Abstract

Background

Although past research demonstrated that Medicaid expansions were associated with increased emergency department (ED) and primary care (PC) utilization, little is known about how long this increased utilization persists or whether post-coverage utilization is affected by prior insurance status.

Objectives

(1) To assess changes in ED, PC, mental and behavioral health care (MBHC), and specialty care visit rates among individuals gaining Medicaid over 24 months post-insurance gain; (2) To evaluate the association of previous insurance with utilization.

Methods

Using claims data, we conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of adults insured for 24 months following Oregon's 2008 Medicaid expansion. Utilization rates among 1,124 new and 1,587 returning enrollees were compared to those among 5,126 enrollees with continuous Medicaid coverage (≥1 year pre-expansion). Visit rates were adjusted for propensity score classes and geographic region.

Results

PC visit rates in both newly and returning insured individuals significantly exceeded those in the continuously insured in months four through 12, but were not significantly elevated in the second year. In contrast, ED utilization rates were significantly higher in returning insured compared to newly or continuously insured individuals and remained elevated over time. New visits to PC and specialist care were higher among those who gained Medicaid compared to the continuously insured throughout the study period.

Conclusions

Predicting the effect of insurance expansion on healthcare utilization should account for the prior coverage history of new enrollees. Additionally, utilization of outpatient services changes with time after insurance, so expansion evaluations should allow for rate stabilization.

Keywords: access to care, Medicaid, healthcare utilization, policy evaluation

Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) provided access to health insurance for millions of previously uninsured Americans,(1, 2) and many healthcare providers have seen the predicted early surge in demand for care.(3-5) Appropriate allocation and distribution of healthcare resources after insurance expansion requires prediction of long-term healthcare utilization patterns and a nuanced understanding of the healthcare needs of different groups of new enrollees. Because long-term data from the ACA are not yet available, past health insurance expansions can inform these predictions.(6-12)

Adults who gained coverage in 2008 Medicaid expansions in Wisconsin and Oregon increased their use of emergency (ED), primary care (PC) and specialist care after becoming insured.(10, 11, 13-15) While ED visit rates increased over time in Massachusetts following 2008 healthcare reform, the trend did not differ from the 3 years prior to reform.(16) While these earlier studies reported utilization rates for 12-15 months post-expansion, less is known about whether the increased utilization was constant over time. Some evidence suggests that more frequent transitions on and off Medicaid (known as ‘churn’) are associated with increased healthcare utilization rates.(17) Yet, previous research has not examined whether utilization for those who gained coverage differed from those who were already insured, nor have comparisons of post expansion temporal trends across a variety of healthcare settings been reported. Additionally, most prior studies of Medicaid expansions compared healthcare utilization in newly insured versus uninsured individuals.

To address these gaps in the literature, we conducted a retrospective cohort study of Medicaid-insured adults who were continuously insured for 24 months following the 2008 Oregon Medicaid expansion, determining the utilization rates of ED, PC, mental and behavioral health care (MBHC), and specialist care services over this time period. The Oregon Medicaid expansion (often called the ‘Oregon Experiment’) offered uninsured, low-income adults the opportunity to apply for Oregon Health Plan insurance [(OHP) Oregon's Medicaid Program]. Approximately 10,000 gained coverage from the 35,000 randomly selected to apply.(18)

We compared three groups: returning insured, newly insured, and continuously insured. We used a propensity score approach to adjust for differences between groups that were not related to their insurance history. We addressed the following questions: 1) what proportion of each group utilized the ED, PC, MBHC, or specialist care sites as their predominant site of care; 2) did those adults who gained Medicaid utilize more healthcare than those who were continuously insured; and if so, did utilization among those who gained coverage fall to rates similar to those in the continuously insured by 24 months after gaining coverage; and 3) among those who gained Medicaid coverage, did enrollees returning to Medicaid within three years of prior coverage have different patterns of healthcare utilization than new enrollees?

Methods

Study Design and Study Population

We used the official OHP Oregon Experiment registration list and OHP administrative enrollment data from 2005-2011 to identify adult (aged 18-64) Medicaid enrollees who obtained coverage through the Oregon Experiment and had no Medicaid coverage for ≥12 months prior to when they obtained OHP Standard. Within this group, we created two subgroups: (1) “returning insured”- had Medicaid coverage at some point in 2005-2006; and (2) “newly insured”- had no Medicaid coverage in that time period. We also selected a comparison group, (3) “continuously insured,” who had OHP Standard continuously for ≥12 months prior to the expansion and did not participate in the Oregon Experiment. The 24-month study period for returning and newly insured individuals began on the date each person gained coverage. Because there were eight random drawings in the Oregon experiment, insurance start dates varied in those gaining insurance. To avoid bias, study start dates were randomly assigned to individuals in the continuously insured group with the probability of the start date assignment based on the distribution of start dates in the newly and returning insured. For example, 11.4% of the patients who gained insurance following their selection from the registration list had coverage that started on March 11, 2008, so 11.4% of the continuously insured were assigned a start date of March 8, 2008. All groups were restricted to those who maintained OHP Standard coverage for their entire 24-month study period. This study was approved by the institutional review board at our institution.

Statistical Analysis

We used Medicaid claims data from 2008 through 2011 to measure the dependent variables: ED, PC, MBHC, and specialist care visit rates. We identified new and established patient visits using Evaluation and Management Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (Supplement, eTable 1). ED visits were categorized as related to mental health / alcohol / substance abuse, or not, based on a diagnosis-code driven algorithm developed by Billings et al.(19) Outpatient visits with psychiatric CPT codes were classified as MBHC. The remaining outpatient visits were categorized as PC, MBHC, or specialist care based on OHP provider classification lists (Supplement, eTable 2). The predominant source of care for a patient was defined by the most common setting and provider type for the patient's visits. In addition, PC and MBHC visits were sub-classified by location of care. The location of an outpatient visit was identified as a safety net clinic if the visit occurred at a public health clinic, Federally Qualified Health Center, Rural Health Center, Indian Health Service/tribal clinic, or Community Mental Health Center. Thus, visits to Community Mental Health Centers were classified as both MBHC and safety net.

The primary independent variable was insurance subgroup (newly, returning, or continuously insured). Because the insurance subgroups differed in multiple characteristics, a generalized propensity score approach was used to control for bias due to potential confounders.(20) Subjects were categorized into one of five mutually exclusive propensity classes based on their estimated probability for being returning or newly insured enrollees. See Supplement, Methods for additional details.

Adjusted utilization rates (visits per person per year) were calculated using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for within-subject correlation (21). Group*time was included as an interaction and propensity class, Primary Care Service Area (PCSA), distance to closest hospital and all patient characteristics with residual imbalance (χ2 p<0.05 within any class; sex, age, income, drug and alcohol dependency, and psychiatric disorders other than anxiety and depression) were included as covariates in all analyses to estimate adjusted rates. Additionally, three-way interactions between propensity class with group*time were included if statistically significant. The same GEE approach was used in the temporal analysis of changes in rates (visits per patient per 3 month interval) over time. We used a difference-in-differences approach(22) to examine temporal changes in PC and ED utilization within the two years post insurance gain, reporting quarterly utilization rates in returning and newly insured relative to those in the continuously insured group to control for temporal changes unrelated to insurance acquisition.

Results

Co-variate balance

Before implementing propensity class adjustment, the insurance groups differed on multiple characteristics (Table 1). The continuously insured included a higher percentage of women, adults with children enrolled in Medicaid, and individuals with hypertension and diabetes, compared to either the newly or returning insured. The returning insured were younger than the newly or continuously insured and had a higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, and drug and alcohol dependency. After developing propensity classes, balance improved for all covariates. Covariates that remained unbalanced in any propensity class were included in all analyses for additional control of confounding.

Table 1. Characteristics of Sample Groups.

| Prior to Propensity Class Implementation | After Propensity Class Implementation | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| % with Characteristic | p-value Within Propensity Classes1 | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Enrollee Insurance Status | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

|

New N=1124 |

Returning N=1587 |

Continuous N=5126 |

p-value X2 |

1 N=1961 |

2 N=1689 |

3 N=1233 |

4 N=1239 |

5 N=1715 |

||

| Sex: Female | 47.5 | 53.0 | 60.0 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.02 | 0.09 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Age Category | Less than 30 | 15.3 | 14.6 | 14.5 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.51 | 0.86 | 0.01 |

| 30 to <50 | 46.3 | 54.8 | 45.9 | |||||||

| 50 to 65 | 38.4 | 30.6 | 39.6 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.5 | 0.109 | 0.34 | 0.86 | 0.46 | 0.89 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 84.3 | 84.8 | 83.0 | |||||||

| Other minority | 8.8 | 9.1 | 11.1 | |||||||

| Unknown | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Child on Case | 12.2 | 17.6 | 22.5 | <0.001 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.85 | 0.45 | 0.18 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Income (%FPL) | less than 10% | 53.0 | 52.2 | 44.7 | <0.001 | 0.25 | 0.68 | 0.83 | 0.02 | 0.752 |

| 10% to less than 50% | 19.0 | 18.8 | 19.8 | |||||||

| 50% to less than 65% | 7.9 | 7.5 | 11.0 | |||||||

| 65% to less than 85% | 10.1 | 12.4 | 13.9 | |||||||

| 85% to less than 100% | 9.9 | 9.1 | 10.6 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Rural zipcodeb | 42.8 | 46.5 | 42.5 | 0.019 | 0.09 | 0.80 | 0.19 | 0.29 | 0.07 | |

|

| ||||||||||

| Nearest hospitalc | More than 10 miles | 18.3 | 19.3 | 16.8 | 0.151 | 0.23 | 0.81 | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.43 |

|

| ||||||||||

| Chronic Condition | Hypertension | 36.5 | 35.9 | 37.4 | 0.505 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| Diabetes | 13.8 | 13.7 | 16.7 | 0.003 | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.48 | 0.86 | 0.69 | |

| Heart Disease | 11.4 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 0.546 | 0.29 | 0.47 | 0.09 | 0.95 | 0.65 | |

| Obstructive Pulmonary Disease | 17.4 | 23.3 | 20.1 | 0.001 | 0.83 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.57 | 0.42 | |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | 20.8 | 24.6 | 20.2 | 0.001 | 0.97 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.59 | 0.26 | |

| Anxiety | 21.2 | 25.0 | 22.0 | 0.024 | 0.61 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.40 | 0.75 | |

| Depression | 27.8 | 31.1 | 25.9 | <0.001 | 0.09 | 0.28 | 0.85 | 0.86 | 0.94 | |

| Other psychiatric disorder | 22.4 | 26.0 | 22.3 | 0.008 | 0.35 | 0.78 | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.56 | |

| Drug dependency | 8.4 | 16.4 | 10.7 | <0.001 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.49 | 0.03 | |

| Alcohol dependency | 12.9 | 17.3 | 8.9 | <0.001 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.08 | <0.01 | |

Bold face indicates residual imbalance (p<.05) within propensity classes.

Propensity classes were created to adjust for the between group difference in covariates. To do this, propensity scores for membership in the newly insured and returning insured groups were generated from a multinomial regression of group membership on patient covariates. Propensity scores were categorized as: 1) low probability of being either newly or returning insured, 2) moderate probability of being either, 3) high probability of being newly insured and low probability of returning insured, 4) low probability of being newly insured and high probability of returning insured, and 5) high probability of being either. Details of the propensity class categorization are given in eMethods in the Supplement. Variables with residual imbalance were included with propensity class as covariates in all analyses.

Based on classification by the Oregon Office of Rural health

Based on the centroid of the patient's zip code

P-value(χ2): χ2 test of between group difference

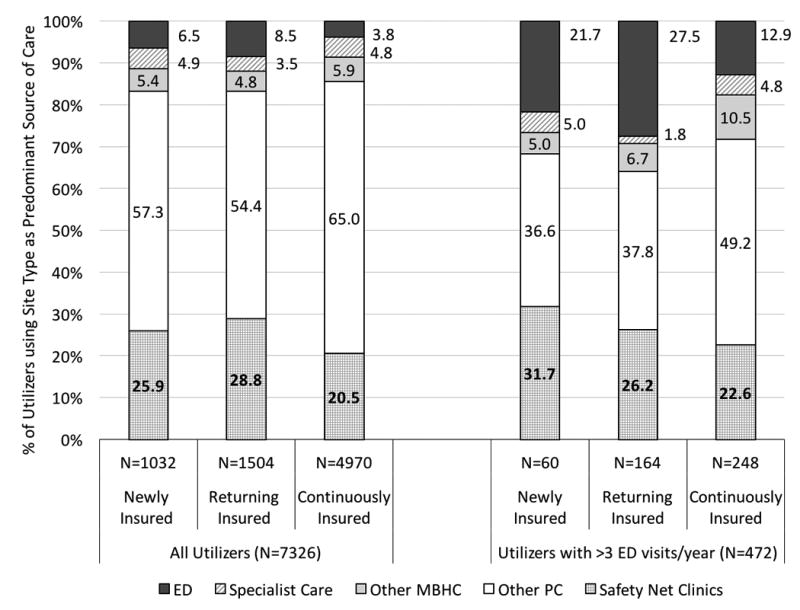

Predominant Site of Care

Overall, 6.5% of Medicaid enrollees had no utilization in the study period: 8.2% among newly insured, 5.2% among returning insured and 6.6% among continuously insured. Of those with any utilization, over 91% used outpatient care rather than the ED as their predominant source of care (Figure 1). Most patients (including those with the highest ED utilization (>3 ED visits/year) predominantly used outpatient PC clinics, and ≥20% of all three groups relied primarily on the safety net. A larger percentage of the returning insured (8.5%) and newly insured (6.5%) predominantly used the ED, compared to the continuously insured (3.8%) (p<0.002).

Figure 1.

Predominant Site of Healthcare for all Utilizers and Utilizers with more than 3 Emergency Department Visits per Year; Notes: ED: Emergency Department; Safety Net Clinic: Rural Health Center, Federally Qualified Health Center, Indian Health Service/Tribal Clinic, Public Clinic or Community Mental Health Center; Other Outpatient: Primary Care, Specialist Care or Mental/Behavioral Health Care visits that did not occur at a Safety Net Clinic.

Yearly Utilization Rates

Table 2 compares the adjusted utilization rates in the three insurance groups in years 1 and 2 of the study period. In both years, ED visits that did not result in an inpatient admission were significantly higher in the returning insured (mean= 0.7 visits/patient/year) than in the newly or continuously insured (mean ranged from 0.47 to 0.54 visits/patient/year). There were no significant differences between the first and second year within any of the groups. Adjusted mental and behavioral health related ED visit rates did not differ significantly between groups.

Table 2. Healthcare Utilization in the First Two Years after the Oregon Experiment.

| Year 1, visits per patient per year (95% CI)a | Year 2, visits per patient per year (95% CI)a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Enrollee Insurance Status | Insurance Group | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Type of Utilization | New | Returning | Continuous | New | Returning | Continuous |

| Emergency Departmentb | 0.49* (0.43 - 0.56) |

0.68*ǂ (0.61 - 0.76) |

0.47 (0.44 - 0.51) |

0.54 (0.47 - 0.62) |

0.66*ǂ (0.60 - 0.73) |

0.49 (0.46 - 0.53) |

| Mental/Behavioral Health Care relatedc |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.02) |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.01) |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.01) |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.02) |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.02) |

0.01 (0.01 – 0.01) |

| Not Mental/Behavioral Health Care relatedc |

0.47* (0.41 – 0.55) |

0.67*ǂ (0.61 – 0.75) |

0.45 (0.42 – 0.49) |

0.51* (0.45 – 0.58) |

0.65*ǂ (0.58 – 0.72) |

0.47 (0.44 – 0.51) |

|

| ||||||

| Outpatient Care: | ||||||

| Primary Cared | 4.02 (3.79 – 4.26) |

3.97 (3.79 – 4.17) |

3.92 (3.81 – 4.04) |

4.21 (3.97 - 4.45) |

4.28▪ (4.08 - 4.50) |

4.11▪ (4.00 – 4.22) |

| Mental/Behavioral Health Caree | 0.28 (0.21 - 0.37) |

0.23ǂ (0.18 - 0.29) |

0.34 (0.29 - 0.40) |

0.44▪ (0.34 - 0.58) |

0.36▪ (0.29 - 0.44) |

0.35 (0.30-0.42) |

| Specialist Caref | 0.56 (0.49 - 0.64) |

0.54 (0.48 - 0.61) |

0.61 (0.57 - 0.65) |

0.84ǂ▪ (0.74 - 0.96) |

0.79▪ (0.71 - 0.88) |

0.72▪ (0.67 - 0.76) |

|

| ||||||

| Outpatient Safety Net Careg: | ||||||

| Primary Cared | 0.86ǂ (0.75 – 0.98) |

1.00ǂ (0.84 - 1.03) |

0.66 (0.61 - 0.71) |

1.23ǂ▪ (1.10 - 1.39) |

1.31ǂ▪ (1.19 - 1.44) |

0.97▪ (0.91 – 1.04) |

| Mental/Behavioral Health Caree | 0.07 (0.05 - 0.11) |

0.06 (0.04 - 0.09) |

0.07 (0.05 – 0.09) |

0.10 (0.07 – 0.16) |

0.10▪ (0.07 - 0.14) |

0.07 (0.06 - 0.10) |

|

| ||||||

| New Patient Visitsg: | ||||||

| Primary Cared | 0.53*ǂ (0.50 - 0.58) |

0.48*ǂ (0.45 -0 .52) |

0.14 (0.13 - 0.15) |

0.22ǂ▪ (0.20 - 0.26) |

0.23ǂ▪ (0.20 - 0.25) |

0.14 (0.13 - 0.15) |

| Specialist Caref | 0.13*ǂ (0.11 - 0.16) |

0.10*ǂ (0.09 - 0.12) |

0.07 (0.06 - 0.08) |

0.17ǂ▪ (0.15 - 0.20) |

0.19ǂ▪ (0.16 - 0.21) |

0.13▪ (0.12 - 0.14) |

|

| ||||||

| Inpatient Utilization: | ||||||

| Inpatient Stays | 0.05 (0.03 - 0.07) |

0.06ǂ (0.04 - 0.07) |

0.04 (0.03 - 0.05) |

0.06 (0.04 – 0.08) |

0.06 (0.05 - 0.08) |

0.05 (0.04 – 0.06) |

| Inpatient Days | 0.23ǂ (0.15 - 0.33) |

0.15 (0.11 - 0.21) |

0.15 (0.12 - 0.18) |

0.26 (0.17 - 0.40) |

0.19 (0.14 - 0.25) |

0.18 (0.15 - 0.22) |

| Admissions from Emergency Department | 0.024 (0.017 - 0.035) |

0.023 (0.017 - 0.033) |

0.024 (0.020- 0.028) |

0.038 (0.027 - 0.054) |

0.036▪ (0.027 - 0.047) |

0.029▪ (0.025 - 0.035) |

Visits per patient per year estimated by Poisson regression using generalized estimating equations and adjusted for propensity class, sex, age, income, Primary Care Service Area, distance to nearest hospital, psychological disorders other than depression, and anxiety and alcohol and drug dependency. Details of the regression analyses are given in the Supplement.

Excludes Emergency Department visits admitted to inpatient.

Emergency Department visits were classified as mental health, or alcohol or drug abuse related using the method reported by Billings et al.(19)

Visit provider was a primary care clinician, or a nurse practitioner, physician's assistant, physician with no listed specialty, physician with a listed specialties of Primary Care or Family Practice, or an Internist, Obstetricians, Gynecologist, Pediatrician, Geriatric or Adolescent Medicine Practitioner without an additional listed clinical sub-specialty.

Visit provider was a psychiatrist or was classified by Oregon Medicaid claims as a mental health provider or clinic.

Visit provider was a Specialty Clinic or a physician with a listed clinical sub-specialty who did not also list Family Practice or Primary Care as a specialty

Billing provider was a Rural Health Center, Federally Qualified Health Center, Indian Health Service/Tribal Clinic, Public Clinic or Community Mental Health Center. These visits are subsets of total Primary Care and MBHC visits.

New patient visits were identified by Evaluation and Management codes.

Significant difference from continuously insured within year.

Significant difference between New and Returning Insured within year

Significant within group difference between years

The PC visit rate ranged from 3.9 to 4.3 visits per year. Total PC visit rates did not differ between groups in either year. In contrast, in year 1, new patient PC visits were higher in newly insured than in both returning and continuously insured groups, and higher among returning insured persons than among the continuously insured. New patient PC rates dropped significantly in year 2, but remained significantly higher in the both groups compared to the continuously insured. Safety net PC rates which ranged from 0.7 to 1.0 visits/patient/year, were higher in returning and newly insured than in continuously insured in year 1; they increased significantly in all three groups in year 2, (ranging from 1.0 to 1.3 visits/patient/year), remaining higher in the returning and newly than the continuously insured.

MBHC visit rates ranged from 0.23 to 0.34 visits/patient/year in year 1 and from 0.35 to 0.44 visits/patient/year in year 2. Rates were lower in returning than in continuously insured persons in year 1, while the rates in newly insured were not significantly different from either returning or continuously insured. Total MBHC rates rose significantly between years 1 and 2 in both returning and newly insured, but did not change significantly in the continuously insured.

Total specialist care visit rates ranged from 0.5 to 0.6 visits/patient/year in year 1 and did not differ significantly between groups. Specialist rates rose significantly in all groups in year 2, with a range from 0.7 to 0.8 visits/patient/year; rates in the newly insured remained significantly higher than in the continuously insured in year 2. New patient specialist care visit rates (which averaged 0.1 visits/patient/year) were higher in the newly and returning insured compared to the continuously insured group in year 1. New patient specialist care visit rates increased significantly in all groups in year 2 (where they ranged from 0.13 to 0.19 visits/patient/year), and the rates among newly and returning insured persons remained significantly higher than the continuously insured.

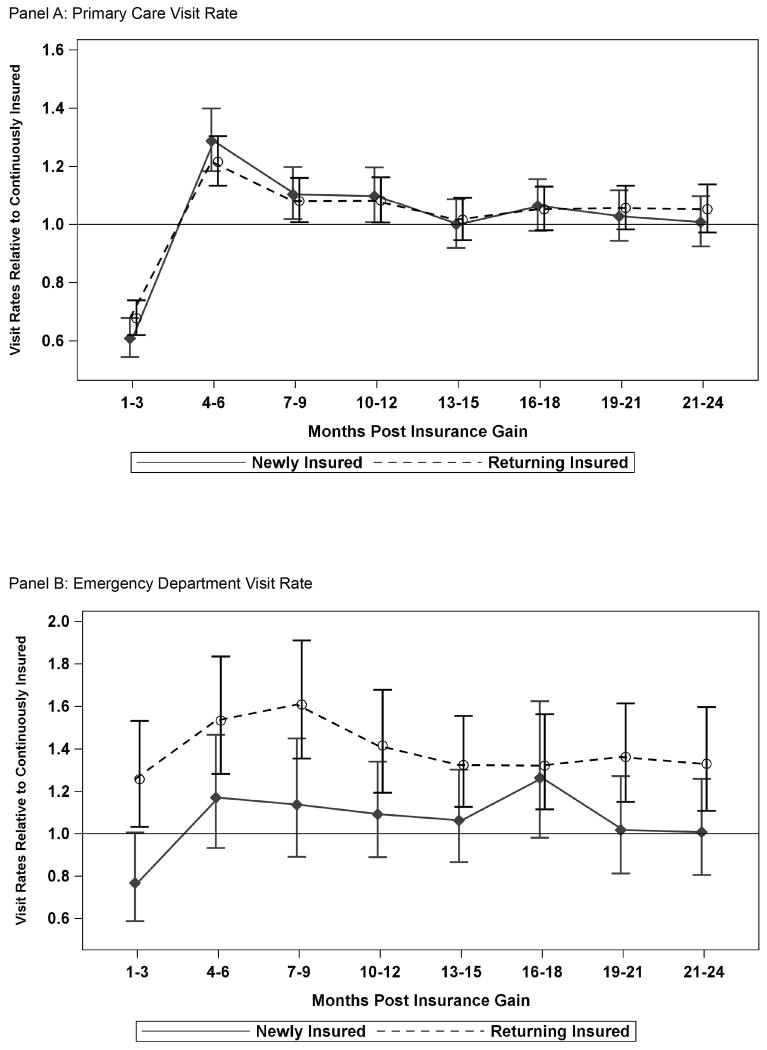

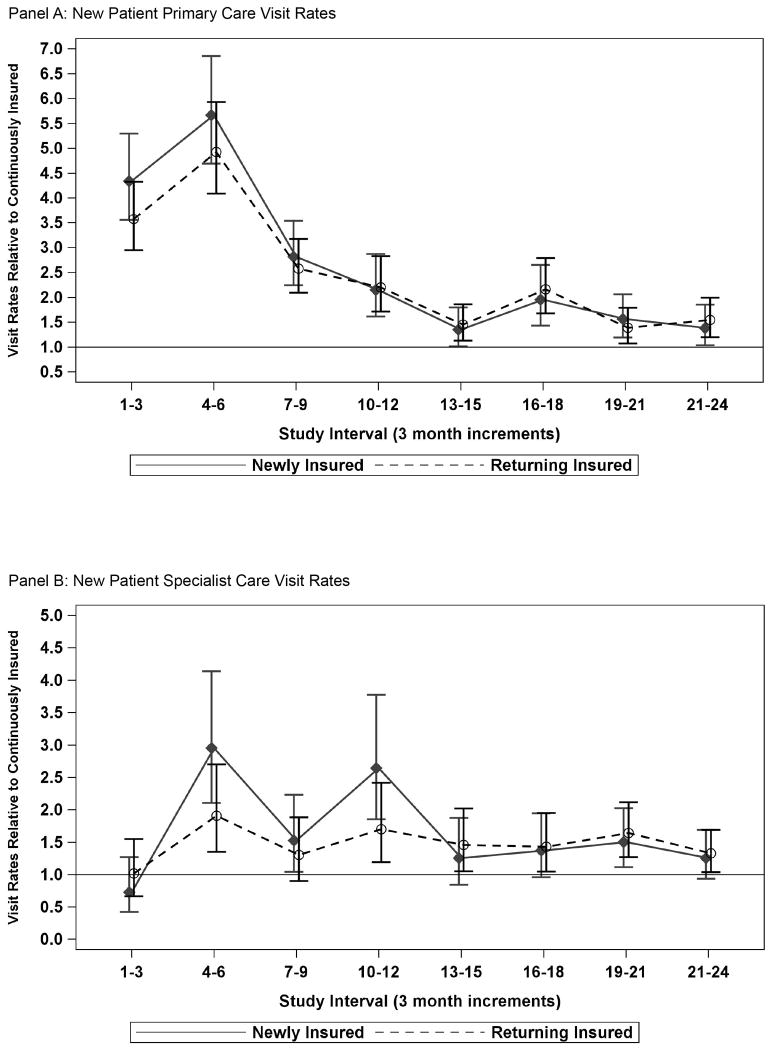

Three Month Utilization Rate Ratios

Figures 2 and 3 display temporal patterns of adjusted utilization rate ratios for 3 month intervals, which are more sensitive to changes over time than total yearly rates. Results are presented as rates relative to those in the continuously insured.

Figure 2.

Temporal Patterns of Relative Rates of Emergency Department and Primary Care Utilization (Returning and Newly Insured vs. Continuously Insured); Notes: Rates were estimated by GEE Poisson Regression and adjusted for propensity class, sex, age, income, Primary Care Service Area, distance to nearest hospital, psychological disorders other than depression and anxiety, and alcohol and drug dependency. Rates in newly and returning insured are presented relative to rates in continuously insured to control for temporal trends in utilization that were unrelated to time on insurance. Additional graphs of the temporal patterns of MBHC and total specialist care visit rates are provided in the Supplement.

Figure 3.

Temporal Patterns of New Patient Visit Rates in Returning and Newly Insured Relative to Continuously Insured Enrollees; Notes: Rates were estimated by GEE Poisson Regression and adjusted for propensity class, sex, age, income, Primary Care Service Area, distance to nearest hospital, psychological disorders other than depression and anxiety, and alcohol and drug dependency. Rates in newly and returning insured are presented relative to rates in continuously insured to control for temporal trends in utilization that were unrelated to time on insurance.

Total visit rates

ED visit rates among the returning insured were significantly higher than among the continuously insured in all time periods. Adjusted total PC rate ratios show that both returning and newly insured had higher utilization than the continuously insured; these increased rates started 3 months after coverage gain and did not fall to the level of the continuously insured until after 12 months. Both newly and returning insured groups started with total PC visit rates significantly lower than the continuously insured in the first 3 months post-coverage: adjusted rate ratio (adjRR) 0.68 (95% CI 0.62-0.74) for returning and 0.61 (95% CI 0.54-0.68) for newly insured (Figure 2, Panel A). By months 4-6 adjusted PC rate ratios for these groups increased sharply, surpassing those of the continuously insured: adjRR 1.22 (95% CI 1.13-1.30) for returning and 1.29 (95% CI 1.18-1.40) for newly insured. Rates in both the newly and returning insured groups were not significantly different from the continuously insured by months 13-15.

ED visit rates changed little over time, differed substantially between returning and newly insured, and were similar between the newly and continuously insured (Figure 2, Panel B). Although ED visit rates among the newly insured were not significantly different from the continuously insured in the study period, ED visit rates among the returning insured were significantly higher than the continuously insured in all 24 months. MBHC and specialist care rate ratios are presented in Supplement, eFigures 1 and 2.

New patient visit rates

New patient PC visits rates were significantly higher among the newly and returning insured compared to the continuously insured throughout the study period: adjRR=4.34 (95% CI 3.55-5.30) in months 1-3, 5.67 (95% CI 4.69-6.85) in months 4-6, and 1.38 (95% CI 1.03-1.85) in months 22-24 for newly relative to continuously insured (Figure 3, Panel A). The corresponding rate ratios for returning relative to continuously insured were 3.57 (95% CI 2.95-4.33) in the first 3 months, 4.93 (95% CI 4.09-5.93) in months 4-6 and 1.38 (95% CI 1.03-1.85) in months 22-24. There were no significant differences in new patient PC rates between returning and newly insured.

Newly insured enrollees had significantly higher new patient specialist care rates than continuously insured from months 4-12, (Figure 3, Panel B), with the highest adjusted rate ratios occurring at 4-6 months and 9-12 months after insurance gain. New patient specialist care rates were also elevated in returning insured relative to continuously insured from 4 months through the end of the study, but the difference in the 6-9 month interval was not statistically significant. The difference in new patient specialist visits was not significant between returning and newly insured at any time point.

Discussion

Our research complements prior analyses using the Oregon Experiment data as it studies only those who actually gained coverage in the Oregon Experiment, and examines changes in this subpopulation's utilization of multiple types of healthcare services over time. Specifically, we compared the differences between new and returning Medicaid enrollees, assessed changes in utilization patterns over time rather than total utilization, and investigated the use of safety net services. In addition, our comparison of distinct cohorts determined by insurance history prior to re-enrollment was not feasible in prior studies focused solely on the Oregon Experiment's randomized design. While studies focused on randomization allow for inference of causality, our observational study provides insights into the likely results of Medicaid expansion post-ACA, given the differences between those who apply for insurance and random samples of the uninsured.

Our first key finding is that returning and newly insured individuals differed markedly in their post-coverage ED utilization. The returning insured utilized the ED at significantly higher rates than newly and continuously insured; patterns among the newly insured were similar to the continuously insured (Figure 2). Although utilization rates were adjusted for differences in the probability of being in the returning insured group and unbalanced covariates, these findings suggest that severity of illness and likelihood of chronic disease complications may differ between subgroups obtaining Medicaid coverage after an expansion. Those returning to Medicaid after churning off coverage may inherently have higher levels of medical, behavioral and social complexity that also put them at higher risk for coverage instability. This difference highlights the need to account for patients' past insurance patterns when assessing the impact of policy changes on utilization. Accounting for past insurance is particularly important when assessing ED utilization after a Medicaid expansion to distinguish between ED use attributable to the policy change and ED use by patients emerging from insurance churn. Thus, prediction of healthcare demand following an expansion will require evaluating the expected proportion of new versus returning enrollees.

Second, our study was able to follow patients for a longer period of time than previous studies. We observed that after an initial surge, total PC utilization rates in returning and newly insured dropped to levels comparable to rates in the continuously insured. This suggests the need for follow-up periods longer than 12 months when assessing policy change impacts on PC utilization. It is also notable that the rate at which returning and newly insured patients saw new PC providers remained higher than rates among the continuously insured two years after insurance gain, indicating that it may take some patients a long time to establish a medical home after ACA expansions, as suggested by prior studies showing that while health insurance coverage improves access to PC, patients gaining new Medicaid still struggle to find providers.(23-26) It is likely that patients already established in a PC medical home increased utilization shortly after gaining Medicaid, as shown by Angier et al,(3) in a similar population. Patients without a PC medical home may take longer to get established (18, 23) and PC providers should prepare for increased new patient visit demand to continue after ACA expansions.

It was notable that Medicaid patients in this study predominantly used outpatient care, not the ED. Even those with high ED utilization (>3 visits per year on average) did not predominantly use the ED. This finding substantiates other research showing that most frequent ED users are high utilizers of multiple sources of healthcare, with ED use accounting for a small proportion of their total utilization.(27, 28) We also discovered that over 20% of enrollees who sought outpatient care used safety net clinics, and this proportion increased over time in all groups. This finding is consistent with the national trend of increased utilization of safety net clinics among Medicaid-insured patients(29) and confirms prior findings that patients do not leave safety net settings once they gain insurance coverage; instead, demand for safety net services increases.(3, 11, 15)

Examining multiple types of outpatient care over time, we also observed that the timing of and peak demand for different types of services were variable: PC utilization rates for returning and newly insured were higher than the continuously insured in months 4 through 12; MBHC and specialist care visit rates did not increase significantly until after 12 months in both returning and newly insured; utilization rates of new patient PC and specialist services among those who gained coverage were much higher than in the continuously insured in the first year after insurance gain and remained higher than utilization rates among the continuously insured at 24 months. These findings imply that demand for some services likely peaked immediately after ACA expansions; however, it may take time for individuals to find PC medical homes and fulfill other pent-up healthcare needs, such as those for MBHC and specialist care. Thus, the effects of the ACA that require stable utilization of and consistent access to healthcare services may not be observable for some time.

There are limitations to our study

Our population was limited to individuals who sought and maintained Medicaid coverage through the Oregon Experiment; healthcare utilization may differ in states with different PC or safety net resources. We used propensity scores to create subgroups that were more homogeneous with respect to potential confounders; however, residual unobserved differences may exist that could have affected utilization patterns within groups differentially. Additionally, the patients in all three groups voluntarily sought coverage, and thus may differ from persons who gain coverage due to an insurance mandate. The use of claims data prevented comparisons with utilization rates in the uninsured, but allowed us to identify continuously insured persons as a comparison group. We did not assess healthcare utilization or baseline health prior to enrollment, as these data were only available for the continuously insured. Our data were insufficient to examine the causes of insurance instability in the returning insured and whether the association of post insurance utilization rates varied by the cause of churning: it would be of interest to look into these issues in future studies.

Conclusions

Individuals who gained Oregon Medicaid increased utilization of PC within the first year post-coverage; in the second year, PC utilization stabilized to rates similar to those who were continuously insured. In contrast, increases in MBHC and specialist care visit rates were only apparent during the second year after gaining coverage. These findings emphasize the need to examine long-term utilization before drawing conclusions about the impact of Medicaid expansions. Further, changes in health outcomes may be visible only after patients have been appropriately connected to these needed services. Individuals returning to Medicaid coverage utilized care significantly differently than those gaining new coverage. Most notably, the returning insured had significantly higher rates of ED utilization than the newly insured, suggesting that predictions about and evaluations of the healthcare impact of future Medicaid expansions should take into account new enrollees' prior insurance history. Regardless of insurance history, the majority of Medicaid enrollees in this study utilized PC as their predominant source of care, and a substantial portion of their PC utilization was in safety net clinics. This demonstrates the paramount importance of adequate primary care infrastructures in the era of post-ACA Medicaid expansion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant R01HL107647 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, K23DA037453 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, K08 HS021 522 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine. None of the funders were part of the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Jean O'Malley had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data. Additional Contributions: We thank the Oregon Health Authority for providing the Medicaid data used in this analysis, Emerson Ong at the Oregon Office of Rural Health for providing files linking Oregon zip codes to Primary Care Service Areas, and Carrie Tillotson, MPH from OCHIN for providing assistance with the figures.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. Summary of the Affordable Care Act. Menlo Park, C.A.: 2013. Contract No.: 806-02. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation. How is the ACA Impacting Medicaid Enrollment? Menlo Park, C.A.: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angier H, Hoopes M, Gold R, et al. An early look at rates of uninsured safety net clinic visits after the Affordable Care Act. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):10–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser Family Foundation, Commonwealth Fund. Experiences and Attitudes of Primary Care Providers Under the First Year of ACA Coverage Expansion: Findings from the Kaiser Family Foundation/Commonwealth Fund 2015 National Survey of Primary Care Providers. Washington, D.C.: 2015. Contract No.: 1823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marketing General Incorporated. 2015 ACEP Poll Affordable Care Act Research Results. Alexandria, V.A.: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisman R. Health care policy. Straining emergency rooms by expanding health insurance. Science. 2014;343(6168):252–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1249341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Medford-Davis LN, Eswaran V, Rohan M, et al. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Effect on Emergency Medicine: A Synthesis of the Data Ann Emerg Med 2015; May 11 [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buchmueller TC, Grumbach K, Kronick R, et al. The effect of health insurance on medical care utilization and implications for insurance expansion: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(1):3–30. doi: 10.1177/1077558704271718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen H, Baicker K, Finkelstein A, et al. What the Oregon health study can tell us about expanding Medicaid. Health Aff. 2010;29(8):1498–506. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finkelstein A, Taubman S, Wright B, et al. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment: Evidence from the First Year. Q J Econ. 2012;127(3):1057–106. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjs020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVoe JE, Marino M, Gold R, et al. Community Health Center Use After Oregon's Randomized Medicaid Experiment. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(4):312–20. doi: 10.1370/afm.1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hanchate AD, Lasser KE, Kapoor A, et al. Massachusetts reform and disparities in inpatient care utilization. Med Care. 2012;50(7):569–77. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824e319f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeLeire T, Dague L, Leininger L, et al. Wisconsin Experience Indicates That Expanding Public Insurance To Low-Income Childless Adults Has Health Care Impacts. Health Aff. 2013;32(6):1037–45. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taubman SL, Allen HL, Wright BJ, et al. Medicaid increases emergency-department use: evidence from Oregon's Health Insurance Experiment. Science. 2014;343(6168):263–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1246183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold R, Bailey SR, O'Malley JP, et al. Estimating demand for care after a medicaid expansion: lessons from Oregon. J Ambul Care Manage. 2014;37(4):282–92. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C, Scheffler G, Chandra A. Massachusetts Health Care Reform and Emergency Department Utilization. New Englad Journal of Medicine. 2011 Sep 7;:365–e25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1109273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Banerjee R, Ziegenfuss JY, Shah ND. Impact of discontinuity in health insurance on resource utilization. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:195. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health Policy Brief. The Oregon Health Insurance Experiment. Health Aff. 2015 Jul 16; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings J, Parikh N, Mijanovich T. Emergency Department Use in New York City: A Substitute for Primary Care? Washington, D.C.; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai K, Van Dyk D. Causal Inference with General Treatment Regimes: Generalizing the Propensity Score. Am Stat Assoc. 2004;99(467):854–66. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardin JW, Hilbe JM. Generalized Estimating Equations. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How Much Should We Trust Differences-in-Differences Estimates? The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2004;119(1):249–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allen H, Wright BJ, Baicker K. New medicaid enrollees in Oregon report health care successes and challenges. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(2):292–9. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richman IB, Clark S, Sullivan AF, et al. National study of the relation of primary care shortages to emergency department utilization. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(3):279–82. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hing E, Decker SL, Jamoom E. Acceptance of New Patients With Public and Private Insurance by Office-based Physicians: United States, 2013. Hyattsville: p. MD2015. Contract No.: 195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heintzman J, Gold R, Bailey SR, et al. The Oregon experiment re-examined: the need to bolster primary care. BMJ. 2014;349:g5976. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Billings J, Raven MC. Dispelling an urban legend: frequent emergency department users have substantial burden of disease. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(12):2099–108. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt KA, Weber EJ, Showstack JA, et al. Characteristics of frequent users of emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shin P, Sharac J, Rosenbaum S. Community Health Centers And Medicaid At 50: An Enduring Relationship Essential For Health System Transformation. Health Aff. 2015;34(7):1096–104. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.