Abstract

The complement system plays a central role in immunity and inflammation, although certain pathogens can exploit complement to undermine protective immunity. In this context, the periodontal keystone pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis (Pg) was previously shown by our group to evade killing by neutrophils or macrophages through exploitation of complement C5a receptor 1 (C5aR1) and complement receptor-3 (CR3). Here, we examined whether Pg uses complement receptors to also subvert killing by dendritic cells. In line with earlier independent studies, intracellular viable Pg bacteria could be recovered from mouse bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) or human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDC) exposed to the pathogen. However, in the presence of C5a, the intracellular survival of Pg was significantly decreased in a C5aR1-dependent way. Further work using wild-type and receptor-knockout BMDC showed that, in the presence of C3a, the C3a receptor (C3aR) similarly enhanced the intracellular killing of Pg. In contrast, C5aR2, an alternative receptor for C5a (G protein-coupled receptor 77), was associated with increased intracellular Pg viable counts, consistent with the notion that C5aR2 functions as a negative regulator of C5aR1 activity. Moreover, Pg failed to utilize CR3 as a phagocytic receptor in BMDCs, in contrast to our earlier findings in macrophages where CR3-mediated uptake promotes Pg survival. Collectively, these data show that complement receptors mediate cell-type-specific effects on how innate leukocytes handle Pg, which appears to exploit complement to preferentially evade those cells (neutrophils and macrophages) that are most often encountered in its predominant niche, the periodontal pocket.

Keywords: Immune evasion, intracellular killing, P. gingivalis, dendritic cells, complement, C3aR, C5aR1, C5aR2, CR3

INTRODUCTION

Porphyromonas gingivalis is a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium that is strongly associated with human periodontitis (Hajishengallis & Lamont, 2012; Hong et al., 2015). Extensive research over the past three decades have identified a number of documented or putative virulence factors of P. gingivalis that are thought to contribute to its persistence in the periodontal pocket (Bostanci & Belibasakis, 2012; Darveau et al., 2012; Hajishengallis & Lamont, 2014; Yilmaz, 2008). More recent work has started to elucidate how this bacterium integrates its virulence traits to enhance the pathogenic potential, or nososymbiocity, of polymicrobial communities (Hajishengallis & Lamont, 2016; Lamont & Hajishengallis, 2015). In this regard, studies in mice have shown that the capacity of P. gingivalis to induce periodontitis requires the indigenous microbiota, which is rendered dysbiotic in the presence of P. gingivalis (Hajishengallis et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2014). The aptitude of P. gingivalis to orchestrate inflammatory disease through community-wide effects, while being a low-abundance constituent of periodontitis-associated communities in humans and animal models (Abusleme et al., 2013; Hajishengallis et al., 2011), has prompted its designation as a keystone pathogen (Darveau, 2009; Darveau et al., 2012; Hajishengallis et al., 2012).

Although centrally involved in immunity and inflammation, the complement system can be subverted by various pathogens to promote their adaptive fitness in the mammalian host (Hajishengallis & Lambris, 2011; Lambris et al., 2008). The triggering of the complement cascade proceeds via distinct mechanisms (classical, lectin, or alternative), all of which converge at the third complement component (C3) (Ricklin et al., 2010). C3 activation by pathway-specific C3 convertases leads to the generation of effector molecules involved in (a) the recruitment and activation of inflammatory cells (e.g., the C3a and C5a anaphylatoxins that activate specific G-protein–coupled receptors, C3a receptor [C3aR] and C5a receptor 1 [C5aR1; CD88], respectively); (b) microbial opsonization and phagocytosis (e.g., through the C3b opsonin); and (c) direct lysis of targeted susceptible bacteria (by means of the C5b-9 membrane attack complex) (Ricklin et al., 2010). An alternative but quite enigmatic receptor for C5a is the C5aR2 (also known as C5a-like receptor 2 or GPR77), which has been assigned both regulatory and proinflammatory roles, depending on specific context (Gerard et al., 2005; Li et al., 2013; Ward, 2009).

Mechanistic studies have shown that the subversion of complement is fundamental to the ability of P. gingivalis to modulate innate immunity and instigate quantitative and qualitative alterations in the indigenous microbiota, which can thereby cause inflammatory bone loss in the oral cavity (Hajishengallis et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2014). In this context, we have previously shown that P. gingivalis can protect itself and bystander bacteria by interfering with leukocyte killing mechanisms while promoting inflammation, thereby contributing to dysbiosis (Liang et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2010). In neutrophils, the most common leukocyte recruited to periodontal pockets (Delima & Van Dyke, 2003; Hajishengallis et al., 2016), P. gingivalis inhibits an antimicrobial Toll-like receptor (TLR)2–MyD88 pathway through proteasomal degradation of MyD88, whereas it stimulates a proinflammatory TLR2–phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway (Maekawa et al., 2014). The TLR2–PI3K pathway additionally suppresses RhoA GTPase-dependent actin polymerization and blocks phagocytosis in both human and mouse neutrophils (Maekawa et al., 2014). These subversive pathways strictly require an intimate crosstalk between TLR2 and C5aR1 (Maekawa et al., 2014).

Though minimally present in periodontal pockets, macrophages can readily encounter periodontal bacteria that have invaded into the gingival connective tissue (Delima & Van Dyke, 2003). In this regard, the generation of nitric oxide is a key effector molecule enabling the intracellular killing of pathogens by the macrophage (Nathan, 2006). Intriguingly, P. gingivalis can interfere with this antimicrobial function by inhibiting the expression of the inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) through a cAMP- and protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent mechanism (Wang et al., 2010). Maximal induction of the cAMP response requires functional co-association and activation of three receptors, TLR2, C5aR1, and chemokine C-X-C receptor 4, by P. gingivalis (Hajishengallis et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010). Pharmacological blockade of C5aR1 leads to significantly diminished levels of intracellular cAMP and greatly facilitates the killing of P. gingivalis (Wang et al., 2010).

Therefore, despite using different mechanisms in neutrophils and macrophages, P. gingivalis exploits C5aR1 to evade killing by these leukocytes. In macrophages, P. gingivalis additionally induces TLR2 inside-out signaling that transactivates the high-affinity binding state of complement receptor 3 (CD11b/CD18), thereby allowing P. gingivalis to bind CR3 via its FimA fimbriae for a relatively safe entry into macrophages (Hajishengallis et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007). Indeed, when macrophages phagocytose P. gingivalis by alternative receptors (i.e., when CR3 is pharmacologically blocked or genetically ablated), their intracellular killing capacity is markedly potentiated (Wang et al., 2007). These findings are consistent with observations that CR3 is not linked to vigorous microbicidal mechanisms (Lowell, 2006; Vieira et al., 2002).

In this paper, we determined whether P. gingivalis uses receptors of the complement system, including C5aR1 or CR3, to manipulate dendritic cells, specialized antigen-presenting cells that internalize and process microbes and link innate and adaptive immunity (Pulendran, 2015). In comparison to neutrophils and macrophages, dendritic cells are not as potent in pathogen clearance (Silva). Surprisingly, however, we found that dendritic cells were not subverted by Pg through complement receptors, which actually facilitated the intracellular killing of Pg.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Human or mouse C5a and mouse C3a were purchased from R&D Systems. A C5aR1 antagonist (C5aR1A; PMX53), the cyclic hexapeptide Ac-F[OP(D)Cha-WR] (acetylated phenylalanine–[ornithyl-proline-(D)cyclohexylalanine-tryptophyl-arginine]) was synthesized as previously described (Finch et al., 1999). A mAb to CD11b (clone M1/70) and its isotype controls obtained from eBioscience. Cytochalasin D was from Sigma-Aldrich. Reagents used for cell culture and differentiations are mentioned in the relevant subsection. All reagents were used at optimal concentrations determined in preliminary experiments or published studies by our group (Hajishengallis et al., 2006; Liang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010).

Cell isolation and culture

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) were generated as we previously described (Liang et al., 2009) based on the original method developed by Lutz et al (Lutz et al., 1999). Briefly, bone marrow cells harvested from femur and tibia of 8-12-week-old mice were plated at 2×105 cells/ml and cultured at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere, in complete RPMI (RPMI 1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 100 units/ml penicillin G, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol; Life Technologies) supplemented with 20 ng/ml recombinant murine GM-CSF (Peprotech). The nonadherent cells were harvested on day 8 and purified by positive selection using anti-CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). For killing assays, the generated BMDC were cultured in complete RMPI without the antibiotics. Thioglycolate-elicited macrophages were isolated from the peritoneal cavity of C57BL/6 mice (The Jackson Laboratory), as previously described (Hajishengallis et al., 2005b). DC1.2 cells, a mouse dendritic cell line (Shen et al., 1997), were kindly provided by Dr. Kenneth Rock (University of Massachusetts Medical School). Cells were cultured in complete RPMI at 37°C and 5% CO2 atmosphere. Human monocytes were purified from peripheral blood upon centrifugation over NycoPrep 1.068, and incidental nonmonocytes were magnetically depleted as previously described (Harokopakis et al., 2006). To generate monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM), monocytes were incubated in complete RPMI medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml recombinant (r)GM-CSF (Pepro Tech) for 6 days (van der Does et al., 2010). Monocyte-derived DCs (MDDC) were generated as described by Jotwani et al (Jotwani et al., 2001). Briefly, monocytes were incubated in complete RPMI medium supplemented with 100 ng/ml rGM-CSF and 25 ng/ml rIL-4 (Pepro Tech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 6–8 days. After confirming the immature DC phenotype by flow cytometry (CD14−CD83−CD1a+), the cells were used in the assays. Cell viability was monitored using the CellTiter-Blue™ assay kit (Promega). None of the experimental treatments affected cell viability compared to medium-only control treatments. Human blood collections were conducted in compliance with established guidelines approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Mice

To generate BMDC, the bone marrow was obtained from wild-type or Tlr2−/− C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory) as well as from C3ar−/−, C5ar1−/− or C5ar2−/− (C5L2−/−) mice, supplied from our colonies maintained at The Jackson Laboratory. The C3ar−/− mice were originally from Dr. Rick A. Wetsel (University of Texas) (Drouin et al., 2002). The C5ar1−/− and C5ar2−/− were originally provided by Dr. Craig Gerard (Harvard Medical School) (Gerard et al., 2005; Hopken et al., 1996). All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in compliance with established federal and state policies.

Intracellular survival assay

P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 was grown anaerobically from frozen stocks on modified Gifu anaerobic medium (GAM)-based blood agar plates for 5-6 days at 37°C, followed by anaerobic subculturing for 18-24 hours at 37°C in modified GAM broth containing 5 μg/ml hemin and 1 μg/ml menadione (Nissui Pharmaceutical). The viability of phagocytosed P. gingivalis was monitored by an antibiotic protection-based intracellular survival assay, essentially as we previously described (Wang et al., 2007). Briefly, mammalian cells (BMDC, MDDC, or MDM) were allowed to phagocytose P. gingivalis (MOI = 10:1; 5×106 bacteria and 5×105 mammalian cells) for 30 min at 37°C. Extracellular nonadherent bacteria were removed by washing, while residual or extracellular adherent bacteria were killed by addition of gentamicin (300 μg/ml) and metronidazole (200 μg/ml) for 1 h. Immediately after, the cells were washed and lysed in sterile distilled water (20-min treatment at room temperature). Serial dilutions of the cell lysates were plated on blood agar plates and cultured anaerobically to determine viable counts (CFU) of internalized P. gingivalis. In certain experiments, the cells were incubated in the presence of C3a (200 nM), C5a (50 nM) and/or C5aR1A (1 μM), which was added 30 min prior to addition of Pg.

Flow cytometric internalization assay

Flow cytometry was used to measure phagocytosis of Pg as previously described (Wang et al., 2007). Briefly, BMDC or peritoneal macrophages were incubated at 37°C with FITC-labeled Pg at a MOI of 10:1 for 30 min, at which time phagocytosis was stopped by cooling the incubation tubes on ice. After cell washing to remove nonadherent bacteria, extracellular fluorescence (representing attached but not internalized bacteria) was quenched with 0.2% trypan blue. The cells were washed again, fixed, and analyzed by flow cytometry (% positive cells for FITC-P. gingivalis and mean fluorescence intensity) using flow cytometry. Control experiments indicated that cytochalasin D-pretreated cells incubated with FITC-P. gingivalis and subsequently exposed to trypan blue did not show significant fluorescence, thus confirming that cytochalasin D blocks internalization and that trypan blue quenches extracellular fluorescence. The phagocytosis index was calculated using the formula (% positive cells x MFI)/100.

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated by analysis of variance and the Dunnett multiple-comparison test using the GraphPad Prism program, version 6.0h (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Where appropriate (comparison of two groups only), two-tailed t tests were also performed. Statistical differences were considered significant at the level of p < 0.05. All experiments were performed at least twice for verification.

RESULTS

C5a enhances the intracellular killing of Pg by BMDC in a C5aR1-dependent way

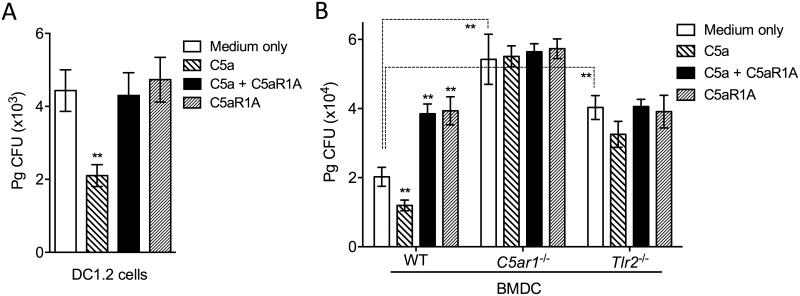

Having established that Pg exploits C5aR1 to protect itself against killing by neutrophils and macrophages (Maekawa et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2010), we set out to determine whether this oral bacterium promotes its survival in DC by hijacking the same receptor. Using a standard intracellular survival assay that established the ability of Pg to persist within macrophages (Wang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007), we showed that viable Pg could be recovered from DC1.2 cells (Fig. 1A), a validated murine DC line (Shen et al., 1997), consistent with earlier findings that Pg can survive within human myeloid DCs (Carrion et al., 2012). Intriguingly, addition of C5a to the DC1.2 cells resulted in reduced Pg viable counts (P < 0.01; Fig. 1A), whereas the same treatment was previously shown to promote the intracellular survival of Pg in mouse macrophages (Wang et al., 2010). The inhibitory effect of C5a on Pg survival was abrogated when DC1.2 cells were pre-treated with an antagonist of C5aR1 (C5aR1A) (Fig. 1A). The ability of exogenously added C5a to promote the intracellular killing of Pg was confirmed using primary cells, specifically bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDC) (Fig. 1B). In these experiments, we used BMDC from WT, C5ar1−/−, and Tlr2−/− mice to better understand the involvement of these innate immune receptors in the handling of Pg by BMDC. Interestingly, Pg showed a decrease in intracellular viable counts in WT BMDC as compared to C5ar1−/− BMDC (P < 0.01; Fig. 1B), which is likely attributed to the endogenous synthesis of C5 and generation of C5a in BMDC cultures (Peng et al., 2009) (hence, endogenous C5a can contribute to the killing of Pg in WT but not in in C5ar1−/− BMDC). In line with this finding, the antagonistic blockade of C5aR1 in WT BMDC promoted the intracellular survival of Pg (P < 0.01; Fig. 1B). As expected, treatments of C5ar1−/− BMDC with C5a and/or C5aR1A did not influence the Pg viable counts (Fig. 1B), confirming that the effects of these treatments strictly require the presence of C5aR1 and do not involve possible off-target effects. Pg displayed increased survival also in Tlr2−/− BMDC (as compared to WT BMDC) (P < 0.01; Fig. 1). Therefore, in addition to C5aR, TLR2 also contributes to the intracellular killing of Pg in BMDC.

Figure 1. C5a promotes the intracellular killing of Pg by mouse dendritic cells in a C5aR1-dependent manner.

DC1.2 cells (A) or BMDC generated from WT, C5ar1−/−, or Tlr2−/− mice (B) were incubated with Pg (MOI = 10:1) in the presence or absence of C5a (50 nM) and/or C5aR1A (1 μM). Using an antibiotic protection-based intracellular survival assay, viable counts of internalized bacteria at 90 min post-infection were determined by CFU enumeration. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments or between indicated groups.

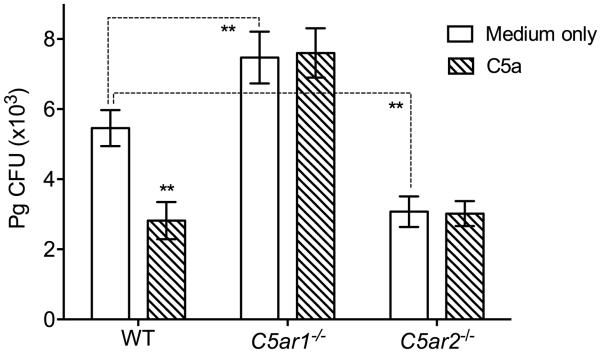

C5aR2 and C5aR1 differentially affect the intracellular survival of Pg in BMDC

We then addressed whether other complement anaphylatoxin receptors share the capacity of C5aR1 to contribute to the intracellular killing of Pg in BMDC. C5aR2 (also referred to as C5a-like receptor 2; GPR77) functions as an alternative high-affinity receptor for C5a (Monk et al., 2007). In side-by-side experiments, using WT and C5ar1−/− BMDC as comparative controls, we found that the ability of Pg to survive intracellularly in C5ar2−/− BMDC was significantly reduced compared to WT BMDC, that is, C5aR2 deficiency had the exact opposite effect from that of C5aR1 deficiency (Fig. 2). This finding is consistent with the notion that C5aR2 acts as a negative modulator of C5aR1 (Bamberg et al., 2010), which would therefore be more active in C5ar2−/− BMDC to mediate Pg killing. As expected, the intracellular survival of Pg in C5ar2−/− BMDC was not affected by the addition or not of exogenous C5a in the cultures (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. C5aR2 and C5aR1 mediate opposite effects on the intracellular survival of Pg in BMDC.

BMDC generated from WT, C5ar1−/−, or C5ar2−/− mice were incubated with Pg (MOI = 10:1) in the presence or absence of C5a (50 nM). Using an antibiotic protection-based intracellular survival assay, viable counts of internalized bacteria at 90 min post-infection were determined by CFU enumeration. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments or between indicated groups.

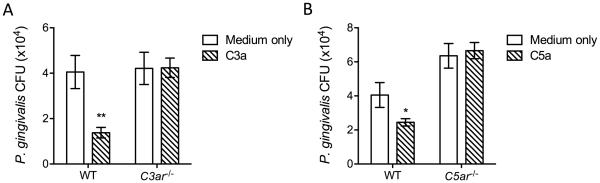

C3a enhances the intracellular killing of Pg by BMDC a C3aR-dependent manner

In a further side-by-side experiment comparing the effect of C5aR1 with that of the C3a receptor (C3aR), we showed that – similarly to C5a – C3a also promoted the killing of Pg in WT BMDC (Fig. 3). C3a failed to modulate the killing of Pg in C3ar−/− BMDC (Fig. 3), thereby firmly establishing that the effect of C3a was specifically mediated by the C3aR.

Figure 3. C3a enhances the intracellular killing of Pg by BMDC a C3aR-dependent manner.

BMDC generated from WT, C3ar−/− (A) or C5ar1−/− (B) mice were incubated with Pg (MOI = 10:1) in the presence or absence of C3a (200 nM) or C5a (50 nM), respectively. Using an antibiotic protection-based intracellular survival assay, viable counts of internalized bacteria at 90 min post-infection were determined by CFU enumeration. The experiments were performed side-by-side and the medium-only treated WT group was common to both A and B. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments.

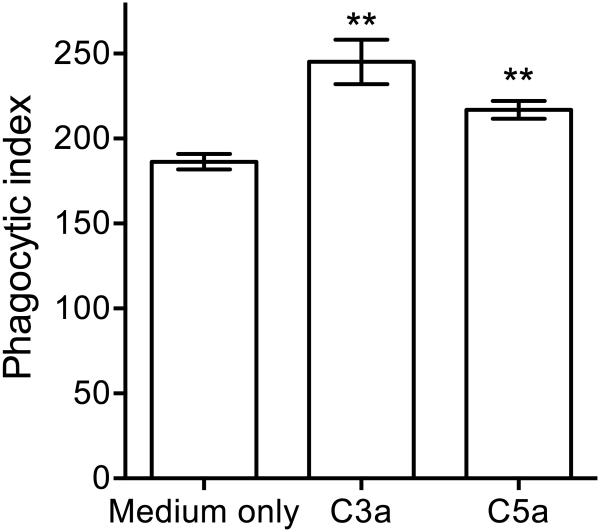

The reduced intracellular viable counts of Pg in the presence of C3a or C5a might – at least in part – be attributed to decreased Pg phagocytosis by BMDC. This possibility was ruled out after we measured Pg phagocytosis by BMDC in the absence or presence of C3a or C5a. Indeed, none of the anaphylatoxins inhibited Pg phagocytosis but rather modestly- albeit significantly- promoted this function (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4). Therefore, C3a and C5a promote the phagocytosis and killing of Pg by BMDC.

Figure 4. C3a and C5a enhance the phagocytosis of Pg by BMDC.

BMDC were incubated for 30 min with FITC-labeled Pg and phagocytosis was determined by flow cytometry after quenching extracellular fluorescence. The phagocytic index was calculated using the formula (% positive cells x MFI)/100. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments.

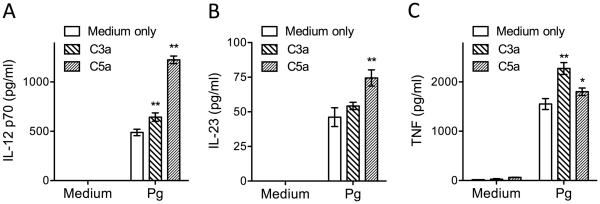

C3a and C5a upregulate cytokine production in Pg-challenged BMDC

We have previously shown that C5a inhibits Pg-induced IL-12p70 in mouse macrophages, resulting in enhanced in vivo survival of Pg in the mouse host (Liang et al., 2011). In view of the stimulatory effects of C5a (and C3a) on Pg killing in BMDC, we determined the effects of C5a and C3a on the induction of IL-12p70 in Pg-challenged BMDC. In contrast to the results obtained in macrophages, C5a enhanced Pg-induced IL-12p70 in BMDC (Fig. 5). C3a exerted a similar but less pronounced effect (Fig. 5). C5a also enhanced the production of IL-23, while C3a and C5a augmented the production of TNF by Pg-challenged BMDC (Fig. 5), thereby firmly establishing that they exert stimulatory, and not immunosuppressive, effects in BMDC.

Figure 5. C3a and C5a promote induction of proinflammatory cytokines in Pg-challenged BMDC.

BMDC were incubated with medium only or with Pg (MOI = 10:1) and the levels of the indicated cytokines in culture supernatants, collected at 24h post-incubation, were determined by ELISA. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments.

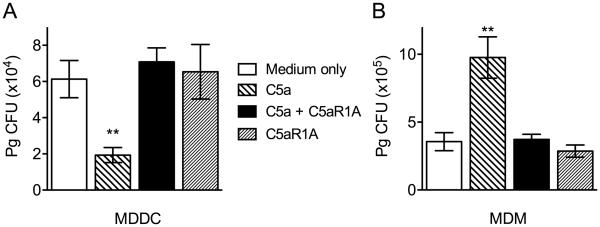

Differential effects of C5aR1 on Pg intracellular viability in human MDDC and MDM

We next examined whether the Pg killing-promoting effect of the C5a-C5aR1 axis is relevant to human myeloid dendritic cells. Consistent with the data in the mouse system (Fig. 1), C5a significantly enhanced the killing of Pg by human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (MDDC), whereas C5aR1A reversed this effect (Fig. 6A). In stark contrast, C5a enhanced the intracellular survival of Pg in human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) in a C5aR1-dependent manner (Fig. 6B), consistent with our earlier observations in mouse macrophages (Wang et al., 2010). These data show that the cell-type specific effect of C5aR1 on Pg intercellular killing is not species-restricted in its mode of action.

Figure 6. Differential effects of the C5a-C5aR1 axis on the intracellular survival of Pg in human MDDC vs. MDM.

MDDC (A) or MDM were incubated with Pg (MOI = 10:1) in the presence or absence of C5a (50 nM) and/or C5aR1A (1 μM). Using an antibiotic protection-based intracellular survival assay, viable counts of internalized bacteria at 90 min post-infection were determined by CFU enumeration. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments.

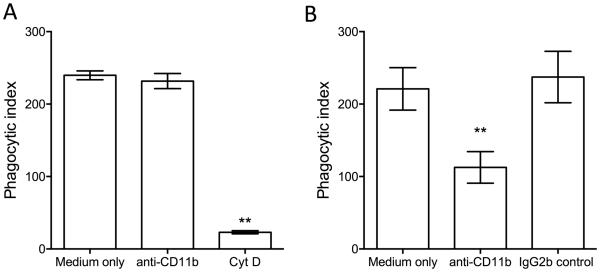

Pg fails to utilize CR3 in BMDC

We have previously shown that Pg uses complement receptor 3 (CR3; CD11b/CD18) to enter and persist within mouse macrophages (Wang et al., 2007). Although Pg failed to exploit C3aR or C5a1R in BMDC to enhance its survival, we set out to determine whether the observed intracellular viability of Pg could be attributed, at least in part, to exploitation of CR3 in BMDC. We first determined whether BDMC CR3 functions as a phagocytic receptor for Pg. However, a CR3 blocking mAb failed to inhibit the phagocytosis of Pg by BMDC (Fig. 7A), whereas the same mAb blocked the phagocytosis of Pg by mouse macrophages (Fig. 7B). Therefore, CR3 is not a phagocytic receptor for Pg in BMDC.

Figure 7. CR3 does not mediate Pg phagocytosis by BMDC.

BMDC (A) or macrophages (B) were incubated for 30 min with FITC-labeled Pg, in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml mAb to CD11b (CR3). Cytochalasin D (10 μg/ml) was used as positive control for phagocytosis inhibition in A. IgG2b was used as isotype control in B. Phagocytosis was determined by flow cytometry after quenching extracellular fluorescence. The phagocytic index was calculated using the formula (% positive cells x MFI)/100. Data are means ± SD (n=3 sets of cell cultures). **P < 0.01 compared to medium-only control treatments.

DISCUSSION

Our findings from this study show a context-dependent involvement of complement receptors in immune evasion by Pg. Although Pg can exploit C5aR1 in neutrophils and macrophages to undermine their antimicrobial function (Maekawa et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2010) as well as hijack CR3 for a safe entry into macrophages (Wang et al., 2007), the same receptors on dendritic cells did not provide a survival advantage to Pg. In fact, C5aR1 facilitated the intracellular killing of Pg in dendritic cells, whereas CR3 did not function as a phagocytic receptor for Pg. Similar to C5aR1, C3aR enhanced the intracellular killing of Pg in dendritic cells, although in macrophages C3aR had no significant effect on the intracellular survival of Pg (Wang et al., 2010). Thus, differences in signaling pathways between the various innate leukocytes may account for the distinct intracellular fate of Pg.

For instance, the diametrically opposed effects of C5aR1 in dendritic cells and macrophages (promoting intracellular killing of Pg in dendritic cells, but enhancing intracellular survival of Pg in macrophages) might be related to differential regulation of the cAMP response in these two cell types. In macrophages, activation of C5aR1 leads to increased levels of intracellular cAMP and hence PKA activation, which is critical for suppressing the nitric oxide-dependent killing of Pg (Wang et al., 2010). Interestingly, C5aR1 signaling stimulates cAMP-dependent PKA activity also in neutrophils (Ward, 2004). In dendritic cells, however, C5aR1 was shown to inhibit cAMP production and thus the activation of PKA (Peng et al., 2009). C3aR – which also promoted BMDC killing of Pg in this study – was also shown to inhibit the cAMP-PKA pathway, thereby lifting regulatory restraints on dendritic cell activation (Li et al., 2008). Both C3aR and C5aR1 activate Gαi protein-mediated signaling. Upon Gαi activation, the released Giβγ subunits regulate the production of cAMP by adenylate cyclase, either in a positive or negative manner, depending on the enzyme isoform (Sunahara & Taussig, 2002). Interestingly, the adenylate cyclase isoforms that are positively regulated by Giβγ are distinct from those that are sensitive to the inhibitory action of Gαi (Sunahara & Taussig, 2002). Thus, it is possible that dendritic cells and macrophages express different isoforms of adenylate cyclase, which in turn display differential regulation in response to C3aR- or C5aR-induced Gαi signaling.

Another cell type-specific difference we have observed in this study is that C5a promotes Pg-induced IL-12p70 in BMDC, whereas previously we have shown that the same ligand inhibits Pg-induced IL-12p70 in macrophages (Liang et al., 2011). The C5a-induced inhibition of IL-12p70 by Pg was mediated by ERK1/2 signaling (Liang et al., 2011), in line with earlier studies showing that C5a-induced ERK1/2 signaling inhibits enterobacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-12p70 production (Hawlisch et al., 2005). Whereas C5a was shown to induce ERK1/2 signaling also in dendritic cells (Weaver et al., 2010), the ERK1/2 pathway in this cell type upregulates, rather than inhibits, IL-12p70 production (Baruah et al., 2009).

C5aR2 is a relatively recently discovered C5a receptor, the function of which is largely enigmatic, if not controversial. Although originally perceived as a decoy receptor (Okinaga et al., 2003), subsequent studies showed that C5aR2 interacts physically with and negatively regulates C5aR1 signaling, thereby having anti-inflammatory action (Bamberg et al., 2010; Croker et al., 2014; Gerard et al., 2005). Yet, other studies have assigned a proinflammatory role for C5aR2 in various experimental systems and disease models (Pundir et al., 2015; Rittirsch et al., 2008; Selle et al., 2015). Overall, it appears that the activities of C5aR2 are dynamic and contextual depending on cell type, tissue, and disease model (Li et al., 2013). Our findings that C5aR1 promotes the intracellular killing of Pg in BMDC, whereas the absence of C5aR2 is associated with increased intracellular viable counts of Pg is consistent with the notion that C5aR2 acts as a negative regulator of C5aR1 (Bamberg et al., 2010; Croker et al., 2014).

Although Pg does not appear to exploit complement receptors (at least not those investigated here) to survive in dendritic cells, earlier work has shown that Pg can exploit other innate immune mechanisms to manipulate this cell type. Specifically, Pg uses its Mfa1 fimbriae to interact with a C-type lectin, the dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 grabbing nonintegrin (DC-SIGN) (Zeituni et al., 2009). Through this interaction, Pg enters dendritic cells and promotes its survival while suppressing the maturation of the dendritic cells (Carrion et al., 2012; Zeituni et al., 2009). Interestingly, whereas DC-SIGN directs Pg into intracellular vesicles that escape early autophagosomal recognition and eventual autophagic degradation, TLR2 antagonizes autophagy evasion and thus the intracellular persistence of Pg (El-Awady et al., 2015). Consistent with this finding, we found that that Pg exhibited increased viable counts in Tlr2−/− BMDC as compared to WT BMDC, thus indicating that TLR2 contributes to the intracellular killing of Pg. By using different fimbrial mutants of Pg that preferentially interact with DC-SIGN (Mfa1+FimA–) or TLR2 (Mfa1–FimA+), the same group showed that the Mfa1+FimA– strain displays increased intracellular survival than the WT strain, which in turn is more resistant to intracellular killing than the Mfa1–FimA+ strain (El-Awady et al., 2015). This earlier study in conjunction with our current findings suggest that DC-SIGN promotes the intracellular survival of Pg in dendritic cells, whereas TLR2 and complement receptors (C3aR and C5aR1) mediate the opposite effect, thus facilitating the clearance of Pg.

The association of the TLR2-interacting FimA fimbriae with increased intracellular killing in myeloid dendritic cells stands in stark contrast to the ability of the same fimbrial protein to mediate Pg evasion in macrophages (Wang et al., 2007). In macrophages, activation of TLR2 by Pg leads to inside-out signaling that transactivates CR3 to adopt its high-affinity conformation (Harokopakis & Hajishengallis, 2005). Pg FimA fimbriae can then bind transactivated CR3 (through distinct FimA epitopes from those activating TLR2 (Hajishengallis et al., 2005a)) leading to the internalization of Pg in a manner that avoids lysosomal degradation (Wang & Hajishengallis, 2008; Wang et al., 2007). In contrast, Pg failed to utilize CR3 at in BMDC. The reason for this difference is not clear. However, as alluded to above, CR3 and other β2 integrins require transactivation via inside-out signaling to adopt their high-affinity conformation (Shimaoka et al., 2002). In dendritic cells, β2 integrins including CR3 (CD11b/CD18; Mac-1) appear to be functionally inactive, as they cannot be readily activated by various physiologic stimuli (Varga et al., 2007). CR3 activation could be achieved when supraphysiologic concentrations (5 mM) of Mg2+ were used (Varga et al., 2007). Our results here, therefore, are consistent with and support this earlier observation (Varga et al., 2007) and, taken together with our earlier findings (Wang et al., 2007), show that Pg can transactivate and utilize CR3 in macrophages but not in dendritic cells.

In summary, complement receptors, such as C3aR, C5aR1, and CR3, mediate cell-type-specific effects on how innate leukocytes cope with Pg. Specifically, Pg exploits complement to promote its adaptive fitness in neutrophils and macrophages, but not in dendritic cells, where C3aR and C5aR1 actually facilitate the intracellular killing of this bacterium. These findings appear paradoxical given the fact that dendritic cells are not as potent in pathogen destruction as compared to neutrophils or macrophages (Silva). However, the immediate threat to Pg in its predominant niche, the periodontal pocket, is represented by neutrophils and secondarily by macrophages (these two cell types and especially the former predominate in the leukocyte infiltrate of the periodontal pocket (Delima & Van Dyke, 2003). Therefore, and given the abundance of complement activation products in the periodontal pocket (Hajishengallis, 2010), it makes evolutionary sense that Pg developed complement-dependent evasion mechanisms against the leukocyte types that are most often encountered in its niche.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (DE015254 and DE021685 to G.H; AI068730 and AI030040 to J.D.L.).

REFERENCES

- Abusleme L, Dupuy AK, Dutzan N, et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 2013;7:1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg CE, Mackay CR, Lee H, et al. The C5a receptor (C5aR) C5L2 is a modulator of C5aR-mediated signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7633–7644. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruah P, Dumitriu IE, Malik TH, et al. C1q enhances IFN-g production by antigen-specific T cells via the CD40 costimulatory pathway on dendritic cells. Blood. 2009;113:3485–3493. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-164392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostanci N, Belibasakis GN. Porphyromonas gingivalis: an invasive and evasive opportunistic oral pathogen. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2012;333:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion J, Scisci E, Miles B, et al. Microbial carriage state of peripheral blood dendritic cells (DCs) in chronic periodontitis influences DC differentiation, atherogenic potential. J Immunol. 2012;189:3178–3187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croker DE, Halai R, Kaeslin G, et al. C5a2 can modulate ERK1/2 signaling in macrophages via heteromer formation with C5a1 and beta-arrestin recruitment. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:631–639. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darveau RP. The oral microbial consortium's interaction with the periodontal innate defense system. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:389–395. doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darveau RP, Hajishengallis G, Curtis MA. Porphyromonas gingivalis as a potential community activist for disease. J Dent Res. 2012;91:816–820. doi: 10.1177/0022034512453589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delima AJ, Van Dyke TE. Origin and function of the cellular components in gingival crevice fluid. Periodontol 2000. 2003;31:55–76. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2003.03105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin SM, Corry DB, Hollman TJ, Kildsgaard J, Wetsel RA. Absence of the complement anaphylatoxin C3a receptor suppresses Th2 effector functions in a murine model of pulmonary allergy. J Immunol. 2002;169:5926–5933. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Awady AR, Miles B, Scisci E, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis evasion of autophagy and intracellular killing by human myeloid dendritic cells involves DC-SIGN-TLR2 crosstalk. PLoS Pathog. 2015;10:e1004647. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch AM, Wong AK, Paczkowski NJ, et al. Low-molecular-weight peptidic and cyclic antagonists of the receptor for the complement factor C5a. J Med Chem. 1999;42:1965–1974. doi: 10.1021/jm9806594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerard NP, Lu B, Liu P, et al. An anti-inflammatory function for the complement anaphylatoxin C5a-binding protein, C5L2. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39677–39680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C500287200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G. Complement and periodontitis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1992–2001. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Darveau RP, Curtis MA. The keystone-pathogen hypothesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:717–725. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lambris JD. Microbial manipulation of receptor crosstalk in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:187–200. doi: 10.1038/nri2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Beyond the red complex and into more complexity: The Polymicrobial Synergy and Dysbiosis (PSD) model of periodontal disease etiology. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2012;27:409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-1014.2012.00663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Breaking bad: Manipulation of the host response by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:328–338. doi: 10.1002/eji.201344202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Lamont RJ. Dancing with the Stars: how Choreographed Bacterial Interactions Dictate Nososymbiocity and Give Rise to Keystone Pathogens, Accessory Pathogens, and Pathobionts. Trends Microbiol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.02.010. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.02.010. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Liang S, Payne MA, et al. Low-abundance biofilm species orchestrates inflammatory periodontal disease through the commensal microbiota and complement. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:497–506. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Moutsopoulos NM, Hajishengallis E, Chavakis T. Immune and regulatory functions of neutrophils in inflammatory bone loss. Semin Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.02.002. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2016.02.002. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Ratti P, Harokopakis E. Peptide mapping of bacterial fimbrial epitopes interacting with pattern recognition receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005a;280:38902–38913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Tapping RI, Martin MH, et al. Toll-like receptor 2 mediates cellular activation by the B subunits of type II heat-labile enterotoxins. Infect Immun. 2005b;73:1343–1349. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.3.1343-1349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Wang M, Harokopakis E, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K. Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae proactively modulate β2 integrin adhesive activity and promote binding to and internalization by macrophages. Infect Immun. 2006;74:5658–5666. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00784-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishengallis G, Wang M, Liang S, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K. Pathogen induction of CXCR4/TLR2 cross-talk impairs host defense function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:13532–13537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803852105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harokopakis E, Albzreh MH, Martin MH, Hajishengallis G. TLR2 transmodulates monocyte adhesion and transmigration via Rac1- and PI3K-mediated inside-out signaling in response to Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. J Immunol. 2006;176:7645–7656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harokopakis E, Hajishengallis G. Integrin activation by bacterial fimbriae through a pathway involving CD14, Toll-like receptor 2, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1201–1210. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawlisch H, Belkaid Y, Baelder R, Hildeman D, Gerard C, Kohl J. C5a negatively regulates toll-like receptor 4-induced immune responses. Immunity. 2005;22:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong BY, Furtado Araujo MV, Strausbaugh LD, Terzi E, Ioannidou E, Diaz PI. Microbiome profiles in periodontitis in relation to host and disease characteristics. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127077. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopken UE, Lu B, Gerard NP, Gerard C. The C5a chemoattractant receptor mediates mucosal defence to infection. Nature. 1996;383:86–89. doi: 10.1038/383086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jotwani R, Palucka AK, Al-Quotub M, et al. Mature dendritic cells infiltrate the T cell-rich region of oral mucosa in chronic periodontitis: In Situ, in vivo, and in vitro studies. J Immunol. 2001;167:4693–4700. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.8.4693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambris JD, Ricklin D, Geisbrecht BV. Complement evasion by human pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:132–142. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamont RJ, Hajishengallis G. Polymicrobial synergy and dysbiosis in inflammatory disease. Trends Mol Med. 2015;21:172–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2014.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li K, Anderson KJ, Peng Q, et al. Cyclic AMP plays a critical role in C3a-receptor-mediated regulation of dendritic cells in antigen uptake and T-cell stimulation. Blood. 2008;112:5084–5094. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Coulthard LG, Wu MC, Taylor SM, Woodruff TM. C5L2: a controversial receptor of complement anaphylatoxin, C5a. FASEB J. 2013;27:855–864. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-220509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Hosur KB, Nawar HF, Russell MW, Connell TD, Hajishengallis G. In vivo and in vitro adjuvant activities of the B subunit of Type IIb heat-labile enterotoxin (LT-IIb-B5) from Escherichia coli. Vaccine. 2009;27:4302–4308. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang S, Krauss JL, Domon H, et al. The C5a receptor impairs IL-12-dependent clearance of Porphyromonas gingivalis and is required for induction of periodontal bone loss. J Immunol. 2011;186:869–877. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowell CA. Rewiring phagocytic signal transduction. Immunity. 2006;24:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, et al. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J Immunol Methods. 1999;223:77–92. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa T, Krauss JL, Abe T, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis manipulates complement and TLR signaling to uncouple bacterial clearance from inflammation and promote dysbiosis. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk PN, Scola AM, Madala P, Fairlie DP. Function, structure and therapeutic potential of complement C5a receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:429–448. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Role of iNOS in human host defense. Science. 2006;312:1874–1875. doi: 10.1126/science.312.5782.1874b. author reply 1874-1875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okinaga S, Slattery D, Humbles A, et al. C5L2, a nonsignaling C5a binding Protein. Biochemistry. 2003;42:9406–9415. doi: 10.1021/bi034489v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q, Li K, Wang N, et al. Dendritic cell function in allostimulation is modulated by C5aR signaling. J Immunol. 2009;183:6058–6068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulendran B. The varieties of immunological experience: of pathogens, stress, and dendritic cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:563–606. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pundir P, MacDonald CA, Kulka M. The Novel Receptor C5aR2 Is Required for C5a-Mediated Human Mast Cell Adhesion, Migration, and Proinflammatory Mediator Production. J Immunol. 2015;195:2774–2787. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricklin D, Hajishengallis G, Yang K, Lambris JD. Complement: a key system for immune surveillance and homeostasis. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:785–797. doi: 10.1038/ni.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Nadeau BA, et al. Functional roles for C5a receptors in sepsis. Nat Med. 2008;14:551–557. doi: 10.1038/nm1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selle J, Asare Y, Kohncke J, et al. Atheroprotective role of C5ar2 deficiency in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114:848–858. doi: 10.1160/TH14-12-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Reznikoff G, Dranoff G, Rock KL. Cloned dendritic cells can present exogenous antigens on both MHC class I and class II molecules. The Journal of Immunology. 1997;158:2723–2730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimaoka M, Takagi J, Springer TA. Conformational regulation of integrin structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2002;31:485–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.31.101101.140922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva MT. When two is better than one: macrophages and neutrophils work in concert in innate immunity as complementary and cooperative partners of a myeloid phagocyte system. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:93–106. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunahara RK, Taussig R. Isoforms of mammalian adenylyl cyclase: Multiplicities of signaling. Mol Interv. 2002;2:168–184. doi: 10.1124/mi.2.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Does AM, Beekhuizen H, Ravensbergen B, et al. LL-37 directs macrophage differentiation toward macrophages with a proinflammatory signature. J Immunol. 2010;185:1442–1449. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varga G, Balkow S, Wild MK, et al. Active MAC-1 (CD11b/CD18) on DCs inhibits full T-cell activation. Blood. 2007;109:661–669. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-023044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira OV, Botelho RJ, Grinstein S. Phagosome maturation: aging gracefully. Biochem J. 2002;366:689–704. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Hajishengallis G. Lipid raft-dependent uptake, signalling and intracellular fate of Porphyromonas gingivalis in mouse macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2029–2042. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Krauss JL, Domon H, et al. Microbial hijacking of complement-toll-like receptor crosstalk. Sci Signal. 2010;3:ra11. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M, Shakhatreh MA, James D, et al. 2007) Fimbrial proteins of Porphyromonas gingivalis mediate in vivo virulence and exploit TLR2 and complement receptor 3 to persist in macrophages. J Immunol. 179:2349–2358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PA. The dark side of C5a in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:133–142. doi: 10.1038/nri1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward PA. Functions of C5a receptors. J Mol Med. 2009;87:375–378. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0442-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver DJ, Jr., Reis ES, Pandey MK, et al. C5a receptor-deficient dendritic cells promote induction of Treg and Th17 cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:710–721. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz O. The chronicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis: the microbium, the human oral epithelium and their interplay. Microbiology. 2008;154:2897–2903. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/021220-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeituni AE, Jotwani R, Carrion J, Cutler CW. Targeting of DC-SIGN on human dendritic cells by minor fimbriated Porphyromonas gingivalis strains elicits a distinct effector T cell response. J Immunol. 2009;183:5694–5704. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]