Abstract

Background

There are limited evaluation and treatment options for low libido in premenopausal women. This review sought to evaluate the available evidence supporting the evaluation of testosterone serum levels and testosterone treatment of premenopausal women with low libido.

Methods

MEDLINE, PubMed, and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched for articles that referenced the evaluation of testosterone serum level and/or testosterone treatment on premenopausal women with low libido from 1995 to 2015. Additional references were obtained from the reference sections of other papers and from peer review. Studies that included only postmenopausal women were excluded. A total of 13 studies were reviewed in detail. Nine studies examined the relationship between testosterone serum levels and sexuality, an additional three studies examined the effect of testosterone treatment on premenopausal women with low libido, and one study examined both the topics.

Results

Six of the ten testosterone serum evaluation studies failed to show a significant association between testosterone serum level and libido. Only one out of four studies examining testosterone treatment in premenopausal women was able to show any clear improvement in libido; however, the effect was limited to only the intermediate dose of testosterone, with the low and high doses of testosterone not producing any effect.

Conclusion

The currently available evidence does not support testosterone serum evaluation or treatment in premenopausal women with low libido. Hence, further studies are warranted.

Keywords: androgens, hypoactive sexual desire disorder, HSDD, ovary, testis, sexual dysfunction, sexual interest, arousal disorder

Introduction

In the United States, 40% of women self-report sexual dysfunction, with low libido (also known as sexual interest/arousal disorder) being the most common manifestation.1 At present, there is only one Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved pharmaceutical option (a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor [SSRI] named Flibanserin) to treat sexual interest/arousal disorder, leaving providers with few treatment options. One of the most frequently prescribed off label medications for premenopausal women with sexual interest/arousal disorder is testosterone. Although administration of testosterone seems logical based on its efficacy in hypogonadal adult males, the physiology of female libido does not seem to follow the same design. The available published literature on testosterone use in premenopausal women does not consistently show a correlation of low libido with low testosterone levels, and it does not consistently show an improvement in sexual problems with the addition of testosterone treatment. Despite these data, testosterone prescriptions in women have been increasing,2 which leaves us to ponder the role of testosterone in women.

Testosterone: from fetal development to adulthood

The fetal ovary is primarily involved in the production of gametes. Thus, by mid gestation of fetal life, the ovary consists of up to 8 million oocytes; however, it secretes only minimal amounts of steroids or estrogen.3 On the other hand, the fetal testes are not involved in gamete production but are involved in secreting enormous amounts of testosterone in levels similar to that seen in adult males.4 Thus, a female fetus and female newborn have little, if any, exposure to circulating androgens because of the elevated sex hormone-binding globulin in the mother and high expression levels of aromatase in the placenta.5 It is not until puberty that a female is exposed to small amounts of rising androgen levels.

In the pubertal or postpubertal female, the majority of circulating testosterone is not formed by direct secretion from the ovary, but rather, it is peripherally converted from androstenedione (A) and dehydroepiandrosterone. It has been estimated (from data collected from a few women undergoing ovarian and adrenal venous sampling at the time of oophorectomy for benign indications) that only up to 25% of circulating testosterone in non-hirsute women is from direct secretion.6

In fact, the mechanism whereby androstenedione is converted to testosterone is through the enzyme 17 beta hydroxyl steroid dehydrogenase Type 3 (17BHSD Type 3). A previous study investigated and reported that the human ovary does not express 17BHSD Type 3 by northern analysis or polymerase chain reaction.7 However, extremely high levels of this enzyme are expressed in the human testis.

If one compares the circulating levels of testosterone in men (350–1,030 ng/dL), they are ten times greater than those in women (10–55 ng/dL).8 Given the large difference in normal testosterone levels between males and females, what, if any, role does testosterone play in normal female physiological processes? First, it is clear that the role of testosterone in males begins in utero with the development of the male genitalia, internal wolffian ducts, and prostate gland.5 Again, at puberty, testosterone levels rise to cause muscle development, deepening of the voice, facial hair development, and temporal hair loss. Since this does not occur in the majority of normal women, we are left to contemplate what the role of testosterone in women is. Some hypothesize that testosterone may be important for female libido. While the physiologic role of testosterone in women cannot be definitively defined yet, this review presents evidence indicating that the simplistic evaluation of testosterone levels and treatment with testosterone is not an evidence-based approach for sexual interest/arousal disorder.

Sexual dysfunction diagnosis and classification

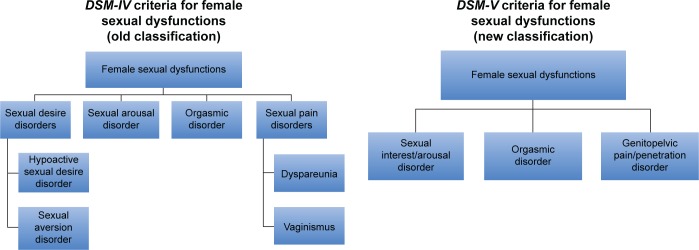

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association published the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), with changes, simplifying the classification of sexual dysfunctions from four categories to three categories (Figure 1).9–11 The previous categories of female hypoactive desire disorder and female arousal dysfunction were combined into a single syndrome called sexual interest/arousal disorder. Also, the newly introduced syndrome termed “genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder” combines the formerly separate dyspareunia and vaginismus disorders. In order for a patient to meet the diagnostic criteria for one of these sexual disorders, the DSM-V criteria require symptoms to be present for a duration of at least 6 months and that those symptoms cause significant distress to the patient. In addition, the dysfunction cannot be better explained by a nonsexual mental disorder or by severe relationship distress.10,11 Although it is important to have a simple and clear diagnostic classification system, the recent classification change can make interpretation and comparison of past studies to present studies more complex.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the old and new classifications for female sexual dysfunction.

The initial approach to a patient who presents with a possible sexual dysfunction is referred to a healthcare professional who is comfortable and experienced with the topic. Obtaining a medication history is of paramount importance since numerous prescription and over-the-counter medications have been associated with sexual dysfunction. Management is ideally multidisciplinary and can often include gynecologists, reproductive endocrinologists, anesthesiologists, mental health therapists, pelvic floor physical therapists, and if an organic cause is suspected, a gastroenterologist and urologist.

The use of androgen supplementation for female sexual dysfunction stems from the knowledge that androgen levels decrease with age.12,13 The theorized potential benefits of testosterone treatment are an increase in sexual desire and sexual activity. However, the beneficial effects have been observed with relatively high doses, and there is a paucity of long-term prospective data on the use of testosterone therapy for female sexual dysfunction. Men who have low levels of testosterone (Low T) exhibit reduced sexual desire and libido as well as reduced erections. The diagnosis depends on a testosterone serum level that is <300 ng/dL.14 Thus, men with a level ~200 ng/dL often experience these symptoms. To put this in perspective, most studies report a slight increase in sexual arousal in women treated with testosterone. However, this occurs if levels of testosterone reach 80–150 ng/dL. These high levels, over time, may result in masculinization with potential hirsutism, clitoral enlargement, deepening of voice, and hair loss.15,16 Since men have been shown to experience decreases in libido at testosterone serum levels of <300 ng/dL, a female would theoretically have to reach a similar serum level in which further masculinization could result.14

Proposed mechanisms by which testosterone may affect libido

As mentioned earlier, female androgens are produced by the ovary, adrenal gland, and peripheral conversion, and testosterone is the most potent of these androgens. In some tissues, it must be metabolized to dihydrotestosterone (DHT) to give its full effect. Testosterone levels vary throughout the menstrual cycle and have a diurnal pattern. DHT levels have been found to be correlated with male sexual activity, but not with female libido.17,18

Experiments in nature

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS is a condition that is well known to be associated with elevations in testosterone. However, this increase in testosterone does not result in increased libido.19 In fact, it may cause a decrease in libido, possibly due to body image issues associated with hirsutism and other signs of androgen excess.

Surprisingly, when PCOS patients started on oral contraceptives to reduce hyperandrogenism and testosterone levels, desire was found to be increased.20 Even a large synthesis of 36 studies (13,673 women) on normal women who started on oral contraceptive pills reported that 85% of women had an increase or no change in libido while on oral contraceptives.21 Only 15% of women on oral contraceptives reported decreased libido despite most studies showing a decline in the plasma levels of free testosterone.

Androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS)

Complete AIS is a disorder in which the lack of functional testosterone receptors results in male feminization. Despite a complete lack of functional testosterone receptors, studies have shown that patients with AIS do not have a higher incidence of low libido/desire.22 In fact, one study showed that 71% of AIS patients reported libido of average or stronger and 77% reported the ability to have an orgasm.22 This implies that libido is not dependent on the direct action of testosterone on the testosterone receptor and that a more complicated mechanism is likely.

Systematic review of testosterone serum evaluation and treatment in premenopausal women

Objectives

The objective of this review was to examine the evidence in premenopausal women who would show a link between low testosterone levels and libido, as well as to review the evidence behind the administration of testosterone for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction.

Methods

Two separate reviews were performed:

Review of all the evidence that showed a link between low testosterone levels and low libido in premenopausal women.

Review of all the evidence that examined the effect of testosterone treatment in premenopausal women with low libido.

MEDLINE, PubMed, and ClinicalTrial.gov were searched for all relevant studies, published from 1995 to the present, that examined the correlation of testosterone levels in premenopausal women with libido using relevant search terms. The second search was performed using relevant search terms to identify studies that evaluated testosterone treatment in women. The reference sections of the identified manuscripts were also searched to identify and review all other relevant studies. An additional study was added during the peer review process. We acknowledge that publication bias may result in the publication of mostly positive findings.

Study selection

Review papers were excluded. Only clinical trials involving human female premenopausal women were included. While studies utilizing only postmenopausal women were excluded, this review included studies that had both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Studies that examined the correlation of testosterone level with other disease types or symptoms were excluded. Studies evaluating the use of testosterone for other than sexual purposes (such as transgender treatment) were excluded. Studies that examined testosterone use in postmenopausal women were excluded. Studies that used a combination of testosterone treatment with antidepressants were excluded.

Results

Results for testosterone level and libido correlation review

Our literature resulted in a list of 256 references. After reviewing the article title and article type, 249 articles were excluded. The reference review and peer review allowed the addition of three more articles resulting in a total of ten papers to review (Table 1).

Table 1.

Studies that examined serum testosterone levels and sexual desire

| Authors | Study population | Testosterone serum levels | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wåhlin-Jacobsen et al23 | 560 women (included premenopausal and postmenopausal women) Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, nursing, postpartum, thyroid disease, pituitary disease, PCOS, cancer, use of antidepressants or antipsychotics |

Means not given | No correlation between total testosterone and sexual desire in the cohort A statistically significant correlation was found between sexual desire and free testosterone in the cohort. However, on subanalysis, this correlation persisted only in women aged 19–24 years. The correlation did not persist in women aged 25–65 years |

| Basson et al24 | 245 women (included premenopausal and postmenopausal women) Exclusion criteria: depression, abnormal body mass index, current use of sex hormones or medications known to affect libido, medical conditions known to inhibit sexual function, dyspareunia, substance abuse, smoking, severe relationship discord, lack of English fluency |

Control group: Total testosterone: 21 ng/dL (±0.1 SD) Sexual dysfunction group (generalized sexual desire and arousal disorders): Total testosterone: 19 ng/dL (±0.11 SD) |

No differences in testosterone levels between women with sexual dysfunction and controls |

| Alder et al25 | 29 premenopausal women with Stage I or II breast cancer Exclusion criteria: major psychiatric disorders, cardiovascular, metabolic, or neurological disease |

Chemotherapy group: Total testosterone: 14 ng/dL (±0.05 SD) No chemotherapy group: Total testosterone: 13 ng/dL (±0.07 SD) |

Testosterone levels did not predict sexual dysfunction |

| Elaut et al30 | 92 women (62 transsexual [castrated male to female] women and 30 ovulating women) Exclusion criteria: use of steroidal contraception, use of medication that could influence androgen levels or sexual desire, alcoholism, cirrhosis, Cushing syndrome, hyper and hypothyroidism |

Transsexual women: Total testosterone: 20 ng/dL (±9.6 SD) Free testosterone: 0.26 ng/dL (±0.16 SD) Ovulating women: Total testosterone: 33.9 ng/dL (±17.9 SD) Free testosterone: 0.5 ng/dL (±0.31 SD) |

Transsexual women had lower free and total testosterone, but these levels did not correlate with a higher risk for HSDD Ovulating women demonstrated a correlation between free and total testosterone and solitary sexual desire. However, the correlation did not hold true for dyadic sexual desire Reference ranges provided in this study: Total testosterone: 10–80 ng/dL Free testosterone: 0.2–0.5 ng/dL |

| Turna et al31 | 40 premenopausal women, 40 postmenopausal women Among each group, half had decreased sexual desire and the other half were controls Exclusion criteria: adrenal insufficiency, thyroid disease, depression, chronic fatigue syndrome, chronic metabolic disease, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy |

Overall mean serum values not reported | Decreased free testosterone and total testosterone were correlated with lower female sexual function indexes. However, all mean serum levels reported were considered to be within the reference range; however, the reference range used was not reported |

| Riley26 | 30 women (15 controls and 15 with sexual drive disorder) Exclusion criteria: genital atrophy or infection, sexual aversion, depression, and psychiatric disturbance. Use of medications that impair sexual function or disrupt hormonal control, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, smoking, pregnancy, recent childbirth, abnormal menses, and thyroid dysfunction |

Low libido: Total testosterone: 47 ng/dL Controls: Total testosterone: 60.5 ng/dL (no statistical difference) Low libido: Free testosterone index: 2.27% Controls: Free testosterone index: 3.92% (P=0.02) |

Women with lifelong absence of sexual drive had significantly lower levels of free testosterone index Free testosterone index did not correlate with the index of sexual desire The total testosterone levels were not different The authors reported that there were no testosterone levels below the reference range Reference range reported in this study: Total testosterone: 14–101 ng/dL |

| Santoro et al32 | 2,961 premenopausal women aged 42–52 years Exclusion criteria: could not have taken any hormones for at least 3 months prior to enrollment |

Total testosterone: Median: 41 ng/dL |

Authors reported that “Sexual desire was, at best, marginally related to circulating testosterone levels” |

| Davis et al27 | 1,021 women, aged 18–75 years. Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, postpartum, acute psychiatric illness, major illness, gynecological surgery, cancer, potentially confounding conditions, or medications | Not given | Authors reported that “The ROC curves provided no evidence for total or free testosterone being useful for discriminating between individuals with or without low sexual function” |

| Nyunt et al18 | 41 premenopausal women (29 with low libido and 12 controls), aged 18–45 years Specific exclusion criteria not given | Total testosterone: Low libido group: 28 ng/dL (±0.38 SD) Controls: 28 ng/dL (±0.41 SD) Free testosterone: Low libido group: 0.002 ng/dL (±0.02 SD) Controls: 0.002 ng/dL (±0.01 SD) |

No difference in testosterone or free testosterone levels between subjects and controls |

| Glaser et al29 | 108 premenopausal women, 192 postmenopausal women Exclusion criteria: breast cancer |

Values not given | Authors conclude “Our results showed that a single serum measurement of testosterone was not useful in the diagnosis of androgen deficiency. Neither the incidence/severity of symptoms nor treatment effect correlated with baseline free or total testosterone levels, consistent with previous studies” |

Abbreviations: HSDD, hypoactive sexual desire disorder; PCOS, polycystic ovarian syndrome; SD, standard deviation.

Seven out of the ten studies concluded that total testosterone was not related to libido or sexuality.23–29 Only three studies reported any correlation, but the evidence is weak. For example, Elaut et al’s study of 92 patients reported that there was a correlation between free testosterone levels and solitary sexual desire, but the correlation did not hold true for dyadic sexual desire (ie, sexual desire with a partner).30 Turna et al reported that total testosterone was associated with lower female sexual function indexes.31 However, all mean serum testosterone levels reported in the study were considered to be within the reference range, which limits the clinical usefulness of checking a testosterone serum level while evaluating a premenopausal woman who is reporting low libido. Santoro et al had the largest study and although they reported a correlation, they note that “Sexual desire was, at best, marginally related to circulating testosterone levels.”32

To summarize the table, studies attempting to show a correlation between low total testosterone serum level and free testosterone and low libido in premenopausal women have not been able to show consistent or reproducible findings.27 Furthermore, none of the studies were able to show a testosterone threshold level that would be deemed to be “too low.”

Results for testosterone treatment review

Our literature search on testosterone treatment for premenopausal women resulted in nine studies. Of these, two were reviewed and found to be eligible, and the other seven were out of topic. Another two studies eligible for review were identified by searching the reference sections of other studies and through the peer review process.

All four selected studies evaluate the role of testosterone given through different routes in the female sexual response (Table 2). Davis et al performed the largest premenopausal female study.33 She reported on 261 women with low sexuality scores who underwent testosterone treatment. Three different doses of transdermal spray were used and compared to placebo to assess for increase in the frequency of sexually satisfying events (SSEs) after 16 weeks. There were no changes in SSEs in either low-dose or high-dose testosterone spray, but there was an increase in SSEs from 1.7 to 2.48 using the intermediate dose of 90 µL. Interestingly, the testosterone serum level was lowest in the intermediate group when compared to any of the other groups. In fact, there was no relationship between testosterone levels and number of SSEs. Of note, the testosterone treatment groups reported more androgenic side effects (hypertrichosis and acne) than the placebo group.

Table 2.

Testosterone treatment in premenopausal females

| Authors | Study population | Treatment | Results | Testosterone serum levels | Androgenic side effects | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis et al33 | 261 premenopausal women with a low sexuality score Exclusion criteria: planning a pregnancy, pregnant, or breastfeeding. Relationship problems, dyspareunia, on medication known to interfere with normal sexual function, history of androgen therapy. Hirsutism, acne, cancer, major illness, genital bleeding, heavy alcohol use, drug addiction. 16-week treatment |

Placebo Low-dose transdermal testosterone spray Medium-dose transdermal testosterone spray High-dose testosterone spray |

No change in SSE in low or high dose when compared to placebo The intermediate dose had an increase in SSEs, 2.48 versus 1.7 in placebo |

Placebo: Total testosterone 24.2 ng/dL (±0.25 SD) Low dose: Total testosterone 42.4 ng/dL (±0.87 SD) Intermediate dose: Total testosterone 36.9 ng/dL (±0.46 SD) High dose: Total testosterone 56.8 ng/dL (±0.88 SD) |

81%–86% of the treatment groups report side effects Hypertrichosis 0% in placebo group 15.2%–28.4% in the treatment groups Acne 4.7% in placebo group 7.6%–9% in treatment groups |

The only group that had a statistically significant difference was the intermediate group (increase in SSEs, 2.48 vs 1.7 in placebo). However, the testosterone serum level in the intermediate group was actually lower than the serum level in the low- or high-dose groups |

| Goldstat et al34 | 34 premenopausal women with diminished sexuality Exclusion criteria: planning pregnancy, relationship problems, dyspareunia, taking medication known to affect sexual function, recent androgen treatment, acne, hirsutism, cancer, thromboembolic disease, major illness or disease, and heavy alcohol use 12-week treatment |

Placebo Testosterone cream |

Improvement in sexuality score (15.7 points) | Placebo: Total testosterone 31.4 ng/dL (±0.44 SD) Treatment: Total testosterone 74.4 ng/dL (±2.58 SD) |

None | While there was a statistically significant increase in the Sabbatsberg Sexual Self-Rating Scale with treatment, there was no statistically significant increase in the testosterone serum level when compared to placebo Reference range reported in this study: Total testosterone 14–78 ng/dL |

| Chudakov et al35 | Ten premenopausal women with HSDD Exclusion criteria: psychiatric disorders 4-week treatment |

Placebo Testosterone gel |

Increase in ease of arousal in testosterone gel group vs placebo (4.0 vs 4.4) No change in desire |

Not given | One report of slight increase of hirsutism | Did not increase libido |

| Glaseret al29 | 108 premenopausal women, 192 postmenopausal women with suspected androgen deficiency Exclusion criteria: breast cancer 12-week treatment |

Testosterone pellet (dose varied according to body weight and investigator judgment) No control group |

Increased urogenital subgroup score on the MRS noted after treatment. Score went from severe to mild (4.9 to 1.3). The urogenital subgroup scale evaluates sexual problems, bladder problems, and vaginal dryness |

Not studied | Authors report that some women reported a slight increase in facial hair, but they did specify how many women. 4.4% of women had increased irritability | While an improvement in the urogenital subgroup score was noted, the sexual problem score improvement in premenopausal women was not reported or discussed |

Abbreviations: HSDD, hypoactive sexual desire disorder; MRS, menopausal rating scale; SD, standard deviation; SSE, sexually satisfying event.

In the study by Goldstat et al, testosterone 1% cream was used at a dose of 10 mg per day and it was compared to placebo.34 The investigators found a statistically significant improvement in the scores of the sexual Sabbatsberg Sexual Self-Rating Scale and well-being scales, but no significant changes in the Beck Depression Inventory. The Sabbatsberg Sexual Self-Rating Scale is a multiple-choice questionnaire containing seven aspects of sexuality with a possible composite score range from 0 (low sexuality) to 84 (high sexuality). The increase in the testosterone cream group was by 15.7 points. Although score improvement in the testosterone group seems encouraging, the investigators found that the treatment group did not experience an increase in their serum testosterone levels. However, it is known that creams may offer inconsistent delivery due to colloidal settling of particles, so the route of delivery may have impacted the results. In addition, the study included only 34 subjects. There were no reported side effects, which is not surprising given that the testosterone serum levels did not increase when compared to placebo.

In the study by Chudakov et al, testosterone gel or placebo were used as needed 4–8 hours prior to intercourse.35 This study showed a slight increase in ease of arousal in the testosterone group with no changes in desire, lubrication, orgasm, or satisfaction. This study included only ten patients. The authors report an “increase” in sexual arousal as the placebo group scored a mean of 4.4 compared to 4.0 in the testosterone group. The score 4 in Arizona Sexual Experiences Scale (ASEX) scale corresponds to “somewhat difficult,” and the score 5 corresponds to “very difficult,” as an answer to the question “How are you sexually aroused?” One may argue that this small 0.4 difference in score between the two groups, while statistically significant, may not be clinically significant as arousal still ranks as “somewhat difficult” after 1 month of as needed treatment in the absence of any improvement in desire, lubrication, orgasm, or satisfaction.

Finally, Glaser et al studied the use of a testosterone pellet over the course of 12 weeks.29 The study included both pre and postmenopausal women. This study was only observational, and no control group was used. The dosing of the pellet was variable, and it was based on patient weight and investigator judgment. The outcome studied was the change in the menopausal rating scale (MRS). This study was included because a portion of the MRS includes a score for sexual problems. However, the authors did not present the data on how the sexual problem scores changed in premenopausal women from baseline to posttreatment. Rather, they reported the urogenital subgroup score that included sexual problems, bladder problems, and vaginal dryness. The urogenital subgroup score in premenopausal women improved from severe (4.9) problems to mild (1.3). Although this improvement over a 12-week period could be clinically important, it would be ideal to see how each of these individual issues (sexual problems/bladder problems/vaginal dryness) changed over the treatment. It is unclear why the authors grouped them and whether the statistical significance was still noted when the score elements were separated. The authors report that there was some increase in facial hair in some of the women, but they do not specify how common this was. The inclusion of a control group would have been ideal.

To summarize the results of testosterone treatment in premenopausal women, most of the studies are small and show little, if any improvement in libido when compared to placebo.33 Various dosages and routes have been attempted. The longest term study was only 16 weeks, leaving concern for long-term side effects.

Conclusion

To conclude, both limited studies and experiments in nature have shown that libido in women is much more complex than a simple association with testosterone serum levels. In addition, there is a current lack of high-quality, consistent evidence proving that testosterone treatment at low doses is efficacious and safe to help low libido in premenopausal women. Higher doses may be more effective, but this, over time, may carry a risk for hirsutism, clitoral enlargement, deepening of voice, and hair loss.15,16 To reach the level of sexual arousal in men, the testosterone levels likely need to be >300 ng/dL, with masculinization as a result.14 While the studies reviewed have not shown consistent efficacy for testosterone use in premenopausal women, strong advocates for its continued use feel that the findings published so far are due to poorly designed studies. Should high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) be performed on testosterone use in premenopausal women, the findings may be different.

If the primary role for testosterone is not for libido, could testosterone have other important physiological roles in premenopausal females? Some have suggested that testosterone is critical in bone development and maintenance. However, 46XY males with aromatase deficiency have normal to elevated testosterone levels and exhibit increased height, yet they develop osteoporosis.36 Also, men with absent estrogen receptors (who have elevated estrogen levels and normal testosterone levels) are tall and also develop osteoporosis.37 In addition, these men do not respond to estrogen treatment or added testosterone. Based on these studies, the role of testosterone in bone development and maintenance in women is doubtful.

Testosterone therapy may be more efficacious in other subgroups of women such as postmenopausal women. However, the only RCT patch study in postmenopausal women, The Intrinsa (testosterone patch study), showed only approximately one more SSE, and it was not approved by the FDA in 2004 for this indication. It was turned down for insufficient response and because no long-term safety data were investigated.

So, if the direct action of testosterone on the testosterone receptor is not the primary factor related to libido, what are the other possible mechanisms? Some have suggested that the important step is when testosterone is aromatized to estrogen. Perhaps estrogen is more important for libido, and any prior associations with testosterone were due to the fact that it can be a precursor for estradiol. For example, a large study found that men on testosterone treatment with low libido had statistically significantly lower estradiol levels.38 A study on castrated, testosterone-treated Japanese quail showed that the injection of an aromatase inhibitor (which results in high testosterone levels, but low estradiol levels) completely suppressed appetitive sexual behavior.39

While avoiding the use of testosterone in premenopausal women limits the pharmacologic options for low libido even further, the limited choice may not justify using a medication that has not been shown to be consistently effective and safe. For those who are strong advocates for testosterone use in premenopausal women, consideration should be made to scientifically study the treatment using a randomized controlled trial. In the absence of any other pharmacologic interventions, exercise, stress reduction, and couples counseling are reasonable adjuncts for premenopausal women with low libido.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970–978. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181898cdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canup R, Bogenberger K, Attipoe S, et al. Trends in androgen prescriptions from military treatment facilities: 2007 to 2011. Mil Med. 2015;180(7):728–731. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-14-00496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carr BR. The ovary and the normal menstrual cycle. In: Carr BR, Blackwell RE, Azziz R, editors. Essential Reproductive Medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004. pp. 61–101. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson JD, Foster DW, Kronenberg HM, Larsen PR. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr BR. Becker K. Principles and Practice of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: J.B. Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2001. The maternal-fetal-placental unit; pp. 1059–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horton R, Romanoff E, Walker J. Androstenedione and testosterone in ovarian venous and peripheral plasma during ovariectomy for breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1966;26(11):1267–1269. doi: 10.1210/jcem-26-11-1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Word RA, Fesmire S, Carr BR, Rainey WE. Human ovarian expression of 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase types 1, 2, and 3. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(10):3594–3598. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Expected Values & S.I. Unit Conversion Tables. Esoterix, Inc.; [Accessed July 15, 2016]. Available from: www.esoterix.com. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabriel Tobia WWI. DSM-5 changes in diagnostic criteria of sexual dysfunctions. Reprod Syst Sex Disord. 2013;02(02):2–4. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burger HG, Papalia M-A. A clinical update on female androgen insufficiency – testosterone testing and treatment in women presenting with low sexual desire. Sex Health. 2006;3(2):73–78. doi: 10.1071/sh05055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison SL, Bell R, Donath S, Montalto JG, Davis SR. Androgen levels in adult females: changes with age, menopause, and oophorectomy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(7):3847–3853. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2536–2559. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang G, Pencina KM, Coady JA, Beleva YM, Bhasin S, Basaria S. Functional voice testing detects early changes in vocal pitch in women during testosterone administration. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2254–2260. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaltsas GA, Mukherjee JJ, Kola B, et al. Is ovarian and adrenal venous catheterization and sampling helpful in the investigation of hyperandrogenic women? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2003;59(1):34–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.2003.01792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantzoros CS, Georgiadis EI, Trichopoulos D, Mantzoros C. Contribution of dihydrotestosterone to male sexual behaviour resident in medicine. BMJ. 1995;310(6990):1289–1291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6990.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nyunt A, Stephen G, Gibbin J, et al. Androgen status in healthy premenopausal women with loss of libido. J Sex Marital Ther. 2010;31(1):73–80. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elsenbruch S, Hahn S, Kowalsky D, et al. Quality of life, psychosocial well-being, and sexual satisfaction in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5801–5807. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caruso S, Rugolo S, Agnello C, Romano M, Cianci A. Quality of sexual life in hyperandrogenic women treated with an oral contraceptive containing chlormadinone acetate. J Sex Med. 2009;6(12):3376–3384. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pastor Z, Holla K, Chmel R. The influence of combined oral contraceptives on female sexual desire: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;18(1):27–43. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2012.728643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wisniewsky AB, Migeon CJ, Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Gearhart JP, Berkovitz GD, Money J. Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome: long-term medical, surgical, and psychosexual outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(8):2664–2669. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.8.6742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wåhlin-Jacobsen S, Pedersen Anette Tønn, Wåhlin-Jacobsen S, et al. Is there a correlation between androgens and sexual desire in women? J Sex Med. 2015;12(2):358–373. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basson R, Brotto LA, Petkau AJ, Labrie F. Role of androgens in women’s sexual dysfunction. Menopause. 2010;17(5):962–971. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181d59765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alder J, Zanetti R, Wight E, Urech C, Fink N, Bitzer J. Sexual dysfunction after premenopausal stage I and II breast cancer: do androgens play a role? J Sex Med. 2008;5(8):1898–1906. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.00893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riley A. Controlled studies on women presen ting with sexual drive disorder: I endocrine status. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(3):269–283. doi: 10.1080/00926230050084669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell R. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294(1):91–96. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nyunt A, Stephen G, Gibbin J, et al. Androgen status in healthy premenopausal women with loss of libido. J Sex Marital Ther. 2005;31(1):73–80. doi: 10.1080/00926230590475314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glaser R, York AE, Dimitrakakis C. Beneficial effects of testosterone therapy in women measured by the validated Menopause Rating Scale (MRS) Maturitas. 2011;68(4):355–361. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elaut E, De Cuypere G, De Sutter P, et al. Hypoactive sexual desire in transsexual women: prevalence and association with testosterone levels. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158(3):393–399. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turna B, Apaydin E, Semerci B, Altay B, Cikili N, Nazli O. Women with low libido: correlation of decreased androgen levels with female sexual function index. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(2):148–153. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Santoro N, Torrens J, Crawford S, et al. Correlates of circulating androgens in mid-life women: the study of women’s health across the nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4836–4845. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davis S, Papalia MA, Norman RJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone metered-dose transdermal spray for treating decreased sexual satisfaction in premenopausal women. Annu Intern Med. 2008;148:569–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-8-200804150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, Wolfe R, Davis SR. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves well-being, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10(5):390–398. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000060256.03945.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chudakov B, Ben Zion IZ, Belmaker RH. Transdermal testosterone gel PRN application for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: a controlled pilot study of the effects on the arizona sexual experiences scale for females and sexual function questionnaire. J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):204–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bulun SE. Aromatase and estrogen receptor α deficiency. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(2):323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bulun SE. Aromatase deficiency and estrogen resistance: from molecular genetics to clinic. Semin Reprod Med. 2000;18(1):31–39. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-13481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan RS, Cook KR, Reilly WG. High estrogen in men after injectable testosterone therapy: the low T experience. Am J Mens Health. 2015;9(3):229–234. doi: 10.1177/1557988314539000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balthazart J, Castagna C, Ball GF. Aromatase inhibition blocks the activation and sexual differentiation of appetitive male sexual behavior in Japanese quail. Behav Neurosci. 1997;111(2):381–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]