Abstract

Introduction: Diagnosis and treatment of vaginal and cervical cytological cell changes are described in European and national guidelines. The aim of this data collection was to evaluate the remission rates of PAP III and PAP III D cytological findings in patients over a period of 3–4 months.

Method: The current state of affairs in managing suspicious and cytological findings (PAP III, and III D) in gynecological practice was assessed in the context of a data collection survey. An evaluation over a period of 24 months was conducted on preventative measures, the occurrence and changes to normal/suspect/pathological findings and therapy management (for suspicious or pathological findings).

Results: 307 female patients were included in the analysis. At the time of the survey 186 patients (60.6 %) had PAP III and 119 (38.8 %) had PAP III D findings. The spontaneous remission rate of untreated PAP III patients was 6 % and that of untreated PAP III D patients was 11 %. The remission rates of patients treated with a vaginal gel were 77 % for PAP III and 71 % for PAP III D.

Conclusion: A new treatment option was used in gynecological practice on patients with PAP III and PAP III D findings between confirmation and the next follow-up with excellent success.

Key words: PAP III, PAP III D, cervix, gynaecology

Zusammenfassung

Einleitung: Die Diagnose und Therapie zervikaler zytologischer Zellveränderungen sind in europäischen und nationalen gynäkologischen Leitlinien abgebildet. Ziel dieser Datenerhebung war die Erfassung der Remissionsraten von PAP III- und PAP III D-Befunden in Beobachtungszeiträumen von 3–4 Monaten.

Methode: Im Rahmen einer retrospektiven Datensammlung sollte der derzeitige Stand des Managements suspekter und pathologischer zytologischer Befunde (PAP III und III D) in der gynäkologischen Praxis erfasst werden. Über einen Zeitraum von 24 Monaten wurden durchgeführte Präventionsmaßnahmen, Auftreten und Veränderung normaler/suspekter/pathologischer Befunde sowie das Therapiemanagement (bei suspektem oder pathologischem Befund) evaluiert.

Ergebnisse: 307 Patientinnen wurden in die Analyse eingeschlossen. Zum Zeitpunkt der Erhebung hatten 186 Patientinnen (60,6 %) einen PAP III- und 119 Patientinnen (38,8 %) einen PAP III D-Befund. Die spontane Remissionsrate der unbehandelten PAP III-Patientinnen lag bei 6 %, jene der unbehandelten PAP III D-Patientinnen bei 11 %. Die Remissionsraten der mit einem Vaginalgel behandelten Patientinnen betrugen 77 % (PAP III) beziehungsweise 71 % (PAP III D).

Schlussfolgerung: In der gynäkologischen Praxis wird zu einem hohen Prozentsatz eine neue Therapieoption bei Patientinnen mit PAP III- und PAP III D-Befunden während der Zeitintervalle zur nächsten Kontrolluntersuchung mit ausgezeichneten Erfolgen eingesetzt.

Schlüsselwörter: PAP III, PAP III D, Zervix, Gynäkologie

Introduction

Cytological portio and cervical canal smear testing has been used routinely for many years and has now become common practice in the management of suspicious pathological smears. In Austria microscopic cell images are evaluated according to the currently valid Papanicolaou cytological classification scheme, based on the guideline of the Austrian Society of Cytology 2005 1. In Germany the Munich Nomenclature III is employed 2. In other European countries and in Anglo-American countries the Bethesda system is used 3.

The Papanicolaou classification differentiates severity categories. In this respect PAP I and PAP II correspond to benign and unobtrusive cell images. Alternatively, pathological findings of the cervix corresponding to stages PAP III, PAP III D, PAP IV and PAP V necessitate further gynecological investigation. PAP IV stages describe an already cancerous precursor or carcinoma in situ, while PAP V describes a carcinoma. PAP III and PAP III D are findings in gynecological practice with non-uniform clinical appearance, heterogeneous cellular findings and a heterogeneous forecast 1, 4. Correspondingly vague are also the statistics on national and global incidences of PAP III and PAP III D findings. In gynaecological practice, suspicious smears can result from extremely diverse influences and risk factors. These include other genital infections (e.g. Chlamydia, herpes), long-term continuous intake of oral contraceptives, smoking, high parity, immunosuppression, HIV infection and cervical inflammation 5, 6.

On obtaining positive PAP results of categories III, III D, III G, IV and V, recommendations of the guidelines of the Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (OEGGG) are to proceed, diagnose and treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and microcarcinoma of the cervix uteri. Depending on the PAP result, this includes various follow-up examinations, such as colposcopy, conisation, curettage, repeated PAP testing, HPV testing and histological investigation 4.

The waiting periods recommended in the guidelines concerning a PAP III and PAP III D diagnosis mean a treatment-free interval of several months (“watchful waiting”), which is an anxious period for those involved. Studies have shown that patients who are informed of a conspicuous PAP cytology test result generally react with anxiety, panic and stress 7, 8, 9. These reactions occur regardless of the severity of the findings 10 and can be traced back to a lack of information about causes, prevention, importance of the findings and treatment options 11.

Numerous publications show that for both PAP III and PAP III D findings spontaneous remissions and progressions occur, even without therapeutic intervention. Publications consistently reveal that not only remission, but also progression rates increase over long observation periods 12, 13, 14. Nasiell (1983) describes a regression of 62 % over a follow-up period of 39 months in the case of mild to moderate dysplasias. The rate of progression to higher-grade lesions is reported to be 16 % over a period of 48 months 13.

The objective of this data survey was to record the remission and progression rates associated with shorter follow-up periods (3–4 months), as well as management practices for suspicious and pathological cytological findings (PAP III and PAP III D) in gynaecological practice.

Methods

Data collection

Anonymous “test consultations” for all patients were established in the context of a data collection survey over a period of 24 months, which covered preventive measures, appearance and changes, such as normal/suspect/pathological findings and therapy management (of suspicious or pathological outcomes). This was made possible by data from files of patients who were treated at least once at the test centers during this period and who demonstrated PAP III/III D outcomes via questionnaires. To facilitate comparability of treatment management practices, two consecutive PAP smears were obtained (the first PAP III or III D) and instead of outcome data, only the time interval was documented. Center numbering did not permit comparison between individual physicians and their treatments. The applied questionnaire was prepared by a scientific consortium of the SFU (Sigmund Freud Private University, Vienna). Thereby the following were taken into account:

age groups,

PAP smear check-up intervals between two consecutive outcome reports,

HPV vaccination,

virus status, histological examination,

whether there were earlier suspicious diagnoses,

familial occurrence or risk factors,

diagnostics, and

therapy approaches.

The data collection was approved by the Ethics Commission of the City of Vienna.

Statistical methodology

The methods used in this study were selected to compare treatment with a special vaginal gel against other treatments. Statistical analysis took into account the influence of virus and infection status on the treatment by simple tests for random sampling. Improvements of PAP outcomes were determined using logistic regression models and methods of propensity score matching. Only two-sided tests were performed and a p-value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significantly. Statistical modeling and estimation of associated tests were carried out using the software R, version 15.2 15.

Results

Demographic data and history

In total 307 patients were included in the survey. Data, demographic information and two consecutive PAP test results obtained during the intervening interval were recorded.

The age distribution of subjects corresponded to the epidemiological distribution of affected patients. 170 patients (55.4 %) were in the age group 14 to 44 years, 132 patients (43.0 %) were in the age group 45 to 69 years and there were only five (1.6 %) patients in the age group 70+.

Only two patients (0.7 %) had participated in an HPV vaccination programme. 40 patients had a history of recurrent cervical inflammation. The anamnestic information about interventions and diseases principally included a cone biopsy (19 cases), curettage (two cases), polyp surgery (four cases), condylomata (three cases) and cesarean section (15 cases).

At the time of evaluation 186 patients (60.6 %) had PAP III and 119 patients (38.8 %) had PAP III D outcomes. Questionnaire information was not available for two patients (0.7 %). Total deviation (100.1 %) derived from mathematical roundings. HPV status was available for 117 patients (38.1 %) and this was positive for 29.6 %.

Non-surgical therapy approaches

A total of 216 out of 307 patients (70.4 %) received medication. 91 patients (29.6 %) received no medication and were merely observed. From the 216 patients, a large number (183) applied a vaginal gel (for composition see Table 5), 15 patients received a clotrimazole-containing cream as a topical antifungal treatment, 15 patients received an estriol-containing vaginal cream, eight patients were given an oral folic acid supplement and seven patients received oral antibiotic therapy with josamycin. Beta blockers, antirheumatoid/anti-inflammatories, immune modulators and vitamins and/or minerals were administered sporadically. These therapies had no statistical relevance due to their low frequency of use in the subject group and the heterogenous indications for which they were prescribed (data not shown).

Table 5 Composition of the intravaginal gel.

| Ingredient | Content in mg per application of 5 ml |

|---|---|

| * corresponds to 0.25 mg selenium per applicationExcipients: Water, hydroxyethyl cellulosePreservative: potassium sorbate, sodium benzoate | |

| Citric acid | 24.8 |

| Silicon dioxide, highly dispersed | 10.0 |

| Sodium selenite pentahydrate * | 0.83 |

Since the vaginal gel was used as a treatment during bridging of a therapy-free “watchful waiting” period, in accordance with OEGGG Guidelines, this group was evaluated separately in order to identify any potential benefit with regard to tolerability and influence on the remission tendency.

Two groups were determined as follows:

a vaginal gel group (183 patients; 59.6 %), and

a group without vaginal gel (124 patients; 40.4 %).

As this was an epidemiological study and not a randomized interventional study, the number of patients receiving vaginal gel therapy differed from those not receiving vaginal gel therapy.

The age distribution of the two patient groups is summarized in Table 1. The patient age distribution was balanced for both groups and the groups did not significantly differ by age.

Table 1 Age distribution of patient groups.

| Age distribution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 to 44 years | 45 to 69 years | 70+ years | |||||

| Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) Total | |

| * vaginal gel composition, see Table 5 Vaginal gel group: Total deviation (99.9 %) derived from mathematical roundings.n = number of patients | |||||||

| Therapy with vaginal gel* | 106 | 57.9 | 76 | 41.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 183 |

| Therapy without vaginal gel | 64 | 51.6 | 56 | 45.2 | 4 | 3.2 | 124 |

| Total | 170 | 55.4 | 132 | 43.0 | 5 | 1.6 | 307 |

Development of the PAP outcomes

The frequency of PAP III and PAP IIII D outcomes were initially described (section “descriptive outcomes”) descriptively and then compared statistically (results under “Impact of covariates on choice of medication”).

Descriptive outcomes

Patients who applied the vaginal gel corresponded to 44.8 % of the PAP III D outcomes (Table 2) and thereby they commenced treatment with a disadvantage.

Table 2 Initial PAP outcomes.

| Initial PAP outcome | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAP III | PAP III D | No data | ||||||

| Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) | Percent (%) | Number (n) | Percent (%) | |

| * vaginal gel – see Table 5 ** Total deviation (99.9 %) derived from mathematical roundings.n = number of patients | ||||||||

| Therapy with vaginal gel* | 100 | 54.6 | 82 | 44.8 | 1 | 0.5 | 183 | 100** |

| Therapy without vaginal gel | 86 | 69.4 | 37 | 29.8 | 1 | 0.8 | 124 | 100 |

| Total | 186 | 60.6 | 119 | 38.8 | 2 | 0.7 | 307 | 100 |

In both groups (PAP III and PAP III D) the second documented PAP cytology results improved compared with initial findings (Table 3).

Table 3 Results of second documented PAP outcomes.

| Second documented PAP outcome | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAP II | PAP III | PAP III D | PAP IV | Cone biopsy | ||||

| * vaginal gel – see Table 5 ** Total deviation (99.9 %) derived from mathematical roundings.n = number of patients | ||||||||

| Patient groups | Therapy with vaginal gel* | Number (n) | 136 | 20 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 183 |

| Percent (%) | 74.3 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 100** | ||

| Therapy without vaginal gel | Number (n) | 9 | 85 | 28 | 2 | 0 | 124 | |

| Percent (%) | 7.3 | 68.5 | 22.6 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 100 | ||

| Total | Number (n) | 145 | 105 | 119 | 4 | 1 | 307 | |

| Percent (%) | 47.2 | 34.2 | 16.9 | 1.3 | 0.3 | 100 | ||

A comparison between the vaginal gel treated group and the group that did not receive vaginal gel revealed significantly greater improvement rates in favor of the vaginal gel group. The spontaneous remission rate in the non-treated group was 6 % for PAP III outcomes and 11 % for PAP III D outcomes. In the vaginal gel group 77 % had improved PAP III outcomes and 71 % experienced an improved PAP III D diagnosis (Table 4).

Table 4 Cross table – development of PAP outcomes.

| Second documented PAP outcome | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAP II | PAP III | PAP III D | PAP IV | Cone biopsy | ||||

| * vaginal gel – see Table 5 ** Total deviation (99.9 %) derived from mathematical roundings.n = number of patients | ||||||||

| Therapy with vaginal gel* | PAP III | Number (n) | 77 | 16 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 100 |

| Percent (%) | 77.0 | 16.0 | 6.0 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 100 | ||

| PAP III D | Number (n) | 58 | 4 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 82 | |

| Percent (%) | 70.7 | 4.9 | 22.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 100 | ||

| No data | Number (n) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Percent (%) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | ||

| Total | Number (n) | 136 | 20 | 24 | 2 | 1 | 183 | |

| Percent (%) | 74.3 | 10.9 | 13.1 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 100** | ||

| Therapy without vaginal gel | PAP III | Number (n) | 5 | 74 | 7 | 0 | 86 | |

| Percent (%) | 5.8 | 86.0 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 100** | |||

| PAP III D | Number (n) | 4 | 10 | 21 | 2 | 37 | ||

| Percent (%) | 10.8 | 27.0 | 56.8 | 5.4 | 100 | |||

| No data | Number (n) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Percent (%) | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | |||

| Total | Number (n) | 9 | 85 | 28 | 2 | 124 | ||

| Percent (%) | 7.3 | 68.5 | 22.6 | 1.6 | 100 | |||

The group that did not receive the vaginal gel comprised 124 patients. This group also demonstrated improved outcomes. However, the degree of improvement was much less pronounced than that experienced by the vaginal gel user group (Table 4).

This descriptive finding was expanded upon with statistical analysis.

Impact of covariates on choice of medication

As this was an observational, non-interventional study and a collection of data, the data presented was not based on pure random sampling. Therefore comparison of simple arithmetic means or partial comparisons are not statistically valid. A priori it cannot be excluded that the choice of medication could depend (“yes” or “no”) on certain factors such as age, infection (“yes” or “no”), or virus status.

The influence of age, virus and infection status on the choice of medication must therefore be taken into account. Therefore, the influence of these covariates on the medication was eliminated through estimation of a logistic regression model. The propensity scores obtained in predicting health improvement (improvement of the PAP score) corresponded with the medication. These observed propensity score models in observational studies are state-of-the-art 16, 17, 18.

Subsequently, a statistical comparison was made between groups treated with the vaginal gel and the group that either did not receive the gel, received another treatment or no medication of any type, in terms of PAP score improvement.

As mentioned, treatment impact should be evaluated initially by specific covariates on the choice of medication. In this regard the influence of age, virus and infection status on the choice of medication was evaluated using a logistic regression model. The result of this modeling showed that both the infection status (p = 0.002) and the virus status (p = 0.019) have significant (positive or negative) impacts on the choice of medication, while age (divided into three age groups) had no significant influence on the choice of medication.

PAP improvement outcomes

Application of logistic regression in the previous section demonstrated that the choice of medication significantly depends on the patientʼs infection and virus status. Consequently these influences were eliminated by propensity score modeling 16, 17, 18.

Propensity scores from the modeling of the medication in the improvement of PAP outcomes were taken into account and included in the model. In this logistic regression model, PAP outcome improvement is medication-dependent and response propensity score-dependent. In such a case the propensity scores were divided into five equal-sized classes.

Findings were such that there was a highly statistically significant (p < 0.0001) influence associated with use of the vaginal gel.

The resulting p value of the non-parametric χ2 test statistic, to check whether the medication could be responsible for the improvements 18, revealed a probability value of p < 0.0001. The highly statistically significant impact of medication (vaginal gel versus other or no medication) on PAP outcome improvement is thereby confirmed. Alternatively, the influence of propensity scores for the prediction of PAP improvement was not significant. Despite the non-significant influence of propensity scores these should be included in the model to prevent skewed estimates.

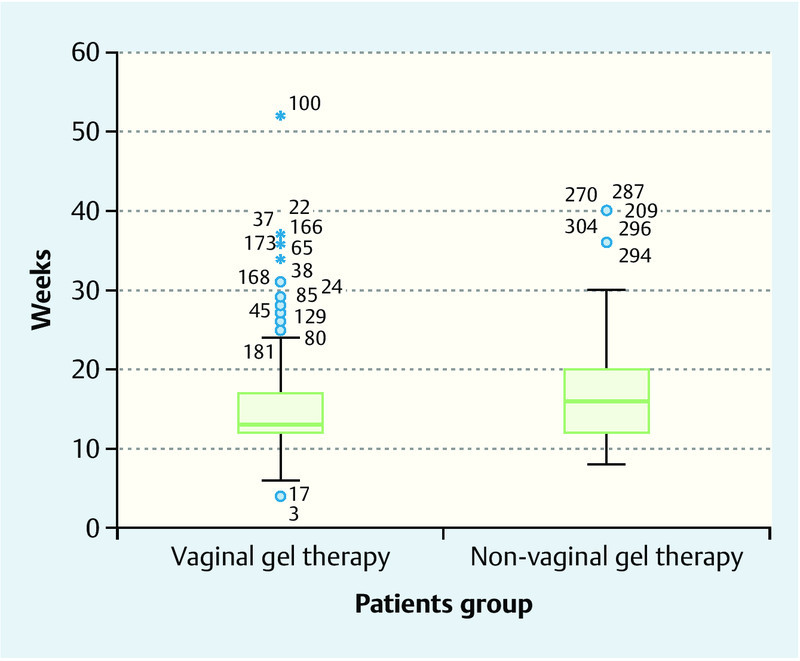

In patients treated with the vaginal gel, the interval up to the second PAP test was a median of 13.0 weeks, less than in the comparison group with a median of 16.0 weeks (Fig. 1). Thus, this group showed improvement over a shorter time than the other group.

Fig. 1.

Box plot of follow-up frequency between two PAP outcomes. The numbers outside the whiskers (3–304) refer to the patient record number.

Discussion

Abnormal PAP smear results are an enormous psychological burden for patients. In particular, the strategy of therapy-free “watchful waiting” is perceived as extremely tortuous by those concerned. New therapeutic approaches aim to promote the cervical remission processes. Achievements in this respect to-date have been very variable. Ferrante et al. (2002) and Conner et al. (2002) examined the effectiveness of a metronidazole-containing vaginal gel for atypical cytology outcomes and in terms of its influence on the remission rate of marginally conspicuous PAP outcomes. In both studies no positive cytological effect could be demonstrated 19, 20.

Marais et al. (2006) tested the efficacy of an alternative vaginal gel (Advantage S) in patients with HPV infection. This gel contained nonoxynol 9 as active ingredient. Results showed no preventive effect on HPV infections 21. Holmes et al. (1999) compared the anti-HPV properties of an intravaginal cream containing 5-fluorouracil against placebo. Follow-up after four to six months revealed a lower remission rate of the active treatment group compared with the control group 22.

Therapeutic trials have also examined the application of interferons. Evidence of efficacy is however inconsistent 23, 24. Topical interferon alpha-2b has been tested in an open study in HPV positive patients with PAP stages II w, III and III D (CIN 1). Two parallel studies were conducted methodically. In the interferon study the responder rate was 40 % (eight out of 20 patients showed improvements), whereas in the second study (untreated) regression was 33 % (seven out of 21 patients). These are the results of the intent-to-treat analysis. In the per protocol analysis 58.3 % (eight out of 12 patients) of patients in the interferon study showed a response, but this was only 36.8 % (seven of 19 patients) in the controlled study 25.

There has also been scientific interest in the application of imiquimod (5 % cream), a topical immune modulator. Its efficacy has been tested in recent years, primarily against vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia (VIN), penile intra-epithelial neoplasia (PIN) and anal intra-epithelial neoplasia (AIN) 26, 27, 28. A meta-analysis by Matho et al. (2010) describes ten trials involving 202 patients (two randomized, controlled trials with n = 83 and eight observational studies with n = 119) and nine case-control studies (n = 15 for PIN, n = 3 for AIN). The mean responder rates for the controlled and observational studies amounted to 51 % for VIN, 70 % for PIN and 48 % for AIN 29.

Recently a study has investigated the use of imiquimod for high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN 2 and 3, placebo-controlled trial, n = 59 patients). After 16 weeks of treatment with topical imiquimod, the histological findings improved in 75 % of patients. 46 % of patients experienced complete remission 30. Despite numerous therapeutic approaches, an effective therapeutic for the treatment of PAP III and PAP III D in the form of a vaginal gel or a vaginal cream is still not available.

This data analysis has shown that a high proportion of patients were treated with a novel vaginal gel (for composition see Table 5). The composition of the vaginal gel had been deduced from a formula successfully used in the treatment of topical inflammations such as fever blisters (cold sores) and stomatitis aphthosa. The gel is based on an aqueous hydroxyethyl cellulose matrix. The active substances contained in the gel are inert, highly-dispersed silicon dioxide as well as a combination of citric acid and sodium selenite. Toxicologically these substances are absolutely safe, both in qualitative and in quantitative terms, when used as intended. Irritation and hypersensitivity tests have not revealed any potential intolerabilities.

From investigations of the gelʼs mechanism of action, it can be concluded that its intravaginal-topical application results in “milieu cleansing” and favours the physiological remission tendency of suspicious PAP findings. As has been shown by fluorescence microscopy and SEC (size exclusion chromatography) tests, the primary mechanism of action of the vaginal gel is based on the adsorptive binding properties of the homogenously suspended, micronized silicon dioxide particles in the gel. In vitro tests demonstrate qualitatively and quantitatively that the silicon dioxide microparticles bind solid components and potentially pathogenic particles from the vaginal secretion. This prevents the propagation of these pathogens on the surfaces of the vaginal mucosa and the cervix. The secretion particles adhering to the silicon dioxide adsorbers are subsequently neutralised anti-oxidantly by the selenite-citric acid combination suspended in the vaginal gel.

This binding, neutralisation and elimination of potentially pro-oxidative vaginal secretion particles thus relieves the vaginal mucosa and the surface of the cervix, and thus promotes the physiological remission tendency of the irritated vagina and cervix.

The studies available so far have ruled out systemic effects of the vaginal gel, for instance caused by absorption of selenite. The principle of effect of the vaginal gel is thus based neither on pharmacological nor metabolic nor immunological effects. The vaginal gel therefore displays the mechanism of action of a medical device.

With once-daily application of this preparation, highly significant improvements in cytological PAP III and III D results could be observed. In a total population of 307 patients, more than 70 % of the patients in the vaginal gel group (n = 183) showed remission in terms of improved PAP result at the follow-up exam. Results indicate that the intravaginal-topical application of a vaginal gel stimulates the remission rate of suspicious PAP findings.

In accordance with the current gynaecological guidelines of the OEGGG on therapy management of PAP III and PAP III D findings (ASC-US, ASC-H, LSIL and HSIL according to the Bethesda classification), patients are often sent away from their doctor with therapy-free intervals until their next check-up appointment. On the one hand this is because remission is often spontaneous without the need for therapeutic intervention, as previously mentioned, and on the other hand to the lack of a causal therapy approach.

Results of this data survey, investigating intravaginal application of a gel suspension (Table 5), have identified a new therapy option for class III and III D cytological findings in gynaecological practice.

Conclusions for the Practitioner

For the first time gynaecologists now have the possibility to treat their PAP III and PAP III D patients during the therapy-free periods until the next check-up exam in conformity with the Guidelines. The stressful “watchful waiting” period can thus be bridged, and the remission tendency can be supported significantly with this treatment.

Acknowledgement

This project was conducted by the academic, independent study network ANISNet (Academic Non-Interventional Study Net) of the SFU (Sigmund Freud Private University), Vienna, Austria.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Leitlinien der ÖGZ zur Nomenklatur und zervixzytologischen Befundwiedergabe. Vorstandsbeschluss der ÖGZ vom 23.05.2005

- 2.Griesser H, Marquardt K, Jordan B. et al. Münchner Nomenklatur III. Frauenarzt. 2013;54:1042–1048. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apgar B S, Zoschnick L, Wright T C. The 2001 Bethesda System terminology. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1992–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breitenecker G, Girardi F, Joura E A. et al. Leitlinie für die Diagnose und Therapie von Cervicalen Intraepithelialen Neoplasien (CIN) und Mikrokarzinom der Cervix uteri. Speculum. 2005;23:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castellsagué X, Bosch F X, Muñoz N. Environmental co-factors in HPV carcinogenesis. Virus Res. 2002;89:191–199. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castle P E, Giuliano A R. Chapter 4: Genital tract infections, cervical inflammation, and antioxidant nutrients—assessing their roles as human papillomavirus cofactors. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2003;(31):29–34. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a003478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ideström M, Milsom I, Andersson-Ellström A. Womenʼs experience of coping with a positive Pap smear: A register-based study of women with two consecutive Pap smears reported as CIN 1. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82:756–761. doi: 10.1080/j.1600-0412.2003.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Mortensen G, Adeler A L. Qualitative study of womenʼs anxiety and information needs after a diagnosis of cervical dysplasia. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2010;18:473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10389-010-0330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monsonego J, Cortes J, da Silva D P. et al. Psychological impact, support and information needs for women with an abnormal Pap smear: comparative results of a questionnaire in three European countries. BMC Womens Health. 2011;11:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6874-11-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gray N M, Sharp L, Cotton S C. et al. Psychological effects of a low-grade abnormal cervical smear test result: anxiety and associated factors. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:1253–1262. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones M H, Singer A, Jenkins D. The mildly abnormal cervical smear: patient anxiety and choice of management. J R Soc Med. 1996;89:257–260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillemanns P, Thaler C, Kimmig R. Epidemiologie und Diagnostik der zervikalen intraepithelialen Neoplasie – Ist das derzeitige Konzept von Screening und Diagnostik noch aktuell? Gynäkol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 1997;37:179–190. doi: 10.1159/000272853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nasiell K, Nasiell M, Vaćlavinková V. Behavior of moderate cervical dysplasia during long-term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1983;61:609–614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iwasaka T, Hayashi Y, Yokoyama M. et al. Interferon gamma treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;37:96–102. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90316-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; ISBN 3-900051-07-0Online:http://www.r-project.orglast access: 03.03.2016

- 16.Rosenbaum P R, Rubin D B. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika. 1983;70:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearl J. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2009. Understanding propensity scores. Causality: models, reasoning, and inference. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chambers J M. Pacific Grove, California, USA: Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole; 1992. Chapter 4 of statistical Models in S. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrante J M, Mayhew D Y, Goldberg S. et al. Empiric treatment of minimally abnormal papanicolaou smears with 0.75 % metronidazole vaginal gel. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15:347–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Connor J P, Elam G, Goldberg J M. Empiric vaginal metronidazole in the management of the ASCUS Papanicolaou smear: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:183–187. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01725-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marais D, Carrara H, Kay P. et al. The impact of the use of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on the presence of cervical human papillomavirus in female sex workers. Virus Res. 2006;121:220–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes M M, Weaver S H 2nd, Vermillion S T. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 5-fluorouracil for the treatment of cervicovaginal human papillomavirus. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1999;7:186–189. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-0997(1999)7:4<186::AID-IDOG4>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sikorski M, Zrubek H. Recombinant human interferon gamma in the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Eur J Gynecol Oncol. 2003;24:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frost L, Skajaa K, Hvidman L E. et al. No effect of intralesional injection of interferon on moderate cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:626–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb02552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurzeja R, Böhmer G, Schneider A. Clinical outcome of topical interferon alpha-2b cream in phase II trial for LSIL/CIN 1 patients. J Cancer Ther. 2011;2:203–208. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fox P A, Nathan M, Francis N. et al. A double-blind, randomized controlled trial of the use of imiquimod cream for the treatment of anal canal high-grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV-positive MSM on HAART, with long-term follow-up data including the use of open-label imiquimod. AIDS. 2010;24:2331–2335. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833d466c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Seters M, van Beurden M, ten Kate F J. et al. Treatment of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1465–1473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Egmond S, Hoedemaker C, Sinclair R. Successful treatment of perianal Bowenʼs disease with imiquimod. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:318–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahto M, Nathan M, OʼMahony C. More than a decade on: review of the use of imiquimod in lower anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:8–16. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grimm C, Polterauer S, Natter C. et al. Treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia with topical imiquimod. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:152–159. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825bc6e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]