Abstract

Buerger’s disease, also known as thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), is a segmental inflammatory disease affecting small- and medium-sized vessels, which is strongly associated with tobacco use. Although the etiology is still unknown, recent studies suggest an immunopathogenesis. Diagnosis is based on clinical and angiomorphologic criteria, including age, history of smoking, clinical presentation with distal extremity ischemia, and the absence of other risk factors for atherosclerosis, autoimmune disease, hypercoagulable states, or embolic disease. Until now, no causative therapy exists for TAO. The most important therapeutic intervention is smoking cessations and intravenous prostanoid infusions (iloprost). Furthermore, effective analgesia is crucial for the treatment of ischemic and neuropathic pain and might be expanded by spinal cord stimulation. Revascularization procedures do not play a major role in the treatment of TAO due to the distal localization of arterial occlusion. More recently, immunoadsorption has been introduced eliminating vasoconstrictive G-protein-coupled receptor and other autoantibodies. Cell-based therapies and treatment with bosentan were also advocated. Finally, a consequent prevention and treatment of wounds and infections are essential for the prevention of amputations. To achieve better clinical results, integrated care in multidisciplinary and trans-sectoral teams with emphasis on smoking cessation, pain control, wound management, and social care by professionals, social workers, and family members is necessary.

Keywords: Winiwater-Buerger’s disease, Winiwarter–Buerger, thromboangiitis obliterans, immunoadsorption

Introduction

In 1879, Winiwarter,1 a young assistant physician of Theodor Billroth in Vienna, published the clinical course and pathologic examination of a lower limb amputation of a 57-year-old male describing “a peculiar kind of angiitis and endophlebitis with gangrene”. Although this is considered to be the first case report of thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), the disease is currently more exclusively linked to the American surgeon Buerger2, whose systematic work on clinical and pathological aspects of the disease constituted our modern understanding of the disease.

TAO is an inflammatory vascular pathology affecting small- and medium-sized arteries and veins leading to vessel occlusions by the formation of a mononuclear cell-rich thrombus.2 Its etiology is still unknown, but it is inseparably linked to tobacco use. Due to an undulating clinical course, normal vessel segments and different stages of lesions (acute to chronic types) might be found together in the same patient.2

Patients with Buerger’s disease usually present with acute ischemic or infectious acral lesions (ulcers, gangrenes, subungual infections, phlegmonous) and/or thrombophlebitic nodules. Skin discolorations such as Raynaud’s phenomenon, acrocyanosis, or livedo-like pictures are often seen.3–5 Rarely, a nonerosive arthritis might precede ischemia for months or years.6

Epidemiology

Buerger’s disease occurs worldwide and is more prevalent in males, but an increasing prevalence in females has been reported in different countries.7–9 Disease characteristics and prognosis do not differ between males and females.9 In contrast to North America and Western Europe, the Mediterranean, the near and far East, and the Indian subcontinent are high prevalence regions.3–5 Thus, prevalence rates among in-hospital treated patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease were reported to range from 0.5% to 5.6% in Western Europe, 45%–63% in India, and 16%–66% in Korea and Japan.10 In the meanwhile, the formerly often cited extremely high prevalence rate in Ashkenazi Jews was identified as a scientific error as it referred to the response rate of an invitation to participate in a study and did not reflect the true prevalence in this ethnic group.11 Reported prevalence of TAO seems to decline during the past decades due to a decrease in tobacco use or – as others believe – due to an increase in socioeconomic conditions.12–14

Etiologic, pathologic, and pathogenetic aspects

There is a very tight correlation between the manifestation, flaring, and recurrence of Buerger’s disease (no tobacco, no Buerger’s disease).3–5,10 Thus, tobacco must be considered to be the dominant risk factor. Besides potential differences in regional smoking habits, regional and ethnic differences in the prevalence of the disease might point toward a genetic background determining individual susceptibility. Human–leukocyte–antigen-linked factors may play a role; nevertheless, human leukocyte antigen association studies revealed heterogeneous findings.15–18 Published genetic polymorphisms consist of CD14 T7T polymorphism, eNOS gene 894 T/T polymorphism as a protective factor, and MyD88 rrs7744 A-G polymorphism, coding for a Toll-like receptor signaling adaptor.19–22

Chronic infectious disease – especially periodontal disease – was found to be associated with TAO.23,24 On the other hand, in a particular disease group of the disease (ie, low social status and excessive smokers), periodontal disease can be expected to be very high triggering a close correlation, which does not necessarily imply a causative linkage. Nevertheless, smoldering infections such as periodontitis might trigger autoimmune mechanisms and coagulation.24

Signs of endothelial activation and proliferation as well as the presence of immunocompetent cells are seen in acute type lesions. Immunoglobulin and complement deposition as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T-lymphocytes, CD 20+ B-lymphocytes, and S-100-positive dendritic cells were found alongside the lamina elastica interna, which becomes structurally altered but is typically preserved.25–30 Giant cell formation and the appearance of the so-called microabscesses within the mono-nuclear cell-rich thrombus may occur.2

Analysis of cytokine activation in patients with TAO revealed a pattern of elevated pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines.31,32 Various kinds of autoantibodies have been identified in patients with TAO, including anti-endothelial antibodies, antibodies directed against vessel wall structures such as elastin and collagen, anticardiolipin antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies.33–39 More recently, agonistic autoantibodies directed against G-protein-coupled receptors were identified as potentially promoting vasospasm, compromising microcirculation, damaging vessel structures, and inducing proliferative processes.40

Overall, the findings are consistent with the assumption of an immunopathogenesis of TAO. A first model of this new paradigm has recently been published by Ketha and Cooper.41

Social and psychosomatic aspects

Buerger’s disease typically occurs in patients with a low social status.14 Some authors even described a Buerger-type personality with manipulative and autoaggressive tendencies often matched with denial, negligence, or tendencies to minimize their illness, while others even presumed typical morphological characteristics.42,43 However, no systematic work has been performed in this field, and the preliminary results do not allow differentiating between premorbid traits and conditions and psychological consequences of the chronicity and severity of the disease or implications of chronic drug intake such as morphine or opioids in the affected patients.

Diagnostic criteria

Diagnosis is usually based on clinical and angiomorphologic criteria published by Olin et al and Shionoya.13,44 The latter is based on only five criteria and thus easy to remember (Table 1). Combined upper and lower extremity involvement is present in ~20%–25% of the cases.45,46 An isolated affection of only one limb strongly argues against Buerger’s disease.45 Proximal arterial involvement is rarely present.47,48 Nevertheless, case reports of typical lesions even in cerebral, coronary, and visceral arteries have been published.49–53 Thrombophlebitis – if present – is often of migratory type and precedes or parallels arterial disease activity.54

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for TAO

| Disease onset before the age of 50 years |

| Smoking |

| Absence of other atherosclerotic risk factors |

| Infrapopliteal arterial occlusions |

| Upper limb involvement or phlebitis migrans |

Note: Data from Shionoya43

Abbreviation: TAO, thromboangiitis obliterans.

Establishing diagnosis

Typically, a young heavy smoker presents with a more or less symmetrical distal ischemic syndrome or a crural–acral or antebrachial–acral type of arterial occlusion in two or more extremities. Distal pulses are usually absent or diminished, but can be normal in the case of exclusive acral disease manifestations. Allen’s test often reveals an upper extremity involvement.

Ankle brachial index or forearm–brachial index is usually reduced, but might be normal in cases with more distally located disease. Digital pulse recordings are characterized by low amplitudes and delayed slopes, anarchic or silent pulse curves.

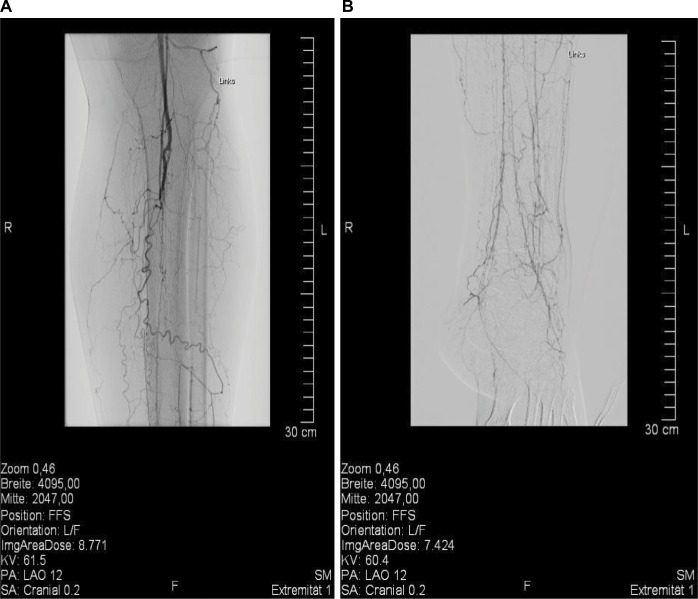

Angiographically, a typical but not pathognomonic pattern (Figure 1) has been described, which substantiates the diagnosis.43 This pattern might also be identified by magnetic resonance imaging or a careful duplex ultrasound examination.

Figure 1.

Angiographic pattern of Buerger’s disease in a young male patient.

Notes: (A) the proximal crural angiography and (B) the distal crural angiography of the same patient. The typical angiographic pattern of TAO consists of smooth vessels without calcifications, vasospasm, distally located multi-segmental vessel occlusions, cutoff occlusions, corkscrew collaterals often combined with the Martorell’s sign (ie, the formation of collateral vessels within the occluded lumen of the affected vessel), and a no-refill phenomenon of the original vessel.42

Abbreviation: TAO, thromboangiitis obliterans.

Embolic disease – if suspected – can be ruled out by transesophageal echocardiography, computer tomography angiography, and duplex ultrasound of the proximal extremity arteries.

Capillary video microscopy is often limited by infection or hornification. It often reveals capillary loss and unspecific morphologic changes.55,56 Nevertheless, capillary microscopy is a useful tool in the differential diagnosis.

There are no specific biomarkers for TAO.3–5,10 Systemic inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein are usually absent or only slightly elevated and are therefore unsuitable for the assessment or monitoring of disease activity. Nevertheless, laboratory tests are important to exclude other entities such as diabetes, connective tissue disease, vasculitides, or congenital or acquired thrombophilia.3–5,10

If biopsy can be performed without endangering the limb or if an amputation is performed, diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathologic examination. Fresh thrombophlebitic nodules are suitable for this purpose.

Therapy

In the past decades, therapeutic efforts concentrated on pain and infection control, revascularization, or amputation.

Smoking cessation

Nevertheless, the most important therapeutic intervention in Buerger’s disease is smoking cessation.3–5,10 Its overwhelming effect for the prevention of consecutive limb amputation was impressively shown.13 Patients with TAO should be prevented not only from active smoking but also from alternative consumption mode and passive exposure.57,58 Tobacco dependency is usually considered to be exceptionally strong in patients with Buerger’s disease, but in the only prospective study addressing this question the degree of tobacco dependence was similar to that in patients with coronary artery disease.59

Individual strategies for smoking withdrawal have to be discussed, including in- and outpatient treatment in specialized institutions with multidisciplinary teams.60,61 Unfortunately, the percentage of patients who maintain smoking cessation despite is low.60,61 In one study, the continuous abstinence rate decreased from 29% at the end of the treatment to 18.5% at the 12-month follow-up.61 Best results seem to be achieved by structured and guided peer group and anti-smoking programs starting during hospital stay or shortly thereafter.62,63 Medication support by nicotine replacement therapy, bupropion, or varenicline might be provided. Whether replacement therapies or adjuvant therapies might prolong disease activity was – to our knowledge – not addressed, but should be examined in further studies.

As was shown by the TEMPO study, work and family circumstances, co-occurring substance use, and psychological difficulties may influence smoking cessation in the typical age groups of patients with Buerger’s disease. Factors specifically associated with a low probability of smoking cessation were job strain and symptoms of hyperactivity/inattention, while occupational grade was associated with smoking relapse.64

Prostanoid therapy and antiplatelet drugs

The effectiveness of prostanoid therapy was elucidated in two older randomized trials and in two more recently published trials prospectively assessing clinical outcome in addition to smoking cessation, aspirin, or compared with sympathectomy.65–68 Iloprost, a prostacyclin analog, is considered the drug of choice.65 Fiessinger and Schäfer65 randomly allocated 152 patients with Buerger’s disease and pain from critical leg ischemia to iloprost intravenously or low-dose aspirin for 28 days in a double-blind trial. Fifty-eight (85%) of 68 iloprost-treated patients showed ulcer healing or relief of ischemic pain versus eleven (17%) of 65 in the aspirin-treated group. Forty-three (63%) patients on iloprost treatment had complete relief of pain, compared with 18 (28%) on aspirin. Unfortunately, these striking results could not reproduced in the largest randomized trial, including 319 patients, when iloprost was administered orally in two dose regimes and compared with placebo.66 In a study published by the Turkish Buerger’s Disease Research Group, complete ulcer healing rate was 61.9% in those receiving iloprost and 41% in the lumbar sympathectomy group at 4 weeks and 85.3% versus 52.3% at 24 weeks.67 In a prospective Turkish multicenter observational trial in 158 patients with Buerger’s disease suffering from rest pain and/or ischemic lesions, complete ulcer healing without residual rest pain or major amputation was met by 60% of the patients treated with iloprost. Pain scale values decreased significantly after 4 weeks and 24 weeks. Ulcer size reduction at 4 weeks and 24 weeks, as well as clinical status, investigator, and observer grading, was also significantly improved at both time points.68

A recently published Cochrane review emphasized low-quality evidence concerning medical therapy in Buerger’s disease and stated that high-quality trials assessing the effectiveness of pharmacological agents in people with Buerger’s disease are urgently needed.69

Although widely used, there is no proven evidence for platelet function inhibitors such as aspirin or clopidogrel in TAO. Same is true for oral anticoagulants.3–5,10

Analgesia

Effective analgesia is crucial as ischemic and neuropathic pain in Buerger’s disease is usually severe. Therefore, co-treatment by pain therapy specialists is essential. Combinations of morphine or opioids and peripheral analgetics are often required in high doses. Antidepressants might be of additional value. Epidural anesthesia, neuronal block, or local analgesia is often applied.70–72 In the selected cases, spinal cord stimulation might improve not only pain control but also perfusion by inducing sympathicolysis and via antidrome mechanisms.73,74

Revascularization procedures

Due to the distal localization of arterial occlusions and the absence of recipient vessels, interventional or surgical revascularization is impossible to perform in the majority of cases. Nevertheless, especially in the older literature, series of peripheral bypass procedures in Buerger’s disease have been published with acceptable results in highly selected patients (revascularization rate: 4.6%–17.7%) and highly specialized centers, reporting up to 48.8% and 62.5% at 5 years, and 43.0% and 56.3% at 10 years, respectively.75–78

Endovascular therapy might also be effective even in extended femorotibial occlusions, but the reported numbers are small and the role of endovascular therapy in Buerger’s disease has yet to be defined.79–82

Sympathectomy

As revascularization procedures are often impossible, surgical or chemical sympathectomy is often considered, despite a lack of valid data supporting this practice. In a more recent publication of a cohort of 216 Turkish patients, sympathectomy was preferred over open surgical reconstruction or bypass procedures (81% versus 19%). Clinical outcome following sympathectomy was rated “improved” in 52.3%, “stable” in 27.8%, and “worse” in 19.8% of the patients, while seven major and 36 minor amputations were performed.83 On the other hand, lumbar sympathectomy was reported to be inferior to intravenous iloprost applications in a randomized trial by the same group.68 Thus, currently, there is no proven indication for primary sympathectomy in Buerger’s disease despite the fact that it is still widely used in many countries.

Immunosuppressive drugs

Although widely used in former times, there is no proven evidence for the use of steroids or cyclophosphamide therapy.43,84,85

Progenitor cell therapy

In the past decade, cell-based therapies with autologous progenitor cells harvested from bone marrow or peripheral blood have been advocated in critical limb ischemia, including Buerger’s disease. The cell suspensions are usually applied by intramuscular injections alongside the vascular bed of the limbs or by intra-arterial injection.86–90

Meta-analyses confirmed practicability and safety as well as positive therapeutic effects (including pain control, ulcer healing, pain-free walking ability, amputations-free survival) of cell-derived therapies in critical limb ischemia.88,91,92 Patients with Buerger’s disease responded better than patients with atherosclerotic peripheral arterieal disease in some, but not all studies.93–95 There seems to be a significant time lag of 4–8 weeks until an improvement of microcirculation becomes evident in responders after bone marrow cell transplantation.96 This lag might be especially problematic in case of severe ischemia demanding a more urgent improvement of perfusion. Results of randomized double-blinded studies are awaited, but the hype about progenitor cell therapy already seems to be over.

Intramuscular or intra-arterial progenitor cell therapies compete against surgical concepts of stimulating angio-genesis and arterialization in patients with TAO based on tibia bone distraction or fenestration, or implantation of a Kirschner wire in the tibial intramedullary canal. These procedures were also reported to result in improved outcomes including pain scores, ulcer healing, and walking distances.97–99 Nevertheless, they might be hampered by side effects as the operation takes place in an ischemic environment. Controlled and comparative studies are missing.

Immunoadsorption

Immunoadsorption (IA) is an extracorporeal procedure clearing plasma from immunoglobulins and circulating immuno-complexes approved in many immune-mediated diseases. Based on the hypothesis that Buerger’s disease is immune-mediated with humoral factors playing a major role, IA was successfully introduced in a pilot study conducted by Baumann et al100 and later introduced in clinical routine care.101 More recently, a possible effective mechanism of IA was elucidated as IA eliminates vasoconstrictive α- and endothelin receptor agonistic autoantibodies that seem to cluster in patients with Buerger’s disease.102 The pilot study revealed a fast improvement of pain, a steep increase in tcpO2-levels and decrease in tcCO2-levels, an improvement in ulcer healing, and a high return-to-work rate of the patients.100 Overall, these positive results were reproduced in a clinical routine setting.101 IA is being performed on five consecutive days for 5–6 hours per session aiming for a clearance of ~2.5-fold of patient’s plasma volume.100–102 It might be followed by the substitution of polyvalent immunoglobulin to ameliorate infectious risks in patients with active gangrene or ulcers.100

Bosentan

Referring to a first positive case report, another Spanish group published their results of a pilot study introducing the endothelin-receptor-blocking agent, bosentan, in the treatment of digital ulcers in patients with Buerger’s disease.103,104 Dosing was derived from the approved application for prophylaxis of digital ulcers in patients with scleroderma. Despite the promising results, ~1/6 of the patients had to undergo minor digital amputations: a finding, not necessarily arguing against the effectiveness of bosentan as minor amputations might have already been inevitable at presentation or might even have been made successfully possible by the treatment, and a finding that was also observed in our IA patients.101

Wound management and infection

Local wound management in ischemic lesions in Buerger’s disease is based on modern wound care standards with surgical debridement and selected wound dressings according to the wound’s stage and condition. As ischemic wounds – if at all – tend to heal very slowly, a cross-sectional and multidisciplinary concept is crucial. Wound, soft tissue, and bone infections might cause serious clinical problems and relapses as they occur in often highly ischemic states. Bacterial species and resistance spectra vary widely with gram-positive species dominating our own series (unpublished data). Starting calculated antibiotic therapy, one has to take anaerobic species and multiple resistances into account.

Outcome and social consequences

According to an older literature survey conducted by Börner and Heidrich,105 amputations were performed in 6.9%–75% of patients with TAO within 3–10 years of follow-up. Minor amputations predominated; nevertheless, major amputation rate was reported as high as 31%. The high amputation rates in the relatively young patients significantly contribute to the financial and social burden of the disease, which additionally includes job loss, early retirements, divorces, and subsequent social isolation.105

Perspective

Many decades from Buerger’s landmark report the disease he dedicated himself to remains an important health issue not only in high prevalence regions as it affects young people and induces a high social and financial burden. Hopefully, the new paradigm of an immunopathogenesis of Buerger’s disease might improve knowledge and prognosis in the future. To achieve better clinical results, integrated care in multidisciplinary and trans-sectoral teams with emphasis on lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation, pain control, wound management, and social care by professionals, social workers, and family members is necessary.106,107

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Winiwarter F. Ueber eine eigenthümliche Form von Endarteriitis und Endophlebitis mit Gangrän des Fußes [About a strange kind of endarteriitis and endophlebitis with gangrene of the foot] Arch Klin Chir. 1879;23:202–226. quoted according to ref. 39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buerger L. Landmark publication from the American Journal of the Medical Sciences,’ Thrombo-angiitis obliterans: a study of the vascular lesions leading to presenile spontaneous gangrene’. 1908. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337(4):274–284. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31818c8bc9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dargon PT, Landry GJ. Buerger’s disease. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(6):871–880. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olin JW. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):864–869. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009213431207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piazza G, Creager MA. Thromboangiitis obliterans. Circulation. 2010;121(16):1858–1861. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.942383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puéchal X, Fiessinger JN. Thromboangiitis obliterans or Buerger’s disease: challenges for the rheumatologist. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46(2):192–199. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hida N, Ohta T. Current status of patients with Buerger disease in Japan. Ann Vasc Dis. 2013;6(3):617–623. doi: 10.3400/avd.oa.13-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lie JT. The rise and fall and resurgence of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Acta Pathol Jpn. 1989;39(3):153–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1989.tb01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasaki S, Sakuma M, Kunihara T, Yasuda K. Current trends in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) in women. Am J Surg. 1999;177(4):316–320. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arkkila PE. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adar R. Epidemiology of TAO – correction of an error. Atherosclerosis. 2010;211(1):24. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsushita M, Nishikimi N, Sakurai T, Nimura Y. Decrease in prevalence of Buerger’s disease in Japan. Surgery. 1998;124(3):498–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olin JW, Young JR, Graor RA, Ruschhaupt WF, Bartholomew JR. The changing clinical spectrum of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Circulation. 1990;82(5 suppl):IV3–IV8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fazeli B. Buerger’s disease as an indicator of socioeconomic development in different societies, a cross-sectional descriptive study in the North-East of Iran. Arch Med Sci. 2010;6(3):343–347. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2010.14253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLoughlin GA, Helsby CR, Evans CC, Chapman DM. Association of HLA-A9 and HLA-B5 with Buerger’s disease. Br Med J. 1976;2(6045):1165–1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6045.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aerbajinai W, Tsuchiya T, Kimura A, Yasukochi Y, Numano F. HLA class II DNA typing in Buerger’s disease. Int J Cardiol. 1996;54(suppl):S197–S202. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(96)88790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otawa T, Jugi T, Kawano N, Mishima Y, Toyama H. Letter: HL-A antigens in thromboangiitis obliterans. JAMA. 1974;230(8):1128. doi: 10.1001/jama.230.8.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Numano F, Sasazuki T, Koyama T, et al. HLA in Buerger’s disease. Exp Clin Immunogenet. 1986;3(4):195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimura A, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi M, et al. MICA gene polymorphism in Takayasu’s arteritis and Buerger’s disease. Int J Cardiol. 1998;66(suppl 1):S107–S113. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehra NK, Jaini R. Immunogenetics of peripheral arteriopathies. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2000;23(2–4):225–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adigüzel Y, Yilmaz E, Akar N. Effect of eNOS and ET-1 polymorphisms in thromboangiitis obliterans. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2010;16(1):103–106. doi: 10.1177/1076029609336854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Z, Nakajima T, Inoue Y, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the 3′-untranslated region of MyD88 gene is associated with Buerger disease but not with Takayasu arteritis in Japanese. J Hum Genet. 2011;56(7):545–547. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pavlic V, Vujic-Aleksic V, Zubovic N, Gojkov-Vukelic M. Periodontitis and Buerger’s disease: recent advances. Acta Inform Med. 2013;21(4):250–252. doi: 10.5455/aim.2013.21.250-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwai T. Periodontal bacteremia and various vascular diseases. J Periodontal Res. 2009;44(6):689–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2008.01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazeli B, Rafatpanah H, Ravari H, Hosseini RF, Rezaee SA. Investigation of the expression of mediators of neovascularization from mononuclear leukocytes in thromboangiitis obliterans. Vascular. 2014;22(3):174–180. doi: 10.1177/1708538113477068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gulati SM, Agarwal V, Sharma V, Saha K. C3 complement components & their breakdown product (C3d) in patients of thromboangiitis obliterans. Indian J Med Res. 1986;84:607–611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halacheva K, Gulubova MV, Manolova I, Petkov D. Expression of ICAM-1, VCAM-1, E-selectin and TNF-alpha on the endothelium of femoral and iliac arteries in thromboangiitis obliterans. Acta Histochem. 2002;104(2):177–184. doi: 10.1078/0065-1281-00621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim EJ, Cho BS, Lee TS, Kim SJ, Seo JW. Morphologic change of the internal elastic lamina in Buerger’s disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15(1):44–48. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi M, Ito M, Nakagawa A, Nishikimi N, Nimura Y. Immunohistochemical analysis of arterial wall cellular infiltration in Buerger’s disease (endarteritis obliterans) J Vasc Surg. 1999;29(3):451–458. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(99)70273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee T, Seo JW, Sumpio BE, Kim SJ. Immunobiologic analysis of arterial tissue in Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003;25(5):451–457. doi: 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dellalibera-Joviliano R, Joviliano EE, Silva JS, Evora PR. Activation of cytokines corroborate with development of inflammation and autoimmunity in thromboangiitis obliterans patients. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;170(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slavov ES, Stanilova SA, Petkov DP, Dobreva ZG. Cytokine production in thromboangiitis obliterans patients: new evidence for an immune-mediated inflammatory disorder. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(2):219–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Godoy JM, Braile DM, Godoy MF. Buerger’s disease and anticardiolipin antibodies: a worse prognosis? Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2002;8(1):85–86. doi: 10.1177/107602960200800112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eichhorn J, Sima D, Lindschau C, et al. Antiendothelial cell antibodies in thromboangiitis obliterans. Am J Med Sci. 1998;315(1):17–23. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gulati SM, Madhra K, Thusoo TK, Nair SK, Saha K. Autoantibodies in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Angiology. 1982;33(10):642–651. doi: 10.1177/000331978203301003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halacheva KS, Manolova IM, Petkov DP, Andreev AP. Study of anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies in patients with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Scand J Immunol. 1998;48(5):544–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olin JW. Are anticardiolipin antibodies really important in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease)? Vasc Med. 2002;7(4):257–258. doi: 10.1191/1358863x02vm457ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira de Godoy JM, Braile DM. Buerger’s disease and anticardiolipin antibodies. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2009;10(10):792–794. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e32832ce8d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smolen JS, Youngchaiyud U, Weidinger P, et al. Autoimmunological aspects of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1978;11(2):168–177. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(78)90041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein-Weigel PF, Bimmler M, Hempel P, et al. Pattern of G-protein coupled receptor auto-antibodies in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and their removal by immunoadsorption. Vasa. 2014;43(5):347–352. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ketha SS, Cooper LT. The role of autoimmunity in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1285:15–25. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farberow NL, Nehemkis AM. Indirect self-destructive behavior in patients with Buerger’s disease. J Pers Assess. 1979;43(1):86–96. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4301_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Diehm C, Schäfer M. Das Buerger-Syndrom (Thrombangiitis obliterans) Geschichte, Epidemiologie, Pathologie, Klinik, Diagnostik und Therapie [The Buerger’s syndrome (thrombangiitis obliterans) History, epidemiology, pathology, clinic, diagnostic, and therapy] Berlin; Heidelberg; New York: Springer Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shionoya S. Diagnostic criteria of Buerger’s disease. Int J Cardiol. 1988;66(suppl 1):S243–S245. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(98)00175-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein-Weigel PF, Richter JG. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Vasa. 2014;43(5):337–346. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaki S, Sakuma M, Kunihara T, Yasuda K. Distribution of arterial involvement in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease): results of a study conducted by the Intractable Vasculitis Syndromes Research Group in Japan. Surg Today. 2000;30(7):600–605. doi: 10.1007/s005950070099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shionoya S, Ban I, Nakata Y, Matsubara J, Hirai M, Kawai S. Involvement of the iliac artery in Buerger’s disease (pathogenesis and arterial reconstruction) J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1978;19(1):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wysokinski WE, Kwiatkowska W, Maslowski L, Witkiewicz W, Kowal-Gierczak B. Buerger’s disease in two brothers: iliac artery occlusion by thromboangiitis obliterans-case reports. Angiology. 1998;49(5):409–414. doi: 10.1177/000331979804900511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Becit N, Unlü Y, Koçak H, Ceviz M. Involvement of the coronary artery in a patient with thromboangiitis obliterans. A case report. Heart Vessels. 2002;16(5):201–203. doi: 10.1007/s003800200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Calgüneri M, Oztürk MA, Ay H, et al. Buerger’s disease with multisystem involvement. A case report and a review of the literature. Angiology. 2004;55(3):325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Drake ME., Jr Winiwarter-Buerger disease (‘thromboangiitis obliterans’) with cerebral involvement. JAMA. 1982;248(15):1870–1872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harten P, Müller-Huelsbeck S, Regensburger D, Loeffler H. Multiple organ manifestations in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). A case report. Angiology. 1996;47(4):419–425. doi: 10.1177/000331979604700415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Siddiqui MZ, Reis ED, Soundararajan K, Kerstein MD. Buerger’s disease affecting mesenteric arteries: a rare cause of intestinal ischemia – a case report. Vasc Surg. 2001;35(3):235–238. doi: 10.1177/153857440103500314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fazeli B, Modaghegh H, Ravrai H, Kazemzadeh G. Thrombophlebitis migrans as a footprint of Buerger’s disease: a prospective-descriptive study in north-east of Iran. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(1):55–57. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0652-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fagrell B, Lundberg G. A simplified evaluation of vital capillary microscopy for predicting skin viability in patients with severe arterial insufficiency. Clin Physiol. 1984;4(5):403–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1984.tb00125.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ranft J, Lammersen T, Heidrich H. In-vivo capillary-microscopical findings in patients with thromboangiitis obliterans, progressive systemic scleroderma, and rheumatoid arthritis, respectively. Klin Wochenschr. 1986;64(19):946–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lawrence PF, Lund OI, Jimenez JC, Muttalib R. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(1):210–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lie JT. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and smokeless tobacco. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(6):812–813. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cooper LT, Henderson SS, Ballman KV, et al. A prospective, case-control study of tobacco dependence in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s Disease) Angiology. 2006;57(1):73–78. doi: 10.1177/000331970605700110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hooten WM, Bruns HK, Hays JT. Inpatient treatment of severe nicotine dependence in a patient with thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73(6):529–532. doi: 10.4065/73.6.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jiménez-Ruiz CA, Dale LC, Astray Mochales J, Velázquez Buendía L, de Granda Orive I, Guirao García A. Smoking characteristics and cessation in patients with thromboangiitis obliterans. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2006;65(4):217–221. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2006.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balmford J, Leifert JA, Schulz C, Elze M, Jaehne A. Implementation and effectiveness of a hospital smoking cessation service in Germany. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(1):103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rigotti NA, Munafo MR, Stead LF. Interventions for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD001837. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001837.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khati I, Menvielle G, Chollet A, Younès N, Metadieu B, Melchior M. What distinguishes successful from unsuccessful tobacco smoking cessation? Data from a study of young adults (TEMPO) Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fiessinger JN, Schäfer M. Trial of iloprost versus aspirin treatment for critical limb ischaemia of thromboangiitis obliterans. The TAO Study. Lancet. 1990;335(8689):555–557. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90346-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.The European TAO Study Group Oral iloprost in the treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1998;15(4):300–307. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(98)80032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bozkurt AK, Köksal C, Demirbas MY, et al. A randomized trial of intravenous iloprost (a stable prostacyclin analogue) versus lumbar sympathectomy in the management of Buerger’s disease. Int Angiol. 2006;25(2):162–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bozkurt AK, Cengiz K, Arslan C, et al. A stable prostacyclin analogue (iloprost) in the treatment of Buerger’s disease: a prospective analysis of 150 patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;19(2):120–125. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.11.01868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cacione DG, Baptista-Silva JC, Macedo CR. Pharmacological treatment for Buerger’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2:CD011033. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011033.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD011033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hashimoto A, Ito H, Sato Y, Fujiwara Y. Automated intermittent bolus infusion for continuous sciatic nerve block: a case report. Masui. 2011;60(7):873–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Paraskevas KI, Trigka AA, Samara M. Successful intravenous regional sympathetic blockade (Bier’s Block) with guanethidine and lidocaine in a patient with advanced Buerger’s Disease (thromboangiitis obliterans)-a case report. Angiology. 2005;56(4):493–496. doi: 10.1177/000331970505600419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Saddler JM, Crosse MM. Ischaemic pain in Buerger’s disease. Report of a female patient receiving long-term local analgesia. Anaesthesia. 1988;43(4):305–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Donas KP, Schulte S, Ktenidis K, Horsch S. The role of epidural spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of Buerger’s disease. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(5):830–836. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vaquer Quills L, Blasco González L, Asensio Samper J, Villanueva Pérez VL, López Alarcón MD, De Andrés Ibáñez J. Epidural neuro-stimulation of posterior funiculi for the treatment of Buerger’s disease. Neuromodulation. 2009;12(2):156–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Inada K, Iwashima Y, Okada A, Matsumoto K. Nonatherosclerotic segmental arterial occlusion of the extremity. Arch Surg. 1974;108(5):663–667. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1974.01350290029003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sayin A, Bozkurt AK, Tüzün H, Vural FS, Erdog G, Ozer M. Surgical treatment of Buerger’s disease: experience with 216 patients. Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;1(4):377–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shionoya S, Ban I, Nakata Y, Matsubara J, Hirai M, Kawai S. Surgical treatment of Buerger’s disease. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1980;21(1):77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sasajima T, Kubo Y, Inaba M, Goh K, Azuma N. Role of infrainguinal bypass in Buerger’s disease: an eighteen-year experience. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1997;13(2):186–192. doi: 10.1016/s1078-5884(97)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kawarada O, Ayabe S, Yotsukura H, et al. Subintimal angioplasty of lengthy femorotibial total occlusion in Buerger’s disease. J Endovasc Ther. 2013;20(4):578–581. doi: 10.1583/12-4139.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Graziani L, Morelli L, Parini F, et al. Clinical outcome after extended endovascular recanalization in Buerger’s disease in 20 consecutive cases. Ann Vasc Surg. 2012;26(3):387–395. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sandner TA, Degenhart C, Becker-Lienau J, Reiser MF, Treitl M. Therapie peripherer Gefäßstenosen und –verschlüsse bei Thrombangiitis obliterans [Therapy of peripheral vessel stenosis and occlusion in patients with thromboangiitis obliterans] Radiologe. 2010;50(10):887–893. doi: 10.1007/s00117-010-2003-z. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hodgson TJ, Gaines PA, Beard JD. Thrombolysis and angioplasty for acute lower limb ischemia in Buerger’s disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1994;17(6):333–335. doi: 10.1007/BF00203953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bozkurt AK, Beşirli K, Köksal C, et al. Surgical treatment of Buerger’s disease. Vascular. 2004;12(3):192–197. doi: 10.1258/rsmvasc.12.3.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saha K, Chabra N, Gulati SM. Treatment of patients with thromboangiitis obliterans with cyclophosphamide. Angiology. 2001;52(6):399–407. doi: 10.1177/000331970105200605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gur’eva MS, Baranov AA, Bagrakova SV, Kurdiukov AA. Pul’s-terapiia gliukokortikoidami i tsiklofosfamidom v lechenii obliteriruiushchego trombangiita [Pulse-therapy with glucocorticoids and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans] Klin Med (Mosk) 2003;81(10):53–57. Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Boda Z, Udvardy M, Rázsó K, et al. Stem cell therapy: a promising and prospective approach in the treatment of patients with severe Buerger’s disease. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2009;15(5):552–560. doi: 10.1177/1076029608319882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Durdu S, Akar AR, Arat M, Sancak T, Eren NT, Ozyurda U. Autologous bone-marrow mononuclear cell implantation for patients with Rutherford grade II–III thromboangiitis obliterans. J Vasc Surg. 2006;44(4):732–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lawall H, Bramlage P, Amann B. Treatment of peripheral arterial disease using stem and progenitor cell therapy. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53(2):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.08.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee KB, Kang ES, Kim AK, et al. Stem cell therapy in patients with thromboangiitis obliterans: assessment of the long-term clinical outcome and analysis of the prognostic factors. Int J Stem Cells. 2011;4(2):88–98. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2011.4.2.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Motukuru V, Suresh KR, Vivekanand V, Raj S, Girija KR. Therapeutic angiogenesis in Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis obliterans) patients with critical limb ischemia by autologous transplantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(6 suppl):53S–60S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Teraa M, Sprengers RW, van der Graaf Y, Peters CE, Moll FL, Verhaar MC. Autologous bone marrow-derived cell therapy in patients with critical limb ischemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Ann Surg. 2013;258(6):922–929. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182854cf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benoit E, O’Donnell TF, Patel AN. Safety and efficacy of autologous cell therapy in critical limb ischemia: a systematic review. Cell Transplant. 2013;22(3):545–562. doi: 10.3727/096368912X636777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kinoshita M, Fujita Y, Katayama M, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after intramuscular transplantation of granulocyte colony stimulating factor-mobilized CD34 positive cells in patients with critical limb ischemia. Atherosclerosis. 2012;224(2):440–445. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2012.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matoba S, Tatsumi T, Murohara T, et al. Long-term clinical outcome after intramuscular implantation of bone marrow mononuclear cells (Therapeutic Angiogenesis by Cell Transplantation [TACT] trial) in patients with chronic limb ischemia. Am Heart J. 2008;156(5):1010–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Moriya J, Minamino T, Tateno K, et al. Long-term outcome of therapeutic neovascularization using peripheral blood mononuclear cells for limb ischemia. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(3):245–254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.799361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Amann B, Luedemann C, Ratei R, Schmidt-Lucke JA. Autologous bone marrow cell transplantation increases leg perfusion and reduces amputations in patients with advanced critical limb ischemia due to peripheral artery disease. Cell Transplant. 2009;18(3):371–380. doi: 10.3727/096368909788534942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Inan M, Alat I, Kutlu R, Harma A, Germen B. Successful treatment of Buerger’s Disease with intramedullary K-wire: the results of the first 11 extremities. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;29(3):277–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim DI, Kim MJ, Joh JH, et al. Angiogenesis facilitated by autologous whole bone marrow stem cell transplantation for Buerger’s disease. Stem Cells. 2006;24(5):1194–1200. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Patwa JJ, Krishnan A. Buerger’s disease (thromboangiitis obliterans)-management by ilizarov’s technique of horizontal distraction. A retrospective study of 60 cases. Indian J Surg. 2011;73(1):40–47. doi: 10.1007/s12262-010-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Baumann G, Stangl V, Klein-Weigel P, Stangl K, Laule M, Enke-Melzer K. Successful treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) with immunoadsorption: results of a pilot study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2011;100(8):683–690. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0298-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Klein-Weigel P, Köning C, Härtwig A, et al. Immunadsorption bei Thrombangiitis obliterans – eine vielversprechende therapeutische Option. Behandlungsergebnisse einer konsekutiven Patientenkohorte in der klinischen Routineversorgung [Immunoadsorption in thromboangiitis obliterans: a promising therapeutic option: results of a consecutive patient cohort treated in clinical routine care] Zentralbl Chir. 2012;137(5):460–465. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315141. German. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Klein-Weigel PF, Bimmler M, Hempel P, et al. Pattern of G-protein coupled receptor auto-antibodies in thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) and their removal by immunoadsorption. Vasa. 2014;43(5):347–352. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Todoli Parra JA, Hernández MM, Arrébola López MA. Efficacy of bosentan in digital ischemic ulcers. Ann Vasc Surg. 2010;24(5):690.e1–690.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.De Haro J, Acin F, Bleda S, Varela C, Esparza L. Treatment of thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease) with bosentan. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2012;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Börner C, Heidrich H. Long-term follow-up of thromboangiitis obliterans. Vasa. 1998;27(2):80–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Myer SA. Case studies: what a difference a nurse makes. AACN Clin Issues. 1995;6(4):576–587. doi: 10.1097/00044067-199511000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Frost-Rude JA, Nunnelee JD, Spaner S. Buerger’s disease. J Vasc Nurs. 2000;18(4):128–130. doi: 10.1067/mvn.2000.110142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]