Abstract

When dreaming during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, we can perform complex motor behaviors while remaining motionless. How the motor cortex behaves during this state remains unknown. Here, using intracerebral electrodes sampling the human motor cortex in pharmacoresistant epileptic patients, we report a pattern of electroencephalographic activation during REM sleep similar to that observed during the performance of a voluntary movement during wakefulness. This pattern is present during phasic REM sleep but not during tonic REM sleep, the latter resembling relaxed wakefulness. This finding may help clarify certain phenomenological aspects observed in REM sleep behavior disorder. Ann Neurol 2016;79:326–330

Dreams are frequently reported by subjects awakened from rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.1, 2 In our dreams, we can move and perform various complex motor behaviors while being completely motionless due to an atonia of postural muscles.3 How the human motor cortex (Mc) behaves during this state from an electrophysiological point of view remains unknown. Clinical observations in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), a disease characterized by episodes of vigorous dream‐enacting behaviors due to a dysfunction of brainstem nuclei and subsequent loss of muscular atonia during REM sleep,4 suggest a direct activation of the Mc during REM sleep.5 Moreover, RBD‐associated behaviors are reported to occur more frequently during phasic REM sleep (where bursts of REMs occur) than during tonic REM sleep (where REM sleep occurs without actual REMs),6, 7 suggesting a higher level of activation of the Mc during phasic REM sleep.

To evaluate the presence of different patterns of Mc activation during REM sleep, we analyzed the overnight intracerebral sleep stereo‐electroencephalographic (S‐EEG) activity of the primary Mc in 7 patients with drug‐resistant epilepsy undergoing presurgical assessment. We compared the mean S‐EEG power spectrum of the Mc during phasic and tonic REM sleep as well as in voluntary movement during wakefulness.

Subjects and Methods

Patients and Data Recording

Intracerebral S‐EEG data were recorded from 7 patients (5 males, 2 females; mean age = 28.0 ± 7.1 years) with drug‐resistant focal epilepsy who underwent S‐EEG during a presurgical evaluation.8 Informed written consent was obtained from all patients in accordance with the hospital's ethical committee policy (Niguarda Cà Granda Hospital, Milan, Italy). Patients included in this study shared the presence of electrode contact pairs unequivocally localized within the Mc and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFc; for further details, see Nobili et al9. The dlPFc was chosen because previous studies have shown that this region is representative of scalp sleep EEG dynamics across the night.9 No patients reported any history of sleep disorder.

The activity recorded from Mc and dlPFc was free of ictal and interictal epileptic discharges. Two bipolar derivations between adjacent electrode contacts, localized within the paracentral lobule (leg motor area) and the dlPFc respectively, were considered. Electrophysiological activities acquired during both sleep and waking recording sessions included scalp EEG (Fz and Cz), bilateral electro‐ocular activity (EOG), and submental electromyographic activity (EMG). Electrophysiologic signals were digitally recorded with a minimum sampling rate of 512Hz following antialiasing analog filtering. Both intracerebral and scalp EEG signals were digitally filtered in the 0.2 to 70Hz passband, whereas EOG was 0.2 to 15Hz bandpass filtered and EMG was 5 to 150Hz bandpass filtered.

Sleep Scoring and Analysis of REM Sleep

Polysomnographic recordings were scored as 30‐second epochs.10 REM sleep was subdivided into phasic or tonic REM sleep. Phasic REM sleep epochs were selected on the basis of the presence of at least 3 REMs. Tonic REM sleep epochs were scored when they did not contain any eye movement but the EEG continued to show low‐amplitude, mixed‐frequency activity without K‐complexes or sleep spindles and the chin EMG tone remained low.10 Clear sequences of REMs, preceded by at least 10 seconds of silent EOG activity, were marked for further analysis (see below).

Analysis of Wakefulness States

Electrophysiological data were also acquired during wakefulness. While patients were resting, with eyes closed and lying on their back, they were requested to raise the leg corresponding to the motor area sampled with intracerebral electrodes. The onset of the movement was marked in the recording and selected for further analyses.

Spectral Analysis

Spectral analysis by Fourier transform (Welch method, Tukey window, 4‐second overlapping artifact‐free intervals) was performed to: (1) estimate the spectral distribution of EEG power for each 30‐second epoch of tonic and phasic REM sleep, (2) characterize the 8‐second epochs immediately preceding and following the onset of REM sequences during phasic REM sleep, and (3) characterize the 8‐second epochs immediately preceding and following the onset of leg movements during wakefulness. Due to the absence of artifacts in intracerebral recorded data, we could also perform spectral analysis of the intervals containing ocular movements.

Statistical Analysis

Mc and dlPFc mean spectra were computed in each subject for phasic and tonic REM sleep. Mc mean spectra were also computed for the epochs preceding and following the onset of selected REMs and for the epochs preceding and following the onset of voluntary leg movements in wakefulness.

To verify the presence of frequency shifts in a large band (6–70Hz), each mean spectrum was characterized by its power‐weighted mean frequency,11 computed as:

where p i is the power density at the frequency f i and the mean frequency f m can be viewed as the barycenter of the frequency distribution. The effect of stage (phasic or tonic REM sleep) and region (Mc or dlPFc) was evaluated by a repeated measures analysis of variance followed by post hoc comparisons with Tukey adjustment. The same analysis was applied to evaluate spectral frequency changes associated with voluntary movements, by comparing the 8‐second intervals preceding and following movement onset.

To verify whether differences in mean frequency between phasic and tonic REM sleep could be directly associated with ocular movements, mean frequency values associated with the 8‐second intervals preceding and following the onset of REM sequences were compared by paired t test.

The significance threshold was set at 0.01. Statistical analyses were performed by means of the software package STATISTICA (version 10, StatSoft, www.statsoft.com).

Results

Activity of the Mc during Sleep

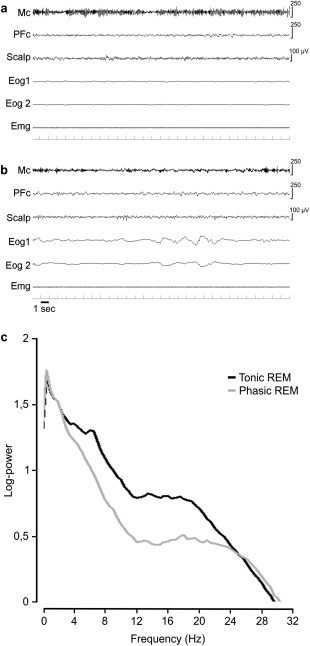

Figure 1A and B contain examples of a tonic and a phasic REM 30‐second epoch of the Mc in 1 subject. For each patient, a mean number of 72.14 (±19.01, standard deviation [SD]) epochs of tonic REM sleep and of 82.14 (±49.78, SD) epochs of phasic REM sleep were analyzed. Mean frequency spectral values were influenced by the phasic or tonic state of REM sleep (F 1,6 = 28.66, p < 0.002) but not by cortical topography (Mc vs dlPFc: F 1,6 = 0.094, not significant [NS]). However, an interaction between REM sleep state and cortical region was observed (F 1,6 = 28.30, p < 0.002). Post hoc comparisons showed that only the Mc presented higher mean frequency spectral values during phasic REM sleep when compared to tonic REM sleep (see Fig 1; Mc phasic: 20.45 ± 0.73Hz vs Mc tonic: 17.78 ± 0.47Hz, p < 0.002; dlPFc phasic: 19.56 ± 0.40Hz vs dlPFc tonic: 19.08 ± 0.46Hz, NS; mean ± standard error).

Figure 1.

Example of tonic (A) and phasic (B) rapid eye movement (REM) 30‐second epochs. Each epoch shows 3 electroencephalographic (EEG) derivations: 2 electro‐oculographic (Eog) traces and 1 chin electromyographic (Emg) trace. (C) Mean EEG spectra of motor cortex (Mc) activity during tonic and phasic REM sleep. Notice the EEG desynchronization, characterized by the disappearance of the mu‐rhythm (alpha‐like oscillatory activity) during phasic REM sleep (B), reflected in C by a decrease of power in a large frequency band up to 25Hz, with a slight increase of power above 25Hz. PFc = dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

The comparison between the mean frequency values of Mc activity associated with the (8‐second) epochs preceding (Mcpre) and following (Mcpost) the onset of ocular movements did not show any significant difference (Mcpre: 19.98 ± 0.86Hz, Mcpost: 20.89 ± 1.08Hz; paired t test = 1.58, df = 6, NS; mean ± standard error).

Activity of the Mc during Wakefulness

For each patient we analyzed at least 2 leg movements (range = 2–10).

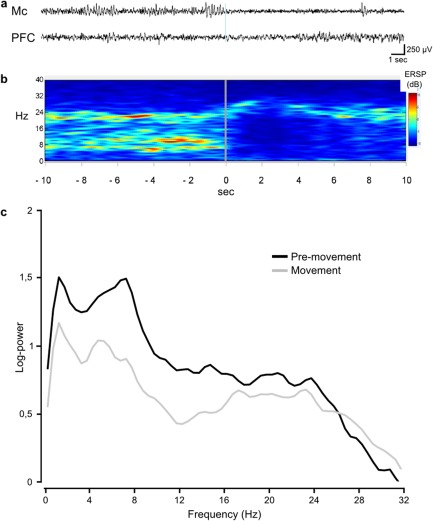

A clear mu‐rhythm (6–12Hz) characterized the activity of the Mc during the premovement epoch and disappeared at movement onset, followed by a predominant shift toward higher‐frequency beta activity (Fig 2A).

Figure 2.

Example of electroencephalographic (EEG) activity in the motor cortex (Mc) and in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC) during rest and voluntary limb movements. (A) EEG trace derived from a bipolar derivation in the Mc and PFC during a 20‐second epoch around the onset of a voluntary leg movement (marked by the gray vertical bar). Notice the EEG desynchronization, characterized by the disappearance of the mu‐rhythm (alpha‐like oscillatory activity) after movement in the Mc. (B) Time–frequency distribution of the amplitude of the EEG signal recorded from the Mc derivation and averaged among four 20‐second epochs centered around leg movements. (C) Mean EEG spectra in the Mc showing a decrease of power in a large frequency band up to 25Hz and with a slight increase of power above 25Hz, during leg movement. ERSP = event‐related spectral power.

Mean frequency was significantly affected by condition (before or after movement onset: F 1,6 = 63.55, p < 0.001) and was not significantly different between regions (Mc vs dlPFc: F 1,6 = 0.41, NS), but the region × condition interaction was significant (F 1,6 = 40.62, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons showed that only the Mc presented significant changes between conditions (see Fig 2; Mc after movement: 20.81 ± 0.87Hz vs Mc before movement: 17.96 ± 0.81Hz, p < 0.001; dlPFc after movement: 19.18 ± 0.78Hz vs dlPFc before movement: 18.57 ± 0.55Hz, NS; mean ± standard error).

Discussion

It has been shown that, in contrast to rest condition, motor execution is characterized by a desynchronization of EEG activity as revealed by a disappearance of the typical mu‐rhythm and by a decrease in power of alpha and beta EEG frequency bands.12 Here we show that during phasic REM sleep the human Mc exhibits an EEG pattern similar to the one observed when the Mc is activated (ie, when performing a voluntary movement). Conversely, tonic REM sleep is characterized by the presence of a mu‐rhythm and by EEG spectral values similar to those observed during relaxed wakefulness (see Figs 1 and 2). Phasic REM sleep is characterized by higher EEG frequency values with respect to tonic REM sleep. These results are in accordance with animal studies showing an activation of sensorimotor regions during REM sleep,13 with higher frequencies in phasic REM sleep compared to tonic REM sleep.14

It has been observed that active dreams are more frequently reported by patients after an awakening from phasic REM sleep than after tonic REM sleep15, 16; our observations could represent the electrophysiological correlate of this finding. Although we did not collect dream reports in our patients, we can hypothesize a pattern of Mc activation occurring during dreamed movements, similar to the pattern observed during active wakefulness. Such an interpretation is in line with a functional magnetic resonance imaging and near‐infrared spectroscopy study in lucid dreamers showing that a predefined motor task performed during dreaming elicits a neuronal activation in the sensorimotor cortex that largely overlaps with the one observed during motor execution.17 Interestingly, a recent electrophysiological intracerebral study in humans showed that REMs in REM sleep are associated with visual‐like activity, as during wakefulness.18

From a clinical point of view, our results are also in accordance with a higher frequency of RBD manifestations during phasic than during tonic REM sleep,6, 7 in agreement with the current hypothesis that dream‐enacted behaviors occurring during REM sleep are correlated with a direct activation of the cortical sensorimotor system.5, 16, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23 Lastly, we did not find significant differences in the mean frequency values of EEG Mc activity when comparing the 8 seconds before and following the onset of ocular movements. This suggests that the activation of the Mc of the paracentral lobule (located far from the frontal eye field) is not related to the ocular movements per se, but seems to reflect a widespread involvement of the sensorimotor system during dream‐related behaviors. Such a finding could help explain why sporadic RBD episodes may also occur without concomitant REMs.

Although technically challenging, future S‐EEG studies could further assess the relationship between dream content and the activity of more extensive cortical regions.

Author Contributions

F.D.C., L.N., M.F., and L.D.G. designed the study. G.L.R. performed the S‐EEG recordings. P.P., E.M., I.S., and G.L.R. collected the data. F.D.C., E.M., and S.A.G. conducted data analysis. F.D.C., L.N., P.P., S.A.G., M.F., and L.D.G. wrote the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Potential Conflicts of Interest

Nothing to report.

Acknowledgment

Supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (Targeted Research Grant RF‐2010‐2319316; L.N., P.P.), “Ministero della Salute” (Italian Ministry of Health) Targeted Research Grant RF‐2009‐1528677 (M.F. and L.D.G.) and the Quebec Health Research Fund (S.A.G.).

References

- 1. Dement W, Wolpert EA. The relation of eye movements, body motility, and external stimuli to dream content. J Exp Psychol 1958;55:543–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siclari F, Larocque JJ, Postle BR, Tononi G. Assessing sleep consciousness within subjects using a serial awakening paradigm. Front Psychol 2013;4:542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brown RE, Basheer R, McKenna JT, et al. Control of sleep and wakefulness. Physiol Rev 2012;92:1087–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schenk CH, Mahowald MW. REM sleep behavior disorder: clinical, developmental, and neuroscience perspectives 16 years after its formal identification in SLEEP. Sleep 2002;25:120–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Peever J, Luppi P‐H, Montplaisir J. Breakdown in REM sleep circuitry underlies REM sleep behavior disorder. Trends Neurosci 2014;37:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Manni R, Terzaghi M, Glorioso M. Motor‐behavioral episodes in REM sleep behavior disorder and phasic events during REM sleep. Sleep 2009;32:241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, et al. The relation between abnormal behaviors and REM sleep microstructure in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med 2009;10:174–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cardinale F, Cossu M, Castana L, et al. Stereoelectroencephalography: surgical methodology, safety, and stereotactic application accuracy in 500 procedures. Neurosurgery 2013;72:353–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nobili L, Ferrara M, Moroni F, et al. Dissociated wake‐like and sleep‐like electro‐cortical activity during sleep. Neuroimage 2011;58:612–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iber C, Ancoli‐Israel S, Chesson AL Jr, Quan SF. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events: rules, terminology and technical specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zarjam P, Epps J, Chen F. Spectral EEG features for evaluating cognitive load. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011;2011:3841‐3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pineda JA. The functional significance of mu rhythms: translating “seeing” and “hearing” into “doing.” Brain Res Rev 2005;50:57‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jackson A, Mavoori J, Fetz EE. Correlations between the same motor cortex cells and arm muscles during a trained task, free behavior, and natural sleep in the macaque monkey. J Neurophysiol 2007;97:360–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brankačk J, Scheffzük C, Kukushka VI, et al. Distinct features of fast oscillations in phasic and tonic rapid eye movement sleep. J Sleep Res 2012;21:630–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berger RJ, Oswald I. Eye movements during active and passive dreams. Science 1962;137:601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Arnulf I. The “scanning hypothesis” of rapid eye movements during REM sleep: a review of the evidence. Arch Ital Biol 2011;149:367–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dresler M, Koch SP, Wehrle R, et al. Dreamed movement elicits activation in the sensorimotor cortex. Curr Biol 2011;21:1833–1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Andrillon T, Nir Y, Cirelli C, et al. Single‐neuron activity and eye movements during human REM sleep and awake vision. Nat Commun 2015;6:7884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. De Cock VC, Vidailhet M, Leu S, et al. Restoration of normal motor control in Parkinson's disease during REM sleep. Brain 2007;130:450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dauvilliers Y, Boudousq V, Lopez R, et al. Increased perfusion in supplementary motor area during a REM sleep behaviour episode. Sleep Med 2011;12:531–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mayer G, Bitterlich M, Kuwert T, et al. Ictal SPECT in patients with rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Brain 2015;138:1263–1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luppi PH, Clément O, Valencia Garcia S, et al. New aspects in the pathophysiology of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: the potential role of glutamate, gamma‐aminobutyric acid, and glycine. Sleep Med 2013;14:714–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dauvilliers Y, Peigneux P. Ictal SPECT in patients with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Brain 2015;138(pt 11):e390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]