Abstract

Purpose

Patient navigation is an intervention approach that improves cancer outcomes by reducing barriers and facilitating timely access to cancer care. Little is known about the benefits of patient navigation during breast cancer treatment and survivorship. This systematic review evaluates the efficacy of patient navigation in improving treatment and survivorship outcomes in women with breast cancer.

Methods

The review included experimental and quasi-experimental studies of patient navigation programs that target breast cancer treatment and breast cancer survivorship. Articles were systematically obtained through electronic database searches of PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library. The Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool was used to evaluate the methodologic quality of individual studies.

Results

Thirteen studies met the inclusion criteria. Most were of moderate to high quality. Outcomes targeted included timeliness of treatment initiation, adherence to cancer treatment, and adherence to post-treatment surveillance mammography. Heterogeneity of outcome assessments precluded a meta-analysis. Overall, results demonstrated that patient navigation increases surveillance mammography rates, but only minimal evidence was found with regard to its effectiveness in improving breast cancer treatment outcomes.

Conclusion

This study is the most comprehensive systematic review of patient navigation research focused on improving breast cancer treatment and survivorship. Minimal research has indicated that patient navigation may be effective for post-treatment surveillance; however, more studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions about the efficacy of patient navigation during and after cancer treatment.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advancements in cancer screening, early detection, and cancer treatments, significant racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in cancer outcomes still remain.1,2 These disparities are partly due to unequal access to timely, high-quality cancer care among racially diverse and lower socioeconomic status populations.3-5 Delays in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment are associated with larger tumors, late-stage diagnosis, lower cure rates, disease progression, poorer prognosis, and shorter survival.6,7

Patient navigation is a potential strategy to reduce cancer-related disparities and improve outcomes by eliminating barriers to obtaining quality cancer care. Patient navigation refers to the individualized assistance provided to patients through the cancer care continuum to navigate the complex health care system.8 As an intervention model, patient navigation generally provides assistance to individual patients for a defined episode of cancer-related care, targets a defined set of health services to complete a specific cancer care goal, has a defined end point in which service delivery is complete, focuses on identifying and resolving barriers to receiving care, and aims to reduce delays in accessing services throughout the continuum of cancer care.9 Cancer-related patient navigation programs vary widely in terms of the personnel and services provided.9,10 Patient navigators may be health care professionals (eg, nurses, social workers) or lay/community health workers (eg, peer supporters, cancer survivors) with various educational backgrounds and training.10 Depending on the needs of patients, barriers identified, and targeted cancer care goals, navigators provide a wide range of support, including emotional, logistical/practical, and informational.11

Previous reviews of patient navigation in cancer care have suggested that patient navigation is effective in improving cancer screening rates, adherence to follow-up care after abnormal results, and timeliness of diagnostic resolution, whereas evidence of patient navigation reducing late-stage cancer diagnosis or improving cancer treatment outcomes is limited or inconclusive.9,10,12 These reviews, however, lack methodologic rigor in that they did not involve a comprehensive search of the literature. They used only a single biomedical database (PubMed)9,10,12 or an additional similar database (Ovid)12 to locate studies, which restricted the identification of relevant articles from other databases. In addition, these reviews did not examine the methodologic quality of included studies. Despite the proliferation of research in patient navigation, efficacy studies of patient navigation to improve breast cancer care have not been reviewed since 2011,10 and no systematic review has evaluated the use of patient navigation during breast cancer treatment and survivorship. We therefore conducted a comprehensive systematic review of intervention studies that assessed the efficacy of patient navigation in improving outcomes related to breast cancer treatment and survivorship. The purpose of this systematic review was to identify patient navigation programs that target breast cancer treatment and survivorship, evaluate the efficacy of patient navigation on cancer treatment and survivorship outcomes compared with usual care in women with breast cancer, and critically examine and synthesize the cumulative evidence on the effectiveness of patient navigation in improving breast cancer treatment and survivorship care.

METHODS

Search Strategy

The search was limited to articles that were published after 1990, which was the year the first patient navigation program was implemented in the United States.13 PubMed/MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Web of Science, CINAHL, and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched from 1990 to March 2015 by using prespecified Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords to identify patient navigation interventions to improve breast cancer treatment and survivorship outcomes. Combinations of terms associated with breast cancer, patient navigation, cancer treatment, and cancer survivorship were used. The final search strategy used for PubMed/MEDLINE (Table 1) was adapted for each electronic database. Reference lists and keyword searches from eligible articles were also reviewed to identify additional publications.

Table 1.

PubMed/MEDLINE Search Strategy

| 1 | “Breast neoplasms” [MeSH] OR “breast neoplasm” OR “breast cancer” OR (breast cancer) |

| 2 | “Patient navigation” [MeSH] OR “patient navigation” OR navigation OR navigator OR (patient navigat*) OR (cancer navigat*) OR (nurse navigat*) OR (clinical navigat*) OR (client navigat*) OR (system navigat*) OR (professional navigat*) |

| 3 | “Breast neoplasms/therapy” [MeSH] OR “breast neoplasms/drug therapy” [MeSH] OR “breast neoplasms/radiotherapy” [MeSH] OR “breast neoplasms/surgery” [MeSH] OR “mastectomy” [MeSH] OR “estrogen receptor modulators” [MeSH] OR “combined modality therapy” [MeSH] OR “antineoplastic agents” [MeSH] OR (cancer treatment) OR (cancer therapy) OR chemotherapy OR “radiotherapy” [MeSH] OR “survivors” [MeSH] OR surviv* OR surveillance OR “mammography” [MeSH] OR mammogram OR “post treatment” OR “follow-up care” OR “follow-up treatment” OR “follow-up therapy” OR “long-term care” OR “long-term treatment” OR “long-term therapy” OR “survivorship care” |

| 4 | 1 AND 2 AND 3 |

Abbreviation: MeSH, Medical Subject Headings.

Study Selection

Citations from all search results were downloaded and merged by using a reference management software package (EndNote X7.3.1; Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA). One author (S.H.B.) screened study titles and abstracts for potential inclusion and then reviewed full-text articles, including reference lists, to determine their eligibility. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were written in English, conducted in the United States, evaluated a patient navigation intervention for patients with breast cancer during treatment and/or survivorship, and empirically examined treatment and/or survivorship outcomes. For the purpose of this review, patient navigation was defined as an intervention that reduces barriers to care and targets a particular cancer care goal. For the purpose of evaluating cancer care outcomes post-treatment, cancer survivorship was defined as the period that follows completion of primary cancer treatment up to end of life.14

Study designs eligible for inclusion were experimental or quasi-experimental studies (eg, randomized controlled trials [RCTs], nonrandomized trials) that included an intervention group that received patient navigation and a control group (eg, usual care) for comparison. Study participants were restricted to women with breast cancer who were prescribed to begin, were undergoing, or had completed medical treatment for breast cancer. Studies were limited to those conducted in the United States due to substantial differences in health care systems among countries, including other English-speaking countries (eg, Canada, United Kingdom). Studies without a comparison group or without quantitative analyses were also excluded. Studies were not excluded if patient navigation was combined with another intervention or if either intervention or comparison group included patients with another cancer type on the condition that analyses were conducted separately for patients with breast cancer. Review articles, published abstracts, conference proceedings, intervention manuals, and unpublished studies were excluded.

Data Extraction

A standardized spreadsheet was used to extract data on study setting and design, intervention characteristics (description of patient navigation intervention and/or navigator, intervention, and control group details), sample characteristics (sample size, age, race/ethnicity, primary language, and health insurance status), outcomes related to cancer treatment and survivorship, and quantitative assessment of targeted outcomes. Heterogeneity in outcome definitions and assessments did not permit the pooling of outcomes or a meta-analysis. The quality of evidence for each study was examined by using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies,15 which evaluates selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding of study participants and assessors, data collection methods, and withdrawals and dropouts. The strength of each component and global ratings ranged from weak to strong.

RESULTS

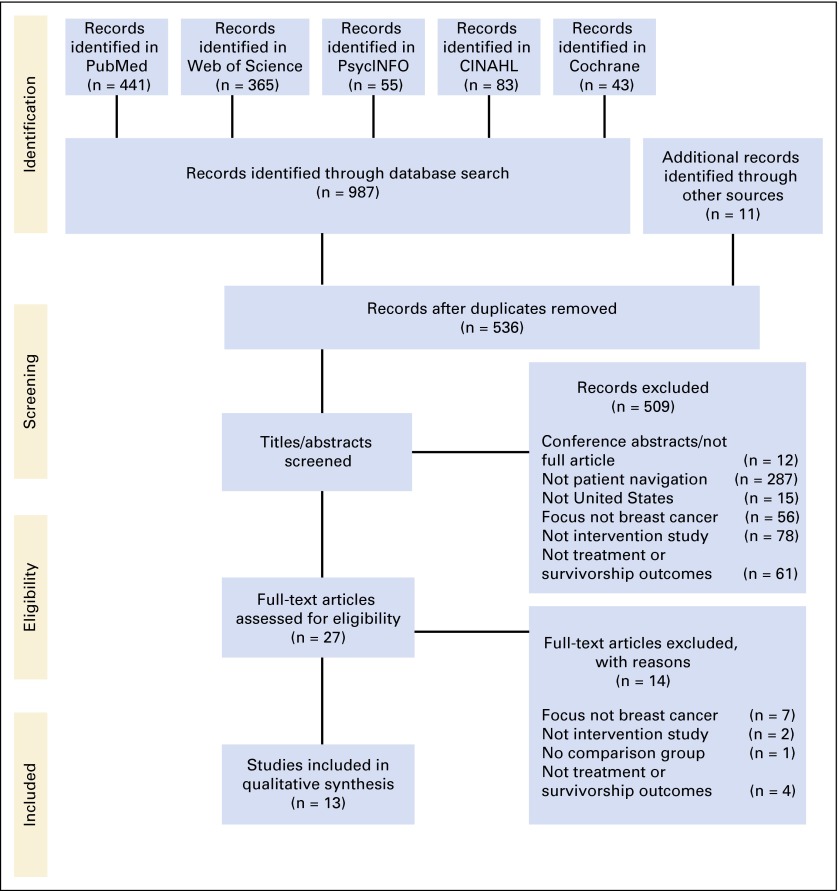

Figure 1 illustrates the study identification, screening, eligibility, and selection process. Nine hundred eighty-seven articles were identified through five database searches, and an additional 11 articles were identified from backward and forward searches. After removing duplicate publications, 536 titles and abstracts were screened for eligibility, and 509 articles were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria. After full-text review, 14 additional articles were excluded. Thirteen peer-reviewed studies were eligible for inclusion in the synthesis. Descriptions and results from the included studies are presented in Table 2.

Fig 1.

Diagram of study identification and selection process.

Table 2.

Summary of PNPs for Breast Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Care

| First Author | Study Design and Setting | Intervention | Sample Characteristics | Outcome Measures | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bickell16 |

|

|

|

Adjuvant treatment adherence rates for receipt of RT, CT, and HT | No statistically significant differences in adherence rates to adjuvant treatments between INT and CON were found. Both groups had high rates of RT (87% v 91%; P = .39), CT (93% v 86%; P = .42), and HT (92% v 93%; P = .80) |

| Chen17 |

|

PNs were bilingual (English, Spanish) and bicultural; were trained in medical interpretation, cultural competency, case management, and patient navigation; and provided community outreach, health education, psychosocial support, care coordination, and access to transportation and financial resources. |

|

|

|

| Dudley18 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Ell19 |

|

|

|

Initiation of cancer treatment within 30 days of diagnosis | No statistically significant difference was found in timeliness of treatment initiation between a subsample of INT (n = 64) and CON (n = 10) participants with breast cancer: 62% v 40% of INT v CON, respectively, initiated treatment within 30 days after diagnosis. |

| Ell20 |

|

PN was bilingual (English, Spanish) and provided telephone-based adherence risk assessment, health education, counseling, systems navigation, reminders, and referrals to community resources and MSW for psychosocial counseling. |

|

Initiation of cancer treatment within 30 days of diagnosis | Among a subsample of participants with breast cancer (INT, n = 5; CON, n = 10), 80% of INT and 60% of CON initiated treatment within 30 days after diagnosis. Statistical analyses were not performed due to small sample size. |

| Ell21 |

|

|

|

Adjuvant treatment adherence rates for completion of CT, RT, and HT | No statistically significant differences were found between groups for overall adjuvant treatment adherence rates: 90% v 88% of CON v INT, respectively, completed CT; 90% of patients in both groups completed RT. Overall adherence to HT was 59%, with no significant difference in rates between groups. |

| Haideri22 |

|

PNs provided patients with cell phones for appointment reminders; assistance with scheduling appointments and services; communication with health care providers; educational information; one-on-one emotional support; and financial, insurance, transportation, and child care assistance. |

|

|

|

| Ko23 |

|

|

|

Treatment adherence rates for receipt of HT and RT |

|

| Koh24 |

|

|

|

Initiation of cancer treatment (time from diagnostic biopsy to initiation of cancer treatment) | On average, INT initiated treatment in 26.2 days (SD, 9.15 days; 95% CI, 22.9 to 29.4 days), and CON initiated treatment in 30 days (SD, 11.79 days; 95% CI, 26.8 to 33.2 days). This shorter mean treatment interval from diagnostic biopsy was not statistically significant (t = 1.606; P = .112; d = .366). |

| Lobb25 |

|

Case managers were required to have current licensure or a national certificate in case management and a bachelor’s degree in health and human services or registered nurse license in Massachusetts. They provided support, education, coordinated care and patient-physician communication, assistance with appointment scheduling, transportation vouchers, and interpreter services and reduced health system barriers. |

|

Initiation of cancer treatment (time from abnormal mammogram to initiation of cancer treatment) | After the implementation of a case management program, time to treatment initiation from abnormal mammogram was reduced by 12 days, and an additional 3 days after the free treatment policy (57 v 45 v 42 days for CON v INT v FTP, respectively; P = .001). There was also a 39% reduction in the adjusted RR of treatment delay after implementing case management, but the decrease in risk was not statistically significant (RR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.33 to 1.14). |

| Raj26 |

|

PNs were culturally diverse, trained layworkers who provided patient navigation services. |

|

Treatment adherence rates for receipt of HT, CT, and RT | INT had comparable treatment adherence rates with NCCN patients: 95% of INT and 89% of NCCN received HT, 88% of INT and 87% of NCCN received CT, and 92% of INT and 95% of NCCN received RT. No statistically significant differences were found between rates. |

| Ramirez27 |

|

|

|

Initiation of cancer treatment within 30 or 60 days of diagnosis |

|

| Weber28 |

|

PN was a registered nurse; assisted patients in overcoming individual barriers to accessing cancer care; and provided health education, emotional support, and resources for physical and psychosocial support. |

|

|

|

Abbreviations: BCCEDP, Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program; CI, confidence interval; CON, control group; CT, chemotherapy; d, Cohen d effect size; FTP, free treatment policy; HR, hazard ratio; HT, hormone/hormonal (antiestrogen) therapy; INT, intervention group; MBA, Master of Business Administration; MSW, Master of Social Work; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NR, not reported; OR, odds ratio; PN, patient navigator; PNP, patient navigation program; PNRP, Patient Navigation Research Project; QE, quasi-experimental; RCT, randomized controlled trial; RR, risk ratio; RT, radiation therapy; SD, standard deviation.

Quality of Evidence

Table 3 summarizes the methodologic quality assessment used in this review. Nearly one half of the studies received moderate global quality ratings, as a result of weak ratings on withdrawals and dropouts (eg, did not report the number of participants who withdrew, dropped out, or completed the study),17,23,27 confounders (eg, control of confounders not described),18,25 and selection bias (eg, < 60% of eligible patients agreed to participate in study).16 Five studies received strong global ratings,20-22,24,28 and the remaining two studies received weak global ratings due to weak scores on study design,26 confounders,19 and withdrawals and dropouts.19 Overall, the quality rating for the 13 reviewed studies was moderate. Two of the included studies18,23 were part of the Patient Navigation Research Program (PNRP), a nine-site clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation.29 Although the studies assessed different outcomes, one combined data across sites,23 which may have included the other study’s sample.18 Furthermore, three studies19-21 were conducted by the same group of researchers, used the same or similar intervention (Screening Adherence Follow-Up program), and had similar study samples because participants may have been recruited from the same sites.

Table 3.

Component and Global Assessment of Study Quality by Using the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies

| First Author | Selection Bias | Study Design | Confounders | Blinding | Data Collection Method | Withdrawals and Dropouts | Global Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bickell16 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Chen17 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Dudley18 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Ell19 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Ell20 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Ell21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Haideri22 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Ko23 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Koh24 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Lobb25 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Raj26 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | NA | 3 |

| Ramirez27 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Weber28 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

NOTE. Effective Public Health Practice Project ratings: 1 = strong, 2 = moderate, 3 = weak.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Study Characteristics

Of the 13 studies, three were RCTs,16,20,21 one was a multicenter quasi-experimental study with various study designs that included RCTs and nonrandomized trials,23 one was a single-group study,26 four were prospective cohort studies,18,19,24,27 and four were retrospective cohort studies.17,22,25,28 The control groups comprised patients with breast cancer who received usual care or usual care plus written informational materials. In the single-group study, patients from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) centers served as the comparison group, and concordance data from NCCN institutions were used as a benchmark for navigated patients. Patient navigation programs were primarily health care institution–based safety net hospitals,18,21,22 public hospitals or medical centers,16,17,19,20,25,26 community-based health clinics,25,27 tertiary care centers,16,24 and academic institutions.23,28

Study Participant Characteristics

Study sample sizes ranged from 100 to 1,300 participants. Most study participants were middle-aged (50 years and older). Most patient navigation interventions were provided to specific racial/ethnic or underserved populations. Six studies17-21,27 evaluated the efficacy of patient navigation for low-income Hispanic/Latina women who were predominantly insured by government-sponsored health care programs (Medicaid, Medicare)18,21 or were mainly27 or exclusively17 uninsured. Spanish was the primary language among the majority of participants in three of these studies.17,21,27 Two studies were conducted among African American/black women22,28 who were primarily uninsured28 or received government-sponsored insurance.22 Three studies included ethnically diverse participants, including African American/black, Hispanic/Latina, and white women who mostly had private insurance.16,23,26 Two studies included predominantly white samples, one of which targeted low-income, uninsured women but did not provide sample characteristics on income or health insurance status,25 and the other included primarily participants who had private health insurance.24

Intervention Characteristics

All studies used patient navigation as the primary intervention mechanism and evaluated intervention outcomes in women with breast cancer. However, the patient navigation interventions were heterogeneous. Although most studies implemented a patient navigation program for patients with breast cancer,16-18,22-25,27,28 many included some variation of or combined patient navigation with another intervention component,19-21 such as psychosocial counseling. Two studies used culturally tailored patient navigation programs for Hispanic/Latina women with breast cancer.21,27 One study used a two-team approach that paired a patient navigator with a promotora and was on the basis of a care management model.18 Another study used a case management program.25

The personnel who provided navigation services varied among studies. Patient navigators were described as nurses,18,24,25,28 health care facilitators,22 outreach workers,16 case managers,25 social workers,18 a dental hygienist,18 peer counselors,19 trained community health workers,27 and trained layworkers.26 Patient navigators in five studies were bilingual in English and Spanish.17,19-21,27 Training of patient navigators also varied. Whereas four studies specified that navigators were trained in patient navigation,17 identification and resolution of barriers to care,16 care coordination for diagnostic evaluation and treatment,27 cultural competency,17,20 or case management and medical interpretation,17 details about the training (eg, length, delivery method, curriculum) and quality of training were limited or not reported. In three studies, navigators received training based on guidelines previously developed by the Institute for Health Promotion Research27 or navigation training programs through the Patient Navigation Research Program,18,23 which are described in greater detail elsewhere.30 In addition, three studies specified educational or professional requirements for patient navigators, which included at least a high school diploma or a college degree19,27 or current licensure/certificate in case management with a registered nurse license or bachelor’s degree in health and human services.25

Patient navigation programs also varied in the services provided, which were typically delivered through in-person meetings, telephone, or a combination of the two. Patient navigation services included health education about breast cancer, its treatments, and information about available services and resources16,17,19-23,27,28; emotional support16,17,19-23,27,28; assessment of barriers16,18,21; individualized action plans16,18,21; communication with the health care team22,25,27; coordination of care17,22,24,25; case management16,25; appointment scheduling and reminders16,19,20,22,25,27; accompaniment to appointments27; assistance with financial16,17,22 and health insurance22,27 issues; transportation services16,17,22,25,27; child care arrangements16,22,27; and translation services.25,27 Navigation was generally provided from diagnosis to treatment initiation,18 during the course of treatment,22 or through treatment completion.17,18,23,24

Efficacy of Patient Navigation

This article focuses exclusively on outcomes specific to breast cancer treatment and/or survivorship, so results on cancer care before treatment (eg, diagnostic resolution) or subsequent to survivorship (eg, end-of-life care) are not included. All 13 studies evaluated the effects of patient navigation on cancer treatment outcomes, and two evaluated post-treatment surveillance adherence, which was the only survivorship-related outcome identified.

Timeliness of care.

Seven studies focused on the efficacy of patient navigation in improving the timeliness of cancer treatment, operationalized as the time to primary cancer treatment initiation from the date of initial breast abnormality/abnormal result22,25 or diagnosis of breast cancer.18-20,24,27 Two studies that used a combined patient navigator and promotora intervention18 and a culturally tailored patient navigation program27 demonstrated that navigated patients were more likely to initiate treatment within 30 and 60 days from breast cancer diagnosis than non-navigated patients27 and had, on average, significantly shorter times (P < .05) from diagnosis to treatment by 1718 or 2627 days in predominantly low-income, uninsured, or publicly insured Hispanic/Latina patient populations. This significant difference was also more pronounced among Hispanic/Latina women than white women.18 Two other studies reported that a greater percentage of navigated patients initiated treatment within 30 days; however, these studies were limited by small sample sizes and lacked statistical significance.19,20 After the implementation of a patient navigation program at an urban safety net hospital, navigated patients had shorter times on average from symptom presentation to treatment by a median of 9 days.22 Although navigated patients had shorter time to treatment by a median of 12 days from abnormal mammogram in a poor and underinsured/uninsured patient population25 and by a mean of 4 days from cancer diagnosis in a predominantly white, privately insured sample,24 the differences were not statistically significant. Time from initiation to completion of primary treatment and from treatment completion to initiation of adjuvant therapy were also assessed,18,22 but patient navigation was not associated with significant reductions.

Treatment adherence.

Six patient navigation interventions16,17,21,23,26,28 aimed to improve adherence to breast cancer treatment mostly presented nonsignificant results. Treatment adherence was operationalized as the receipt of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy. Two of these studies conducted RCTs to examine the effectiveness of patient navigation in improving treatment adherence among patients with breast cancer who required adjuvant therapy. Specifically, Ell et al21 evaluated a culturally tailored patient navigation program that included in-person and/or telephone-based navigation services in a predominantly Hispanic/Latina, Spanish-speaking, and unemployed population with public/government health insurance. Bickell et al16 evaluated an intervention that connected patients who required postsurgical adjuvant treatment to targeted, high-quality, community-based cancer assistance programs in a predominantly privately insured patient population. Both RCTs found no significant differences in treatment adherence between patients with breast cancer who received navigation services (intervention) or usual care plus written informational materials (control).16,21 However, both intervention and control groups had high overall adherence rates of radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy (range, 86% to 93%).

Patient adherence to radiation, chemotherapy, and hormonal therapy was also evaluated through breast cancer care quality indicators17,28 from the ASCO National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality31 and standard cancer treatment recommendations23,26 from ASCO/NCCN guidelines.32 Accordingly, treatment adherence was specified as the receipt of radiation therapy in women who had breast-conserving surgery17,23,26,28 and were younger than 70 years,23 receipt of chemotherapy in women younger than 50 years17,23,28 or in women younger than 70 years with estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative breast cancer,23,26 and receipt of hormonal therapy for women with estrogen and/or progesterone receptor–positive breast cancer.17,23,26,28 Although one study reported that navigated patients were more likely to receive hormonal therapy than non-navigated patients,23 patient navigation was not significantly associated with receipt of radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy in a predominantly Hispanic/Latina, Spanish-speaking, and uninsured patient population17 or among African American/black and white patients with breast cancer.23,28 Similarly, another study reported comparable treatment rates between navigated patients and NCCN patients,26 which were not statistically different, and the specific details of the interventions that NCCN patients received were unclear.

Adherence to surveillance mammography.

Two studies17,28 evaluated a survivorship outcome, which was adherence to post-treatment surveillance guidelines. On the basis of ASCO clinical recommendations,31 patients with noninvasive breast cancer (stage I to III) should obtain a mammogram after curative treatment within 12 months. Both studies reported that surveillance mammography rates were significantly higher among navigated patients by 24%17 and 27%28 (P < .05).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the most comprehensive systematic review of patient navigation research focused on breast cancer treatment and survivorship outcomes to date. The study improved on previous narrative and systematic reviews by conducting searches in multiple electronic databases, which extended the search to cover 25 years, and evaluated the quality of research conducted. This review identified an increase in the number of patient navigation programs for breast cancer, including the number of studies that evaluated treatment and survivorship outcomes, as well as the implementation of patient navigation in medically underserved populations. Consistent with the original purpose of patient navigation,11,33 most studies16-23,26-28 targeted ethnic minorities and/or those with limited or without health insurance. The findings of this systematic review indicate there is significant heterogeneity in patient navigation programs in terms of the delivery of intervention, navigation goals and services, personnel who provided navigation, intended audiences, and targeted outcomes. The research that has evaluated the efficacy of patient navigation for breast cancer treatment and survivorship was of moderate quality, and the findings are mixed.

The primary outcomes targeted were timeliness of treatment initiation, adherence to cancer treatment, and adherence to surveillance mammography. Although all studies assessed the outcome variables by extracting data from medical records, they varied in the operationalization and measurement of these outcomes, which made it impossible to conduct a meta-analysis. In general, limited evidence suggested that patient navigation improves treatment outcomes in women with breast cancer. Although there was some indication that those who received patient navigation had statistically significant fewer days from diagnosis to treatment initiation compared with a control group in two studies (control v intervention, 74 v 5718 and 48 v 2227), other studies reported no significant benefit.19,20,24,25 The two studies18,27 that reported significant improvements targeted Hispanic/Latina and African American/black populations that were predominantly insured through local government insurance, which suggests that patient navigation may be effective in improving cancer treatment initiation among medically underserved populations. The receipt of treatment < 60 days from diagnosis is clinically significant, because treatment delays ≥ 60 days are associated with higher risks of overall and breast cancer–related death.6 In all but one treatment initiation study, both navigated and non-navigated patients on average initiated treatment within the recommended 60 days19,20,22,24,25,27; therefore, whether patient navigation had a clinically significant impact on treatment initiation or breast cancer disparities is not clear. Finally, many studies found that patient navigation did not significantly improve adherence to breast cancer treatments,16,17,21,23,28 although navigated patients were more likely to receive recommended hormonal treatments than control subjects in one study.23 Because of the paucity of studies, results on the efficacy of patient navigation in improving treatment outcomes remain unclear. With regard to breast cancer survivorship, two studies demonstrated greater adherence to post-treatment surveillance among navigated patients who had significantly higher rates of annual surveillance mammograms than non-navigated patients (intervention v control, 76% v 52%17 and 81% v 54%28). Although additional experimental studies are needed to substantiate the patient navigation effects in survivorship, this finding agrees with previous research, which has consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of patient navigation at increasing cancer screening rates.9,10,12

The findings from this review have significant implications for the delivery of breast cancer care. Specifically, the limited evidence of patient navigation in improving breast cancer treatment and survivorship outcomes underscores the need for additional studies and evaluation before using patient navigation as part of standard oncology care. A growing movement has integrated patient navigation into cancer treatment and survivorship care despite equivocal evidence of its efficacy. Since 1990,13 hundreds of patient navigation programs have been implemented across the United States.34 In addition, as of 2015, cancer centers are required to have a patient navigation process in place for accreditation by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer.35 However, research has yet to establish the effectiveness of patient navigation after patients have received a breast cancer diagnosis. In only one study18 was a significant difference found between the patient navigation and control groups in which time to treatment from diagnosis was < 60 days in navigated patients and significantly different and > 60 days in control subjects. And the strongest evidence to indicate that patient navigation is helpful in improving adherence to surveillance mammography comes from two retrospective observational studies,17,28 which have a higher likelihood of bias and confounding than RCTs. Although most patients would benefit from additional assistance, whether patient navigation has a clinical benefit in those with breast cancer and in survivors is unclear. Also not clear is whether patient navigation is cost-effective in improving outcomes in breast cancer treatment and survivorship. A cost-benefit analysis of patient navigation compared with usual care indicated that patient navigation was borderline cost-effective at $95,625 per life-year saved if navigated patients received a definite diagnosis of breast cancer 6 months earlier.36 However, the costs of navigating patients with breast cancer during cancer treatment and the survival benefits of treatment adherence (eg, reduced treatment delays, interruptions, incompletions) in terms of cost savings have not yet been evaluated.

This review has several limitations. Most study participants were middle-age. However, this is consistent with national statistics of increasing breast cancer incidence rates in women older than 50 years, with 79% of new cases in this age-group.37 The search was limited to studies conducted in the United States and published in English-language peer-reviewed academic journals. Gray literature was also excluded; therefore, conference abstracts or unpublished studies were not obtained. In addition, studies that combined and analyzed breast cancer with other types of cancers were excluded from the review, although they may have evaluated treatment and survivorship outcomes. Consequently, the review may not have included all patient navigation studies in breast cancer. Furthermore, the diversity in interventions and small number of identified studies likely limit the generalizability of findings. Finally, a quantitative analysis of the findings was not conducted because of the heterogeneity of assessment and evaluation of outcomes. The lack of consistent assessment and reporting of treatment outcomes further limit the generalizability of results.

Although growing support exists for patient navigation in cancer care, additional research is needed to determine the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of patient navigation in breast cancer treatment and survivorship. Future research should compare various models of patient navigation with the same outcomes and should adhere to the recommended metrics38,39 and patient-reported outcomes40 for evaluating patient navigation during treatment and survivorship, which will facilitate comparisons across programs and a meta-analysis. Table 4 lists breast cancer treatment and survivorship outcomes based on previous recommendations.38-40 In addition, a more rigorous evaluation of patient navigation interventions is needed. To date, there has been a lack of RCTs that examine the efficacy of patient navigation in treatment and survivorship outcomes, and much of the research has lacked a concurrent control group. Future research should be prospective and have a concurrent control group. To increase generalizability of findings, studies should recruit larger, ethnically diverse samples and evaluate whether programs equally benefit all racial and ethnic groups. Patient navigation research also lacks longitudinal studies that evaluate the long-term effects of patient navigation on improving clinical outcomes. Future studies should include longer follow-up of patients with breast cancer for at least 5 years postnavigation and track the recurrence of cancer and survival data. Future research should also examine the processes by which patient navigation improves specific cancer-related goals to determine the components of the intervention that are most likely to be associated with timely, high-quality, and recommended treatment or survivorship care and survival from breast cancer.

Table 4.

Metrics for Evaluating Patient Navigation During Breast Cancer Treatment and Survivorship

| Domain | Metric | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Timeliness of care | Cancer diagnosis date to first treatment date | Time in number of days between dates |

| Oncology provider consultation date to first treatment date | Time in number of days between dates | |

| Percentage with treatment initiation | Percentage of patients who initiated treatment within 30, 60, and 90 days | |

| Time intervals between treatment modalities (eg, surgery to radiation/chemotherapy, radiation to surgery/chemotherapy, chemotherapy to hormone therapy) | Time in number of days between dates | |

| Concordant start dates of treatments (eg, radiation and chemotherapy) | Yes/no | |

| Treatment adherence | Recommended surgery performed | Yes/no |

| Recommended chemotherapy received/completed | Yes/no | |

| Recommended radiation therapy received/completed | Yes/no | |

| Recommended hormone therapy received/completed | Yes/no | |

| Chemotherapy treatments missed | Number of chemotherapy cycles missed/omitted | |

| Radiation treatments missed | Number of days radiation therapy treatments missed | |

| Treatment appointments missed | Number of days on-treatment appointments missed | |

| Guideline adherence | Standard of care delivered; adherence to NCCN guidelines | Yes/no |

| Health care utilization/care coordination | Unplanned hospitalizations; emergency department visits | Number of (preventable) hospitalizations or emergency department visits during and after cancer treatments |

| Ancillary services (eg, social work, psychologic/psychiatric therapy, physical therapy, nutrition) recommended/received | Yes/no | |

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||

| Patient satisfaction | ||

| Cancer-related care | Patient Satisfaction with Cancer Care (PSCC)41 | An 18-item measure of patient satisfaction with diagnostic/therapeutic cancer-related care |

| Navigation | Patient Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationship with Navigator (PSN-I)42 | A nine-item measure of patient satisfaction with navigator |

| Quality of life | Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy for Breast Cancer (FACT-B)43 | A 44-item measure of physical well-being, social/family well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, relationship with physician, and additional concerns in patients with breast cancer |

| Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement System (PROMIS)-2944 | A 29-item measure of physical, mental, and social health, which assesses seven domains (depression, anxiety, physical function, pain interference, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and ability to participate in social roles and activities) | |

| Impact of Event Scale (IES)45 | A 15-item measure of subjective distress that results from exposure to major life events |

NOTE. Adapted from recommendations for metrics to evaluate patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment by Guadagnolo et al38 (Tables 1 and 2), recommended survivorship navigation outcome measures by Pratt-Chapman et al39 (Table 1), and recommended patient-reported outcomes to assess patient navigation by Fiscella et al40 (Table 1).

Abbreviation: NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network

Despite widespread implementation of patient navigation programs for patients with breast cancer and survivors, there is no conclusive evidence with regard to the efficacy of these programs. Two retrospective observational studies indicate that patient navigation may be effective for surveillance mammography. To enable comparison across studies, additional high-quality, prospective research with concurrent control groups are needed that use the same outcomes as previous studies.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R21CA161077 to K.J.W.).

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Authors’ disclosures of potential conflicts of interest are found in the article online at www.jco.org. Author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: All authors

Collection and assembly of data: Sharon H. Baik

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Patient Navigation in Breast Cancer Treatment and Survivorship: A Systematic Review

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or jco.ascopubs.org/site/ifc.

Sharon H. Baik

No relationship to disclose

Linda C. Gallo

No relationship to disclose

Kristen J. Wells

No relationship to disclose

REFERENCES

- 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23800. Brawley OW, Berger MZ: Cancer and disparities in health: Perspectives on health statistics and research questions. Cancer 113:1744-1754, 2008 (suppl 7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Byers T. Two decades of declining cancer mortality: Progress with disparity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:121–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.121208.131047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dohan D, Schrag D. Using navigators to improve care of underserved patients: Current practices and approaches. Cancer. 2005;104:848–855. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandelblatt JS, Yabroff KR, Kerner JF. Equitable access to cancer services: A review of barriers to quality care. Cancer. 1999;86:2378–2390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yabroff KR, Washington KS, Leader A, et al. Is the promise of cancer-screening programs being compromised? Quality of follow-up care after abnormal screening results. Med Care Res Rev. 2003;60:294–331. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McLaughlin JM, Anderson RT, Ferketich AK, et al. Effect on survival of longer intervals between confirmed diagnosis and treatment initiation among low-income women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4493–4500. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.39.7695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kothari A, Fentiman IS. 22. Diagnostic delays in breast cancer and impact on survival. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57:200–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26262. Freeman HP, Rodriguez RL: History and principles of patient navigation. Cancer 117:3539-3542, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells KJ, Battaglia TA, Dudley DJ, et al. Patient navigation: State of the art or is it science. Cancer. 2008;113:1999–2010. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paskett ED, Harrop JP, Wells KJ. Patient navigation: An update on the state of the science. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:237–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freeman HP. The origin, evolution, and principles of patient navigation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1614–1617. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson-White S, Conroy B, Slavish KH, et al. Patient navigation in breast cancer: A systematic review. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33:127–140. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181c40401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freeman HP, Muth BJ, Kerner JF. Expanding access to cancer screening and clinical follow-up among the medically underserved. Cancer Pract. 1995;3:19–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feuerstein M. Defining cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:5–7. doi: 10.1007/s11764-006-0002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Effective Public Health Practice Project . Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, : Effective Public Health Practice Project; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bickell NA, Geduld AN, Joseph KA, et al. Do community-based patient assistance programs affect the treatment and well-being of patients with breast cancer? J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:48–54. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen F, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Improving breast cancer quality of care with the use of patient navigators. Am Surg. 2010;76:1043–1046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dudley DJ, Drake J, Quinlan J, et al. Beneficial effects of a combined navigator/promotora approach for Hispanic women diagnosed with breast abnormalities. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1639–1644. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ell K, Padgett D, Vourlekis B, et al. Abnormal mammogram follow-up: A pilot study women with low income. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:130–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.103009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, et al. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: A on the basis of clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Xie B, et al. Cancer treatment adherence among low-income women with breast or gynecologic cancer: A on the basis of controlled trial of patient navigation. Cancer. 2009;115:4606–4615. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haideri NA, Moormeier JA. Impact of patient navigation from diagnosis to treatment in an urban safety net breast cancer population. J Cancer. 2011;2:467–473. doi: 10.7150/jca.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ko NY, Darnell JS, Calhoun E, et al. Can patient navigation improve receipt of recommended breast cancer care? Evidence from the National Patient Navigation Research Program. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2758–2764. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.6037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koh C, Nelson JM, Cook PF. Evaluation of a patient navigation program. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011;15:41–48. doi: 10.1188/11.CJON.41-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobb R, Allen JD, Emmons KM, et al. Timely care after an abnormal mammogram among low-income women in a public breast cancer screening program. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:521–528. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raj A, Ko N, Battaglia TA, et al. Patient navigation for underserved patients diagnosed with breast cancer. Oncologist. 2012;17:1027–1031. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramirez A, Perez-Stable E, Penedo F, et al. Reducing time-to-treatment in underserved Latinas with breast cancer: The Six Cities Study. Cancer. 2014;120:752–760. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weber JJ, Mascarenhas DC, Bellin LS, et al. Patient navigation and the quality of breast cancer care: An analysis of the breast cancer care quality indicators. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:3251–3256. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2527-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freund KM, Battaglia TA, Calhoun E, et al. National Cancer Institute Patient Navigation Research Program: Methods, protocol, and measures. Cancer. 2008;113:3391–3399. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calhoun EA, Whitley EM, Esparza A, et al. A national patient navigator training program. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11:205–215. doi: 10.1177/1524839908323521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, et al. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: How can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:626–634. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desch CE, McNiff KK, Schneider EC, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/National Comprehensive Cancer Network Quality Measures. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3631–3637. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.5068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Freeman HP. Patient navigation as a targeted intervention: For patients at high risk for delays in cancer care. Cancer. 2015;121:3930–3932. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hede K. Agencies look to patient navigators to reduce cancer care disparities. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:157–159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Commission on Cancer: Cancer Program Standards: Ensuring Patient-Centered Care. Chicago, IL, American College of Surgeons, 2012.

- 36.Markossian TW, Calhoun EA. Are breast cancer navigation programs cost-effective? Evidence from the Chicago Cancer Navigation Project. Health Policy. 2011;99:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.American Cancer Society . Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2013-2014. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26269. Guadagnolo BA, Dohan D, Raich P: Metrics for evaluating patient navigation during cancer diagnosis and treatment: Crafting a policy-relevant research agenda for patient navigation in cancer care. Cancer 117:3565-3574, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26261. Pratt-Chapman M, Simon MA, Patterson AK, et al: Survivorship navigation outcome measures: A report from the ACS patient navigation working group on survivorship navigation. Cancer 117: 3575-3584, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26260. Fiscella K, Ransom S, Jean-Pierre P, et al: Patient-reported outcome measures suitable to assessment of patient navigation. Cancer 1173603-3617, 2011 (suppl 15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Freund KM, et al. Structural and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with cancer-related care measure: A multisite patient navigation research program study. Cancer. 2011;117:854–861. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Winters PC, et al. Psychometric development and reliability analysis of a patient satisfaction with interpersonal relationship with navigator measure: A multi-site patient navigation research program study. Psychooncology. 2012;21:986–992. doi: 10.1002/pon.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al: Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol 15:974-986, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44. PROMIS Health Organization, PROMIS Cooperative Group: PROMIS-29 version 2.0 2008-2013. http://www.healthmeasures.net/administrator/components/com_instruments/uploads/15-09-02_02-16-11_PROMIS-29Profilev2.0InvestigatorVersion.pdf.

- 45.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]