Abstract

Caregiving stress has been associated with changes in the psychological and physical health of parents of children with cancer, including both partnered and single parents. While parents who indicate “single” on a demographic checklist are typically designated as single parents, a parent can be legally single and still have considerable support caring for an ill child. Correspondingly, an individual can be married/partnered and feel alone when caring for a child with serious illness. In the current study, we report the results from our exploratory analyses of parent self-reports of behavior changes during their child’s treatment. Parents (N = 263) of children diagnosed with cancer were enrolled at 10 cancer centers. Parents reported significant worsening of all their own health behaviors surveyed, including poorer diet and nutrition, decreased physical activity, and less time spent engaged in enjoyable activities 6 to 18 months following their child’s diagnosis. More partnered parents found support from friends increased or stayed the same since their child’s diagnosis, whereas a higher proportion of lone parents reported relationships with friends getting worse. More lone parents reported that the quality of their relationship with the ill child’s siblings had gotten worse since their child’s diagnosis. Spiritual faith increased for all parents.

Keywords: health behavior, pediatric cancer, caregivers, psychosocial, spiritual faith, relationships

All parents are intensely affected by a child’s cancer diagnosis regardless of their baseline functioning. Many parents are resilient and well functioning. For these parents, pediatric cancer can cause significant but temporary distress, after which they usually adapt to a “new normal” including the reality of the child’s cancer. For a smaller, at-risk subgroup of parents (for which risk factors are not completely understood), a child’s diagnosis of cancer can be overwhelming. In these families, the parent’s own needs and distress may affect parenting, child well-being, and family functioning across the illness trajectory (Kearney, Salley, & Muriel, in press).

Importantly, parents of children with cancer also report significantly decreased health-related quality of life as compared with population norms (Klassen et al., 2008) due to increased caregiving responsibilities and numerous stressors associated with their illness. These stressors include financial burden, role strain, separations, interruptions in daily routines, poor sleep, and uncertainty regarding the child’s prognosis (Brown et al., 2008; McLoone, Wakefield, Yoong, & Cohn, 2013; Rabineau, Mabe, & Vega, 2008; Rosenberg-Yunger et al., 2013; Wakefield, McLoone, Evans, Ellis, & Cohn, 2014). Spiritual beliefs can often buffer caregiving stress; however, parents’ religious faith may be challenged as they watch the suffering their child endures and find it difficult to reconcile their spiritual beliefs (Ennis-Durstine & Brown, in press). Although not all caregivers will identify spiritual or religious beliefs as influences on their health or adaptation to illness, a spiritual/religious orientation, or lack thereof, may influence feelings about the meaning of life, coping, justice/fairness, guilt, altruism, and attitudes toward medical care (Dell & Grossoehme, 2015). Caregiving stress has also been associated with changes in the psychological and physical health of both partnered and single parents of children with cancer (Rosenberg-Yunger et al., 2013).

Parental coping is both an individual and an interpersonal process and study findings have indicated that various forms of avoidance and disengagement (eg, denial, passivity) are associated with greater emotional distress (Bennett Murphy et al., 2008; Greening & Stoppelbein, 2007; Maurice-Stam et al., 2008). The significant positive correlations between partners’ reports of disengagement coping and their depressive symptoms suggest that some couples may be characterized by more maladaptive coping mechanisms and higher levels of distress (Compas, 2015). Individuals in this type of relationship can feel very alone and burdened in caring for their child with cancer—despite the fact that they have a partner—due to lack of communication or challenges sharing responsibilities related to their child’s illness. In an earlier report, we characterized these parents as “lone parents” based on their perception of feeling alone in their parenting and their self-reports of caring for an ill child largely on his or her own rather than in conjunction with a partner (Brown et al., 2008).

Distinguishing parenting in this manner allows for identification of individuals who are married/partnered yet perceive that they are very much alone when caring for a child with a serious illness. Feeling alone despite being married/partnered can be due to separation during hospitalizations, distance of hospitalization, family disruption or dysfunction, poor communication or cooperation within the parents’ relationship, and vastly different coping styles between partners. Lone parents may feel particularly torn between conflicting family responsibilities, especially when only one person is available to meet the financial and caregiving needs of the entire family (Brown et al., 2008; Crosier, Butterworth, & Rodgers, 2007; Rosenberg-Yunger et al., 2013). On the other hand, a parent can be demographically single but still have considerable support caring for an ill child from relatives, friends, or from a partner or significant other. Parents who considered themselves a lone parent when caring for their ill child have been found to have significantly greater distress than those who considered themselves to be married or partnered (Wiener et al., 2014).

A “think tank” at the National Institutes of Health was organized in 2007 to frame questions pertaining to the particular burdens of “lone” parents of children living with a chronic or life-limiting illness (Brown et al., 2008). The resulting Lone Parent Study Group, consisting of nationally recognized experts in psychosocial aspects of pediatric cancer, designed and conducted an exploratory multi-institutional study of parents of children diagnosed with cancer. Recommendations were made to examine health behaviors of parents, both lone and non-lone, following their child’s cancer diagnosis in order to better understand the mechanisms leading to adverse health outcomes for parents. In this current article, we report the results of our exploratory analyses of parental self-report of their own health behavior changes and changes in relationships and in spiritual faith during their child’s treatment. This study was part of a larger study of lone parents of children with cancer. Our aim for this study was to (1) identify parents who perceive themselves to be lone parents or non–lone parents in terms of feeling alone in caring for their child with cancer and (2) explore self-reported changes in health behavior, relationships, and spiritual faith before and after the child’s diagnosis.

Materials and Methods

Sample

Parents of children ages 1 to 18 years who were 6 to 18 months postcancer diagnosis and undergoing active treatment at 10 cancer centers from around the United States were invited to participate in this study. As parenting challenges can change at different points of the treatment trajectory, we chose 6 to 18 months postcancer diagnosis to avoid the initial crisis stage of a new diagnosis and to be able to include children currently in active treatment with the expectation that by 6 months postdiagnosis, parental caregiving patterns for the child’s treatment have generally become established. Relationship status of the parent participants was unknown prior to enrollment (not prescreened).

Procedure

At each collaborating institution, potential participants (those whose child was diagnosed with cancer between 6 and 18 months prior) were approached during routine clinic visits by a member of their treatment team (psychologist, social worker, nurse practitioner, or physician) or designated study personnel. Potential participants were asked if they would be interested in participating in a one time study designed to learn about the experiences of parents who are caring for a child with cancer. If interested, an investigator at the site reviewed the consent form with them. After signing the consent, each parent completed a Parenting Questionnaire (PQ), which was designed by the Lone Parent Study Group for this study.

Parents were consecutively enrolled at each site during a 9-month period of time during routine outpatient clinic visits. Completed deidentified questionnaires were sent back to the sponsoring site (National Institutes of Health) via FedEx for data entry and analyses. The centers, as previously reported (Wiener et al., 2014), covered major geographic areas in the United States (Table 1) and represented centers in both urban and rural settings. This study was initially approved by the institutional review board at the National Institute of Mental Health followed by institutional review board approval at the 9 other participating centers.

Table 1.

Collaborating Sites.

| Lone-Parent Study Group sponsoring site |

| National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD |

| National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD |

| Participating sites |

| Akron Children’s Hospital, Akron, OH |

| Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA |

| Miller Children’s Hospital, Long Beach, CA |

| Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY |

| Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK |

| St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN |

| University of Alabama, Birmingham, AL |

| University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS |

Measurements

Participation included a one-time paper-and-pencil completion of the PQ. The PQ was designed by members of the Lone Parent Study Group to capture differences between the experiences of demographically single and demographically partnered parents and differences between those who perceived themselves as being a lone parent when caring for their child with cancer (Brown et al., 2008) and those who did not. The questions were developed based on relevant professional literature and the clinical experience and expertise of the Lone Parent Study Group in this area. The interview questions and format were pretested at the coordinating site for face validity, understandability, and language comprehension level.

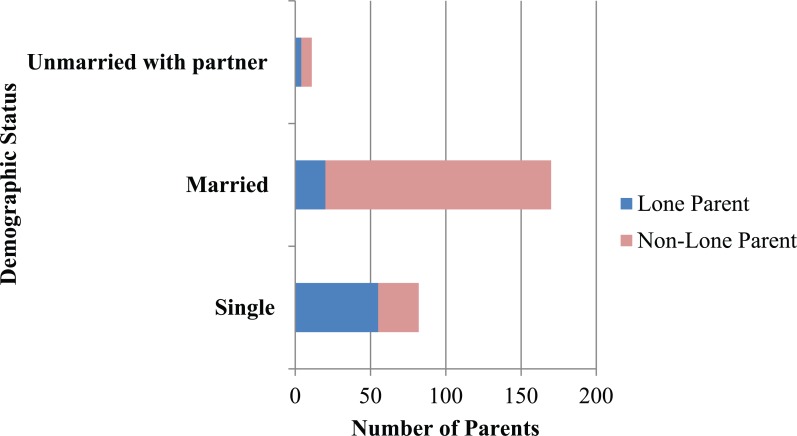

In addition to questions related to demographic factors, perceptions of support, distress, and perceived child needs, domains of the PQ include perceptions of available emotional, financial, logistical support, quality of relationships with their sick and healthy child(ren), relatives, friends and coworkers, caregiver physical and mental health functioning, and spiritual faith before and after the child’s diagnosis. Response categories were “gotten worse,” “stayed the same,” or “improved,” relative to the time of the child’s diagnosis (see Figure 1). Parents reported demographic information including child’s age, gender, family’s individual race, and family monthly income (<$1000 to >$10 000), and their marital status (see Table 2).

Figure 1.

Lone parent questionnaire items on changes in parental health behaviors, relationship quality, and spiritual faith since child’s cancer diagnosis.

Table 2.

Demographics.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender of parent | ||

| Female | 216 | 82.1 |

| Male | 45 | 17.1 |

| No response | 2 | 0.8 |

| Age of child (years) | ||

| 1-5 | 111 | 42.2 |

| 6-12 | 82 | 31.2 |

| 13-18 | 70 | 26.6 |

| Race | ||

| Caucasian | 176 | 66.9 |

| African American | 37 | 14.1 |

| Asian | 6 | 2.3 |

| Native Hawaiian/Alaskan | 3 | 1.1 |

| Mixed | 8 | 3.0 |

| Other | 19 | 7.2 |

| No response | 14 | 5.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 35 | 13.3 |

| Highest level of education | ||

| Less than high school | 27 | 10.2 |

| High school graduate | 58 | 22.1 |

| Some college | 91 | 34.6 |

| Bachelors | 44 | 16.7 |

| Graduate school | 42 | 16.0 |

| No response | 1 | 0.4 |

| Monthly income ($) | ||

| <1000 | 40 | 15.2 |

| 1000-1999 | 65 | 24.7 |

| 2000-3999 | 69 | 26.2 |

| 4000-5999 | 50 | 19.0 |

| 6000-7999 | 13 | 4.9 |

| 8000-9999 | 2 | 0.8 |

| >10 000 | 17 | 6.5 |

| No response | 7 | 2.7 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Single | 82 | 31.2 |

| Married | 170 | 64.6 |

| Unmarried, with partner | 11 | 4.2 |

| Changes in work status | ||

| No change | 87 | 33.1 |

| Work fewer hours | 57 | 21.7 |

| Work more hours | 11 | 4.2 |

| On leave from job, waiting | 25 | 9.5 |

| On leave | 16 | 6.1 |

| Quit Job | 29 | 11.0 |

| Fired | 6 | 2.3 |

| Other | 29 | 11.0 |

| No response | 3 | 1.1 |

| Financial concerns | ||

| No concerns | 16 | 6.1 |

| Some concerns | 150 | 57.0 |

| Lot of concerns | 92 | 35.0 |

| No response | 5 | 1.9 |

| Child’s current health | ||

| Excellent | 29 | 11.0 |

| Very good | 82 | 31.2 |

| Good | 120 | 45.6 |

| Not very good | 26 | 9.9 |

| Poor | 2 | 0.8 |

| No response | 4 | 1.5 |

Recognizing that typical demographic questions about marital status do not capture all relevant aspects of sharing or not sharing parental responsibilities for an ill child, we asked all parents to complete the following: (1) a demographic checklist identifying the individual as single, married, or unmarried but has a partner; and (2) “When it comes to caring for your child with cancer, do you feel like a single parent?” (with the response choices of “always,” “sometimes,” or “never”).

Statistical Analysis

For our first aim, to identify whether there were differences between parents who perceive themselves to be lone parents or non–lone parents, we combined responses of “sometimes” and “never” into the category of “non–lone parent,” and those who answered “always” are referred to as “lone parents.” We felt the statement of complete lack of support (“always”) represented a substantially stronger judgment of loneness, as “sometimes” feeling alone could reflect a normal or typical experience. Thus, a lone parent could be a parent who was demographically single, or demographically partnered (either married or unmarried but with a partner), but feeling alone in their caregiving role for their ill child.

To address our second aim, to explore self-reported changes in health behavior, relationships and spiritual faith since the child’s diagnosis, descriptive analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 21 (IBM, 2012). On the PQ, participants were asked to rate whether specific health behaviors, relationships, and their spiritual faith had “gotten worse,” “stayed the same,” or “improved” since their child’s diagnosis. Each of these was analyzed for the entire sample, and for the subgroups of lone parents, non–lone parents, demographically single, and demographically partnered parents. A χ2 analysis was used to compare health behaviors of lone parents to non–lone parents. A χ2 analysis was used to further explore other differences among reported health behavior by demographic subsample groups, including income level, parental race, age of the child, and type of child’s cancer. A significance level of .05 (2-tailed) was used for all analyses.

Results

Demographic Findings

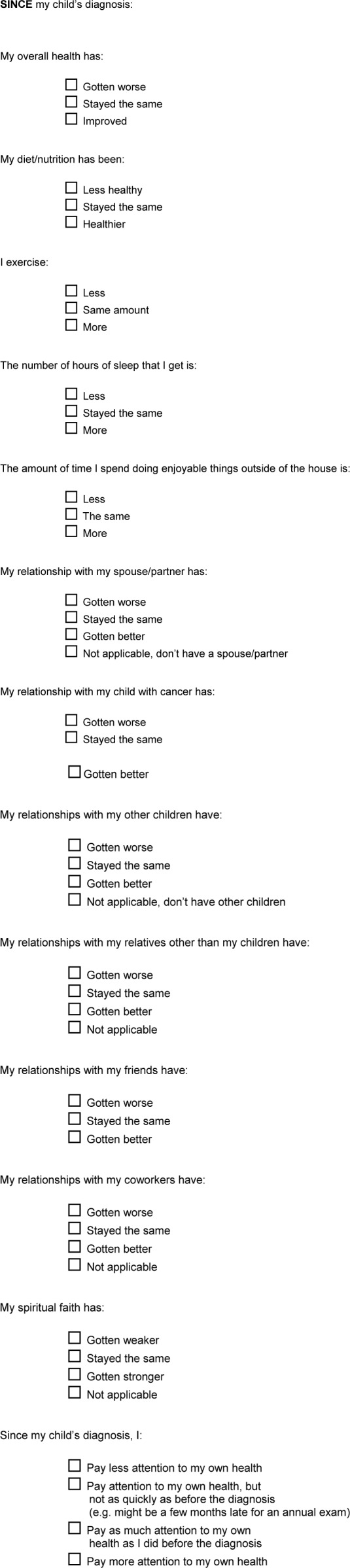

Two hundred and sixty-three parents of children currently undergoing cancer treatment participated. The sample was predominantly Caucasian (66.9%; N = 176). Approximately one third (31.2%; N = 82) of the sample identified themselves as demographically single. The other 170 parents (64.6%) identified themselves as married, with an additional 11 parents identified as unmarried with a partner (4.2%). Of the demographically single subsample, 67.0% (N = 55) reported feeling like a “lone” parent when it came to caring for their child with cancer. Of married parents, 11.8% (N = 20) reported feeling “lone” (Figure 2). Of those who are unmarried but have a partner, 36.4% (N = 4) reported feeling like a “lone” parent. Of the total group of 263 parents, 79 (30.0%) were designated as “lone” parents based on the self-report of feeling alone in caring for their child with cancer. Six participants did not answer the question about feeling like a “lone” parent when caring for their child with cancer and thus could not be classified as a lone or partnered parent. Additional demographic characteristics of the sample are in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Parents identifying as “lone” by demographic status.

Physical Health and Well-Being

Forty percent of all parents in the total sample, regardless of marital or parenting status, reported that their overall health had gotten worse after the child’s cancer diagnosis, with 61.6% (N = 162) reporting poorer diet/nutrition, 66.9% (N = 176) less exercise, 81.0% (N = 213) reduced sleep, and 82.9% (N = 218) less time doing enjoyable activities (P = <.001; Table 3). Half of the sample reported paying less attention to their own health (52.1%) after their child’s diagnosis. There were no significant differences between lone parents and non–lone parents or between demographically single parents and demographically partnered parents on self-reported physical health or well-being. Changes in parental health behaviors in the total sample were also not associated with the age of their child, parent race, or child’s type of cancer. Those with higher income were less likely to endorse reduced sleep (P = .004) and reduced exercise (P = .05). Mothers reported more lost sleep (P = .006) than fathers. The amount of time parents spent doing enjoyable activities outside of the house was reduced for both non–lone parents (83.1%; N = 148) and lone parents (84.8%; N = 67).

Table 3.

Reported Health Behaviors and “Do You Consider Yourself a Single Parent When Caring for Your Child With Cancer?”.

| Lone Parents (N = 79)a |

Partnered Parents (N = 178) |

P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gotten Worse, n (%) | Same, n (%) | Improved, n (%) | Gotten Worse, n (%) | Same, n (%) | Improved, n (%) | ||

| Overall health | 30 (38.5) | 45 (57.7) | 3 (3.8) | 72 (40.4) | 99 (55.6) | 7 (3.9) | >.05 |

| Diet/nutrition | 50 (64.1) | 22 (28.2) | 6 (7.7) | 109 (61.2) | 53 (29.8) | 16 (9.0) | >.05 |

| Exercise | 55 (69.6) | 20 (25.3) | 4 (5.1) | 119 (66.9) | 46 (25.8) | 13 (7.3) | >.05 |

| Hours of sleep | 65 (82.3) | 10 (12.2) | 4 (5.0) | 143 (80.8) | 29 (16.4) | 5 (2.8) | >.05 |

| Doing enjoyable things | 67 (84.8) | 9 (11.4) | 3 (3.8) | 148 (83.6) | 25 (14.1) | 4 (2.3) | >.05 |

| Relationship with child with cancer | 4 (5.1) | 26 (33.3) | 48 (61.5) | 4 (2.3) | 67 (38.1) | 105 (59.6) | >.05 |

| Relationship with other childrenb | 18 (30.0) | 24 (40.0) | 18 (30.0) | 24 (16.0) | 78 (52.0) | 48 (32.0) | <.02 |

| Relationship with relatives | 18 (23.3) | 36 (46.8) | 23 (29.9) | 24 (14.0) | 97 (56.4) | 51 (29.6) | >.05 |

| Relationship with friends | 25 (32.9) | 29 (38.2) | 22 (28.9) | 36 (20.5) | 102 (58.3) | 37 (21.1) | <.012 |

| Relationships with coworkers | 3 (8.1) | 26 (70.3) | 8 (21.6) | 11 (9.6) | 80 (70.1) | 23 (20.2) | >.05 |

| Spiritual faith | 9 (11.3) | 20 (25.3) | 50 (63.3) | 15 (8.8) | 42 (24.6) | 114 (66.7) | >.05 |

Note: The bold indicates the statistically significant difference.

Six parents did not answer the question.

Not all parents had other children.

Change in Relationship Quality

Two hundred and eleven parents in the total sample reported having more than one child. As shown in Table 3, significantly more lone parents (30.0%; N = 18) reported that the quality of their relationship with their other children had gotten worse since their child’s diagnosis. A lower percentage of non–lone parents (16.0%; N = 24) reported these relationships had worsened since the child’s diagnosis (P = .02). Additionally, more lone parents (32.9%; N = 25) than non–lone parents (20.5%; N = 36) reported that their relationships with friends had gotten worse after their child’s cancer diagnosis (P = .012). Relationships with their child with cancer improved in the majority of parents, both lone parents and non–lone parents.

Spiritual Faith

Spiritual faith was reported as improving since the child’s diagnosis for both lone parents (63.3%; N = 50) and non–lone parents (66.7%; N = 114). There were no significant differences between lone parents and non–lone parents in self-reported change in spiritual faith since the child’s cancer diagnosis.

Discussion

From a cohort that included parents from 10 hospital centers throughout the United States, this pilot study is the first to characterize a broad range of self-reported parental health and well-being changes following a child’s diagnosis with cancer. Our data indicate that, while parental overall health was retrospectively judged by the majority of parents to be stable (ie, the same as before the child’s diagnosis), worsening of specific health behaviors was reported for diet and nutrition, decreased physical activity, less sleep, and less time spent doing enjoyable activities across the total sample.

In this study, 30% of parents in our study reported feeling like a lone parent. This finding emphasizes the importance of asking about perceptions of social support rather than relying solely on assumptions based from demographic information. More research would be useful to understand the dynamics of families in which married spouses perceive themselves as “lone” parents in the hospital setting and in which those who are demographically single report feeling that they are not alone in caring for their ill child.

Additionally in our study, parents who perceived they were lone parents indicated that they experienced significant worsening of relationships with their friends and their other children compared with non–lone parents. Although speculative, this could be because lone parents have very limited time to spend with their other children or interact with friends when they have a sick child, as they may not have another adult to continue to monitor the ill child. It might also be a reflection of disappointment lone parents feel in friends due to their needs for multiple types of support when their child is ill. Considering that those coping with a child’s cancer on their own generally report a decline in relationship quality during this stressful time suggests interventions to improve relationship quality and social support for parents could be useful. This may be particularly true for those who perceive themselves to be lone parenting after their child’s diagnosis. Research focused on these areas would be important, as parents feel particularly distressed when they feel they are inadequately parenting one child to care for another. Without adequate social support, lone parents could easily feel overwhelmed and experience despair, which, in turn, could adversely affect the ill child.

What is notable about our data is that the majority of parents, both those caring singly or with support for their child with cancer, reported considerable reductions in specific positive health behaviors after their child’s diagnosis. These findings suggest that after a child is diagnosed with cancer, parents may be at risk for reduced self-care in the area of health behaviors. Hospitals might consider finding ways to support parents in seeking exercise by providing respite care for hospitalized children, access to treadmills or exercise bikes, offering healthier food in hospital cafeterias, giving parents maps of walking or running paths in the area, providing yoga or other exercise classes for parents and encouraging nurses to recommend that parents take time for exercise.

Consistent with earlier research (Silver, Westbrook, & Stein, 1998), demographic differences (age and gender) had little overall impact on parental self-care behaviors among parents of children diagnosed with chronic conditions. In our study, income was related to parental sleep and exercise. These findings appear in keeping with findings from Mullins et al. (2011), who found socioeconomic status mediated the relationship between single parent status and parenting stress.

Our results indicate that spiritual faith increased in over half of our cohort since the time of their child’s diagnosis, with no differences found between lone parents and non–lone parents. Again, while speculative, these data suggest that spiritual services in pediatric oncology programs may be helpful to parents regardless of whether they have other forms of support. Parents facing a child’s serious, life-threatening illness and possible death who are trying to make sense of illness and suffering often look beyond the material world for comfort and explanations (Purow, Alisanski, Putnam, & Ruderman, 2011). The results of a qualitative study with parents of children receiving palliative care demonstrated that religion, spirituality, or life philosophy played diverse and important roles in the lives of most parents (Hexem, Mollen, Carroll, Lanctot, & Feudtner, 2011).

Surprisingly, few differences were noted between our lone parents and non–lone parents in self-care, change in relationship quality, and spiritual faith. We believe our approach of characterizing parents not only on self-reported marital status but also on self-perception of feeling like a lone parent in caring for their ill child regardless of marital status might illuminate additional felt burdens and lead to different possible interventions. We had expected lone parents might report greater problems in caring for themselves when their child was undergoing treatment for cancer, but our data did not show such differences. This begs the double question of why non–lone parents did not fare better, and why lone parents did not fare worse. Clearly, parents’ ability to care for themselves and to interact with others is a function of a more complex mix of factors. There could be compensatory factors associated with a lone parent’s situation. For example, perhaps there is some ease or simplicity in making decisions without a need to consult a partner or to argue about different views or approaches. Or, perhaps the lone parent’s need to go to work also provides opportunities to take a break from the hospital routine, have positive interactions with colleagues, and perhaps even eat better than in the hospital setting. We may have insufficiently considered other important factors in our analysis, such as the child’s current health status and its impact on parental health behaviors or interactions with others for both lone parents and non–lone parents. Lone parents did report greater declines in their relationships with their other children and friends than did non–lone parents, at a point when they were facing many additional burdens. This could be due to having less time, physical fatigue. or reduced emotional energy to invest in relationships. Future research in maintaining parental social support may clarify why these differences were found.

There are several important limitations of the study to note. First, content and construct validity and reliability data are not yet available for the PQ. A second limitation is the cross-sectional design. Duration of caregiving and chronicity of stress are known to worsen health (Epel et al., 2004), which highlights the need for longitudinal studies. Third, we only looked at parents whose child was 6 to 18 months post their cancer diagnosis, which does not encompass the initial, high-stress period around the diagnosis or the transition off treatment, which has also been shown to be particularly stressful for parents (Duffey-Lind et al., 2006). Fourth, reduction in health behaviors is only assessed by self-report; we have no objective indicators of parental health. Fifth, two thirds of our sample were Caucasian; subgroups were not large enough to determine what cultural differences there may be in the impact of being a “lone” parent.

Future parental caregiver health outcomes research should be longitudinal, with differentiation of the health status and diagnosis of the child, focusing on more diverse medical conditions and cohorts with objective versus perceived measures of parental health and health behaviors over the trajectory of a child’s illness. Such research could help delineate those subsets of parents who are most at risk in terms of their own health outcomes.

Implications for Nurses

Nurses often directly observe the impact a child’s cancer has on parental health behaviors, particularly parents who appear to be parenting the child on their own, with limited support outside the hospital setting. Nurses may be ideal candidates to deliver supportive interventions to improve parental self-care as they have the opportunity to have multiple conversations with parents about how they are addressing their own self-care needs. Indeed, our data suggest that ongoing assessment of parental self-care may be in order throughout the course of the child’s treatment regimen. Direct nursing care strategies may be employed to help parents develop and implement goals to improve how they care for themselves during their child’s treatment while continuing to feel they are a “good enough” parent (Foster, LaFond, Reggio, & Hinds, 2013).

Nurses are excellent “gatekeepers” for other services. When it seems clear that additional services would be useful, nurses are in a position to refer the parent to social work, nutrition, support groups, and other resources where they can obtain additional advice about how to balance staying healthy while stressed. It would also be helpful for nurses to be aware of some of the many online resources, such as “wecare.ca” that highlight tips on how to take care of oneself during an intense caregiving time.

It is important that when nurses identify or learn of a behavior in a parent that might have negative health consequences, such as decreased physical activity, they work with the parent and with resources available in the medical center to find ways to help get “coverage” so the parent can get some rest, go to the gym or to an exercise class, visit a chapel, or go for a walk. Many parents may be reluctant to take time away from their child, and as such, will need encouragement to do so.

Conclusions

The significant psychosocial impact of a diagnosis of childhood cancer on the parents over the course of treatment is profound, well established, and widely understood. Our data add to this understanding by suggesting that after a child is diagnosed with cancer, both lone parents and non–lone parents experience negative changes in their health behaviors, including poorer diet and nutrition, decreased physical activity, less sleep, and less time spent doing enjoyable activities. More non–lone parents found that support from friends increased or stayed the same after their child’s diagnosis, whereas a higher proportion of lone parents reported deteriorating quality of relationships with friends. Spiritual faith increased for all groups of parents.

Assessment of the psychosocial needs of the family is the first action necessary to determine subsequent steps for delivering interventions that address the psychosocial needs for families throughout the treatment trajectory (Kazak et al., 2015). As both self-care and caregiving stress are strongly linked to health outcomes, stress reduction and behavioral health interventions designed to help mitigate the negative effects of caregiving may improve the psychosocial and physical well-being of all parents of children with cancer. Additionally, it may be useful to consider more in depth the impact of lone parenting over time, in order to target parents most in need of support at the points in time when they can make the best use of professional interventions. In this regard, additional research is certainly warranted to better determine the relationship between parental self-care and long-term outcomes in parents of children with cancer.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support and study contributions of our additional Lone Parent Study Group colleagues: Mary Jo Kupst, PhD; Sarah Friebert, MD; Avi Madan Swain, PhD; David Elkin, PhD; and Sean Phipps, PhD.

Author Biographies

Lori Wiener, PhD, is Co-Chair of the Behavioral Science Core and Head of the Psychosocial Support and Research Program in the Center for Cancer Research, Pediatric Oncology branch. Her clinical research has focused on the needs of critically ill children and their families, adaptation, and psychosocial interventions.

Adrienne Viola, BS, holds an MA in public health and is in a joint MD/PhD program at Robert Wood Johnson School of Medicine. She has a strong interest in health behaviors and epidemiology.

Julia Kearney, MD, is a pediatric psycho-oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Her collaborative clinical research focuses on pediatric delirium, communication skills training in pediatric oncology, and psychosocial interventions.

Larry L. Mullins, PhD, is the Vaughn O. Vennerberg Professor of Psychology in the Department of Psychology and is Associate Dean for Research in the College of Arts and Sciences at Oklahoma State University. He is particularly interested in identifying risk factors for families of youth with chronic health problems and developing clinical interventions that promote resilience.

Sandra Sherman-Bien, PhD, holds a doctorate in clinical psychology from the San Diego State University/University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program, and conducted this research while at the Jonathan Jaques Children’s Cancer Center, Miller Children’s Hospital, Long Beach, California. Her research has focused on health-related quality of life of pediatric patients and their families including the role of the hospital environment.

Sima Zadeh, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist and research fellow in the Pediatric Oncology branch of the National Cancer Institute. Her research focuses on the psychosocial needs of medically ill children and their families.

Andrea Farkas-Patenaude, PhD, is the director of Psychology Research and Clinical Services at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and associate professor of psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Much of her work has focused on the psychosocial burdens affecting children with cancer and their family members.

Maryland Pao, MD, is the clinical director and chief of the Psychiatric Consultation Liaison Service at NIH Clinical Center. Her research interests are in the coping and adaptation of children with chronic illness.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported [in part] by the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of Mental Health intramural programs of the National Institutes of Health. This funding supported the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the article; and the decision to submit the article for publication. The Andre Sobel River of Life Foundation contributed the gift cards for the study participants.

References

- Bennett Murphy L. M., Flowers S., McNamara K. A., Young-Saleme T. (2008). Fathers of children with cancer: Involvement, coping, and adjustment. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 22, 182–189. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2007.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R. T., Wiener L., Kupst M. J., Brennan T., Behrman R., Compas B. E., . . . Zeltzer L. (2008). Single parenting and children with chronic illness: An understudied phenomenon. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 33, 408-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compass B.E., Bemis H, Gerhardt C.A., Dunn M.J., Rodriquez R.M., Desjardins L., Preacer K.J., Manring S., Vannatta K. Mothers and fathers coping with their children’s cancer: Individual and interpersonal processes. Health Psychology, 34(8), 783-93, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosier T., Butterworth P., Rodgers B. (2007). Mental health problems among single and partnered mothers: The role of financial hardship and social support. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 42, 6-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell M. L., Grossoehme D. H. (2015). Spiritual and religious considerations. In Wiener L., Pao M., Kazak A. E., Kupst M. J., Patenaude A. F., Arceci R. (Eds.), Pediatric psycho-oncology: A quick reference on the psychosocial dimensions of cancer symptom management (2nd ed., pp. 281-290). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duffey-Lind E. C., O’Holleran E., Healey M., Vettese M., Diller L., Park E. R. (2006). Transitioning to survivorship: A pilot study. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 23, 335-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis-Durstine K., Brown M. (in press). Spiritual care in pediatric oncology. In Abrams A., Muriel A., Wiener L. (Eds.), Pediatric psychosocial oncology: Textbook for multi-disciplinary care. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Epel E. S., Blackburn E. H., Lin J., Dhabhar F. E., Morrow J. D., Cawthon R. M. (2004). Accelerated telomere shortening in response to life stress. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 101, 17312-17315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster T. L., LaFond D. A., Reggio C., Hinds P. S. (2010). Pediatric palliative care in childhood cancer nursing: From diagnosis to cure or end of life. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 26, 205-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greening L., Stoppelbein L. (2007). Brief report: Pediatric cancer, parental coping style, and risk for depressive, posttraumatic stress, and anxiety symptoms. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 32, 1272–1277. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hexem K. R., Mollen C. J., Carroll K., Lanctot D. A., Feudtner C. (2011). How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 14, 39-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp [Google Scholar]

- Kazak A. E., Abrams A. N., Banks J., Christofferson J., DiDonato S., Grootenhuis M. A., . . . Kupst M. J. (2015). Psychosocial assessment as a standard of care in pediatric cancer. Pediatric Blood & Cancer, 62, S426-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney J. A., Salley C. G., Muriel A. C. (in press). Psychosocial support for parents of children with cancer as a standard of care in pediatric oncology. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- Klassen A. F., Klaassen R., Dix D., Pritchard S., Yanofsky R., O’Donnell M., . . . Sung L. (2008). Impact of caring for a child with cancer on parents’ health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 5884-5889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice-Stam H., Oort F. J., Last B. F., Grootenhuis M. A. (2008). Emotional functioning of parents of children with cancer: The first five years of continuous remission after the end of treatment. Psycho- Oncology, 17, 448–459. 10.1002/pon.1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoone J. K., Wakefield C. E., Yoong S. L., Cohn R. J. (2013). Parental sleep experiences on the pediatric oncology ward. Supportive Care in Cancer, 21, 557-564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins L. L., Wolfe-Christensen C., Chaney J. M., Elkin T. D., Wiener L., Hullmann S. E., Junghans A. (2011). The relationship between single parent status and parenting capacities in mothers of youth with chronic health conditions: The mediating role of income. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 36, 249-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purow B., Alisanski S., Putnam G., Ruderman M. (2011). Spirituality and pediatric cancer. Southern Medical Journal, 104, 299-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabineau K. M., Mabe A., Vega R. A. (2008). Parenting stress in pediatric oncology populations. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 30, 358-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg-Yunger Z. R. S., Granek L., Sung L., Klaassen R., Dix D., Cairney J., Klassen A. F. (2013). Single-parent caregivers of children with cancer: Factors assisting with caregiving strains. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 20, 45-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver E. J., Westbrook L. E., Stein R. E. K. (1998). Relationship of parental psychological distress to consequences of chronic health conditions in children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 23, 5-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield C. E., McLoone J. K., Evans N. T., Ellis S. J., Cohn R. J. (2014). It’s more than dollars and cents: The impact of childhood cancer on parents’ occupational and financial health. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 32, 602-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener L., Pao M., Battles H., Zadeh S., Patenaude A., Madan-Swain A., . . . Kupst M. J. (2014). Socio-environmental factors associated with lone parenting chronically ill children. Child Health Care, 42, 265-280. [Google Scholar]