Abstract

The role of mammalian skin in harbouring and transmitting arthropod-borne protozoan parasites has been overlooked for decades as these pathogens have been regarded primarily as blood-dwelling organisms. Intriguingly, infections with low or undetected blood parasites are common, particularly in the case of Human African Trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. We hypothesise, therefore, the skin represents an anatomic reservoir of infection. Here we definitively show that substantial quantities of trypanosomes exist within the skin following experimental infection, which can be transmitted to the tsetse vector, even in the absence of detectable parasitaemia. Importantly, we demonstrate the presence of extravascular parasites in human skin biopsies from undiagnosed individuals. The identification of this novel reservoir requires a re-evaluation of current diagnostic methods and control policies. More broadly, our results indicate that transmission is a key evolutionary force driving parasite extravasation that could further result in tissue invasion-dependent pathology.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.17716.001

Research Organism: Human, Mouse, Other

Introduction

Understanding the process of parasite transmission is essential for the design of rational control measures to break the disease cycle and requires the identification of all reservoirs of infection. In a number of vector-borne diseases, it is becoming evident that asymptomatic individuals, be they humans or animals, can represent a significant proportion of the infected population and therefore an important reservoir of disease that requires targeting by control measures (Lindblade et al., 2014; Fakhar, 2013; Koffi et al., 2006; Berthier et al., 2016). The recent identification in West Africa of asymptomatic individuals with human trypanosomiasis (long-term seropositives) but undetected parasitaemia, raises the question of what role these individuals play in disease transmission (Koffi et al., 2006; Jamonneau et al., 2012; Bucheton et al., 2011; Kanmogne et al., 1996). Therapy is currently only directed towards microscopy-positive individuals and thus a proportion of the infected population remain untreated.

There is convincing evidence that seropositive individuals with low or undetected parasitaemia contain transmissible trypanosomes. Xenodiagnosis experiments, in which tsetse flies are fed on microscopy-negative infected humans (Frezil, 1971) or, more recently, experimentally-infected pigs (Wombou Toukam et al., 2011), have shown that these apparently aparasitaemic hosts contain the parasite since the tsetse flies became infected. It is uncertain where the trypanosomes reside in the host but, given the telmophagus (slash and suck) feeding habit of the tsetse fly, they could be skin-dwelling parasites ingested with the blood meal. Our findings suggest that parasites may be sufficiently abundant in the skin to allow transmission and therefore the skin may represent an anatomical reservoir of infection.

Detection of trypanosomes in the skin is not well documented, although there are descriptions of cutaneous symptoms associated with African trypanosomiasis and distinct ‘trypanid’ skin lesions (McGovern et al., 1995). Imaging data from mouse models of infection suggest that trypanosomes sequester to major organs such as the spleen, liver and brain (Blum et al., 2008; Kennedy, 2004) and recent evidence has demonstrated trypanosomes in extravascular adipose tissue (Trindade et al., 2016). These adipose-associated trypanosomes appear to be a new life-cycle stage with a distinct transcriptional profile and, while tsetse bite-site associated transmission has been suggested (Caljon et al., 2016), and a historical study made a passing observation of localised deposition of trypanosomes in the skin matrix (Goodwin, 1971), the broader role of skin-dwelling trypanosomes in transmission remains unclear. In this paper we report the investigation of a possible anatomical reservoir in the skin of the mammalian host. We provide conclusive evidence of T.b. brucei, (a causative agent of animal trypanosomiasis) and the human-infective trypanosome, T.b. gambiense, invading the extravascular tissue of the skin (including but not restricted to the adipose tissue) and undergoing onward transmission despite undetected vascular parasitaemia. We also provide evidence of localisation of trypanosomes within the skin of undiagnosed humans. The presence of a significant transmissible population of T. brucei in this anatomical compartment is likely to impact future control and elimination strategies for both animal and human trypanosomiases.

Results

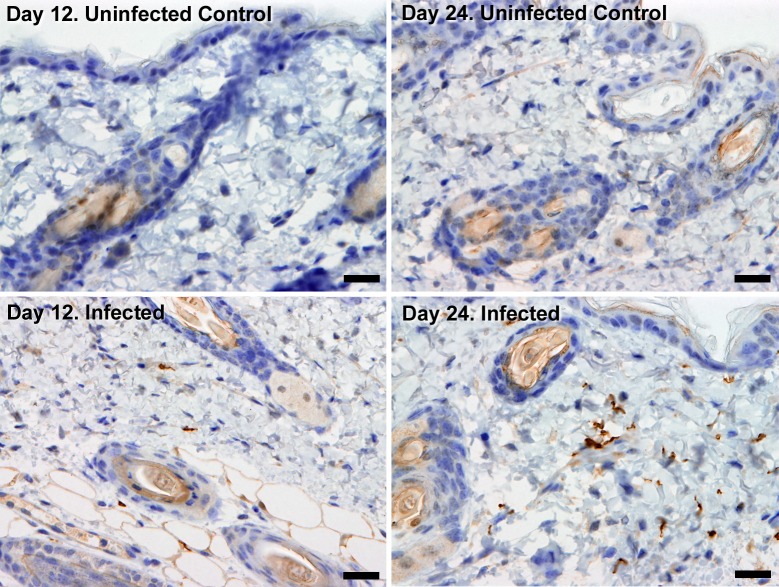

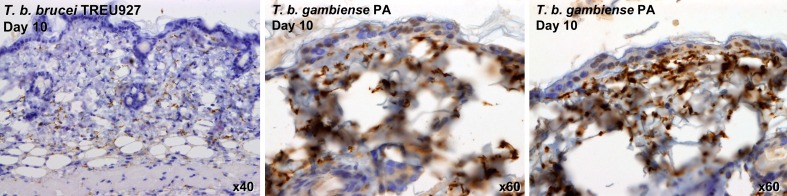

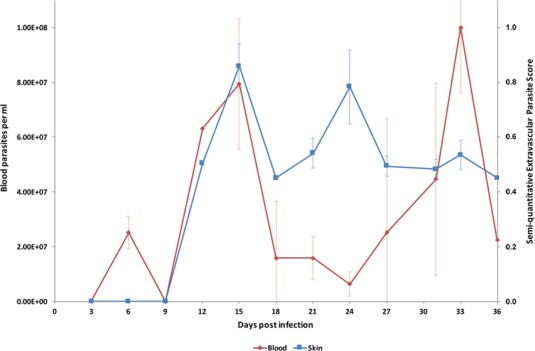

In order to investigate the potential for extravascular skin invasion by T. brucei, BALB/c mice were inoculated via IP injection with the low virulence STIB247 strain of T. brucei and skin sections were assessed over a 36-day time-course. The presence and relative quantities of extravascular parasites were evaluated by semi-quantitative scoring of the histological samples (Figure 1—source data 1) and compared to blood parasitaemia (Figure 1—source data 2). Extravascular parasites were first observed in the skin 12 days post-infection and remained throughout the experiment. Skin parasite numbers fluctuated to a lesser extent than blood parasitaemia and the apparent periodicity in the skin may be due to one particularly high data point on day 24 (Figure 1). Parasites were found in the dermis, subcutaneous adipose tissue (Figure 2) and in fascia beneath the panniculus carnosus muscle. We did not detect any particular clustering around dermal adipocytes. The presence of parasites in the skin was not associated with major inflammation (Supplementary file 1). To confirm that skin invasion by this parasite was not strain or sub-species specific, the more virulent TREU927 strain of T. brucei and the human-infective T.b. gambiense strain, PA, were used to infect mice. Extravascular skin invasion of the dermis, subcutaneous adipose tissue and fascial planes (Figure 2—figure supplement 1) was evident with associated mild to moderate inflammation (Supplementary file 2), in some instances the degree of skin invasion in the T.b. gambiense infected mice was far greater than T.b. brucei, perhaps suggesting a greater propensity for sequestration in this sub-species.

Figure 1. Parasite densities in the blood and in the extravascular tissue of the skin over a time-course.

The blood parasitaemia of T.b. brucei strain STIB247 (red) and the semi-quantitative score of extravascular parasites in the skin (blue) are shown over a 36-day time-course following infection in Balb/C mice. Blood parasitaemia was measured using phase microscopy using methodology outlined in (Lumsden, 1963). Skin parasite burden is an average of five high-power fields scored by histological analysis (0 = no parasites detectable; 1 = low numbers of parasites; 2 = moderate numbers of parasites; 3 = large numbers of parasites). Standard error shown (n = 3).

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.17716.002

Figure 2. Extravascular localisation of trypanosomes during an infection.

Histological sections of dorsal skin from uninfected and infected Balb/C mice stained with trypanosome-specific anti-ISG65 antibody (brown), counterstained with Gill’s Haematoxylin stain (blue) at 12 days and 24 days post-inoculation with T.b. brucei strain STIB247. Parasites are visible in extravascular locations of the skin including the deep dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissue from day 12. The scale bar represents 20 µm.

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Skin invasion by T.b. brucei strain TREU927 and T.b. gambiense strain PA.

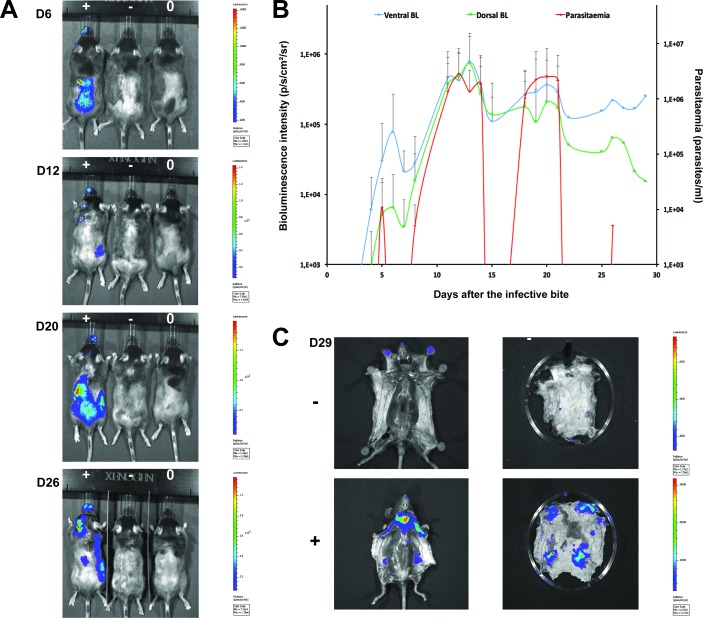

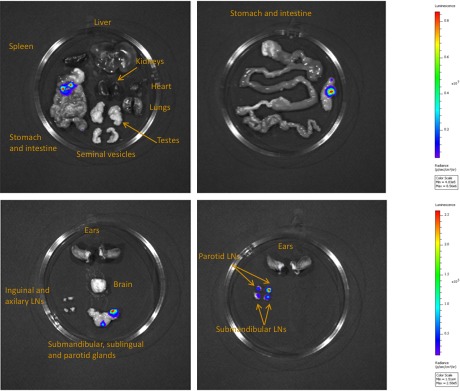

To confirm that the extravascular distribution of parasites was not an artefact of the route of inoculation, infections by natural vector transmission were carried out using a bioluminescent T.b. brucei strain, AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato. Mice were infected by a single infective bite of an individual G.m. morsitans. After 4 to 11 days and up to the end of the experiment, parasites were observed in the skin with a dynamic distribution (Figure 3A) and a variable density (Figure 3B). Parasites were first detected in the blood between 5 and 19 days after natural transmission and parasitaemia remained lower than 10 (Kanmogne et al., 1996) parasites/ml. Observed bioluminescence directly reflects the total number of living parasites in the entire organism, including blood and viscera, but the intensity of the signal decreases with tissue depth. Therefore, at the end of each experiment, mice were sacrificed and their organs were checked for bioluminescence. The presence of extravascular parasites in cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues was first demonstrated by bioluminescence imaging in entire dissected skins (Figure 3C) and was not necessarily localised to the bite site. In addition to the skin, only the spleen, some lymph nodes and adipose tissue were observed to be positive for bioluminescence in several individuals (Figure 3—figure supplement 1). This suggests that the observed bioluminescence is likely to originate predominantly, but not solely, from parasites in the skin. In addition, only mild inflammation was observed after 29 days (Figure 3—figure supplement 2).

Figure 3. Dynamics of parasite distribution in the extravascular tissue of the skin and in the blood during a representative course of infection following natural transmission.

A total of seven mice were infected by the single infective bite of an individual G.m. morsitans on the belly with the T.b. brucei AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato strain. Panels A and C depict representative patterns. (A) Examples of bioluminescence profiles of 3 mice (+ bitten by an infected fly, - bitten by an uninfected fly and 0 not bitten) 6, 12, 20 and 26 days after the bite are shown. (B) Ventral (blue) and dorsal (green) bioluminescence (BL) intensities (in p/s/cm2/sr on the left Y-axis) and parasitaemia (in parasites/ml in red on the right Y-axis) were measured daily for 29 days and plotted as mean ± SD (n = 7 mice). (C) The entire skins of mice (+) and (-) were dissected for bioluminescence imaging 29 days after the bite. For the mouse (+), Figure 3—figure supplement 1 shows the bioluminescence profile of dissected organs, Figure 3—figure supplement 2 presents the skin inflammation, and Figure 3—figure supplement 3 shows labelled parasites in skin sections.

Figure 3—figure supplement 1. Bioluminescence mostly originates from parasites in the skin.

Figure 3—figure supplement 2. Mild inflammation of skin tissues one month after an infection by natural transmission.

Figure 3—figure supplement 3. Extravascular parasites in the skin express both VSGs and PAD1 surface markers.

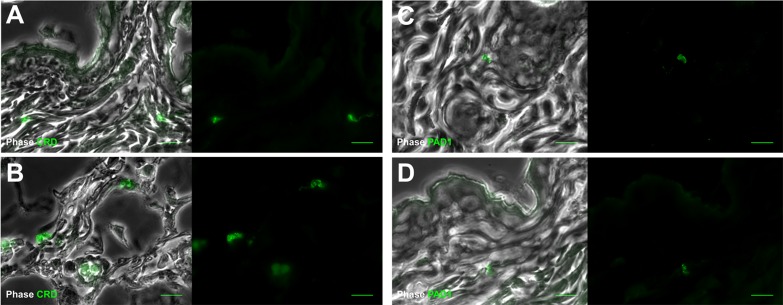

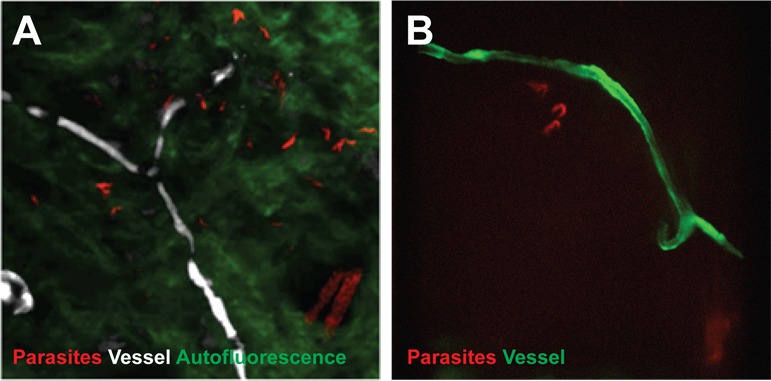

To confirm that trypanosomes in the skin are a viable population, fluorescent parasites were monitored by two intravital imaging methods following IP injection and natural transmission (Figure 4). First, IP-injected fluorescent T. brucei STIB247 were imaged in vivo using 2-photon microscopy (Figure 4A). Extravascular trypanosomes observed in the dermal layer of dorsal skin were highly motile, consistent with viability (Video 1). Second, naturally-transmitted fluorescent T. brucei AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato were imaged in vivo using spinning-disk confocal microscopy in the C57BL/6J-Flk1-EGFP mouse line that has green fluorescent endothelial cells in the lymphatic and blood vessels (Ema et al., 2006) (Figure 4B). Extravascular trypanosomes were observed in the dermal layer of the ear and were highly motile (Videos 2, 3 and 4).

Video 1. Extravascular trypanosomes visualised in the skin using 2-photon microscopy.

Intravital multi-photon imaging of the flank skin during trypanosome infection 10 days after IP inoculation. An intravenous injection of non-targeted quantum dots prior to imaging allowed visualisation of blood vessels. mCherry STIB247 T.b. brucei parasites (red) are observed moving in the extravascular region surrounding blood vessels of the dermis (white). Collagen auto-fluorescence is visible as green.

Video 2. Extravascular trypanosomes visualised in the skin using spinning-disk confocal microscopy.

Spinning-disk confocal live imaging of the ear of anKdr (Flk1) C57BL/6J Rj mouse during a trypanosome infection after natural transmission. T.b. brucei AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato parasites expressing tdTomato (red) are observed moving in the extravascular region surrounding blood and / or lymphatic vessels of the dermis (green).

Video 3. Extravascular trypanosomes visualised in the skin using spinning-disk confocal microscopy.

Video 4. Extravascular trypanosomes visualised in the skin using spinning-disk confocal microscopy.

Figure 4. Extravascular localisation of trypanosomes during an infection visualised using multi-photon microscopy (A) and spinning-disk confocal microscopy (B).

(A) Still-image extracted from video (Video 1) of multi-photon live imaging of dorsal skin during a trypanosome infection. Intravenous non-targeted quantum dots (white) highlight blood vessels. T.b. brucei STIB 247 parasites transfected with mCherry to aid visualisation (red) are clearly visible and motile outside the vasculature and within the extravascular skin matrix (green). (B) Still-image extracted from (Video 3) of spinning-disk confocal live imaging of the ear of an Kdr (Flk1) C57BL/6J Rj mouse during a trypanosome infection. T.b. brucei AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato parasites expressing tdTomato (red) are moving in the extravascular region surrounding a vessel of the dermis (green).

Differentiation of dividing trypanosomes to non-dividing stumpy forms is essential for transmission to the tsetse. Using the relative transcript abundance of the stumpy marker Protein Associated with Differentiation 1 (PAD1) (Dean et al., 2009) to an endogenous control, Zinc Finger Protein 3 (ZFP3) (Walrad et al., 2009), we estimated that approximately 20% of skin-dwelling parasites were stumpy (Supplementary file 3). To directly determine the proportion of stumpy forms in skin sections, histological staining for PAD1 was also performed (Table 1—source data 4). PAD1-positive cells were observed in variable proportions (from 8 to 80%) in all bioluminescent skin samples examined after IP injection (Supplementary file 4). Following natural transmission, up to 38% of parasites detected using VSG surface markers (Figure 3—figure supplement 3A–B) also expressed PAD1 (Figure 3—figure supplement 3C–D) (n = 441 cells from 8 skin sections). In all skin sections, stumpy parasites were homogenously distributed in the dermis and subcutaneous adipose tissues.

We next assessed the ability of skin-dwelling parasites to infect tsetse flies. Teneral flies (immature flies that have not yet taken a blood meal) were fed on different regions of skin from mice infected with AnTat1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato with differing levels of bioluminescence across the skin (Table 1—source data 1 and Table 1—source data 2). This was repeated in 20 mice with differing levels of parasitaemia. Flies were dissected and checked for the presence of fluorescent trypanosomes after two days (Table 1). In mice with undetectable or low parasitaemia (<5 × 104 parasites/ml), no parasites were found in flies fed on non-bioluminescent regions. Conversely, a median of 36% (± 23%, n = 70) of flies that fed on bioluminescent regions of low parasitaemic mice became infected (Table 1 and Table 1—source data 3). This demonstrates that skin parasites, from mice without visible parasitaemia, can contribute to tsetse infection, possibly reflecting human asymptomatic infections. When parasites were detected in the blood and skin, tsetse infection rates increased up to 100% (median of 61% ± 22%, n = 120) (Table 1 and Table 1—source data 3). Parasites taken-up from the skin were able to further develop through the life-cycle to early procyclic forms in the fly as evidenced by GPEET-procyclin marker on the parasites surface (n = 721 cells from 16 flies) (Table 1—source data 4 and Supplementary file 4).

Table 1.

Skin parasites are ingested during tsetse pool-feeding. Mice were IP infected with T.b. brucei AnTat1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato and the parasitaemia and bioluminescence were monitored daily until the day of xenodiagnosis. The number of parasites in the blood was determined using a haemocytometer or a flux cytometer. The number of parasites in the skin was estimated from the measured bioluminescence intensity by using a standard curve (Table 1—source data 1 and Table 1—source data 2). Batches of teneral flies were fed on different skin regions of mice infected with differing levels of bioluminescence across the skin and with differing levels of parasitaemia (Table 1—source data 2 and Table 1—source data 3). Fly batches A4A, A2A, B1A, 3B and 3A were used to assess tsetse transmission in hosts with low numbers of blood parasites but high numbers skin parasites, while fly batches 1B, 1A, 4B, 4A, 2B, 2A, B2B and B4A were used to investigate the impact of high numbers of parasites in both the skin and blood. Flies were dissected and their midguts checked for the presence of fluorescent trypanosomes after two days to determine the proportion of infected flies (Table 1—source data 4A–B). For some of these experiments, results of an in-depth quantification of parasite stages by IFA is provided in Supplementary file 4. Stumpy forms were observed only in the blood of mice with parasitaemia values highlighted in purple. Bioluminescence was detected in the skin of mice with values highlighted in grey.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7554/eLife.17716.016

| Fly batches | Parasites in blood (per ml) | Parasites in skin (per cm2) | Dissected flies | Fly infection rates (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 0% |

| C | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0% |

| A4B | < 104 | < 103 | 16 | 0% |

| B1B | 2.2 × 104 | < 103 | 13 | 0% |

| A4A | < 104 | 6.6 × 105 | 17 | 35% |

| A2A | 1.1 × 104 | 3.8 × 106 | 7 | 86% |

| B1A | 2.2 × 104 | 4.6 × 107 | 16 | 31% |

| 3B | 4.4 × 104 | 2.6 × 104 | 14 | 36% |

| 3A | 4.4 × 104 | 2.6 × 104 | 16 | 38% |

| 1B | 1.8 × 105 | 8.0 × 103 | 12 | 67% |

| 1A | 1.8 × 105 | 8.0 × 103 | 14 | 79% |

| 4B | 2.2 × 105 | 1.2 × 104 | 17 | 53% |

| 4A | 2.2 × 105 | 1.2 × 104 | 18 | 56% |

| 2B | 1.6 × 106 | 8.0 × 103 | 14 | 36% |

| 2A | 1.6 × 106 | 3.2 × 104 | 18 | 39% |

| B4B | 4.3 × 106 | 6.7 × 107 | 10 | 80% |

| B4A | 4.3 × 106 | 6.7 × 107 | 17 | 100% |

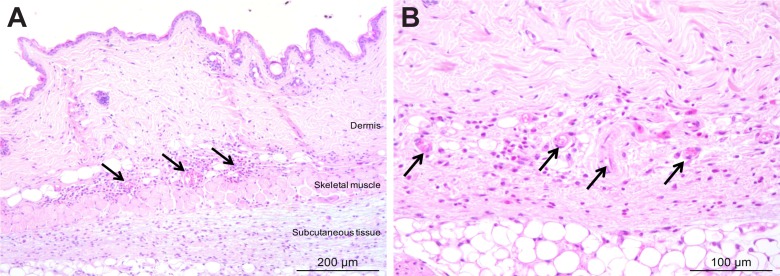

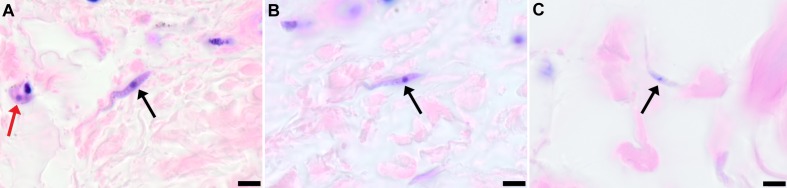

To demonstrate that skin invasion by trypanosomes can occur in humans as well as the murine model, slides of historical skin biopsies, taken as part of a diagnostic screening programme for Onchocerca microfilaria in the trypanosomiasis-endemic Democratic Republic of the Congo, were examined for trypanosomes. At the time of sampling, the incidence of trypanosomiasis was 1.5–2% and we hypothesised that some individuals may have harboured undiagnosed infections. Re-examination of 1121 skin biopsies by microscopy revealed six individuals with trypanosomes in their skin (Figure 5). These individuals had not previously been diagnosed with human trypanosomiasis by clinical signs or the presence of blood parasites.

Figure 5. Extravascular localisation of trypanosomes in previously unidentified human cases of trypanosomiasis.

Histological sections of skin collected from previously unidentified cases of human trypanosomiasis from the Democratic Republic of Congo, showing the presence of extravascular parasites in biopsies from three individuals (A, B and C). Skin biopsies were collected as part of a national onchocerciasis screening programme that took place in the same geographic region as an active trypanosomiasis focus. Slides were stained with Giemsa and examined under oil immersion at 100x magnification. In addition to visible slender forms (black arrows) in the extravascular tissue of the skin, a clearly identifiable stumpy transmission form with typical morphology and an unattached undulating membrane is also present in the skin of one individual (red arrow in A). The scale bar represents 5 µm.

Discussion

We have shown that there exists a significant yet overlooked population of live, motile, extravascular T. brucei in the dermis and subcutis of animal models infected by artificial routes or by vector transmission. It is likely that once injected the parasites disseminate via the lymph and blood to the skin where they are ingested during tsetse fly pool-feeding and readily initiate cyclical development in the vector. Given the relative volume of the skin organ compared to the vasculature, it is possible, depending on the density of skin invasion, that more parasites exist in the skin than in the blood. The skin, therefore, represents an unappreciated reservoir of infection. The extravasation of trypanosomes was described previously in major organs such as liver, spleen (Blum et al., 2008; Kennedy, 2004) and visceral adipose tissue (Trindade et al., 2016), but the importance of these parasites in transmission was not investigated. Here we show that these skin-dwelling trypanosomes contribute to transmission and could explain the maintenance of disease foci, despite active screening and treatment. Skin invasion for enhanced transmission is likely a powerful evolutionary force driving extravasation, suggesting that the generalised tissue penetration underlying pathogenesis (i.e. splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, CNS invasion) is a secondary epiphenomenon. A skin reservoir also presents a novel target for diagnostics (e.g. skin biopsies), allowing the prevalence of infection to be accurately determined and the identification of any previously undetected animal reservoirs of human disease.

The skin as an anatomical reservoir of parasites is a recurring theme in arthropod-borne human diseases such as Leishmania (Sacks, 2008; Schlein, 1993) and Onchocerca (Symptomatology, 1974; Dalmat, 1955). Here we present evidence of trypanosomes in the skin of hitherto undiagnosed individuals. This anatomical reservoir may serve to explain how HAT foci re-emerge and persist despite low numbers of reported cases even in the absence of an animal reservoir (Kagbadouno et al., 2012; Cordon-Obras et al., 2009; Balyeidhusa et al., 2012).

HAT was once widespread across much of sub-Saharan Africa but concerted control efforts brought it close to elimination during the 1960s (World Health Organization 2000, 2013). However, disease foci persisted, with a resurgence in the number of reported cases to over 300,000 in the 1990s (World Health Organization 2000; Steverding, 2008). Currently, HAT is approaching elimination in many areas (World Health Organization 2013; Simarro et al., 2012). Understanding how HAT evaded elimination in the latter half of the 20th century and how it continues to persist is vital to efforts to eliminate the disease. For example, our results indicate that it may be necessary to develop novel therapeutics capable of accessing extravascular compartments. The current policy in most endemic countries is not to treat serologically positive individuals unless they demonstrate active infection, due to the long duration and high toxicity of treatment and the low predictive value of the serological tests. We suggest that this policy should be reconsidered in light of our compelling evidence that they represent a carrier population which may maintain HAT foci and explain previously thwarted efforts to eliminate this major pathogen.

Materials and methods

Trypanosome strains and cultures

All strains used in this study are pleomorphic. STIB247 is a low virulence T.b. brucei strain that induces a chronic infection and was isolated from a hartebeest in the Serengeti in 1971 (Geigy et al., 1973). TREU927 is the genome reference strain for T. brucei and is more virulent than STIB247. This strain was isolated from a tsetse fly in Kenya in 1969/1970 (Goedbloed et al., 1973). PA is a human-infective group 1 T.b. gambiense strain isolated from a patient in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1975 (Tait et al., 1984). mCherry STIB247 was created by transfection of STIB247 with pHD1034-mCherry (Myburgh et al., 2013). This strain constitutively expresses fluorescent mCherry from the ribosomal RNA promoter and its expression is stable over repeated passage.

The AnTat 1.1E clone of T.b. brucei was derived from a strain originally isolated from a bushbuck in Uganda in 1966 (Le Ray et al., 1977). Bloodstream forms were cultivated in HMI11 medium supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum at 37°C in 5% CO2. This strain was genetically engineered to produce two strains continuously expressing the red-shifted luciferase (PpyRE9H) and the tdTomato red fluorescent protein either individually or in combination.

For the first AnTat 1.1E strain, the pTbAMLuc plasmid (M. Taylor, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK) was used for continuous cytosolic expression of the red-shifted luciferase PpyRE9H. The tdTomato coding sequence was cloned with HindIII and BamHI into the pTSARib vector (Xong et al., 1998), generating the final pTSARib-tdTomato construct. The two plasmids were linearised with KpnI and SphI restriction enzymes, respectively, and used to transform procyclic parasites with an Amaxa Nucleofector (Lonza) (Burkard et al., 2007). After 24 hr, transfected cells were selected by the addition of blasticidin or puromycin (10 μg/ml). After one week, the population was examined (i) for red fluorescence by fluorescence microscopy and (ii) for both red fluorescence and bioluminescence by using a fluorimeter Infinite 200 (Tecan, Switzerland). Cells were sub-cloned by limiting dilution, and clone selection was performed after 15 days by measuring both bioluminescence in a microplate reader Infinite 200 (Tecan) and fluorescence with a Muse cell Analyzer (Merck-Millipore). This strain, named AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato, was used for natural transmission experiments.

The second AnTat 1.1E strain expressing the 3.1 Kb chimeric multiplex reporter protein PpyRE9H::TY1::tdTomato was named AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato. This cytoplasmic reporter is composed of three distinct markers: the red-shifted luciferase (PpyRE9H) is fused to the tdTomato red fluorescent protein by a TY1 tag. Briefly, the 1.68 Kb optimised version of the North American firefly Photinus pyralis luciferase (Branchini et al., 2005) was fused with a 10-bp sequence known as TY1-tag (Bastin et al., 1996) and cloned into the pTSARib plasmid (Xong et al., 1998) by using XhoI and HindIII restriction enzymes to obtain the pTSARib-PpyRE9H-TY1 plasmid. Finally, the 1.4 Kb coding region of the tdTomato fluorescent protein was inserted downstream using HindIII and BamHI. The resulting 8.9 Kb vector, containing a blasticidin S resistance cassette, was linearised with SphI to integrate the rDNA promoter locus. Bloodstream parasites were transformed with an Amaxa Nucleofector (Lonza) (Burkard et al., 2007), sub-cloned by limiting dilution, and clone selection was performed by measuring both bioluminescence in a microplate reader Infinite 200 (Tecan) and fluorescence with a Muse cell Analyzer (Merck-Millipore). The selected AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato sub-clone was comparable to the parental wild-type strain in terms of growth rate (Table 1—source data 1A), pleomorphism (Table 1—source data 4C), tsetse infectivity and virulence in mice (Table 1—source data 2). In order to verify the reliability of the bioluminescent marker as well as to define the bioluminescence detection threshold of the AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato selected sub-clone, a parasite density / bioluminescence intensity analysis was performed in 96-micro-well plates with an IVIS Spectrum imager (Perkin Elmer). Parasite density and bioluminescence intensity were correlated when bioluminescence levels were higher than 104 p/s/cm²/sr, corresponding to about 103 parasites, allowing estimation of the parasite density from in vivo imaging over this threshold (Table 1—source data 1B). This correlation was verified by quantification in a microplate reader Infinite 200 (Tecan) at the very beginning of the first in vivo experiment as well as the end of the last one, demonstrating the stability of the triple reporter expression in the AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato selected sub-clone over time, especially after at least one full in vivo parasite cycle in the tsetse fly and the mammalian host (Table 1—source data 1C). This strain was used for xenodiagnosis experiments and quantification of parasite densities.

Mouse strains

BALB/c and C57BL/6J mice were used as models for chronic disease (Magez and Caljon, 2011). In addition, to allow for further 3D intravital imaging of the lymphatic and blood systems, C57BL/6J-Flk1-EGFP mice expressing a GFP tagged Kdr (Flk1) gene encoding the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR-2) were used (Ema et al., 2006).

Ethical statements

This study was conducted under Home Office and SAPO regulations in the UK and in strict accordance with the recommendations from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the European Union (European Directive 2010/63/UE) and the French Government. The protocol was approved by the 'Comité d’éthique en expérimentation animale de l’Institut Pasteur' CETEA 89 (Permit number: 2012–0043 and 2016–0017) and undertaken in compliance with Institut Pasteur Biosafety Committee (protocol CHSCT 12.131).

Skin invasion time-course

A total of 36 eight-week old BALB/c mice (Harlan, UK) were inoculated by intra-peritoneal (IP) injection with 104 parasites of strain STIB 247. Parasitaemia was assayed on each subsequent day using phase microscopy (Lumsden, 1963). Twenty-four uninfected animals served as controls. Every three days for 36 days, three infected animals and two uninfected animals were culled and 2 cm2 skin samples removed from the dorsum. Skin samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin prior to histological analysis.

Natural infections using tsetse flies

Tsetse flies (Glossina morsitans morsitans) were maintained, infected and dissected at the Institut Pasteur as described previously (Rotureau et al., 2012). Flies were infected with AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato parasites. Positive flies were selected first by screening the abdominal fluorescence (midgut infection) 15 days after the infective meal, and then by a salivation test (mature salivary gland infection) after one month. Single flies with salivary gland infections were used to infect the abdomen of mice anaesthetised by IP injection of ketamine (Imalgene 1000 at 125 mg/kg) and xylazine (Rompun 2% at 12.5 mg/kg) and feeding was confirmed by visual observation of the fly abdomen full of blood. Control mice were either not bitten or bitten by uninfected flies. The presence and density of parasites in the blood was determined daily by automated fluorescent cell counting with a Muse cytometer (Merck-Milllipore, detection limit 5.102 parasites/ml) or by direct examination under a phase microscope with standardised one-use haemocytometers (Hycor Kova, detection limit 104 parasites/ml), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Infection for xenodiagnosis

A total of 20 seven-week-old male C57BL/6J Rj mice (Janvier, France) were IP injected with 10 (Jamonneau et al., 2012) AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato bloodstream forms. Parasitaemia was assayed daily by automated fluorescent cell counting with a Muse cytometer (Merck-Millipore, detection limit 5.102 parasites/ml) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

PAD1/ZFP3 relative expression

Three BALB/c were infected with T.b. brucei strain TREU927 and culled at day 11. The mice were perfused and a 2 cm2 region of skin removed from the flank. Skin sections were lysed using a Qiagen Tissuelyzer LT and RNA extracted using a Qiagen RNAeasy kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. 100 ng of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed using an Invitrogen Superscript III RT kit. qPCR was performed on each sample using 5 µl of cDNA using a protocol and primers validated previously (MacGregor et al., 2011) on an Agilent Technologies Stratagene Mx3005P qPCR machine. The ratio of PAD1 to ZFP3, and hence the proportion of cells transcribing the PAD1 gene, was estimated using the Agilent Technologies MXPro software.

Xenodiagnosis

Mice were first anaesthetised by IP injection of ketamine (Imalgene 1000 at 125 mg/kg) and xylazine (Rompun 2% at 12.5 mg/kg). Batches of 10 teneral male tsetse flies (from 8 to 24 hr post-eclosion) were then placed in 50 ml Falcon tubes closed with a piece of net through which they were allowed to feed directly on mouse skin regions of interest for 10 min. The selection of the skin regions for fly feeding was based on mice bioluminescence profiles and parasitaemia. Unfed flies were discarded and fed flies were maintained as previously described. Anaesthetised mice were finally sacrificed by cervical dislocation and their skin was dissected for controlling bioluminescence with an IVIS Spectrum imager (Perkin Elmer). All the flies were dissected and checked for the presence of trypanosomes either 2 or 14 days after their meal on mouse skin by two entomologists blinded to group assignment and experimental procedures. Dissections were performed as previously described (Rotureau et al., 2012), entire midguts were scrutinised by fluorescence microscopy to detect and count living red fluorescent parasites, and positive midguts were further treated for IFA. A total of 420 flies were used in 3 independent xenodiagnosis experiments.

In vitro bioluminescence imaging

To perform the parasite density / bioluminescence intensity assay with AnTat 1.1E AMLuc/TY1/tdTomato bloodstream forms, parasites were counted, centrifuged and resuspended in fresh HMI11 medium at 10.106 cells/ml. Then, 100 μl (or 106 parasites) of this suspension were transferred into black clear-bottom 96-well plates and serial 2-fold dilutions were performed in triplicate adjusting the final volume to 200 μl of HMI11 with 300 μg/ml of beetle luciferin (Promega, France). Luciferase activity was quantified after 10 min of incubation with a microplate reader Infinite 200 (Tecan), following the instructions of the Promega Luciferase Assay System. After background removal, results were analysed as mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

In vivo bioluminescence imaging

Infection with bioluminescent parasites was monitored daily by detecting the bioluminescence in whole animals with the IVIS Spectrum imager (Perkin Elmer). The equipment consists of a cooled charge-coupled camera mounted on a light-tight chamber with a nose cone delivery device to keep the mice anaesthetised during image acquisition with 1.5% isofluorane. D-luciferin potassium salt (Promega) stock solution was prepared in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at 33.33 mg/ml, filter-sterilised and stored in a −20°C freezer. To produce bioluminescence, mice were inoculated IP with 150 μl of D-luciferin stock solution (250 mg/kg). After 10 min of incubation to allow substrate dissemination, all mice were anaesthetised in an oxygen-rich induction chamber with 2% isofluorane, and images were acquired by using automatic exposure (30 s to 5 min) depending on signal intensity. Images were analysed with Living Image software version 4.3.1 (Perkin Elmer). Data were expressed in average radiance (p/s/cm²/sr) corresponding to the total flux of bioluminescent signal according to the selected area (total body of the mouse here). The background noise was removed by subtracting the bioluminescent signal of the control mouse from the infected ones for each acquisition.

2-photon microscopy

Intravital multi-photon microscopy studies were carried out using a Zeiss LSM7 MP system equipped with a tuneable titanium:sapphire solid-state two-photon excitation source (4W, Chameleon Ultra II, Coherent Laser Group) coupled to an Optical Parametric Oscillator (Chameleon Compact OPO; Coherent). Movies were acquired for 10 to 15 min with an X:Y pixel resolution of 512 × 512 in 2 μm Z increments producing up to 40 μm stacks. 3D tracking was performed using Volocity 6.1.1 (Perkin Elmer, Cambridge, UK). Values representing the mean velocity, displacement and meandering index were calculated for each object. Mice were anaesthetised IP using medetomidine (Domitor 0.5 mg/kg) and ketamine (50 mg/kg) and placed on a heated stage. Following removal of hair with a depilatory cream, dorsal skin was imaged. An intravenous injection of non-targeted quantum dots (Qdot705) (Life Technologies, UK) prior to imaging allowed visualisation of blood vessels.

Spinning-disk confocal microscopy

AnTat1.1E AMLuc/tdTomato parasites were monitored in the ear of Kdr (Flk1) C57BL/6J Rj mice by spinning-disk confocal microscopy as described previously (Rotureau et al., 2012). Briefly, mice were first anaesthetised by IP injection of ketamine (Imalgene 1000 at 125 mg/kg) and xylazine (Rompun 2% at 12.5 mg/kg). Mice were wrapped in a heating blanket and placed on an aluminium platform with a central round opening of 21 mm in diameter. A coverslip was taped on the central hole and the mouse was positioned so that the ear was lying on this oiled coverslip. Imaging was performed using an UltraView ERS spinning-disk confocal system (Perkin Elmer) with a x40 oil objective (1.3 numerical aperture). Movies were acquired by an EM-CCD camera (Hamamatsu) controlled by the Volocity software (Perkin Elmer) with an exposure time of 500 ms for a total of 30 to 120 s. Images were analysed using ImageJ 1.48v and its plugin Bio-formats importer (NIH).

Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of the skin

Paraformaldehyde-fixed skin samples were trimmed and processed into paraffin blocks. Sections were stained with Haematoxylin and Eosin (HE). Additional serial sections were processed for immunohistochemical staining using a polyclonal rabbit antibody raised against the invariant surface glycoprotein 65 (IGS65) (M. Carrington, Cambridge, UK) using a Dako Autostainer Link 48 (Dako, Denmark) and were subsequently counterstained with Gill’s Haematoxylin.

Histopathological assessment of inflammation in the skin

The extent of cutaneous inflammatory cell infiltration was assessed in haematoxylin and eosin stained sections with a semi-quantitative scoring system applied by two pathologists blinded to group assignment and experimental procedures. The extent of mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in the dermis and/or subcutis was assessed on a 0 to 3 grading scale (0 = no inflammation or only few scattered leukocytes; 1 = low numbers of inflammatory cells; 2 = moderate numbers of inflammatory cells; 3 = large numbers of inflammatory cells). Ten high-power fields were scored for each skin sample. An inflammation score calculated as the average of the scores in the 10 high-power fields was determined for each sample.

Semi-quantitative evaluation of the parasite burden in skin sections

Parasite burden was assessed in skin sections stained with anti-IGS65 antibody by two pathologists blinded to group assignment and experimental procedures. Presence of parasites defined as intravascular (parasites within the lumen of dermal or subcutaneous small to medium-sized vessels) and extravascular (parasites located outside blood vessels, scattered in the connective tissue of the dermis or in the subcutis) was evaluated in 5 randomly selected high-power fields at x40 magnification with a 0 to 3 semi-quantitative grading scale (0 = no parasites detectable; 1 = low numbers of parasites (<20); 2 = moderate numbers of parasites (20 < 50); 3 = large numbers of parasites (>50). An average parasite burden score was calculated for each sample.

Immunofluorescence analysis

Cells were treated for immunofluorescence after paraformaldehyde or methanol fixation as described previously (Dean et al., 2009). Parasites were stained with one or two of the following antibodies: (i) the anti-CRD polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:300) to label the cross-reactive determinant of the glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors of proteins, predominantly the variant surface glycoproteins (Zamze et al., 1988), (ii) the anti-PAD1 polyclonal rabbit antibody (1:100) targeting the carboxylate-transporter Proteins Associated with Differentiation 1 (PAD1) (Keith Matthews, Edinburgh, UK) (Dean et al., 2009), (iii) the anti-GPEET mouse IgG3 monoclonal antibody (1:500) targeting the T. brucei GPEET-rich procyclin (Acris Antibodies GmbH, San Diego, USA), (iv) the L8C4 mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody labelling an epitope of the PFR2 protein (Kohl et al., 1999). Specific antibodies with minimal cross-reactions with mice and coupled to AlexaFluor 488, Cy3 or Cy5 (Jackson ImmunoResearch, USA) were used as secondary antibodies. DNA was stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). IFA image acquisition was carried out on a Leica 4000B microscope with a x100 objective lens using a Hamamatsu ORCA-03G camera controlled by Micro-manager and images were normalised and analysed with ImageJ 1.49v (NIH).

Histopathology of historical human skin samples

Historical human skin samples were collected from 1991 to 1995 as part of The National Onchocerciasis Task Force (NOTF) (Makenga Bof et al., 2015). Of this collection, 1121 paraffin embedded skin samples were cut into 2.5 micron sections and stained with Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). Slides were screened for the presence of parasites by two pathologists independently and representative images taken at x100 magnification.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge P Solano, D Engman, K Matthews, M Taylor, M Carrington, R Amino, E Myburgh and K Gull for providing various material, cell lines, antibodies and plasmids and to A Tait for critically reviewing this manuscript.

Funding Statement

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Funding Information

This paper was supported by the following grants:

Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship (Annette Macleod) - 095201/Z/10/Z to Paul Capewell, Caroline Clucas, William Weir, Anneli Cooper, Annette MacLeod.

Wellcome Trust Wellcome Trust Centre for Molecular Parasitology Core Funding - 085349 to Paul Capewell, Caroline Clucas, William Weir, Anneli Cooper, Annette MacLeod.

Agence Nationale de la Recherche Young Researcher Grant (ANR-14-CE14-0019-01) to Brice Rotureau.

Agence Nationale de la Recherche Post-doctoral fellowship (ANR-14-CE14-0019-01) to Estefania Calvo-Alvarez.

Agence Nationale de la Recherche Investissement d'Avenir programme, Laboratoire d'Excellence (ANR-10-LABX-62-IBEID) to Paul Capewell.

Institut Pasteur to Estefania Calvo-Alvarez, Aline Crouzols, Grégory Jouvion, Brice Rotureau.

Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale to Estefania Calvo-Alvarez, Aline Crouzols, Grégory Jouvion, Brice Rotureau.

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Author contributions

PC, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

CC-T, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

FM, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

PJ, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

CC, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

RAB, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

T-AG, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

EC-A, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

ACr, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

GJ, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

VJ, Acquisition of data.

WW, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

MLS, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

KO, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data.

ACo, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

N-rKS, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

BB, Acquisition of data.

DMN, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

PG, Conception and design.

BR, Conception and design, Acquisition of data, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

AM, Conception and design, Analysis and interpretation of data, Drafting or revising the article.

Ethics

Animal experimentation: This study was conducted and licenced under Home Office and SAPO regulations in the UK and in strict accordance with the recommendations from the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the European Union (European Directive 2010/63/UE) and the French Government. The protocol was approved by the "Comité d'éthique en expérimentation animale de l'Institut Pasteur" CETEA 89 (Permit number: 2012-0043 and 2016-0017) and carried out in compliance with Institut Pasteur Biosafety Committee (protocol CHSCT 12.131).

Additional files

The extent of cutaneous inflammatory cell infiltration during the 36-day STIB247 experiment was assessed on haematoxylin and eosin stained sections with a semi-quantitative scoring system applied by two pathologists blinded to group assignment and experimental procedures.The extent of mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in the dermis and/or subcutis was assessed on a 0 to 3 grading scale (0 = no inflammation or only few scattered leukocytes; 1 = low numbers of inflammatory cells; 2 = moderate numbers of inflammatory cells; 3 = large numbers of inflammatory cells). Ten high-power fields (HPFs) were scored for each skin sample.

The extent of cutaneous inflammatory cell infiltration at day 10 of infection by strain TREU927 experiment was assessed on haematoxylin and eosin stained sections with a semi-quantitative scoring system applied by two pathologists blinded to group assignment and experimental procedures. The extent of mixed inflammatory cell infiltration in the dermis and/or subcutis was assessed on a 0 to 3 grading scale (0 = no inflammation or only few scattered leukocytes; 1 = low numbers of inflammatory cells; 2 = moderate numbers of inflammatory cells; 3 = large numbers of inflammatory cells). Ten high-power fields (HPFs) were scored for each skin sample.

The relative abundance stumpy cells in the skin of three BALB/c was estimated using qPCR at day 11 post-inoculation with T.b. brucei strain TREU927. Mice were culled and perfused to remove blood parasites and a 2 cm (Fakhar, 2013) region of skin removed from the flank. The tissue was homogenised and RNA extracted. 100 ng of RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed and qPCR performed to estimate the cycle thresholds (CT) of the stumpy marker PAD1 and the endogenous control ZFP3. As CT is inversely proportional to amount of target cDNA in the sample and PAD1 and ZFP3 have similar qPCR efficiencies, a comparison of the delta (∆) of CT between PAD1 and ZFP3 transcripts reveals the relative ratio of PAD1 to ZFP3 transcripts and hence the proportion of differentiated parasites transcribing the PAD1 gene.

For some of the xenodiagnosis experiments shown in Table 1, identification and quantification of parasite stages was performed by IFA on blood smears and skin sections.Stumpy forms were observed only in the blood of mice with parasitaemia values highlighted in light grey. Bioluminescence was detected in the skin of mice with values highlighted in dark grey. The number of parasites in the skin was calculated according to the values obtained in the standard in vitro assay (Table 1—source data 1) and is therefore probably an underestimate. Tsetse flies were dissected 2 days after xenodiagnosis. Populations of intermediate and stumpy form cells were assessed in blood smears and in successive skin sections stained either with the anti-CRD antibody or the anti-PAD1 antibody (see Materials and method section). Populations of early procyclic cells were assessed in dissected fly midguts stained with the anti-GPEET antibody (see Materials and method section). ND: not determined.

References

- Balyeidhusa AS, Kironde FA, Enyaru JC. Apparent lack of a domestic animal reservoir in Gambiense sleeping sickness in northwest Uganda. Veterinary Parasitology. 2012;187:157–167. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastin P, Bagherzadeh Z, Matthews KR, Gull K. A novel epitope tag system to study protein targeting and organelle biogenesis in Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1996;77:235–239. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berthier D, Brenière SF, Bras-Gonçalves R, Lemesre JL, Jamonneau V, Solano P, Lejon V, Thévenon S, Bucheton B. Tolerance to Trypanosomatids: A threat, or a key for disease elimination? Trends in Parasitology. 2016;32:157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JA, Zellweger MJ, Burri C, Hatz C. Cardiac involvement in African and American trypanosomiasis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2008;8:631–641. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(08)70230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branchini BR, Southworth TL, Khattak NF, Michelini E, Roda A. Red- and green-emitting firefly luciferase mutants for bioluminescent reporter applications. Analytical Biochemistry. 2005;345:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucheton B, MacLeod A, Jamonneau V. Human host determinants influencing the outcome of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense infections. Parasite Immunology. 2011;33:438–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AA, editor. Onchocerciasis : Symptomatology, Pathology, Diagnosis. Geneva: WHO; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Burkard G, Fragoso CM, Roditi I. Highly efficient stable transformation of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2007;153:220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caljon G, Van Reet N, De Trez C, Vermeersch M, Pérez-Morga D, Van Den Abbeele J. The Dermis as a Delivery Site of Trypanosoma brucei for Tsetse Flies. PLoS Pathogens. 2016;12:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordon-Obras C, Berzosa P, Ndong-Mabale N, Bobuakasi L, Buatiche JN, Ndongo-Asumu P, Benito A, Cano J. Trypanosoma brucei gambiense in domestic livestock of Kogo and Mbini foci (Equatorial Guinea) Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2009;14:535–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalmat HT. The black flies (Diptera, Simuliidae) of Guatemala and their role as vectors of onchocerciasis. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 1955;125:1–425. doi: 10.1093/aibsbulletin/5.5.10-c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean S, Marchetti R, Kirk K, Matthews KR. A surface transporter family conveys the trypanosome differentiation signal. Nature. 2009;459:213–217. doi: 10.1038/nature07997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ema M, Takahashi S, Rossant J. Deletion of the selection cassette, but not cis-acting elements, in targeted Flk1-lacZ allele reveals Flk1 expression in multipotent mesodermal progenitors. Blood. 2006;107:111–117. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhar M, Motazedian MH, Hatam GR, Asgari Q, Kalantari M, Mohebali M. Asymptomatic human carriers of Leishmania infantum : possible reservoirs for Mediterranean visceral leishmaniasis in southern Iran. Annals of Tropical Medicine & Parasitology. 2013;102:577–583. doi: 10.1179/136485908X337526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frezil JL. [Application of xenodiagnosis in the detection of T. gambiense trypanosomiasis in immunologically suspect patients] Bulletin De La SociéTé De Pathologie Exotique Et De Ses Filiales. 1971;64:871–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geigy R, Kauffmann M, Jenni L. Wild mammals as reservoirs for Rhodesian sleeping sickness in the Serengeti, 1970-71. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1973;67:284–286. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(73)90202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goedbloed E, Ligthart GS, Minter DM, Wilson AJ, Dar FK, Paris J. Serological studies of trypanosomiasis in East Africa. II. Comparisons of antigenic types of Trypanosoma brucei subgroup organisms isolated from wild tsetse flies. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 1973;67:31–43. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1973.11686861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin LG. Pathological effects of Trypanosoma brucei on small blood vessels in rabbit ear-chambers. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1971;65:82–88. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(71)90189-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamonneau V, Ilboudo H, Kaboré J, Kaba D, Koffi M, Solano P, Garcia A, Courtin D, Laveissière C, Lingue K, Büscher P, Bucheton B. Untreated human infections by Trypanosoma brucei gambiense are not 100% fatal. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagbadouno MS, Camara M, Rouamba J, Rayaisse JB, Traoré IS, Camara O, Onikoyamou MF, Courtin F, Ravel S, de Meeûs T, Bucheton B, Jamonneau V, Solano P. Epidemiology of sleeping sickness in Boffa (Guinea): where are the trypanosomes? PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanmogne GD, Asonganyi T, Gibson WC. Detection of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense, in serologically positive but aparasitaemic sleeping-sickness suspects in Cameroon, by PCR. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 1996;90:475–483. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1996.11813072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy PG. Human African trypanosomiasis of the CNS: current issues and challenges. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113:496–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI21052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffi M, Solano P, Denizot M, Courtin D, Garcia A, Lejon V, Büscher P, Cuny G, Jamonneau V. Aparasitemic serological suspects in Trypanosoma brucei gambiense human African trypanosomiasis: a potential human reservoir of parasites? Acta Tropica. 2006;98:183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl L, Sherwin T, Gull K. Assembly of the paraflagellar rod and the flagellum attachment zone complex during the Trypanosoma brucei cell cycle. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. 1999;46:105–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1999.tb04592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ray D, Barry JD, Easton C, Vickerman K. First tsetse fly transmission of the "AnTat" serodeme of Trypanosoma brucei. Annales De La SociéTé Belge De MéDecine Tropicale. 1977;57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindblade KA, Steinhardt L, Samuels A, Kachur SP, Slutsker L. The silent threat: asymptomatic parasitemia and malaria transmission. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2013;11:623–639. doi: 10.1586/eri.13.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumsden WH. Quantitative methods in the study of trypanosomes and their applications: With special reference to diagnosis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1963;28:745–752. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor P, Savill NJ, Hall D, Matthews KR. Transmission stages dominate trypanosome within-host dynamics during chronic infections. Cell Host & Microbe. 2011;9:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magez S, Caljon G. Mouse models for pathogenic African trypanosomes: unravelling the immunology of host-parasite-vector interactions. Parasite Immunology. 2011;33:423–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makenga Bof JC, Maketa V, Bakajika DK, Ntumba F, Mpunga D, Murdoch ME, Hopkins A, Noma MM, Zouré H, Tekle AH, Katabarwa MN, Lutumba P. Onchocerciasis control in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): challenges in a post-war environment. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2015;20:48–62. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern TW, Williams W, Fitzpatrick JE, Cetron MS, Hepburn BC, Gentry RH. Cutaneous manifestations of African trypanosomiasis. Archives of Dermatology. 1995;131:1178–1182. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1995.01690220084016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myburgh E, Coles JA, Ritchie R, Kennedy PG, McLatchie AP, Rodgers J, Taylor MC, Barrett MP, Brewer JM, Mottram JC. In vivo imaging of trypanosome-brain interactions and development of a rapid screening test for drugs against CNS stage trypanosomiasis. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotureau B, Subota I, Buisson J, Bastin P. A new asymmetric division contributes to the continuous production of infective trypanosomes in the tsetse fly. Development. 2012;139:1842–1850. doi: 10.1242/dev.072611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks D, Lawyer P, Kamhawi S. The biology of Leishmania–sand fly interactions. In: Myler P, editor. Leishmania After the Genome. 2008. pp. 205–238. [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y. Leishmania and Sandflies: interactions in the life cycle and transmission. Parasitology Today. 1993;9 doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(93)90070-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simarro PP, Cecchi G, Franco JR, Paone M, Diarra A, Ruiz-Postigo JA, Fèvre EM, Mattioli RC, Jannin JG. Estimating and mapping the population at risk of sleeping sickness. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012;6:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steverding D. The history of African trypanosomiasis. Parasites & Vectors. 2008;1:e17716. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tait A, Babiker EA, Le Ray D. Enzyme variation in Trypanosoma brucei spp. I. Evidence for the sub-speciation of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Parasitology. 1984;89:311–326. doi: 10.1017/S0031182000001335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trindade S, Rijo-Ferreira F, Carvalho T, Pinto-Neves D, Guegan F, Aresta-Branco F, Bento F, Young SA, Pinto A, Van Den Abbeele J, Ribeiro RM, Dias S, Smith TK, Figueiredo LM. Trypanosoma brucei parasites occupy and functionally adapt to the adipose tissue in mice. Cell Host & Microbe. 2016;19 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walrad P, Paterou A, Acosta-Serrano A, Matthews KR. Differential trypanosome surface coat regulation by a CCCH protein that co-associates with procyclin mRNA cis-elements. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e17716. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wombou Toukam CM, Solano P, Bengaly Z, Jamonneau V, Bucheton B. Experimental evaluation of xenodiagnosis to detect trypanosomes at low parasitaemia levels in infected hosts. Parasite. 2011;18:295–302. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2011184295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Department of Epidemic and Pandemic Alert and Response . WHO Report on Global Surveillance of Epidemic-Prone Infectious Diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Control and surveillance of human African trypanosomiasis. World Health Organization Technical Report Series. 2013:1–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xong HV, Vanhamme L, Chamekh M, Chimfwembe CE, Van Den Abbeele J, Pays A, Van Meirvenne N, Hamers R, De Baetselier P, Pays E. A VSG expression site-associated gene confers resistance to human serum in Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Cell. 1998;95:839–846. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamze SE, Ferguson MA, Collins R, Dwek RA, Rademacher TW. Characterization of the cross-reacting determinant (CRD) of the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol membrane anchor of Trypanosoma brucei variant surface glycoprotein. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1988;176:527–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]