Abstract

Upon conviction, individuals receive the stigmatizing label “criminal offender.” Existing stereotypes about criminal offenders may be integrated into the self-concept, a phenomenon known as self-stigma. In many stigmatized groups, self-stigma is a robust predictor of poor functioning (Livingston & Boyd, 2010; Schomerus et al., 2011). However, little is known about how self-stigma occurs (Corrigan et al., 2006), and there has been limited research with criminal offenders. This study examines a theoretical model of self-stigma in which perceived stigma leads to stereotype agreement, internalized stigma, and then to anticipated stigma. A sample of 203 male jail inmates completed assessments of these constructs just prior to release. Results show a significant indirect path from perceived stigma to stereotype agreement to internalized stigma, but not to anticipated stigma. However, perceived stigma was directly related to anticipated stigma. In conclusion, perceived stigma affects the self through two processes: it indirectly leads to internalized stigma through one avenue, and directly leads to anticipated stigma through a separate avenue. Race, criminal identity, and attitudes toward criminals were examined as moderators.

Keywords: internalized stigma, anticipated stigma, criminal offenders

The Self-Stigma Process in Criminal Offenders

Upon conviction, people receive the stigmatizing label “criminal offender.” Criminal offenders are a highly stigmatized group of people (LeBel, 2012). Sanctions placed on offenders marginalize them and severely restrict their participation in community activities (Legal Action Center, 2004). Job applications often require applicants to report criminal convictions. In many states, people with drug distribution convictions are permanently banned from receiving public assistance, those with violent offenses can be banned from public housing (Pogorzelski et al., 2005), and those with felonies can be permanently banned from voting (The Sentencing Project, 2012). Offenders also face restrictions on loans, driver’s licenses, college enrollment, and custody of children (Pogorzelski et al., 2005). For a list of state and federal restrictions on people with criminal records and information about the collateral consequences of a criminal record see Legal Action Center (2004) and National Research Council (2014).

In addition to structural sanctions, offenders endure a great deal of social stigma (i.e., negative attitudes and discrimination from community members). Offenders are often blamed for their status as a “criminal,” increasing the likelihood of stigmatization (Dijker & Koomen, 2007). Employers are less likely to hire people with a criminal record (Pager, 2003). In addition, a poll of 2,000 people in the public showed that half agreed with negative stereotypes about ex-offenders (Hirschfield & Piquero, 2010) and other studies show that the public supports structural sanctions against offenders (Dhami & Cruise, 2013), though college students seem to hold less negative attitudes toward offenders (Moore, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2013). Taken together with structural stigma, this presents a significant level of stigmatization that has the potential to impact the self. Yet, a cohesive model of self-stigma has not been examined in offenders.

A Theoretical Model of Self-Stigma

The term “self-stigma” is often used interchangeably with “internalized stigma,” but the two terms are distinct here. Here, “self-stigma” describes the overarching process through which stigma impacts the self (i.e., Corrigan, Watson, & Barr, 2006), and internalized stigma is one component in this process. It is important to note the conceptual confusion surrounding internalized stigma. There are a multitude of internalized stigma definitions (see Livingston & Boyd, 2010), and many measures of internalized stigma are confounded with other constructs such as enacted stigma (Dickerson et al., 2002), perceived stigma (Livingston & Boyd, 2010), or a combination of several constructs (Holzemer et al., 2009; Kanter, Rusch, & Brondino, 2008). Research supports the idea that acceptance of stereotypes as personally descriptive is the defining feature of internalized stigma (Nabors et al., 2014; Quinn & Earnshaw, 2013).

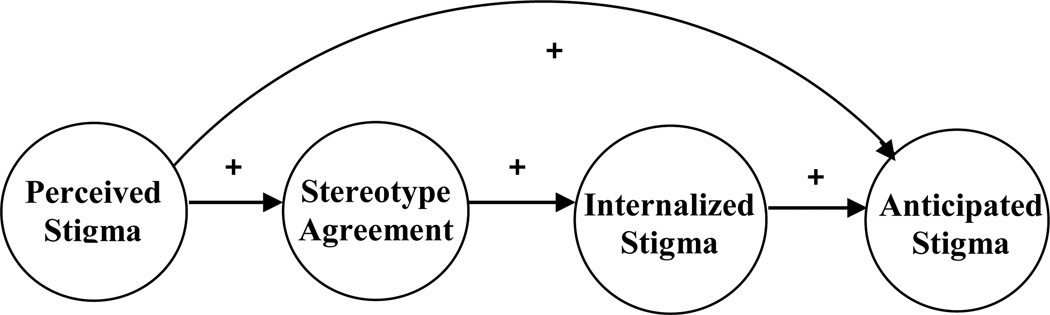

A clear conceptualization of the self-stigma process is presented by Corrigan et al., (2006). To be consistent with the literature, widely-used terminology is used here to describe components of the self-stigma process. Many researchers (Link et al., 1989; Thoits, 2011; Corrigan et al., 2006) agree that the process begins with perceived stigma, the perception that others hold negative stereotypes about one’s group (i.e., referred to as stereotype awareness by Corrigan et al., 2006, group stigma by LeBel, 2012, and discrimination/devaluation by Link, 1987). After perceiving stigma, people can agree that stereotypes truly reflect the group, referred to as stereotype agreement (Corrigan et al., 2006). This leads to internalized stigma, the acceptance of negative stereotypes as true of the self1 (i.e., referred to as stereotype concurrence by Corrigan et al., 2006). We extend this process by suggesting that internalized stigma leads to anticipated stigma, the expectation of being discriminated against (Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). Though similar, anticipated stigma is distinct from perceived stigma, as it focuses on the self rather than the group as a whole (Taylor et al., 1994; LeBel, 2012) and emphasizes future expectations. This hypothesized model is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Model of Self-Stigma Process.

Figure 1 is a progressive model; more distal parts of the process (i.e., perceived and internalized stigma) should not be as strongly related as more proximal parts (i.e., stereotype agreement and internalized stigma; Corrigan, Rafacz, & Rusch, 2011). The current study examines a comprehensive model of self-stigma in the understudied population of criminal offenders. Each link of the self-stigma process is described below, noting points at which this process may be unique for criminal offenders.

Empirical Research on the Self-Stigma Process

Perceived Stigma and Stereotype Agreement

Research on perceived stigma and stereotype agreement is mixed. These variables are unrelated in people with mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2006) and people who stutter (Boyle, 2013), but modestly correlated in other samples of people with mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2011), and people with alcohol dependence (Schomerus et al., 2011). These mixed results may reflect the nature of the stigmatized attribute. A physical disability (i.e., stuttering) is viewed as having low controllability (Corrigan, Markowitz, Watson, Rowan, & Kubiak, 2003); people in these groups may perceive a great deal of stigma, but disagree with stereotypes. Attributes like drug addiction or having a criminal record are generally viewed as controllable and hence worthy of blame, even among people with these attributes. Hence, these stigmatized people may perceive that others hold stigmatizing beliefs and personally believe that stereotypes apply to the group.

Stereotype Agreement and Internalized Stigma

When stigmatized people agree with stereotypes about their group, they must reconcile these negative beliefs with their membership in the group. Stereotype agreement and internalized stigma are consistently, positively related in people with mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2006; Corrigan et al., 2011; Watson, Corrigan, Larson, & Sells, 2007), people with alcohol dependence (Schomerus et al., 2011), and people who stutter (Boyle, 2013). Because this positive relationship is found across stigmatized groups, it is also expected to occur among criminal offenders.

Internalized Stigma and Anticipated Stigma

When people believe they possess negative stereotyped qualities (i.e., internalized stigma), they may be especially likely to anticipate stigma in those domains, if not more generally, from outgroup members (Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012). Though little research has assessed anticipated stigma, one study supports this theoretical link. Earnshaw, Quinn, and Park (2012) found that anticipated stigma from healthcare providers explained the link between internalized stigma and quality of life among people with chronic illnesses.

Perceived and Anticipated Stigma

Perceived stigma likely leads to anticipated stigma outside of the process through which stereotypes are internalized. Perceived stigma may not always lead to agreement with stereotypes, and therefore may not threaten the self and cause internalized stigma (i.e., “People think criminals are dangerous, but I don’t think that about criminals or myself”). However, people who perceive stigma can still recognize discriminatory treatment as a possibility and anticipate stigma (i.e., “People think criminals are dangerous and even though I don’t, I expect discrimination.”). The two studies examining perceived and anticipated stigma (Moore et al., 2013; Moore, Stuewig, & Tangney, in press) show a direct relationship between these variables among criminal offenders.

Stigma Research with Offenders

Though research shows that prison and jail inmates do perceive and anticipate a great deal of stigma from their community (Winnick & Bodkin, 2008; LeBel, 2012; Moore et al., 2013), there have been no studies of stereotype agreement or internalized stigma, as defined here, with offenders. Two studies purporting to examine internalized stigma in offenders (Schneider & McKim, 2003; Chui and Cheng, 2013) were qualitative and examined the associated emotional, cognitive, and behavioral consequences of internalized stigma, but did not assess acceptance of stereotypes specifically.

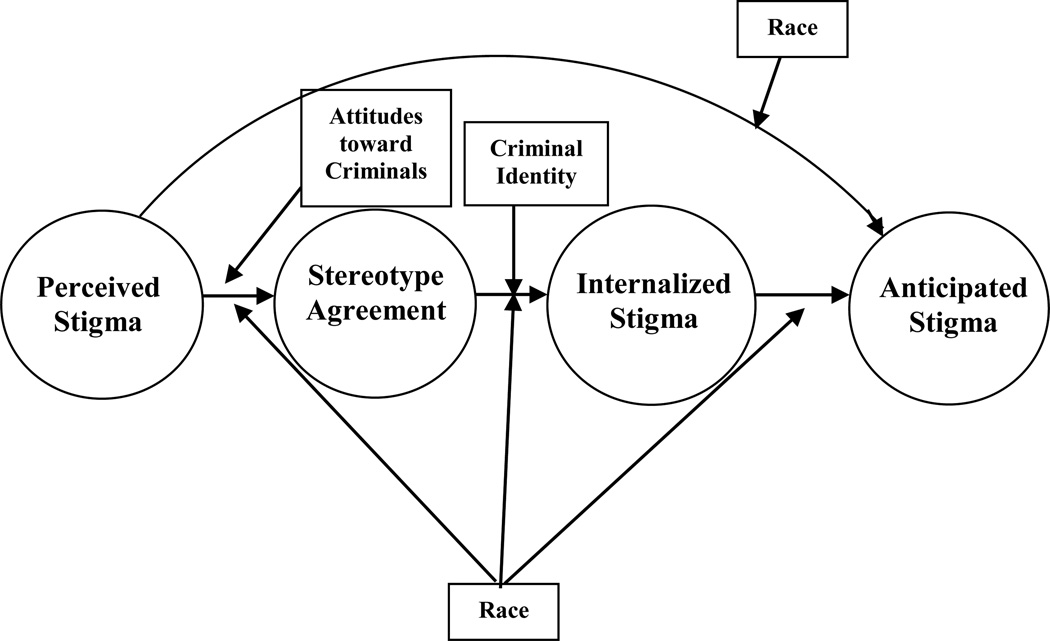

Moderators of the Self-Stigma Process

Little research has examined moderators of the links in the self-stigma process. Because there is variation in how people experience stigma (Watson & River, 2007), certain characteristics likely moderate the process through which self-stigma occurs. The hypothesized model including moderators is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized Moderators of Self-stigma Process.

Strong identification with the stigmatized group (i.e., group identification) is thought to protect the self-concept in response to perceived stigma (Jetten, Branscombe, Schmitt, & Spears, 2001). Researchers operationalize group identification differently across studies, but two aspects were chosen in the current study: in-group affect (the degree of positive or negative feelings toward other members of the group; Cameron, 2004; Walters, 2003), and identification, the degree to which individuals see themselves as members of the group (Jetten et al., 2001). With regard to in-group affect, people who generally have positive attitudes toward others in their stigmatized group are likely to reject the veracity of stereotypes about the group (Rusch et al., 2009). Therefore, having positive attitudes about other offenders likely weakens the relationship between perceived stigma and stereotype agreement.

With regard to identification, stereotype agreement may be strongly related to internalized stigma when people identify as a member of the stigmatized group (Baretto, 2014; Thoits, 2011). If inmates do not want the stigmatized group of “criminal” to comprise a large role in their social identity, or do not see themselves as similar to others in the stigmatized group (i.e., “I’m not like other criminals”), they may distance themselves from the group or excel in stereotyped domains, which helps avoid internalizing stereotypes (Baretto, 2014).

Moderation by Race

Multiple relationships in the self-stigma process may be moderated by race. Black offenders are a highly stigmatized subset of offenders, as the prototypical image of the dangerous “Black criminal” is highly prevalent in the media (Welch, 2007). For Black offenders, perceiving stigma toward criminals may be especially threatening to the self and activate self-protective responses even at this early stage in the process. Therefore, the link between perceived stigma and stereotype agreement may be attenuated for Black offenders. The relationship between stereotype agreement and internalized stigma may also be attenuated for Black offenders. Through experiences of discrimination, people with obvious stigmas develop coping strategies to deflect stigma away from the self (Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). This may involve attributing fault to the outgroup for being unjustified in prejudice, or blaming failures on discrimination rather than personal faults (Major, 2012). In fact, Crocker and Major (1989) found racial minorities had higher self-esteem compared to non-minorities (e.g., non-stigmatized).

Present Study

This paper uses structural equation modeling to examine a process of self-stigma that draws upon Corrigan et al.’s (2006) conceptualization, in the understudied population of criminal offenders. This study extends the literature by 1) examining these variables at the multivariate level, 2) modeling anticipated stigma as part of the process, and 3) testing theoretically driven moderators, including two aspects of group identification and race. Certain types of psychological functioning, specifically self-esteem, depression, anxiety, are expected to influence the degree to which individuals report perceiving, agreeing with, accepting stereotypes, and anticipating stigma. Depressed mood and low self-esteem are characterized by negative outlook and view of the self, and anxiety can be characterized by overly negative predictions for the future. So, endorsement of internalized and anticipated stigma may be explained by psychological functioning rather than perceived stigma; Link et al., 2001) and will be controlled for. Finally, because Black and White inmates may experience multiple aspects of the self-stigma process differently, race will be tested as an exploratory moderator of all relationships.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were 203 male inmates recruited from an adult detention center in 2008–2010 as part of a randomized controlled trial of a restorative justice intervention (Folk et al., 2015). Female inmates were not included because too few were incarcerated at any given time to allow randomization. Demographic and moderator data were collected at Time 1 (baseline) and at Time 2 (post-intervention). Stigma measures were all administered concurrently at Time 3, just prior to release into the community. Inmates received a $20 honorarium for participating in the baseline assessment, and $25 for participating in the Time 3 assessment (see Folk et al., 2015 for complete description).

Only inmates who had been sentenced were eligible to participate to reduce uncertainty about release dates. Inmates were excluded if they were likely to be transferred to Department of Corrections or sentenced to electronic monitoring, or if they had U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement detainers because of difficulty following up with deportees. Only general population inmates were eligible to participate to exclude those with serious psychopathology or medical problems. Inmates were informed that participation was voluntary and that data were confidential, protected by a Certificate of Confidentiality from DHHS.

Of the eligible inmates who consented to participate (N = 230), 213 were successfully randomized to the intervention (108 in treatment, 105 in control). Of these, three withdrew from the study, four were dropped, two unexpectedly transferred, and one refused, leaving 203 participants who completed the Time 3 assessment. Of these, 111 completed stigma measures (measures added late). Further, 79 participants completed the anticipated stigma measure (measure added late). Participants (N = 203) were male, about 33 years old (range = 18 – 65), and racially/ethnically diverse (43.8% Black, 38.4% White, 4.4% Hispanic, 9.9% Mixed race/other race, 2.5% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1.0% Middle Eastern). Attrition analyses showed that participants who completed stigma measures (N = 111) did not significantly differ from those who did not (N = 92) on key variables (i.e., age, race, criminal identity, self-esteem, anxiety/depression symptoms).

Measures

Descriptive statistics for all measures are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Univariate Statistics for Continuous Variables.

| N | Mean | SD | Skew | SE | Kurtosis | SE | Possible Range |

Actual Range |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | |||||||||

| Perceived Stigma | 111 | 2.44 | .72 | .23 | .23 | −.38 | .46 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Stereotype Agreement | 111 | 1.56 | .42 | .68 | .23 | −.43 | .56 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–2.67 |

| Internalized Stigma | 111 | 1.12 | .23 | 2.54 | .23 | 6.57 | .46 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–2.11 |

| Anticipated Stigma | 79 | 1.99 | .72 | .20 | .27 | −.11 | .54 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.0–4.0 |

| Controls | |||||||||

| Depression | 174 | 53.61 | 11.53 | 1.05 | .18 | 1.45 | .37 | 30–110T | 35–97T |

| Anxiety | 175 | 52.20 | 10.85 | .89 | .18 | .75 | .37 | 30–110T | 34–89T |

| Self-esteem | 192 | 3.27 | .58 | −1.06 | .18 | 1.08 | .35 | 1.0–4.0 | 1.20–4.0 |

| Moderators | |||||||||

| Attitudes toward criminals | 111 | 4.85 | 1.40 | −.03 | .23 | −.41 | .46 | 1.0–7.0 | 1.0–7.0 |

| Criminal Identity | 190 | 2.75 | 1.84 | .59 | .18 | −1.14 | .35 | 1.0–6.0 | 1.0–6.0 |

Perceived Stigma, Stereotype Agreement, and Internalized Stigma

The Self-Stigma of Mental Illness scale (SSMI; Corrigan et al., 2006) was adapted for use with criminal offenders and entitled the Self-Stigma of Individuals with Criminal Records scale (SSICR). The SSMI scale assesses four aspects of stigma: stereotype awareness (i.e., perceived stigma), stereotype agreement, stereotype concurrence (i.e., internalized stigma), and self-esteem decrement. Self-esteem decrement was not assessed in this study. Research on offender stereotypes (Maclin & Hererra, 2006; Winnick and Bodkin, 2008; LeBel, 2012) was used to adapt the SSMI scale (see items in Table 3). Many stereotypes about people with mental illness applied to criminal offenders (e.g., dangerous, untrustworthy, disgusting, below average in intelligence, unpredictable, to blame, unable to keep a regular job, dirty). The inability to care for oneself and likelihood of not recovering/getting better items, were changed to stereotypes for offenders: “unable to be rehabilitated” and “are bad people.” Following the format of the SSMI scale, the SSICR used distinct clauses to capture perceived stigma (“The public thinks most people with a criminal record are…”), stereotype agreement (“I think most people with a criminal record are…”), and internalized stigma (Because I have a criminal record, I am…”). The wording “criminal record” was used because everyone in this sample had been convicted of a crime, and thus this phrasing applied to all participants. Labels like “criminal” or “offender” were not used because some inmates may not identify with these. Responses range from “1” Strongly Disagree to “4” Strongly Agree.

Table 3.

Latent Variables with Parceled Items as Indicators.

| Parcel 1 | Parcel 2 | Parcel 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Stigma | 1. cannot be trusted. | 4. are dirty and unkempt. | 2. are disgusting. |

| 3. are unwilling to get or keep a regular job. |

6. are below average in intelligence. |

7. are unpredictable. | |

| “The Public Believes most people with a criminal record…” |

9. are dangerous. | 10. are bad people. | 8. cannot be rehabilitated. |

| Stereotype Agreement | 1. cannot be trusted. | 2. are disgusting. | 4. are dirty and unkempt. |

| 6. are below average in intelligence. |

3. are unwilling to get or keep a regular job. |

7. are unpredictable. | |

| “I think most people with a criminal record…” |

8. cannot be rehabilitated. |

9. are dangerous. | 10. are bad people. |

|

Internalized Stigma |

1. I cannot be trusted. | 2. I am disgusting. | 6. I am below average in intelligence. |

| 4. I am dirty and unkempt. |

3. I am unwilling to get or keep a regular job. |

7. I am unpredictable. | |

| “Because I have a criminal record…” |

10. I am a bad person. | 8. I cannot be rehabilitated. |

9. I am dangerous. |

Each scale of the Self-Stigma of Individuals with a Criminal Record (SSICR) originally had 10 items (30 items total), but upon further examination, the item about being blame-worthy reduced internal consistency on all scales and had the lowest item-scale correlation for two of three scales. The concept that criminal offenders are to blame for their behavior may not be the best indicator of a negative stereotype. Most people, even offenders themselves, likely believe that criminal offenders are at fault for their law-breaking behavior, and taking responsibility/accepting blame is valued in this population. Therefore, this item was dropped, resulting in 9 items on each scale. Reliabilities ranged from excellent to acceptable: Perceived Stigma α = .92, Stereotype Agreement α = .84, Internalized stigma α = .73. Perceived Stigma and Stereotype Agreement scales were normally distributed, and the Internalized stigma scale was skewed (see Table 1), with most responses being in the lower end of the range.

Anticipated Stigma

Anticipated stigma was assessed by adapting the Discrimination Experiences subscale of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale (ISMI; Ritsher et al., 2003), a reliable measure of various stigma experiences. Four out of five items were used; the item, “People often patronize me, or treat me like a child, just because I have a mental illness” was not applicable. Items were reworded to reflect expectations of future treatment rather than past discrimination (e.g., “People discriminate against me…” was changed to “I expect people to discriminate against me…”). The adapted scale was entitled Personal Expectations of Discrimination (PED, α = .87). Responses range from “1” Strongly Disagree to “4” Strongly Agree.

Moderators

Race

Participants self-reported race upon entry into the jail; race was coded as “0” White (N = 38) and “1” Black (N = 51). There were too few participants from other racial/ethnic groups to analyze separately.

Attitudes toward Individuals with Criminal Records

The degree of positive/negative attitudes toward the stigmatized group was assessed at Time 3 just prior to release using a single item to assess the in-group affect component of group identification. The question asked, “In general, my attitudes toward people with a criminal record are _______ ?” Response options ranged from “1” Very Negative and “7” Very Positive. This variable was normally distributed (see Table 1), with only 0.9% of participants reporting very negative attitudes and 18% reporting very positive attitudes.

Criminal Identity

The identification aspect of group identification was assessed at Time 2 (post-intervention). Participants were asked to what degree they agreed with the statement “I am a criminal” on a 6-point Likert scale from “1” “totally disagree” to “6” “totally agree.” This variable was slightly skewed (see Table 1), with 40% of participants totally disagreeing they were a criminal.

Control Variables

Self-esteem, depression, anxiety, and treatment status

Levels of self-esteem, depression, and anxiety were assessed at Time 2 (post-intervention). Self-esteem was assessed using the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965). This scale contains 10 items assessing global self-worth (“1” Strong Disagree to “4” Strongly Agree, α = .87). This variable was slightly positively skewed (see Table 1). Depression and anxiety symptoms were assessed using a shortened version of the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 2007), a widely used, validated measure of psychopathology (Morey, 2007). Responses ranged from 1 = “False, not at all true” to 4 = “Very true.” The PAI uses T-scores, which are normed on a sample of average adults; the ranges were 35T - 97T for depression (24items, α = .89) and 34T - 89T for anxiety (24 items, α = .89). Because the sample in this study was drawn from a randomized controlled trial, treatment status was also controlled for. Treatment status was coded as ‘0’ if participants were assigned to the treatment as usual condition (N = 55), and ‘1’ if participants were assigned to the restorative justice intervention (N = 56).

Results

Bivariate correlations are displayed in Table 2. Data were analyzed using structural equation modeling in Mplus. Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) was used to handle missing data. FIML uses other variables in the model that have full data available for participants to estimate missing data. This approach is encouraged over listwise deletion when data are missing at random (i.e., participants are not missing on variables for reasons relevant to the phenomenon being studied) (Schafer & Graham, 2002; Wothke, 2000; Little, Jorgensen, Lang, & Moore, 2014). Of the 203 participants in our study, there was missing data on the anticipated stigma measure (N = 79), and the other stigma measures (N = 111). Control and moderator analyses involved all participants who completed those measures.2 So, in models with just stigma variables, the sample size is 111, but in models with additional variables, the sample size varies (see Table 1 for sample sizes). In our data, the stigma measures were added into the study mid-way; because this is unrelated to the phenomena being studying, it is considered missing at random. This was supported by analyses indicating people who completed stigma measures (N = 111) did not significantly differ from those who did not (N = 92) on key variables.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations.

| Perceived Stigma |

Stereotype Agreement |

Internalized stigma |

Anticipated Stigma |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Variables | ||||

| Perceived Stigma | 1.0 | .28** | .23* | .33** |

| Stereotype Agreement | .28** | 1.0 | .48*** | .02 |

| Internalized stigma | .23* | .48*** | 1.0 | .25* |

| Anticipated Stigma | .33** | .02 | .25* | 1.0 |

| Controls | ||||

| Self-esteem | −.003 | −.16 | −.22* | −.48*** |

| Anxiety | .20* | .19 | .21* | .39*** |

| Depression | .07 | .17 | .32** | .40*** |

| Treatment Status | −.25** | .00 | −.01 | .14 |

| Moderators | ||||

| Race | .001 | −.11 | −.13 | −.05 |

| Attitudes toward Criminals | −.06 | −.25** | −.07 | .13 |

| Criminal Identity | .03 | −.07 | .05 | .03 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Measurement Model

Latent variables were created for Perceived Stigma, Stereotype Agreement, Internalized Stigma, and Anticipated Stigma (latent variable names are capitalized). The four items of the PED scale were used as indicators of Anticipated Stigma. Regarding Perceived Stigma, Stereotype Agreement, and Internalized Stigma, each scale of the SSICR consisted of 9 items; instead of using all 9 items as indicators, we parceled (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, and Widaman, 2009) to create 3 indicators for each latent variable3. Further, certain items on the internalized stigma scale of the SSICR had low variance and hence were not strong indicators on their own. Parceling involves averaging multiple items to form one indicator, which simplifies structural equation models by decreasing the number of parameters estimated (Little, et al., 2009; Little et al., 2013).

To create parcels, we examined a one-construct measurement model for each scale in Mplus using the 9 respective items as indicators (Little et al., 2009). Factor loadings were inspected, and the highest three were chosen as anchors for three parcels. Items with the next-highest loadings were selected, and of those, the highest loading item was assigned to the parcel with the lowest loading, etc. until each parcel had three items. This resulted in three balanced parcels each for Perceived Stigma, Stereotype Agreement, and Internalized Stigma that served as indicators for latent variables (see Table 3). All latent variances were set to 1 to identify the measurement model, freeing all factor loadings to be estimated. This model fit the data very well (χ2 (59) = 79.09, p = .04; RMSEA = .06, CI = .01 − .09; CFI = .97, SRMR = .06), and all indicators loaded significantly onto their respective factors above the accepted value of .40.

Correlations between latent variables were examined to determine whether Corrigan and colleagues’ (2006) “progressive” model was supported (i.e., variables close to each other are more correlated than those farther apart). The data mostly supported a progressive model; Perceived Stigma was more strongly related to Stereotype Agreement (r = .34, p < .001) than Internalized Stigma (r = .30, p = .005). Further, Stereotype Agreement was more strongly related to Internalized Stigma (r = .64, p < .001) than Anticipated Stigma (r = .07, p = .57). It is not uncommon for stereotype agreement to be uncorrelated with other variables (Schomerus et al., 2011). Further, Internalized and Anticipated Stigma were highly correlated (r = .39, p = .001). Anticipated Stigma, which was not included in Corrigan and colleagues’ (2006) model, was most highly correlated with Perceived Stigma (r = .43, p < .001), the variable farthest away in the model.

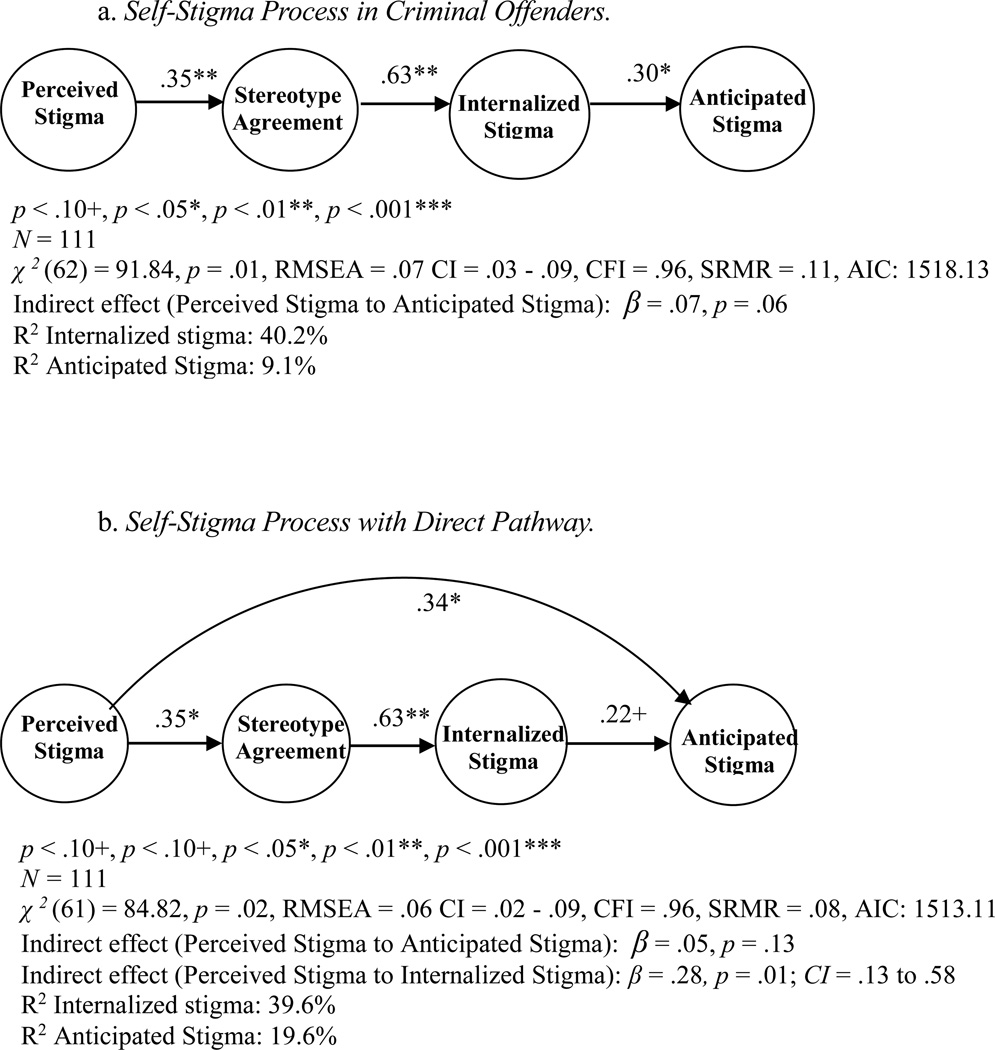

Structural Model

Structural paths were added (see Figure 3a) except the direct path from Perceived to Anticipated Stigma, which was tested separately. This model fit acceptably (χ2 (62) = 91.84, p = .01; RMSEA = .07, CI = .03 − .09; CFI = .96, SRMR = .11). Perceived Stigma was positively related to Stereotype Agreement (β = .35, p < .001), which was positively related to Internalized Stigma (β = .63, p < .001), which was positively related to Anticipated Stigma (β = .30, p = .02). The indirect path from Perceived to Anticipated Stigma was marginally significant (β = .07, p = .06), indicating an indirect effect through Stereotype Agreement and Internalized Stigma (see Figure 3a). Bias-corrected bootstrapping was conducted to obtain the most unbiased estimate of the indirect effect (Cheung & Lau, 2007). When bootstrapped, the path between Internalized and Anticipated Stigma became marginally significant (β = .25, p = .08) and the indirect effect became nonsignificant (β = .07, p = .12). Therefore, Internalized Stigma was not necessarily related to Anticipated Stigma. This model explained 12.4% of the variance in Stereotype Agreement, 40.2% of the variance in Internalized Stigma, and 9.1% of the variance in Anticipated Stigma.

Figure 3.

When the hypothesized direct path was added into the model from Perceived to Anticipated Stigma (see Figure 3b), model fit improved significantly, demonstrated by a change in model fit that surpassed the chi square value for 1 degree of freedom difference (χ2 (61) = 84.82, p = .02; RMSEA = .06, CI = .02 − .09; CFI = .96, SRMR = .08, AIC = 1513.11; χ2 (1) Δ = 7.02, p < .05). When modeling this direct effect (β = 34, p = .004), all paths remain significant with the exception of the path between Internalized and Anticipated Stigma, which became marginally significant (β= .22, p = .09). The indirect effect from Perceived to Anticipated Stigma was no longer significant (β = .05, p = .13) when the direct path was modeled. We examined whether an indirect effect remained from Perceived to Internalized Stigma (i.e., instead of Perceived to Anticipated Stigma). This does not change any parameters being modeled, but rather specifies a different indirect effect. Results showed a significant indirect effect from Perceived to Internalized Stigma (β = .22, p = .001), which remained significant after bootstrapping (β = .28, p = .01) and for which the confidence interval did not include 0 (CI = .13 to .58). This suggests full mediation from Perceived Stigma to Internalized Stigma, through Stereotype Agreement. This model explained 12% of the variance in Stereotype Agreement, 40% of the variance in Internalized Stigma, and 19.6% of the variance in Anticipated Stigma.4

Controlling for Depression, Anxiety, Self-esteem, and Treatment Status

Depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and treatment status were controlled for to remove their influence on stigma variables. First, treatment status was controlled for; treatment status had a main effect on perceived stigma, but all effects in the model remained significant. Depression, anxiety, and self-esteem were then analyzed as observed variables, predicting each stigma variable in Figure 3b. Nonsignificant effects of control variables were pruned from the model while significant main effects anxiety on Perceived Stigma, depression on Internalized Stigma, and self-esteem on Anticipated Stigma were retained (see Figure 3c). When main effects of control variables were included, all previously significant paths remained and the path from Internalized to Anticipated Stigma was nonsignificant.5

Moderators

Interactions were analyzed using the Latent Moderated Structural equations (LMS) method, which multiplies two latent variables (Klein & Moosbrugger, 2000; Maslowsky, Jager, and Hempken, 2014). Moderator analyses did not include control variables so that all available variance could be explained by interaction effects, which may also aid with attempts to replicate moderation effects. Two models are tested: Model 0 contains the baseline model (see Figure 3b) plus the main effect of the moderator on the variable of interest, and Model 1 contains everything in Model 0 plus the latent interaction. Unlike nested model comparison, Model 1 does not include fit statistics, precluding chi square difference testing. Therefore, fit statistics for Model 0 and 1 are not provided. Instead, the log-likelihood ratio test (D = −2[(log-likelihood for Model 0) – (log-likelihood for Model 1)]) is used to compare Model 0 and 1. Significance is determined using the chi square table and degrees of freedom difference between Model 0 and 1. Each moderator was analyzed in a separate model as an observed variable6. In accordance with the LMS method, all variables were standardized to aid interpretation of parameter estimates.

We hypothesized that having positive attitudes toward criminals would buffer perceived stigma, attenuating the relationship between Perceived Stigma and Stereotype Agreement. There was a main effect of attitudes toward criminals on Stereotype Agreement (β = −.22, p = .02), but the latent interaction was nonsignificant (β = −.16, p = .12). We also hypothesized that a stronger criminal identity would increase risk of internalization, strengthening the relationship between Stereotype Agreement and Internalized Stigma. Criminal identity was log-transformed to reduce positive skew. There was no main effect (β = .38, p = .33) or interaction (β = .30, p = .48).

Moderation by Race

Because racial minorities may possess more coping skills for deflecting stereotypes away from the self compared to their non-minority counterparts, race was hypothesized to attenuate certain pathways in the model, and was examined as an exploratory moderator of all other pathways. Race (Black, N = 38, White, N = 51) 7 was analyzed using the LMS method rather than a multigroup method because of sample size restrictions. Though analyzing a binary variable violates the assumption of normality, the LMS method is one of few approaches for testing the interaction of a categorical and latent continuous variable (Woods & Grimm, 2011). Muthen and Muthen (2015) approve the LMS method for this type of interaction, noting that Type 1 error can be inflated; results are interpreted cautiously.

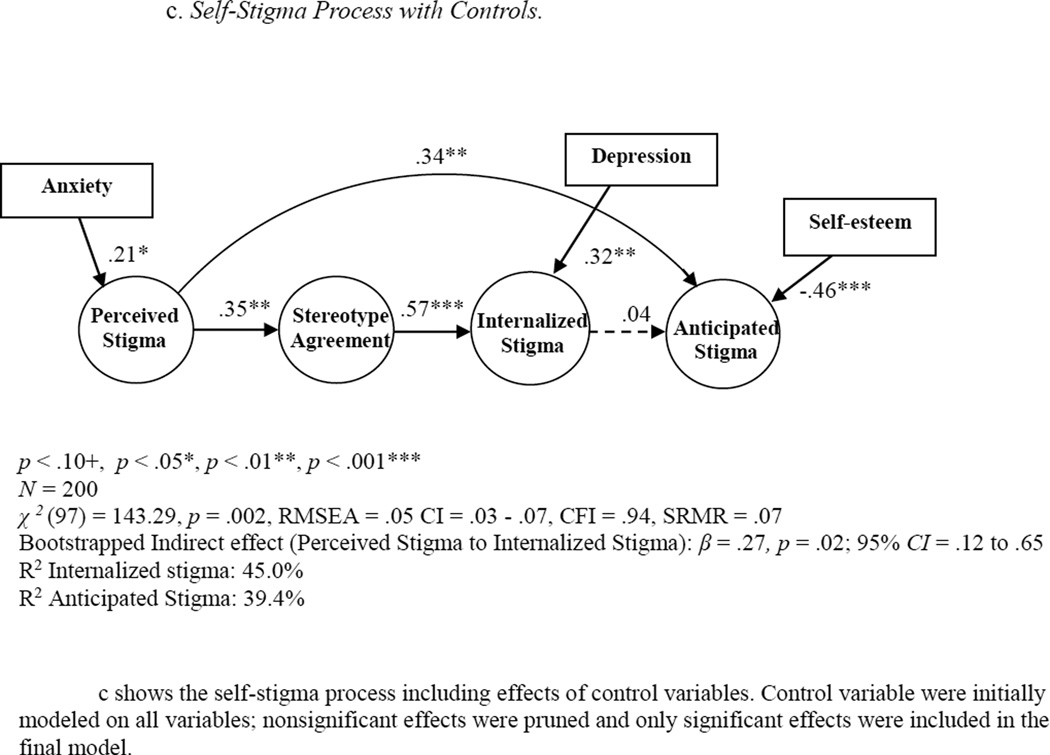

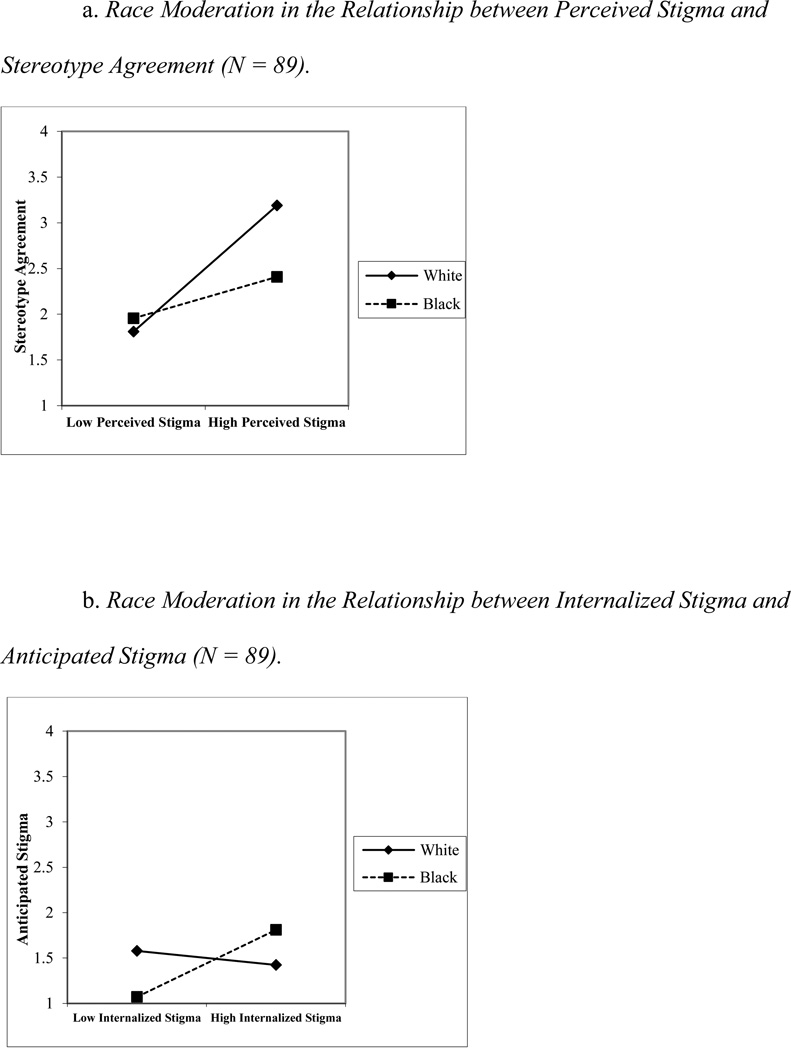

We hypothesized being a racial minority may buffer the effect of Perceived Stigma on Stereotype Agreement. There was no main effect of race on Stereotype Agreement (β = −.14, p = .18), but the latent interaction of race and Perceived Stigma was marginally significant (β = −.46, p = .06). Figure 4a shows that for White inmates, Perceived Stigma was strongly positively related to Stereotype Agreement, whereas this relationship was weaker for Black inmates.

Figure 4.

Several steps were taken to test the robustness of interaction effects. Bivariate correlations were consistent with the interaction graph, showing that perceived stigma and stereotype agreement were highly correlated for White inmates (r = .49, p = .002), and not significantly correlated for Black inmates (r = .14, p = .32); a significance test of correlations (Fischer, 1921) showed these correlations were significantly different (Z = 2.50, p = .01). Further, in comparing the two models using the log-likelihood ratio test (D = −2[(log-likelihood for Model 0) – (log-likelihood for Model 1)]), Model 1 fell just below the cutoff (3.84) for a significant degrees of freedom difference of 1 (D = −2[(−533.40) – (−531.60)], D = 3.6). This suggests that the model without the latent interaction represented a marginal loss in fit compared to the model with the latent interaction.

Similarly, we hypothesized being a racial minority may buffer the effect of Stereotype Agreement on Internalized Stigma. There was no main effect of race on Internalized Stigma (β = −.11, p = .31), and the latent interaction was nonsignificant (β = −.43, p = .13). Bivariate correlations were consistent, showing that stereotype agreement and internalized stigma were positively correlated for White (r = .53, p = .001) and Black (r = .44, p = .001) inmates, and did not differ significantly (Z = .74, p = .46).

Exploratory Race Moderation Analyses

We explored whether race moderated other model paths (i.e., Internalized to Anticipated Stigma, Perceived to Anticipated Stigma). When examining the interaction of Internalized Stigma and race predicting Anticipated Stigma, there was no main effect (β = −.03, p = .81), but the latent interaction was marginally significant (β = .22, p = .09). Figure 4b shows that for Black inmates, Internalized Stigma is positively related to Anticipated Stigma, whereas these variables are unrelated for White inmates. Similarly, internalized and anticipated stigma were positively correlated (bivariate) for Black inmates (r = .34, p = .05), but unrelated for White inmates (r = .07, p = .74); these correlations are marginally different (Z = −1.80, p = .07). The log-likelihood ratio test showed that Model 1 just fell short of the cutoff (3.84) to conclude that Model 0 was a significant loss in fit. Therefore, the model without the interaction is a marginal loss in fit compared to the model with the interaction (D = −2[(−534.26) – (−532.69)], D = 3.14).

Finally, when examining the interaction of Perceived Stigma and race in predicting Anticipated Stigma, there was no main effect. In Model 1, the latent interaction was nonsignificant (β = .11, p = .46). Bivariate correlations did show differences in the relationships between Blacks and Whites. For White inmates, perceived stigma was positively, but not significantly, related to anticipated stigma (r = .27, p = .18), whereas these variables were significantly positively correlated for Black inmates (r = .41, p = .02). These correlations were not significantly different (Z = −1.00, p = .31).

Discussion

Self-Stigma Process is Replicated in Criminal Offenders

This study provides the first quantitative examination of the self-stigma process in criminal offenders, and importantly, shows that a model of this process (based on Corrigan et al., 2006’s conceptualization) is supported. Model-testing demonstrated that believing others hold negative stereotypes led to agreement with stereotypes, which led to acceptance of those stereotypes as personally descriptive. There was a significant indirect effect from Perceived to Internalized Stigma through Stereotype Agreement. Similar to other groups (Corrigan et al., 2006; Schomerus et al., 2011; Boyle, 2013), perceived stigma and stereotype agreement are prerequisites for internalizing stigma among criminal offenders.

It is important to note that levels of internalized stigma in this sample were low, with the mean being 1.12. It is not uncommon for internalized stigma levels to be much lower than perceived stigma and stereotype agreement (Schomerus et al., 2011), however, this suggests that the overwhelming majority of inmates did not endorse internalizing stereotypes. There is some theory to suggest that offenders are not likely to internalize “deviant labels” and are more likely to justify or minimize criminal behavior, blame others, and distance themselves from other criminal offenders (Sykes & Matza, 1957). Nevertheless, because internalized stigma is a predictor of harmful outcomes in other stigmatized groups, it will be important for future research to examine the correlates and behavioral implications of internalized stigma among criminal offenders. In addition, identifying how preexisting mental health problems may increase vulnerability to internalized stigma in offenders is important to explore in future research.

One important difference in criminal offenders is the relationship between believing that others hold negative stereotypes about offenders (i.e., perceived stigma) and agreeing that those stereotypes apply to offenders as a whole (i.e., stereotype agreement). Similar to studies with people dependent on drugs (Schomerus et al., 2011), perceived stigma is closely linked to stereotype agreement in criminal offenders. These variables are unrelated in people with mental illness and people who stutter (Corrigan et al., 2006; Boyle 2013). Unlike people with mental or physical disabilities, people who commit crimes became stigmatized due to a choice they made; they are considered responsible for their stigmatized identities. Therefore, for culpable stigmatized groups, perceived stigma may incline even members of the stigmatized groups themselves to agree with negative stereotypes.

The Distinct Relationship between Perceived and Anticipated Stigma

By including anticipated stigma in this model, we examined whether self-stigma leads offenders to expect future discrimination from others. Contrary to our prediction, anticipated stigma did not directly follow from internalized stigma. When the direct effect from perceived stigma to anticipated stigma was modeled, the link between internalized stigma and anticipated stigma was attenuated, though still marginally positive. More importantly, the indirect effect of perceived stigma to anticipated stigma (i.e., through stereotype agreement and internalized stigma) was not significant. On the other hand, perceiving stigma from community members was directly related to anticipated stigma. This suggests that there are two processes through which perceived stigma impacts the self: in one avenue, offenders internalize stereotypes, and the implications of this in offenders is unknown. In a second avenue, offenders do not internalize stereotypes (e.g., stereotypes are deflected away from the self), but still expect others to discriminate against them. So, perceived stigma generates predictions of experiencing discriminatory treatment by community members, even though offenders may believe this treatment is unjustified. Moore et al., (in press) found that perceived and anticipated stigma predicted poor adjustment in the community, suggesting these variables alone have important implications for functioning.

In sum, the model analyzed in this study adds to the literature, as most studies of self-stigma do not include anticipated stigma. This model explained 19.6% of the variance in anticipated stigma, suggesting that other relevant variables may have been missing in our model. One such variable may be prior experiences with discrimination, as this would certainly influence perceived and anticipated stigma. This lays the groundwork for incorporating this important variable into other models.

Advancing the Research on Stigma in Criminal Offenders

Modeling the Self-Stigma Process

These results greatly expand the research on stigma in criminal offenders. This is the first study to examine stereotype agreement and internalized stigma in offenders, important components of the self-stigma process. In addition, the current study used quantitative, multivariate methods to examine a theoretical model of how multiple stigma variables are related in a process. Results show that self-stigma occurs in criminal offenders similar to other stigmatized groups.

Moderators of the Self-Stigma Process

Offenders who perceived stigma also agreed with stereotypes about criminal offenders, regardless of how positive or negative their attitudes were toward others offenders. Thus, the hypothesis that feeling positively about offenders would buffer this relationship was not supported. This may reflect the notion that having a criminal record is a socially unacceptable marker involving a great deal of blame, even among offenders themselves.

Contrary to our hypothesis, agreeing with stereotypes was strongly related to accepting those stereotypes as personally descriptive across inmates, regardless of how strong their social identity as a “criminal” was. This suggests that identifying as a “criminal” does not increase the chances that stereotype agreement will be harmful—it is harmful to the self regardless of whether people identify with that label. It is possible that inmates interpreted our single-item measure of criminal identity in different ways. For one inmate, strongly agreeing that he is a “criminal” may mean possessing typical qualities of an offender. For another inmate, this item may represent taking responsibility for illegal behavior, or literal interpretation of the item rather than consideration of social identity. Therefore, differences in interpretation could cancel out an interaction effect.

Participants’ race emerged as a moderator of key paths in this model. The relationship between perceived stigma and stereotype agreement was strong and positive for White inmates but nonsignificant for Black inmates. As hypothesized, for Black inmates, perceiving stigma toward offenders did not lead to agreement with stereotypes. Agreeing with negative stereotypes about the stigmatized group may be especially threatening to Black individuals’ self-concept. They must reconcile that they are Black individuals involved in the criminal justice system against the negative, stereotypical portrayal of Black “criminals.” If they agree most criminal offenders possess negative stereotypical traits, they are cognitively closer to believing they themselves fit that mold. So, even though Black inmates perceive stigma toward criminals, they may possess a self-protective mechanism that protects their racial identity and self-concept by disagreeing with stereotypes about offenders. Due to already possessing one stigmatized identity (i.e., racial minority), Black individuals are thought to possess cognitive strategies that reframe or deflect negative stereotypes away from the self-concept. White individuals, who may not have been exposed to stigma experiences, may not possess buffering cognitions that lead one to deflect stereotypes away from the self.

There were also race differences in the path between internalized and anticipated stigma. For Black inmates, internalized stigma was positively related to anticipated stigma, but these variables were unrelated for White inmates. So, for White inmates, believing that stereotypes truly described the self did not lead to expectations about being treated unfairly by the community. For White offenders, the relationship between internalized and anticipated stigma may be explained by perceived stigma, leaving no variance to be explained by internalized stigma; the stigma of having a criminal record may be so damaging that the more stigma they perceive, the more they will anticipate, regardless of whether they agree with or internalize stereotypes. Determining whether the entire internalized stigma process differs for White vs. Black offenders would require a multigroup approach. However, post-hoc analyses support this notion. The interaction of Internalized Stigma and race predicting Anticipated Stigma was examined without the direct effect of Perceived on Anticipated stigma; the interaction was nonsignificant. A graph of this null interaction showed that Internalized and Anticipated Stigma were positively related for Blacks and Whites when the direct effect was not modeled. Therefore, for White offenders, perceived stigma explains so much variance in anticipated stigma that internalized stigma no longer predicts anticipated stigma when taking perceived stigma into account.

This study did not show an interaction between Perceived Stigma and race predicting Anticipated Stigma. This is inconsistent with findings from another study of criminal offenders (Moore et al., 2013). Moore et al. (2013) found that perceived stigma interacted with race to predict anticipated stigma, such that perceived and anticipated stigma were more strongly positively correlated for Whites than Blacks. Because the current study also includes an indirect path through Stereotype Agreement and Internalized Stigma, the meaning of the direct relationship from Perceived to Anticipated Stigma changes; it reflects the offenders who did not internalize stigma, which may not vary by race. Further, though the current study did not find an interaction as was found in Moore et al. (2013), the patterns of correlations were consistent in both papers.

Including this study, there are now five studies demonstrating race differences in criminal offenders’ psychological experience with stigma (Winnick & Bodkin, 2009; LeBel, 2012; Moore et al., 2013; Moore et al., in press). Black offenders do not necessarily report lower mean levels on stigma variables compared to White offenders (Moore et al., in press), however, they appear to be less negatively impacted by stigma in various domains, supporting the idea that they possess a self-protective mechanism. Crocker and Major (1989) posed three self-protective mechanisms that Black individuals may use when confronted with stigma, including attributing poor outcomes to racial prejudice, comparing themselves only to others in their ingroup (i.e., other Black individuals), or devaluing the domains in which they are being stigmatized in. Notably, this study finds that both Black and White offenders experience a strong positive relationship between stereotype agreement and internalized stigma, and only Black offenders demonstrated a positive relationship between internalized and anticipated stigma, suggesting that a self-protective mechanism is not present at these points in the self-stigma process. Future research should continue to examine these relationships.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of this study is the lack of information available about participants’ index offense, criminal history, and prior incarceration experience. This data was not yet collected and entered at the time of these analyses. The types of crimes a person has been convicted of would certainly influence the self-stigma process, especially when considering felony vs. misdemeanor convictions. Felony convictions are associated with many more sanctions and collateral consequences (Legal Action Center, 2004). Thus, those inmates convicted of felonies or those with more extensive incarceration histories may experience higher levels of self-stigma. These are important variables to examine as correlates of the self-stigma process in future studies. The cross-sectional design limits conclusions about causality. Also, the process examined here would theoretically begin when someone first joins a stigmatized group. Because many inmates in this study had prior convictions and incarcerations, they may have had prior experiences with discrimination that influenced the self-stigma process. Prior discrimination experience may be a relevant variable to include in future research. This sample was all male, and from one specific jail. Therefore, generalizability to female inmates and inmates in different correctional facilities is yet to be determined. In particular, this research may not generalize to prisoners, who may have been convicted of more serious offenses and are incarcerated for longer periods of time in facilities farther from their communities of origin. Because there were too few participants of other races to analyze separately, we did not examine a broad range of race differences. People of other races/ethnicities may experience offender stigma differently than Blacks and Whites. It is important to note that this process would vary greatly depending on the degree to which one thinks about their stigmatized identity (i.e., stigma consciousness; Pinel, 1999) and how important this identity is in their overall social identity (i.e., identity magnitude; Earnshaw & Quinn, 2012). Specifically, if the thought of possessing a criminal record was unimportant or infrequent, there would likely be less of a relationship between stereotype agreement and internalized stigma, as well as internalized and anticipated stigma. Along these lines, people in the justice system often have multiple stigmatized identities, and another identity (i.e., HIV positive, mental illness, substance use) may comprise a larger role in one’s overall identity and hence be a better predictor of behavior. Future research should examine identity centrality and salience.

Offenders who anticipate or internalize stigma may be at risk of mental health problems including hopelessness, low self-esteem, or general distress. In addition, internalized and anticipated stigma may lead to withdrawal from the community or maladaptive behavior. For example, internalized stigma is linked to stereotype-consistent behavior (i.e., difficulty refusing alcohol for people with substance dependence). Thus, offenders who internalize stereotypes may be at risk of continued law-breaking behavior. Future research is needed to examine how offenders cope with anticipated and internalized stigma. Finally, policies against former criminal offenders severely marginalize them from conventional community members and functions. Structural barriers can contribute to maladaptive cognitive patterns, such as internalized and anticipated stigma, that make it harder to become law-abiding citizens. It is worth considering whether such policies actually serve to foster reintegration in the community.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R01 DA14694 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to June P. Tangney and Grant #5F31DA035037-02 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Kelly E. Moore. Many thanks to the members of the Human Emotions Research Lab for their assistance with this research, and the inmates who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Low self-esteem (referred to as self-esteem decrement by Corrigan et al. 2006) is sometimes conceptualized as a component of internalized stigma (Luoma et al., 2007; Corrigan et al., 2006), however, there are concerns about measuring self-esteem as a part of self-stigma (Corrigan & Calabrese, 2005). We conceptualize low self-esteem as a possible outcome resulting from internalized stigma rather than a component of the process. Therefore, self-esteem was not assessed in this study.

Although race data was available for the full sample (N = 203), we did not use FIML to estimate model parameters in race moderation analyses in order to prevent missing data from solely being estimated based on inclusion of additional demographic data.

Three indicators per latent variable is recommended in order to obtain a just-identified model, in which model misfit does not result from the measurement model, and therefore is more easily interpreted.

Due to the cross-sectional study design, alternative models were considered. Because it is plausible for anticipated stigma to cause internalized stigma (i.e., looking glass self; Maruna, LeBel, Naples, & Mitchell, 2009), a model including everything in Figure 3b, plus a path between internalized and anticipated stigma (i.e., reciprocal), was tested. This model fit well (χ2 (60) = 79.66, p = .05; RMSEA = .05, CI = .01 − .08; CFI = .97, SRMR = .06; AIC = 1509.95) and had a lower AIC than the model in Figure 3b. The path from Internalized to Anticipated Stigma was nonsignificant in this model, and the path from Anticipated to Internalized Stigma was significant. With no empirical research on the direction of the relationship between internalized and anticipated stigma, the model in Figure 3b was chosen as the superior model because it was strongly supported by theory.

To check our missing data estimation, the model including control variables was also run on the smaller sample of participants who completed only the stigma measures (N = 111); parameter estimates remained significant and in the same direction as the model run with the FIML sample.

When analyzing one item constructs with no information about reliability, the latent variable would have a residual variance of 0, and loading of 1, which constitute the same assumptions as observed variables.

Preliminary analyses show no significant differences in Black (M = 2.40, S.D. = .75) and White (M = 2.40, S.D. = .70) inmates’ perceived stigma (t(87) = −.01, p = .99), stereotype agreement (M for Blacks = 1.51, S.D. = .41, M for Whites = 1.60, S.D. = .41; t(87) = 1.02, p = .31), or internalized stigma (M for Blacks = 1.10, S.D. = .21, M for Whites = 1.16, S.D. = .28; t(87) = 1.23, p = .22).

Contributor Information

Kelly E. Moore, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

June P. Tangney, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

Jeffrey B. Stuewig, Department of Psychology, George Mason University

References

- Baretto M. Experiencing and coping with social stigma. In: Mikulincer M, Shaver PR, Dovidio JF, Simpson JA, editors. APA handbook of personality and social psychology. Vol. 2. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2014. pp. 473–506. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MP. Assessment of stigma associated with stuttering: Development and evaluation of the self-stigma of stuttering scale (4S) Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2013;56:1517–1529. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2013/12-0280). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Harvey RD. Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:135–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JE. A three-factor model of social identity. Self and Identity. 2004;3:239–262. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Lau RS. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: Bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Research Methods. 2007:296–325. [Google Scholar]

- Chui WH, Cheng KK. The mark of an ex-prisoner: perceived discrimination and self-stigma of young men after prison in Hong Kong. Deviant Behavior. 2013;34:671–684. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Calabrese JD. Strategies for assessing and diminishing self-stigma. In: Corrigan Patrick W, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 239–256. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan P, Markowitz FE, Watson A, Rowan D, Kubiak MA. An attribution model of public discrimination towards persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003:162–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Rafacz JD, Rusch N. Examining a progressive model of self-stigma and its impact on people with serious mental illness. Psychiatry Research. 2011;189:339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Barr L. The self-stigma of mental illness: Implications for self-esteem and self-efficacy. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2006;25:875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Dhami M, Cruise PA. Prisoner disenfranchisement: Prisoner and public views of an invisible punishment. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy. 2013;13:211–227. [Google Scholar]

- Dijker AJM, Koomen W. Stigmatization, tolerance, and repair: An integrative psychological analysis of responses to deviance. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma on healthcare in people living with chronic illnesses. Journal of Health Psychology. 2012;17:157–168. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM, Park CL. Anticipated stigma and quality of life among people living with chronic illnesses. Chronic Illness. 2012;8:79–88. doi: 10.1177/1742395311429393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. On the probable error of a coefficient of correlation deduced from a small sample. Metron. 1921;1:3–32. [Google Scholar]

- Folk J, Blasko B, Warden R, Schafer K, Ferssizidis P, Stuewig J, Tangney J. Feasibility and acceptability of the impact of crime group intervention with jail inmates. 2015 doi: 10.1080/15564886.2014.982777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield PJ, Piquero AR. Normalization and legitimation: Modeling stigmatizing attitudes toward ex-offenders. Criminology: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2010;48:27–55. [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, Rosa ME, Hamilton MJ, Corless I, Robinson L, Nicholas PK, Wantland DJ, Moezzi S, Williard S, Kirksey K, Portillo C, Sefcik E, Rivero-Mendez M, Maryland Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. JANAC: Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten J, Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, Spears R. Rebels with a cause: Group identification as a response to perceived discrimination from the mainstream. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:1204–1213. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter JW, Rusch LC, Brondino MJ. Depression self-stigma: A new measure and preliminary findings. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2008;196:663–670. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318183f8af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBel TP. Invisible stripes: Formerly incarcerated person’s perceptions of stigma. Deviant Behavior. 2012;33:89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Legal Action Center. After prison: Roadblocks to reentry: A report on state legal barriers facing people with criminal records. New York: Legal Action Center; 2004. http://lac.org/roadblocks-to-reentry/ [Google Scholar]

- Link BG. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: An assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening EL, Shrout PE, Dohrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach to mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–423. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatric services. 2014;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Cunningham WA, Shahar G, Widaman KF. To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:151–173. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Jorgensen TD, Lang KM, Moore EW. On the joys of missing data. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2014;39:151–162. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jst048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Rhemtulla M, Gibson K, Schoemann AM. Why the item versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods. 2013;18:285–300. doi: 10.1037/a0033266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston JD, Boyd JE. Correlates and consequences of internalized stigma for people living with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Sciences and Medicine. 2010;71:2150–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Twohig MP, Waltz T, Hayes SC, Roget N, Padilla M, Fisher G. An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1331–1346. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclin KM, Hererra V. The criminal stereotype. North American Journal of Psychology. 2006;8:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- Major B. Self, social identity, and stigma: Through Kay Deaux’s lens. In: Wiley S, Philogene G, Revenson TA, editors. Social categories in everyday experience: Decade of behavior. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Maruna S, LeBel TP, Naples M, Mitchell N. Looking-glass identity transformation: Pygmalion and golem in the rehabilitation process. In: Veysey BM, Christian J, Martinez DJ, editors. How offenders transform their lives. Cullompton, UK: Willan; 2009. pp. 30–55. [Google Scholar]

- Maslowsky J, Jager J, Hempken D. Estimating and interpreting latent interactions: A tutorial for applying the latent moderated structural equations method. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2015;39:87–96. doi: 10.1177/0165025414552301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Stuewig J, Tangney J. Jail inmates’ perceived and anticipated stigma: Implications for post-release functioning. Self and Identity. 2013;12:527–547. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2012.702425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore KE, Stuewig J, Tangney J. The effect of stigma on criminal offenders’ functioning: A longitudinal meditational model. Deviant Behavior. doi: 10.1080/01639625.2014.1004035. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory: Professional Manual. 2nd. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen L. 2015 http://statmodel.com/cgi-bin/discus/discus.cgi.

- Nabors LM, Yanos PT, Roe D, Hasson-Ohayon I, Leonhardt BL, Buck KD, Lysaker PH. Stereotype endorsement, metacognitive capacity, and self-esteem as predictors of stigma resistance in persons with schizophrenia. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2014;55:792–798. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Committee on Causes and Consequences of High Rates of Incarceration. In: Travis J, Western B, Redburn S, editors. Committee on Law and Justice, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2014. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18613/the-growth-of-incarceration-in-the-united-states-exploring-causes. [Google Scholar]

- Pager D. The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology. 2003;108:937–975. [Google Scholar]

- Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: the psychological legacy of social stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:114. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.76.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogorzelski W, Wolff N, Pan K, Blitz CL. Behavioral health problems, ex-offender reentry policies, and the “Second Chance Act.”. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1718–1724. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Chaudoir SR. Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Concealable stigmatized identities and psychological well-being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 2013;7:40–51. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritsher JB, Otilingham PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Research. 2003;121:31–49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Larson JE, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, Batia K. Self-stigma, group identification, perceived legitimacy of discrimination, and mental health service use. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195:551–552. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider A, McKim W. Stigmatization among probationers. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 2003;38:19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus G, Corrigan PW, Klauer T, Kuwert P, Freyberger HJ, Lucht M. Self-stigma in alcohol dependence: Consequences for drinking refusal self-efficacy. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:12–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykes GM, Matza D. Techniques of neutralization: A theory of delinquency. American sociological review. 1957:664–670. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor DM, Wright SC, Porter LE. Dimensions of Perceived Discrimination: The Personal/Group Discrimination Discrepancy. In: Zanna MP, Olson JM, editors. The Psychology of Prejudice: The Ontario Symposium. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1994. pp. 223–255. [Google Scholar]

- The Sentencing Project: Research and Advocacy for Reform. Annual Report. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.thesentencingproject.org/publications/AR%202012%20FINAL.pdf.

- Thoits PA. Resisting the stigma of mental illness. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2011;74:6–28. [Google Scholar]

- Walters GD. Changes in criminal thinking and identity in novice and experienced inmates: Prisonization revisited. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2003;30:399–421. [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33:1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, River PL. A social-cognitive model of personal responses to stigma. In: Corrigan PW, editor. On the stigma of mental illness: Practical strategies for research and social change. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association; 2005. pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Welch K. Black criminal stereotypes and racial profiling. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2007;23:276–288. [Google Scholar]

- Winnick TA, Bodkin M. Anticipated stigma and stigma management among those to be labeled “ex-con.”. Deviant Behavior. 2008;29:295–333. [Google Scholar]

- Winnick TA, Bodkin M. Stigma, secrecy and race: An empirical examination of black and white incarcerated men. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2009;34:131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Woods CM, Grimm KJ. Testing for nonuniform differential item functioning with multiple indicator multiple cause models. Applied Psychological Measurement. 2011;35:339–361. [Google Scholar]

- Wothke W. Longitudinal and multigroup modeling with missing data. In: Little TD, Schnabel KU, Baumert J, editors. Modeling longitudinal and multilevel data: Practical issues, applied approaches, and specific examples. 219–240. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000. pp. 269–281. [Google Scholar]