ABSTRACT

Insertion sequences (ISs) are widespread in the genome of Mycoplasma bovis strain PG45, but no ISs were identified within its two tandemly positioned rRNA operons (rrn1 and rrn2). However, characterization of the rrn locus in 70 M. bovis isolates revealed the presence of ISs related to the ISMbov1 (IS30 family) and ISMbov4 (IS4 family) isomers in 35 isolates. ISs were inserted into intergenic region 1 (IGR-1) or IGR-3, which are the putative promoter regions of rrn1 and rrn2, respectively, and into IGR-5, located downstream of the rrl2 gene. Seven different configurations (A to G) of the rrn locus with respect to ISs were identified, including those in five annotated genomes. The transcriptional start site for the single rrn operon in M. bovis strain 88127 was mapped within IGR-1, 60 bp upstream of the rrs gene. Notably, only 1 nucleotide separated the direct repeat (DR) for ISMbov1 and the promoter –35 element in configuration D, while in configuration F, the −35 motif was a part of the ISMbov1 DR. Relative quantitative real-time (qRT) PCR analysis and growth rate comparisons detected a significant increase (P < 0.05) in the expression of the rrs genes and in the number of viable cells during log phase growth (8, 12, and 16 h) in the strains with configuration F in comparison to strains with one or two rrn operons that did not have ISs. A high prevalence of IS elements within or close to the M. bovis rrn operon-promoter region may reflect their important role in regulation of both ribosome synthesis and function.

IMPORTANCE Data presented in this study show a high prevalence of diverse ISs within the M. bovis rrn locus resulting in intraspecies variability and diversity. Such abundance of IS elements near or within the rrn locus may offer a selective advantage to M. bovis. Moreover, the fact that expression of the rrs genes as well as the number of viable cells increased in the group of strains with IS element insertion within a putative promoter −35 sequence (configuration F) in comparison to that in strains with one or two rrn operons that do not have ISs may serve as a basis for understanding the possible role of M. bovis IS elements in fundamental biological processes such as regulation of ribosome synthesis and function.

INTRODUCTION

The bacterial 70S ribosome is composed of large (50S) and small (30S) subunits, each of which is a ribonucleoprotein complex. The ribosome contains three rRNA genes: genes encoding two large-subunit-associated rRNAs (23S and 5S) and the small-subunit rRNA (16S). The genes encoding rRNA usually form an operon designated rrn with a typical configuration of rrs-rrl-rrf (where rrs, rrl, and rrf are the genes encoding the 16S, 23S, and 5S rRNAs, respectively). Sometimes tRNA genes are found between rrs and rrl or downstream of rrf genes. However, other configurations of the rrn operon with respect to the classical one (rrs-rrl-rrf) are also seen (1). The rRNA genes are cotranscribed as a polycistronic precursor, which undergoes posttranscriptional modifications. Sometimes, transcription of rRNA genes may be carried out from more than one promoter, as has been shown for Escherichia coli, in which transcription of rRNA genes occurs from two tandem promoters, P1 and P2, separated by about 100 bp (2).

The number of rrn operons varies among bacterial species. For example Mycobacterium tuberculosis (44) and Rickettsia prowazekii (3) have one rrn operon, and Helicobacter pylori has two rrn operons (4), while E. coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Clostridium paradoxum contain 7, 10, and 15 rrn operons per genome, respectively (5–7). In the small, cell-wall-less Mycoplasma species, belonging to the class Mollicutes, the number of rrn operons usually varies from one to two, although some species (e.g., Mycoplasma canis and Mycoplasma cynos) have three rrn loci (deduced from accession no. CP011368.1 and HF559394.1).

A systematic analysis of the complete genome of the bovine pathogen Mycoplasma bovis type strain PG45 (used as a reference strain in many studies) revealed the presence of two tandemly positioned rrn loci (called hereinafter rrn1 and rrn2, correcting their annotations as rrn3 and rrn4 [GenBank CP002188]). Each of the two rrn genes consists of the two alleles rrs and rrl. In the M. bovis PG45 genome annotation, the genes MBOPG45_0956 and MBOPG45_0957 correspond to rrs1 and rrl1, respectively, and MBOPG45_0958 and MBOPG45_0959 to rrs2 and rrl2, respectively (8). The rrn genes are separated by five intergenic regions (IGRs): IGR-1 (located upstream of rrs1), IGR-2 (between rrs1 and rrl1), IGR-3 and IGR-4 (separating rrl1 and rrs2 and rrs2 and rrl2, respectively), and IGR-5 (located downstream of rrl2) (Fig. 1). In addition, there are two rrf genes (rrf1 and rrf2, which correspond to MBOVPG45_0980 and MBOVPG45_0981, respectively) separated by a single open reading frame (ORF), MBOVPG45_0659, encoding a putative membrane protein. Unlike many other bacteria, M. bovis rrf genes are located far from the rrs-rrl genes (about 430 kb in M. bovis PG45).

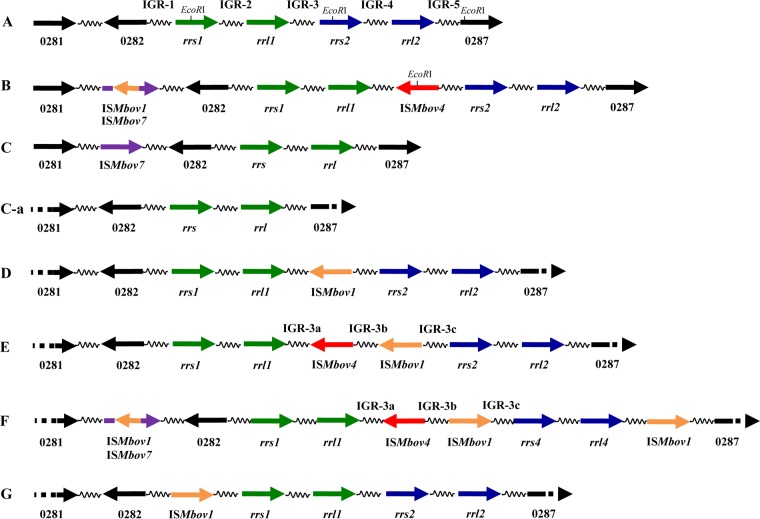

FIG 1.

Schematic representation of the genomic regions containing the ribosomal genes and their flanking regions in different M. bovis strains. The rrn loci are represented for M. bovis strains PG45 (configuration A), HB0801 or NM-2012 (B), Hubei-1 or CQ-W70 (C), 88127 (C-a), 268B07 (D), 393B08 (E), 72242 (F), and 422 (G). The locations and directions of the genes as well as intergenic regions (IGR) are shown by arrows and spiral lines, respectively. Numbers below arrows correspond to gene names from M. bovis strain PG45 (NC_014760.1 [without the prefix MBOVPG45]).

The organization of the rrn gene clusters differed in four other annotated genomes of M. bovis strains isolated in China (NZ_CP005933.1 for strain CQ-W70, NZ_CP011348.1 for NM-2012, NC_015725.1 for Hubei-1, and NC_018077.1 for HB0801). For example, only one rrs-rrl pair and a copy of an insertion sequence (IS), ISMbov7, upstream of the MBOVPG45_0282 orthologs were identified in M. bovis strains Hubei-1 (9) and CQ-W70. In the two other complete M. bovis genomes (strains HB0801 and NM-2012) available in the GenBank database, two rrs-rrl operons were present, separated from each other by the insertion of ISMbov4 (related to the IS4 gene family) into IGR-3 (10) (Fig. 1). Moreover, the insertion of ISMbov1 (related to the IS30 gene family) into ISMbov7 was identified upstream of the MBOVPG45_0282 ortholog.

ISs are widespread in prokaryotic genomes in general and in the M. bovis genome in particular, where they are found in multiple copies (11). ISs have an important impact on genome structure and function, including participation in genome rearrangements, as well as in modulation of gene expression (12). Therefore, the aims of this study were (i) to characterize the frequency and distribution of IS elements in the rrn locus of M. bovis strains, (ii) to identify where, relative to the rrn-promoter region, the insertion of the ISs occurred, and (iii) to clarify whether the presence of the IS elements influences the expression of the rrs gene and the growth rate of M. bovis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycoplasma bovis strains and growth conditions.

In this study, the configurations of the rrn loci were analyzed in 70 M. bovis field isolates for which the geographic origin and associated clinical information have been previously described (13, 14). From these 70 isolates, 32 were isolated in Israel (1995 to 2011), 13 in Germany (1978 to 1993), 11 in the United Kingdom (2000 to 2009), 1 in Cuba (1980), and 7, 3, and 3 in the Israeli quarantine station from calves imported to Israel from Hungary (2006 to 2008), Australia (2006), and Lithuania (2007 to 2008), respectively. The strains that had rrn loci characterized in this study are 88127 (isolated in Israel in 2010), 268B07 (United Kingdom, 2007), 393B08 (United Kingdom, 2008), 72242 (Israel, 2010), and 422 (Cuba, 1980) (Fig. 1); all are clonal isolate type C. Three additional strains for which complete genome sequences were available include M. bovis PG45 type strains (United States, 1961) and HB0801 and Hubei-1 (China, 2008). All isolates were propagated at 37°C in standard M. bovis broth medium (15) supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) sodium pyruvate and 0.005% (wt/vol) phenol red (16), at pH 7.8.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification of rrn loci.

M. bovis genomic DNA was extracted from 100 ml of logarithmic-phase broth cultures using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The primers were developed and commercially synthesized (Sigma, Rehovot, Israel) based on the nucleotide sequences of M. bovis type strain PG45 (NC_014760.1 [8]), strain HB0801 (NC_018077.1 [10]), and strain Hubei-1 (NC_015725.1 [9]) (Table 1). The primers MB-282-F and MB-rrl-R3 allowed amplification of the sequences containing intergenic region 1 (IGR-1) and IGR-2. Primers MB-rrs-F3 and MB-287-R allowed amplification of the sequences containing the IGR-4 and IGR-5 regions, and primers MB-rrl-F6 and MB-rrs-R3 were used to amplify sequences containing IGR-3. In addition, primers MB-282-F and MB-287-R were used to amplify the rrn locus in strains with one rrn allele (Table 1). When needed, primers complementary to the internal sequences of the amplicons were used to complete the sequence of the PCR products (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Primers and amplification conditions used in this study

| Goal | Strain(s) | Primer source | Primer or probe |

PCR programb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designation | Sequence (5′→3′)a | Annealing temp (°C) | Elongation time | |||

| Amplification of rRNA gene cluster | 268B07, 393B08, 72242, and 422 | MBOVPG45_0281 | MB-281-F1 | CAATGCAAGACCCGAAGTTT | 64 | 1 min 30 s |

| rrs1 and rrs2 | MB-rrs-R1 | GATGTTTCCATCCGCTATCC | ||||

| MBOVPG45_0282 | MB-282-F | GGATATCTAACGCCGTGTCT | 56 | 2 min | ||

| rrl1 and rrl2 | MB-rrl-R3 | GTACTGGTCAGCTCAACAC | ||||

| rrl1 and rrl2 | MB-rrl-F6 | GTACGGTCAGAAACCGTATG | 60 | 1 min | ||

| rrs1 and rrs2 | MB-rrs-R3 | GGTAGCATCATTTCCTATGC | ||||

| rrs1 and rrs2 | MB-rrs-F3 | CGAGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTC | 64 | 2 min | ||

| MBOVPG45_0287 | MB-287-R | CTAATTCCAAGTGCCACTAGCG | ||||

| 88127 | MBOVPG45_0282 | MB-282-F | GGATATCTAACGCCGTGTCT | 64 | 2 min | |

| MBOVPG45_0287 | MB-287-R | CTAATTCCAAGTGCCACTAGCG | ||||

| MBOVPG45_0281 | MB-281-F1 | CAATGCAAGACCCGAAGTTT | 64 | 1 min 30 s | ||

| rrs1 and rrs2 | MB-rrs-R1 | GATGTTTCCATCCGCTATCC | ||||

| Southern blot analysis | PG45 | rrs1 and rrs2 | MB-rrs-F4 | CCGTTCTCAGTTCGGATTGAAG | 50 | 30 s |

| MB-tet1/2-R | CGTTCTCGTAGGGATACCT | |||||

| TSS mapping | 88127, 72242, and 422 | |||||

| cDNA synthesis | rrl | MB-rrl-R1 | CGATTTTGGGACCTTAGCTG | 55 | 20 s | |

| Nested PCRs | rrs | MB-rrs-R1 | GATGTTTCCATCCGCTATCC | 55 | 20 s | |

| MB-rrs-R3 | GGTAGCATCATTTCCTATGC | |||||

| qRT-PCR | 88127, 100/91, 213, 422, 8998, 111, 3181, 3222, 72242, and 1366 | GAPDH gene (MBOVPG45_0062) | Probe for GAPDH gene | FAM-TAATGGAAAGCTTGATGGC-MGB | ||

| GAPDH Fw | TGGATTGGTTGTGCCTGAAG | |||||

| GAPDH Rv | TTGTAGGCACACGAAGTGCAA | |||||

| rrs1 and rrs2 | Probe for 16S | FAM-TTGCAAGCGTTATCC-MGB | ||||

| 16S Fw | CCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATA | |||||

| 16S Rv | CAGACGCTTTACGCCCAATAA | |||||

FAM, 6-carboxyfluorescein; MGB, minor groove binder.

Amplification was done using 40 cycles. For the qRT-PCR program conditions, see Materials and Methods.

PCRs were carried out in 50-μl volumes containing 250 ng of template DNA, 1 μl of Phire Hot Start II DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 5 × Phire reaction buffer, and 0.4 μM each primer. PCR amplifications were carried out in a C1000 series thermocycler (Bio-Rad, CA). Primer sets and conditions (annealing temperature and elongation time) for the various PCRs are specified in Table 1. All amplicons were extracted from the gels and purified using the MEGAquick-spin PCR and agarose gel DNA extraction system (iNtRON, Biotechnology, South Korea). Sequencing was performed at the DNA Sequencing Unit of The Weizmann Institute (Rehovot, Israel).

Southern blot analysis.

M. bovis strains were grown in 100 ml of broth medium to the late logarithmic stage. They were then centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 25 min, and the pellets were resuspended in Tris-NaCl (10 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl). Genomic DNA was extracted as described above. For Southern blot analysis, 3 μg of genomic DNA was digested with 10 U of EcoRI restriction enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the fragments were separated by electrophoresis in a 0.8% agarose gel. Lambda phage DNA digested with HindIII was used as a size standard. DNA was then transferred onto a positively charged nylon membrane (NytranN, Schleicher & Schuell, Germany) following a standard protocol (17). The DNA was fixed to the membrane by UV cross-linking at 700 J/cm2 (UV Stratalinker 1800; Stratagene, CA).

Primers MB-rrs-F4 and MB-tet1/2-R (Table 1) were used to amplify the M. bovis PG45 genomic fragment of 222 bp corresponding to the 3′ end of both rrs genes. The amplification parameters are presented in Table 1. The probe was subsequently labeled with digoxigenin (DIG)-11-dUTP using the PCR DIG probe synthesis kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA fragments were then hybridized to the DIG-labeled probe, washed, incubated with alkaline phosphatase (AP)-tagged anti-DIG antibody, and detected as previously described (18). Chemiluminescence detection and image acquisition were performed using a G:BOXChemi XR5 scanner (Syngene, Cambridge, United Kingdom).

RNA isolation and mapping of the transcription start site of the rRNA operon.

The nucleotide sequences of both alleles of the rrs and rrl genes had a high sequence identity, preventing us from mapping the transcription start site (TSS) of the rRNA operons in strains containing two copies of the rrn operons. To overcome this problem, M. bovis strain 88127, containing only one rrn operon, was used (Fig. 1). Total cellular RNA was extracted from mid-logarithmic-phase cultures of M. bovis 88127 using the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). The rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) technique was used to map a TSS. The 5′-RACE was carried out with a 2nd-generation 5′/3′-RACE kit, (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, cDNA was obtained using 1.8 μg of DNA-free RNA of M. bovis strain 88127 with the MB-rrl-R1 primer, which was complementary to the sequence of the rrl gene. The cDNA was cleaned using the MEGAquickspin total fragment DNA purification kit (iNtRON Biotechnology, South Korea), and an aliquot of 19 μl was used in the reaction mixture to add a homopolymeric poly(A) tail to the 3′ end of the cDNA. In the first 5′-RACE PCR, 5 μl of the cDNA product with a poly(A) tail was subjected to PCR using the forward oligo(dT) anchor primer provided by the kit and a nested rrs-specific MB-rrs-R3 reverse primer. In the second 5′-RACE PCR, an aliquot of 1 μl from the first 5′-RACE PCR was amplified using the forward PCR primer (PCR Anchor primer), provided by the kit and the reverse MB rrs-R1-specific primer. The final PCR product was purified using the MEGA quick-spin PCR and agarose gel extraction system (iNtRON Biotechnology, South Korea) and cloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). Eighteen clones carrying an insert were selected and sequenced. Analysis of the cloned sequence allowed determination of the TSS, defined as the first nucleotide following the sequence of the adapter primer. As a control for the 5′-RACE technique, we mapped the TSS of the M. bovis PG45 p48 gene, the TSS of which has been previously determined by primer extension analysis (18).

Growth rate determination of M. bovis strains with different numbers and configurations of rrs-rrl genes.

All isolates were propagated at 37°C in standard M. bovis broth medium (15) adjusted to pH 7.8 without sodium pyruvate. Growth curves were obtained by monitoring the number of viable cells in the logarithmic phase at 8, 12, and 16 h postinoculation (hpi). M. bovis strains were inoculated into 215 ml of M. bovis broth in order to obtain an initial bacterial density of approximately 103 CFU per μl. Aliquots of 100 μl were taken from each culture at 8, 12, and 16 hpi, and 10-fold serial dilutions (10−1 to 10−5) were carried out in M. bovis broth medium. Five microliters from each of the selected dilutions was plated on M. bovis agar in triplicate. Colony counting was performed after 5 days of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, and the number of CFU was estimated for each time point. The experiment was repeated three times for each strain.

The growth rate determination as well as relative quantification of the 16S rRNA expression (see below) were performed on four different groups of M. bovis strains containing (i) two rRNA operons (strains 8998, 111, and 3181; configuration A), (ii) one rRNA operon (strains 88127, 213, and 100/91; configuration C-a), (iii) two rRNA operons with insertion of ISMbov1 within IGR-1 (strains 422 and 3222; configuration G), and (iv) two rRNA operons with insertion of both ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 within IGR3 and ISMbov1 in IGR-5 (strains 72242 and 1366; configuration F). The log10 concentration of M. bovis was calculated at each time point to quantify the growth rate of each of the four groups.

Relative quantification by real-time RT-PCR of rrs gene expression in M. bovis strains with different numbers and configurations of the rrn loci. (i) RNA isolation.

To quantitate the expression of the rrs genes, 25 to 150 ml of cultured bacteria (depending on the time point) was collected at the same time points used for the growth rate determination trial (8, 12, and 16 hpi). The cultures were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 25 min, supernatants were discarded, and the pellets were frozen at −80°C. Extraction of total M. bovis RNA was done with the High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were treated with RNase-free DNase I (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA was finally dissolved in 50 μl of RNase-free water. One microliter of RNase inhibitor (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) was added to stabilize extracted RNA. The RNA concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE), and the preparation was stored at −80°C.

(ii) cDNA synthesis.

Equal amounts of total RNA (50 ng) from each sample were subjected to cDNA synthesis using a Life Technologies high-capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit. Briefly, the cDNA reaction was performed with 0.5 μl of 20× enzyme mixture, 5 μl of 2× buffer, and up to 4.5 μl total RNA (50 ng) in a final volume of 10 μl. The cDNA reactions were carried out using a C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, CA). The reaction mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, then heated for 5 min at 95°C, and then rapidly cooled to 4°C. The cDNA was finally diluted at a ratio of 1:100 in ultrapure water (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel), and 1 μl of RNase inhibitor (New England BioLabs, United Kingdom) was added. The samples were stored at −20°C until used.

(iii) qRT-PCR.

The relative concentrations of rrs gene transcripts were quantified using quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with gene-specific primers and TaqMan-MGB (minor groove binder) probes (Rhenium, Israel) (Table 1). PCR primers and probes for qRT-PCR were designed using Primer Express 1.0 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The gene encoding the enzyme glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; MBOVPG45_0062) was used as the standard reference gene (Table 1). The amplicons' expected size and the absence of nonspecific products were confirmed by conventional PCR with the same primers. Real-time PCR efficiency data were obtained by amplifying a dilution series of cDNA and analyzing the results using the equation E = 10(−1/slope) (19).

16S rRNA gene expression was determined at 8, 12, and 16 hpi in the four different groups of strains (2 to 3 strains per group) described above. The assay was performed on the StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR mixture contained 2 μl of cDNA, 5 μl of TaqMan Fast Advanced master mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and 0.5 μl of the designed Custom TaqMan copy number assays (including either primers 16S Fw and 16S Rv and probe for the 16S rRNA or primers GAPDH Fw and GAPDH Rv and probe for the GAPDH gene [Table 1]) in a final volume of 10 μl. The reaction conditions were as follows: 20 s at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 1 s at 95°C and 20 s at 60°C. A nontemplate control using double-distilled water (Biological Industries, Beit Haemek, Israel) was included in each run. For each strain, three independent experiments were conducted, and all qRT-PCRs were performed in triplicate. Variability between runs was normalized using StepOnePlus (v2.2.2). The average threshold cycle (CT) was calculated for triplicates of the same samples, and relative expression was calculated for each sample using the 2ΔΔCT method, where ΔΔCT = ΔCT(rrstreat − GAPDHtreat) − ΔCT(rrscontrol − GAPDHcontrol) (20). The ΔCT control was calculated for each time point (8, 12, and 16 hpi) as the average CT value of triplicates from three independent experiments for three M. bovis strains (9 replicates per strain) included in the group of strains possessing two rrn operons (configuration A).

Statistical analysis.

To assess the difference in levels of rrs gene expression between different M. bovis groups throughout the time course of the experiment, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan's post hoc test was used. Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). Measurements were considered significantly different if P was < 0.05.

Accession number(s).

Sequence editing, consensus, and alignment construction were performed using DNASTAR, version 5.06/5.51, 2003 (Lasergene, Inc., Madison, WI) and BioEdit (Ibis Biosciences) (21). The nucleotide sequences of representative rrn loci (from the 3′ end of the MBOVPG45_0281-like ortholog up to the 5′ end of the MBOVPG45_0287-like ortholog) have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. KX687007 to KX687011, corresponding to the rrn loci of M. bovis strains 88127, 422, 268B07, 393B08, and 72242, respectively.

RESULTS

Identification of IS elements within the M. bovis rRNA gene cluster.

Molecular characterization, by PCR, of rrn gene loci in 70 M. bovis field isolates revealed the presence of insertion sequences (ISs that carry a complete transposase gene or its pseudogene) within different IGRs in 35 of 70 M. bovis field isolates. The ISs belonged to the ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 families, which have previously been shown to be widely distributed in the M. bovis type strain PG45 genome (11, 22). The insertion of ISMbov1 within IGR-1 or IGR-3 was identified in three and six M. bovis isolates, respectively, while the insertion of ISMbov4 was found in IGR-3 of 18 M. bovis isolates. In addition, eight isolates contained insertions of two elements (ISMbov1 and ISMbov4) within IGR-3; among those eight isolates, four also had an insertion of ISMbov1 within IGR-5 (data not shown).

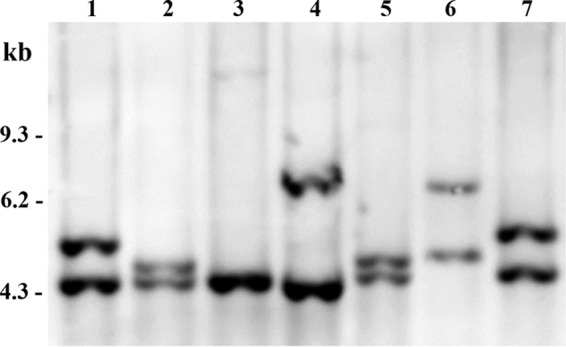

Various rrn configurations relative to the ISs, as well as differences in the numbers of rrn operons, were also shown by Southern blotting (Fig. 2 and data not shown). Genomic DNAs of M. bovis representative strains digested with EcoRI were probed with a 222-bp fragment present in both of the rrs genes, and variation in the sizes and numbers of EcoRI-digested fragments was detected (Fig. 2). Overall, seven different rrn operon configurations with respect to type and insertion site of ISs were recognized, including those found in the sequenced genomes of M. bovis PG45, HB0801 (or NM-2012), and Hubei-1 (or CQ-W70). Notably, while the sizes of the EcoRI-digested genomic fragments containing the rRNA genes were similar in strains 341B09 (which had a HB0801-like configuration of the rrn locus) and 393B08, as well as in PG45 and 422 (Fig. 2), the sequences of their rrn loci differed (Fig. 1 [see below]). In addition, despite the fact that M. bovis strain 88127 had only one rrn operon, like strain Hubei-1, it did not contain ISMbov7 upstream of the MBOVPG45_0282 ortholog (Fig. 1 and 2 [see below]).

FIG 2.

Southern blot hybridization of representative M. bovis strains showing different configurations and numbers of rrn. Molecular size markers are indicated on the left of the panel. The M. bovis strains are as follows (by lane): 1, PG45; 2, 341B09 (equivalent of HB0801 strain for the rrn configuration); 3, 88127 (equivalent of Hubei-1 strain for the rrn configuration, but without ISMbov7 upstream of MBOV_0282); 4, 268B07; 5, 393B08; 6, 72242; and 7, 422.

We further sequenced a region located between the 3′ end of the MBOVPG45_0281 orthologs and the 5′ end of the MBOVPG45_0287 orthologs (with an overall size of about 6.6 to 19.2 kb, depending on the strain) in M. bovis strains 88127, 268B07, 393B08, 72242, and 422. Analysis of the rrn locus (designated as a sequence lying between the 3′ end of MBOVPG45_0282 and the 5′ end of MBOVPG45_0287) revealed the presence of four new configurations (D for 268B07, E for 393B08, F for 72242, and G for 422, with configurations A to C corresponding to M. bovis PG45, HB0801 and NM2012 and the Hubei-1 and CQ-W70 strains, respectively). The configuration of the rrn locus of M. bovis strain 88127 was designated C-a as it was the same as that in the M. bovis Hubei-1 strain but did not contain the ISMbov7 upstream of the MBOVPG45_0282 ortholog (Fig. 1). The differences between the D-to-G configurations were (i) the presence of ISMbov1 in IGR-3 in configuration D, (ii) insertion of ISMbov4 and ISMbov1 in IGR-3 in configuration E, with both ISs in the opposite direction to that of rRNA genes, (iii) insertion of ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 in IGR-3 and ISMbov1 in IGR-5 in configuration F, with ISMbov4 in the opposite direction to ISMbov1 and to the rRNA genes, and (iv) insertion of ISMbov1 in IGR-1 in configuration G (Fig. 1).

The ORF of a putative membrane-associated protein described in the genome of PG45 (MBOVPG45_0659) was identified as separating the two copies of the 5S rRNA gene (rrf1 and rrf2) in the M. bovis annotated genomes, as well as in all of the strains tested in this study (data not shown). There were no insertions of IS elements upstream or downstream of rrf genes in M. bovis strain HB0801, NM-2012, Hubei-1, CQ-W70, 88127, 72242, or 422. However, insertion of ISMbov1 upstream of rrf2 (strains PG45 and 268B07) or downstream of rrf1 (strain 393B08) was detected. An insertion of ISMbov1 upstream of rrf2 occurred within the MBOVPG45_0662-like orthologs, resulting in the truncation of this ORF, which is conserved in many Mollicutes, as well as other pathogenic bacteria, including Chlamydia and Campylobacter species. Interestingly, truncated versions of the MBOVPG45_0662 orthologs were found in strains 393B08 and 422, which did not contain insertion of ISMbov1 upstream of rrf2, while in other strains (HB0801, NM-2012, Hubei-1, CQ-W70, 88127, 72242) without this insertion, the full version of this ORF was found (data not shown).

Only 5 of 70 M. bovis strains tested contained one rrs-rrl in configuration “C-a.” As the sequences of the two alleles of rrs and rrl, as well as IGR-2 and IGR-4, were almost identical, it was not possible to conclude with a high level of confidence whether the rrn1 or rrn2 operon was present in genomes of the M. bovis strains 88127 and Hubei-1, which contain only one rrn operon. Therefore, the structure of the rrn locus in those strains can only be presented as follows: IGR-1 followed by rrs1/2, IGR-2/4, rrl1/2, and IGR-5.

Sequence analysis of intergenic regions and molecular characterization of ISMbov4 and ISMbov1 insertion sites.

Sequence analysis of the five IGRs associated with the rrn1 and rrn2 loci of the M. bovis PG45 genome revealed 99% identity match (307 of 309 nucleotides [nt]) between IGR-2 and IGR-4 and 97.7% identity match in the first 90 nt of the 5′ end of IGR-3 and of the 5′ end of IGR-5. In addition, 97% identity match was detected between the last 74 nt of the 3′ ends of IGR-1 and IGR-3 (data not shown). Analysis of the nucleotide sequences that flank M. bovis HB0801-ISMbov4 in configuration B (IGR-3) and ISMbov4 in configuration F (IGR-3a and IGR-3b; strain 72242) revealed its terminal 13-bp inverted repeats (IRs) with two mismatches (5′-TATAAAAGTTATA-3′ and 5′-TAAAACTTTTTTA-3′), as well as the 6-bp-long direct repeats (DRs) (5′-TTTTAT-3′) that are proposed to be a result of an IS target duplication. The same IRs and DRs were identified in IGR-3a and IGR-3c of configuration E (393B08), in which ISMbov4 was located upstream of ISMbov1 (Fig. 1). The sequence 5′-TTTTAT-3′ that served as a target site for ISMbov4 insertion (DR) was also identified three times at different positions within IGR-2, IGR-3, IGR-4, and IGR-5, as well as twice within IGR-1, in the M. bovis PG45 rrn locus.

Analysis of nucleotide sequences flanking the left and right termini of ISMbov1 elements revealed the presence of the 14-bp DRs 5′-AAAAGTTTGAAAAT-3′ in configuration D (268B07), 5′-AAATAAAATTAATT-3′ in configuration E (in IGR-3b and IGR-3c; strain 393B08), 5′-AAAATATTTATTAA-3′ in IGR-3b and IGR-3c, 5′-ACTATCAAATAAAA-3′ in IGR-5 in configuration F (72242), and 5′-AAATGCAAATTTAT-3′ in IGR-1 in configuration G (strain 422) (Fig. 1). The IRs of ISMbov1 isomers found in rrn loci were 5′-TAT-3′ as previously described (11, 22).

Mapping of transcriptional start sites of rrn operons.

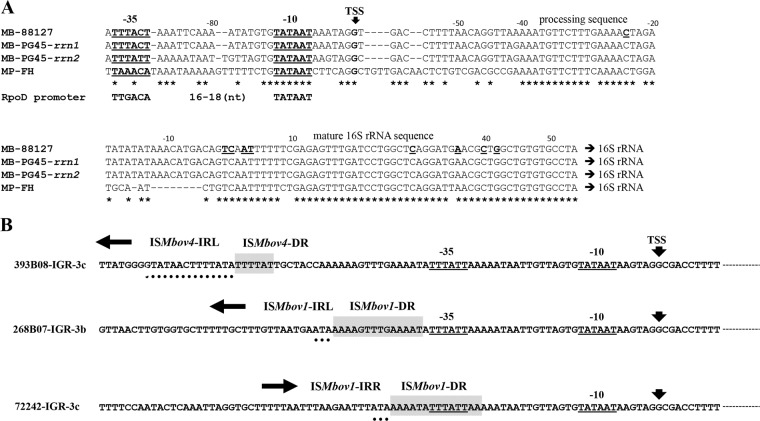

Due to the high homology between the two copies of rrs as well as between rrl genes, it was not possible to determine a transcriptional start site (TSS) for each of the alleles. Therefore, the TSS of the rrn operon was further examined in M. bovis strain 88127, the genome of which was found in this study to contain only one pair of rrs-rrl genes. The analysis of 18 independent amplicons revealed that their 5′ ends varied in length. The longest sequence was mapped to begin with a guanine nucleotide within IGR-1 60 nt upstream of the rrs gene. It was preceded by the sequence 5′-TATAAT-3′, which was identical to a typical bacterial RpoD (σA)-dependent promoter −10 element and by a putative −35 element sequence (TTtACt; where lowercase letters indicate two mismatches compared to the RpoD promoter consensus motif, TTGACA) (Fig. 3A). Putative RNA processing products with 5′ ends mapped to 24 (n = 2) and 1 (n = 3) nt upstream of the rrs gene and 1 (n = 1), 3 (n = 6), 4 (n = 1), 29 (n = 1), 36 (n = 1), 40 (n = 1), and 42 (n = 1) nt within the rrs gene were also found (Fig. 3A). These different transcript lengths suggested an initial pre-16S rRNA and processed and mature RNA products (23). The rrs and rrl genes appeared to be cotranscribed as a polycistronic mRNA as our attempts to map a separate TSS for the M. bovis strain 88127 rrl did not succeed (data not shown). Based on the results described above, as well as the high homology between the 3′ ends of IGR-1 and IGR-3 sequences in M. bovis genomes carrying two copies of the rrn operons, both the TSS and potential promoter region for the second rrn2 operon were also predicted (Fig. 3A).

FIG 3.

M. bovis rrn promoter region and IS insertion. (A) The promoter region for the M. bovis 88127 rrn operon, as determined by 5′-RACE. Part of the nucleotide sequence of the rrs gene and its upstream region is shown. The position of the transcriptional start site (arrowhead) and the sequences corresponding to prokaryotic RpoD (σA)-dependent promoter −10 element and −35 element sequences are in boldface and underlined. The positions of the 5′ ends of potential processed and mature rrs products, identified by 5′ RACE, are shown in boldface and underlined. The same (TSS, −10, and −35) promoter elements were predicted in rrn1 and rrn2 of M. bovis PG45. In addition, the promoter region of the M. pneumoniae FH strain rrn operon as determined by Hyman et al. (43) is also shown. Identical nucleotides are marked by asterisks. (B) Analysis of IS insertion relative to the promoter region of the rrn2 operon. The nucleotide sequences of the rrn2 promoter region of M. bovis strains 393B08, 268B07, and 72242 are shown. The positions of the predicted transcriptional start site (arrowheads) and both promoter −10 and −35 sequence motifs are shown in boldface and underlined. The arrows show the orientations of the ISs. The ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 inverted repeats (IRs) are indicated by dots, and the target site duplications generated by IS transposition (direct repeats [DR]) are shaded in gray.

Relative to the predicted TSSs of rrn1 and rrn2, the target sites for the ISMbov4 insertions were identified at position −60 bp in M. bovis strains 393B08 and HB0801, while the target sites for the ISMbov1 insertions were identified at −28, −37, and −149 bp in M. bovis strains 72242, 268B07, and 422, respectively (Fig. 3B). Notably, only 1 nt separated the target site of ISMbov1 and a potential promoter −35 sequence in configuration D (strain 268B07), whereas 24 bp separated them in configuration E (ISMbov4; strain 393B08), while in configuration F (strain 72242), the −35 consensus sequence was part of an ISMbov1 target DR (Fig. 3B).

We further tested whether insertion of IS elements upstream of the promoter region of the rrn operon provided an additional promoter for rrs and rrl genes. However, the 5′-RACE PCR applied to M. bovis strains 72242 and 422 (configurations F and G, respectively) did not reveal any additional promoters (see above).

Relative quantitation of rrs expression in groups of M. bovis strains with different numbers and configurations of the rrn loci.

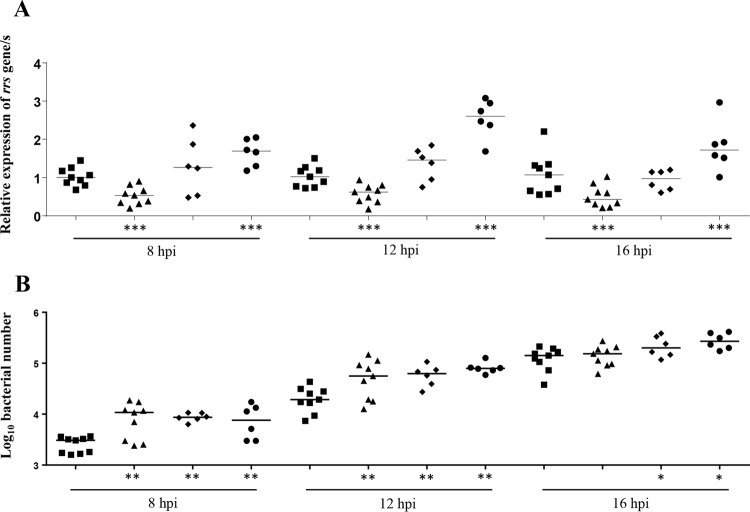

The level of expression of the rrs gene was significantly lower (P < 0.0001) in the strains containing one rrn operon (configuration C-a) than in the strains containing two rrn operons (configuration A) and significantly higher (P < 0.0001) in the strains containing two rrn operons with the insertion of ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 within IGR-3 and ISMbov1 in IGR-5 (configuration F) for all three time points (Fig. 4A). No differences in the expression of the rrs genes were identified between strains with configurations G (insertion of ISMbov1 in IGR-1) and A at any time point. However, while no differences in the expression of rrs were found between strains in configurations G and F at 8 hpi, the former had a significantly lower level of expression at 12 and 16 hpi (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Relative expression of rrs genes (A) and growth rates (B) in M. bovis strains with different numbers and configurations of rrn loci. Strains with two rrn operons (configuration A [squares]), one rrn (configuration C-a [triangles]), with an insertion of ISMbov1 within IGR-1 (configuration G [diamonds]), or with the insertion of ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 within IGR-3 and ISMbov1 in IGR-5 (configuration F [circles]) at 8, 12, and 16 hpi are shown. The y axes indicate expression levels of rrs relative to control group (configuration A at each time point) (A) or growth rate expressed as log10 CFU per microliter (B). The results of qRT-PCR were normalized against the GAPDH gene expression used as an internal control. Relative levels of rrs mRNA were analyzed by the 2ΔΔCT method. The data presented are values from groups containing six or nine strains, with medians indicated as horizontal bars. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*, P ≤ 0.01; **, P ≤ 0.001; ***, P ≤ 0.0001) among strains in configurations C-a, F, and G versus the group of M. bovis strains in configuration A calculated by one-way ANOVA with Duncan's post hoc test.

Growth rates of M. bovis strains with different numbers and configurations of the rrn loci.

The growth rates of all groups of strains (configurations C-a [one rrn operon], F [two rrn operons with the insertion of ISMbov1 and ISMbov4 within IGR-3 and ISMbov1 in IGR-5], and G [insertion of ISMbov1 in IGR-1]) were significantly higher (P ≤ 0.001) at 8 and 12 hpi in comparison to the growth rates of the group with two rrn operons (configuration A), but no significant difference was noticed between strains with configurations C-a, F, and G (Fig. 4B). At 16 hpi, the growth rates of strains with configuration G or F were significantly higher than for those with configuration A or C-a, but no difference was seen between strains with configurations A and C-a or between those with configurations G and F.

DISCUSSION

Data generated in this study showed a high prevalence of diverse ISs within the M. bovis rrn locus resulting in intraspecies variability. Half of the M. bovis isolates contained an IS element or elements from two different IS gene families (IS4 and IS30), within their rrn operons, with most of the insertions occurring within IGR-3 alone (80%), within IGR-3 and IGR-5 (11.4%), or within IGR-1 (8.6%). Insertions of ISs usually occur within AT-rich regions, so their presence within the IGRs is not surprising as they have an AT content ranging, at least in M. bovis PG45, from 75% to 80%. However, it is difficult to explain why so many insertions were observed within IGR-3, which separates the two rrn operons (Fig. 1). The presence of IS elements within or close to the rrn locus was also detected in the annotated genomes of other Mycoplasma species, including the Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC type strain PG1 (between the tRNA-Leu and rrs genes), Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae 168 (downstream of the rrn operon), Mycoplasma agalactiae 5632 (upstream of and close to the promoter region of one of the rrn operons), and Mycoplasma imitans type strain 4229 (within the IGR located between the 16S and 23S RNA genes) (24–27). Notably, in the case of M. bovis (and probably the closely related species M. agalactiae) the insertion of ISs was upstream or within the promoter region of one of the rrn operons (Fig. 1 and 3). In three M. bovis strains (393B08, 268B07, and 72242), the IS insertion occurred in close proximity to or even within the predicted promoter −35 sequence of rrn2 (Fig. 3B).

The high prevalence of IS elements within or close to the M. bovis rrn operons raises a question of whether their location is coincidental or if it might have a biological role. IS elements may influence expression of neighboring genes through putative cryptic promoters located in their 3′- and 5′-terminal regions, by the formation of hybrid promoters, or through disruption of transcriptional repression or activation. For example, many IS elements affect expression of downstream genes encoding resistance to antimicrobials (28, 29). AmpC-type cephalosporinase overexpression resulted from insertion of IS1133-like elements (designated ISAba1) upstream of the blaampC gene in ceftazidime-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates (30, 31). It has been shown that insertion of ISAba1 provides a strong promoter that increases expression of the blaampC gene (30, 31). Similarly the flhDC operon of E. coli K-12, which is a part of the flagellar regulon and a global regulator of metabolism (32), is expressed at increased levels as a result of spontaneous insertion of either an IS1 element (in strain MG1655) or IS5 element (strain W3110) within its regulatory region, resulting in increased motility (33). Primer extension performed on these strains determined that the transcriptional start site of flhD was unaltered by insertion of the IS element. The authors suggested that IS insertion may activate transcription of the flhD operon by reducing transcriptional repression (33).

Our attempts to map an IS-related TSS for the rrn operons in M. bovis strains 72242 and 422 (configurations F and G, respectively) were not successful. This may be because either IS insertion in these strains did not introduce an additional promoter or because the promoter was not very strong. In addition, the high homology between the two copies of M. bovis rrn operons made mapping of the 5′ ends also problematic. Unfortunately, we could not identify M. bovis strains with one rrn copy with an insertion of an IS close to or in the promoter region of the rrs gene. Interestingly, we detected a significant increase in expression of the rrs genes, as well as an increase in growth rate in the strains with an IS element insertion within a putative promoter −35 sequence (configuration F) compared to strains with one or two rrn operons that did not have an IS insertion (Fig. 4). Therefore, we suggest that at least in configuration F and under the conditions tested in our study, there is a relationship between IS elements and rrs expression. However, the expression of the rRNA genes and growth of bacteria are complex processes that are influenced by different environmental/experimental factors, as well as by other genomic regions. So, more work needs be done to clarify whether the insertion of an IS close to or within the promoter region of an M. bovis rrn operon influences the expression of the rRNA genes and if these changes have an effect on the RNA and protein content.

Our results support the data obtained from annotated genomes of the two Chinese M. bovis strains Hubei-1 and CQ-W70, showing the presence of only one rrn operon in their genomes. Indeed, 7% of the strains tested in our study possessed only one rrn operon. It has previously been shown that the copy numbers of rrn operons may vary from strain to strain within the same species. For example, different Vibrio cholerae strains contain 7, 8, or 9 rrn operons (34). One of the possible explanations of copy number variation among strains of the same species is a recombination between rrn operon copies in the same direction, leading to both a reduction in genome size and elimination of a copy of the rrn operon (34–38). The other possible explanation is homologous recombination between ISs. Dispersal of IS isoforms throughout the genome, as well as their high homology, allows them to be involved in homologous recombination or in DNA rearrangements that can influence genomic variability (39) and may also influence the structure and the number of rrn operons.

The rrn copy number influences rRNA availability, and as a consequence, the number of functional ribosomes in the cell. It is generally assumed that prokaryotic rrn copy number reflects the organism's ecological strategy and that rapidly growing bacteria with a large genome usually have higher rrn operon copy numbers (40, 41). Different rrn operon copy numbers might be beneficial under variable environmental conditions, as has been previously shown in isogenic E. coli variants containing 5 to 10 rrn operons (7 rrn operons are found in the wild type) (42); 7 to 8 copies were optimal under nutrient-rich conditions, while lower numbers (5 to 6) were favored in nutrient-limited environments. Interestingly, although we detected a significant increase in the expression of the rrs in strains with two rrn operons in comparison to strains with one rrn operon, the growth rate was higher in the latter group—at least at 8 and 12 hpi (Fig. 4). There may be several explanations for these data. (i) There is no straight relationship between rrs expression and M. bovis growth. (ii) There is some compensation mechanism that allows strains with one rrn operon to grow faster than strains with two rrn operons—at least in the early log phase (8 and 12 hpi). In addition, we did not check for an impact of the rrf genes and their surroundings (presence/absence of IS elements upstream or downstream of rrf alleles) on the expression of the rrs genes and the growth rate.

In conclusion, our data show a high prevalence of diverse ISs within the M. bovis rrn locus resulting in intraspecies variability. This high prevalence of IS elements within or close to the M. bovis rrn-operon-promoter region may indicate that mobile elements have an important role in the regulation of both ribosome synthesis and function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to R. Nir-Paz, Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, Israel, for help with the interpretation of qRT-PCR results.

This research was supported by a research grant in the frame of the Emerging and Major Infectious Diseases of Livestock (EMIDA) Consortium from the Chief Scientist, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, Israel (847-0369), and the Israel Dairy Board (847-0366).

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin JF, Barreiro C, Gonzalez-Lavado E, Barriuso M. 2003. Ribosomal RNA and ribosomal proteins in corynebacteria. J Biotechnol 104:41–53. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glaser G, Cashel M. 1979. In vitro transcripts from the rrnB ribosomal RNA cistron originate from two tandem promoters. Cell 16:111–121. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson SG, Zomorodipour A, Winkler HH, Kurland CG. 1995. Unusual organization of the rRNA genes in Rickettsia prowazekii. J Bacteriol 177:4171–4175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor DE, Ge Z, Purych D, Lo T, Hiratsuka K. 1997. Cloning and sequence analysis of two copies of a 23S rRNA gene from Helicobacter pylori and association of clarithromycin resistance with 23S rRNA mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:2621–2628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ellwood M, Nomura M. 1980. Deletion of a ribosomal ribonucleic acid operon in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 143:1077–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loughney K, Lund E, Dahlberg JE. 1983. Deletion of an rRNA gene set in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol 154:529–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rainey FA, Ward-Rainey NL, Janssen PH, Hippe H, Stackebrandt E. 1996. Clostridium paradoxum DSM 7308T contains multiple 16S rRNA genes with heterogeneous intervening sequences. Microbiology 142:2087–2095. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-8-2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wise KS, Calcutt MJ, Foecking MF, Roske K, Madupu R, Methe BA. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Mycoplasma bovis type strain PG45 (ATCC 25523). Infect Immun 79:982–983. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00726-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Y, Zheng H, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Xin J, Chen W, Song Z. 2011. The complete genome sequence of Mycoplasma bovis strain Hubei-1. PLoS One 6:e20999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi J, Guo A, Cui P, Chen Y, Mustafa R, Ba X, Hu C, Bai Z, Chen X, Shi L, Chen H. 2012. Comparative geno-plasticity analysis of Mycoplasma bovis HB0801 (Chinese isolate). PLoS One 7:e38239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lysnyansky I, Calcutt MJ, Ben-Barak I, Ron Y, Levisohn S, Methe BA, Yogev D. 2009. Molecular characterization of newly-identified IS3, IS4 and IS30 insertion sequence-like elements in Mycoplasma bovis and their possible roles in genome plasticity. FEMS Microbiol Lett 294:172–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siguier P, Gourbeyre E, Chandler M. 2014. Bacterial insertion sequences: their genomic impact and diversity. FEMS Microbiol Rev 38:865–891. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amram E, Mikula I, Schnee C, Ayling RD, Nicholas RAJ, Rosales RS, Harrus S, Lysnyansky I. 2015. 16S rRNA gene mutations associated with decreased susceptibility to tetracycline in Mycoplasma bovis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:796–802. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03876-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lerner U, Amram E, Ayling RD, Mikula I, Gerchman I, Harrus S, Teff D, Yogev D, Lysnyansky I. 2014. Acquired resistance to the 16-membered macrolides tylosin and tilmicosin by Mycoplasma bovis. Vet Microbiol 168:365–371. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosengarten R, Behrens A, Stetefeld A, Heller M, Ahrens M, Sachse K, Yogev D, Kirchhoff H. 1994. Antigen heterogeneity among isolates of Mycoplasma bovis is generated by high-frequency variation of diverse membrane surface proteins. Infect Immun 62:5066–5074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hannan PCT, Windsor GD, de Jong A, Schmeer N, Stegemann H. 1997. Comparative susceptibilities of various animal-pathogenic mycoplasmas to fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 41:2037–2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lysnyansky I, Yogev D, Levisohn S. 2008. Molecular characterization of the Mycoplasma bovis p68 gene, encoding a basic membrane protein with homology to P48 of Mycoplasma agalactiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 279:234–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfaff MW. 2004. Quantification strategies in real-time PCR, p 87–112. In Bustin SA. (ed), A-Z of quantitative PCR. International University Line, La Jolla, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmittgen TD. 2001. Real-time quantitative PCR. Methods 25:383–385. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall TA. 1999. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp Ser 41:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas A, Linden A, Mainil J, Bischof DF, Frey J, Vilei EM. 2005. Mycoplasma bovis shares insertion sequences with Mycoplasma agalactiae and Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC: evolutionary and developmental aspects. FEMS Microbiol Lett 245:249–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deutscher MP. 2009. Maturation and degradation of ribosomal RNA in bacteria. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 85:369–391. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6603(08)00809-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harasawa R, Pitcher DG, Ramirez AS, Bradbury JM. 2004. A putative transposase gene in the 16S-23S rRNA intergenic spacer region of Mycoplasma imitans. Microbiology 150:1023–1029. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26629-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu W, Feng Z, Fang L, Zhou Z, Li Q, Li S, Luo L, Wang L, Chen H, Shao G, Xiao S. 2011. Complete genome sequence of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae strain 168. J Bacteriol 193:1016–1017. doi: 10.1128/JB.01305-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nouvel L, Sirand-Pugnet P, Marenda M, Sagne E, Barbe V, Mangenot S, Schenowitz C, Jacob D, Barre A, Claverol S, Blanchard A, Citti C. 2010. Comparative genomic and proteomic analyses of two Mycoplasma agalactiae strains: clues to the macro- and micro-events that are shaping mycoplasma diversity. BMC Genomics 11:86. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Westberg J, Persson A, Pettersson B, Uhlen M, Johansson KE. 2002. ISMmy1, a novel insertion sequence of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony type. FEMS Microbiol Lett 208:207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato N, Yamazoe K, Han CG, Ohtsubo E. 2003. New insertion sequence elements in the upstream region of cfiA in imipenem-resistant Bacteroides fragilis strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:979–985. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.3.979-985.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poirel L, Decousser JW, Nordmann P. 2003. Insertion sequence ISEcp1B is involved in expression and mobilization of a bla(CTX-M) beta-lactamase gene. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 47:2938–2945. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2938-2945.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corvec S, Caroff N, Espaze E, Giraudeau C, Drugeon H, Reynaud A. 2003. AmpC cephalosporinase hyperproduction in Acinetobacter baumannii clinical strains. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:629–635. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segal H, Nelson EC, Elisha BG. 2004. Genetic environment and transcription of ampC in an Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolate. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:612–614. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.612-614.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu X, Matsumura P. 1994. The FlhD/FlhC complex, a transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli flagellar class II operons. J Bacteriol 176:7345–7351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barker CS, Pruss BM, Matsumura P. 2004. Increased motility of Escherichia coli by insertion sequence element integration into the regulatory region of the flhD operon. J Bacteriol 186:7529–7537. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7529-7537.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lan R, Reeves PR. 1998. Recombination between rRNA operons created most of the ribotype variation observed in the seventh pandemic clone of Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 144:1213–1221. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pébay M, Roussel Y, Simonet J-M, Decaris B. 1992. High-frequency deletion involving closely spaced rRNA gene sets in Streptococcus thermophilus. FEMS Microbiology Lett 98:51–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb05488.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Acinas SG, Marcelino LA, Klepac-Ceraj V, Polz MF. 2004. Divergence and redundancy of 16S rRNA sequences in genomes with multiple rrn operons. J Bacteriol 186:2629–2635. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2629-2635.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gurtler V. 1999. The role of recombination and mutation in 16S-23S rDNA spacer rearrangements. Gene 238:241–252. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurtler V, Mayall BC. 2001. Genetic transfer and genome evolution in MRSA. Microbiology 147:3195–3197. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-12-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chandler D, Mahillon J. 2002. Insertion sequences revisited, p 305–366. In Craig NL, Craigie R, Gellert M, Lambowitz A (ed), Mobile DNA II. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klappenbach JA, Dunbar JM, Schmidt TM. 2000. rRNA operon copy number reflects ecological strategies of bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1328–1333. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1328-1333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoddard SF, Smith BJ, Hein R, Roller BR, Schmidt TM. 2015. rrnDB: improved tools for interpreting rRNA gene abundance in bacteria and archaea and a new foundation for future development. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D593–D598. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gyorfy Z, Draskovits G, Vernyik V, Blattner FF, Gaal T, Posfai G. 2015. Engineered ribosomal RNA operon copy-number variants of E. coli reveal the evolutionary trade-offs shaping rRNA operon number. Nucleic Acids Res 43:1783–1794. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hyman HC, Gafny R, Glaser G, Razin S. 1988. Promoter of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae ribosomal RNA operon. J Bacteriol 170:3262–3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bercovier H, Kafri O, Sela S. 1986. Mycobacteria possess a surprisingly small number of ribosomal RNA genes in relation to the size of their genome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 136:1136–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]