Abstract

Purpose

This qualitative study of survivors of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) for hematologic malignancy explored attitudes about late effects of therapy, healthcare issues and information needs.

Methods

We conducted 12 in-depth cognitive interviews and 3 focus groups of patients who had previously had SCT and were without recurrence of their primary disease. We used grounded theory methods, where themes emerged from consensus between co-coders. Health-related quality of life was assessed with the Short-Form (SF-36).

Results

The study included 22 patients (50% female; 95% white; mean age 47 years). The mean time from SCT was 5.2 years (±1.4 years). Most had low SF-36 scores. Participants discussed late effects of therapy, most commonly graft-versus-host disease, and how they impacted their quality of life. They reported frequent healthcare use and cancer screening after SCT and discussed problems affording care and interacting with insurance companies. Participants shared sources of health information (e.g., preferring providers as their primary sources of information, but also learned from websites, medical journals, and peer experiences) and identified information barriers (e.g., feeling “on their own” insofar as they did not have targeted care for their needs), and expressed importance of anticipatory guidance regarding infertility. Overall, participants’ personal issues and social influences impacted survivors’ needs and attitudes.

Conclusions

SCT survivors face continuing and lasting health effects. The factors impacting survivorship needs are complex and may be interrelated. Future research should study the affect of incorporating personal and social issues into existing clinical SCT programs on survivors’ quality of life.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship, stem cell transplantation, qualitative research

Adult cancer survivors of allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) face long-term effects of their treatment. Approximately half of these patients survive ten years after treatment [1]. Survivors report experiencing pain, memory and concentration problems, psychological distress, and problems with sexual functioning and fertility [2–4]. They are also at risk of disease recurrence, infections, hormonal deficiencies, subsequent malignancy, and mortality [5–7]. Many develop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), a complication wherein white blood cells of transplanted tissue attack the recipient’s skin, mucosa, liver and gastrointestinal tract [3,8–12]. Survivors report anxiety, depression, difficulties reentering school and workplace, [5,13] and low satisfaction with their general health, physical condition, and sexual relationships [2,4,14].

Several studies have examined quality of life issues for long-term survivors of SCT. Typical late effects include GVHD with involvement of skin, liver and oral mucosa [1]. Survivors’ health-related quality of life, including reductions of fatigue, anxiety and depression, improves more in the short-term than long-term [15]. Challenges lasting more than a month after transplantation included physical health and functioning, social and psychological adjustment, and low household income [14,16–19]. Cancer and transplant type might influence quality of life and intensity of late effects, post-transplant [17,20]. Regarding family and social life, significant levels of emotional, employment, and interpersonal distress as a result of their disease and treatment [21,22]. Studies of survivors’ health promotion prevention and screening behaviors found that survivors participate in physical exams more than general population, but screening practices were similar [23,24].

Survivors’ level of self-efficacy impacts their ability to manage common post-SCT symptoms [25]. Scheduling problems, information gaps, and negative feelings about care impacted whether SCT survivors take advantage of mental health services [26]. Although SCT survivors reported an average of 4 medical problems (controls reported 2), denial of health insurance may prevent them from seeking care [27]. Since the number of long-term survivors is anticipated to rise given the increasing use of allogeneic SCT, these issues may become more problematic [28]. Prior studies of surveys or randomized controlled trials have not conceptually explained the causes and connections between these problems. This qualitative publication explores the attitudes of long-term survivors of SCT for hematologic malignancies about their healthcare use and information needs for the purposes of contributes to the body of knowledge by offering a model for explaining the relationship between the factors.

METHODS

We identified potential participants from The University of Texas MD Anderson SCT Registries which include all patients who received a SCT at our institution. We included adult survivors who underwent an initial allogeneic SCT between 2000 and 2005, resided in Texas, and had the ability to speak English. We mailed eligible patients an invitation to participate in a focus group (FG) or interview. From the pool of willing participants, we conducted three 2-hour FGs and twelve 1-hour interviews. Each FG contained 3 to 4 participants, an optimal number for an intimate, comfortable setting for discussion and to retain variety of ideas generated [29,30]. We used interviews for participants who could not travel or preferred one-on-one interviews instead of group meetings. Trained moderators conducted all FGs and interviews. No moderator had previously met or provided care for any participants. A script was used by moderators with open-ended, guiding questions about participants’ current health status, lifestyle issues, late effects of cancer treatment, healthcare use, current health screening practices, and perceived healthcare and information needs (Table 1) We audio-recorded and transcribed the discussions, and imported transcripts into NVivo©, a software that assists in coding, enumerating frequencies, and running queries to investigate relationships between codes.

Table 1.

Guiding Questions

Current Health Status

|

Lifestyle Issues

|

Late Effects of Cancer Treatment

|

Healthcare Use

|

Perceived Healthcare Needs

|

Current Health Screening Practices

|

Perceived Information Needs

|

We used a grounded theory approach to conduct a thematic analysis of the transcripts to ensure thorough coding processes based on cross-checking and consensus building and develop a conceptual model for an integrative explanation of the multiple factors at play [31,32].. Three phases comprise the grounded theory coding process: (1) Open coding phase, wherein two team members independently reviewed and coded interview and FG transcripts, then met to discuss additional themes that emerged, compare codes, and reach consensus; (2) Axial coding stage, wherein we streamlined the coding schema by merging similar codes, removing duplicates, and categorizing codes by themes; and (3) Selective coding stage, where we discussed relationships between themes and the framework connecting them. To ensure that our data achieved theoretical saturation, a constant comparison method was implemented, where we tested and used our axial coding categories on all subsequent transcripts [31,32]. Conceptual themes were organized into five categories: late effects, healthcare, health education and outreach, personal factors, and social factors. By the end of our comparison analysis, no new themes had emerged. Theoretical saturation was confirmed by consensus. A single quotation could encompass several emerging themes. Further, participants often offered more than one response on a topic during discussion. Therefore, the final number of or quotes was less than the final number of codes. All participants completed a demographic form and the Short-Form 36 (SF-36). Raw scale scores were converted to 0–100 scales, with higher scores indicating higher function or well-being [33]. The study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Two hundred and fifty three patients had SCT between 2000 to 2005. Of these, 26% (n=65) were alive in 2007. Of the 65 who were alive, 5 patients had incorrect addresses and could not be contacted. Additionally, 7 patients were ineligible due to language (n=6) and being in the terminal phase of their illness (n=1). Three were no longer current residents of Texas. One patient refused further contact, and 13 patients could not be reached, resulting in 36 eligible, of whom 22 agreed to participate. The duration of time from their SCT to the interview ranged from 2.4 – 8 years with a mean of 5.2 years (±1.4 years). Participants’ characteristics and SF-36 scores are shown in Table 2. Most participants had scores lower than 50. Table 3 shows the conceptual themes that emerged from our analysis in five categories: late effects, healthcare issues, health education and outreach, personal factors, and social factors.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | n=22 | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean (range) | 47 (22–69) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 11 | (50%) |

| Female | 11 | (50%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 21 | (95.5%) |

| Native American | 1 | (4.5%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic | 18 | (81.8%) |

| Hispanic | 4 | (18.2%) |

| Cancer | ||

| AML | 19 | (86.4%) |

| MDS | 2 | (9.1%) |

| APL | 1 | (4.5%) |

| Time since SCT | ||

| Mean years ± SD (range) | 5.2 ± 1.4 (2.4–8.0) | |

| Education | ||

| High school diploma | 3 | (13.6%) |

| Trade school | 1 | (4.5%) |

| Some college | 7 | (31.8%) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 5 | (22.7%) |

| Advanced degree | 6 | (27.3%) |

| Employment1 | ||

| Working2 | 8 | (36.4%) |

| Not Working3 | 9 | (40.9%) |

| Disabled | 6 | (27.3%) |

| Insurance1 | ||

| None | 2 | (9.1%) |

| HMO | 4 | (18.2%) |

| PPO | 7 | (31.8%) |

| Medicaid | 2 | (9.1%) |

| Medicare | 10 | (45.5%) |

| Income | ||

| <$24,999 | 7 | (31.8%) |

| $25,000–49,999 | 5 | (22.7%) |

| $50,000–99,999 | 3 | (13.6%) |

| ≥$100,000 | 4 | (18.2%) |

| Refused to answer | 3 | (13.6%) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 5 | (22.7%) |

| Married | 10 | (45.5%) |

| Divorced | 7 | (31.8%) |

| Current Comorbid Conditions | ||

| Chronic Lung Disease | 5 | (22.7%) |

| Blindness/Trouble Seeing | 6 | (27.3%) |

| Deafness/Trouble Hearing | 4 | (18.2%) |

| Diabetes | 2 | (9.1%) |

| Asthma | 4 | (18.2%) |

| Ulcer or GI bleeding | 1 | (4.5%) |

| Arthritis or rheumatism | 7 | (31.8%) |

| Sciatica/Chronic back problems | 2 | (9.1%) |

| Number of Comorbidities | ||

| 0 | 8 | (36.4%) |

| 1 | 6 | (27.3%) |

| 2 | 3 | (13.6%) |

| 3 | 3 | (13.6%) |

| 5 | 2 | (9.1%) |

| SF-36 Summary Scale, mean score +/− SD | ||

| Physical Component Summary | 43.5 ± 13.6 | |

| Mental Component Summary | 49.2 ± 12.6 | |

| SF-36 Subscale, mean score +/− SD | ||

| Physical Functioning | 43.5 ± 12.7 | |

| Role Functioning (Physical) | 42.6 ± 17.0 | |

| Bodily Pain | 50.8 ± 11.6 | |

| General Health | 42.3 ± 13.1 | |

| Vitality | 46.8 ± 13.7 | |

| Social Functioning | 45.2 ± 12.1 | |

| Role Functioning (Emotional) | 46.0 ± 17.0 | |

| Mental Health | 51.2 ± 11.2 | |

Total numbers may exceed 22 because some participants chose more than one response.

Includes full-time workers (n=5), part-time workers (n=2), and homemakers (n=1).

Includes those who are unemployed (n=1), students (n=1), and retirees (n=7).

Table 3.

Most Frequent Themes

| Categories | Codes | Code Definition | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Late Effects | Listing late effects | Stories about the effects of treatment and residual symptoms and complications | 210 |

| Experiencing GVHD | Details about how GVHD affects health, comorbidities, and quality of life | 86 | |

| Feeling uncertain about late effects | Concerns and confusion about the cause, duration and extent of late effects | 42 | |

| Healthcare | Valuing the patient-provider relationship | Evaluations of their relationship and communication with providers | 214 |

| Covering expenses | Discussion about affording the financial cost of healthcare. Evaluations of insurance coverage, and stories about the changes in coverage | 124 | |

| Frequenting healthcare services | Descriptions of how often and for what purpose they use healthcare services | 63 | |

| Making healthcare decisions | Discussions of how they participate in making decisions about their health and treatment | 56 | |

| Participating in screening | Descriptions of screenings and evaluations of screening practices | 51 | |

| Making appointments | Anecdotes about the frequency and logistics of scheduling and attending provider visits | 49 | |

| Health Education and Outreach | Describing information sources | Reports about where and from whom survivors find information about their health condition and needs | 140 |

| Identifying information barriers | Lingering questions and concerns about late effects and health prognoses | 71 | |

| Personal Factors | Changing activities | Anecdotes about adjustments and changes made in how survivors conduct their daily lives | 89 |

| Using home remedies | When participants use over-the-counter, complementary and alternative treatments, and other alternatives | 56 | |

| Social Factors | Letting others influence you | Stories about interactions with and experiences of others that shape their own health attitudes and behaviors | 98 |

| Getting support from others | When friends, family members, peers and care providers help in survivorship care | 63 | |

| Health affecting relationships | Stories about late effects impacting the relationship with families, friends and others—for better or worse | 54 |

Late Effects and GVHD

Participants experienced a range of late effects including fatigue, pain, nausea, neuropathy, “chemo brain,” and GVHD which affected their eyes, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and other organs. Some participants misunderstood the cause of GVHD; they thought their bodies were attacking the transplanted cells, instead of the transplanted cells attacking their organs.

“GVHD is graft versus host disease, or your body reacting to the…foreign substance in your body.” (Male, age 36)

Questions lingered whether symptoms would subside or worsen.

“[W]hat complications am I going be facing…in my lifetime?…Is my [GVHD] going to get worse with my eyesight?” (Male, age 49)

Participants also described late effects that impacted their quality of life and social lives, including sexual dysfunction. Taking preventative steps prevented them from socializing and participating in some group activities.

“I don’t really have a sex drive anymore.” (Female, age 53)

“When you shake hands or you do something with your hands, [you] just consider it dirty. And it changes your lifestyle but it also keeps you a lot healthier.” (Male, age 69)

Healthcare Issues

Participants reported frequent healthcare use and participation in screening for recurrences or second cancers. They valued the patient-provider relationship and described their role in the health decision-making. Using the healthcare system often exposed our participants to many of its flaws. Financial expense and frequency of appointments posed problems for them.

Participating in screening

On whole, participants also felt that they participated in appropriate screening, including colonoscopies, bone marrow biopsies, blood tests, bone density tests, chest x-rays, and CAT scans.

“I feel very covered. I feel very safe in [how much] screening they do.” (Male, age 29)

Fears of recurrence fueled a few participants to suspect that they might not participate in enough screenings.

“If you did less [screening], you’ll always have that in your head, ‘ [Do] I have something?’ Once you have cancer you’re always thinking …do I have it again.” (Female, age 52)

Valuing the patient-provider relationship

Patients valued providers as sources of information, and they trusted their directives. However, they often wanted more interaction with cancer specialists who helped them during treatment. And many described encountering nonspecialists who they believed were not as informed or helpful in addressing their needs.

“I feel very comfortable [with the cancer specialists]--like they really do care about you. [O]ne year I got real sick, and I ended up going to a [non-cancer specialist]. And they made me feel like they weren’t solving the problem.” (Male, age 49)

Making healthcare decisions

Participants described the importance of participating in their healthcare decision-making, e.g., asking questions, making requests, and keeping personal health journals.

“Doctors should listen to [patients], and if they say ‘check my blood,’ they should check the blood, because I could have died.” (Female, age 54)

Many were motivated to research for themselves their symptoms and treatments.

“I normally just kind of go WebMD and self-diagnose.” (Female, age 49)

Covering expenses

Many participants were satisfied with how their insurance met their healthcare needs. However, some reported that they no longer had health insurance coverage.

“I don’t know of a company in the world that will affordably give you health care when you’re diagnosed terminal.” (Female, age 27)

Still others reported that, despite insurance, their costs could be prohibitive.

“Having to go to the doctor so many times…my out-of-pocket spending is just so much.” (Female, age 40)

Participants described how physical disability from cancer and treatments caused job loss and, in turn, made their financial situation difficult.

“[W]hen I lost my job…we were paying extreme amounts of money to hold the insurance together, like nine hundred a month.” (Female, age 54)

Making appointments

Participants described how difficult it was to manage the logistics of making appointments with multiple providers.

“They always schedule my appointments on top of each other so, you know, sometimes…I’m here all day.” (Female, age 22)

Often it required taking time off from work for themselves and their care providers in order to accommodate appointments.

“I see my [eye doctor and a doctor for] GVHD… [Appointments] pile up during the day…I’m here from 8:00 in the morning until 4:00 in the afternoon… [Y]ou just get tired of waiting and sitting.” (Male, age 23)

Health Education and Outreach

Participants shared their sources of health information and their gaps in knowledge.

Information sources

Participants reported medical providers served as primary sources of information.

“I had a fabulous oncologist, and I had her sit down and explain everything--the side effects, the AML--just explain it to me where I can understand it.” (Male, age 51)

Family members and their use of the Internet were also reported to be sources of support and information.

“My mother’s my advocate. She belongs to…leukemia groups. And they talk. She has friends online.” (Female, age 49)

“[M]y wife spends a lot of time on the Internet looking stuff up.” (Male, age 62)

Participants gathered information from various media, including the Internet, emails, patient education literature, and medical journals and periodicals.

“I will get magazines to study…I’ll read things like… [organization] Web sites and studies and things that they’ve done there.” (Female, age 27)

One participant desired more online outlets for interacting with peers for support. (Male, age 51)

“[M]aybe there could be…a patient blog or [social network]…where people could put in their comments and then others can chime in.” (Male, age 62)

Identifying information barriers

Participants wanted to know more about the spectrum of expected late effects and best methods for mitigating them.

“[I would] like information about … life expectancy--I guess taking--like my medications, how many years can I take it without doing damage to my body.” (Male, age 49)

Some wished that more information about late effects of infertility had been given prior to SCT.

“ [I]t’s one thing to get for a woman to get her tubes tied and decide [she doesn’t] want any children. But when that gets stripped away from you, it’s completely different…I was single…I was short on time, [so I was treated] without having time to go harvest my eggs…I wasn’t aware I was on a time crunch.” (Female, age 40)

Many wanted information from peers regarding the particulars of their personal experiences with late effects.

“I would want to know more about the real-life problems that people have besides me.” (Female, age 53)

Others admitted that avoiding information helped curb the stress and fear that can accompany knowing every possible risk and harm.

“[S]ometimes, the less you know, the less you worry about.” (Male, age 62)

Many participants felt that they could not find the information and services that they needed. They felt left out by the system targeting patients with cancer currently undergoing treatment, rather than for people dealing with late effects after treatment.

“I’ll call cancer care and I’ll Google the cancer patient resources. There is help, but only for people in treatment. It’s like they’ve forgotten the people after they’ve survived.” (Female, age 40)

Personal Factors

Managing late effects required behavioral changes and adaptations to maintain personal health. Some sought additional treatments for mitigating symptoms above and beyond what healthcare providers prescribed.

Changing activities

To manage late effects, participants made lifestyle adjustments such as diet modification.

“I can’t eat jalapeños as often as I used to. That’s a big thing…I eat them, anyway, and sometimes I regret it. But I have to eat them anyway.” (Female, age 53)

Many had to change their levels of physical activity, which interfered with participation in leisure activities.

“I don’t swim anymore. And I have kids. I have a five-year-old and an eleven-year-old. So yeah, that frustrates them.” (Male, age 41)

Participants also compared their current activity to levels prior to SCT. Some reported eating healthier and exercising more.

“I can go up ten flights of stairs nonstop…I’m just in really good shape…I think even better than before I was sick.” (Male, age 50).

Using home remedies

Participants often turned to alternative and complementary medicine.

“I am on a juice regimen of Xango. I drink that. It builds my immune system. I haven’t been sick or coughing or any of that, and my energy level is wonderful.” (Female, age 54)

Social Factors

Social networks influenced survivors’ own perception of treatment and care coordination. Survivors shared with family and friends the emotional and logistical burden of using healthcare services, which, in turn, impacted their relationships.

Letting others influence you

Family, friends and peers played a role in shaping participants’ attitudes about treatment. Participants often framed their understanding of treatments in terms of similar experiences of others in their social circles of influence.

“I’ve talked to people that have, you know, been through what I’ve been through. A lot of them made it; they’re all right. And you ask them different questions.” (Male, age 59).

They also felt frustrated about others’ struggles with and reactions to their condition.

“The family still treats me…with kid gloves.’Don’t do this. Don’t do [that].’ They worry. It frustrates me.” (Male, age 41)

Getting support from others

Participants also described how people in their network helped them attend medical appointments and keep track of their treatments. For the most part, family and friends ably cared for their needs.

“The biggest thing for me is my wife was my caregiver. [S [he was [my] single-handed caregiver throughout a long, long process.” (Male, age 62)

On rare occasions, their logistical support was less helpful than their emotional support.

“My brother was my caretaker. And God bless him. He’s a sweetheart. But he is an idiot when it comes to taking care of somebody.” (Female, age 63)

Health affecting relationships

The unique and often burdensome circumstances of managing health impacted the relationships between survivors and their social network. Often, difficulties drew families and friends closer together.

“[I]t probably brought us closer together… [My husband] was very supportive and very caring and took real good care of me.” (Female, age 53)

However, in some cases, the stresses of experiencing and managing late effects made relationships tense and frustrating.

“[T]he memory problems that I’ve had has been frustrating… My [family talks] about things that have happened or that we’ve done in the past that I have no memory of.” (Female, age 53)

Other less frequent themes included returning to work and cancer experiences in other family members. A few patients described positive attitudes and feelings such as independence and contentment, and no interferences with social life. Overall, participants were eager to share their attitudes and beliefs, and they demonstrated that healthcare needs were a major issue in their everyday lives, even 5 or more years after SCT.

DISCUSSION

Late effects, health care issues, outreach and education, and personal and social factors were important themes among our study participants. SCT survivors face continuing and lasting health effects, which in turn, impede their quality of life and ability to participate in healthcare decision-making [4,34]. Participants had lower SF-36 scores, indicating lower levels of functioning or well-being as compared to another study of survivors 2 years after allogeneic SCT, [28] and the difference may in part be due in our participants’ longer duration of time from SCT. Similar to findings in prior studies, our participants noted problems in coordination of care and access to knowledgeable specialists for individual toxicities [35]. They preferred care from SCT specialists and felt that other providers often did not understand the complexities of their condition. Survivors may require more information and guidance about the duration, range, and maintenance of late effects. Given the involvement of family, friends and care providers in researching disease and symptom information and informing survivors’ attitudes about care, outreach and education initiatives should target survivors and their support network. Furthermore, continuing medical education and closer coordination between specialists and primary care providers may help survivors better transition from cancer care to survivorship care [36,37].

Prior studies identified several barriers—including scheduling, emotional discomfort, unawareness of the range of services, and physical limitations and impairments—that prevent survivors from accessing mental health services [26,38]. Our findings confirmed many of these barriers. However, they also extended the list of barriers to include financial cost, provider unawareness, and the extent of support offered by survivors’ friends, family and care providers. Also, our findings suggest that survivors wanted more information about late effects sooner in the treatment and recovery process. They also want more peer-to-peer information exchanges. Studies suggest that SCT survivors may be able to recover many aspects of quality of life over time, including physical strength, psychological and emotional health [39]. However, our findings suggest that some of these issues persist as long-term effects, and that survivors would benefit from evidence-based patient education on the duration and range of severity of these longer-term issues.

SCT survivors enlisted several personal resources--family, friends, peers, medical providers, online and traditional venues--to better understand and mitigate their condition [35,40]. Since SCT patients frequently use mass media and peer interactions as sources of information, outreach programs should incorporate multimedia dissemination tools and informed peer support. Online social networking might be enlisted to help provide support for patients in remote locations or with unique combinations of late effects. Social media might also be advisable in accommodating patient to provider conferences, thereby reducing the frequency of face-to-face visits and associate costs and scheduling inconveniences. However, given the paucity of literature on the efficacy of such technology in health communication, more research and pilot programs should be conducted to help ground such interventions in evidence-based practice [38].

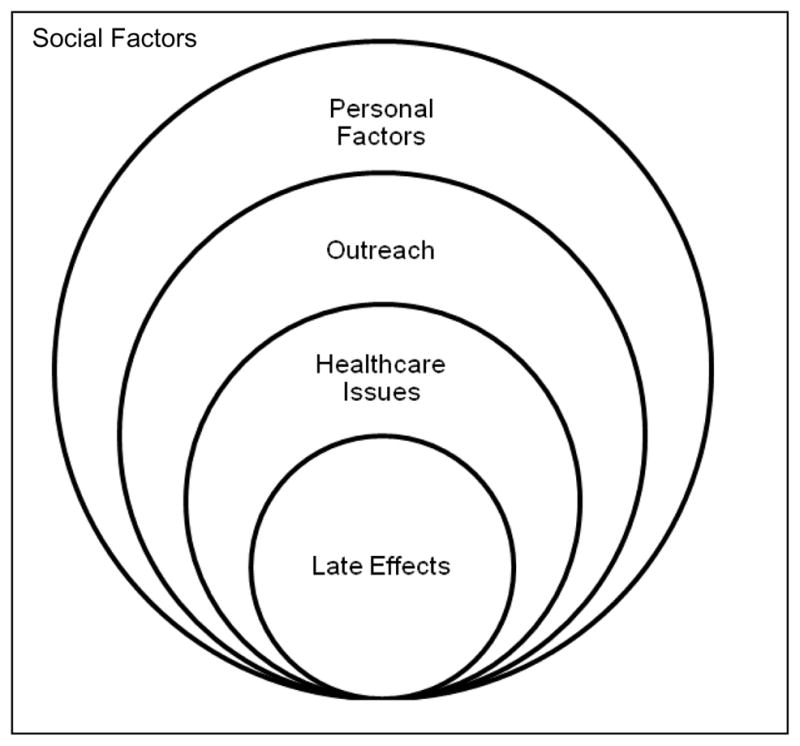

Our study contributes to the field by conceptualizing the relationship between the factors affecting survivors’ attitudes about care. We found a complex and mutual interrelationship between the factors that emerged from our study and factors reported in prior studies (see Figure 1). Late effects complicate survivors’ access to care, but so, too, do personal and social influences on attitudes about outreach and treatment. They looked to providers, family and friends for advice and examples of health behavior. Comparing their needs to those of others, seeking out health information, and experiencing financial barriers also influenced their attitudes about care. Furthermore, both interactions with others and personal priorities were important in influencing how they evaluated healthcare utilization and outreach. Late effects had consequences beyond healthcare; in turn, personal and social factors impacted healthcare attitudes and behaviors. Our conceptual model may help providers and educators better tailor treatment and health campaigns that are more sensitive to survivors’ needs.

Figure 1.

Our study is limited, as it evaluates a relatively small sample size and may not generalizable. Future studies might use larger samples to further investigate the causal links between reciprocally-related codes. Different themes and areas of concern might have surfaced in discussions with groups who were more ethnically and socioeconomically diverse. Additional studies should examine whether similar and consistent results emerge from a more heterogeneous population. Nevertheless, our study provides a helpful, preliminary assessment of survivors’ assessment of the healthcare system and their utilization and information needs. Our findings present new conceptual and practical domains that could prove useful in informing clinical practice, coordinating healthcare administration, and designing patient outreach and education.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the participating survivors and thank Susan C. Lackey, MPH for administrative support.

Funding

Dr. Hwang is a recipient of a National Cancer Institute Career Development Award (K07 CA132955). Dr. Suarez-Almazor holds a K24 Midcareer Investigator Award from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (K24 AR053593). This paper was presented in part at the 2011 Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer International Symposium in Athens, Greece.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. All primary data is under control of the authors and will be provided upon request.

References

- 1.Friedrichs B, Tichelli A, Bacigalupo A, et al. Long-term outcome and late effects in patients transplanted with mobilised blood or bone marrow: a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(4):331–8. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70352-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lof CM, Winiarski J, Giesecke A, et al. Health-related quality of life in adult survivors after paediatric allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;43(6):461–8. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sun K, Alvarez M, Ames E, et al. Mouse NK cell-mediated rejection of bone marrow allografts exhibits patterns consistent with Ly49 subset licensing. Blood. 2011 doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-374314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Rini C, et al. Quality of life concerns and depression among hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(9):1357–65. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0958-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayden PJ, Keogh F, Ni Conghaile M, et al. A single-centre assessment of long-term quality-of-life status after sibling allogeneic stem cell transplantation for chronic myeloid leukaemia in first chronic phase. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34(6):545–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatia S, Francisco L, Carter A, et al. Late mortality after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation and functional status of long-term survivors: report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2007;110(10):3784–92. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-082933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatia S. Long-term health impacts of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation inform recommendations for follow-up. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(4):437–52. doi: 10.1586/ehm.11.39. quiz 53–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baker KS, Gurney JG, Ness KK, et al. Late effects in survivors of chronic myeloid leukemia treated with hematopoietic cell transplantation: results from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2004;104(6):1898–906. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carpenter PA. Late effects of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2008;21(2):309–31. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2008.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser CJ, Bhatia S, Ness K, et al. Impact of chronic graft-versus-host disease on the health status of hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2006;108(8):2867–73. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanders JE. Chronic graft-versus-host disease and late effects after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Int J Hematol. 2002;76(Suppl 2):15–28. doi: 10.1007/BF03165081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingard JR, Vogelsang GB, Deeg HJ. Stem cell transplantation: supportive care and long-term complications. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2002:422–44. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2002.1.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrera M, Atenafu E, Pinto J. Behavioral, social, and educational outcomes after pediatric stem cell transplantation and related factors. Cancer. 2009;115(4):880–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrykowski MA, Bishop MM, Hahn EA, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life, growth, and spiritual well-being after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(3):599–608. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hjermstad MJ, Knobel H, Brinch L, et al. A prospective study of health-related quality of life, fatigue, anxiety and depression 3–5 years after stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2004;34(3):257–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1704561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson KO, Giralt SA, Mendoza TR, et al. Symptom burden in patients undergoing autologous stem-cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39(12):759–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrera M, Atenafu E, Hancock K. Longitudinal health-related quality of life outcomes and related factors after pediatric SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44(4):249–56. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bevans MF, Mitchell SA, Barrett AJ, et al. Function, adjustment, quality of life and symptoms (FAQS) in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) survivors: a study protocol. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun CL, Francisco L, Baker KS, et al. Adverse psychological outcomes in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study (BMTSS) Blood. 2011;118(17):4723–31. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-348730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong FL, Francisco L, Togawa K, et al. Long-term recovery after hematopoietic cell transplantation: predictors of quality-of-life concerns. Blood. 2010;115(12):2508–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris ME, Grant M, Lynch JC. Patient-reported family distress among long-term cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(1):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooke L, Gemmill R, Kravits K, et al. Psychological issues of stem cell transplant. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2009;25(2):139–50. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bishop MM, Lee SJ, Beaumont JL, et al. The preventive health behaviors of long-term survivors of cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation compared with matched controls. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(2):207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armenian SH, Sun CL, Francisco L, et al. Health behaviors and cancer screening practices in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT): a report from the BMT Survivor Study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47(2):283–90. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu LM, Austin J, Hamilton JG, et al. Self-efficacy beliefs mediate the relationship between subjective cognitive functioning and physical and mental well-being after hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Psychooncology. 2011 doi: 10.1002/pon.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mosher CE, DuHamel KN, Rini CM, et al. Barriers to mental health service use among hematopoietic SCT survivors. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(3):570–9. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syrjala KL, Langer SL, Abrams JR, et al. Late effects of hematopoietic cell transplantation among 10-year adult survivors compared with case-matched controls. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(27):6596–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.12.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Le RQ, Bevans M, Savani BN, et al. Favorable outcomes in patients surviving 5 or more years after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16(8):1162–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krueger R. Focus groups: a practical guide for applied research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DM . Successful focus groups: advancing the state of the art. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Strauss AC, Corbin J. Grounded theory in practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strauss AC, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ware J, Snow K, Kosinski M, et al. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: The Health Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stolar KR, Neumann J, Popat UR, et al. Identifying and addressing the long term needs of the adult allogeneic stem cell transplant (SCT) recipient through a survivorship clinical program. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2009;15(2, Supplement):144–45. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roundtree AK, Giordano SH, Price A, et al. Problems in transition and quality of care: perspectives of breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1921–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1031-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redaelli A, Stephens JM, Brandt S, et al. Short- and long-term effects of acute myeloid leukemia on patient health-related quality of life. Cancer Treat Rev. 2004;30(1):103–17. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(03)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towsley GL, Beck SL, Watkins JF. “Learning to live with it”: Coping with the transition to cancer survivorship in older adults. J Aging Stud. 2007;21(2):93–106. [Google Scholar]