Abstract

Background

COPD-related deaths are increasing in Japan, with ~5.3 million people at risk.

Methods

The SHINE was a 26-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study that evaluated safety and efficacy of indacaterol (IND)/glycopyrronium (GLY) 110/50 μg once daily (od) compared with GLY 50 μg od, IND 150 μg od, open-label tiotropium (TIO) 18 μg od, and placebo. The primary end point was trough forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) at Week 26. Other key end points included peak FEV1, area under the curve for FEV1 from 5 minutes to 4 hours (FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h), Transition Dyspnea Index focal score, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score, and safety. Here, we present efficacy and safety of IND/GLY in the Japanese subgroup.

Results

Of 2,144 patients from the SHINE study, 182 (8.5%) were Japanese and randomized to IND/GLY (n=42), IND (n=41), GLY (n=40), TIO (n=40), or placebo (n=19). Improvement in trough FEV1 from baseline was 190 mL with IND/GLY and treatment differences versus IND (90 mL), GLY (100 mL), TIO (90 mL), and placebo (280 mL) along with a rapid onset of action at Week 26. IND/GLY showed an improvement in FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h versus all comparators (all P<0.05). All the treatments were well tolerated and showed comparable effect on Transition Dyspnea Index focal score and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire total score. The effect of IND/GLY in the Japanese subgroup was consistent to overall SHINE study population.

Conclusion

IND/GLY demonstrated superior efficacy and comparable safety compared with its monocomponents, open-label TIO, and placebo and may be used as a treatment option for the management of moderate-to-severe COPD in Japanese patients.

Keywords: SHINE study, Japanese subgroup, COPD, indacaterol/glycopyrronium, open-label tiotropium

Introduction

COPD was the tenth most common cause of disease-related deaths in Japan in 2014, and it was found that the number of COPD-related deaths is increasing.1 An epidemiological survey in Japanese population revealed that the prevalence of physician-diagnosed COPD in Japan is increasing, and ~8.6% of the patients aged ≥40 years are suffering from COPD. An estimated population of 5.3 million Japanese are now at risk of developing COPD; however, only a small proportion (9.4%) were diagnosed to have COPD.2,3

Decline in quality of life due to breathlessness is the major challenge in the management of COPD that demands sustained improvement in lung function.4 Long-acting bronchodilators of different pharmacological classes, either as monotherapy or in combination, are now the preferred choice and proven cornerstone for treating compromised airflow in patients with COPD.4 In situations where a single bronchodilator fails to provide the desired effect, both Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) strategy and Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS) guidelines recommend the use of a fixed-dose combination of a long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) and a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) for management of symptomatic patients with COPD.4,5 A fixed-dose LABA/LAMA combination, indacaterol (IND)/glycopyrronium (GLY), was evaluated in 14 controlled trials as maintenance treatment for patients with COPD. Outcomes of these studies demonstrated better efficacy of IND/GLY in terms of improving lung function and quality of life, with a comparable safety profile versus placebo,6–8 LAMA, open-label tiotropium (TIO),9 and a combination of LABA/inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and salmeterol/fluticasone (50/500 μg) in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD. Most of these trials have been conducted in Caucasian patients; however, two studies, SHINE and ARISE, evaluated the efficacy of IND/GLY in a Japanese patient subgroup as well.10,11 In the overall population of the SHINE study, IND/GLY showed superior improvements in lung function and health status compared with placebo, IND, GLY, and open-label TIO with a similar safety profile in patients with COPD.10 Here, we report the efficacy and safety of IND/GLY in the Japanese subgroup of patients from the SHINE study.

Methods

SHINE was a 26-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo- and active-controlled study (www.ClinicalTrial.gov identifier NCT01202188).10 After the eligibility assessments, patients were randomized (2:2:2:2:1) to receive once daily (od) IND/GLY 110/50 μg, IND 150 μg, GLY 50 μg, open-label TIO 18 μg, or matching placebo. IND/GLY, IND, GLY, and placebo were administered via the Breezhaler® device, whereas TIO was delivered via the HandiHaler® device. Men and women aged ≥40 years with moderate-to-severe stable COPD and a smoking history of ≥10 pack-years who had a postbronchodilator forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) ≥30% and <80% of predicted normal value and a postbronchodilator FEV1/forced vital capacity ratio <0.70 were included in the study. The key exclusion criterion was COPD exacerbation that required treatment with antibiotics, systemic steroids (oral or intravenous), or hospitalization during 6 weeks prior to screening or before randomization. During the study, salbutamol/albuterol was permitted as a rescue medication. Informed consent was taken from all the eligible patients. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all applicable regulatory requirements and was approved by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Japan, as well as all relevant national and local ethics review boards (Table S1).

Assessments

The primary end point of the study was trough FEV1 (mean of FEV1 values measured at 23 hours 15 minutes and 23 hours 45 minutes) after IND/GLY administration at Week 26 versus IND and GLY. Other key end points included peak FEV1, area under the curve for FEV1 from 5 minutes to 4 hours (FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h), and trough FEV1 throughout the study period. Nonspirometric analysis included the Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) focal score and St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score at Week 26. Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs) and serious AEs over the 26-week study period.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using a linear mixed model, which included FEV1 as the dependent variable, treatment as an fixed effect, the variables (FEV1, ICS use, FEV1 reversibility components, and smoking status) at baseline as covariates, and centre as a random effect. The estimated treatment differences were presented as least-squares mean with standard errors and the associated 95% confidence interval. The secondary efficacy variables, which included peak FEV1, FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h, trough FEV1 over 26 weeks, TDI focal score, and SGRQ total score, were also analyzed using the same mixed model as specified for the analysis of the primary variable, with the appropriate baseline measurement included as a covariate.10 In addition, the proportions of patients who achieved a clinically important improvement in the SGRQ and TDI focal score were analyzed using logistic regression as specified for the analysis of the primary variable, with the appropriate baseline measurement included as a covariate.

Results

Patient characteristics

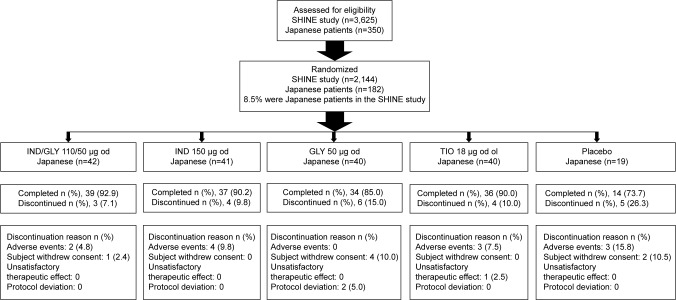

Of the total 2,144 patients randomized in the SHINE study, 182 (8.5%) were Japanese and randomized to receive IND/GLY 110/50 μg (n=42), IND 110 μg (n=41), GLY 50 μg (n=40), open-label TIO 18 μg (n=40), and matching placebo (n=19). The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were comparable across all the groups (Table 1). More than 90% of the patients in the Japanese cohort were men aged >68 years, and their mean percentage of predicted postbronchodilator FEV1 was ~60%, with only 19% reversibility of FEV1 after bronchodilation. More than 75% of patients had moderate-to-severe COPD according to the GOLD 2009 guidelines, and almost 10% of patients in the Japanese subgroup were having a history of COPD exacerbation in the previous year and ~25% were using ICS at baseline. In total, 160 patients (87.9%) completed the study; the major reasons for discontinuation from the study were AEs and withdrawal of consent by the patients (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics of the Japanese subgroup

| IND/GLY (n=42) | IND (n=41) | GLY (n=40) | TIO* (n=40) | Placebo (n=19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 71.0 (6.92) | 69.2 (5.96) | 69.0 (8.87) | 67.8 (9.25) | 68.9 (5.22) |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 42 (100) | 40 (97.6) | 38 (95.0) | 37 (92.5) | 18 (94.7) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 22.4 (3.35) | 22.7 (3.17) | 22.2 (3.05) | 22.8 (3.54) | 24.3 (1.86) |

| Smoking history, pack-years | 64.7 (25.21) | 59.9 (27.71) | 69.8 (33.36) | 64.7 (38.25) | 52.3 (20.20) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |||||

| Ex-smoker | 31 (73.8) | 31 (75.6) | 31 (77.5) | 29 (72.5) | 17 (89.5) |

| Current smoker | 11 (26.2) | 10 (24.4) | 9 (22.5) | 11 (27.5) | 2 (10.5) |

| ICS use at baseline, n (%) | |||||

| No | 31 (73.8) | 30 (73.2) | 28 (70.0) | 29 (72.5) | 14 (73.7) |

| Yes | 11 (26.2) | 11 (26.8) | 12 (30.0) | 11 (27.5) | 5 (26.3) |

| Number of COPD exacerbations in the previous year, n (%) | |||||

| 0 | 39 (92.9) | 32 (78.0) | 31 (77.5) | 33 (82.5) | 17 (89.5) |

| 1 | 2 (4.8) | 9 (22.0) | 8 (20.0) | 7 (17.5) | 1 (5.3) |

| ≥2 | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 1 (5.3) |

| Severity of COPD (GOLD 2008), n (%) | |||||

| Moderate COPD | 32 (76.2) | 31 (75.6) | 35 (87.5) | 28 (70.0) | 14 (73.7) |

| Severe COPD | 10 (23.8) | 10 (24.4) | 4 (10.0) | 12 (30.0) | 5 (26.3) |

| Duration of COPD, years | 3.6 (3.23) | 3.9 (5.01) | 4.0 (3.80) | 3.4 (2.10) | 3.2 (2.78) |

| FEV1, prebronchodilator, L | 1.36 (0.44) | 1.32 (0.43) | 1.35 (0.41) | 1.22 (0.42) | 1.27 (0.38) |

| FEV1, postbronchodilator, L | 1.60 (0.42) | 1.54 (0.46) | 1.56 (0.42) | 1.48 (0.45) | 1.47 (0.46) |

| FEV1 (L) postbronchodilator (% predicted FEV1) | 61.357 (13.0941) | 60.268 (14.8594) | 61.300 (11.4672) | 57.600 (12.8797) | 57.474 (13.1376) |

| FEV1 reversibility after inhalation of bronchodilator (%) | 20.167 (13.3543) | 18.829 (13.6874) | 17.000 (12.7481) | 23.800 (15.4026) | 15.737 (9.4331) |

Note: Data are represented as mean (standard deviation) unless otherwise specified.

Open label.

Abbreviations: IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; TIO, tiotropium; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; GOLD, Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease.

Figure 1.

Patient disposition.

Note: n, number of patients.

Abbreviations: IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; od, once daily; TIO, tiotropium; ol, open label.

Lung function

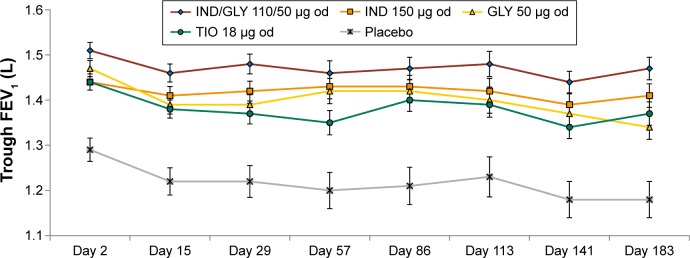

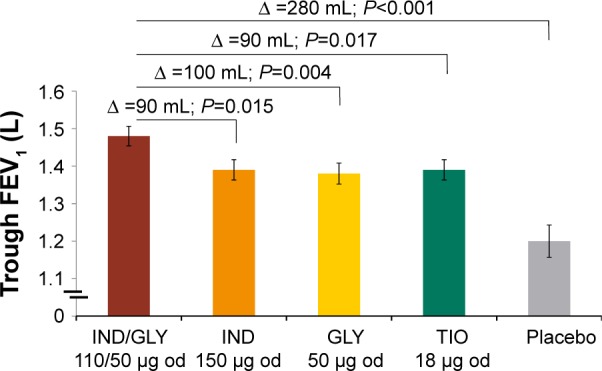

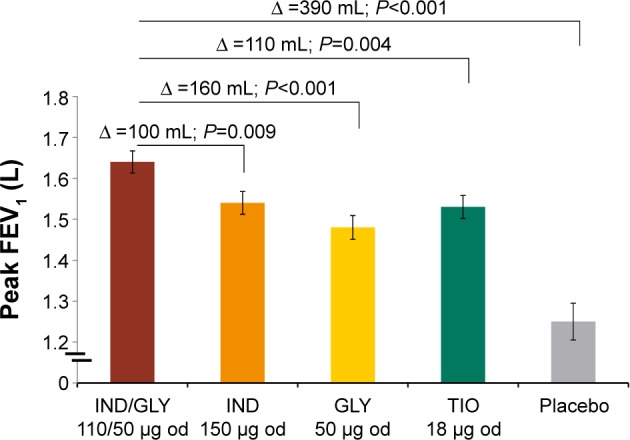

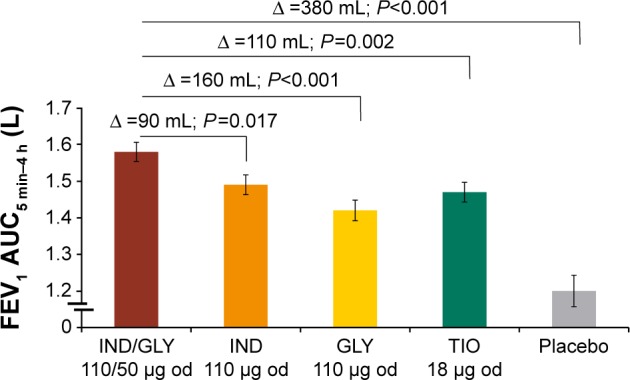

The primary efficacy end point of the SHINE study was achieving a 190 mL improvement in trough FEV1 from baseline with IND/GLY in Japanese patients. Improvement in lung function was greater in Japanese patients treated using IND/GLY compared with IND (90 mL), GLY (100 mL), TIO (90 mL), and placebo (280 mL; Figure 2).10 The spirometric profile in terms of trough FEV1 with IND/GLY was superior compared with TIO and placebo on Day 2 and Week 26, with treatment differences ranging from 90 mL to 290 mL (Figure 3). IND/GLY showed greater improvements in peak FEV1 from 5 minutes to 4 hours compared with IND, GLY, TIO, and placebo at Week 26, with treatment differences ranging from 100 mL to 390 mL (all P<0.01; Figure 4). In addition, an improvement in lung function was also observed with IND/GLY in terms of FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h compared with IND, GLY, TIO, and placebo, at the end of study, with treatment differences ranging from 90 mL to 380 mL (all P<0.05; Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Trough FEV1 (L) after 26 weeks in the Japanese subgroup.

Notes: Data are presented as LSM (standard error). Trough FEV1 is defined as the average of the post dose 23 hours 15 minutes and 23 hours 45 minutes FEV1 values (excluding values taken outside 22 hours 45 minutes and 24 hours 15 minutes post dose) at Day 2.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LSM, least-squares mean; IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; od, once daily; TIO, tiotropium; ∆, treatment difference.

Figure 3.

Trough FEV1 (L) over 26 weeks in the Japanese subgroup.

Note: Data are presented as LSM (standard error).

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LSM, least-squares mean; IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; od, once daily; TIO, tiotropium.

Figure 4.

Peak FEV1 (L) from 5 minutes to 4 hours at Week 26 in the Japanese subgroup.

Notes: Data are presented as LSM (standard error). Peak FEV1 is defined as the maximum FEV1 during the first 4 hours after dosing.

Abbreviations: FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LSM, least-squares mean; IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; od, once daily; TIO, tiotropium; ∆, treatment difference.

Figure 5.

FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h (L) at Week 26 in the Japanese subgroup.

Note: Data are presented as LSM (standard error).

Abbreviations: FEV1 AUC5 min-4 h, area under the curve for FEV1 from 5 minutes to 4 hours; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; LSM, least-squares mean; IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; od, once daily; TIO, tiotropium; ∆, treatment difference.

Patient-reported outcomes

Dyspnea control in terms of improvement in TDI focal score in the Japanese subgroup was comparable across all treatment groups. Treatment differences between IND/GLY versus placebo were 0.67 units and versus IND, GLY, TIO were 0.69 units, 0.03 units, and 0.65 units, respectively. A higher proportion of patients achieved a clinically meaningful improvement in the TDI focal score (≥1 unit) with IND/GLY versus IND (odds ratio [OR], 1.60), GLY (OR, 1.01), TIO (OR, 1.16), and placebo (OR, 1.15).

Improvement in health status assessed via reduction in the SGRQ total score was similar across all treatment groups in the Japanese patient subgroup. Treatment differences in the SGRQ total score between IND/GLY vs placebo, IND, GLY, and TIO were −1.31 units, −0.48 units, −3.75 units, and −0.96 units, respectively. The proportion of patients achieving a clinically meaningful improvement in the SGRQ total score (≥4-unit reduction) was highest with IND/GLY compared to IND (OR, 1.69), GLY (OR, 3.13), TIO (OR, 2.36), and placebo (OR, 0.86).

Safety

The overall incidence of AEs was similar across the five treatment groups, and the lowest incidence was reported for patients treated with IND/GLY (21 (50%); IND, 27 (65.9%); GLY, 24 (60.0%); TIO, 31 (77.5%); and placebo, 12 (63.2%); Table 2). COPD exacerbations were found to be the frequent AEs in all treatment groups, with their lowest occurrence in patients treated with IND/GLY (~12%). Serious AEs were comparable across all treatment groups. Moreover, no cardiovascular AEs, major adverse cardiac events, cerebro–cardiovascular AEs, abnormal changes from baseline QTc in resting ECG was obtained using Bazett’s formula (QTcB), Fridericia’s formula (QTcF) (<10 mlliseconds) or heart rate, or imbalance in hematocrit values was observed in the Japanese subgroup.

Table 2.

Summary of AEs and SAEs by preferred terms in the Japanese subgroup

| IND/GLY (n=42) | IND (n=41) | GLY (n=40) | TIO (n=40) | Placebo (n=19) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total AEs | 21 (50.0) | 27 (65.9) | 24 (60.0) | 31 (77.5) | 12 (63.2) |

| AEs ≥2 incidences in any group | |||||

| COPDa | 5 (11.9) | 7 (17.1) | 6 (15.0) | 10 (25.0) | 6 (31.6) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 4 (9.5) | 10 (24.4) | 9 (22.5) | 9 (22.5) | 5 (26.3) |

| Cough | 2 (4.8) | 2 (4.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Productive cough | 2 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 2 (4.8) | 2 (4.9) | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Bronchitis | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.5) | 1 (5.3) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 2 (5.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| GERD | 0 | 2 (4.9) | 1 (2.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Back pain | 0 | 0 | 3 (7.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Drug-related AEs | 7 (16.7) | 5 (12.2) | 4 (10.0) | 5 (12.5) | 0 |

| AEs leading to permanent discontinuation of study drugs | |||||

| Total SAEs | 1 (2.4) | 5 (12.2) | 2 (5.0) | 1 (2.5) | 2 (10.5) |

Notes: Data are presented as number of patients (percentage).

Includes COPD exacerbation or COPD worsening.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; SAEs, serious adverse events; IND, indacaterol; GLY, glycopyrronium; TIO, tiotropium; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Discussion

The aim of this post hoc analysis was to explore the efficacy and safety profile of IND/GLY in the Japanese subgroup of the SHINE study. Based on the overall results of the SHINE study, the efficacy of IND/GLY was superior to that of placebo, with comparable safety.10 The results of this analysis support our claim that IND/GLY improves lung function and health status in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD with compromised airflow according to the GOLD guidelines, irrespective of ethnicity. The fourth edition of the JRS guidelines, which is customized for the Japanese scenario, recommend LAMA/LABA for the management of moderate-to-severe COPD with symptoms and the use of ICS in combination with LABA or LAMA only if the condition does not improve.4,5,12 GOLD strategy that considers diverse ethnicity as well as various COPD phenotypes differs from the JRS guidelines, which are specific for the Japanese population, in terms of prescribing ICS.4,5 The difference in the recommendations may be due to the fact that Japanese patients with COPD experience fewer COPD exacerbations compared to Caucasians.12 In the Japanese subgroup of the SHINE study, we observed greater improvements in lung function with IND/GLY versus IND, GLY, and TIO mono-therapies, although the improvement in quality of life was comparable across all groups. The results of this subgroup analysis were similar to those observed in the entire study population.10 The small sample size is perhaps responsible for the lower baseline FEV1 observed in the TIO group (1.22 L) than the IND/GLY group (1.36 L), which was at least partially responsible for the 90 mL “treatment effect” of IND/GLY versus TIO at the end of 26 weeks. However, baseline FEV1 was used as a covariate in the statistical analysis, and the treatment effect was adjusted to account for the baseline difference in FEV1 between the IND/GLY and TIO groups. The aforementioned findings were similar to those reported in another study, wherein baseline FEV1 affected the treatment efficacy of a bronchodilator, which showed a smaller change from baseline FEV1 value in patients with lower baseline FEV1.13 In addition to the observed improvements in trough FEV1, our study also demonstrated rapid bronchodilation with IND/GLY in terms of FEV1 AUC5 min–4 h compared to the monotherapy components, TIO, and placebo. In previous studies, spirometric outcomes of IND/GLY treatment showed a comparable reduction in the rate of COPD exacerbations, along with superior improvement in lung function versus its monotherapy components, TIO, and salmeterol/fluticasone and without considerable variations in the TDI focal score and SGRQ total score among different treatment groups.9,11,14,15 In our study, the results of the Japanese subgroup analysis showed comparable improvements in the TDI focal score and SGRQ total score, which is consistent with the results of a previous study.14 A higher proportion of patients from the IND/GLY group achieved minimal clinically important differences for TDI and SGRQ compared with the other treatment groups. Moreover, the number of patients in the Japanese subgroup was small to determine the significant improvement in the TDI focal score and SGRQ total score.

The SHINE study demonstrated that safety profile of IND/GLY in Japanese patients with COPD was consistent with the overall study population.10 The most frequently reported AE was COPD exacerbation in the Japanese subgroup, and the occurrence was ~12%, which was lower compared with TIO (25%) and placebo (~32%). Furthermore, the incidents of exacerbations were lesser in the Japanese subgroup than the overall study population, where ~39% exacerbations were reported. This fact was supported by the results of a previous study that demonstrated that IND/GLY was superior in preventing moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbations compared with TIO, with concomitant improvements in lung function and health status.9 A pooled analysis of 14 randomized clinical trials with data from 11,404 patients with COPD demonstrated that IND/GLY did not increase the risk of investigated safety end points and had a comparable safety profile as its monocomponents, TIO, and placebo.16

Conclusion

Based on the results of this subgroup analysis, we can conclude that the efficacy and safety of IND/GLY in the Japanese population were similar to that in the overall study population of the SHINE study; thus, IND/GLY may be considered as a treatment option for the management of Japanese patients with moderate-to-severe COPD.

Supplementary material

Table S1.

List of relevant national and local ethics review boards

| 1. | United States: Food and Drug Administration |

| 2. | Argentina: Administracion Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y TecnologiaMedica |

| 3. | Argentina: Human Research Bioethics Committee |

| 4. | Argentina: Ministry of Health |

| 5. | Australia: Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration |

| 6. | Australia: Human Research Ethics Committee |

| 7. | Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council |

| 8. | Bulgaria: Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 9. | Bulgaria: Ministry of Health |

| 10. | Canada: Health Canada |

| 11. | China: Food and Drug Administration |

| 12. | Finland: Ethics Committee |

| 13. | Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health |

| 14. | Finland: Finnish Medicines Agency |

| 15. | France: Afssaps - Agencefrançaise de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé (Saint-Denis) |

| 16. | France: Direction Générale de la Santé |

| 17. | France: French Data Protection Authority |

| 18. | France: Haute Autorité de Santé Transparency Commission |

| 19. | France: Institutional Ethical Committee |

| 20. | France: Ministry of Health |

| 21. | France: National Consultative Ethics Committee for Health and Life Sciences |

| 22. | Germany: Ethics Commission |

| 23. | Germany: Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices |

| 24. | Germany: Federal Ministry of Education and Research |

| 25. | Germany: Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection |

| 26. | Germany: German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information |

| 27. | Germany: Ministry of Health |

| 28. | Germany: Paul-Ehrlich-Institut |

| 29. | Guatemala: MSPAS - Ministerio de SaludPública y Asistencia Social: Programa Nacional de Farmacovigilancia |

| 30. | Hungary: Research Ethics Medical Committee |

| 31. | Hungary: National Institute of Pharmacy |

| 32. | India: Central Drugs Standard Control Organization |

| 33. | India: Department of Atomic Energy |

| 34. | India: Drugs Controller General of India |

| 35. | India: Indian Council of Medical Research |

| 36. | India: Institutional Review Board |

| 37. | India: Ministry of Health |

| 38. | India: Ministry of Science and Technology |

| 39. | India: Science and Engineering Research Council |

| 40. | Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare |

| 41. | Mexico: Ethics Committee |

| 42. | Mexico: Federal Commission for Protection Against Health Risks |

| 43. | Mexico: Federal Commission for Sanitary Risks Protection |

| 44. | Mexico: Ministry of Health |

| 45. | Mexico: National Council of Science and Technology |

| 46. | Mexico: National Institute of Public Health, Health Secretariat |

| 47. | The Netherlands: Independent Ethics Committee |

| 48. | The Netherlands: Dutch Health Care Inspectorate |

| 49. | The Netherlands: Medical Ethics Review Committee (METC) |

| 50. | The Netherlands: Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB) |

| 51. | The Netherlands: The Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) |

| 52. | Panama: Ministry of Health |

| 53. | Philippines: Department of Health |

| 54. | Philippines: Bureau of Food and Drugs |

| 55. | Poland: Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products |

| 56. | Poland: Ministry of Health |

| 57. | Poland: Ministry of Science and Higher Education |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank their colleagues who were involved in the planning, execution, and analysis of the SHINE study and all the study participants. This study was sponsored by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. The authors were assisted in the preparation of this manuscript by Kevin Roche and Santanu Bhadra of Novartis Healthcare Pvt. Ltd., Hyderabad, India.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

SH had received grants and/or lecture fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca K.K., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., GlaxoSmithKline K.K., KYORIN Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Nippon Boehringer Ingelheim Co. Ltd., Torii Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., and Novartis Pharma K.K. within the last 3 years. SM, TK, KI, and DB are employees of the study sponsor Novartis. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Vital Statistics, Ministry of Health, Labor Welfare Japan 2014. [Accessed December 12, 2015]. Available from: http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/new-info/

- 2.Fukuchi Y, Fernandez L, Kuo HP, et al. Efficacy of tiotropium in COPD patients from Asia: a subgroup analysis from the UPLIFT trial. Respirology. 2011;16(5):825–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.01982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa N, Hattori N, Kohno N, Kobayashi A, Hayamizu T, Johnson M. Airway inflammation in Japanese COPD patients compared with smoking and nonsmoking controls. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:185–192. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S74557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD 2016) [Accessed January 6, 2016]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com.

- 5.Japanese Respiratory Society . Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of COPD. 4th edition. Japanese Respiratory Society; 2013. [Accessed December 12, 2015]. Available from: https://www.jrs.or.jp/modules/guidelines/index.php?content_id=1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beeh KM, Korn S, Beier J, et al. Effect of QVA149 on lung volumes and exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the BRIGHT study. Respir Med. 2014;108(4):584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahl R, Chapman KR, Rudolf M, et al. Safety and efficacy of dual bronchodilation with QVA149 in COPD patients: the ENLIGHTEN study. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1558–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahler DA, Decramer M, D’Urzo A, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 reduces patient-reported dyspnoea in COPD: the BLAZE study. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(6):1599–1609. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00124013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wedzicha JA, Decramer M, Ficker JH, et al. Analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bateman ED, Ferguson GT, Barnes N, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(6):1484–1494. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00200212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asai K, Minakata Y, Hirata K, et al. QVA149 once-daily is safe and well tolerated and improves lung function and health status in Japanese patients with COPD: The ARISE study; European Respiratory Society Annual Congress 2013; Barcelona, Spain. 2013. p. P3392. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horita N, Kaneko T. Role of combined indacaterol and glycopyrronium bromide (QVA149) for the treatment of COPD in Japan. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:813–822. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S56067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calverley P, Pauwels RA, Jones PW, Anderson JA, Vestbos J. The severity of airways obstruction as a determinant of treatment response in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1(3):209–218. doi: 10.2147/copd.2006.1.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelmeier CF, Bateman ED, Pallante J, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily QVA149 compared with twice-daily salmeterol-fluticasone in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ILLUMINATE): a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study. Lancet Respir Med. 2013;1(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhong N, Wang C, Zhou X, et al. LANTERN Investigators LANTERN: a randomized study of QVA149 versus salmeterol/fluticasone combination in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1015–1026. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S84436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wedzicha JA, Dahl R, Buhl R, et al. Pooled safety analysis of the fixed-dose combination of indacaterol and glycopyrronium (QVA149), its monocomponents, and tiotropium versus placebo in COPD patients. Respir Med. 2014;108(10):1498–1507. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

List of relevant national and local ethics review boards

| 1. | United States: Food and Drug Administration |

| 2. | Argentina: Administracion Nacional de Medicamentos, Alimentos y TecnologiaMedica |

| 3. | Argentina: Human Research Bioethics Committee |

| 4. | Argentina: Ministry of Health |

| 5. | Australia: Department of Health and Ageing Therapeutic Goods Administration |

| 6. | Australia: Human Research Ethics Committee |

| 7. | Australia: National Health and Medical Research Council |

| 8. | Bulgaria: Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 9. | Bulgaria: Ministry of Health |

| 10. | Canada: Health Canada |

| 11. | China: Food and Drug Administration |

| 12. | Finland: Ethics Committee |

| 13. | Finland: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health |

| 14. | Finland: Finnish Medicines Agency |

| 15. | France: Afssaps - Agencefrançaise de sécurité sanitaire des produits de santé (Saint-Denis) |

| 16. | France: Direction Générale de la Santé |

| 17. | France: French Data Protection Authority |

| 18. | France: Haute Autorité de Santé Transparency Commission |

| 19. | France: Institutional Ethical Committee |

| 20. | France: Ministry of Health |

| 21. | France: National Consultative Ethics Committee for Health and Life Sciences |

| 22. | Germany: Ethics Commission |

| 23. | Germany: Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices |

| 24. | Germany: Federal Ministry of Education and Research |

| 25. | Germany: Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection |

| 26. | Germany: German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information |

| 27. | Germany: Ministry of Health |

| 28. | Germany: Paul-Ehrlich-Institut |

| 29. | Guatemala: MSPAS - Ministerio de SaludPública y Asistencia Social: Programa Nacional de Farmacovigilancia |

| 30. | Hungary: Research Ethics Medical Committee |

| 31. | Hungary: National Institute of Pharmacy |

| 32. | India: Central Drugs Standard Control Organization |

| 33. | India: Department of Atomic Energy |

| 34. | India: Drugs Controller General of India |

| 35. | India: Indian Council of Medical Research |

| 36. | India: Institutional Review Board |

| 37. | India: Ministry of Health |

| 38. | India: Ministry of Science and Technology |

| 39. | India: Science and Engineering Research Council |

| 40. | Japan: Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare |

| 41. | Mexico: Ethics Committee |

| 42. | Mexico: Federal Commission for Protection Against Health Risks |

| 43. | Mexico: Federal Commission for Sanitary Risks Protection |

| 44. | Mexico: Ministry of Health |

| 45. | Mexico: National Council of Science and Technology |

| 46. | Mexico: National Institute of Public Health, Health Secretariat |

| 47. | The Netherlands: Independent Ethics Committee |

| 48. | The Netherlands: Dutch Health Care Inspectorate |

| 49. | The Netherlands: Medical Ethics Review Committee (METC) |

| 50. | The Netherlands: Medicines Evaluation Board (MEB) |

| 51. | The Netherlands: The Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) |

| 52. | Panama: Ministry of Health |

| 53. | Philippines: Department of Health |

| 54. | Philippines: Bureau of Food and Drugs |

| 55. | Poland: Office for Registration of Medicinal Products, Medical Devices and Biocidal Products |

| 56. | Poland: Ministry of Health |

| 57. | Poland: Ministry of Science and Higher Education |