/memory CD4+ T cells of mice exposed to TCE compared to similarly activated effector/memory CD4+ T cells from control mice. Approximately 75% of the gene changes observed represented decreased expression in the TCE-exposed mice. Altered expression of immune-associated genes in the effector/memory CD4+ T cells after 22 weeks of TCE exposure is listed in Table 1. A network evaluation suggested that gene expression increases induced after 22 weeks of TCE exposure centered on Ifng (data not shown).

Table 1.

Immune gene expression altered in effector/memory CD4+ T cells from mice exposed to TCE for 22 weeks compared to controls

| Genebank | Gene symbol |

Gene name |

|---|---|---|

| Increased gene expression | ||

| Cytokines/Chemokines | ||

| NM_007720.2 | Ccr8 | Chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 8 |

| NM_009969.4 | Csf2 | Colony stimulating factor 2 (granulocyte-macrophage) |

| NM_007913.5 | Egr1 | Early growth response 1 transcription factor |

| NM_008337.1 | Ifng | Interferon gamma |

| NM_008366.2 | Il2 | Interleukin 2 |

| NM_010556.4 | Il3 | Interleukin-3 |

| NM_010558.1 | Il5 | Interleukin-5 |

| NM_001039537.1 | Lif | Leukemia inhibitory factor |

| NM_010735.1 | Lta | Lymphotoxin A |

| NM_013693.2 | Tnf | Tumor necrosis factor |

| NM_011612.2 | Tnfrsf9 | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 9 |

| NM_011613.3 | Tnfsf11 | Tumor necrosis factor (ligand) superfamily, member 11 |

| NM_009424.2 | Traf6 | Tnf receptor-associated factor 6 |

| Decreased gene expression | ||

| Cytokines/Chemokines | ||

| NM_008332.2 | Ifit2 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 2 |

| NM_010501.2 | Ifit3 | Interferon-induced protein with tetratricopeptide repeats 3 |

| NM_010511.2 | Ifngr1 | Interferon gamma receptor 1 |

| NM_008390.1 | Irf1 | Interferon regulatory factor 1 |

| NM_016850.2 | Ifr7 | Interferon regulatory factor 7 |

| NM_008394.2 | Irf9 | Interferon regulatory factor 9 |

| Apoptosis | ||

| NM_026976.2 | Faim3 | Fas apoptotic inhibitory molecule 3 |

| NM_011050.3 | Pdcd4 | Programmed cell death 4 |

| Signal transduction | ||

| NM_019963.1 | Stat2 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 |

| Integrin | ||

| NM_010581.3 | Cd47 | Integrin-associated signal transducer |

| NM_007799.2 | Cd180 | CD180 antigen |

| NM_010545.3 | Cd74 | Major histocompatibility complex, class II antigen-associated |

| NM_010741.2 | Ly6c1 | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus C1 |

| NM_010742.1 | Ly6d | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus D |

| NM_008529 | Ly6e | Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus E |

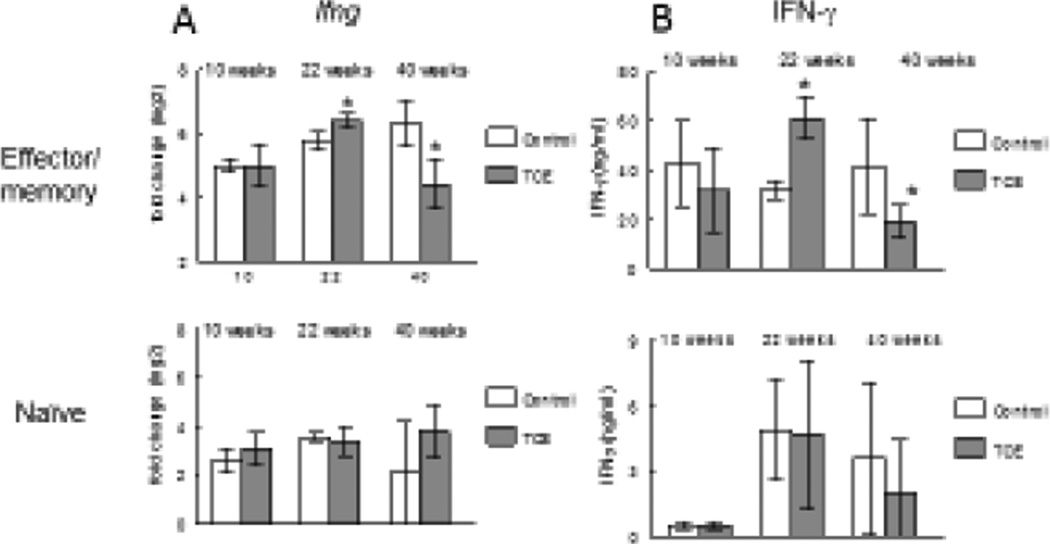

To confirm and extend the microarray results regarding Ifng, the effects of TCE on the expression of Ifng were examined by qRT-PCR at 10-, 22-, and 40-week time points in both naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells. Gene expression was examined 24 hours after activation of the CD4+ T cells in vitro, and compared to resting CD4+ T cells of the appropriate subset from control mice. In effector/memory CD4+ T cells from control mice the activation-induced expression of Ifng remained fairly constant over time (Figure 1A). In contrast, exposure to TCE caused a peak-and-valley pattern of Ifng expression in effector/memory CD4+ T cells with an increase at 22 weeks and a decrease at 40 weeks. This result recapitulated the 22-week TCE-induced increase in Ifng expression found in the array analysis. It also supported the apparent plasticity of the TCE effect on Ifng in the effector/memory CD4+ T cells. Unlike effector/memory CD4+ T cells naïve CD4+ T cells did not demonstrate TCE-induced changes in Ifng expression. In addition to gene expression, protein levels of IFN-γ secreted by the different subsets of CD4+ T cells at the 3 time points were evaluated. This result mirrored the qRT-PCR results, showing that effector/memory CD4+ T cells from TCE-treated mice produced more IFN-γ than controls at 22 weeks, and less IFN-γ than controls at 40 weeks (Figure 1B). Taken together, it appeared that exposure to TCE had non-monotonic effects on IFN-γ at both the gene and protein level. These effects were confined to effector/memory CD4+ T cells, and eventually resulted in a downregulation of the cytokine.

Figure 1. Chronic TCE exposure induced non-monotonic effects on IFN-γ.

Female MRL+/+ mice were exposed to TCE (0.05 mg/ml) for 4, 22 or 40 weeks. Effector/memory (CD62Llo) and naïve (CD62lhi) CD4+ T cells were isolated from the spleens and activated ex vivo. Both Ifng expression (A) and secreted IFN-γ (B) was measured. *Significantly different (p<0.05) compared to control values. At the 40 week time point, the number of CD62Llo effector/memory CD4+ T cells per mouse spleen was significantly different between control mice (5.6 ± 2.3 × 107) and TCE-treated mice (8.9 ± 2 × 107).

DNA methylation of CpG sites associated with cytokines in CD4+ T cells

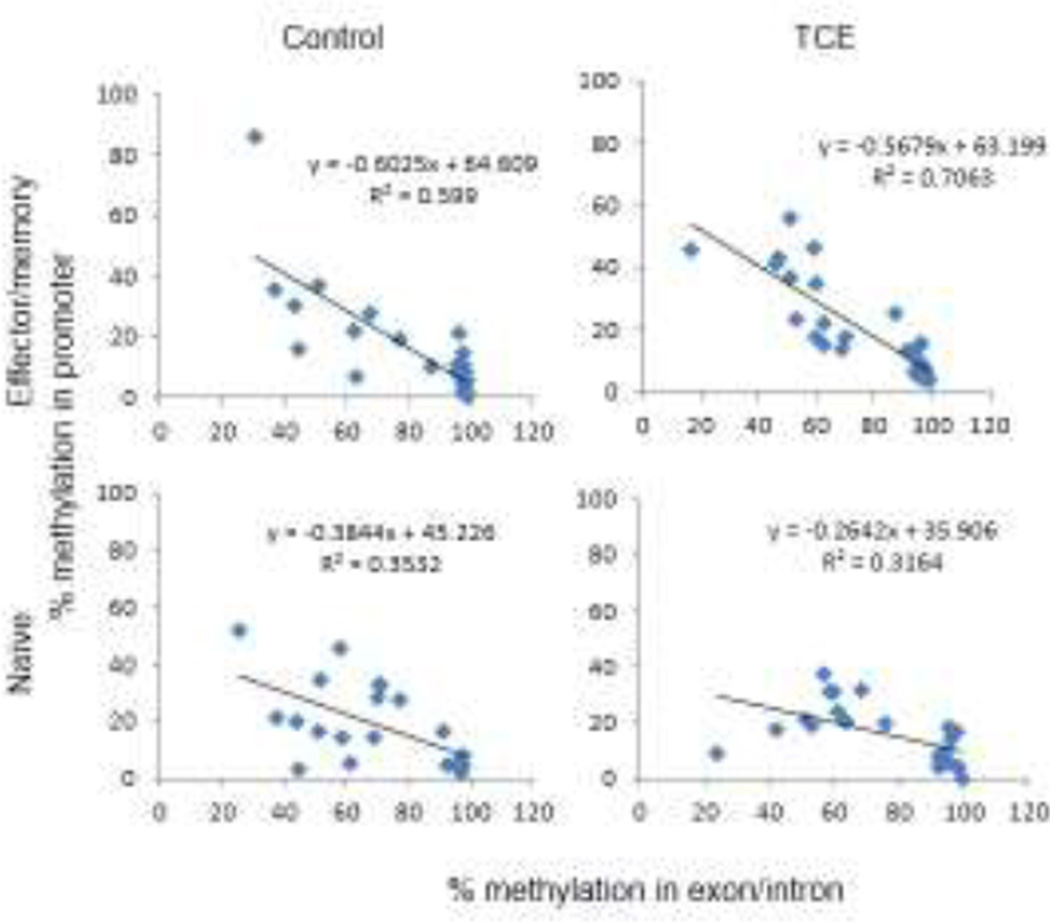

Targeted bisulfite NGS was used to test whether the decrease in Ifng expression in effector/memory CD4+ T cells after 40 weeks of TCE exposure was associated with specific changes in DNA methylation. Both naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells were evaluated at each of the seven time points. The analysis targeted the region of the Ifng promoter where methylation of individual CpGs has been shown to regulate gene expression(23). The CpG sites we examined are in an 800 bp region approximately centered on the transcription start site (TSS) and included seven CpG sites in the upstream (promoter) region and eight CpG sites in the downstream (exon and intron) region(27). CpG sites in the Ifng promoter displayed consistently low-to-medium (under 40%) levels of DNA methylation regardless of CD4+ T cell subset, mouse age, or TCE exposure. In contrast, CpG sites in the exon/intron uniformly demonstrated intermediate-to-high (over 60%) levels of DNA methylation. Interestingly, within individual samples, we observed an inverse correlation between the cumulative methylation of the CpG sites in the promoter and the cumulative methylation of the CpG sites in the exon/intron (Figure 2). Thus, when methylation was increased at the CpG sites in the promoter of a sample it was decreased at the CpG sites in the exon/intron of that sample, and vice versa. This correlation was most evident in the effector/memory CD4+ T cells from control (R2 = 0.599) and TCE-treated (R2=0.706) mice. A similar correlation, albeit less robust, was observed when comparing the CpG methylation in the promoter to the exon/intron region of Ifng in naïve CD4+ T cells. The interconnected methylation levels flanking the Ifng TSS suggested the presence of a mechanism to stabilize DNA methylation in this gene region.

Figure 2. Relationship of methylation of CpG sites in the promoter and exon/intron of Ifng.

Scatter plots show the correlation between the mean DNA methylation of CpG sites in the promoter in a single sample and the mean DNA methylation of the CpG sites in the exon/intron of the same sample. Data was collected from naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells across all time points, and each point represents a single sample.

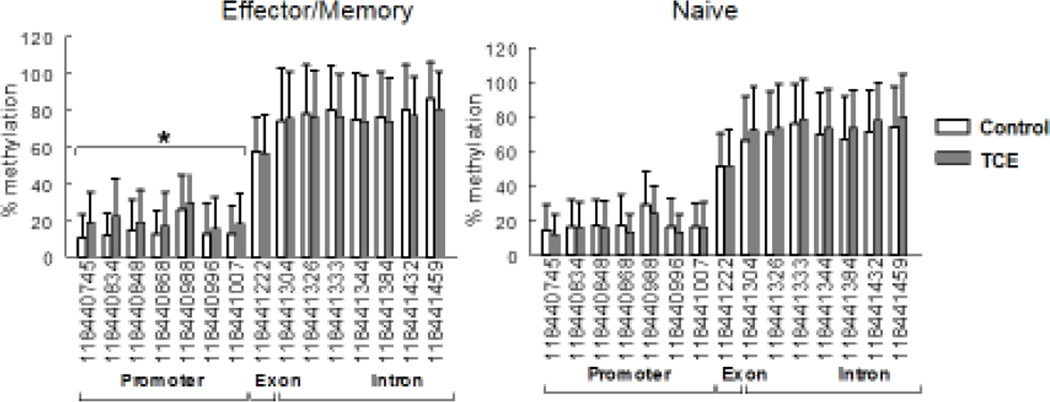

The effect of TCE exposure on the mean DNA methylation levels of the 15 individual CpG sites are illustrated in Figure 3. The results represent the average DNA methylation of individual CpG sites measured over all seven time points. When the CpG sites in the Ifng promoter were examined individually at specific time points, none of the TCE-induced changes in DNA methylation reached statistical significance. However, when examined cumulatively, the CpG sites in the Ifng promoter showed a significant increase in DNA methylation in effector/memory CD4+ T cells from TCE-treated mice. This cumulative TCE-induced increase in DNA methylation in the Ifng promoter was not found in naïve CD4+ T cells. There was no consistent cumulative effect of TCE on the methylation status of CpG sites in the exon/intron region of Ifng in either effector/memory or naïve CD4+ T cells. This finding showed that despite the tight control of DNA methylation in CpG sites flanking the Ifng TSS, TCE could alter that pattern in effector/memory, but not naïve CD4+ T cells.

Figure 3. Mean methylation of Ifng-associated CpG sites in both effector/memory and naïve CD4+ T cells.

DNA methylation at CpG sites in both the promoter and exon/intron region of Ifng in effector/memory and naïve CD4+ T cells from control or TCE-treated mice was determined. Shown is the mean methylation of the data collected at all 7 time points. The CpG sites are designated by chromosome position. *Significantly different (p<0.05) compared to control values.

Effects of TCE on epigenetic drift

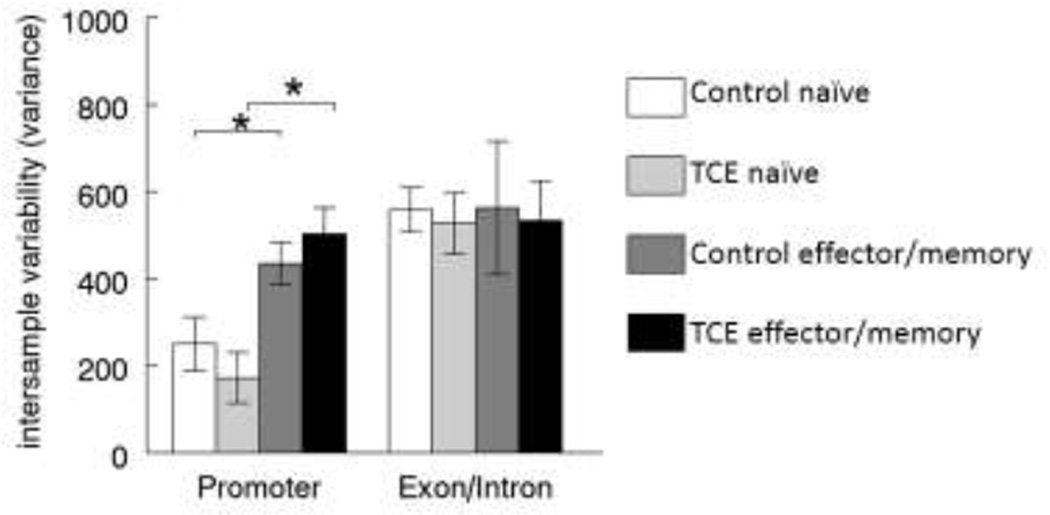

TCE has been shown to have subtle effects on interindividual variance in DNA methylation (epigenetic drift) in CD4+ T cells.(27) We extended that finding to examine epigenetic drift specifically associated with Ifng. Interesting, variance in the CpG sites in the Ifng promoter increased when CD4+ T cells differentiated from naïve to effector/memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 4). This was true in effector/memory CD4+ T cells from both control and TCE-treated mice. Variance in the DNA methylation of CpG sites in the exon/intron region of Ifng was not increased by differentiation from naïve to effector/memory CD4+ T cell status. Taken together these findings suggest that methylation of the Ifng promoter is unique in several ways, including the fact that differentiation from naïve to effector/memory CD4+ T cells results in an increase in the otherwise tightly controlled methylation variance, and that this variance may help make the effector/memory CD4+ T cells susceptible to TCE-induced changes in DNA methylation.

Figure 4. Alterations in methylation variance in CpG sites of Ifng promoter in effector/memory CD4+ T cells.

Methylation variance was measured across all time points for CpG sites in the promoter or exon/intron regions of Ifng in both naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells from control and TCE-treated mice. *Significantly different (p<0.05) compared to control values.

Discussion

Most studies of autoimmune disease, whether in humans or animal models, represent a snapshot of a limited number of events at a single time point. However, it is clear that longitudinal investigations are needed to generate the most accurate picture of the events that initiate and maintain disease development. Using a long-term multi-endpoint evaluation this study demonstrated a non-monotonic effect of TCE exposure on IFN-γ production by effector/memory CD4+ T cells. Other investigators have similarly shown temporal differences in IFN-γ expression and/or production over the course of autoimmune disease development. For example, it has been reported that EAE disease pathology was preceded by an increase in IFN-γ production by splenic T cells, followed by a decrease in splenic IFN-γ production.(30) Similarly, the kinetics of IFN-γ production by lymph node cells in experimental autoimmune arthritis was shown to be a critical part of disease pathology, and to determine whether treatment with exogenous IFN-γ at different times in disease development was protective.(31) However, since these studies measured IFN-γ using whole splenic T cells, or whole lymph node populations it is difficult to known how they reflect activity in individual CD4+ T cell subsets. Our study shows that even within the effector/memory CD4+ T cell subset, IFN-γ production was not linear.

As a pleotropic regulator it is not surprising that IFN-γ levels can change over the course of disease development to reflect both pro- and anti-inflammatory effects. IFN-γ is dichotomous in the regulation of distinct chemokine genes in the livers of mice with fulminant autoimmune hepatitis.(32) Similarly, although known primarily as an autoimmune-promoting cytokine IFN-γ can inhibit the development of experimental autoimmune uveitis (33), experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (34), and autoimmune arthritis.(31) Especially relevant to our study in MRL+/+ mice was the finding that exogenous IFN-γ has dichotomic effects on the development of spontaneous lupus in closely-related MRL lpr/lpr mice, both inhibiting and worsening disease progression depending on the stage of disease process.(35)

It has been reported that DNA methylation in a relatively small region of the Ifng promoter (that includes the −53, −205 and −297 CpG sites) controls promoter-driven Ifng expression during CD4+ T cell differentiation.(36,23) This region of the Ifng promoter proximal to the TSS is hypomethylated in naïve and effector/memory murine CD4+ T cells, while downstream regions proximal to the TSS are hypermethylated.(22) CD4+ T cells skewed toward a Th1 phenotype retain their relatively hypomethylated promoter sites (10 to 19% 5MC in three promoter sites), while the same sites demonstrated 30 to 56% 5MC in Th2 polarized cells.(23) Generally consistent with this methylation pattern, Th1 cells generated IFN-γ protein at 50 times the level of the Th2 polarized cells. In addition to the cytokines secreted during Th2 cell differentiation, certain environmental events such as adult exposure to diesel exhaust or developmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons can alter epigenetic marks in the Ifng promoter.(37,38,25) Low to moderate levels of methylation on the Ifng promoter such as we report here following TCE exposure may allow the gene to remain “poised” for varying levels of transcription. However, it appears that long-term exposure to TCE can increase the variance of that methylation, and eventually silence that transcription via increased DNA methylation. Effector/memory CD4+ T cells isolated after a 40-week TCE exposure demonstrated lower levels of both Ifng gene expression and IFN-γ protein secretion when compared to effector/memory CD4+ T cells from control mice. Thus, although in general effector/memory CD4+ T cells express more Ifng than naïve CD4+ T cells, on a per cell basis long-term exposure to TCE inhibited Ifng expression in the effector/memory CD4+ T cell subset. It appears that TCE-induced expansion of effector/memory CD4+ T cells is distinct from TCE-induced increased cytokine production by CD4+ T cells. The cumulative effects of long-term TCE exposure on effector/memory CD4+ T cells, combined with the differential IFN-γ production by naïve and effector/memory CD4+ T cells, may account for the seemingly non-linear IFN-γ profile measured in unseparated populations of CD4+ T cells at different times during TCE exposure.

Our previous study showed that CpG sites for most genes displayed either low 0–20% methylation or high 80–100% methylation.(27) This pattern was very stable over time, and variation in the DNA methylation of a particular site was largely due to stochastic effects related to mean methylation of the site. Thus, variance for sites that averaged 0–20% or 80–100% methylation was uniformly low, while variance was highest for CpG sites where the average methylation was intermediate. This mathematical phenomenon has been described by others.(39) In comparison to the CpG sites for the other genes examined, the CpG sites in the Ifng promoter did not conform well to the model in which methylation variability was linked to mean methylation levels (27). This suggested that compared to several other genes methylation of CpGs in the Ifng promoter was less tightly controlled, and more susceptibility to changes induced by external factors such as exposure to TCE.

It should be noted that one limitation of this study was the need to pool spleen cells from 2–3 mice in order to obtain sufficient numbers of both effector/memory and naïve CD4+ T cells. Although this eliminated possible confounding effects that might result from different percentages of the two subsets in a sample, it may have decreased the ability to detect subtle consistent changes in DNA methylation of individual CpG sites. It should also be noted that we do not know whether the decrease in IFN-γ observed in memory CD4+ T cells from mice exposed to TCE for 40 weeks was an important part of disease progression or a compensatory mechanism designed to protect against the pro-inflammatory effects of the cytokine.

Highlights.

Chronic TCE decreased IFN-γ production by effector/memory CD4+ T cells

TCE increased DNA methylation of Ifng promoter in effector/memory CD4+ T cells

Ifng promoter of effector/memory CD4+ T cells susceptible to epigenetic drift

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Rachel Lee and Dustyn Barnette for excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Arkansas Biosciences Institute, the National Institutes of Health (R01ES017286, R01ES021484), the Organic Compounds Property Contamination class action settlement (CV 1992-002603), and the UAMS Translational Research Institute (National Institutes of Health UL1RR029884).

Abbreviations

- TCE

trichloroethylene

- TSS

transcription start site

- AIH

autoimmune hepatitis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sarah J. Blossom, Email: blossomsarah@uams.edu.

Stephen W. Erickson, Email: serickson@rti.org.

Brannon Broadfoot, Email: bbroadfoot@uams.edu.

Kirk West, Email: kwest@uams.edu.

Shasha Bai, Email: sbai@uams.edu.

Jingyun Li, Email: JLi@uams.edu.

Craig A. Cooney, Email: cooneycraiga@gmail.com.

Reference List

- 1.Griffin JM, Gilbert KM, Lamps LW, Pumford NR. CD4+ T cell activation and induction of autoimmune hepatitis following trichloroethylene treatment in MRL+/+ mice. Toxicol.Sci. 2000;57:345–352. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/57.2.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilbert KM, Przybyla B, Pumford NR, et al. Delineating liver events in trichloroethylene-induced autoimmune hepatitis. Chem.Res Toxicol. 2009;22(4):626–632. doi: 10.1021/tx800409r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byers VS, Levin AS, Ozonoff DM, Baldwin RW. Association between clinical symptoms and lymphocyte abnormalities in a population with chronic domestic exposure to industrial solvent-contaminated domestic water supply and a high incidence of leukemia. Cancer Immunol.Immunother. 1988;27:77–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00205762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanez Diaz S, Moran M, Unamuno P, Armijo M. Silica and trichloroethylene-induced progressive systemic sclerosis. Dermatol. 1992;184:98–102. doi: 10.1159/000247513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen BL, Isager H. A scleroderma-resembling disease-exposure to trichloroethylene and trichloroethane, is there a causal connection? Ugeskr.Laeger. 1988;150:805–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saihan EM, Burton JL, Heaton KW. A new syndrome with pigmentation, scleroderma, gynaecomastia, Raynaud's phenomenon and peripheral neuropathy. B.J.Dermatol. 1978;99:437–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb06184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flindt-Hansen H, Isager H. Scleroderma after occupational exposure to trichloroethylene and trichlorethane. Toxicol.Lett. 1987;95:173–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czirjak L, Pocs E, Szegedi G. Localized scleroderma after exposure to organic solvents. Dermatology. 1994;189(4):399–401. doi: 10.1159/000246888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lockey JE, Kelly CR, Cannon GW, Colby TV, Aldrich V, Livingston GK. Progressive systemic sclerosis associated with exposure to trichloroethylene. J.Occup.Med. 1997;29:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubrow R, Gute DM. Cause-specific mortality among Rhode Island jewelry workers. Am.J Ind.Med. 1987;12(5):579–593. doi: 10.1002/ajim.4700120511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gist GL, Burg JR. Trichloroethylene--a review of the literature from a health effects perspective. Toxicol.Ind.Health. 1995;11(3):253–307. doi: 10.1177/074823379501100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond GR. Hepatitis, rash and eosinophilia following trichloroethylene exposure: a case report and speculation on mechanistic similarity to halothane induced hepatitis. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1996;34(4):461–466. doi: 10.3109/15563659609013819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu X, Yang R, Wu N, et al. Severe hypersensitivity dermatitis and liver dysfunction induced by occupational exposure to trichloroethylene. Ind.Health. 2009;47(2):107–112. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.47.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kobayashi R, Ikemoto T, Seo M, et al. Enhancement of immediate allergic reactions by trichloroethylene ingestion via drinking water in mice. J Toxicol Sci. 2010;35(5):699–707. doi: 10.2131/jts.35.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilbert KM, Nelson AR, Cooney CA, Reisfeld B, Blossom SJ. Epigenetic alterations may regulate temporary reversal of CD4(+) T cell activation caused by trichloroethylene exposure. Toxicol Sci. 2012;127(1):169–178. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okazaki K, Uchida K, Fukui T. Recent advances in autoimmune pancreatitis: concept, diagnosis, and pathogenesis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43(6):409–418. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Astry B, Venkatesha SH, Moudgil KD. Temporal cytokine expression and the target organ attributes unravel novel aspects of autoimmune arthritis. Indian J Med Res. 2013;138(5):717–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nanjundaiah SM, Stains JP, Moudgil KD. Kinetics and interplay of mediators of inflammation-induced bone damage in the course of adjuvant arthritis. Int J Immunopathol.Pharmacol. 2013;26(1):37–48. doi: 10.1177/039463201302600104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lunin SM, Glushkova OV, Khrenov MO, et al. Thymic peptides restrain the inflammatory response in mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Immunobiology. 2013;218(3):402–407. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boissier MC, Chiocchia G, Bessis N, et al. Biphasic effect of interferon-gamma in murine collagen-induced arthritis. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25(5):1184–1190. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams CL, Schilling MM, Cho SH, et al. STAT4 and T-bet are required for the plasticity of IFN-gamma expression across Th2 ontogeny and influence changes in Ifng promoter DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2013;191(2):678–687. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas RM, Saouaf SJ, Wells AD. Superantigen-induced CD4+ T cell tolerance is associated with DNA methylation and histone hypo-acetylation at cytokine gene loci. Genes Immun. 2007;8(7):613–618. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Winders BR, Schwartz RH, Bruniquel D. A distinct region of the murine IFN-gamma promoter is hypomethylated from early T cell development through mature naive and Th1 cell differentiation, but is hypermethylated in Th2 cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(12):7377–7384. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ouyang B, Bernstein DI, Lummus ZL, et al. Interferon-gamma promoter is hypermethylated in blood DNA from workers with confirmed diisocyanate asthma. Toxicol Sci. 2013;133(2):218–224. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang WY, Levin L, Talaska G, et al. Maternal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and 5'-CpG methylation of interferon-gamma in cord white blood cells. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(8):1195–1200. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kohli A, Garcia MA, Miller RL, et al. Secondhand smoke in combination with ambient air pollution exposure is associated with increasedx CpG methylation and decreased expression of IFN-gamma in T effector cells and Foxp3 in T regulatory cells in children. Clin Epigenetics. 2012;4(1):17–14. doi: 10.1186/1868-7083-4-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilbert KM, Blossom SJ, Erickson SW, et al. Chronic exposure to water pollutant trichloroethylene increased epigenetic drift in CD4+ T cells. Epigenomics. 2016 doi: 10.2217/epi-2015-0018. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert KM, Pumford NR, Blossom SJ. Environmental Contaminant Trichloroethylene Promotes Autoimmune Disease and Inhibits T-cell Apoptosis in MRL+/+ Mice. J Immunotox. 2006;3:263–267. doi: 10.1080/15476910601023578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger F, Andrews SR. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(11):1571–1572. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofstetter HH, Forsthuber TG. Kinetics of IL-17- and interferon-gamma-producing PLPp-specific CD4 T cells in EAE induced by coinjection of PLPp/IFA with pertussis toxin in SJL mice. Neurosci Lett. 2010;476(3):150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajaiah R, Puttabyatappa M, Polumuri SK, Moudgil KD. Interleukin-27 and interferon-gamma are involved in regulation of autoimmune arthritis. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(4):2817–2825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.187013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milks MW, Cripps JG, Lin H, et al. The role of Ifng in alterations in liver gene expression in a mouse model of fulminant autoimmune hepatitis. Liver Int. 2009;29(9):1307–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02028.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tarrant TK, Silver PB, Wahlsten JL, et al. Interleukin 12 protects from a T helper type 1-mediated autoimmune disease, experimental autoimmune uveitis, through a mechanism involving interferon gamma, nitric oxide, and apoptosis. J Exp Med. 1999;189(2):219–230. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wildbaum G, Zohar Y, Karin N. Antigen-specific CD25- Foxp3- IFN-gamma(high) CD4+ T cells restrain the development of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by suppressing Th17. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(6):2764–2775. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicoletti F, Di MR, Zaccone P, et al. Dichotomic effects of IFN-gamma on the development of systemic lupus erythematosus-like syndrome in MRL-lpr / lpr mice. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30(2):438–447. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200002)30:2<438::AID-IMMU438>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones B, Chen J. Inhibition of IFN-gamma transcription by site-specific methylation during T helper cell development. EMBO J. 2006;25(11):2443–2452. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strickland FM, Li Y, Johnson K, Sun Z, Richardson BC. CD4 T cells epigenetically modified by oxidative stress cause lupus-like autoimmunity in mice. J Autoimmun. 2015;(15):10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu J, Ballaney M, Al-alem U, et al. Combined inhaled diesel exhaust particles and allergen exposure alter methylation of T helper genes and IgE production in vivo. Toxicol Sci. 2008;102(1):76–81. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacoby M, Gohrbandt S, Clausse V, Brons NH, Muller CP. Interindividual variability and co-regulation of DNA methylation differ among blood cell populations. Epigenetics. 2012;7(12):1421–1434. doi: 10.4161/epi.22845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]