Abstract

For an IVF clinic that wishes to implement preimplantation genetic diagnosis for monogenic diseases (PGD) and for aneuploidy testing (PGD-A), a global improvement is required through all the steps of an IVF treatment and patient care. At present, CCS (Comprehensive Chromosome Screening)-based trophectoderm (TE) biopsy has been demonstrated as a safe, accurate and reproducible approach to conduct PGD-A and possibly also PGD from the same biopsy. Key challenges in PGD/PGD-A implementation cover genetic and reproductive counselling, selection of the most efficient approach for blastocyst biopsy as well as of the best performing molecular technique to conduct CCS and monogenic disease analysis. Three different approaches for TE biopsy can be compared. However, among them, the application of TE biopsy approaches, entailing the zona opening when the expanded blastocyst stage is reached, represent the only biopsy methods suited with a totally undisturbed embryo culture strategy (time lapse-based incubation in a single media). Moreover, contemporary CCS technologies show a different spectrum of capabilities and limits that potentially impact the clinical outcomes, the management and the applicability of the PGD-A itself. In general, CCS approaches that avoid the use of whole genome amplification (WGA) can provide higher reliability of results with lower costs and turnaround time of analysis. The future perspectives are focused on the scrupulous and rigorous clinical validations of novel CCS methods based on targeted approaches that avoid the use of WGA, such as targeted next-generation sequencing technology, to further improve the throughput of analysis and the overall cost-effectiveness of PGD/PGD-A.

Keywords: PGD, PGD-A, PGS, Trophectoderm biopsy, CCS, Embryo selection

Introduction

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) was introduced at the beginning of the 1990s as an alternative approach to prenatal diagnosis of genetically inherited diseases in couples at increased reproductive risk. Since then, the techniques to conduct genetic analysis have been constantly evolving and growing in their utilization. The clinical application of preimplantation genetic testing spread from sexing for family history of X-linked diseases [1], to a wide range of genetic indications. We can mention inherited genetic diseases, chromosomal abnormalities in the parental karyotype, e.g. reciprocal or Robertsonian translocations, and preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidies (PGD-A) to improve embryo evaluation, in those patients that experienced idiopathic recurrent miscarriage and/or repeated implantation failure, or are of advanced maternal age (AMA). Indeed, PGD is mainly adopted at present to conduct aneuploidy testing, PGD-A, and CCS-based analysis of trophectoderm (TE) biopsies at the blastocyst stage represents an extensively validated and clinically solid approach [2–5]. Briefly, the identification of the least invasive and most informative biopsy strategy was mainly focused on two critical issues: embryo viability and reproductive potential has not to be impacted, and the cellular material to analyse has to mirror the actual embryo genetic constitution with the highest possible accuracy. The only biopsy strategy that has been demonstrated to guarantee these two crucial aspects is TE biopsy at the blastocyst stage. At this stage of preimplantation development, the embryo is composed of 200–300 cells, which have differentiated into an inner cell mass (ICM) that potentially originates the foetus and the TE itself that instead gives origin to some embryonic annexes, such as the placenta. On average, 5–10 cells can be sampled at this stage from the TE without compromising embryo viability as demonstrated by Scott et al in their elegant non-selection paired randomized trial [6]. One of the foremost important advantages of TE biopsy is the possibility to obtain a higher starting amount of DNA with respect to single cell analysis, and this leads to a more accurate and reliable genetic test. Furthermore, the prevalence of diploid/aneuploid mosaicism at this stage of embryo development blastocysts is tolerable, accounting for about 5 % of the embryos at the blastocyst stage [7–10]. TE biopsy is also a cost-effective approach since only developmentally competent embryos are tested. Blastocyst culture itself does already select more competent embryos, providing higher implantation rate per transfer with respect to cleavage stage [11]. Finally, when TE biopsy is coupled with single embryo transfer (SET) policy, a reduction in multiple pregnancies with apparently no effect on the global efficacy of the treatment can be achieved [12, 13].

PGD/PGD-A progress requires the constant implementation of novel genetic techniques with higher throughput and resolution together with lower costs for the analysis, but also a more general possibility of implementation in all IVF settings, especially when the entailed procedures are applied on a large and systematic basis. The aim of this review is to evaluate the best laboratory approaches to improve the implementation of PGD/PGD-A in the daily clinical practice of an IVF centre.

Implementation of genetic and reproductive counselling in IVF cycles

The first step of implementation deals with the counselling of the couple that should be provided with thorough genetic and reproductive information. The key additional information to advise the couple are mainly as follows: for carriers of monogenic disorders or structural chromosomal abnormalities, the relevant patterns of inheritance and the impact of the disorder on the quality of life for an affected child as well as the possibility of using PGD as a reproductive option; for the general infertile population, the relevant prevalence of de novo aneuploidies that are expected in embryos in relation with female age, their contribution to implantation failures, miscarriages, stillbirths and new-borns with chromosomal syndromes. From a technical point of view, the need for embryo biopsy, the technical procedure, the diagnostic limits and biological impact on embryo development has to be discussed with the patients, as also the value of PGD/PGD-A in comparison to different forms of invasive and non-invasive prenatal diagnosis and testing. Moreover, couples should be informed about the possibilities that no embryo may be transferred since they can either do not develop to blastocysts or be all affected/aneuploid. In the post-test counselling period, it is important for patients to have a geneticist explaining in the details the clinical meaning and expected outcomes of the genetic results obtained. As for prenatal diagnosis, there are couples that might still consider the replacement of some affected embryos. It is also important to report the percentage of no results in relation to the biopsy stage and method of analysis used, and that a second round of warming and re-biopsy would be possibly needed. The patients should also be aware about the destiny of affected embryos that are not going to be transferred (e.g. discarding, cryopreservation, research, or donation), as established by the local legislation. Importantly, the diagnostic limitations of any technique should be acknowledged in terms of level of resolution as well as false positive/negative error rates [14] and this knowledge has to be used to further counsel pregnant couples after PGD testing in relation to invasive/non-invasive prenatal diagnosis (PND) procedures. This last point is of particular relevance since many couples might want to know what exactly is the reduction of the genetic risk they can benefit from in case of a pregnancy after PGD/PGD-A, and to what extent they can be confident in avoiding invasive PND. The couples undergoing an IVF cycle have usually had a frustrating reproductive history, and invasive PND is perceived as an additional source of stress and anxiety. Even though clear guidelines to this regard which are based on the use of contemporary biopsy and genetic technologies have not been established yet, it is important to provide patients with extended follow-up data of PGD pregnancies to make them able to take an informed and autonomous decision.

As discussed, the implementation of PGD/PGD-A in the clinical practice of an IVF centre requires a considerable investment of efforts and time for the reproductive and genetic counselling. Not just reproductive physicians should face with this detailed counselling, but a team of geneticists, which should be proportional to the expected volume of PGD/PGD-A cycles, is recommended to be involved in this phase.

Even though from a clinical perspective, the implementation is demanding, the improvement of PGD/PGD-A in IVF requires also major considerations and advancement in different other technical aspects that beset the application of embryos biopsy and genetic analysis. Specifically, efficient blastocyst stage culture, safe and effective trophectoderm (TE) biopsy and vitrification techniques, and molecular methods for accurate genetic testing are all critical steps that need to be implemented and optimized.

Implementation of trophectoderm biopsy approaches in an IVF laboratory

To perform the blastocyst biopsy approach, some basic but critical pre-requisites are required in the IVF laboratory before its implementation. First, the IVF laboratory has to be already experienced and set up for extended embryo culture. The right number of incubators has to be present to minimize the impact of suboptimal culture conditions on embryo development to the blastocyst stage and the use of low oxygen tension can be considered a mandatory step based on the most compelling scientific evidences to maximize blastocyst development [15]. Furthermore, blastocyst cryopreservation has to be an already established and effective tool before the implementation of the TE biopsy approach. In particular, vitrification protocols have to be already introduced and optimized in the IVF laboratory before attempting TE biopsy implementation. The preliminary evaluation of all these aspects is of critical importance for the overall success of any PGD/PGD-A approach.

Regarding the most efficient TE biopsy strategy to be implemented in IVF laboratory, there are two published protocols in literature to perform it. The first method [16] entails the laser-assisted zona pellucida drilling at the cleavage stage, followed by extended culture to the blastocyst stage. On day 5, both expanding and expanded blastocysts with herniating TE cells are biopsied, while cavitating morulas and early blastocysts are transferred again to a fresh blastocyst medium and biopsy is attempted 24 h later [17]. The zona opening at the cleavage stage was thought to promote an artificial TE cells herniation on day5 or 6, thus facilitating the TE separation during the biopsy (Fig. 1). Even though this is still nowadays the mostly used blastocyst biopsy approach, it shows some important limitations: the embryo must be taken out from the incubator in order to drill the zona pellucida at the cleavage stage, an avoidable source of extra stress during embryo culture, and the following preimplantation development can be impaired in terms of zona pellucida thinning, blastocyst expansion, and overall TE cells count. In addition, there is a risk for ICM herniation, a possibility that would make the biopsy a challenging rather than an easy procedure. The second method has been described in 2014 by our group [18]. This procedure does not entail any manipulation on day 3 of preimplantation development, so that the embryo is left undisturbed up to the blastocyst stage and does not show any artificially hatching cells, unless this is due to a physiological mechanism. Such a strategy allows the selection of TE cells to biopsy, since the zona opening and TE biopsy removal are sequentially performed when the ICM is clearly visible, not to involve it in the biopsy process (Fig. 1). Moreover, it provides a good synchronization of the blastocysts to be biopsied in day 5, day 6 or day 7 of preimplantation development and it is well suited with the use of a single media-based and/or a time-lapse microscopy (TLM)-based culture system (Fig. 2). Specifically, the oocyte after the ICSI can be put in culture in an ideal environment and never taken out from it up until its potential ultimate development as a fully expanded blastocyst. For centres that introduce this approach for the very first time, it can be initially adopted a day 5/6 hatching strategy. In particular, when the blastocyst reaches full expansion, it is taken out from the incubator, the zona pellucida is drilled by the laser and the embryo is put back into the incubator. This will allow in the following hours the herniation of the TE cells that are close to the hole. These cells would be then removed from the body of the blastocyst through the micromanipulator by alternating gentle suction via the mouth-controlled pipette and firing via the laser. This alternative TE biopsy approach is definitively easier to be performed for unexperienced practitioners (Fig. 1). Even though comparative studies of the three different TE biopsy approaches have not been reported yet, by avoiding the perturbation in embryo culture and the artificial and premature blastocyst hatching, we can putatively favour embryo progression to the blastocyst stage.

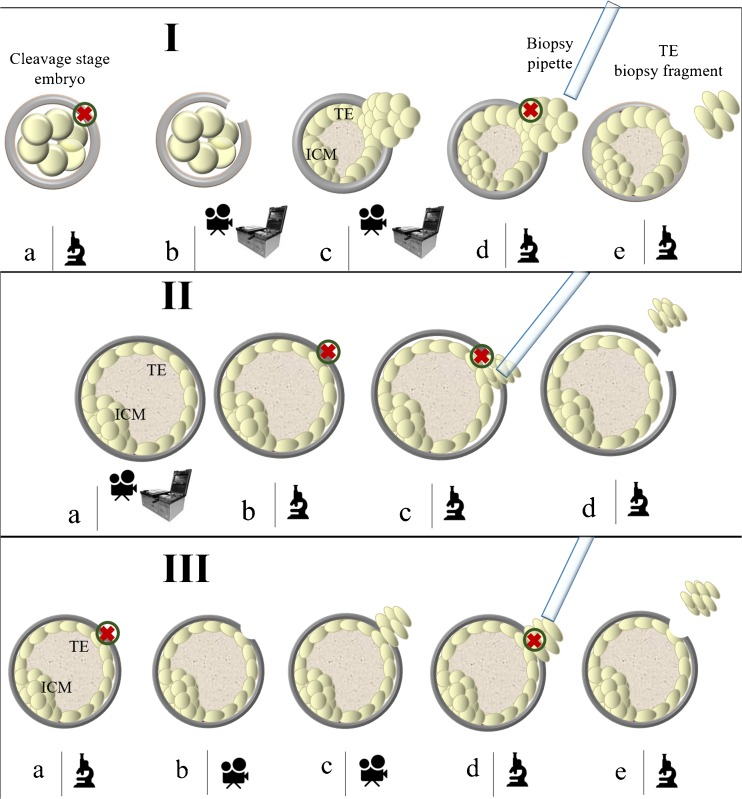

Fig. 1.

Blastocyst biopsy methods. I. Day3 hatching-based blastocyst biopsy method. (a) The embryo is taken out from the incubator on day3 of preimplantation development and the zona pellucida is drilled; (b) The embryo is culture up to the blastocyst stage either in time-lapse or in a standard incubator; (c) The trophectoderm cells (or in some cases also the Inner Cell Mass) will herniate from the opening in the zona pellucida; (d) The biopsy fragment is easily collected by firing with the laser at the junctions between the cells at the edges and the body of the blastocyst; (e) The biopsy fragment is released. II. Sequential zona opening and blastocyst biopsy method. (a) The embryo is cultured up to the fully-expanded blastocyst stage either in time-lapse or in a standard incubator; (b–c) The zona pellucida is drilled in a spot opposite to the Inner Cells Mass, the trophectoderm is gently detached from the it and few cells are sucked within the pipette to be then removed from the body of the blastocyst by alternating stretching and firing the laser; (d) The biopsy fragment is released. III. Day5/6 hatching-based blastocyst biopsy method. (a) The blastocyst is taken out from the incubator in order to drill the zona pellucida on day5 or day6 of preimplantation development. Importantly, the inner cell mass is kept opposite to the spot where zona is opened; (b–c) The blastocyst is put back into the incubator until few trophectoderm cells will herniate; (d) The biopsy fragment is easily collected by firing with the laser at the junctions between the cells at the edges and the body of the blastocyst; (e) The biopsy fragment is released. The microscope icon identifies the steps conducted under the laser-equipped micromanipulator; the camera icon identifies the steps preferably conducted in a time-lapse system; the steps identified by the incubator and camera icons can be either conducted in a time-lapse system or in a conventional incubator. ICM, Inner Cell Mass; TE, trophectoderm; green circle with inner red cross, laser’s target

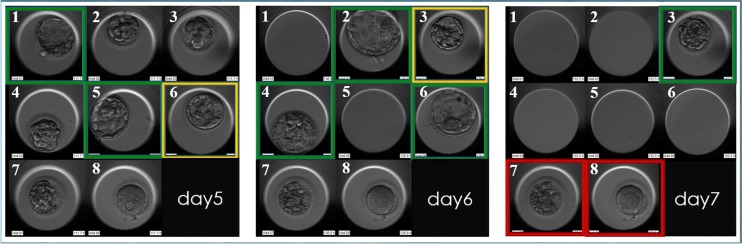

Fig. 2.

The blastocyst biopsy approaches that omit the day 3 hatching step guarantee a better synchronization between physiological embryo development and daily laboratory management. In this example in day 5 of preimplantation development, embryo n1 and n5 reach full expansion and undergo trophectoderm (TE) biopsy and cryopreservation soon after. Embryo n6 is kept in culture in a time-lapse instrument up to day6. In day 6, embryo n2, n4 and indeed n6 undergo TE biopsy and cryopreservation. Embryo n3 is given a last chance to develop as a fully expanded blastocyst, and kept in culture up to day 7, when it is finally biopsied and cryopreserved. Green boxes identify blastocyst selected for biopsy; orange boxes identify blastocysts that are kept in culture in time-lapse on each specific day of preimplantation development; red boxes identify embryos that did not develop as blastocysts

Zona pellucida drilling is a required step for all the TE biopsy methods. It can be achieved through laser pulses [19], Tyrode acid [20] or mechanically [21]. The clinical results after the use of these three methods are comparable, as it has been reported in several RCTs on sibling embryos [22–24]. However, laser-based zona drilling is the most standardized and reproducible approach. Indeed, it is less operator-dependent [24] and less time-consuming and a shorter learning curve is required to acquire this skill. Nevertheless, the considerable raise in the temperature of the culture media surrounding the embryo during the firing procedure [25] was perceived as a concern. However, to this regard, Taylor and colleagues [26] clearly showed that it does not compromise neither technical nor clinical outcomes [26], finally providing evidences for its safe use.

The main persisting constraint of blastocyst stage biopsy strategy is that only experienced IVF laboratories can safely perform this approach, a limiting factor for its widespread application at this time. Specifically, this is due to the need for extended embryo culture, an efficient cryopreservation program and skilled embryologists to conduct TE biopsies, which are all critical factors that can compromise the ultimate efficacy of the IVF-PGD treatment if not performed properly [27, 28].

Selection of the blastocysts to undergo trophectoderm biopsy

A multicentre study we published in 2014 provided data to accurately assess the relationship between conventional parameters used for blastocyst evaluation and CCS analysis, as well as their role as additional tool to predict the implantation potential of euploid embryos [18]. In this study, blastocyst evaluation was based on embryological variables as embryo morphological quality, day of biopsy, and ICM and TE scores. The logistic regression analysis showed that blastocyst morphology is mildly predictive of the CCS data, as embryos with the highest morphological scores showed a higher euploidy rate compared with the worse quality embryos. Still though, almost half of the excellent quality blastocysts were aneuploid and 1/4 of the poor quality ones were euploid. Faster and slower growing embryos showed instead a similar euploidy rate and, finally, ICM and TE scores were independent variable from euploidy testing data. In particular, in this study, day 7 blastocysts have been included and, even if they represent approximately 5–7 % of the embryos reaching blastocyst, they showed similar euploidy rate compared to faster growing ones. About implantation, the logistic regression analysis adjusted for confounding factors showed that morphology and developmental rate were not predictive of the developmental potential of euploid embryos. Therefore, poor and average quality euploid embryos yielded the same ongoing implantation rate compared to excellent and good morphological quality ones. The implantation potential of euploid embryos that reach the blastocyst stage at different day post fertilization was also similar. ICM and TE grade were also not related to the implantation outcomes of euploid embryos. In conclusion, euploidy and reproductive competence cannot be predicted by conventional parameters of blastocysts evaluation and any embryo reaching to the fully expanded blastocyst stage should be given a chance to be biopsied and possibly transferred, in order not to impact the IVF treatment efficacy. In particular, bad quality and slowest growing day 7 blastocyst has to be similarly considered for biopsy because if euploid they also provide a significant reproductive potential. This study though is limited by its retrospective fashion, and studies that conjugate the predictive potential upon implantation of both euploidy plus morphological evaluation in a prospective non-selection fashion are still eagerly needed.

Finally, one of the most attractive advances of the last decade in human embryology has been the introduction of sophisticated time-lapse equipment and new culture conditions that allow undisturbed embryo development with a continuous control in a single media. Morphokinetic analysis of embryo development in vitro includes various events (e.g. syngamy, cleavages, compaction and blastulation), and in a study in published in 2014, we evaluated the possibility to use these parameters and previously published methods to detect aneuploidies and to foresee embryo implantation potential [29]. Differently from previous reports [30, 31], no correlation was found between aneuploidy rate and the 16 morphokinetic parameters analysed from ICSI up to completed blastulation. Indeed, the predictive power of time-lapse criteria upon embryo reproductive competence has not been defined yet and they cannot even be considered reliable to define whether a blastocyst should be biopsied or not [32, 33]. In conclusion, our recommendation is thus to include in the biopsy programme all embryos reaching the expanded stage, regardless their morphology.

Selecting the genetic technologies for genetic testing

A substantial improvement of molecular biology and cytogenetic techniques adopted for PGD/PGD-A was essential during the last decades. Briefly, to detect single gene disorder, the use of short tandem repeats (STRs) analysis has been complemented by novel technologies based on the use single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), such as SNP-array to conduct linkage based analysis or qPCR approach to detect the mutation and flanking informative SNPs by TaqMan genotyping [34–36]. To analyse the unbalanced products of translocation, inversion, or other abnormalities of the parental karyotype and de novo aneuploidies, we moved from traditional cytogenetics techniques as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), which is able to analyse just few chromosomes with a considerable error rate [37] to 24-chromosome testing technologies. Among contemporary CCS technologies, there are array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) and SNP microarray. It is important to highlight that the introduction of microarray has been possible thanks to the development of whole genome amplification (WGA) strategies. This approach allows the random amplification of the genome starting from multiple loci in order to obtain sufficient DNA template to conduct microarrays-based analysis. The last and one of the most validated method for CCS of human blastocysts is real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), a method based on a preliminary targeted DNA enrichment based on a conventional PCR amplification followed by the quantification of the amplicons on a real-time reaction [38–40]. Its reliability has been demonstrated by measuring the technical accuracy in two papers. In the first paper 2, kinds of analysis were performed: (i) fibroblast cell lines with previously characterized karyotypes showed a 100 % of diagnostic consistency when tested by qPCR-based CCS of 5-cell samples [41]; (ii) blastocysts diagnosed as aneuploid by SNP-array were re-analysed on a second biopsy by qPCR and showed 99.94 % of consistency on a per chromosome basis and 98.6 % on a per embryo basis. The second paper involved instead the re-evaluation by qPCR of human blastocysts that were given an aneuploid diagnosis by aCGH [39]. To reduce the impact of mosaicism and biologic variation on the evaluation of qPCR technical accuracy, whenever a discordant diagnosis was found between qPCR and aCGH, a third fragment was analysed by SNP-array. This study design guaranteed the definition of a 99.9 % level of consistency between all the CCS methods according to a per chromosome-based analysis. However, it was reported a 7 % false positive error rate per chromosome for aCGH that is putatively ascribable to an amplification bias derived from WGA [39] (all the present and future CCS methods are compared in Table 1). Accordingly, all methods using WGA as enrichment step are at potential risk of such technical artefacts.

Table 1.

Comparison between comprehensive chromosome screening technologies for PGD-A. ++, very high; +, high; -, low; --, very low

| Validation on cell samples of known karyotype | Validation on blastocyst re-biopsies | Clinical validation in RCTs | Clinically recognizable error rate per live birth | Simultaneous single gene diagnosis | Lab workload | Cost of the analysis | Turnaround time | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGA-based approaches | aCGH | -- | + | 1 | 0.7 % | No | + | + | + |

| SNP-array | + | + | 1 | Not reported | Yes | ++ | ++ | ++ | |

| WGA-NGS | -- | - | 0 | Not reported | Possible | ++ | - | ++ | |

| Targeted-based approaches | qPCR | ++ | ++ | 2 | 0.2 % | Yes | -- | - | -- |

| t-NGS | + | + | 0 | Not reported | Possible | ++ | -- | ++ |

In a recent longitudinal cohort study, we evaluated the consistency and reproducibility of laboratory and clinical outcomes, across multiple TE biopsy practitioners from different IVF centres [42]. The quality of the biopsied samples was assessed for each biopsy operator, by evaluating the diagnostic rate, sample-specific concurrence of qPCR data and the estimated number of cells retrieved within the biopsy. The results obtained from seven operators in three different IVF centres showed that blastocyst biopsies display a really high conclusive diagnosis rate (96 %), and a minimal amplification failure events rate (1.2 %) or low quality results. The estimated cellularity of the biopsy, significantly associated with better quality of the CCS diagnosis and conclusive diagnosis rate, showed no differences between different biopsy practitioners. Finally, no impact of the operator on the observed ongoing implantation rates, biochemical pregnancy loss and miscarriage after frozen euploid SET cycles was reported. However, a limiting factor of these data is that they were produced in a restricted set of laboratories, where all the embryologists received identical training and used identical equipment, and only by qPCR analysis. It still needs to be determined what is the effectiveness of these approaches when implemented in less experienced IVF laboratories.

Importantly, qPCR has been also extensively validated to detect single gene mutations or small duplications and deletions. This is an additional possibility as in most cases, the women from couples that require PGD are of advanced reproductive age, thus presenting also an increased risk for embryonic aneuploidies. Remarkably, simultaneously PGD-A and PGD can be done on the same biopsy, within 4–6 h and in a cost-effective way [36]. Moreover, such a low turnaround time makes qPCR also compatible with fresh embryo transfer. Finally, two out of the three randomized controlled trials that compared PGD-A versus standard care in IVF performed so far have been carried out using qPCR [13, 40]. The limitation of the qPCR approach for CCS is related to the lower chromosomal resolution compared with contemporary microarray and NGS technologies, since partial aneuploidies cannot be detected (Table 1).

Future perspectives in comprehensive chromosome screening

As the advancement of novel techniques keeps moving forward, it is already possible to conduct a genome-wide analysis of the embryo in the preimplantation window by next generation sequencing (NGS) approaches. However, NGS approaches that entail WGA hold the potential to share similar drawbacks described previously for array-based methods that can be responsible for the production of data of extremely difficult interpretation and clinical management. To this regard, efforts have been invested to develop a NGS technology which instead provides a unique opportunity to evaluate multiple customizable genomic loci, so that in a multiplex PCR, they can be amplified by both the target sequences for the detection of single gene mutation and the chromosome-specific sequences in order to perform CCS [43, 44]. This second NGS approach does not entail a whole genome analysis, but it is a targeted-NGS (t-NGS) approach. This t-NGS approach, which is based on the same procedural concept at the basis of qPCR, has a lower theoretical resolution than WGA-NGS, but it minimizes the bias of amplification that could impact the final results. However, further studies are required to identify the depth and coverage needed to maintain a sufficient accuracy for both the methods. Therefore, before NGS can be adopted clinically, extensive preclinical validation and randomized controlled trials are definitively required for both its methodological approaches.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the implementation of PGD/PGD-A in IVF clinical practice is a multidisciplinary and demanding task, which requires improvements in the counselling of the couple, in embryological as well as in genetic techniques. So it is of utmost importance that all standard IVF procedures are very well consolidated (blastocysts culture, cryopreservation, blastocyst biopsy), and it is necessary to establish a connection with a genetic laboratory very well experienced with PGD/PGD-A. A mutual feedback between the gynaecologic, the embryologic and the genetic teams is pivotal for the success of a PGD/PGD-A programme and for its future improvement. Besides the challenges for its implementation, clearly, as PGD-A is showing increasing evidences to drastically improve IVF clinical outcomes providing a safer and more effective treatment, it is foreseeable that more and more IVF clinics worldwide will invest and put efforts into the implementation of this technology in the near future.

Footnotes

Future efforts will focus on clinical validation of novel CCS methods based on approaches replacing the use of WGA with targeted next-generation sequencing technology, to improve the throughput of analysis and the overall cost effectiveness of PGD/PGD-A.

References

- 1.Handyside AH, Kontogianni EH, Hardy K, Winston RM. Pregnancies from biopsied human preimplantation embryos sexed by Y-specific DNA amplification. Nature. 1990;344(6268):768–770. doi: 10.1038/344768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee E, Illingworth P, Wilton L, Chambers GM. The clinical effectiveness of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for aneuploidy in all 24 chromosomes (PGD-A): systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(2):473–483. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahdouh EM, Balayla J, García-Velasco JA. Comprehensive chromosome screening improves embryo selection: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(6):1503–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dahdouh EM, Balayla J, Audibert F, Genetics Committee. Wilson RD, Audibert F, Brock JA, Campagnolo C, Carroll J, Chong K, Gagnon A, Johnson JA, MacDonald W, Okun N, Pastuck M, Vallée-Pouliot K. Technical update: preimplantation genetic diagnosis and screening. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2015;37(5):451–63. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen M, Wei S, Hu J, Quan S. Can comprehensive chromosome screening technology improve IVF/ICSI outcomes? A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(10) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Scott RT, Jr, Upham KM, Forman EJ, Zhao T, Treff NR. Cleavage-stage biopsy significantly impairs human embryonic implantation potential while blastocyst biopsy does not: a randomized and paired clinical trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:624–630. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fragouli E, Lenzi M, Ross R, Katz-Jaffe M, Schoolcraft WB, Wells D. Comprehensive molecular cytogenetic analysis of the human blastocyst stage. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2596–2608. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson DS, Cinnioglu C, Ross R, Filby A, Gemelos G, Hill M, Ryan A, Smotrich D, Rabinowitz M, Murray MJ. Comprehensive analysis of karyotypic mosaicism between trophectoderm and inner cell mass. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;12:944–949. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Northrop LE, Treff NR, Levy B, Scott RT., Jr SNP microarray-based 24 chromosome aneuploidy screening demonstrates that cleavage-stage FISH poorly predicts aneuploidy in embryos that develop to morphologically normal blastocysts. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;8:590–600. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Capalbo A, Bono S, Spizzichino L, Biricik A, Baldi M, Colamaria S, et al. Sequential comprehensive chromosome analysis on polar bodies, blastomeres and trophoblast: insights into female meiotic errors and chromosomal segregation in the preimplantation window of embryo development. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:509–518. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glujovsky D, Blake D, Farquhar C, Bardach A. Cleavage stage versus blastocyst stage embryo transfer in assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD002118. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002118.pub4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ubaldi FM, Capalbo A, Colamaria S, Ferrero S, Maggiulli R, Vajta G, Sapienza F, Cimadomo D, Giuliani M, Gravotta E, Vaiarelli A, Rienzi L. Reduction of multiple pregnancies in the advanced maternal age population after implementation of an elective single embryo transfer policy coupled with enhanced embryo selection: pre- and post-intervention study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(9):2097–2106. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman EJ, Hong KH, Ferry KM, Tao X, Taylor D, Levy B, Treff NR, Scott RT., Jr In vitro fertilization with single euploid blastocyst transfer: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(1):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Practice Committee of Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine Preimplantion genetic testing: a Practice Committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5 Suppl):S136–S143. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wale PL, Gardner DK. The effects of chemical and physical factors on mammalian embryo culture and their importance for the practice of assisted human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update. 2016;22(1):2–22. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmv034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McArthur SJ, Leigh D, Marshall JT, de Boer KA, Jansen RP. Pregnancies and live births after trophectoderm biopsy and preimplantation genetic testing of human blastocysts. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(6):1628–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schoolcraft WB, Fragouli E, Stevens J, Munne S, Katz-Jaffe MG, Wells D. Clinical application of comprehensive chromosomal screening at the blastocyst stage. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(5):1700–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capalbo A, Rienzi L, Cimadomo D, Maggiulli R, Elliott T, Wright G, Nagy ZP, Ubaldi FM. Correlation between standard blastocyst morphology, euploidy and implantation: an observational study in two centers involving 956 screened blastocysts. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(6):1173–1181. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feichtinger W, Strohmer H, Fuhrberg P, Radivojevic K, et al. Photoablation of oocyte zona pellucida by erbium-YAG laser for in-vitro fertilisation in severe male infertility. Lancet. 1992;339(8796):811. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91938-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cohen J, Alikani M, Garrisi JG, Willadsen S. Micromanipulation of human gametes and embryos: ooplasmic donation at fertilization. Hum Reprod Update. 1998;4(2):195–196. doi: 10.1093/humupd/4.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J, Malter H, Elsner C, Kort H, et al. Immunosuppression supports implantation of zona pellucida dissected human embryos. Fertil Steril. 1990;53(4):662–665. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(16)53460-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eldar-Geva T, Srebnik N, Altarescu G, Varshaver I, et al. Neonatal outcome after preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Fertil Steril. 2014;102(4):1016–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Vos A, Van Steirteghem A. Aspects of biopsy procedures prior to preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2001;21(9):767–780. doi: 10.1002/pd.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geber S, Bossi R, Lisboa CB, Valle M, et al. Laser confers less embryo exposure than acid tyrode for embryo biopsy in preimplantation genetic diagnosis cycles: a randomized study. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2011;9:58. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rink K, Delacrétaz G, Salathé RP, Senn A, et al. Non-contact microdrilling of mouse zona pellucida with an objective-delivered 1.48-microns diode laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1996;18(1):52–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1996)18:1<52::AID-LSM7>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor TH, Gilchrist JW, Hallowell SV, Hanshew KK, et al. The effects of different laser pulse lengths on the embryo biopsy procedure and embryo development to the blastocyst stage. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2010;27(11):663–667. doi: 10.1007/s10815-010-9461-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capalbo A, Rienzi L, Ubaldi FM. New approaches for multifactor preimplantation genetic diagnosis of monogenic diseases and aneuploidies from a single biopsy. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(2):297–298. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cimadomo D, Capalbo A, Ubaldi FM, Scarica C, Palagiano A, Canipari R, Rienzi L. The impact of biopsy on human embryo developmental potential during preimplantation genetic diagnosis. BioMed Research International 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Rienzi L, Capalbo A, Stoppa M, Romano S, Maggiulli R, Albricci L, Scarica C, Farcomeni A, Vajta G, Ubaldi FM. No evidence of association between blastocyst aneuploidy and morphokinetic assessment in a selected population of poor-prognosis patients: a longitudinal cohort study. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2014.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Basile N, Nogales Mdel C, Bronet F, Florensa M, Riqueiros M, Rodrigo L, García-Velasco J, Meseguer M. Increasing the probability of selecting chromosomally normal embryos by time-lapse morphokinetics analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(3):699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell A, Fishel S, Bowman N, Duffy S, Sedler M, Thornton S. Retrospective analysis of outcomes after IVF using an aneuploidy risk model derived from time-lapse imaging without PGS. Reprod Biomed Online. 2013;27(2):140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2013.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaser DJ, Racowsky C. Clinical outcomes following selection of human preimplantation embryos with time-lapse monitoring: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2014;20(5):617–631. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkegaard K, Ahlström A, Ingerslev HJ, Hardarson T. Choosing the best embryo by time lapse versus standard morphology. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(2):323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Handyside AH, Harton GL, Mariani B, Thornhill AR, Affara N, Shaw MA. Karyomapping: a universal method for genome wide analysis of genetic disease based on mapping crossovers between parental haplotypes. J Med Genet. 2010;47:651–658. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rechitsky S, Pakhalchuk T, San Ramos G, Goodman A, Zlatopolsky Z, Kuliev A. First systematic experience of preimplantation genetic diagnosis for single-gene disorders, and/or preimplantation human leukocyte antigen typing, combined with 24-chromosome aneuploidy testing. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(2):503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmerman RS, Jalas C, Tao X, Fedick AM, Kim JG, Pepe RJ, Northrop LE, Scott RT, Jr, Treff NR. Development and validation of concurrent preimplantation genetic diagnosis for single gene disorders and comprehensive chromosomal aneuploidy screening without whole genome amplification. Fertil Steril. 2016;105(2):286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treff NR, Levy B, Su J, Northrop LE, Tao X, Scott RT., Jr SNP microarray-based 24 chromosome aneuploidy screening is significantly more consistent than FISH. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010;16:583–589. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaq039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Treff NR, Scott RT., Jr Four-hour quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction-based comprehensive chromosome screening and accumulating evidence of accuracy, safety, predictive value, and clinical efficacy. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1049–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Capalbo A, Treff NR, Cimadomo D, Tao X, Upham K, Ubaldi FM, Rienzi L, Scott RT., Jr Comparison of array comparative genomic hybridization and quantitative real-time PCR-based aneuploidy screening of blastocyst biopsies. Eur J Hum Genet. 2015;23(7):901–906. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2014.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott RT, Jr, Upham KM, Forman EJ, Hong KH, Scott KL, Taylor D, Tao X, Treff NR. Blastocyst biopsy with comprehensive chromosome screening and fresh embryo transfer significantly increases in vitro fertilization implantation and delivery rates: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(3):697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Treff NR, Tao X, Ferry KM, Su J, Taylor D, Scott RT., Jr Development and validation of an accurate quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction-based assay for human blastocyst comprehensive chromosomal aneuploidy screening. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):819–824. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Capalbo A, Ubaldi FM, Cimadomo D, Maggiulli R, Patassini C, Dusi L, Sanges F, Buffo L, Venturella R, Rienzi L. Consistent and reproducible outcomes of blastocyst biopsy and aneuploidy screening across different biopsy practitioners: a multicentre study involving 2586 embryo biopsies. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(1):199–208. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Treff NR, Fedick A, Tao X, Devkota B, Taylor D, Scott RT., Jr Evaluation of targeted next-generation sequencing-based preimplantation genetic diagnosis of monogenic disease. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1377–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner MD, Franasiak JM, Hong KH, Juneau CR, Tao X, Landis J, Upham KM, Treff NR, Scott RT. A prospective, blinded, non-selection study to determine the predictive value of ploidy results using a novel method of targeted amplification based next generation sequencing (NGS) for comprehensive chromosome screening (CCS). ASRM abstract book 2015.