Abstract

Introduction

Despite the significant morbidity and mortality associated with alcoholic hepatitis, a consensus or generally accepted therapeutic strategy has not yet been reached. The purpose of this analysis was to evaluate the effects of corticosteroids and pentoxifylline on short-term mortality, incidence of hepatorenal syndrome, and sepsis in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search of the Cochrane library, PUBMED, Scopus, EMBASE, and published proceedings from major hepatology and gastrointestinal meetings from January 1970 to June 2015. All relevant articles irrespective of language, year of publication, type of publication, or publication status were included. Two independent reviewers extracted data and scored publications; a third investigator adjudicated discrepancies. Kappa scores were measured to assess the agreement between the two initial reviewers. The review and meta-analyses were performed following the recommendations of The Cochrane Collaboration. Conventional meta-analysis and Trial sequential analysis were performed. GRADEpro version 3.6 was used to appraise the quality of epidemiologic evidence.

Results

A total of 14 studies satisfied inclusion criteria comparing corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, or placebo. Compared to placebo, corticosteroids reduced 28-day mortality [RR 0.53 (95% CI: 0.33–0.84; p=0.006)]. There was no statistically significant difference in short-term mortality between pentoxifylline and placebo [RR 0.74 (95% CI: 0.46–1.18; p=0.21)]. Neither corticosteroids nor pentoxifylline impacted the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome or sepsis. Trial sequential analysis confirmed the results of our conventional meta-analysis.

Conclusions and Relevance

Corticosteroids demonstrated a decrease in 28-day mortality in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. The evidence from this study is insufficient to support any recommendations regarding the mortality benefit of pentoxifylline in severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Keywords: Corticosteroids, Pentoxifylline, Alcoholic Hepatitis, Liver Disease, Meta-Analysis, Trial Sequential Analysis

INTRODUCTION

Alcoholic hepatitis is a severe manifestation of alcoholic liver disease associated with significant morbidity and mortality. Short-term mortality rates with severe alcoholic hepatitis (defined clinically as having a Maddrey’s discriminant function ≥ 32 and/or developing hepatic encephalopathy) have been shown to be approximately 25 to 45%.1–4 The principal causes resulting in this significant mortality are secondary to hepatic failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and sepsis (55%, 21%, and 7%, respectively).1 Other factors associated with increased mortality include older age, worsening renal function, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated international normalized ratio, and leukocytosis.5–7 While the amount of required alcohol intake to place an individual at risk for alcoholic hepatitis is not well established and varies by patient, a history of heavy alcohol use defined as greater than 100 g/day for two or more decades has been suggested.8–11

Given the significant morbidity and mortality associated with alcoholic hepatitis, a number of potential therapies have been proposed and evaluated including corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, N-acetylcysteine, and anti-tumor necrosis factor-antibodies. Even transplant has been suggested for severe cases of alcoholic hepatitis though the role for this potential modality remains highly controversial.12–15 Although many potential therapies have been investigated, the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) only recommend the use of corticosteroids and pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis.16,17 Despite these recommendations, clinical practice and decision to treat remains largely heterogeneous, with controversy surrounding anecdotal evidence.

Although there are data demonstrating treatment efficacy in placebo-controlled trials, comparative effectiveness studies and meta-analyses have shown conflicting results. Corticosteroids have been advocated previously for severe alcoholic hepatitis, though studies to date have shown varied results with an unclear proven benefit. The Steroids or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) study was a recently published randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled comparative trial, which found that neither pentoxifylline nor prednisolone reduced 28-day mortality, 90-day mortality, or 1-year mortality.18 While this study demonstrated that pentoxifylline did not improve survival, prednisolone was associated with a reduction in 28-day mortality that did not reach statistical significance. A recent systematic review and network meta-analyses suggested a short-term mortality benefit in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis who received corticosteroid therapy alone or in combination with pentoxifylline.19 Yet despite these new data, confusion still exists regarding whether clinicians should rely upon a smaller, well-conceived randomized study or side with a higher-powered meta-analysis to make evidence-based decisions in the management of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Often, clinicians’ own familiarity and anecdotal evidence supersede the data when conflicting data persists.

Direct pairwise meta-analyses and network meta-analysis are frequently used to assess comparative effectiveness of therapies, but repeated comparisons (i.e. repeated significance testing of cumulative randomized trial data) raises the risk for type 1 error (falsely obtaining a “positive result” by chance) and small subject numbers or outcomes increase the risk for random error; both of which threaten study validity.20–24 In response, trial sequential analyses have recently been utilized to assess the comparative effectiveness of treatments for severe alcoholic hepatitis.21 This technique reduces type 1 error risk from multiple comparisons and sparse data.20–22,24

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of corticosteroids and pentoxifylline on short-term mortality, incidence of hepatorenal syndrome, and sepsis so as to provide an evidence base on which health care providers can make treatment decisions for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search Strategy and Data Extraction

Two authors independently conducted a comprehensive search of the Cochrane library, PUBMED, Scopus, EMBASE, and published proceedings from major hepatology and gastrointestinal meetings from January 1970 to June 2015. The search was conducted using the key words “Corticosteroids or Prednisone or Prednisolone or Pentoxifylline or Trental”, and “Alcoholic hepatitis or Alcohol-induced hepatitis”. All relevant articles irrespective of language, year of publication, type of publication, or publication status were included. Data from observational studies were excluded. The titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant studies were screened for eligibility. The reference lists of studies of interest were then manually reviewed for additional articles. In the case of studies with incomplete information, the principal authors were contacted to obtain additional data.

Measured Outcomes

Primary outcomes included short-term mortality (28-day or one-month mortality), all incident hepatorenal syndrome, and the incidence of sepsis in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.

Assessment of Risk of Bias in Included Studies

The methodological quality of the trials and associated risk of bias was assessed by: allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding or outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, vested interest bias, and other bias. We followed the guidelines set forth by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and the Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group Module.25

Assessment of Quality of Evidence Across Studies

We assessed the quality of the body of evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology. This method defines the quality of evidence for each outcome as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the quantity of specific interest. The quality rating across studies includes four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low. Randomized controlled trials are categorized as high quality but can be downgraded. Factors that decrease the quality of evidence include limitations in design, indirectness of evidence, risk of bias, unexplained heterogeneity or inconsistency, imprecision of results, or high probability of publication bias.26 We used the GRADEpro version 3.6 software of the Cochrane Collaboration to perform our analyses.

Data synthesis and Statistical Analysis

Two independent reviewers extracted data and scored publications; a third investigator adjudicated discrepancies. Kappa scores were measured to assess the agreement between the two initial reviewers in each step and interpreted as described.27,28 We performed the review and meta-analysis following the recommendations of The Cochrane Collaboration.29

We first performed a conventional pairwise meta-analysis with random effects models to synthesize studies comparing the same pair of treatments. The results were reported as pooled risk ratios with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Regression analyses were performed to estimate funnel plot asymmetry.27,28,30 Heterogeneity was evaluated with chi-square testing and I2 testing with significance limit set at a p-value of 0.10. Percentage of variation across studies due to heterogeneity, represented as I2, and was defined as low, moderate, or high heterogeneity (0.25, 0.5, 0.75, respectively). In the case of trials with zero outcome events, we applied an empirical continuity correction of 0.5 in both arms to avoid overestimating a treatment effect. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement outline for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses was used to report findings.31 All pairwise calculations were performed using REVIEW MANAGER Version 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, United Kingdom).

Second, we carried out a trial sequential analysis using the TSA software (TSA version 0.9; Copenhagen Trial Unit, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2011).32 Trial sequential analysis was performed for our primary outcome of 28-day mortality. Conventional pairwise meta-analysis uses Z-values to compare two interventions, with Z = 0 indicating no difference between groups.33 If Z exceeds ±1.96, a difference is traditionally assumed to be statistically significant (p < 0.05, two-sided test). For repeated updates of meta-analyses, a new Z-value is calculated for each update. In trial sequential analysis, this series of Z-values are plotted against the accumulated number of patients, outcomes, or information.24 This cumulative Z-curve is then assessed regarding its relation to the conventional significance boundaries (Z = ±1.96), the required information size, and the trial sequential monitoring boundaries (TSBM).

In trial sequential analysis, risk of type I error was set at α = 0.05. The risk of type II error was set at β = 0.20 equivalent to a power of 0.80. Relative risk reduction was defined a priori as a worthwhile interventional effect of 20%.34 The resulting required information size was further heterogeneity-adjusted (HIS) using the observed diversity.28 The Lan-DeMets version of the O’Brien–Fleming function was used for calculating TSMB.35,36 Results crossing the conventional boundary of significance (Z = ±1.96) but not the superiority or inferiority TSMB were defined as spuriously significant. Firm evidence of superiority or inferiority was assumed to be reached if the Z-curve crossed the required HIS and the conventional boundaries hereafter or crossed the superiority or inferiority TSMBs before the required information size was reached. Firm evidence of futility was confirmed by the Z-curve crossing the futility TSBM.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Included Studies

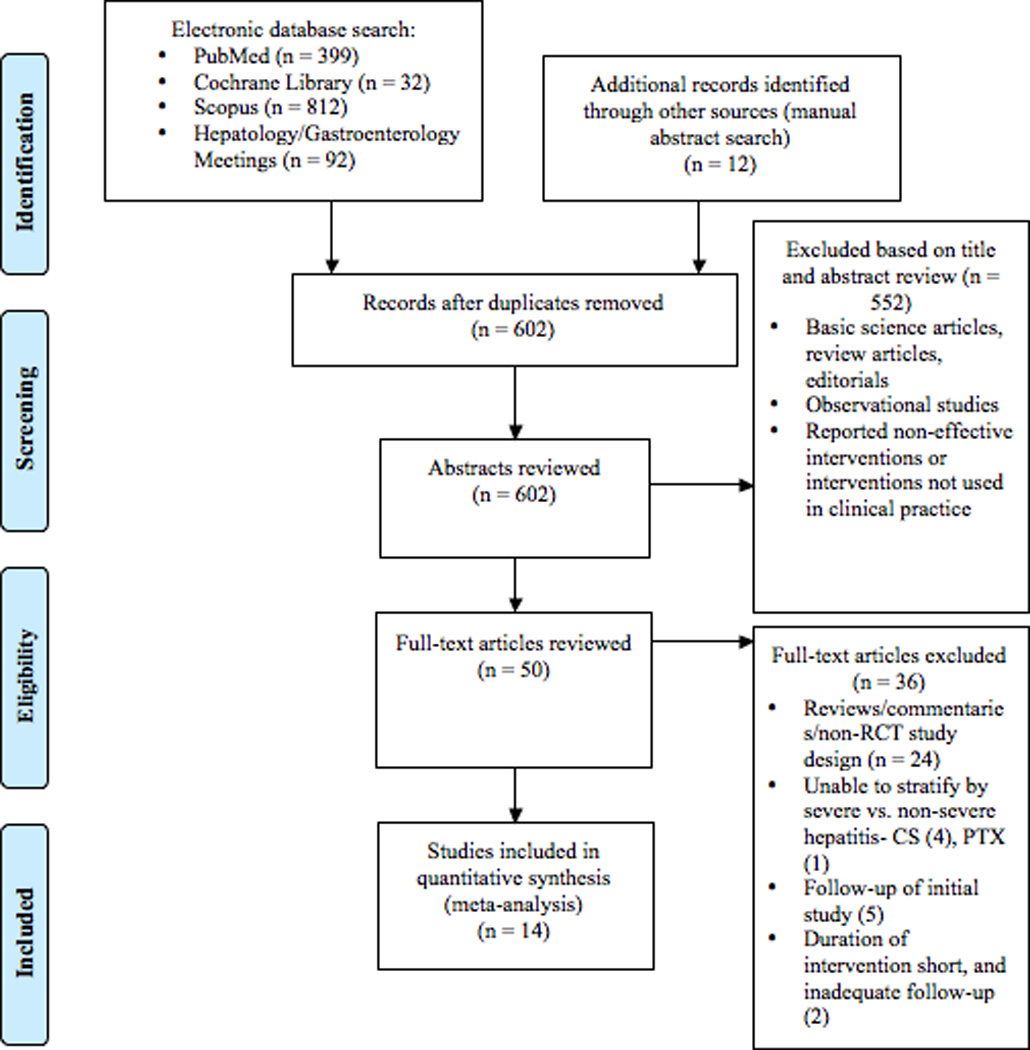

A total of 14 studies met inclusion criteria based upon the search related terms as detailed above.4,11,18,37–47 A PRISMA flow chart of the literature search and selection process is shown in Figure 1. There was an excellent inter-reviewer agreement [Kappa = 0.93 (95% CI: 0.66–1.0)]. The characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 1, six of which included studies utilizing an intention-to-treat analysis.11,18,39,45–47 The remaining studies were either per-protocol or this information was not stated.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the literature search and selection process.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies for Management of Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis

| Author | Year of Study |

Study Design |

Duration follow-up (months) |

Pharmaco- therapy of Study |

Number of Patients Treated |

% With Biopsy Confirmation |

Average Age in Years (SD) |

Sex, M/F (%) |

Average MELD Score (SD) |

Average Child- Pugh Score (SD) |

MDF Score (SD) |

Bilirubin µmol/L (SD) |

Creatinine mg/dL (SD) |

INR (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | CS vs Placebo |

274 | 18.9% | 49 (11) | 65/35 | 21 (6) | - | 61 (25) | 17.4 (9.1) | 0.9 (0.5) | - |

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | PTX vs Placebo |

273 | 48 (10) | 60/40 | 21 (6) | - | 66 (32) | 17.1 (8.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | - | |

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | CS + PTX vs Placebo |

273 | 49 (10) | 67/33 | 22 (7) | - | 62 (26) | 17.9 (9.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | - | |

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | CS vs PTX |

- | 49 (10) | 65/35 | 21 (6) | - | 62 (25) | 17.4 (9.1) | 0.9 (0.5) | - | |

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | CS + PTX vs CS |

- | 49 (10) | 67/33 | 22 (7) | - | 62 (26) | 17.9 (095) | 0.9 (0.6) | - | |

| Thurz et al. | 2015 | RCT | 12 | CS + PTX vs PTX |

- | 49 (10) | 67/33 | 22 (7) | - | 62 (26) | 17.9 (9.5) | 0.9 (0.6) | - | |

| Park et al. | 2014 | RCT | 6 | CS vs PTX | 59 | - | 48 (9) | 68/32 | 26* | - | 65 (26) | 18.2 (9.4) | 1.0 (0.9) | 2.1 (0.7) |

|

Garrido Garcia et al. |

2012 | RCT | 1 | CS vs PTX | 30 | - | 45 (12) | 93/7 | 32* | - | 83 (35) | 20.6 (9.6) | 2.0 (1.5) | 2.0 (0.6) |

| Sidhu et al. | 2012 | RCT | 1 | PTX vs Placebo |

25 | - | - | 100/0 | - | - | 79 (64) | 21.6 (11.3) | 1.2 (0.8) | - |

| De et al. | 2009 | RCT | 12 | CS vs PTX | 34 | - | 46 (10) | 97/3 | 23 (3) | 12 (1) | 58 (17) | 46.6 (3.9) | 1.2 (0.3) | 2.0 (0.3) |

|

Paladugu et al. |

2006 | RCT | 1 | PTX vs Placebo |

25 | - | 50 (6) | 100/0 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Cabre et al. | 2000 | RCT | 12 | CS vs Placebo |

36 | 52% | 49 (11) | 72/28 | - | 11 (1) | 50 (16) | 16.3 (10.8) | 0.9 (0.4) | - |

|

Akriviadis et al. |

2000 | RCT | 6 | PTX vs Placebo |

52 | - | 42 (8) | 71/29 | 39* | - | 46 (12) | 18.5 (.5) | 1.2 (0.9) | 6 (2.4) |

|

Ramond et al. |

1992 | RCT | - | CS vs Placebo |

32 | 100% | 48 (7) | 31/69 | - | - | 51 (23) | 12.4 (8.3) | 1.0 (0.7) | - |

|

Carithers et al. |

1989 | RCT | 1 | CS vs Placebo |

35 | - | 43 (12) | 57/43 | - | - | 46 (12) | 16.8 (9.1) | 1.5 (1.4) | - |

|

Depew et al. |

1980 | RCT | 2 | CS vs Placebo |

15 | - | 50 (8) | 67/33 | - | - | - | 24.7 (10.5) | 2.3 (1.6) | - |

|

Lesene et al. |

1978 | RCT | - | CS vs Placebo |

7 | 78.6% | 45 (8) | 86/14 | 40* | - | - | 25.8 (9.4) | 2.1 (1.7) | 5.4 (2.4) |

|

Maddrey et al. |

1978 | RCT | - | CS vs Placebo |

24 | - | 40 (9) | 50/50 | - | - | - | 11.8 (11) | 1.2 (1.0) | - |

|

Helman et al. |

1971 | RCT | - | CS vs Placebo |

20 | 100% | 48 (7) | 33/67 | - | - | - | 13.1 (10.1) | - | - |

Calculated MELD based upon available average study data (average bilirubin, creatinine, INR)

Short-Term Mortality

Corticosteroids versus Placebo

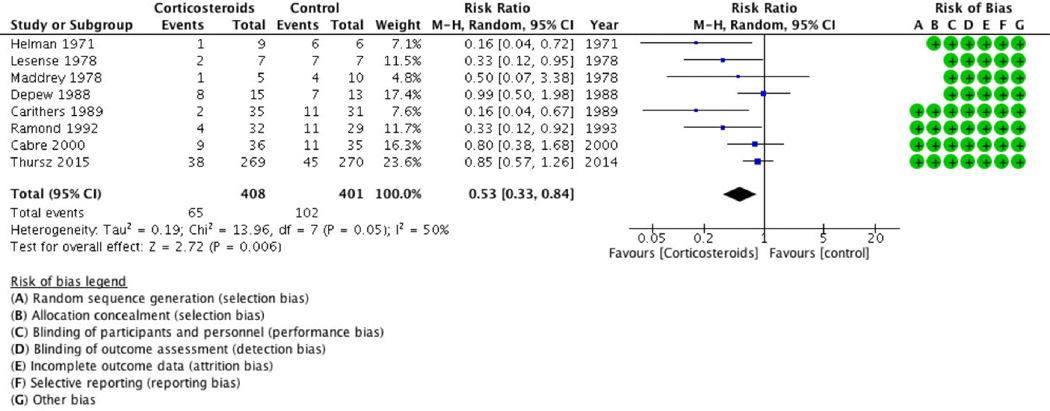

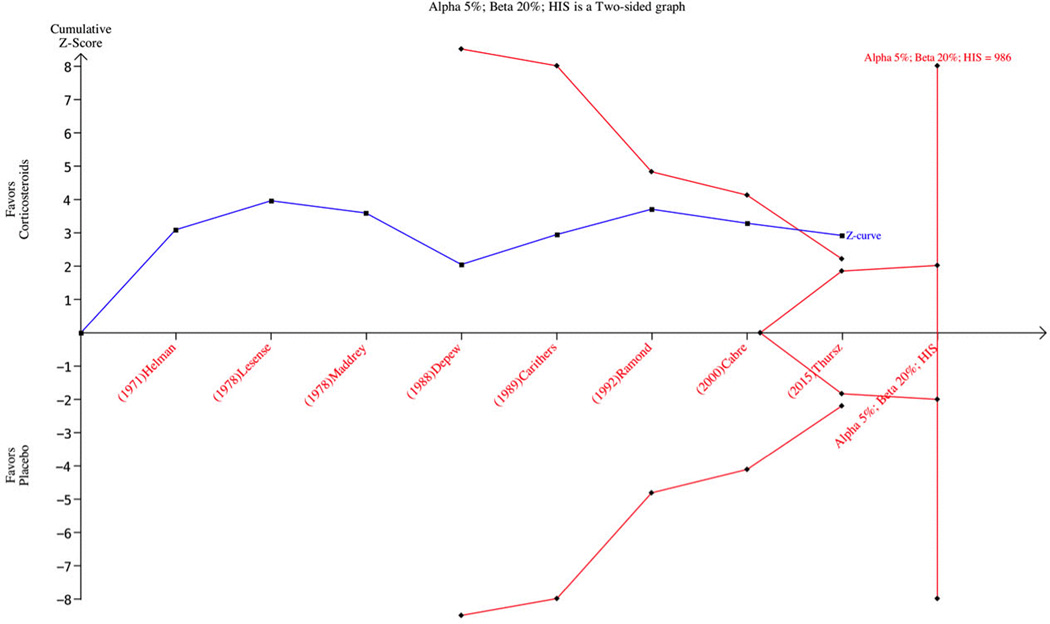

Eight studies were included comparing corticosteroids versus placebo in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.4,18,39,40,42–44,46 In pairwise meta-analysis, corticosteroids were more effective than placebo in decreasing short-term mortality with an overall effect estimate of 0.53 (95% CI: 0.33–0.84; p = 0.006, Figure 2). In our trial sequential analysis, the HIS based on a relative risk of 0.80 (mortality in the control group of 50%, alpha = 5%, and beta = 20%) was 986 patients (Figure 3). While the required information size was not achieved, the Z-score crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary and demonstrated sufficient evidence to suggest corticosteroids improve short-term mortality. Two studies reported average Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores for stratification purposes with both favoring the use of corticosteroids versus placebo.18,44 The patients recruited by Lesense and colleagues who had a significantly higher calculated MELD score (mean MELD score 40) also demonstrated a more effective response to corticosteroids as compared to Thursz et al (mean MELD score 21).

Figure 2.

Forest Plot: Short-term mortality of Corticosteroids versus Placebo.

Figure 3.

Trial sequential analysis: Short-term mortality of Corticosteroids versus Placebo. The heterogeneity-adjusted information (HIS) based on a relative risk of 0.80 (mortality in the control group of 50%, alpha = 5%, and beta = 20%) was 986 patients. While the required information size was not achieved, the Z-score crossed the trial sequential monitoring boundary and demonstrated sufficient evidence to suggest corticosteroids improve short-term mortality.

Symmetric funnel plot indicated a low probability of publication bias (Supplemental Figure 1). Calculated heterogeneity showed Chi2 = 13.96, I2 = 50% indicating significant heterogeneity. The summary of findings and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) results for corticosteroids versus placebo are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) : Corticosteroids compared to Placebo for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis

| Quality assessment | № of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations |

Corticosteroids | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) |

Absolute (95% CI) |

||

| Short Term Mortality | ||||||||||||

| 8 | Randomized trials |

Not Serious |

Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | Strong Association |

65/408 (15.9%) |

102/401 (25.4%) |

RR 0.53 (0.33 to 0.84) |

120 fewer per 1000 (from 41 fewer to 170 fewer) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| 33.5% | 157 fewer per 1000 (from 54 fewer to 224 fewer) |

|||||||||||

| Hepatorenal Syndrome | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials |

Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | None | 12/317 (3.8%) | 15/317 (4.7%) |

RR 0.81 (0.39 to 1.70) |

9 fewer per 1000 (from 29 fewer to 33 more) |

⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| 2.9% | 5 fewer per 1000 (from 17 fewer to 20 more) |

|||||||||||

| Sepsis | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Randomized trials |

Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | None | 70/391 (17.9%) |

56/384 (14.6%) |

RR 1.00 (0.55 to 1.80) |

0 fewer per 1000 (from 66 fewer to 117 more) |

⊕⊕⊕ ◯ MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| 48.4% | 0 fewer per 1000 (from 218 fewer to 387 more) |

|||||||||||

MD – mean difference, RR – relative risk

Pentoxifylline versus Placebo

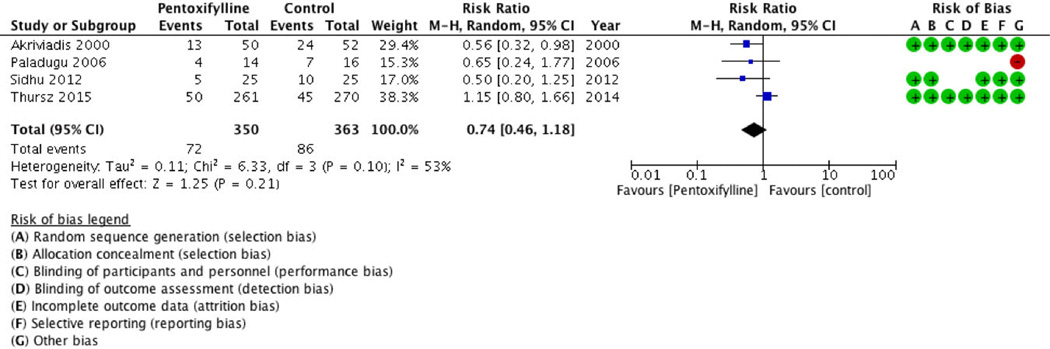

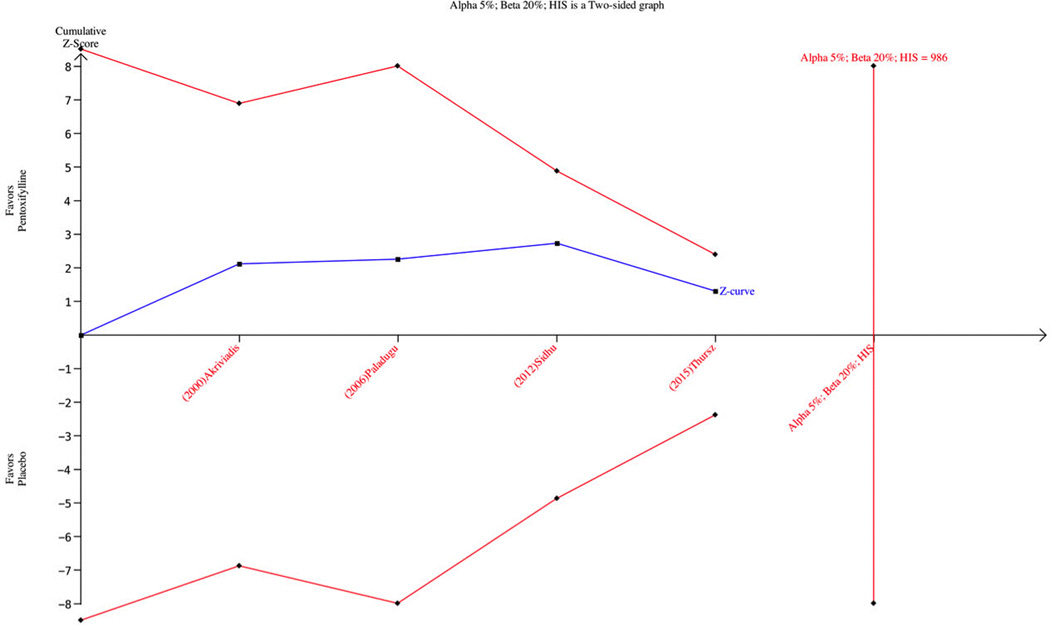

A total of 4 studies compared pentoxifylline to placebo in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis.11,18,37,47 There was no statistically significant decrease in short-term mortality when pentoxifylline was compared to placebo [RR 0.74 (95% CI: 0.46–1.18; p=0.21, Figure 4)]. One study favored placebo compared to pentoxifylline. Calculated heterogeneity showed Chi2 = 6.33, I2 = 53% indicating moderate heterogeneity. Trial Sequential Analysis (Figure 5) confirmed the results of our conventional meta-analysis by demonstrating futility (non-superiority and non-inferiority). The summary of findings and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) results for pentoxifylline versus placebo are summarized in Table 3.

Figure 4.

Forest Plot: Short-term mortality of Pentoxifylline versus Placebo.

Figure 5.

Trial sequential analysis: Short-term mortality of Pentoxifylline versus Placebo. The heterogeneity-adjusted information (HIS) based on a relative risk of 0.80 (mortality in the control group of 50%, alpha = 5%, and beta = 20%). Trial Sequential Analysis demonstrates futility (non-superiority and non-inferiority).

Table 3.

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) : Pentoxifylline compared to Placebo for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis

| Quality assessment | № of patients | Effect | Quality | Importance | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| № of studies |

Study design |

Risk of bias |

Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations |

Pentoxifylline | Placebo | Relative (95% CI) |

Absolute (95% CI) |

||

| Short Term Mortality | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials |

Not Serious |

Not Serious | Not Serious | Not Serious | None | 72/350 (20.6%) |

86/363 (23.7%) |

RR 0.74 (0.46 to 1.18) |

62 fewer per 1000 (from 43 more to 128 fewer) |

⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH |

CRITICAL |

| 41.9% | 109 fewer per 1000 (from 75 more to 226 fewer) |

|||||||||||

| Hepatorenal Syndrome | ||||||||||||

| 4 | Randomized trials |

Not Serious |

Not Serious | Not Serious | Serious | None | 20/347 (5.8%) |

41/362 (11.3%) |

RR 0.45 (0.17 to 1.16) |

62 fewer per 1000 (from 18 more to 94 fewer) |

⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| 19.2% | 105 fewer per 1000 (from 31 more to 159 fewer) |

|||||||||||

| Sepsis | ||||||||||||

| 3 | Randomized trials |

Not Serious |

Not Serious | Serious | Not Serious | None | 30/344 (8.7%) |

22/335 (6.6%) |

RR 1.30 (0.77 to 2.20) |

20 more per 1000 (from 15 fewer to 79 more) |

⊕⊕⊕◯ MODERATE |

IMPORTANT |

| 11.5% | 35 more per 1000 (from 27 fewer to 138 more) |

|||||||||||

MD – mean difference, RR – relative risk

Corticosteroids versus Pentoxifylline

Four comparator studies were included comparing corticosteroids versus pentoxifylline. The overall effect estimate in patients with alcoholic hepatitis was 0.95 (95% CI: 0.55–1.64; p=0.85, Supplemental Figure 2), and was not statistically significant. In trial sequential analysis, the Z-curve did not cross the traditional significance boundaries, and no firm evidence was reached (Supplemental Figure 3).

Hepatorenal Syndrome

Corticosteroids versus Placebo

Three studies described incident hepatorenal syndrome in relation to corticosteroids versus placebo. Forest plot of the corticosteroids versus placebo group demonstrated a RR of 0.81 (95% CI: 0.39–0.1.70; p=0.57, Supplemental Figure 4), which was not statistically significant. Heterogeneity testing revealed complete homogeneity between the 3 studies (Chi2 = 1.45 and I2 = 0%).

Pentoxifylline versus Placebo

We included 4 studies comparing pentoxifylline to placebo. The RR was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.17–1.16; p=0.10, Supplemental Figure 5) - not statistically significant. One study favored placebo compared to pentoxifylline for the prevention of hepatorenal syndrome in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Calculated heterogeneity revealed Chi2 = 7.76 and I2 = 61% indicating moderate heterogeneity.

Corticosteroids versus Pentoxifylline

Four studies were included comparing corticosteroids versus pentoxifylline. Overall effect estimate in regard to hepatorenal syndrome was 0.81 (95% CI: 0.38–1.77; p=0.60, Supplemental Figure 6).

Sepsis

Corticosteroids versus Placebo

A total of 6 studies described the incidence of sepsis in relation to corticosteroids versus placebo. The RR was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.55–0.1.80; p=0.99, Supplemental Figure 7), which was not statistically significant.

Pentoxifylline versus Placebo

Three studies detailed the incidence of sepsis and compared pentoxifylline to placebo. The overall effect estimate was 1.3 (95% CI, 0.77–2.20; p=0.33, Supplemental Figure 8).

Corticosteroids versus Pentoxifylline

Four studies comparing corticosteroids versus pentoxifylline were included. There was no statistically significant decrease in short-term mortality when corticosteroids were compared to pentoxifylline [RR 1.62 (95% CI, 0.89–2.96; p=0.612, Supplemental Figure 9)].

DISCUSSION

This sequential analysis of randomized control trials suggests that there is a short-term mortality benefit with corticosteroids use compared to placebo. However, pentoxifylline use was not associated with improvement in short-term mortality. Neither the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome nor sepsis risk was influenced by corticosteroids or pentoxifylline therapy.

Despite a large number of comparative and non-comparative individual studies along with meta-analyses to evaluate the effectiveness of different treatments for alcoholic hepatitis, a consensus or generally accepted therapeutic strategy has not yet been reached. While the STOPAH trial showed neither prednisolone nor pentoxifylline to significantly reduce 28-day mortality, prednisolone showed a trend toward improving survival (OR 0.72, 95% CI: 0.52–1.01).18 A subsequent systematic review and network meta-analysis demonstrated pentoxifylline and corticosteroids (alone or in combination with pentoxifylline or N-acetylcysteine) may reduce short-term mortality19. While this may appear to be a complete summary of all available trials, it is important to note the inherent limitations of this study modality. Traditional meta-analysis may be prone to random errors, especially when evaluating results of only few early trials with limited quality and small number of patients.21,23 In addition, repeated significance testing when updating meta-analyses might generate erroneous results.32,48 Validity concerns when using network meta-analyses involve conceptual heterogeneity (i.e. inconsistency or incoherence) whereby differences exist between study participants, intervention or treatment arms, and outcome assessment – thus limiting comparability of trials.19,20,26

Using both conventional meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis, we demonstrated that there is sufficient evidence that corticosteroids, when compared to placebo, improve short-term mortality. The subsequent trial sequential analysis demonstrated that the Z-curve crossed the monitoring boundary in 2015 after the addition of the STOPAH trial (Figure 3). At this time, based upon the eight studies included, we have firm evidence to show the benefits of corticosteroids on short-term mortality. This suggests that more trials are not needed to show a short-term benefit for corticosteroids in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Trial sequential analysis also illustrated that short-term mortality was not decreased in patients receiving pentoxifylline. Futility (non-superiority and non-inferiority) was shown when pentoxifylline was compared to placebo and no firm evidence was reached when corticosteroids were compared to pentoxifylline.

The secondary aims of this study were to assess the comparative effectiveness of corticosteroids, pentoxifylline, and placebo regarding the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome and sepsis. Compared to placebo, neither corticosteroids nor pentoxifylline revealed a statistically significant difference in the incidence or prevention of hepatorenal syndrome. It is important to note that the 3 studies addressing corticosteroids versus placebo with regard to hepatorenal syndrome were completely homogenous. The incidence of sepsis associated with alcoholic hepatitis was also examined in regard to potential drug treatments. Similarly, corticosteroids when compared to placebo, pentoxifylline when compared to placebo, and corticosteroids when compared directly to pentoxifylline showed no statistical significance in improvement. Despite the robustness of this data, no included study provided a clear definition of sepsis or hepatorenal syndrome upon literature review. Further homogenous studies are warranted to explore the relationship of both corticosteroids and pentoxifylline on the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome and sepsis.

This study, like all analyses pooled from previous studies, possessed intrinsic heterogeneity. There was variation of the characteristics of included patients and intervention regimens. As a result, there was some evidence of heterogeneity in our overall analyses. This can be considered both a weakness and strength. Minimal variation of the intervention regimen would have provided a more focused answer. However, an increased variation of patients and intervention regimens increased the external validity of the results. Also, it is important to note variation occurred between the studies regarding the definition of placebo. At least 2 studies (Lesenne et al and Cabre et al) used nutrition as a control intervention.39,44 No subgroup analysis was performed for different controls and it has been suggested that nutrition may improve encephalopathy in patients with alcoholic hepatitis.49 Additionally, this variation can be extended to the type of analysis performed (i.e. intention-to-treat versus per-protocol). As only six studies explicitly stated an intention-to-treat analysis (a minority of included studies), our results may be limited in the ability to assess the true value of these pharmacotherapies as they relate to a heterogeneous population.

Funnel plot asymmetry was performed to assess publication bias for corticosteroids versus placebo in regards to 28-day mortality. While traditionally funnel plot should only be applied when there includes 10 or more studies, the 8 studies included for this outcome were plotted for full regression analysis. While this rule of thumb regarding the number of studies is aimed to prevent lower powered studies and reduce the chance for true asymmetry, we argue given an overall lack of data, the funnel plot is needed and remains an accurate representation and summary of all available data.

At the heart of any challenge to this study’s validity is the realization that physicians are limited by the ability to accurately diagnose alcoholic hepatitis clinically without reliance on liver biopsy. Despite the numerous scoring and severity systems (most commonly the Maddrey’s discriminant function), many of the included studies showed a negative confirmation of disease on liver biopsy – Table 1. In a recent study by Hardy and colleagues, 58 patients with a clinical diagnosis of alcoholic hepatitis and Maddrey’s discriminant function ≥ 32 underwent liver biopsy demonstrating only 42 cases to have the histological evidence (accurate only 73.41% of the time).50 Subsequent multivariate analysis of patient clinical features revealed the white blood cell count and platelet level may help to suggest histologic alcoholic hepatitis. While the included studies in this analysis mainly relied upon the presence of Maddrey’s discriminant function ≥ 32 or the presence of hepatic encephalopathy, it remains unclear whether response rates differed secondary to inaccurate clinical diagnosis. Ultimately, while a variety of pharmacotherapies exist for the treatment of alcoholic hepatitis, any proposed therapies are only effective with an accurate diagnosis – suggesting an increased role for liver biopsy to confirm diagnosis.

Despite this inescapable limitation, our results are in accordance with Singh and colleague’s recently published network meta-analysis regarding the role for corticosteroids alone.19 As found in the STOPAH trial, our conventional meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis revealed 28-day mortality was not decreased in pentoxifylline treated individuals with alcoholic hepatitis.18 Furthermore, this study did not address the role of alternative treatments for alcoholic hepatitis such as N-acetylcysteine and anti-tumor necrosis factor-antibodies – one of which is highlighted and its use supported by Singh and colleagues.

In translation of this analysis to clinical practice, our study suggests that for patients who develop severe alcoholic hepatitis, corticosteroids improve 28-day mortality compared to no treatment. Conversely, based upon this analysis, the evidence supporting a mortality benefit for pentoxifylline in the management of alcoholic hepatitis is lacking. Additionally, when corticosteroids were compared to placebo and stratified by MELD score, steroid therapy appeared to be more effective for patients with higher MELD scores.18,44 This suggests corticosteroids may be more effective based upon the severity or degree of alcoholic hepatitis (i.e. more efficacious for sicker patients). Yet it remains unclear as to the existence of a specific subset of patients with higher MELD scores that may not benefit from treatment (presumably those with active infection, hepatorenal syndrome, or other co-morbidities). A further delineation or stratification of patients with higher MELD scores to determine true responders versus non-responders may be warranted.

While the MELD score has been proposed for the assessment of alcoholic hepatitis, the MELD score has never been shown to be statistically superior to Maddrey’s discriminant function.51–54 Previous studies attempting to identify a MELD score threshold, or optimal decision-point upon which to initiate corticosteroid therapy have varied widely. Despite this, the AASLD has proposed a MELD score of 18 based upon the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) modification of the MELD score upon which to initiate corticosteroid therapy.55 While this precise value remains unknown, our results suggest an even greater efficacy for patients with higher MELD scores. It is important to note, the MELD score, and thus the results of our study as well, may be skewed by the presence of absence of cirrhosis. Further, this meta-analysis does not address the decision to discontinue corticosteroid treatment based upon a failure of the bilirubin to decline or score greater than 0.45 as determined by the Lille model by day 7 of treatment.56

Even with this data, clinicians may continue to find it exceedingly difficult to treat patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis – compounded by the inability to accurately diagnosis the disease without liver biopsy. Despite a high degree of alcoholic related liver disease in the United States and worldwide, few effective treatments exist. There exists a vacuum between the number of patients with alcoholic hepatitis and the success of current treatment strategies and future research underway for other potential measures. Given this disconnect, clinicians may continue to rely upon anecdotal evidence until a true organizational guideline is published or consensus reached.

In conclusion, our analysis demonstrated corticosteroids reduce the risk for short-term mortality as treatment for severe alcoholic hepatitis. No treatment was associated with an increasing incidence of hepatorenal syndrome or sepsis. The evidence from this study is insufficient to support any recommendations regarding the mortality benefit of pentoxifylline in severe alcoholic hepatitis. Neither does this evidence demonstrate that pentoxifylline is unsafe in this group of patients. Our results suggest that clinicians should rely less upon pentoxifylline as a treatment modality for severe alcoholic hepatitis, but should continue to consider steroids as management for this disease. New guidelines are warranted to form a cohesive consensus to aid clinical management.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant Support (Funding):

Basile Njei is supported by the NIH T 32 Grant-DK007356

Abbreviations

- RR

Risk Ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Footnotes

Disclosure / Conflict of interest declaration: None

Writing Assistance: None.

Specific author contributions:

Study concept and design, paper preparation and Statistical analysis - Njei B

Paper preparation and critical revisions - Do A, McCarty TR, Fortune BE

Supplemental Figure 1: Funnel plot of Corticosteroids vs Placebo

Supplemental Figure 2: Forest Plot of Corticosteroids vs Pentoxifylline: Short-Term mortality

Supplemental Figure 3: TSA Plot of Corticosteroids vs Pentoxifylline: short-term Mortality

Supplemental Figure 4: Forest Plot of Corticosteroids vs Steroids: Hepatorenal Syndrome

Supplemental Figure 5: Forest Plot of Pentoxifylline vs Placebo: Hepatorenal Syndrome

Supplemental Figure 6: Forest Plot of Corticosteroids vs Pentoxifylline: Hepatorenal Syndrome

Supplemental Figure 7: Forest Plot of Corticosteroids vs Placebo: Sepsis

Supplemental Figure 8: Forest Plot of Pentoxifylline vs Placebo: Sepsis

Supplemental Figure 9: Forest Plot of Corticosteroids vs Pentoxifylline: Sepsis

References

- 1.Yu CH, Xu CF, Ye H, Li L, Li YM. Early mortality of alcoholic hepatitis: a review of data from placebo-controlled clinical trials. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2010;16:2435–2439. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i19.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imperiale TF, McCullough AJ. Do corticosteroids reduce mortality from alcoholic hepatitis? A meta-analysis of the randomized trials. Annals of internal medicine. 1990;113:299–307. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-4-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali S, Hussain S, Hair M, Shah AA. Comparison of Maddrey Discriminant Function, Child-Pugh Score and Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score in predicting 28-day mortality on admission in patients with acute hepatitis. Irish journal of medical science. 2013;182:63–68. doi: 10.1007/s11845-012-0827-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL, Jr, Mezey E, White RI., Jr Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 1978;75:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altamirano J, Fagundes C, Dominguez M, et al. Acute kidney injury is an early predictor of mortality for patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2012;10:65–71. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liangpunsakul S. Clinical characteristics and mortality of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis patients in the United States. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2011;45:714–719. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181fdef1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poynard T, Zourabichvili O, Hilpert G, et al. Prognostic value of total serum bilirubin/gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase ratio in cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 1984;4:324–327. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840040224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendenhall CL, Moritz TE, Roselle GA, et al. A study of oral nutritional support with oxandrolone in malnourished patients with alcoholic hepatitis: results of a Department of Veterans Affairs cooperative study. Hepatology. 1993;17:564–576. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840170407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naveau S, Giraud V, Borotto E, Aubert A, Capron F, Chaput JC. Excess weight risk factor for alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 1997;25:108–111. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathurin P, O'Grady J, Carithers RL, et al. Corticosteroids improve short-term survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gut. 2011;60:255–260. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.224097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akriviadis E, Botla R, Briggs W, Han S, Reynolds T, Shakil O. Pentoxifylline improves short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1637–1648. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucey MR. Liver transplantation for alcoholic liver disease. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014;11:300–307. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dom G, Wojnar M, Crunelle CL, et al. Assessing and treating alcohol relapse risk in liver transplantation candidates. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2015;50:164–172. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agu096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathurin P, Moreno C, Samuel D, et al. Early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365:1790–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Testino G, Burra P, Bonino F, et al. Acute alcoholic hepatitis, end stage alcoholic liver disease and liver transplantation: an Italian position statement. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2014;20:14642–14651. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i40.14642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ. Practice Guideline Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver D, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of G. Alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.European Association for the Study of L. EASL clinical practical guidelines: management of alcoholic liver disease. Journal of hepatology. 2012;57:399–420. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thursz MR, Richardson P, Allison M, et al. Prednisolone or pentoxifylline for alcoholic hepatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2015;372:1619–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh S, Murad MH, Chandar AK, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Pharmacological Interventions for Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2015 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cipriani A, Higgins JP, Geddes JR, Salanti G. Conceptual and technical challenges in network meta-analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;159:130–137. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-2-201307160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rambaldi A, Saconato HH, Christensen E, Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Gluud C. Systematic review: glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis--a Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group systematic review with meta-analyses and trial sequential analyses of randomized clinical trials. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2008;27:1167–1178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutton B, Salanti G, Chaimani A, et al. The quality of reporting methods and results in network meta-analyses: an overview of reviews and suggestions for improvement. PloS one. 2014;9:e92508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parker R, Armstrong MJ, Corbett C, Rowe IA, Houlihan DD. Systematic review: pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013;37:845–854. doi: 10.1111/apt.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:64–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puhan MA, Schunemann HJ, Murad MH, et al. A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. Bmj. 2014;349:g5630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2009;62:e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Estimating required information size by quantifying diversity in random-effects model meta-analyses. BMC medical research methodology. 2009;9:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saconato H, Di Sena V, Gluud C, Chris- tensen E, Atallah A. Glucocorticosteroids for alcoholic hepatitis (Protocol) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1999;(1) Art. No.: CD001511. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC. What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Statistics in medicine. 2004;23:1351–1375. doi: 10.1002/sim.1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liberati AAD, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thorlund K, Wetterslev J, Brok J, Imberger G, Gluud C. User manual for Trial Sequential Analysis (TSA) [accessed 9 July 2015]; http://ctu.dk/tsa/files/tsa_manual.pdf 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu G, Ades AE. Combination of direct and indirect evidence in mixed treatment comparisons. Stat Med. 2004;23:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Keus F, Wetterslev J, Gluud C, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Trial sequential analyses of meta-analyses of complications in laparoscopic vs. small-incision cholecystectomy: more randomized patients are needed. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2010;63:246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demets DL, Lan KKG. Interim analysis: The alpha spending function approach. Statistics in Medicine. 1994;13:1341–1352. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780131308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Brien PC, Fleming TR. A Multiple Testing Procedure for Clinical Trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paladugu HS, Dalvi P, Kudalkar L. Role of pentoxifylline in treatment of severe acute alcoholic hepatitis - a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:A459. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Garrido Garia JR, Sanchez Hernandez G, Melchor Lopez A, et al. Pentoxifylline versus steroid in short-term survival in severe acute alcoholic hepatitis. Med Int Mex. 2012;28:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cabre E, Rodriguez-Iglesias P, Caballeria J, et al. Short- and long-term outcome of severe alcohol-induced hepatitis treated with steroids or enteral nutrition: a multicenter randomized trial. Hepatology. 2000;32:36–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.8627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carithers RL, Jr, Herlong HF, Diehl AM, et al. Methylprednisolone therapy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. A randomized multicenter trial. Annals of internal medicine. 1989;110:685–690. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-9-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De BK, Gangopadhyay S, Dutta D, Baksi SD, Pani A, Ghosh P. Pentoxifylline versus prednisolone for severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomized controlled trial. World journal of gastroenterology : WJG. 2009;15:1613–1619. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Depew W, Boyer T, Omata M, Redeker A, Reynolds T. Double-blind controlled trial of prednisolone therapy in patients with severe acute alcoholic hepatitis and spontaneous encephalopathy. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:524–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helman RA, Temko MH, Nye SW, Fallon HJ. Alcoholic hepatitis. Natural history and evaluation of prednisolone therapy. Annals of internal medicine. 1971;74:311–321. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-3-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lesesne HR, Bozymski EM, Fallon HJ. Treatment of alcoholic hepatitis with encephalopathy. Comparison of prednisolone with caloric supplements. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:169–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park SH, Kim DJ, Kim YS, et al. Pentoxifylline vs. corticosteroid to treat severe alcoholic hepatitis: a randomised, non-inferiority, open trial. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramond MJ, Poynard T, Rueff B, et al. A randomized trial of prednisolone in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. The New England journal of medicine. 1992;326:507–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199202203260802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sidhu SS, Goyal O, Singla M, Bhatia KL, Chhina RS, Sood A. Pentoxifylline in severe alcoholic hepatitis: a prospective, randomised trial. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2012;60:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Higgins JPT, Whitehead A, Simmonds M. Sequential methods for random-effects meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2011;30:903–921. doi: 10.1002/sim.4088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Antar R, Wong P, Ghali P. A meta-analysis of nutritional supplementation for management of hospitalized alcoholic hepatitis. Canadian journal of gastroenterology = Journal canadien de gastroenterologie. 2012;26:463–467. doi: 10.1155/2012/945707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hardy T, Wells C, Kendrick S, et al. White cell count and platelet count associate with histological alcoholic hepatitis in jaundiced harmful drinkers. BMC gastroenterology. 2013;13:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dunn W, Jamil LH, Brown LS, et al. MELD accurately predicts mortality in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Hepatology. 2005;41:353–358. doi: 10.1002/hep.20503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srikureja W, Kyulo NL, Runyon BA, Hu KQ. MELD score is a better prognostic model than Child-Turcotte-Pugh score or Discriminant Function score in patients with alcoholic hepatitis. Journal of hepatology. 2005;42:700–706. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sheth M, Riggs M, Patel T. Utility of the Mayo End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score in assessing prognosis of patients with alcoholic hepatitis. BMC gastroenterology. 2002;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Verma S, Ajudia K, Mendler M, Redeker A. Prevalence of septic events, type 1 hepatorenal syndrome, and mortality in severe alcoholic hepatitis and utility of discriminant function and MELD score in predicting these adverse events. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2006;51:1637–1643. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9099-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.O'Shea RS, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, et al. AASLD practice guideline: alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2010;51:307–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.23258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Louvet A, Naveau S, Abdelnour M, et al. The Lille model: a new tool for therapeutic strategy in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis treated with steroids. Hepatology. 2007;45:1348–1354. doi: 10.1002/hep.21607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.