Abstract

Aim

We quantitatively analysed the effect of a course in communication on the content of nurse–parent encounters and the ability of nurses to respond to the empathic needs of parents in a level III neonatal intensive care unit.

Methods

We evaluated 36 and 45 nurse–parent encounters audio recorded before and after 13 neonatal nurses attended a communication course. The number of empathic opportunities, the nurses' responses to these and the ways they involved parents in their infants' care were studied.

Results

Both before and after the course, the nurses talked more than the parents during the conversations. This nurse‐centredness decreased after the course. The use of empathic or exploring responses to empathic opportunities increased from 19.9 ± 9.0% to 53.8 ± 8.9% (p = 0.027), whereas ignoring the feelings of the parents or giving inadequate advice decreased from 63.0 ± 10.0% to 27.5 ± 8.4% (p = 0.043) after the course. Use of statements expressing caring for the parents and encouragement for parents to participate in the care of their infant increased after the course (p = 0.0034 and p = 0.043, respectively). The nurses felt the course was very useful for their profession.

Conclusion

A course in communication techniques improved nurses' ability to respond to parents' feelings with empathy.

Keywords: Communication skills, Neonatal intensive care, Neonatal nursing, Newborn, Training

Abbreviations

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Key notes.

In this study, a novel method was used for quantitative analysis of the content of nurse–parent conversations.

A course in communication skills improved the ability of neonatal nurses to respond to parents' feelings with empathy and made them more attentive to parents' well‐being.

The nurses felt the course was very useful for their daily work and increased their confidence in communicating with parents.

Introduction

The illness and hospitalisation of a newborn infant are extremely distressing for the parents. Worry and uncertainty about the outcome and their inability to take care of the infant themselves, as well as the high‐tech environment of the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), arouse feelings of powerlessness in parents 1, 2. It is necessary for parents to obtain information about their infant's clinical situation and progress and learn to take care of their baby. Communication with healthcare providers is therefore essential for the parents during their child's hospitalisation. Research about the content and orientation of nurse–parent communication in the NICU is limited.

Parents' emotional needs are high in the NICU. Most parents exhibit elements of a grief response, such as numbness, anger, resignation and a search for meaning 2. A sudden deterioration or unpredictable alteration in the medical condition of the infant acutely increases parents' need for emotional support. In addition to being an important source of information, nurses can also give emotional support to the parents 3. Not surprisingly, the relationship parents have with the nurses caring for their infant is a significant factor affecting their satisfaction with their NICU experience 4. By responding to the feelings of parents with understanding and empathy, caregivers can help the parents cope with their situation. However, interacting with parents in distress and handling emotional reactions such as disbelief, disappointment, recriminations and anger is both stressful and demanding. In general, NICU nurses lack specific training in communication skills. In addition, there is a paucity of information on the ability of nurses to recognise and respond to emotions expressed by parents.

Although paediatric patients and their parents emphasise the importance of empathy during consultations 5, studies addressing the ability of caregivers to identify and respond to parents' emotions in the paediatric setting are lacking. Studies on adult patients have shown that physicians and other medical staff rarely respond with empathy to the feelings of their patients. In two studies on cancer patients, oncologists were found to respond empathically to only 10–22% of empathic opportunities, defined as negative emotions expressed by patients 6, 7. In another study, oncology physician assistants, nurse practitioners and nurse clinicians responded to patients' emotions with empathic language 30% of the time 8. Similarly, physicians responded to empathic opportunities during routine primary care and surgery office visits in 15–21% of primary care cases and in 38% of surgical cases 9, 10.

Communication can be considered a key clinical skill 11. It has been shown that communication problems are not resolved by time or clinical experience 12. Inadequate training in communication skills is a major factor contributing to high rates of burnout and psychological morbidity among oncologists 12. Training courses in communication techniques can significantly improve the communication skills of healthcare providers and their ability to respond empathically to patients' expressions of negative emotions 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies on communication skills training in neonatology.

We studied whether an interactive course in communication skills that allowed neonatal nurses to practice handling difficult communication situations in the NICU influenced the content of nurse–parent interactions and the ability of the nurses to respond to the empathic needs of parents.

Materials and methods

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee for Human Studies at Gothenburg University, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Setting

The study was conducted at the level III NICU of a university hospital that treats about 1000 newborns per year, including extremely premature and critically ill infants transported from other hospitals in the region. The unit has 22 beds divided into two intensive care rooms and two intermediate care rooms and a staff of about 120 doctors and nurses. It has a high turnover of patients, often leading to a high workload for doctors and nurses.

Course in communication skills

The communication course consisted of a two‐hour interactive lecture and one‐day practical workshop. The lecture consisted of an overview of the communication needs of NICU parents and basic information about important communication skills in various clinical settings, as well as of the importance of involving parents in the care of their infants, giving parents emotional support, identifying parents' emotions and responding to them with empathy.

The workshop consisted of small group discussions with three to four nurses and two facilitators (EH, HLK or KB). At the beginning of the workshop, the participants watched and discussed a few examples of video recorded communication situations based on adult case scenarios from Communication Skills in Clinical Practice (Health Education and Training Inc., Toronto, Ontario, Canada). The main part of the workshop consisted of discussing and practicing 16 difficult communication scenarios in the NICU that were based on real cases experienced or witnessed by the authors (EH, HLK and KB) during their careers as neonatologists. The cases included scenarios such as communicating with a parent dissatisfied with his infant's care; with parents upset about lack of information about their child's medical condition; with parents who are disappointed because their infant's transfer to another hospital is delayed; with parents who are distressed by their infant's deterioration; and with parents demanding information about results of medical examinations that nurses are not competent to discuss. The scenarios were given in written form to the nurses at the beginning of the workshop. After reading the scenario, the nurses discussed the case and suggested possible ways to deal with the communication issues. The items discussed included how to take into account parents' needs in the NICU, how to enhance their participation in the care of their infant, identifying and responding to the feelings that parents expressed, how to give information, the professional role of nurses, who should inform parents about different issues, and how to handle their own feelings. The nurses were also encouraged to express the feelings that the communication situations evoked in them. The course was learner‐centred, and the mentors' role was to encourage the nurses to suggest and discuss ways to deal with the difficult communication situations.

Nurses

The nurses working in the NICU were informed about the present study, which included a course in communication skills, audio recording of nurse–parent interactions before and after the course and a questionnaire addressing the nurses' perceptions of the quality and usefulness of the course for their daily job at the NICU.

Seventeen nurses volunteered to participate in the study and signed the informed consent form. Conversations between these nurses and parents were audio recorded before the nurses participated in the course. Due to maternity leave, illness, moving to another city or not working clinically after the course, four of the nurses could not be audio recorded after the course and were therefore excluded from the analysis. A total of 13 nurses were thus included in the study. The mean age of the nurses was 47 ± 2.9 years (median 44 years, range 28–60 years). They had been working in a neonatal unit for 12.8 ± 2.3 years (median 11 years, range 3.5–25 years).

Parents

All parents who had an infant at the NICU were eligible to participate in the study except parents with insufficient knowledge of the Swedish language to be able to converse with the nursing staff without an interpreter. 31 families (62 parents) and 34 families (68 parents) were given information about the study before and after the course, respectively. Of these, 26 families (84%, 52 parents) and 30 families (88%, 60 parents) agreed to participate and signed the informed consent form before and after the course, respectively.

Presence of parents at the NICU

After the birth of a sick infant, both parents are given parental leave in Sweden for the whole duration of the hospitalisation so that they are able to spend time in the NICU with their infant. Accordingly, both parents were present during many nurse–parent conversations. Both parents were present in 67%, just the mother in 17%, and just the father in 17% of the precourse conversations. Both parents were present in 49%, just the mother in 40% and just the father in 11% of the postcourse conversations. In cases where both parents were present, they were usually active in the conversations at the same time, completing one another's comments or questions. Their word counts were therefore combined when the conversations were analysed.

Characteristics of infants

The mean gestational age and birth weight of the infants whose parents participated in the precourse encounters were 33 weeks + 5 days ± 1 week + 4 days (median 35 weeks + 5 days and range 25 weeks + 6 days to 42 weeks + 0 days) and 2580 g ± 266 g (median 2595 g and range 870–4670 g), respectively. The infants whose parents participated in the postcourse conversations had a mean gestational age and birth weight of 35 weeks + 1 day ± 1 week + 1 day (median 33 weeks + 3 days and range 23 weeks + 4 days to 42 weeks + 3 days) and mean birthweight of 2263 g ± 327 g (median 1698 g and range 670–4845 g), respectively. These differences were not statistically significant.

Audio recording

Nurse–parent encounters were recorded before and after the communication course by HW, HK and ML. These encounters could be any conversations between the nurses and parents, except interactions occurring during critical situations such as a dying baby or an ongoing resuscitation. In these cases, the authors felt that audio recording would have interfered with the parents' need for privacy, detracted from their concentration on the infant's condition, or otherwise burdened the parents, and would therefore have been unethical.

The nurses' names were coded, so that their identity was not disclosed. The names of infants and parents were not recorded. The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim, and the transcriptions were analysed blindly and independently by four of the authors (KB, HW, HK, ML).

Data analysis

Classification of words in the conversations

All expressions in the transcribed conversations were classified into the following five categories, and the words in the expressions were counted separately by each person analysing the transcriptions:

Physical: expressions directly related to the child's illness and care, for example nursing care, nutrition, equipment or laboratory tests.

Practical: expressions of practical aspects not directly related to the care of the infant, such as information on hospital rules, insurance, times of rounds or times and other practical issues related to moving the baby to other hospital or to home healthcare.

Psychological: expressions of feelings such as distress, frustration, disappointment or sadness.

Social: expressions concerning the life of the family outside of the hospital, for example finances, work, siblings, grandparents or friends.

Small talk: expressions about issues such as the weather, shopping or current events.

The mean number of words was calculated from the tallies obtained by the four authors who analysed the transcriptions.

Empathic opportunities

The number of empathic opportunities, defined as expressions of emotions, stressors or concerns, was counted independently by four of the authors (KB, HW, HK, ML). The nurses' responses to each empathic opportunity were classified independently by each author as belonging to one of the following categories:

Empathic response: the nurse recognised the parent's feeling, understood the reason for the feeling and responded by acknowledging the feeling 15.

Exploring response: in situations where the feeling of the parent and/or its cause were unclear, the nurse asked follow‐up questions to find out what the parent was feeling and what caused him or her to feel that way 15.

Generalising response: the nurse generalised the parent's feeling, for example by saying ‘most parents feel like that' or ‘parents get used to it'.

Ignoring response: the nurse ignored the parent's expression of emotion and changed the subject or ended the conversation.

Giving inadequate advice: the nurse gave advice to the parent without addressing the parents' feeling or its cause.

In the rare cases where the authors' assessments of the empathic responses were different, disagreements were discussed by these four authors as a group, and final decisions were made by consensus 8.

Expressions of interest in the parent's well‐being

The nurses' spontaneous expressions of interest in the well‐being of parents were also counted by the authors. These expressions were either statements expressing caring for the parents or questions about how the parents were doing or coping. The questions were classified as closed, that is questions that can be answered with yes or no, or open, that is questions inviting other answers.

Engaging parents in the care of the infant and giving feedback

Expressions used by the nurses to engage parents in the care of their infant were counted by the authors and classified as an encouragement or command/order. The care could be any intervention such as changing the diaper, bathing the infant, breastfeeding, giving a nasogastric tube feed, taking the baby out of the isolette, holding the baby skin‐to‐skin etc. Expressions of positive feedback given by the nurses to parents participating in their infant's care were also counted.

Questionnaire

One and six months after the course, the nurses were given a questionnaire consisting of eight questions. Some of the questions could be answered with a five‐step Likert‐like scale, and others with yes/no/don't know. The nurses were encouraged to write freely worded comments after each question. In addition, they were asked to write general comments about the course.

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as means ± SEM. For comparisons between the number of words in the conversations, the two‐tailed Mann–Whitney test was used. The two‐tailed Wilcoxon signed‐rank test was used to compare the performance of individual nurses before and after the course. The relation between categorical variables was analysed using the two‐tailed Fischer's exact test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Content of nurse–parent communication in the NICU

We analysed 36 and 45 nurse–parent encounters audio recorded before and after the communication course, respectively.

The mean total numbers of words used by the nurses and parents in conversations before and after the course are shown in Figure 1A. The nurses talked much more than the parents during conversations both before and after the communication course. However, the difference was smaller after the course than before the course. The mean ratio between the nurses' number of words and the parents' number of words in the conversations was 3.7 ± 0.7 before the course and 2.0 ± 0.2 after the course (p = 0.003), implying that the nurse‐centredness of the conversations decreased after the course.

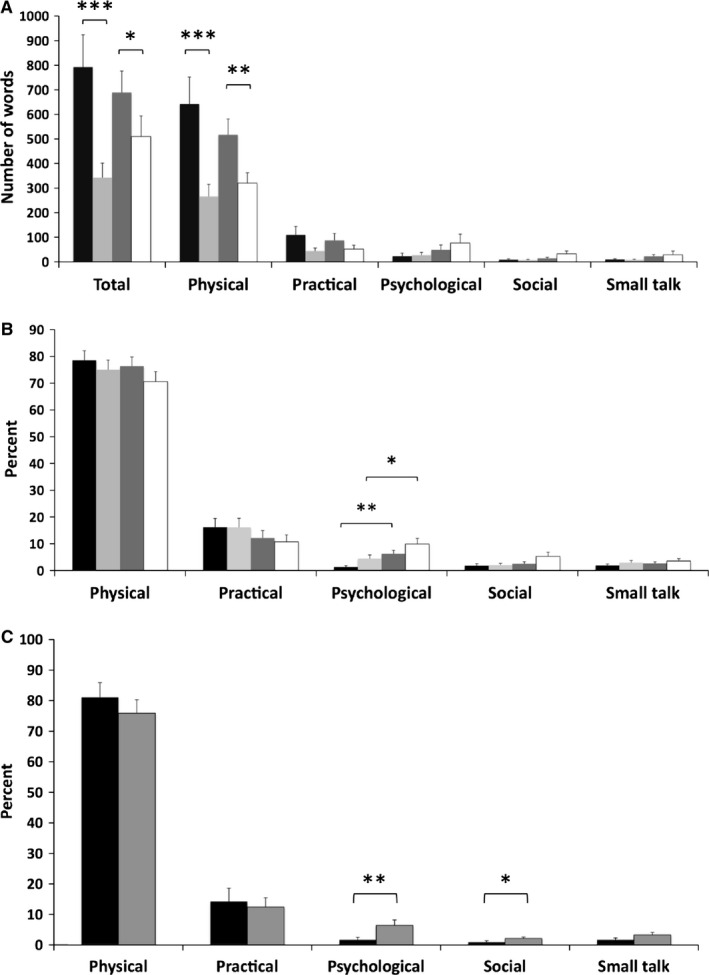

Figure 1.

The number of words in the precourse and postcourse conversations (A) and their percentual distribution (B) in the different categories. (A) and (B): Black, nurses before the course; light grey, parents before the course; dark grey, nurses after the course; white, parents after the course. ***, p < 0.0001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Mann–Whitney test. (C) Pairwise comparison of the precourse and postcourse percentages of words in the different categories for each individual nurse. Black, nurses before the course; dark grey, nurses after the course. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Wilcoxon signed‐rank test.

Not surprisingly, the conversations mostly concerned the illness and care of the infant (i.e. words classified as ‘physical'), followed by practical issues not directly related to the infant's care, such as times, schedules, hospital rules (classified as ‘practical') (Fig. 1A). In both of these categories, the nurses used more words than the parents both before and after the course (Fig. 1A). Relatively few words in the conversations were in the categories ‘psychological', ‘social' and ‘small talk' (Fig. 1A). The percentual distribution of the words for the precourse and postcourse conversations is shown in Figure 1B. 70‐80% of the words in the conversations addressed the infants' illness and care, whereas 10–15% were related to practical matters. The percentage of words that addressed psychological issues increased for both nurses (p = 0.0026) and parents (p = 0.011) after the course (Fig. 1B).

The percentual distribution of words in the various categories (physical, practical, psychological, social and small talk) before and after the course was also analysed separately for each nurse (Fig. 1C) to see whether the course made a difference to what the nurse talked about. On average, each individual nurse spoke more about psychological matters after the course than before (1.7 ± 0.8% before and 6.4 ± 1.8% after the course, p = 0.0046). The nurses' use of expressions belonging to the category ‘social' likewise increased from a mean of 0.9 ± 0.5% to 2.1 ± 0.5% (p = 0.039). Their use of language belonging to the category ‘small talk' increased from 1.7 ± 0.6% to 3.3 ± 0.8%, but this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.057). No significant differences were found in the other word categories when the nurses' performances before and after the course were compared.

Responses to empathic opportunities

The total number of empathic opportunities in the conversations was 62 before the communications course and 84 after the course. Thus, the mean number of empathic opportunities per conversation was 1.7 ± 0.4 before and 1.9 ± 0.4 after the course. This difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.25).

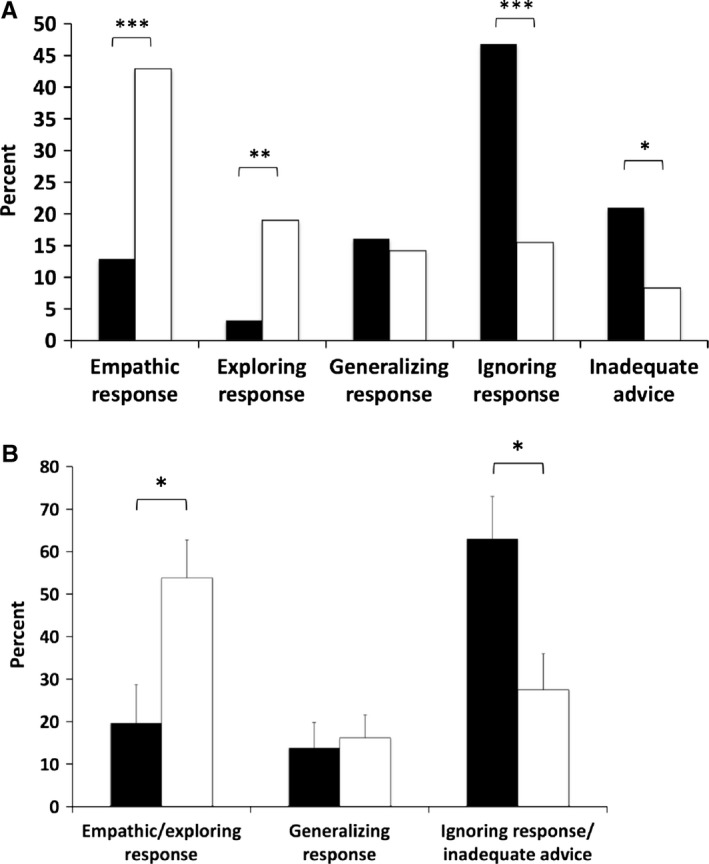

Overall, the nurses responded to 12.9% of the empathic opportunities with an empathic response before the course. The percentage of empathic responses increased to 42.9% after the course (Fig. 2A). Exploring the causes of the feelings expressed by the parents was rare at 3.2% prior to the course but increased after the course to 19.0%. The percentage of generalising was very similar before and after the course (16.1% and 14.2%, respectively). Before the course, the most prevalent response to empathic opportunities was ignoring (46.8%). This response decreased to 15.5% after the course. Likewise, giving inadequate advice likewise decreased from 21.0% before the course to 8.3% after the course (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

The nurses' responses to empathic opportunities in conversations audio recorded before and after the course. Black, precourse conversations; white, postcourse conversations.

To assess whether the course modified the individual nurses' responses to empathic opportunities, the responses to feelings expressed by the parents in the precourse and postcourse conversations were analysed separately for each nurse (Fig. 2B). As empathic and exploring responses can be considered equally valid responses to empathic opportunities 15, these responses were combined in this analysis. The use of these responses increased significantly (p = 0.027). The use of a generalising response, a less than optimal way of responding to an empathic opportunity, was similar before and after the course (Fig. 2B). Ignoring the empathic needs of parents by changing the subject or not answering at all and giving inadequate advice without recognising the parent's emotion or its cause are both poor responses to the empathic needs of parents; these inferior responses were also combined. The use of these responses decreased after the course (p = 0.043) (Fig. 2B).

Notably, the nurses' use of empathic or exploring responses did not correlate with their age or length of NICU experience (data not shown). Nor did the age or clinical experience of the nurses influence the degree to which their use of empathic or exploring responses was modified by the communication course (data not shown).

Involving parents in the care of their infant

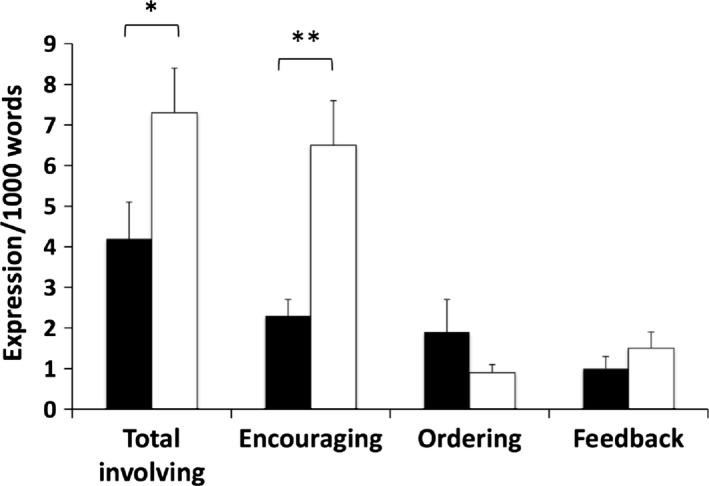

It is important for the parents of infants in the NICU to be able to participate in the care of their infant, both in order to enhance parent–infant bonding and to enable the parents gradually to take over care, so that they can eventually make a smooth transition to home. To assess whether the communication course modified the way in which the nurses invited parents to participate in the care of their infant, we counted and analysed the expressions nurses used to involve the parents in care. The mean number of such expressions was 2.8 ± 0.5 and 3.6 ± 0.5 per conversation for the precourse and postcourse conversations, respectively. This difference was not significant (p = 0.3).

To assess whether the course modified individual nurses' ways of involving parents in the care of their infant, we analysed the frequency at which each nurse encouraged or ordered the parents to care for their baby prior to and after the course. The number of times the nurse used encouragement or ordering was calculated for each conversation. To standardise for the variable length of the conversations, these numbers were divided by the number of words in the conversations. Encouraging parental participation increased after the course (p = 0.027) (Fig. 3), whereas the use of commanding expressions did not change significantly (Fig. 3). The frequency of expressions used to involve the parents in the care as well as the use of positive feedback tended to increase, but the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The nurses' use of expressions involving the parents in the care of their infant in conversations audio recorded before and after the course. The number of expressions were calculated per 1000 words to standardise for the variable length of the conversations. Black, precourse conversations; white, postcourse conversations. **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05. Mann–Whitney test.

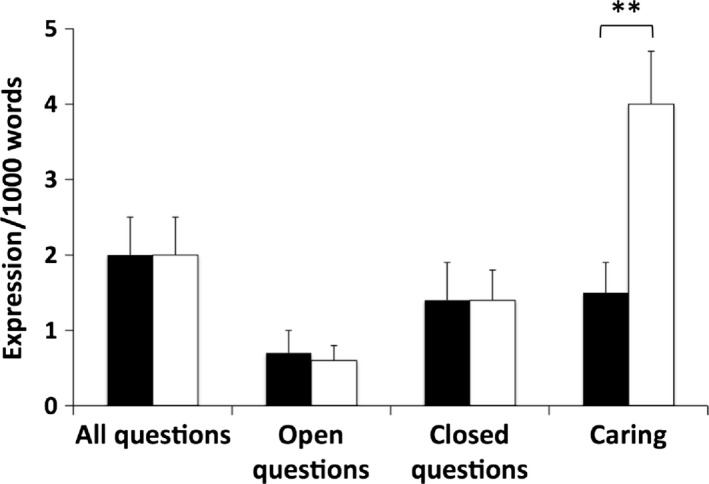

Nurses' spontaneous expressions of interest in parents' well‐being

Attention from nurses may help parents cope with the stressful environment of the NICU. To assess whether the course had an impact on individual nurses' use of expressions of interest in the parents' well‐being, we counted the number of times each nurse expressed caring for the parents or addressed a question to the parents about how they were doing or coping in the pre‐ and postcourse conversations. Statements expressing caring for the parents included comments such as ‘Let me fetch you a chair so that you can sit down' or ‘I'll put the blanket over your lap so that you can be more comfortable'. Questions were classified as open or closed. To calculate the frequency of these expressions of interest in the encounters, the number of expressions was calculated per 1000 words in the conversation (Fig. 4). The course did not change the frequency of questions addressed to the parents about how they were doing. Both before and after the course, the majority of the questions addressing the parents' well‐being were closed ones (Fig. 4). The use of open questions tended to increase after the course, but the difference was not statistically significant. In contrast, the nurses' use of phrases expressing caring for the patients was significantly higher after the course than before (p = 0.0034) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The number of questions the nurses asked about how parents were doing and nurses' statements expressing caring for the parents in conversations before and after the course. To standardise for the variable length of the conversations, the number of expressions were calculated per 1000 words in the conversations. Black, precourse conversations; white, postcourse conversations. **, p < 0.01. Mann–Whitney test.

The nurses' opinions of the communication course

To assess the nurses' opinions about the course, they were given a questionnaire containing questions about the course one and six months after the course. At both times, 11 of the 13 nurses answered the questionnaire. Their answers were very similar at one and six months, and the results of both time points are combined in Table 1.

Table 1.

The nurses' answers to the questionnaire. The percentages of the answers received one and six months after the course have been combined

| Questions with Likert‐like scale | 1 (%) | 2 (%) | 3 (%) | 4 (%) | 5 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How satisfied were you with the course in communication techniques? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 91 |

| How useful was the course for your job in the NICU? | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 95.5 |

| Questions with No/Yes answers | No (%) | Yes (%) | Don't know (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Did the course increase your knowledge of what communication is and of the elements that communication consists of? | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Has the course had an effect on the way you communicate with parents? | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Has the course made you more confident in your professional role when communicating with parents? | 22.7 | 77.3 | 0 |

| Has the course made it easier for you to talk with parents of other things besides the child's care? | 81.8 | 18.2 | 0 |

| Has the course influenced the way you communicate with colleagues and other personnel in the NICU? | 45.5 | 50 | 4.5 |

| Do you feel that you would need more training in communication techniques? | 27 | 64 | 9 |

The number of nurses is shown with the percentage in parentheses. For the Likert‐like scale, 1 = very dissatisfied or entirely useless; 5 = very satisfied or very useful.

Satisfaction with the course

At both one and six months after the course, 10 of the 11 nurses were very satisfied with the course (Table 1). In their freely worded comments, most stated that the course had enhanced their awareness of the major importance of communication for their job and had given them useful tools for their daily work in the NICU.

Learning communication skills was an incredible opportunity to develop professionally in one's role as a nurse.

I can understand communication and its importance in a new way. My work is based on communication. Good communication is the route to confident parents.

The combination of theory about communication techniques and clinical case scenarios was great.

The discussions in small groups were great. Everybody could express their opinions.

Usefulness of the course and its effect on the nurses' communication with parents: reflecting about communication situations and listening skills

The nurses reported that the course had been very useful for their work in the NICU, and all of them felt it affected their way of communicating with parents (Table 1).

Several nurses stated that the course had helped them to be more structured in their conversations and that they had started to think beforehand about the best way to bring up the subjects they needed to discuss. They had also started to reflect upon the way of communication that worked best for them in different situations. They commented that they were more aware of the importance of nonverbal communication, such as body language, together with privacy and the setting in which a conversation takes place. Some of the nurses felt that the course had made them think more about how to make parents feel welcome at the unit. The nurses felt that the course had made them more attuned to parents' needs and had taught them to listen to parents, letting them express themselves before intervening.

I have learned to be more sensitive to parents and to listen more to what parents have on their minds. Sometimes it is difficult for them to say what they are worried about.

I try to take a more passive role and let them express what they think.

I think more than before about what I say and how it influences parents.

On the other hand, one of the nurses commented that when the stress level and work load at the unit were very high, it was difficult for her to practice the communication skills she had been taught on the course.

Professionalism and confidence in communicating with parents and handling parents' questions and emotions

Most of the nurses felt that the course had increased their confidence in communicating with parents (Table 1). In their freely worded comments, many nurses stated that the communication course had helped them feel more comfortable talking to parents. They also felt it was easier for them to listen to parents and to tolerate silence instead of intervening immediately when there was a pause in the conversation.

The course had also made some of the nurses more secure in their professional role. For example, they felt that they could admit to parents that some questions were outside their area of expertise. Some nurses commented that they did not feel compelled to speak as much as before about medical issues. In addition, some nurses felt it had become easier for them to end a conversation because of lack of time and schedule a follow‐up conversation with parents.

I have learned to say: I don't know but I'll find out and will get back to you.

I have learned to limit the information I give to what I know and can give answers about.

I am no longer afraid of short encounters with parents when I am in a hurry. It has been difficult for me to end them, and I have received tips about how to do it.

In their freely worded comments, several nurses wrote that the course had helped them handle parents' worries and distress. They felt that they took more time to listen to the parents and that they were more prepared to ask the parents how they could help. They also said that the course had made them more comfortable in responding to and eliciting parents' expressions of emotions without taking them personally. They felt that the course had made it easier for them to speak with parents about emotionally difficult subjects without becoming too deeply emotionally involved and that this confidence had lessened their own fear and anxiety in the face of difficult conversations. A major aspect the nurses reported having learned was consciously responding with empathy to parents' expressions of emotions or stress.

I talk more about how parents feel.

I find it easier to encounter strong feelings on the part of the parents. I take them less personally than before.

Do you feel the need for more education in communication?

Most of the nurses felt that they needed more training in communication (Table 1), and several nurses would have liked a refresher course with a similar set‐up to the present one. They also felt that all the nurses, and also the physicians at the unit, should be given the possibility to take the course. One nurse commented that the course should be compulsory for all personnel involved in the care of the infants. Some nurses wrote that they would like to have a longer course with more clinical cases. Some nurses also wished to have continuous mentoring in communication at the NICU, and some wanted training in communicating with families from other cultures.

Communication with parents is a central part of our work and we need continuous teaching in communication skills.

Discussion

In the present study, a communication course was given to nurses working at a level III NICU. The content of nurse–parent interactions at the NICU, the way the nurses responded to the parents' feelings, their spontaneous expressions of interest in the parents' well‐being, as well as the ways in which they involved parents in the care of their infant were analysed in audio recorded conversations of the nurses with parents before and after the course.

To quantify the content and orientation of the conversation, we classified all expressions in the conversations into five categories – physical, practical, social, psychological and small talk – and counted the words in the expressions. Although the nurses spoke more during the conversations than the parents both before and after the course, the postcourse encounters were less nurse‐centred than those recorded before the course. As expected, the major part of the conversations dealt with the infants' illness and care. The second‐largest part concerned practicalities such as hospital rules and schedules. Other areas, including psychological aspects or social matters such as the family's life outside of the hospital, were rarely talked about. The nurses talked more about psychological and social issues after the course than before. There was almost no small talk in the encounters. Previous studies have suggested that the use of small talk or chatting may be important in initiating and enhancing positive interactions with parents 18. It is possible that the nurses were too busy to bring up issues not directly related to the infant's illness or care. On the other hand, the parents might have felt reluctant to talk about such things so as not to draw the nurse's attention away from the infant 19.

The nurses responded empathically to only 13% of the feelings expressed by parents in the conversations audio recorded before the course. This result is consistent with previous studies on cancer patients, which demonstrated that physicians and nurses rarely respond to patients' emotions with empathy 6, 7, 8, 9, 10. After the course, the nurses responded to 54% of the patients' emotions with empathy, meaning that the use of empathic responses more than tripled. In addition, the nurses explored the causes of the parents' feelings much more often after the course than before. Before the course, almost half of the emotions expressed by parents were ignored by the nurses, whereas after the course only 16% were ignored. The use of empathic or exploring responses was also significantly higher after the course when analysed separately for each nurse, whereas ignoring the parents' feelings or giving inadequate advice decreased.

Parents appreciate nurses who see them as individuals and show an interest in them, whereas those who treat parents as irrelevant or ‘just another parent' are perceived as ineffective communicators 3. We analysed how often the nurses expressed caring for the parents or asked questions about how they were doing or coping. After the course, there was a highly significant increase in the nurses' use of statements that showed caring for the parents.

Promoting parenting skills and involving families in the care of their hospitalised infant is important for parents 20. Missed opportunities to participate in the care of the infant can increase parental anxiety and sadness 21. Parents perceive encouragement and politeness and a respectful attitude on the part of nurses as effective communication strategies, whereas demanding or commanding is perceived as ineffective 3. Mothers also value being given positive feedback about their parenting 3. We analysed how often, and in what way, the nurses asked the parents to provide care for their infant as well as how often positive feedback was given. Although the nurses mostly asked the parents politely, and did not impose, in some cases nurses' instructions were expressed as orders. The use of kind encouragement was more common after the course than before. The frequency of giving positive feedback was not changed by the course.

The nurses who participated were very satisfied with the course. They felt that it had increased their awareness of the importance of communication in their work and influenced their way of communicating. Many nurses thought that the course had enhanced their listening skills. In agreement with the quantitative results of the study, most nurses felt that they were more comfortable encountering parents' emotions and responding to them after the course than before. The nurses reported that this confidence had lessened their fear and anxiety in facing difficult conversations. This is important, as poor communication is a major source of stress for nursing staff in intensive care units 22. Many of the nurses thought that the course should be obligatory for all personnel. They also wanted to participate in a follow‐up course.

To our knowledge, this is the first quantitative study about the content of nurse–parent encounters in a NICU. Previous studies addressing the ability of neonatal nurses to identify and respond to parents' emotions are also lacking. We were able to show that a brief course in communication techniques significantly improved the nurses' performance in this respect.

The nurses volunteered to participate in the study and agreed to be audio recorded and thus represented a motivated group interested in learning communication skills. The results of the study therefore cannot be generalised to an unselected group of nurses. In addition, the nurses were from only one hospital, so the results cannot be generalised to other settings. The study had a short follow‐up period, as the postcourse conversations were audio recorded within 2 months after the communication course. We therefore do not know whether the skills learned during the course were persistent. We were not able to account for empathic opportunities expressed nonverbally for example with body language or tone of voice, nor were we able to analyse possible nonverbal communication expressing empathy, such as giving a hug.

Conclusions

Although communication with parents is an important part of nursing care in the NICU, neonatal nurses have generally not been trained in communication skills. We have shown that a short course in communication techniques improved the capacity of neonatal nurses to respond with empathy to feelings expressed by parents and made them more attentive to parents' well‐being. Better communication skills may make the NICU experience more satisfactory for parents and at the same time decrease the stress of nurses working at the NICU. In addition, better nurse–parent communication is likely to promote parents' participation in the care of their infant and thereby make neonatal care more family‐centred.

Financial support

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, the Frimurare Barnhus Foundation and the Swedish Research Council for Clinical Research in Medicine.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the nurses and families who participated in this study.

References

- 1. De Rouck S, Leys M. Information needs of parents of children admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit: a review of the literature (1990–2008). Patient Educ Couns 2009; 76: 159–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitfield MF. Psychosocial effects of intensive care on infants and families after discharge. Semin Neonatol 2003; 8: 185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jones L, Woodhouse D, Rowe J. Effective nurse parent communication: a study of parents' perceptions in the nicu environment. Patient Educ Couns 2007; 69: 206–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Reis MD, Rempel GR, Scott SD, Brady‐Fryer BA, Van Aerde J. Developing nurse/parent relationships in the nicu through negotiated partnership. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2010; 39: 675–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zwaanswijk M, Tates K, van Dulmen S, Hoogerbrugge PM, Kamps WA, Beishuizen A, et al. Communicating with child patients in pediatric oncology consultations: a vignette study on child patients', parents', and survivors' communication preferences. Psychooncology 2011; 20: 269–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morse DS, Edwardsen EA, Gordon HS. Missed opportunities for interval empathy in lung cancer communication. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168: 1853–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Abernethy AP, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25: 5748–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Alexander SC, Pollak KI, Morgan PA, Strand J, Abernethy AP, Jeffreys AS, et al. How do non‐physician clinicians respond to advanced cancer patients' negative expressions of emotions? Support Care Cancer 2011; 19: 155–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levinson W, Gorawara‐Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA 2000; 284: 1021–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner J, Shields CG. “Could this be something serious?” Reassurance, uncertainty, and empathy in response to patients' expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med 2007; 22: 1731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V, Farewell V, Saul J, Duffy A, Eves R. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 359: 650–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fallowfield L, Jenkins V. Communicating sad, bad, and difficult news in medicine. Lancet 2004; 363: 312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stiefel F, Barth J, Bensing J, Fallowfield L, Jost L, Razavi D, et al. Communication skills training in oncology: a position paper based on a consensus meeting among European experts in 2009. Ann Oncol 2010; 21: 204–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maguire P, Pitceathly C. Key communication skills and how to acquire them. BMJ 2002; 325: 697–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES‐a six‐step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000; 5: 302–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, Olsen MK, Jeffreys AS, Rodriguez KL, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer‐based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155: 593–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buckman R. Communications and emotions. BMJ 2002; 325: 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fenwick J, Barclay L, Schmied V. ‘Chatting': an important clinical tool in facilitating mothering in neonatal nurseries. J Adv Nurs 2001; 33: 583–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Padden T, Glenn S. Maternal experiences of preterm birth and neonatal intensive care. J Reprod Infant Psychol 1997; 15: 121–39. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harrison H. The principles for family‐centered neonatal care. Pediatrics 1993; 92: 643–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cockroft S. How can family centred care be improved to meet the needs of parents with a premature baby in neonatal intensive care? J Neonatal Nurs 2012; 18: 105–10. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, Tieszen M, Kon AA, Shepard E, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient‐centered intensive care unit: american college of critical care medicine task force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: 605–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]