Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an emerging chronic inflammatory disease that affects both children and adults [1]. The disease is characterized by signs and symptoms of esophageal dysmotility from underlying chronic inflammation of the esophagus. Histologically, EoE is characterized by eosinophilic infiltration into the esophagus that persists after a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial. Chronic inflammation leads to histologic remodeling of the esophagus inclusive of fibrosis, rings, linear furrows, and stricture formation [2]. Symptoms vary between children and adults; while children tend to present with vomiting, abdominal pain and/or failure to thrive, adults often complain of dysphagia, food impaction and heartburn.

The hypothesis that foods are triggers for EoE has been supported by the success of various food elimination diets. Since the first description of a successful food elimination diet in 1995 [3], many additional studies have validated these findings. EoE resolution rates in children treated with an amino acid based diet are 96% or higher [4–6]. An elemental diet also improves endoscopic and histological features of EoE in 72% of adults [7]. Empiric 4 or 6 food elimination diets also lead to resolution of EoE in more than 70% of adult subjects [8–10], and sequential reintroduction of foods are able to uncover specific trigger foods of EoE. Although efficacious, empiric elimination diets are also often cumbersome, time consuming, costly, unpalatable (particularly an elemental diet) and may induce iatrogenic nutritional deficiencies. Thus, more targeted approaches to food elimination have been sought.

Although IgE mediated skin testing does not appear to be an accurate predictor of EoE food triggers in adults [2, 5, 11–13], we sought to determine whether the identification of food and/or aeroallergen sensitivity in EoE patients may provide other significant clinical information about the patient and/or their disease. More specifically, does the presence of food or aeroallergen sensitivity identify a distinct phenotype of adult EoE? To address this question, we performed a retrospective chart review on adult patients with EoE within our University of Wisconsin Health System clinics. With these data, we examined whether food allergen sensitivity or aeroallergen sensitivity identify distinct clinical phenotypes of EoE.

Methods

We performed an IRB approved retrospective chart review of patients with a diagnosis of EoE (based on ICD-9 codes) seen at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics during the years 2008–2013. Of the total 724 patients, 257 were seen in a University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Adult Allergy clinic. All 257 patient charts were accessed to capture demographics, atopic history, disease severity, endoscopy results, pathology reports, allergy test results, medical management and patient reported outcomes.

Patient demographic information included age at presentation, ethnicity, race and sex. History of atopic diseases was based on patient report and/or physician diagnosis as documented in the medical record. Disease severity was assessed by duration of EoE symptoms, history of emergency department visits for EoE symptoms and need for procedural interventions for EoE complications. Peripheral eosinophilia was defined as a peripheral eosinophil count of greater than 500. Endoscopy findings were obtained from a patient’s initial diagnostic upper endoscopy procedure note. Eosinophils per high-powered field were recorded based on patient endoscopic esophageal pathology report. If multiple eosinophil counts were recorded, the highest number was used. If the report stated a count of “greater than x”, it was recorded as such. A patient’s medical management for EoE was based on documentation from the initial visit in the Allergy clinic and included medications for EoE, food avoidance strategies and procedural interventions. The pre-allergy management was based on the Allergist’s documentation of management prior to the initial Allergy clinic visit. Post-Allergy visit medical management was based on the Allergist’s documentation of recommendations at the initial encounter visit. Patient outcomes were determined by patient symptom report at a subsequent follow up visit with either Gastroenterology or Allergy. Outcomes were categorized based on subjective evaluation of the clinic visit note as “complete improvement”, “partial improvement”, “no change” or “worse”. There were a number of patients that did not return to either Gastroenterology or Allergy clinics after their initial evaluation and were listed as “lost to follow up”. If any specific information was not available for a patient, then “unknown” was recorded for that entry.

Skin prick test (SPT) results were obtained from the patient’s medical record. A positive SPT result was recorded if there was any skin reaction to testing, which included trace reactions. For those patients with indeterminate SPT due to a blunted histamine reaction or positive saline reaction, “indeterminate” was recorded. In these cases, serum specific IgE results for foods and/or aeroallergens were recorded instead, if available. If no SPT was completed, but serum specific IgE to foods and/or aeroallergens were done, then results of the serum specific IgE were recorded. Any serum specific IgE greater than 0.35 kU/ml was considered positive. Patients were categorized as either “food sensitive” or “non-food sensitive” based on food SPT and/or serum IgE results.

For statistical analyses, the chi-squared test for association was used to compare categorical characteristics or outcomes by food sensitization status and aeroallergen sensitization status. Unknowns were included in the analysis. Because eosinophil counts per high powered field were often recorded as “greater than x” and were thus right censored, they were compared between groups using a parametric lognormal survival regression model. A p-value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Of the total 257 patients seen at a University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics Adult Allergy Clinic, 155 patients (60%) were male and 102 patients (40%) were female. The average patient age was 38 years old (range 13 – 83 years). Four patients (2%) self identified as Hispanic/Latino ethnicity. The remainder of the patients that reported an ethnicity identified themselves as non-Hispanic. Most patients (97%) identified their race as white, followed by black (1%) and Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (1 patient). A majority (84%) of patients had concurrent atopic diseases such as asthma (43%), allergic rhinitis (79%), food allergy (21%) and atopic dermatitis (9%). In regards to reported food allergy, peanut/tree nut allergy was most common (35%), followed by fish/shellfish allergy (32%).

As shown in Table 1, the most commonly reported symptoms of EoE included dysphagia (81%), food impaction (58%) and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (47%). In subjects’ whose medical record documented duration of EoE symptoms, almost 90% had EoE symptoms for over 1 year. Emergency Department (ED) visits for EoE symptoms, emergency procedures for food impaction and dilations were seen in 28%, 18% and 39% of patients respectively. A majority of patients’ whose chart documented a peripheral eosinophil count did not have peripheral eosinophilia (76%). Common esophageal endoscopy findings included esophageal rings (56%), linear furrows (35%), and strictures (40%). The most common recommended treatment for EoE was swallowed steroid (74%) followed by proton pump inhibitor (70%). Food avoidance was recommended in 40% of cases, though we did not capture whether the food elimination was based on targeted recommendations from the food allergy testing or empiric elimination. Additionally, food avoidance was often recommended in addition to other medical therapies. Food avoidance as the sole treatment recommendation was only recommended in 10 patients. 32 patients were recommended to try food avoidance in addition to a PPI. In the patients with known outcomes, regardless of recommended treatment, there were no significant differences in the reports of complete improvement, partial improvement, or no change in symptoms (Figure E1).

Table 1.

EoE Clinical Characteristics

| Clinical Characteristics | Number of Patients (%) N=257 |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Dysphagia | 209 (81%) |

| Food Impaction | 148 (58%) |

| GERD | 212 (82%) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 22 (9%) |

| Abdominal Pain | 12 (5%) |

| Regurgitation | 16 (6%) |

| Chest Pain | 17 (7%) |

| Choking | 18 (7%) |

| Other | 19 (7%) |

| Duration of Symptoms | |

| <1 year | 29 (11%) |

| 1–5 years | 72 (28%) |

| 5–10 years | 30 (12%) |

| >10 years | 75 (29%) |

| Unknown | 50 (49%) |

| Severity | |

| ED Visit | 71 (28%) |

| Procedure-FI | 46 (18%) |

| Dilation | 100 (39%) |

| Peripheral Eosinophils | |

| >500 | 43 (17%) |

| <500 | 137 (53%) |

| Unknown | 77 (30%) |

| Endoscopic Findings | |

| Rings | 143 (56%) |

| Furrows | 89 (35%) |

| Strictures | 102 (40%) |

| Treatment Recommendation | |

| PPI | 179 (70%) |

| H2 Blocker | 27 (10%) |

| Swallowed Steroid | 189 (74%) |

| Oral Prednisone/Entocort | 12 (5%) |

| Montelukast | 11 (4%) |

| None | 4 (2%) |

| Food Avoidance Total (with or without other treatments | 103 (40%) |

| Food Avoidance Only | 10 (4%) |

| Food Avoidance + PPI Only | 32 (12%) |

| PPI and Swallowed Steroid | 133 (52%) |

| Any Combination of >1 Medicine | 150 (58%) |

| Reported Outcomes | |

| Partial Improvement | 39 (15%) |

| Complete Improvement | 118 (46%) |

| Worse | 4 (2%) |

| No Change | 23 (9%) |

| Unknown | 73 (28%) |

IgE-mediated testing to foods, by SPT and/or serum specific IgE, was completed for 238 (92%) of the 257 adult EoE patients. Food SPT was performed for 224 (87%) patients with nine patients having uninterpretable results due to either blunted histamine response or dermatographism. Of these nine patients, seven had food specific serum IgE testing completed in addition to the SPT and the remaining two patients had no additional testing done. Excluding these two patients without interpretable results, there were a total of 236 patients with results in the form of SPT and/or serum specific IgE. A total of 56 (22%) patients had food specific serum IgE results: 42 patients had food specific IgE done in combination with food SPT and 14 patients had food specific IgE done only.

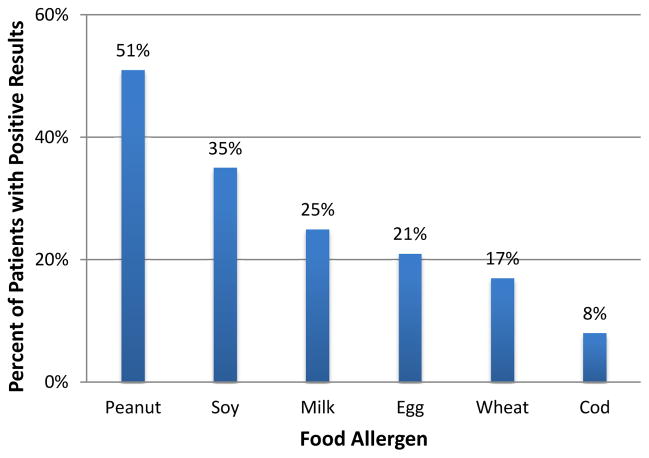

Of the 236 patients with interpretable IgE-mediated testing, 128 (54%) had a positive result to at least one food. As shown in Figure 1, of the six foods most commonly tested, peanut sensitivity was the most prevalent (51%), followed by soy (35%). Cod was the least common food sensitivity (8%). A complete list of food sensitivities is provided in the online supplement (Table E1).

Figure 1.

Food Sensitivities. The percentage of patients that exhibited a positive skin prick test or serum IgE test for the specified food allergens is shown.

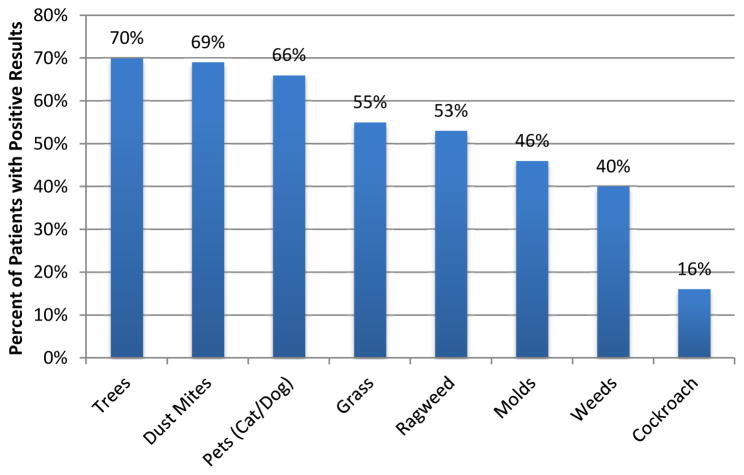

A summary of aeroallergen sensitivity results is shown in Figure 2. SPT to aeroallergens was completed for 181 (70%) of the 257 adult EoE patients of which 5 had non-interpretable results. Of the five patients with non-interpretable SPT results, two had aeroallergen serum specific IgE completed and three patients did not have any additional testing done. An additional 2 patients had serum aeroallergen specific IgE done without any SPT. Of the 180 patients with interpretable aeroallergen test results, 157 (87%) were sensitized to at least one aeroallergen. Tree, dust mite and pet (cat and/or dog) sensitivities were the most common, affecting 70%, 69% and 66% of the patients, respectively.

Figure 2.

Aeroallergen Sensitivities. The percentage of patients that exhibited a positive skin prick test or serum IgE test for the specified aeroallergens is shown.

In order to determine whether patient allergic sensitivities impact the clinical or biological characteristics of EoE, patients were stratified as food sensitive versus non-food sensitive based on food IgE-mediated testing (SPT and/or serum specific IgE) and stratified as aeroallergen sensitive versus non-aeroallergen sensitive based on aeroallergen IgE-mediated testing. As shown in Table 2, 128 patients were sensitized to at least one food and 108 patients had no food sensitivities. Patient characteristics did not differ between groups, except food sensitive patients were more likely to report concomitant asthma (p=0.01), allergic rhinitis (p=0.02), food allergy (p<0.001), or atopic dermatitis (p=0.03) compared to non-food sensitive patients. Patient reported EoE symptoms and duration of symptoms did not significantly differ between groups. Number of patients requiring ED visits for EoE signs or symptoms, emergency endoscopy for food impaction and esophageal dilations did not significantly differ between groups. Additional analyses were done to compare patients with one or more food sensitivities with a history of a true IgE mediated food allergy and patients with food sensitivities without a history of a correlating IgE mediated food allergy (online supplement Table E2). There were no statistically significant differences in patient clinical characteristics between these two groups.

Table 2.

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Stratified by Allergen Sensitivity

| Food Sensitive Patients | Aeroallergen Sensitive Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Yes (n=128) | No (n=108) | Yes (n=157) | No (n=23) |

| Symptoms | ||||

| Dysphagia | 101 (79%) | 90 (83%) | 128 (82%) | 21 (91%) |

| Food Impaction | 69 (54%) | 68 (63%) | 86 (55%) | 17 (74%) |

| GERD | 66 (52%) | 43 (40%) | 79 (50%) | 10 (43%) |

| Nausea/Vomiting | 12 (9%) | 9 (8%) | 12 (8%) | 2 (9%) |

| Abdominal Pain | 6 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 10 (6%) | 1 (4%) |

| Regurgitation | 11 (9%) | 5 (5%) | 10 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| Chest Pain | 10 (8%) | 8 (7%) | 10 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| Choking | 10 (8%) | 3 (3%) | 10 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 20 (16%) | 10 (9%) | 22 (14%) | 4 (17%) |

| Duration of Symptoms | ||||

| <1 Year | 13 (10%) | 13 (12%) | 13 (8%) | 4 (17%) |

| 1–5 Years | 29 (23%) | 37 (34%) | 42 (27%) | 6 (26%) |

| 5–10 Years | 15 (12%) | 14 (13%) | 21 (13%) | 3 (13%) |

| >10 Years | 43 (34%) | 27 (25%) | 50 (32%) | 4 (17%) |

| Unknown | 27 (21%) | 17 (16%) | 30 (19%) | 6 (26%) |

| <10 Years | 57 (44%) | 64 (59%) | 76 (48%) | 13 (57%) |

| >10 Years | 43 (34%) | 27 (25%) | 50 (32%) | 4 (17%) |

| Unknown | 27 (21%) | 17 (16%) | 30 (19%) | 6 (26%) |

| Patient Reported History of Atopic Disease | ||||

| Allergic Rhinitis | 107 (84%)* | 76 (70%) | 155 (99%)** | 11 (48%) |

| Asthma | 66 (52%)* | 37 (34%) | 80 (51%)* | 5 (22%) |

| Food Allergy | 41 (32%)** | 12 (11%) | 41 (26%) | 4 (17%) |

| Atopic Dermatitis | 16 (12%)* | 4 (4%) | 17 (11%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disease Severity | ||||

| Dilation (at any time) | 57 (44%) | 39 (36%) | 64 (41%) | 5 (22%) |

| ED | 32 (25%) | 37 (34%) | 35 (22%) | 19 (39%) |

| Procedure for Food Impaction Removal | 24 (19%) | 20 (18%) | 26 (17%) | 5 (22%) |

p<0.05

p<0.01

When patients were stratified by aeroallergen sensitivity, 157 patients were sensitized to at least one aeroallergen and 23 patients had no aeroallergen sensitivities (Table 2). Patient characteristics did not differ between groups, except aeroallergen sensitive patients were more likely to report concomitant asthma (p=0.017) and allergic rhinitis (p<001) compared to non-aeroallergen sensitive patients.

The distribution of peripheral eosinophil counts was comparable regardless of food or aeroallergen sensitivity (Table 3). The endoscopy findings of esophageal rings and linear furrows were commonly observed in all patient groups, 51–61% and 28–35%, respectively. Strictures were noted more often in aeroallergen sensitive (p=0.021) patients. In contrast, esophageal felinization was observed more often in non-aeroallergen sensitive patients (p=0.003).

Table 3.

Comparison of Patient Laboratory and Endoscopic Findings Stratified by Allergen Sensitivity

| Food Sensitive Patients | Aeroallergen Sensitive Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Yes (n=128) | No (n=108) | Yes (n=157) | No (n=23) |

| Peripheral Eosinophil Count | ||||

| Eos >500 | 19 (15%) | 21 (19%) | 29 (18%) | 2 (9%) |

| Eos <500 | 78 (61%) | 50 (46%) | 84 (54%) | 11 (48%) |

| Unknown | 31 (24%) | 37 (34%) | 44 (28%) | 10 (43%) |

| Endoscopic findings: | ||||

| Gastritis/Duodenitis | 17 (13%) | 8 (7%) | 13 (8%) | 4 (17%) |

| Esophageal Inflammation | 14 (11%) | 7 (6%) | 10 (6%) | 2 (9%) |

| Plaques | 12 (9%) | 6 (6%) | 10 (6%) | 3 (13%) |

| Erosions/Ulcers | 10 (8%) | 10 (9%) | 8 (5%) | 3 (13%) |

| Erythema | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Hiatal hernia | 16 (12%) | 20 (18%) | 26 (17%) | 3 (13%) |

| Fibrosis/Thickening | 5 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 6 (4%) | 1 (4%) |

| Rings | 68 (53%) | 66 (61%) | 80 (51%) | 12 (52%) |

| Linear Furrows | 42 (33%) | 38 (35%) | 45 (29%) | 8 (35%) |

| Felinization | 7 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (13%)** |

| Schatzki Ring | 11 (9%) | 8 (7%) | 13 (8%) | 0 (0%) |

| Stricture | 59 (46%) | 37 (34%) | 71 (45%)* | 4 (17%) |

| None of the Above | 21 (16%) | 15 (14%) | 15 (10%) | 2 (9%) |

| Unknown | 15 (12%) | 11 (10%) | 22 (14%) | 2 (9%) |

p<0.05

p<0.01

As shown in Table 4, Allergist treatment recommendations consisted primarily of proton pump inhibitor and/or swallowed steroid. As expected, food avoidance was recommended significantly more often for food sensitive patients compared to non-food sensitive patients (77% vs 9% respectively, p<0.001). The majority of patients reported symptomatic improvement at a subsequent follow up visit, and this did not significantly differ between the groups of food sensitive and non-food sensitive patients. Additionally, the recommendation of food avoidance for those patients who were food sensitive did not lead to differences in patient reported outcomes (Figure E1).

Table 4.

Comparison of Patient Treatment Recommendations and Reported Outcomes Stratified by Allergen Sensitivity

| Food Sensitive Patients | Aeroallergen Sensitive Patients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | Yes (n=128) | No (n=108) | Yes (n=157) | No (n=23) |

| Allergy Recommended Treatment | ||||

| Swallowed Steroid | 87 (68%) | 85 (79%) | 118 (75%) | 19 (82%) |

| PPI | 93 (73%) | 73 (68%) | 107 (68%) | 16 (69%) |

| H2 Blocker | 12 (9%) | 8 (7%) | 17 (11%) | 4 (17%) |

| Prednisone/Entocort | 8 (6%) | 4 (4%) | 7 (4%) | 1 (4%) |

| Montelukast | 5 (4%) | 5 (5%) | 7 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| No Treatment | 1 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) |

| PPI and Swallowed Steroid | 66 (52%) | 57 (53%) | 81 (52%) | 14 (61%) |

| Combination of Medications | 73 (57%) | 63 (58%) | 92 (59%) | 15 (69%) |

| Food Avoidance | 98 (77%)** | 10 (9%) | 76 (48%) | 6 (65%) |

| Patient Reported Outcomes | ||||

| No Change | 10 (8%) | 11 (10%) | 16 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

| Partial Improvement | 18 (14%) | 11 (10%) | 27 (17%) | 3 (13%) |

| Complete Improvement | 66 (52%) | 46 (43%) | 75 (48%) | 10 (43%) |

| Worse | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (4%) |

| Unknown | 33 (26%) | 37 (34%) | 37 (24%) | 8 (35%) |

p<0.01

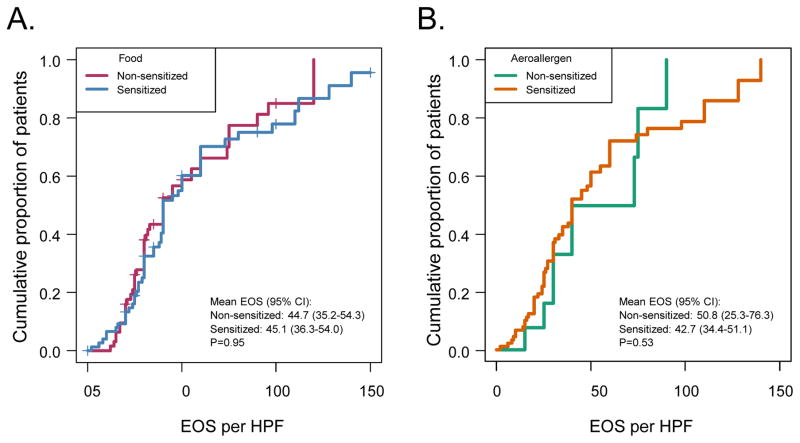

Esophageal biopsy eosinophils per high-powered-field (hpf) were analyzed with a parametric lognormal survival regression model. Eosinophil counts did not differ between food sensitive and non-food sensitive individuals (Figure 3A), or between aeroallergen sensitive and non-aeroallergen sensitive individuals (Figure 3B). It should be noted that were a few patients in each group that had biopsy eosinophils per hpf less than 15. These patients were still considered to have EoE per their gastroenterologist, due to other classical endoscopy findings consistent with the disease (rings, linear furrows).

Figure 3.

Eosinophil levels on esophageal biopsy. The eosinophil (EOS) count per high power field (HPF) is represented as a cumulative proportion of patients (on y-axis) that have less EOS count per HPF listed (on x-axis). A) The food allergen sensitive (Blue) and non-food allergen sensitive (Red) patients were compared. B) The aeroallergen sensitive (Orange) and non-aeroallergen sensitive (Green) patients were compared.

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with previously published reports that suggest that identification of IgE-mediated food sensitivities do not necessarily predict EoE trigger foods [11, 12]. We sought to further address whether there was another benefit to performing IgE based testing in adult EoE patients, specifically identifying a different clinical phenotype of adult EoE. To this end, we examined clinical and pathophysiological features of EoE to determine whether patients with food or aeroallergen sensitivity exhibited differences compared to patients without sensitivity.

There are several limitations to our study. A notable limitation to this study is the retrospective design without a standardized evaluation of EoE patients. There are now validated instruments for endoscopic and symptom scoring that would be essential for future prospective evaluations of EoE [14, 15]. Due to the retrospective nature of this study, we were unable to determine if patients were treated with a PPI prior to their endoscopic diagnosis. We recognize that this is a significant limitation, as this is now part of the diagnostic criteria for EoE. Likewise, our chart review was unable to establish why some patients did not have IgE mediated food and/or aeroallergen testing done. This is likely due to the fact that there is no standardized allergy evaluation in adult EoE, and the decision to perform allergy testing is based on provider discretion. An additional limitation is that our study only reflects the characteristics of patients with EoE seen in an allergy clinic. It is our experience that the decision to refer a patient with EoE to an Allergist is provider specific. However, it should be noted that our results reflect a subgroup of adult EoE patients and therefore might not apply to all adult EoE patients. It is possible that a more distinct phenotype of the disease would have been apparent had all the EoE patients been studied.

Our data show that identification of IgE-mediated food sensitivity does reveal a patient population that is in general more atopic, but otherwise does not distinguish a distinct clinical phenotypic of adult EoE. There were no significant clinical differences in patient demographics, patient reported symptoms, duration of symptoms, severity of disease, endoscopic findings, esophageal pathology, treatment or patient reported outcomes when comparing food sensitive versus non-food sensitive patients. We acknowledge that patient outcomes were subjective and did not include validated tools to assess follow up endoscopy, histologic examination, or patient related outcome measures [14–16].

Similarly, the identification of IgE-mediated aeroallergen sensitivity showed no significant clinical differences in patient demographics, patient reported symptoms, duration of symptoms, severity of disease, esophageal pathology, treatment or patient reported outcomes. A significant finding was that the endoscopy in aeroallergen sensitive patients more often revealed strictures. It is intriguing to consider whether this suggests differences in fibrotic versus inflammatory processes in the esophageal tissue. it is also notable that felinization was found less often in patients with aeroallergen sensitization, but this finding was relatively rare overall.

The role of targeted elimination diets based on allergy skin testing is unclear. Earlier studies showed success rates in children of 53% and 65% by using allergen patch testing and skin testing, respectively, to identify culprit foods [4, 17]. Recent studies demonstrated sensitization to food allergens in 50–82% of adult EoE patients [18, 19]. The most commonly identified food allergens were peanut, soy, egg, milk and tree nuts [20] as well as wheat, tomato, carrots and onions [19]. While adults with EoE commonly have a high rate of food sensitization, this sensitization rarely connotes actual food allergy or correctly identifies a causative agent for EoE [5]. In a study by Straumann et al., 29% of adult patients had sensitization to milk, egg, fish or seafood, but this was clinically relevant in only one patient [2]. Molina-Infante et al. treated 15 adult EoE patients with a targeted elimination diet and only 5 out of 15 had complete or partial histologic resolution of their EoE [11]. Gonsalves et al. found that retrospectively, skin prick testing would have only predicted 13% of trigger foods in adult EoE patients undergoing empiric elimination diets [12]. A recent systematic review of the various elimination diets reinforced the growing evidence that allergy-testing directed elimination diets are among the least successful elimination diets in adults, with an overall effectiveness of 32% [13]. Our study also failed to identify any clinical phenotypic difference associated with IgE-mediated food sensitivity.

EoE is considered an atopic disease and is commonly associated with other allergic diseases such as allergic rhinitis, asthma and atopic dermatitis [21, 22]. The pathogenesis of EoE is similar to that of other atopic conditions, primarily involving Th2 inflammation resulting in esophageal tissue expression of mediators such eotaxin-3, IL-13, and IL-5 [23–25]. Experimentally, EoE can also be induced in a mouse model by intrinsic Th2 cytokines such as IL-13 and IL-5 [26, 27]. Studies have demonstrated seasonal peaks of EoE symptoms and diagnosis, correlating with pollen seasons, suggesting a potential role of aeroallergens in the pathogenesis of EoE [28–30]. Prior studies have demonstrated aeroallergen sensitization in 86–93% of adult EoE patients [18, 19]. Experimentally, EoE has been induced by intranasal exposure to aeroallergens in mice [31]. Additionally, experimental epicutaneous allergen sensitization may potentially prime the body for respiratory allergen-induced EoE [32]. In a study with 63% of adult EoE patients exhibiting IgE mediated food sensitization, a majority of the patients were sensitized to foods that cross react with the pollens [21]. Most notably, these adult patients were sensitized to wheat and rye, which is cross-reactive with grass pollen. However, an elimination diet of wheat and rye failed to improve EoE symptoms in sensitized patients [33].

Our data confirm that there is no utility in identifying food IgE-mediated sensitivity for EoE in adult patients. The most notable finding from this study regarding potential phenotypes of EoE was the differing prevalence of strictures and felinization noted on endoscopy in aeroallergen versus non-aeroallergen sensitive subjects. This observation coupled with the findings of aeroallergen involvement in EoE in humans and mouse models suggest that evaluation for aeroallergen sensitivity could be important as a phenotypic distinction in EoE. Future prospective studies are needed to determine whether aeroallergen sensitivity truly defines a distinct phenotype of EoE, whether there are differences in the pathophysiology of EoE, and whether there is clinical relevance to the identification of aeroallergen sensitive EoE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH P01 HL088594

NIH R21 AI122103

NIH T32 GM008692

ABBREVIATIONS

- ED

Emergency Department

- EoE

Eosinophilic Esophagitis

- EOS

Eosinophil

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases-9th revision

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- SPT

Skin Prick Testing

- GERD

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease

- Hpf

High Powered Field

- PPI

Proton Pump Inhibitor

Footnotes

Trial Registration: Not Applicable

SKM reports holding office of President for the Wisconsin Allergy Society and is Principal Investigator for NIH funding. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015;35:145–59. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straumann A, Aceves SS, Blanchard C, et al. Pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: similarities and differences. Allergy. 2012;67:477–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1503–12. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90637-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spergel JM, Brown-Whitehorn TF, Cianferoni A, et al. Identification of causative foods in children with eosinophilic esophagitis treated with an elimination diet. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:461–7. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aceves SS. Food allergy testing in eosinophilic esophagitis: what the gastroenterologist needs to know. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2014;12:1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowitz JE, Spergel JM, Ruchelli E, Liacouras CA. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2003;98:777–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07390.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2013;108:759–66. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Gomez Torrijos E, Lopez Viedma B, et al. Efficacy of IgE-targeted vs empiric six-food elimination diets for adult eosinophilic oesophagitis. Allergy. 2014;69:936–42. doi: 10.1111/all.12420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Barrio J, Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Sanchez-Cazalilla M, Lucendo AJ. Four-food group elimination diet for adult eosinophilic esophagitis: A prospective multicenter study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1093–9. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagalwalla AF, Sentongo TA, Ritz S, et al. Effect of six-food elimination diet on clinical and histologic outcomes in eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2006;4:1097–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molina-Infante J, Martin-Noguerol E, Alvarado-Arenas M, Porcel-Carreno SL, Jimenez-Timon S, Hernandez-Arbeiza FJ. Selective elimination diet based on skin testing has suboptimal efficacy for adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1200–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1451–9. e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.001. quiz e14-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:1639–48. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoepfer AM, Straumann A, Panczak R, et al. Development and Validation of a Symptom-Based Activity Index for Adults with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1255–1266. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–95. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azzawi M, Bradley B, Jeffery PK, et al. Identification of activated T lymphocytes and eosinophils in bronchial biopsies in stable atopic asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;142:1407–1413. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/142.6_Pt_1.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1570–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy-Ghanta S, Larosa DF, Katzka DA. Atopic characteristics of adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2008;6:531–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penfield JD, Lang DM, Goldblum JR, Lopez R, Falk GW. The role of allergy evaluation in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2010;44:22–7. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a1bee5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dominguez-Ortega J, Perez-Bedmar J, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, Butron M, Kindelan C, Ledesma A. Eosinophilic esophagitis due to profilin allergy. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2009;19:338–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon D, Marti H, Heer P, Simon HU, Braathen LR, Straumann A. Eosinophilic esophagitis is frequently associated with IgE-mediated allergic airway diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1090–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon D, Straumann A, Simon HU. Eosinophilic esophagitis and allergy. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland) 2014;32:30–3. doi: 10.1159/000357006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: Transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2007;120:1292–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wechsler JB, Bryce PJ. Allergic mechanisms in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2014;43:281–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:954–61. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra A, Rothenberg ME. Intratracheal IL-13 induces eosinophilic esophagitis by an IL-5, eotaxin-1, and STAT6-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1419–27. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. IL-5 promotes eosinophil trafficking to the esophagus. J Immunol. 2002;168:2464–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almansa C, Krishna M, Buchner AM, et al. Seasonal distribution in newly diagnosed cases of eosinophilic esophagitis in adults. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2009;104:828–33. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogg MI, Ruchelli E, Spergel JM. Pollen and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;112:796–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(03)01715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moawad FJ, Veerappan GR, Lake JM, et al. Correlation between eosinophilic oesophagitis and aeroallergens. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2010;31:509–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04199.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mishra A, Hogan SP, Brandt EB, Rothenberg ME. An etiological role for aeroallergens and eosinophils in experimental esophagitis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;107:83–90. doi: 10.1172/JCI10224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akei HS, Mishra A, Blanchard C, Rothenberg ME. Epicutaneous antigen exposure primes for experimental eosinophilic esophagitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:985–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon D, Straumann A, Wenk A, Spichtin H, Simon HU, Braathen LR. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults--no clinical relevance of wheat and rye sensitizations. Allergy. 2006;61:1480–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.