Abstract

Purpose

The Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA) has conducted nationwide surveys every 5 years, targeting patients who received surgical treatment for gastric cancer. We report the results of the 2014 nationwide survey and compare them to those of the 1995, 1999, 2004, and 2009 surveys.

Materials and Methods

From March 2015 to January 2016, a standardized case report form was sent to every member of the KGCA via e-mail. The survey consisted of 29 questions, regarding patient demographics as well as tumor-, and surgery-related factors. The completed data forms were analyzed by the KGCA information committee.

Results

Data on 15,613 patients were collected from 69 institutions. The mean age was 60.9±12.1 years, and the proportion of patients more than 70 years of age increased from 9.1% in 1995 to 25.3% in 2014. Proximal cancer incidence steadily increased from 11.2% in 1995 to 16.0% in 2014. Early gastric cancer incidence consistently increased and accounted for 61.0% of all cases in 2014. The surgical approach was diversified in 2014, and 7,818 cases (50.1%) were treated with a minimally invasive approach. The most common anastomosis was Billroth I (50.2%) after distal gastrectomy, and the proportion of Roux-en-Y anastomoses performed increased to 8.6%.

Conclusions

The results of this survey are expected to be important data for future studies and to be useful for generating a national cancer control program.

Keywords: Stomach neoplasms, Health care surveys, Korea

Introduction

In South Korea, gastric cancer is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in men and the fourth most common cancer in women.1,2 Approximately 30,000 new gastric cancer cases were reported in 2013, which accounted for approximately 13.4% of all cancer cases diagnosed. The Korean Central Cancer Registry reports nationwide cancer statistics annually, including the incidence, survival rates, and prevalence; however, the reports do not include the detailed clinicopathological characteristics of gastric cancer or treatment-related information.

In 1999, the Korean Gastric Cancer Association (KGCA) started a nationwide survey that targeted patients who received surgical treatment for gastric cancer. The first report included 5,380 patients surgically treated at 28 hospitals in 1995 as well as 6,772 patients treated at 29 hospitals in 1999.3 The clinicopathological factors were compared between these two periods (1995 vs. 1999) and were analyzed by regional groups according to hospital locations. In the second survey, a total of 11,293 patients who had been surgically treated at 57 hospitals in 2004 were included. The clinicopathological factors and surgical methods were evaluated, and these factors were compared among the 1995, 1999, and 2004 surveys.4 The third survey included 14,658 patients surgically treated at 59 hospitals in 2009, and the surgical approaches were newly evaluated according to the expansion of minimally invasive surgery.

Here, we present the results of the 2014 nationwide survey. The clinicopathological and surgery-related factors were compared with those of the previous surveys.

Materials and Methods

1. Data collection

This nationwide survey was conducted among the members of the KGCA from March 2015 to January 2016 and targeted patients who had been treated surgically for gastric cancer in 2014. A standardized electronic case report form (Microsoft Excel®; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) was sent to every member of the KGCA via e-mail, and one member from each institution was asked to complete the case report form. After the first invitation to participate, several reminders were sent to all KGCA members, and direct contact via a phone call was performed for some nonrespondents.

This study followed the ethical principles for medical research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2. Survey data

The survey data consisted of 29 questions regarding patient demographic factors (age, sex, height, weight, and American Society of Anesthesiologists score) as well as tumor factors (number of lesions, tumor size, tumor location, macroscopic type, histologic type, Lauren's classification, lymphatic invasion, depth of tumor invasion, lymph node metastasis, presence of distant metastasis, and numbers of metastatic and harvested lymph nodes) and surgery-related factors (surgical approach, resection extent, combined resection, reconstruction method, stapler used, curability, blood loss, and operation time) (Appendix 1).

Tumor location and macroscopic findings were classified according to Japanese guidelines.5 Tumor locations were described as lower, middle, upper third, or whole stomach, and the most involved portion was reported as the tumor location when a large tumor occupied two stomach locations. Macroscopic gross types were described as types I, IIa, IIb, IIc, or III for early gastric cancers and as B1, B2, B3, or B4 for advanced gastric cancers. Histological types were classified according to the 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) classification.6 When a tumor consisted of components of two histological types, the quantitative predominance was recorded as the macroscopic type. The depth of invasion, lymph node metastasis, and distant metastases were categorized according to the 7th American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system.7

Surgical approaches were subdivided as open, laparoscopy, robot, and others. Laparoscopy included laparoscopy-assisted, totally laparoscopic, reduced-port, and single-port surgery. Anastomosis methods were separately evaluated according to the surgery type.

For clinicopathological factors, the results of the 1995, 1999, 2004, and 2009 nationwide surveys were used to evaluate changes.3,4,8 Surgery-related factors have been collected since 2004, and the results of the 2004 and 2009 surveys were used for comparisons of these factors.

3. Statistical analysis

The KGCA information committee analyzed the completed data forms retrieved from each institution. Incorrectly entered data were converted to correctly coded data. Missing values were either treated as 'unknowns' in the analysis of categorical data or were excluded from the analysis of continuous data.

Continuous values were presented as means±standard deviations, while categorical variables were shown as proportions. Statistical differences were tested using t-test and chi-square tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and P<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

1. Participating institutions and patients

A total of 69 institutions participated in the survey, and data on 15,613 patients who underwent a surgery for gastric cancer in 2014 were collected. Of the 69 institutions, 26 performed fewer than 100 surgeries, 20 performed 100~199 surgeries, and 16 performed 200~499 surgeries. Seven institutions performed more than 500 surgeries and 46% (7,184/15,613) of all surgeries were performed at these seven institutions.

2. Patient age and sex distribution

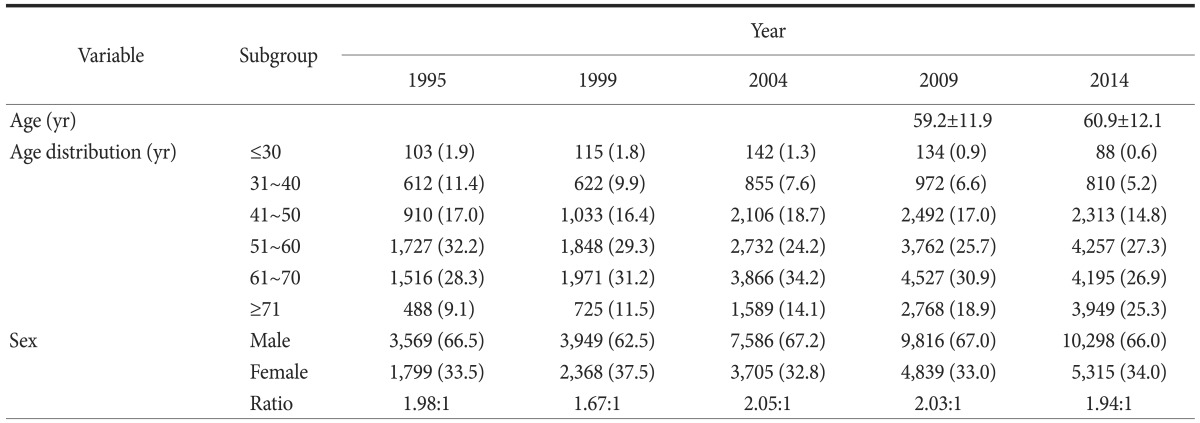

The mean patient age was 60.9±12.1 years, and the distribution according to age groups is shown in Table 1. Compared with previous surveys, the proportion of young patients (less than 40 years of age) decreased from 13.3% in 1995 to 5.8% in 2014, and the number of elderly patients (more than 70 years of age) increased continuously, from 9.1% in 1995 to 25.3% in 2014

Table 1. Age and sex distribution according to study period.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or number (%). The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding.

The male to female ratio was approximately 2:1, with no notable change over the 20 years during which the surveys have been conducted.

3. Histopathological characteristics

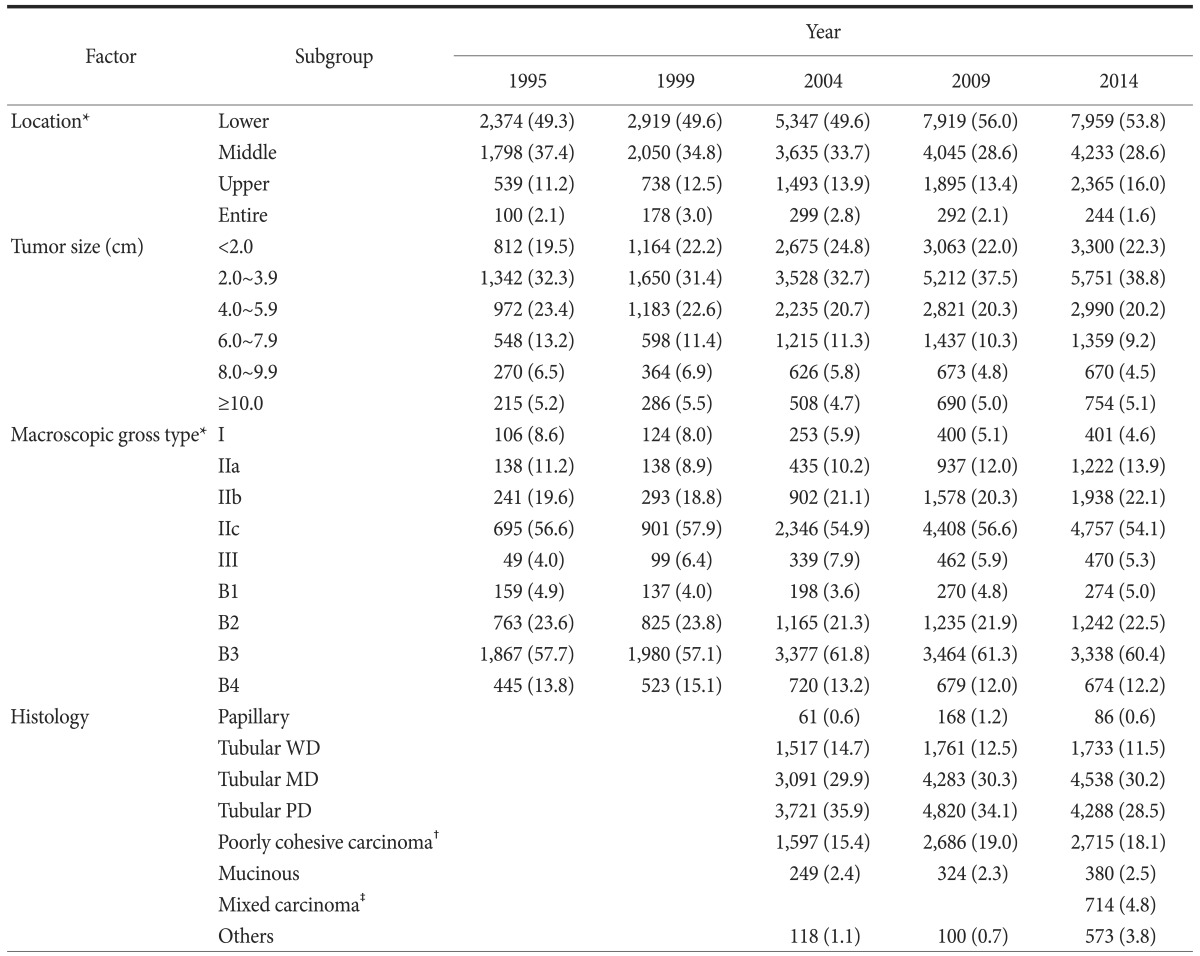

Table 2 shows the histopathological characteristics of the gastric cancers. The most common site was the lower one-third of the stomach, which accounted for 53.8% of all such cases. The proportion of cases with cancer in the upper one-third of the stomach steadily increased from 11.2% in 1995 to 16.0% in 2014. The most common tumor size was 2.0~3.9 cm (38.8%), followed by less than 2.0 cm (22.3%) and 4.0~5.9 cm (20.2%). The distribution of tumor size did not significantly change over time. For the macroscopic gross type, the proportion of type I decreased slightly, while that of type IIa and IIb has increased since 1999. Type IIc was the most prevalent gross type among early gastric cancer types (54.1%), and Borrmann type 3 was the most prevalent of advanced gastric cancer types (60.4%). Histology has been evaluated since 2004, and the 2000 WHO classification was used in the 2004 and 2009 surveys9; however, the WHO classification was revised in 2010, and a new category, mixed carcinoma, was included in the histological classification in the 2014 survey.6 Moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma was the most common histological type, followed by poorly differentiated, signet ring cell, and well-differentiated types.

Table 2. Histopathological characteristics of gastric cancer according to study period.

Values are presented as number (%). The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding. WD = well differentiated; MD = moderately differentiated; PD = poorly differentiated. *Classification according to the Japanese guidelines.5 †Includes signet-ring cell carcinoma. ‡Display a mixture of discrete morphologically identifiable glandular (tubular/papillary) and signet-ring/poorly-cohesive cellular histological components.

4. Tumor stage

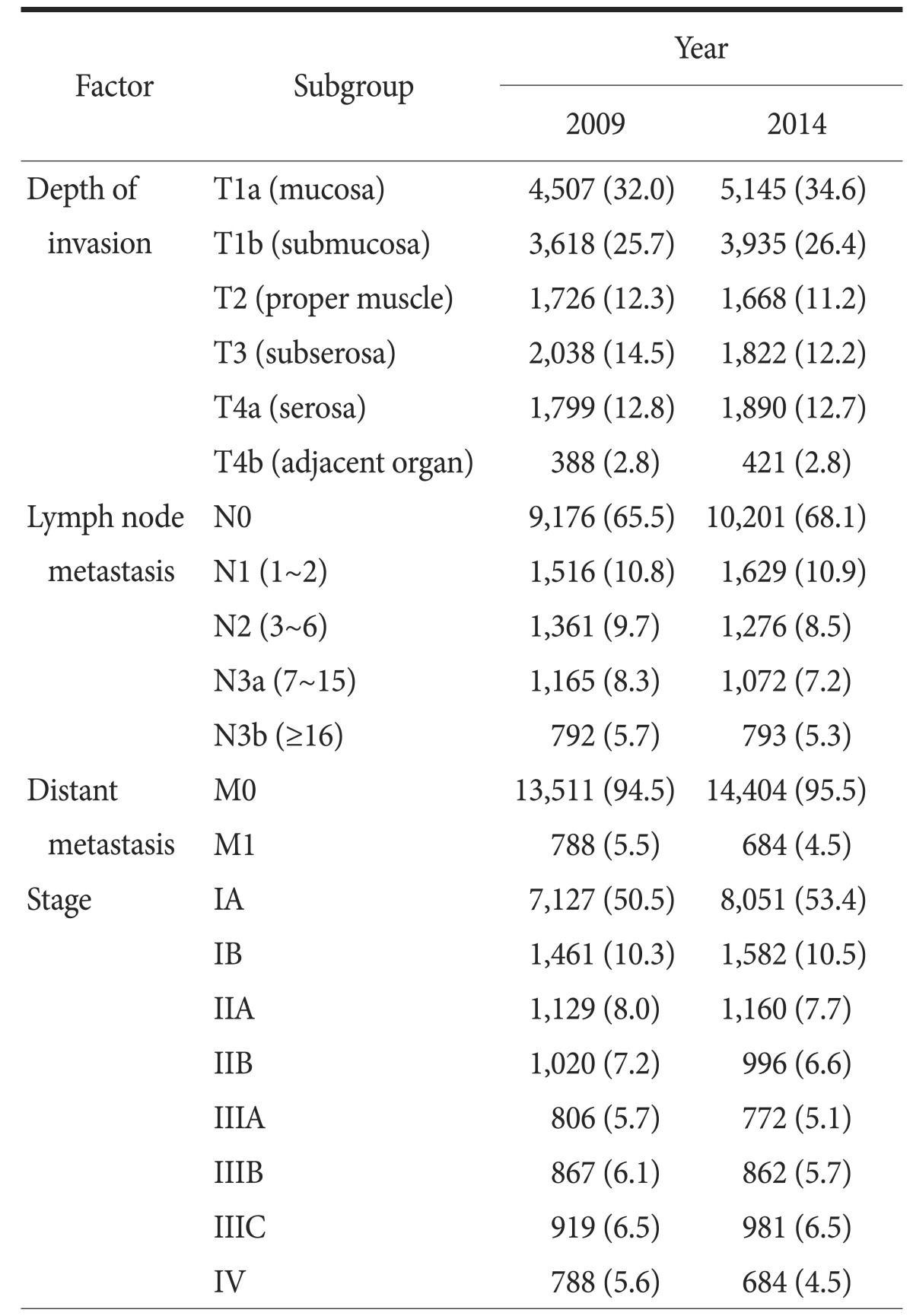

TNM classification was revised the 2010, 7th edition; however, raw data from the 1995, 1999, and 2004 surveys were inaccessible. Therefore, the overall tumor stages are shown for only the 2009 and 2014 survey data (Table 3). The proportion of T1 cancers has consistently increased (30.4% in 1995, 35.4% in 1999, 47.4% in 2004, and 57.7% in 2009) to 61.0% in 2014. The proportion of node-negative cancers also has constantly increased (50.4% in 1995, 55.3% in 1999, 57.9% in 2004, and 65.6% in 2009), reaching 68.1% in 2014. The number of stage IA tumors has increased over time, while the number of other tumor stages has remained the same or decreased.

Table 3. TNM stages according to AJCC classification, seventh edition.

Values are presented as number (%). The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding. AJCC = American Joint Committee on Cancer.

5. Surgery-related factors

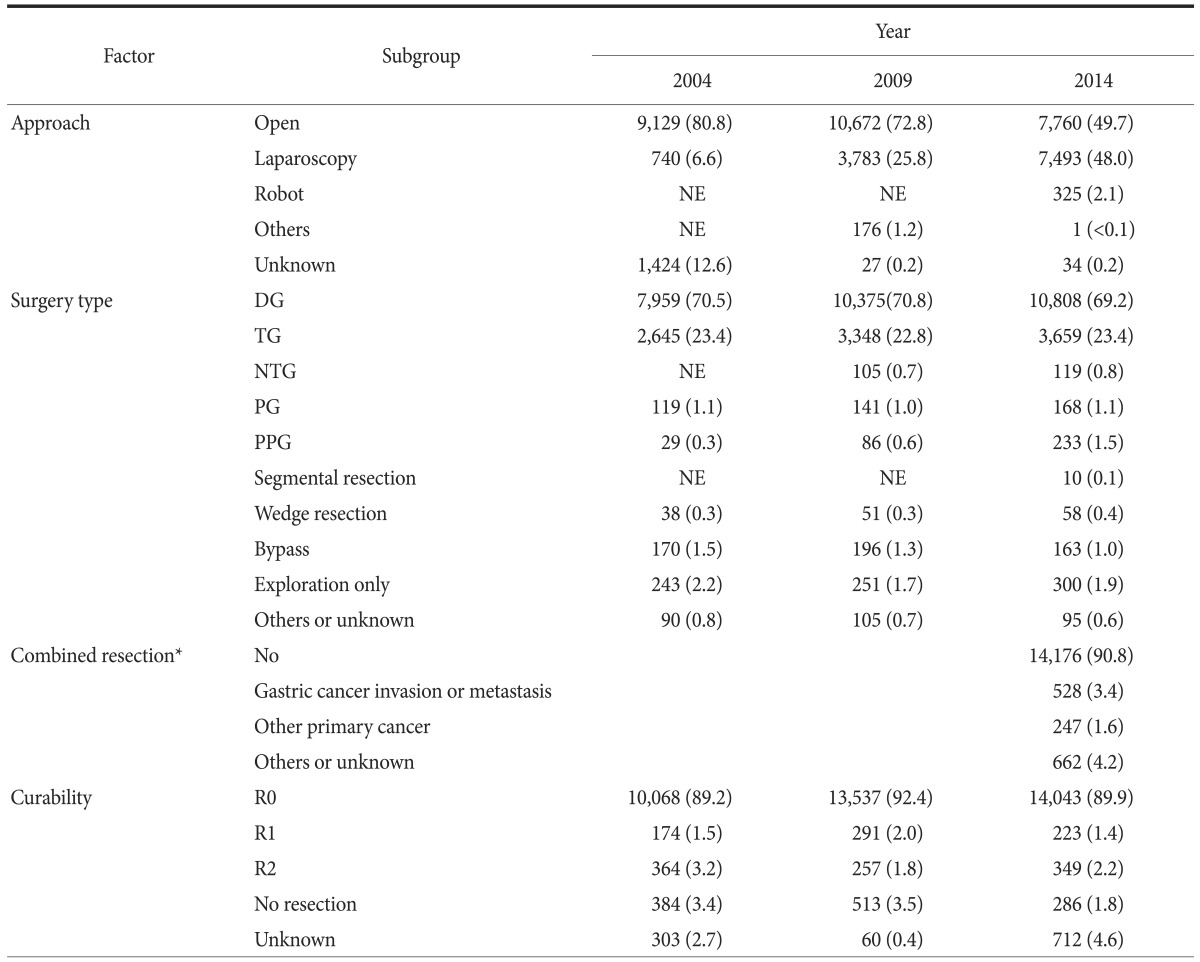

Surgery-related factors were evaluated from 2004 and are summarized in Table 4 and 5. The proportion of open surgery decreased from 80.8% in 2004 to 49.7% in 2014; however, the use of laparoscopic approaches increased from 6.6% to 48.0%. A total of 7,493 laparoscopic surgeries were performed in 2014, including 2,805 laparoscopy-assisted (18.0%), 4,388 totally laparoscopic (28.1%), 198 reduced-port (1.3%), and 102 single-port (0.7%) surgeries. Robotic surgery was performed in 325 patients (2.1%).

Table 4. Operative methods and curability.

Values are presented as number (%). The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding. NE = not evaluated (the item was not included as a choice); DG = distal gastrectomy; TG = total gastrectomy; NTG = near total gastrectomy; PG = proximal gastrectomy; PPG = pylorus preserving gastrectomy. *Combined resection was initially evaluated in the 2014 survey.

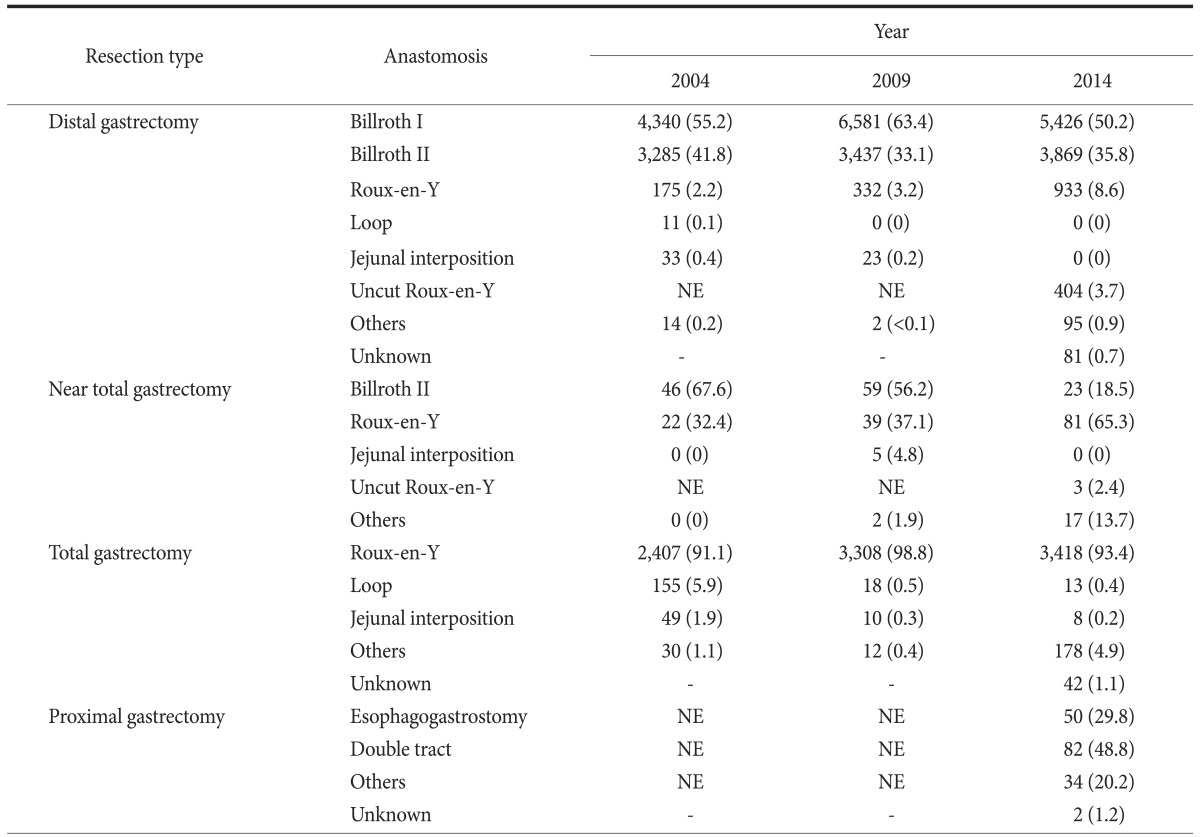

Table 5. Methods of anastomosis according to resection types.

Values are presented as number (%). The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding. NE = not evaluated (the item was not included as a choice).

Few changes in the surgery type and curability were observed during the study period. Subtotal and total gastrectomies were performed in 10,808 patients (69.2%) and 3,659 patients (23.4%), respectively. The number of pylorus-preserving gastrectomies increased from 29 cases (0.3%) in 2004 to 233 cases (1.5%) in 2014, and wedge resection (58 cases, 0.4%) was mainly performed based on a clinical trial. The proportion of R0 resections was lower in 2014 (89.9%). However, there are a number of missing values referring to curability in 2014 (712 cases); if the missing values were excluded, the proportion of R0 resections was 94.2% (14,043/14,901). Combined resection for gastric cancer invasion or metastasis was performed in 528 patients (3.4%) in 2014.

Table 5 shows the reconstruction methods according to surgery type. The most common reconstruction method after distal gastrectomy was Billroth I (50.2%), followed by Billroth II (35.8%), Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (8.6%), and uncut Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy (3.7%). After near-total gastrectomy, the proportion of Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomies performed was 65.3%, which increased compared with previous study periods. After total gastrectomy, Roux-en-Y esophagojejunostomy was typically performed (93.4%). Anastomosis after proximal gastrectomy was initially evaluated during this time, and the double-tract method (48.8%) was used more commonly than esophagogastrostomy (29.8%).

6. Newly evaluated surgery-related details in 2014

In 2014, detailed surgical approaches were evaluated, particularly minimally invasive approaches. Therefore, reconstruction methods after distal gastrectomy according to surgical approaches were analyzed (Table 6). Billroth I anastomosis was performed in approximately 60% of open or laparoscopy-assisted surgeries. However, Billroth II was the most common reconstruction method in totally laparoscopic or reduced-port surgeries. The proportion of Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomies was higher in totally laparoscopic or reduced-port surgeries compared with the proportions in open or laparoscopy-assisted surgeries.

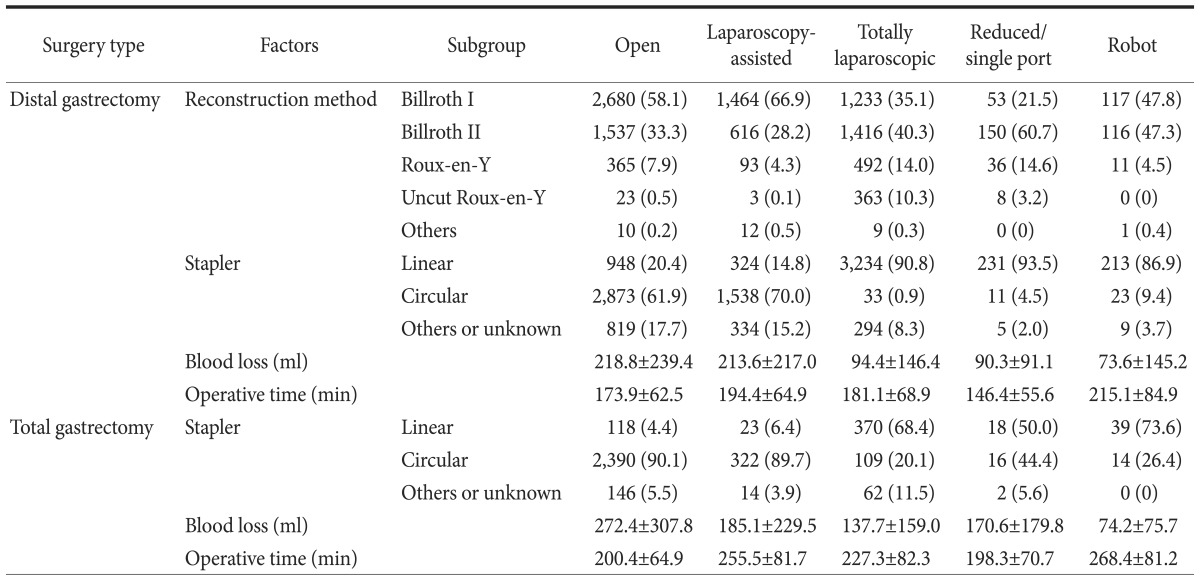

Table 6. Reconstruction methods, type of stapler, blood loss, and operative time according to surgical approaches in 2014.

Values are presented as number (%) or mean±standard deviation. The sum of the percentages does not equal 100% because of rounding.

The type of stapler, patient blood loss, and operative times were also evaluated in the 2014 survey. After distal gastrectomy, circular staplers were commonly used in open or laparoscopy-assisted approaches (61.9% and 70.0%, respectively). However, linear staplers were mostly used in totally laparoscopic or reduced-port approaches (90.8% and 93.5%, respectively). The volume of blood loss was smaller in totally laparoscopic or reduced-port surgeries, and smallest in robotic surgeries compared with those in open or laparoscopy-assisted surgeries. Robotic surgery had the longest operative times. Similar patterns were observed in total gastrectomy cases.

Discussion

This survey evaluated changes in the clinicopathological and surgery-related factors from 1995 to 2014. We observed that the number of elderly patients with gastric cancer is increasing and that proximal gastric cancer increased slightly from 11.2% to 16.0% of cases. The proportion of early gastric cancer increased, accounting for 61% of cancer cases in 2014. Treatment with minimally invasive approaches expanded to 50.1% of all cases, and several changes in anastomosis method after gastrectomy were observed.

The increasing lifespan of Koreans has subsequently led to an increase in the number of elderly patients. The proportion of patients over 70 years of age increased from 9.1% in 1995 to 25.3% in 2014, and 497 cases were patients over 80 years of age. This trend of increasing elderly patients will influence the clinical field because a comprehensive preoperative evaluation, meticulous surgery, and careful postoperative management are required for this population. Currently, many elderly patients are healthy and the operative risk is negligible; however, some have many risk factors, and patients and their caregivers should be aware of surgery risks. Therefore, surgeons should increase their knowledge of elderly patients in order to manage them properly.

One timely question is whether the number of proximal cancer cases is increasing in Korea. As the Korean diet has become Westernized and people are gaining more weight, the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux has increased.10 In the literature, cardia cancer was positively associated with Westernized dietary patterns, obesity, and gastroesophageal reflux symptoms.11,12,13,14,15 Therefore, the incidence of proximal gastric cancer was expected to increase. In our data, while the lower one-third of the stomach remains the most common tumor location, the proportion of instances of proximal cancer is steadily increasing.

The increase in early gastric cancer is an ongoing trend. Concurrently, tumors meeting an indication of endoscopic resection have also increased, and the role of endoscopic treatment is gradually increasing; however, a debate remains in terms of the indications for endoscopic treatment. More studies are necessary to prove the oncological safety and outcomes of endoscopic treatment. In particular, a multidisciplinary approach would be useful for selecting between endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgery when determining a treatment plan for elderly people or high-risk patients.

An increased incidence of early gastric cancer may also lead to improvement in the long-term survival of patients with gastric cancer. According to an annual report of cancer statistics published in 2013, the 10-year survival rate increased from 39.9% in patients whose cancer was diagnosed in 1993~1995 to 60.7% in 2004~2008.1 As the number of gastric cancer survivors continues to rise, postgastrectomy symptoms and quality of life become increasingly important issues. The expansion of minimally invasive surgical approaches and function-preserving surgery are also associated with these improved long-term outcomes.

Currently, the concepts of minimally invasive surgery have developed in two directions: surgical approach and surgical extent. For surgical approach, the proportion of cases that underwent minimally invasive approaches has increased. Various types were observed in 2014, including reduced-port, single-port, and robotic surgery. In 2009, the primary minimally invasive approach was laparoscopy-assisted surgery, but the totally laparoscopic approach ranked first in 2014. For the aspect of surgical extent, the proportion of function-preserving gastrectomies has increased. Pylorus-preserving gastrectomies have steadily increased, and 58 patients underwent wedge resection based on a clinical trial of sentinel lymph node navigation surgery in 2014.16

As minimally invasive approaches advanced from extracorporeal to intracorporeal anastomosis, several changes were observed. In terms of reconstruction methods, Billroth I anastomosis using a circular stapler was commonly used in open or laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomies. However, in totally laparoscopic or reduced port distal gastrectomy, Billroth II anastomosis using linear staplers was the most common method. Similar patterns were observed in total gastrectomies, and linear staplers were more commonly used for totally laparoscopic and reduced-port approaches.

The increase in Roux-en-Y anastomosis after distal gastrectomy can be interpreted as an effort to improve postoperative symptoms and patient quality of life. In recent studies, Roux-en-Y anastomosis yielded better outcomes in postoperative endoscopic findings, including food residue, gastritis, and bile reflux, compared with other reconstruction methods.17,18,19 Additionally, visceral fat loss was greater for Roux-en-Y anastomosis, which could help reduce metabolic syndrome.20,21 Although this surgery takes more time to perform, it is expected to become more commonly performed based on its clear advantages; however, debate remains, and further studies are required.22

In conclusion, this nationwide survey revealed several gastric cancer changes and trends in Korea. Moreover, this survey provides important evidence for creating national policy and a program for cancer control.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Korean Academy of Medical Sciences.

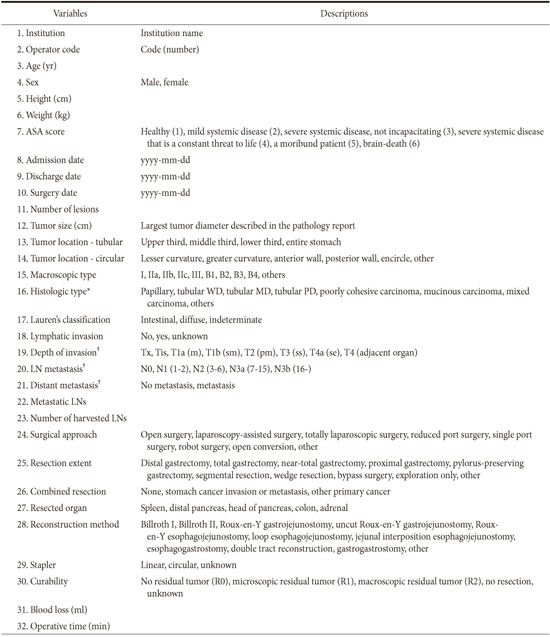

Appendix 1

Survey data

ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; WD = well differentiated; MD = moderately differentiated; PD = poorly differentiated; LN = lymph node. *World Health Organization classification of tumors of the stomach, 2010; †Based on the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification of gastric carcinoma.

Footnotes

The Information Committee: Bang Wool Eom (National Cancer Center), Hye Seong Ahn (SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center), In Seob Lee (University of Ulsan College of Medicine), Jae-Seok Min (Dongnam Institute of Radiological & Medical Sciences), Young Gil Son (Keimyung Univerisity School of Medicine), Sang Eok Lee (College of Medicine, Konyang University), Ji Hoon Kim (Gangneung Asan Hospital), Se-Youl Lee (Chonbuk National University Medical School), Jie-Hyun Kim (Yonsei University College of Medicine), Sang-Hoon Ahn (Seoul National University College of Medicine), Hyung-Ho Kim (Seoul National University College of Medicine), Young-Woo Kim (National Cancer Center)

Participating Institutions: The participating institutions are as follows: The Catholic University of Korea, Bucheon St. Mary's Hospital; The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary's Hospital; The Catholic University of Korea, St. Vincent's Hospital; The Catholic University of Korea, Yeouido St. Mary's Hospital; The Catholic University of Korea, Uijeongbu St. Mary's Hospital; The Catholic University of Korea, Incheon St. Mary's Hospital; Gachon University Gil Medical Center; Gangneung Asan Hospital; Konkuk University Medical Center; Konyang University Hospital; Kyungpook National University Hospital; Kyungpook National University Medical Center; Gyeongsang National University Hospital; Kyunghee University Medical Center; Keimyung University Dongsan Medical Center; Korea University Guro Hospital; Korea University Ansan Hospital; Korea University Anam Hospital; Kosin University Gospel Hospital; National Police Hospital; National Cancer Center; National Medical Center; Daegu Catholic University Medical Center; Eulji University Hospital; Dongnam Institution of Radiological & Medical Sciences; Dong-A University Hospital; Myongji Hospital; Pusan National University Hospital; Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital; Bundang Jesaeng Hospital; CHA Bundang Medical Center, CHA University; Samsung Medical Center; Seoul National University Hospital; SMG-SNU Boramae Medical Center; Seoul National University Bundang Hospital; Asan Medical Center; Saegyaero Hospital; Soon Chun Hyang University Bucheon Hospital; Soon Chun Hyang University Seoul Hospital; Soon Chun Hyang University Cheonan Hospital; Ajou University Medical Center; Hansarang Hospital; Gangnam Severance Hospital; Severance Hospital; Wonju Severance Christian Hospital; Yeungnam University Medical Center; Presbyterian Medical Center; Ulsan University Hospital; Wonkang University Hospital; Korea Cancer Center Hospital; Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital; Inje University Busan Paik Hospital; Inje University Haeundae Paik Hospital; Inha University Hospital; Seoul Red Cross Hospital; Chonnam National University Hospital; Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital; Chonbuk National University Hospital; Jeju National University Hospital; Chosun University Hospital; Chung-Ang University Hospital; Chinjujeil Hospital; Cheongju St. Mary's Hospital; Chungnam National University Hospital; Chungbuk National University Hospital; Gyeonggi-do Medical Center Paju Hospital; Hallym University Dongtan Sacred Heart Hostpial; Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital; Hanyang University Seoul Hospital.

Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.National Cancer Information Center [Internet] Goyang: National Cancer Center; 2015. [cited 2016 May 31]. Available from: http://www.cancer.go.kr/mbs/cancer/jsp/album/gallery.jsp?boardType=02&boardId=31817&listType=02&boardSeq=15022674&mcategoryId=&id=cancer_050207000000&spage=1#. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oh CM, Won YJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Cho H, Lee JK, et al. Cancer Statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2013. Cancer Res Treat. 2016;48:436–450. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korea Gastric Cancer Association. Nationwide Gastric Cancer Report in Korea Korea Gastric Cancer Association. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2002;2:105–114. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Information Committee of the Korean Gastric Cancer Association. 2004 Nationwide Gastric Cancer Report in Korea. J Korean Gastric Cancer Assoc. 2007;7:47–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101–112. doi: 10.1007/s10120-011-0041-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. Vol 3. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeong O, Park YK. Clinicopathological features and surgical treatment of gastric cancer in South Korea: the results of 2009 nationwide survey on surgically treated gastric cancer patients. J Gastric Cancer. 2011;11:69–77. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2000. pp. 37–68. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min BH, Huh KC, Jung HK, Yoon YH, Choi KD, Song KH, et al. Prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease in Korea: a population-based study using the Rome III criteria. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2721–2729. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3243-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh R, Watabe H, Yazdanbod A, Fyfe V, Kazemi A, et al. Combination of gastric atrophy, reflux symptoms and histological subtype indicates two distinct aetiologies of gastric cardia cancer. Gut. 2008;57:298–305. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lagergren J, Bergström R, Lindgren A, Nyrén O. Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux as a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:825–831. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903183401101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu AH, Tseng CC, Bernstein L. Hiatal hernia, reflux symptoms, body size, and risk of esophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 2003;98:940–948. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bertuccio P, Rosato V, Andreano A, Ferraroni M, Decarli A, Edefonti V, et al. Dietary patterns and gastric cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:1450–1458. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olefson S, Moss SF. Obesity and related risk factors in gastric cardia adenocarcinoma. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:23–32. doi: 10.1007/s10120-014-0425-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JY, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Nam BH, Lee YJ, Jeong SH, et al. Assessment of laparoscopic stomach preserving surgery with sentinel basin dissection versus standard gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy in early gastric cancer-A multicenter randomized phase III clinical trial (SENORITA trial) protocol. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:340. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2336-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim CH, Song KY, Park CH, Seo YJ, Park SM, Kim JJ. A comparison of outcomes of three reconstruction methods after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy. J Gastric Cancer. 2015;15:46–52. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2015.15.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park JY, Kim YJ. Uncut Roux-en-Y reconstruction after laparoscopic distal gastrectomy can be a favorable method in terms of gastritis, bile reflux, and gastric residue. J Gastric Cancer. 2014;14:229–237. doi: 10.5230/jgc.2014.14.4.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong JJ, Altaf K, Javed MA, Nunes QM, Huang W, Mai G, et al. Roux-en-Y versus Billroth I reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1124–1134. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanaka K, Takiguchi S, Miyashiro I, Hirao M, Yamamoto K, Imamura H, et al. Impact of reconstruction method on visceral fat change after distal gastrectomy: results from a randomized controlled trial comparing Billroth I reconstruction and rouxen-Y reconstruction. Surgery. 2014;155:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tanaka K, Miyashiro I, Yano M, Kishi K, Motoori M, Shingai T, et al. Visceral fat changes after distal gastrectomy according to type of reconstruction procedure for gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:146. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakamura M, Nakamori M, Ojima T, Iwahashi M, Horiuchi T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing long-term quality of life for Billroth I versus Roux-en-Y reconstruction after distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2016;103:337–347. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]