Abstract

Compared to affluent marriages, lower income marriages develop within a context filled with negative stressors that may prove quite toxic for marital stability. The current paper argues that stressful contexts may undermine marital well-being through two routes. First, external stressors create additional problems within the marriage by diverting time and attention away from activities that promote intimacy between partners. Second, external stress may render spouses ill-equipped to cope with this increase in problems by draining spouses of the energy and resources necessary for responding to marital challenges in a constructive manner. In acknowledging the role of the marital context for relationship dynamics, this model suggests new directions for interventions designed to strengthen the marriages of lower income couples.

For most people, maintaining a satisfying marriage is one of the most important goals in life [1]. Yet many couples struggle in their attempts to achieve this goal. Despite promising beginnings, all too often the developmental course of a marriage is characterized by a rather drastic shift in relationship evaluations, such that initial feelings of love and optimism deteriorate and transform into feelings of distress and disenchantment [2]. Even more troubling, however, is that the risk of marital decline is disproportionally high among the economically disadvantaged. Since reaching its apex in the 1980s, divorce rates have steadily fallen among educated, middle class couples, yet have continued to rise among less educated, lower class couples [2, 3]. Furthermore, among marriages that remain intact, lower income spouses report significantly higher levels of marital unhappiness than do middle or higher income spouses [4].

These socioeconomic disparities in rates of marital distress and dissolution draw attention to the unique factors that shape and constrain the development of lower income marriages as compared to more affluent marriages. Perhaps the most notable differences lie in the broader environmental context within which these marriages unfold. Lower income marriages are formed and maintained in an environment characterized by myriad negative stressors, such as unemployment, non-standard work hours, unsafe neighborhoods, inadequate transportation, accumulating debts, and a relative absence of supportive social networks [5, 6, 7]. Yet, although lower income couples cite these stressors as particularly salient sources of difficulty for their marriage [8], these elements of couples’ broader social and physical environments are frequently overlooked in psychological research examining marital change and stability. Traditionally, research on relationship maintenance has focused primarily on identifying the characteristics of individuals (e.g., personality traits) and their interactions (e.g., communication skills) that predict more successful marital outcomes; as a result, the stressful elements of the marital context are often the proverbial ‘elephant in the room’, ignored rather than acknowledged as a pivotal factor that may prove quite toxic for marital well-being.

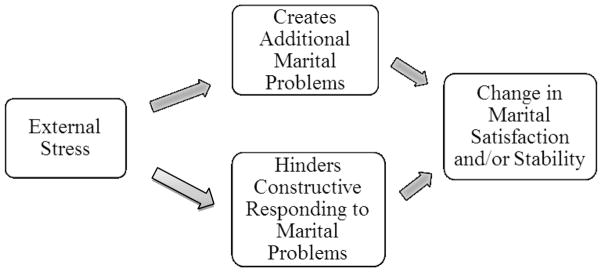

In contrast, the current paper takes the perspective that understanding marital outcomes requires understanding how stressors originating in domains external to the marriage may alter the relationship dynamics transpiring within the marriage [9, 10]. Specifically, we provide a brief overview of a model suggesting that stressful life events may undermine marital happiness and stability through two independent routes (see Figure 1). First, external stress creates additional problems and difficulties that must be addressed within the marriage. Second, external stress hinders spouses’ capacity to respond to any problems that do arise within the marriage in a constructive and adaptive manner. Each of these routes, and the evidence supporting them, are described in greater detail below.

Figure 1.

Two Route Model of Stress Effects on Marriage

Route 1: Stressful Contexts Create Additional Problems within the Marriage

The first route through which stressors outside the marriage undermine marital well-being is by reducing opportunities for activities that promote and nourish the relationship, while simultaneously increasing opportunities for conflicts and tensions to arise. For instance, naturalistic observations of family dynamics indicate that end-of-day reunion periods – the time when partners return home from work - provide key opportunities for partners to show interest in one another and to affirm relational bonds [11, 12]. When couples reside in a less stressful, less demanding context, these end-of-day reunions may be filled with such positive, shared experiences as engaging in intimate conversations or planning novel and fun leisure activities together. Yet, when couples are facing important stressors, this critical time together is often quite limited and characterized by greater disconnection and social withdrawal [13]. On days when individuals must cope with more demands outside the home, they report being more distracted and less responsive when interacting with their partner [14], they are less likely to spend time participating in couple leisure activities [15], and women in particular are less likely to engage in expressions of affection and sexual intimacy [16]. Instead, when couples do manage to carve out time to interact, that time is often allocated toward efforts to resolve their stressors [17]. For example, a couple facing the challenges associated with serious financial strains may spend their limited time together taking on the difficult task of negotiating the household budget, rather than fostering intimacy through more pleasurable pursuits, such as going out for dinner and a movie. In this way, the experience of stress can hamper the accumulation of shared, positive experiences within the relationship, which have been shown to be an essential resource for promoting positive relationship development [18, 19]. These effects may be especially pronounced for lower income couples working multiple jobs or non-standard work hours, as difficulties coordinating schedules are likely to make those key moments for intimacy even more elusive [20].

Given these concrete effects of stressful contexts on daily life, it is not surprising that couples experiencing greater stress outside the home also report experiencing more serious relational problems within the home. During periods of relatively high external stress, couples are more likely to indicate they are struggling with such relational issues as having less time to connect with one another, a lack of intimacy within the marriage, feeling neglected by their partner, and increased differences in attitudes with the partner [21, 22]. In essence, stressful contexts impose additional challenges on the couple, by constraining the types of experiences couples accrue within the relationship, which ultimately can erode marital happiness.

Route 2: Stressful Contexts Hinder Constructive Responses to Marital Problems

A consequence of less time spent engaged in positive, shared experiences and more time spent confronting difficult challenges is that effective relationship maintenance efforts and problem-solving tactics become particularly important for couples under stress. In other words, to the extent that couples residing in stressful contexts are able to communicate effectively and successfully manage their problems together, they should be less likely to exhibit declines in their marital quality over time [23]. Yet, growing research indicates that the experience of stress may render spouses ill-equipped to face an increase in relational challenges. The second route through which stressors outside the marriage undermine marital well-being is by depleting spouses of the energy and resources necessary for navigating any challenges that do arise within the marriage in a constructive manner.

The rationale for this argument stems from research indicating that many constructive, relationship-oriented behaviors, such as biting one’s tongue when your partner makes a critical remark, forgiving a partner’s insensitive behavior, or adopting the partner’s perspective when discussing conflicts, require greater effort and self-control to enact compared to more selfish and destructive behaviors [24]. Unfortunately, according to theories of self-regulation, self-control may be a limited resource. A wealth of evidence suggests that exerting self-control in one domain can create a state of self-regulatory depletion, which then interferes with self-control efforts in other domains [25, 26]. Consequently, spouses may find it more difficult to engage in these types of constructive relationship behaviors at times when their energy and resources are being diverted toward coping with stressors outside the marriage.

Supporting this notion, several recent findings indicate that external stress is associated with the way spouses interpret and respond to challenges within the relationship. For example, stress seems to impede effective problem-solving, as couples experiencing greater financial strain are less constructive when discussing their marital problems than are couples who are more financially secure [27]. Specifically, studies of observed marital interactions have linked economic hardship to increases in couples’ hostile and contemptuous behaviors [23], decreases in marital warmth [28], and the more frequent use of demand/withdraw communication patterns, a maladaptive pattern in which one spouse denigrates or makes demands of the partner, while the partner responds by refusing to discuss the issue or becoming defensive [29]. Additional studies suggest that stress also may impair effective support provision within the marriage. Husbands facing greater stress outside the marriage are less likely to provide support that matches the needs of their partner, perhaps because stress hampers the ability to accurately assess their partner’s support desires [30]. One recent study underscores just how corrosive a stressful context may be for couples’ communication. A study of the in-home problem-solving and support conversations of 414 ethnically diverse newlywed couples found that financial strain and stressful life events were a stronger predictor of negative communication behaviors than were childhood and family-of-origin experiences, depressive symptoms, and even relationship satisfaction [31].

Several longitudinal studies examining fluctuations in spouses’ stress over time provide more direct evidence for the detrimental effects of increased stress on relationship functioning. For instance, during periods of heightened stress, spouses’ capacity to forgive their partner’s inconsiderate behaviors is diminished. A study of newlywed couples found that at times when spouses were experiencing greater stress, they were more likely to make blaming attributions for their partner’s negative behaviors. Conversely, during times of lower stress, these same individuals gave their partners the benefit of the doubt and excused their bad behaviors [21]. Similarly, stress seems to exacerbate spouses’ reactivity to daily conflicts within the relationship; that is, during times of greater stress, negative relationship experiences are viewed as more diagnostic of the state of the relationship and thus are more strongly associated with overall marital satisfaction. During times of lower stress, however, this link between minor daily conflicts and general marital happiness is reduced [32].

A recent daily diary study has gone a step further, confirming self-regulatory depletion as the mechanism through which stress may undermine positive relationship functioning. Newlywed couples reported their experiences with external stress, their feelings of depletion, and their relationship behaviors each night over a two-week period. Spouses reported greater feelings of depletion on days in which they experienced more stress outside the home, and these feelings of daily depletion accounted for increases in their argumentative behaviors in the home on high stress days [33]. Together, these studies examining how fluctuating stress levels correspond with changes in relationship behaviors highlight a crucial point: even spouses who generally exhibit good relationship functioning can find it difficult to engage in constructive relationship behaviors as their stress level rises. In other words, it seems that the very times spouses need their relationship skills the most are precisely the times it may be most difficult to draw upon and use those skills.

Conclusions and Implications for Intervention

In sum, stressful contexts fundamentally alter relationship dynamics in a manner that can make it quite difficult to sustain a happy and fulfilling marriage. Couples coping with economic hardship are in the untenable position of having to overcome greater challenges within the marriage, while having fewer resources available for successfully surmounting these difficulties. Importantly, the research acknowledging this reality points to new avenues for marital interventions. To date, public policy and interventions designed to alleviate relationship distress in low income populations has focused largely on teaching couples more constructive ways of communicating [34, 35, 36]. The assumption is that once couples are given the tools needed for engaging in positive relationship skills, the relationship will improve, regardless of the context in which couples reside. Yet, as indicated by the work reviewed here, this assumption may be misguided. In fact, skills-based interventions have proven to be remarkably unsuccessful in strengthening the relationships of lower income couples [35, 36]. Instead, initial evidence from several small-scale interventions indicates that increasing couples’ financial stability can serve to increase their relationship stability as well. For instance, lower income adults randomly assigned to receive interventions such as job skills training, child care assistance, or health care subsidies are more likely to be in a stable relationship three to five years later compared to adults who don’t receive these benefits [36]. It seems that reducing the stressors of the marital context provides couples with a more supportive environment for effectively using the relationship skills they may already possess. Based on these promising results, we argue that the role stressful contexts play in shaping relational processes deserves greater emphasis in research and interventions aimed at understanding and preventing marital distress.

Highlights.

Risk for marital distress is significantly greater for lower income couples.

Lower income marriages develop in a context filled with negative stressors.

Stressful events outside the marriage create more problems within the marriage.

Stressful events also hinder spouses’ capacity to address problems constructively.

Interventions targeting the stress of economic hardship may aid marital outcomes.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Lisa A. Neff, The University of Texas at Austin

Benjamin R. Karney, UCLA

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

- 1.Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Contextual influences on marriage: Implications for policy and intervention. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14:171–174. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherlin AJ. Demographic trends in the United States: A review of research in the 2000s. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72:403–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin SP. Trends in marital dissolution by women’s education in the United States. Demogr Res. 2006;15:537–560. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amato PR, Johnson DR, Booth A, Rogers SJ. Continuity and change in marital quality between 1980 and 2000. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ooms T, Wilson P. The challenges of offering relationship and marriage education to low-income populations. Fam Relat. 2004;53:440–447. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trail TE, Karney BR. What’s (not) wrong with low-income marriages. J Marriage Fam. 2012;74:413–427. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackson GL, Kennedy D, Bradbury TN, Karney BR. A social network comparison of low-income Black and White newlywed couples. J Marriage Fam. 2014;76:967–982. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *8.Jackson GL, Trail TE, Kennedy DP, Williamson HC, Bradbury TN, Karney BR. The salience and severity of relationship problems among low-income couples. J Fam Psychol. 2016;30:2–11. doi: 10.1037/fam0000158. This paper demonstrates that when lower income couples are asked to generate a list of the problems that pose the most difficulty for their marriage, stressors external to the marriage (e.g., financial strain) emerge as more salient than do relational issues such as communication. These findings highlight the importance of understanding the role of external stress for marital outcomes. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karney BR, Neff LA. Couples and stress: How demands outside a relationship affect intimacy within the relationship. In: Simpson JA, Campbell L, editors. The Oxford handbook of close relationships. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 664–684. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neff LA. Putting marriage in its context: The influence of external stress on early marital development. In: Campbell L, Loving TJ, editors. Interdisciplinary research on close relationships: The case for integration. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 179–203. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos B, Graesch AP, Repetti R, Bradbury T, Ochs E. Opportunity for interaction? A naturalistic observation study of dual-earner families after work and school. J Fam Psychol. 2009;23:798–807. doi: 10.1037/a0015824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milek A, Butler EA, Bodenmann G. The interplay of couple’s shared time, women’s intimacy, and intradyadic stress. J Fam Psychol. 2015;29:831–842. doi: 10.1037/fam0000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Repetti R, Wang S, Saxbe D. Bringing it all back home: How outside stressors shape families’ everyday lives. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:106–111. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Story LB, Repetti R. Daily occupational stressors and marital behavior. J Fam Psychol. 2006;20:690–700. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crouter AC, Perry-Jenkins M, Huston TL, Crawford DW. The influence of work-induced psychological states on behavior at home. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 1989;10:273–292. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bodenmann G, Ledermann T, Bradbury TN. Stress, sex, and satisfaction in marriage. Pers Relatsh. 2007;14:551–569. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randall AK, Bodenmann G. The role of stress on close relationships and marital satisfaction. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feeney BC, Lemay EJ. Surviving relationship threats: The role of emotional capital. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2012;38:1004–1017. doi: 10.1177/0146167212442971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Girme YU, Overall NC, Faingataa S. ‘Date nights’ take two: The maintenance function of shared relationship activities. Pers Relatsh. 2014;21:125–149. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craig L, Brown JE. Weekend work and leisure time with family and friends: Who misses out? J Marriage Fam. 2014;76:710–727. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neff LA, Karney BR. How does context affect intimate relationships? Linking external stress and cognitive processes within marriage. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2004;30:134–148. doi: 10.1177/0146167203255984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *22.Falconier MK, Nussbeck F, Bodenmann G, Schneider H, Bradbury TN. Stress from daily hassles in couples: Its effects on intradyadic stress, relationship satisfaction, and physical and psychological well-being. J Marital Fam Ther. 2015;41:221–235. doi: 10.1111/jmft.12073. A path model revealed that increases in relational problems (i.e., intradyadic stress) mediated the link between stress from daily hassles and relationship satisfaction; that is, spouses reporting greater stress from daily hassles also reported experiencing more problems within the relationship, and this increase in relational problems accounted for the lower levels of relationship satisfaction reported by highly stressed spouses. Thus, this study provides evidence for the first route of the model: stress outside the relationship can give rise to additional problems within the relationship. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Masarik AS, Martin MJ, Ferrer E, Lorenz FO, Conger KJ, Conger RD. Couple resilience to economic pressure over time and across generations. J Marriage Fam. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jomf.12284. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burnette JL, Davisson EK, Finkel EJ, Van Tongeren DR, Hui CM, Hoyle RH. Self- control and forgiveness: A meta-analytic review. Soc Psychol Personal Sci. 2014;5:443–450. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumeister RF. Self-regulation, ego depletion, and inhibition. Neuropsychologia. 2014;653:13–319. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hagger MS, Wood C, Stiff C, Chatzisarantis ND. Ego depletion and the strength model of self-control: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:495–525. doi: 10.1037/a0019486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conger RD, Conger KJ. Understanding the processes through which economic hardship influences families and children. In: Crane DR, Heaton TB, editors. Handbook of families and poverty. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008. pp. 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Abraham WT, Gardner KA, Melby JM, Bryant C, Conger RD. Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Pers Relatsh. 2003;10:389–409. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Barton AW, Futris TG, Nielsen RB. Linking financial distress to marital quality: The intermediary roles of demand/withdraw and spousal gratitude expressions. Pers Relatsh. 2015;22:536–549. This study revealed that increases in negative communication patterns mediated the link between financial strain and marital satisfaction. Specifically, spouses experiencing greater financial stress were more likely to engage in demand/withdraw communication patterns, which in turn predicted lowered marital satisfaction. Thus, this study provides evidence for the second route of the model: stress outside the relationship can interfere with effective responses to marital challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brock RL, Lawrence E. Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and contextual risk factors for overprovision of partner support in marriage. J Fam Psychol. 2014;28:54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0035280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson HC, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Financial strain and stressful events predict newlyweds’ negative communication independent of relationship satisfaction. J Fam Psychol. 2013;27:65–75. doi: 10.1037/a0031104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neff LA, Karney BR. Stress and reactivity to daily relationship experiences: How stress hinders adaptive processes in marriage. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009;97:435–450. doi: 10.1037/a0015663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buck AA, Neff LA. Stress spillover in early marriage: The role of self-regulatory depletion. J Fam Psychol. 2012;26:698–708. doi: 10.1037/a0029260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnson MD, Bradbury TN. Contributions of social learning theory to the promotion of healthy relationships: Asset or liability? J Fam Theory Rev. 2015;7:13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson MD. Healthy marriage initiatives: On the need for empiricism in policy implementation. Am Psychol. 2012;67:296–308. doi: 10.1037/a0027743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Lavner JA, Karney BR, Bradbury TN. Strengthening low-income couples and families. Behavioral Science & Policy. 2015;1:1–12. This paper is a policy analysis which reviews three federally-funded, large-scale initiatives designed to improve the relationships of lower income couples through relationship education programs. The paper notes that these initiatives were largely unsuccessful, due to their lack of consideration for the unique stressors that lower income couples face. The authors then review several smaller scale programs directly targeting couples’ economic hardship that have had more success in strengthening couples’ relationships. [Google Scholar]