Abstract

Angiosarcoma of the lower urinary tract is exceedingly rare. A minority of cases are associated with local radiotherapy. Epithelioid angiosarcoma is a variant of angiosarcoma composed of large rounded epithelioid endothelial cells that are positive for cytokeratin on immunostaining. There are only two cases of post-radiation epithelioid angiosarcoma reported in the urinary bladder, and none in the prostate gland. We report a case of epithelioid angiosarcoma involving the urinary bladder and prostate in a patient with a history of radiotherapy for prostatic adenocarcinoma. A brief review of literature regarding post-radiation epithelioid angiosarcomas in the lower urinary tract is discussed.

Introduction

Angiosarcoma of the lower urinary tract is exceedingly rare. In the urinary bladder, only 34 cases have been reported in the English literature, 13 of which were associated with local radiation therapy.1–6 There are only 14 reported cases of angiosarcoma of the prostate, five of which were associated with radiation therapy.7–13

Epithelioid angiosarcoma is a variant of angiosarcoma composed of large rounded epithelioid endothelial cells that are positive for cytokeratin on immunostaining.14 There are 12 reported cases of epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder, only two of which were associated with previous radiation.2,6,15,16 To the best of our knowledge, epithelioid angiosarcoma of the prostate gland has not been previously reported. It is important to be aware of epithelioid angiosarcoma, as its histologic appearance and positive cytokeratin immunostain may mimic a poorly differentiated carcinoma.14

We report a case of epithelioid angiosarcoma involving the urinary bladder and prostate in a patient with a history of external beam radiation for prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Case report

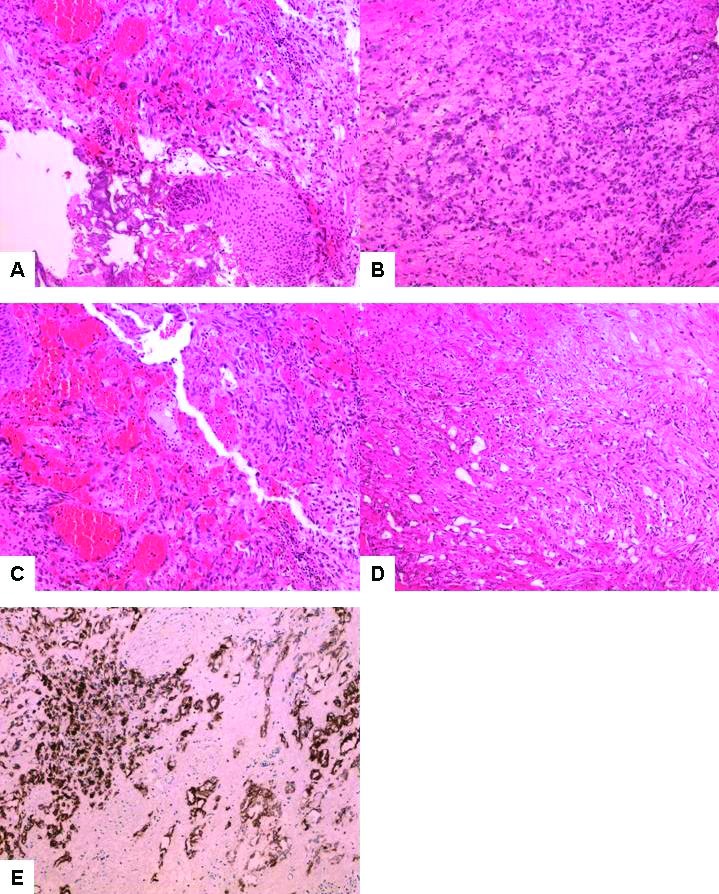

A 79-year-old man was treated in 2007 with external beam radiotherapy for prostatic adenocarcinoma. In the spring of 2013, he developed irritative lower urinary tract symptoms and gross hematuria. Cystoscopy revealed a papillary bladder tumour, which was resected transurethrally. Microscopically, a widely infiltrating, poorly-differentiated neoplasm was identified (Fig. 1A). The tumour had epithelioid cytologic features (Fig. 1B), with areas of hemorrhage and spindle cell patterns (Figs. 1C, 1D). The findings were considered to be in keeping with a high-grade urothelial carcinoma with sarcomatoid dedifferentiation. Some of the curetted surfaces contained proliferative urothelial epithelium with a reactive polypoid/papillary hyperplasia (Fig. 1A) that had the potential to be misinterpreted as a noninvasive papillary component of urothelial carcinoma. The immunostain for cytokeratin 7 was positive in the majority of the tumour cells (Fig. 1E). The tumour cells were negative for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) and Pap on immunostaining. The cytokeratin 20 immunostain was positive in the surface urothelium and negative in the tumour cells.

Fig.1.

(A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the original biopsy from cystoscopy showing a poorly differentiated, widely infiltrating neoplasm. Some of the curetted surfaces contain reactive urothelium (10X); (B) In most areas, the tumour had epithelioid cytologic features (10X); (C) Tumour with hemorrhagic changes (10X); (D) Tumour with spindle cell pattern (10X); (E) The immunostain for cytokeratin 7 is positive in the majority of the tumour cells (10X).

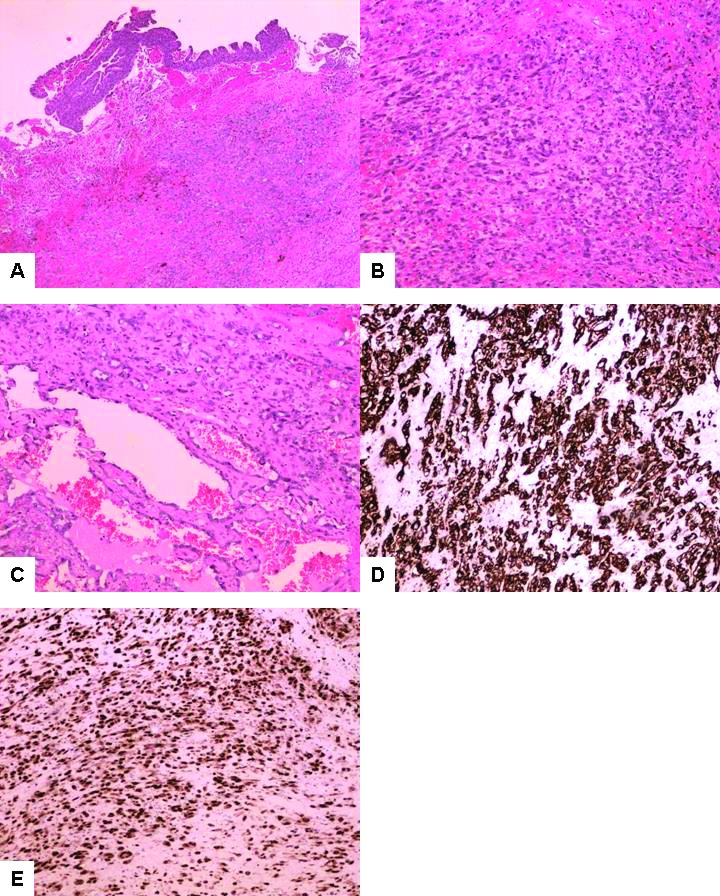

Two months following the transurethral curettage, the patient underwent radical cystoprostatectomy. Microscopic examination demonstrated an extensively invasive, high-grade neoplasm involving the prostate gland, both seminal vesicles, and bladder trigone. Multiple resection margins of the prostate and bladder wall were involved by invasive tumour. The malignancy showed a range of morphologic appearances, with some areas of solid and epithelioid pattern resembling a poorly differentiated carcinoma and other areas showing more pronounced vascular differentiation with anastomosing, angular, blood-filled spaces lined by elongated hyperchromatic tumour cells (Figs. 2A, 2B, 2C). Immunohistochemical stains showed expression of vascular markers CD31 (Fig. 2D), CD34, FLI1, and ERG (Fig. 2E) in the tumour cells. The tumour cells showed patchy positivity for cytokeratin 7. Both the prostate and bladder tumour component showed 20‒60% of nuclear staining for c-Myc (Figs. 3A, 3B). The pelvic/celiac lymph node dissection showed one of 34 lymph nodes positive for metastatic tumour with extranodal tumour extension.

Fig. 2.

(A) Microscopic examination of the cystoprostatectomy specimen demonstrates an extensively invasive, high-grade neoplasm in the urinary bladder (4X); (B) Several areas show a poorly differentiated epithelioid malignancy resembling a poorly differentiated carcinoma (10X); (C) Tumour with more pronounced vascular differentiation, with anastomosing, angular, blood-filled spaces lined by elongated hyperchromatic atypical cells (10X); (D) Immunohistochemical stains show strong and diffuse cytoplasmic expression of CD31 in the tumour cells (10X); (E) Immunohistochemical stains show strong nuclear expression of ERG in the tumour cells (10X).

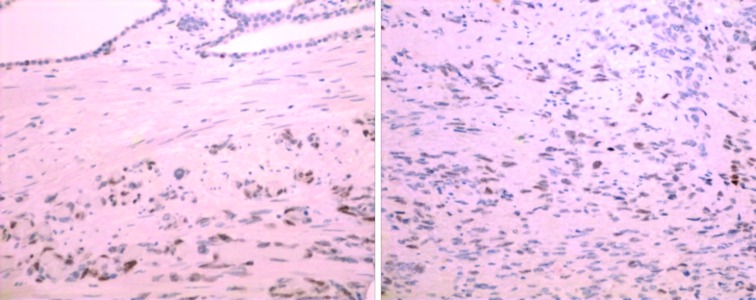

Fig. 3.

(A) Immunohistochemistry for c-Myc protein expression in the tumour cells in the prostate gland (10X); (B) Immunohistochemistry for c-Myc protein expression in the tumour cells in urinary bladder (10X).

The overlying bladder mucosa showed reactive papillary hyperplasia with no evidence of urothelial malignancy. A tiny residual focus of prostatic adenocarcinoma was found within the prostate gland peripheral zone with perineural invasion.

Retrospective review of the hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slides from the previous transurethral curettage showed areas of the tumour with a vasoformative pattern similar to that identified in the cystoprostatectomy specimen. A diagnosis of epithelioid angiosarcoma involving the urinary bladder and prostate gland was made.

The patient’s postoperative recovery was complicated by a pelvic abscess with concomitant osteomyelitis. He had had prior radiation and was considered too frail for adjuvant chemotherapy so no further therapy was provided. He is currently alive without evidence of disease 20 months after cystoprostatectomy.

Discussion

The diagnostic criteria for radiation-induced sarcomas were described as: a previous history of radiotherapy with a latency period of more than three years and development of histologically confirmed sarcoma within a previously irradiated field.17,18 The present case satisfies all of the criteria for the radiation-induced angiosarcoma. The extensive involvement of both the prostate gland and inferior bladder wall made it difficult to determine the exact primary site of origin.

Awareness of the histopathologic spectrum of angiosarcoma is important for the correct diagnosis, especially when dealing with small biopsy specimens. An angiosarcoma with predominant epithelioid features and solid patterns may lead to the erroneous diagnosis of a poorly differentiated carcinoma, as occurred in the current case. The urothelium may show significant post-radiation atypia, or may be reactive to the underlying malignancy and be incorrectly interpreted. A positive cytokeratin immunostain in the invasive tumour cells, if performed alone, will further contribute to misinterpretation of an epithelioid angiosarcoma as a carcinoma.

The most useful morphological characteristics to raise one’s suspicion of an angiosarcoma are the presence of blood-filled spaces of variable size and shape lined by atypical cells. However, this finding may be focal and overlooked. Therefore, an appropriate immunohistochemical panel of stains is crucial to make the correct diagnosis. Due to variability of staining, more than one endothelial marker, including CD31, CD34, FLI1, ERG, or Factor VIII may be necessary to support the diagnosis. Of note, positive ERG immunostain is known to be found in up to 50% of prostate carcinomas.19 Evidence of Myc amplification, as seen in the current case report, may be supportive, as it is found in over half of the post-radiation angiosarcomas.20

The clinical features of our patient and the reported post-radiation epithelioid angiosarcoma are summarized in Table 1. Compared to the recently reported cases by Matoso et al,2 our patient had shorter interval after the previous radiation (six years), and much better outcome (20 months with no evidence of recurrence).

Table 1.

Clinical features of post-radiation epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder and prostate

| Authors | Age Sex | Location | Type of surgery | Additional treatment | History of other cancer | Time after radiation (years) | Followup (months) | Vascular markers | Epithelial markers | Additional studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Matoso et al | 71 Male | Bladder neck | TURB followed by cystoprostatectomy | N/A | Prostate | 10 | 7/DOD | CD31+, FVIII+ CD31+, | CK7+ | N/A |

| Matoso et al | 85 Male | Right lateral bladder wall | TURB | N/A | Prostate | 15 | 6/DOD | FVIII+, CD34+ CD31+, | CK7+ | N/A |

| Present case | 79 Male | Bladder neck and prostate | TURB followed by cystoprostatectomy | No | Prostate | 6 | 20/NED | CD34+, FLI1+, ERG+ | CK7+ | c-Myc amplification |

DOD: dead of disease; NA: Not available; NED: no evidence of disease; TURB: transurethral resection of the bladder.

In summary, primary angiosarcomas of the urinary bladder and prostate gland are exceedingly rare. They may pose considerable diagnostic difficulty in a partial sampling, particularly when there is a solid epithelioid pattern of growth. Awareness of the possibility of epithelioid angiosarcoma occurring in this location, particularly with a history of pelvic radiation, and use of appropriate immunohistochemical studies are crucial to establish a correct diagnosis.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no competing financial or personal interests.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Kulaga A, Yilmaz A, Wilkin RP, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder after irradiation for endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:245–6. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0336-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matoso A, Epstein JI. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder: A series of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:1377–82. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan MA, Moutos DM, Pippitt CH, Jr, et al. Vaginal and bladder angiosarcoma after therapeutic irradiation. South Med J. 1989;82:1434–6. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198911000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Navon JD, Rahimzadeh M, Wong AK, et al. Angiosarcoma of the bladder after therapeutic irradiation for prostate cancer. J Urol. 1997;157:1359–60. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)64980-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seethala RR, Gomez JA, Vakar-Lopez F. Primary angiosarcoma of the bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1543–7. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1543-PAOTB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tavora F, Montgomery E, Epstein JI. A series of vascular tumors and tumour-like lesions of the bladder. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1213–9. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31816293c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams S, Romaguera R, Kava B. Angiosarcoma of the bladder: Case report and review of the literature. ScientificWorldJournal. 2008;8:508–11. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2008.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campschroer T, van der Kwast TH, Jonges GN, et al. Angiosarcoma of the prostate: A more frequent finding in the future owing to radiotherapy? A literature review with treatment implications based on a case report. Scand J Urol. 2014;48:420–5. doi: 10.3109/21681805.2014.905632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chandan VS, Wolsh L. Postirradiation angiosarcoma of the prostate. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:876–8. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-876-PAOTP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo CC, Pisters LL, Troncoso P. Prostate cancer invading the rectum: A clinicopathological study of 18 cases. Pathology. 2009;41:539–43. doi: 10.1080/00313020903071611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphrey PA. Angiosarcoma of the prostate. J Urol. 2012;187:684–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphrey PA. American Society for Clinical Pathology. Prostate pathology Chicago: American Society for Clinical Pathology; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khaliq W, Meyer CF, Uzoaru I, et al. Prostate angiosarcoma: A case report and literature review. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2901–3. doi: 10.1007/s12032-012-0188-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F. WHO Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasov B, Munguia G, Mazal PR, et al. Epithelioid angiosarcoma of the bladder: Report of a new case with immunohistochemical profile and review of the literature. Pathology. 2011;43:290–3. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e328344e2fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warne RR, Ong JS, Snowball B, et al. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. Apr 1, Primary angiosarcoma of the bladder in a young female. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arlen M, Higinbotham NL, Huvos AG, et al. Radiation-induced sarcoma of bone. Cancer. 1971;28:1087–99. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1971)28:5<1087::AID-CNCR2820280502>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cahan WG, Woodard HQ, et al. Sarcoma arising in irradiated bone; report of 11 cases. Cancer. 1948;1:3–29. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(194805)1:1<3::AID-CNCR2820010103>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shen R, et al. Comprehensive assessment of TMPRSS2 and ETS family gene aberrations in clinically localized prostate cancer. Mod Pathol. 2007;20:538–44. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manner J, Radlwimmer B, Hohenberger P, et al. Myc high-level gene amplification is a distinctive feature of angiosarcomas after irradiation or chronic lymphedema. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:34–9. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]