Abstract

Equivocal findings are reported for perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and self-reported pregnancy loss. We prospectively assessed PFASs and pregnancy loss in a cohort comprising 501 couples recruited preconception and followed daily through 7 post-conception weeks. Seven PFASs were quantified: 2-N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamide acetate (Et-PFOSA-AcOH); 2-N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido acetate (Me-PFOSA-AcOH); perfluorodecanoate (PFDeA); perfluorononanoate (PFNA); perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA); perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS); and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA). Women used home pregnancy test kits. Loss denoted conversion from a positive to a negative pregnancy test, onset of menses or clinical confirmation (n=98; 28%). Chemicals were log transformed and rescaled by their standard deviations to estimate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals. No significantly elevated HRs were observed for any PFASs suggesting no association with loss: Et-PFOSA-AcOH (1.04; 0.87, 1.23), Me-PFOSA-AcOH (0.79; 0.61, 1.00; p<0.05), PFDeA (0.83; 0.66, 1.04), PFNA (0.86; 0.70, 1.06), PFOSA (0.74; 0.50, 1.09), PFOS (0.81; 0.65, 1.00), and PFOA (0.93; 0.75, 1.16).

Keywords: cohort, epidemiology, miscarriage, perfluoroalkyl, perfluoroalkyl acids, polyfluoroalkyl, pregnancy loss, reproductive toxicity

Graphical abstract

1.1 Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) are chemicals with numerous commercial applications. Their chemical and thermal stability properties make PFAAs resistant to biodegradation and, thereby, become a source of environmental exposure for populations [1,2]. Common uses of PFASs include the manufacture of stain, water and soil resistant fabrics and carpeting, and also oil-resistant coatings for food packaging, fire-fighting foams, paints [3,4]. We use the term PFASs consistent with the recent call for harmonization of terminology for the weighing of human health effects [5].

Initial concern about the environmental impact of PFASs emerged in 2001 with the publication of data suggesting widespread exposure amongst wildlife and human populations [6,7]. In animals, such ubiquitous exposure stemmed from PFASs being readily absorbed without an ability for effective metabolism or elimination. Long half-lives are also reported in humans (ranging from 3.8 years for perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) to 4.8 years for perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS) and 7.3 years for perfluorohexane sulfonate (PFHS)), though species and sex differences have been reported [8,9].

Concern about possible developmental toxicity associated with PFAAs arose from recognition that they readily cross the placenta and enter the fetal circulation [10]. This observation coupled with ubiquitous exposure prompted epidemiologic investigation of PFASs and human development, which largely focused on PFOA and PFOS. In reviews focusing on PFASs and developmental toxicity in animals, exposure has been associated with diminished fetal growth and mortality among other outcomes [9,11]. Conversely, a recent systematic review focusing on human exposure concluded that PFOS and PFOA concentrations were inconsistently associated with diminished birth weight [12].

In terms of potential reproductive toxicity, a small body of literature has focused on fecundity, as measured by time-to-pregnancy (TTP), with equivocal results. Of the various PFASs assessed in cohorts of women and/or couples recruited prior to conception for whom TTP was prospectively measured, some but not all PFASs were associated with a longer TTP [13,14]. However, studies of pregnant women for whom PFAS exposures were quantified at varying times during pregnancy and assessed in relation to retrospectively reported TTP have generated equivocal findings [15-18]. While important, this latter body of evidence is restricted to women capable of achieving pregnancy and may exclude the highest exposed women if PFASs are associated with delayed conception or infertility. With regard to men, specific PFASs have been associated with changes in semen quality in a few studies, though again with equivocal results [19-22].

Another important endpoint — pregnancy loss — has been assessed for a few populations, including one highly exposed geographic residential population [23-26]. Overall results from various cross-sectional and case control analyses of various subsamples of this geographically exposed population (C8 Health Project) did not support an association between measured or pharmacokinetic-modeled serum concentrations of PFOS and PFOA and self reported pregnancy loss, as measured by retrospective recall of miscarriage and stillbirth [23-25]. The prevalence of pregnancy loss appeared to range from 12% to 17%. A follow-on study of a subset of women with pregnancies between 2008-2011 in this community who had serum samples quantified for PFOS and PFOA in 2005 -2006 also observed little evidence of an association, except when restricting the analysis to women’s first pregnancy where a 34% increased odds of pregnancy loss was observed [26]. This restriction, however, carries the assumption that the first pregnancy is representative of all pregnancies [27], which may or may not be upheld. Of note is a much higher (≈22%) prevalence of miscarriage in this follow-on study than earlier estimates for the overall group based upon retrospective reporting. Among women participating in the Danish Odense Child Cohort Study in 2010-2012, pregnant women’s serum perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) and perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA) concentrations measured before 12 weeks gestation were associated with a significantly higher adjusted odds of miscarriage when comparing women in the highest to lowest tertile (AOR 16.5 and 2.67, respectively), and despite the women’s concentrations being low relative to previously published work [28]. Moreover, neither PFOA nor PFOS concentrations were associated with miscarriage for this study cohort underscoring the importance of assessing a spectrum of PFASs.

In light of equivocal findings generated from research involving only two study populations (U.S. and Denmark), we assessed the relation between seven serum PFAS concentrations and incident pregnancy loss in a prospective cohort of women recruited prior to conception and followed through pregnancy until a loss or delivery. A unique aspect of our study is having measured human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) detected pregnancies, including those occurring early in pregnancy or the interval at greatest risk for loss and often before women enter prenatal care.

1.2 Materials and Methods

A prospective cohort design was used with preconception recruitment of couples who were discontinuing contraception for purposes of trying for pregnancy. Given the study outcome was pregnancy loss, we restricted the cohort to female partners of couples participating in the LIFE Study [29].

1.2.1 Study population and cohort

Among the 501 participating female partners, 347 (69%) had an observed hCG pregnancy. Briefly, women were recruited between 2005-2009 from 16 counties in Michigan and Texas using population based marketing and angler registries, respectively. Eligibility criteria were intentionally minimal to reflect the heterogeneity of fecundity at the population level: 1) in a committed relationship; 2) ability to communicate in English or Spanish; 3) female partner aged 18-40 years and male partner aged 18+ years; 4) menstrual cycles between 21-42 days; 5) no history of injectable hormonal contraception in past year; 6) no clinically diagnosed infertility; and 7) off contraception <2 months. All women’s urines were tested prior to enrollment to ensure they were not already pregnant. Three twin pregnancies were excluded from analysis, given their dependent data structure and high-risk status for adverse pregnancy outcomes. The final study cohort comprised 344 women with singleton pregnancies. Full human subjects approval was obtained from participating institutions, and women provided written informed consent before any data collection. Complete details are provided elsewhere [29].

1.2.2 Data collection

Upon enrollment, trained research assistants interviewed women about their lifestyles and medical/reproductive histories. Weight and height were measured using standardized anthropometric protocol [30] for quantifying body mass index (BMI; weight in kg / height in m2). Women were trained in the daily completion of journals designed for recording daily cigarette and alcohol use, menstruation, sexual intercourse and home pregnancy test results. These journals were completed daily through 7 post-conception weeks then monthly until delivery. Research assistants trained women in the proper use of the Clearblue® Fertility Monitor (Inverness Medical Innovations, Waltham, MA), which is a urinary test kit that tracks estrone-3-glucuronide and luteinizing hormone (LH) to predict the day of ovulation and used as the estimated day of conception. Women were encouraged to time intercourse on high or peak fertility days to maximize their chances of conceiving. The monitor is reported to be 99% accurate in detecting the LH surge, a marker of ovulation, relative to the gold standard of ultrasonography [31]. Also, women tested their urine each month on the day of expected menstruation using the Clearblue® digital pregnancy test, which has demonstrated sensitivity and reliability for detecting 25 mIU/mL of hCG, and demonstrated accuracy by women [32]. Pregnancy loss denoted a conversion from a positive to a negative pregnancy test, clinical confirmation, or onset of menstruation depending upon gestational dating. Upon enrollment into the cohort and before pregnancy, blood samples were obtained from all participating women and before pregnancy. Of the 344 women becoming pregnant, 332 (97%) women had sufficient serum remaining for the analysis of PFASs while concentrations were imputed for the 12 women without remaining serum.

1.2.3 Laboratory analysis

PFASs were quantified using published methods that included isotope dilution high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry with adherence to quality assurance and control [33,34]. Seven PFASs were quantified (ng/mL) in serum: perfluorodecanoate (PFDeA), PFNA, PFOA, PFOS and its precursors, perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA), 2-(N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (Et-PFOSA-AcOH) and 2-(N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido) acetate (Me-PFOSA-AcOH). The limits of detection (LODs) were 0.1 for PFNA, PFOSA, and PFOA and 0.2 for the remaining PFASs.

1.2.4 Statistical analysis

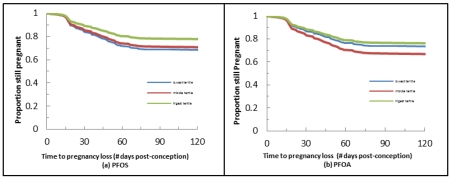

The descriptive phase of analysis sought to characterize the cohort by pregnancy and completion status to assess potential biases (e.g., attrition). Statistical significance was determined using either the Chi-square or the Kruskal-Wallis tests. Next, we assessed the distributions of PFASs to have a better understanding of the degree of exposure relative to earlier studies, and by pregnancy status. The analytic phase included the use of Cox proportional hazard modeling techniques to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for each PFAS and the time to pregnancy loss [35]. For these analyses, time denoted the number of days from observed ovulation as measured by the peak (LH) day detected by the fertility monitor and reported date of loss. We used peak LH day for estimated conception given that the ovum’s survival time for fertilization is reported to be approximately 24 hours. Approximately 17% (n=59) of menstrual cycles had missing fertility monitor data for ovulation during the conceptive cycle; the average day of ovulation as recorded by the monitor for other observed cycles was taken as the day of ovulation. For an additional 16 women (5%), fertility monitor data on ovulation was not available for any menstrual cycles requiring us to assume ovulation was 14 days prior to the first positive pregnancy test [36].

We modeled each PFAS separately to fully inspect its association with pregnancy loss, including modeling it in its continuous form after log transformation (x+1) and then rescaling by its standard deviation to aid in the interpretation of HRs, and modeling in tertiles to assess linearity. We used all machine-measured concentrations without substituting values below the LOD to avoid introducing bias when estimating human health effects [37,38]. Adjusted models included age (continuous), BMI (≤24.9 lean/normal, 25.0-29.9 overweight, ≥30.0 obese), prior pregnancy loss conditional on prior pregnancy history (no prior pregnancy, prior pregnancy but no loss and prior pregnancy and a loss), any alcohol consumption during pregnancy (no/yes), and any cigarette smoking during pregnancy (no/yes). We recognize the varying perspectives about whether or not to adjust for prior losses (39), and decided to do so but to condition on whether the woman had a prior pregnancy rather than simply modeling prior loss as a dichotomous outcome (yes/no). We imputed PFAS concentrations for 12 women without available serum for the quantification of PFASs for inclusion in the analysis of HRs (n=344) to minimize selection bias. Specifically, our imputations were done under the missing-at-random assumption and implemented Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods (40). We also repeated the analysis with each PFAS analyzed in tertiles.

1.3 Results

Overall, the study cohort comprised mostly white college educated women who were employed with health insurance and residing in households with an annual income of ≥$50,000 (Table 1). On average, women were aged 29.8 (±SD, standard deviation = 3.9) years and had a mean BMI of 27.0 (±6.7). We found little evidence to suggest systematic differences in baseline characteristics relative to completion status with one possible exception. The 24 women who withdrew from the study tended to be younger than women completing the study but only when age was categorized (p=0.03). The incidence of pregnancy loss was 28% (n=98), with all losses occurring before 21 weeks post-conception.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort by pregnancy loss status (n=344).

| Characteristics | Total n=344 |

Pregnancy Loss n=98 |

No Pregnancy Loss n=222 |

Lost To Follow-Up n = 24 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Age (years): | ||||

| ≤24 | 25 (7) | 5 (5) | 19 (9) | 1 (4) |

| 25-29 | 159 (46) | 43 (44) | 99 (45) | 17 (71) |

| 30-34 | 116 (34) | 31 (32) | 82 (37) | 3 (13) |

| ≥35 | 44 (13) | 19 (19) | 22 (10) | 3 (13)* |

| Mean (±SD) | 29.8 (3.9) | 30.3 (4.1) | 29.6 (3.8) | 29.3 (3.7) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2): | ||||

| Lean/normal (≤24.9) | 170 (49) | 44 (45) | 111 (50) | 15 (63) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 89 (26) | 23 (24) | 62 (28) | 4 (17) |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 85 (25) | 31 (32) | 49 (22) | 5 (21) |

| Mean (±SD) | 27.0 (6.7) | 27.8 (6.7) | 26.6 (6.6) | 26.9 (7.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 285 (84) | 82 (85) | 180 (82) | 23 (96) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 6 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (1) | 0 (−) |

| Hispanic | 29 (9) | 7 (7) | 21 (10) | 1 (4) |

| Other | 21 (6) | 5 (5) | 16 (7) | 0 (−) |

| Education: | ||||

| ≤High school | 15 (4) | 6 (6) | 9 (4) | 0 (−) |

| College | 325 (96) | 91 (94) | 211 (96) | 23 (100) |

| Income: | ||||

| <$50,000 | 44 (13) | 11 (12) | 30 (14) | 3 (13) |

| $50-99,999 | 163 (49) | 53 (56) | 96 (44) | 14 (58) |

| ≥$100,000 | 128 (38) | 30 (32) | 91 (42) | 7 (29) |

| Employed: | ||||

| No | 70 (20) | 22 (22) | 44 (20) | 4 (17) |

| Yes | 274 (80) | 76 (78) | 178 (80) | 20 (83) |

| Has health insurance: | ||||

| No | 15 (4) | 6 (6) | 6 (3) | 3 (13) |

| Yes | 326 (96) | 91 (94) | 214 (97) | 21 (88) |

| Research site: | ||||

| Michigan | 65 (19) | 18 (18) | 42 (19) | 5 (21) |

| Texas | 279 (81) | 80 (82) | 180 (81) | 19 (79) |

| Prior miscarriage: | ||||

| No, nulligravid | 133 (39) | 37 (38) | 86 (39) | 10 (42) |

| No, gravid | 141 (41) | 36 (37) | 93 (42) | 12 (50) |

| Yes | 68 (20) | 24 (25) | 42 (19) | 2 (8) |

| Cigarette smoking during pregnancy: |

||||

| No | 301 (89) | 83 (87) | 198 (89) | 20 (95) |

| Yes | 38 (11) | 13 (14) | 24 (11) | 1 (5) |

| Alcohol consumption during pregnancy: |

||||

| No | 157 (46) | 49 (51) | 99 (45) | 9 (43) |

| Yes | 182 (54) | 47 (49) | 123 (55) | 12 (57) |

p=0.03 for 3-way comparison

SD, standard deviation

The distributions of PFASs are shown in Table 2 and reflect that most women had concentrations above the laboratory LODs with the exception of Et-PFOSA-AcOH and PFOSA, where only 3% and 8% of concentrations were >LOD, respectively. Virtually all women had PFOS and PFOA concentrations above the LOD. Median concentrations of PFASs were similar between women becoming pregnant or not (infertile) except for slightly higher median concentrations for PFOSA (1.2 and 1.1, respectively). Of note, the concentrations of PFASs were relatively similar to those reported for participants in the NHANES biomonitoring study during a comparable time period but despite an older age distribution for NHANES [http://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/pdf/fourthreport.pdf].

Table 2. Distribution of serum PFAS concentrations (ng/mL) by pregnancy status (n=389).

| PFAA (ng/mL) | LOD | % <LOD (n=332) |

Pregnant(n=332) | % <LOD (n=57) |

Infertile (n=57) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Md | IQR | Md | IQR | ||||

| Et-PFOSA-AcOH | 0.2 | 97 | 0 | 0, 0 | 96 | 0 | 0, 0.1 |

| Me-PFOSA-AcOH | 0.2 | 26 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.5 | 26 | 0.3 | 0.1, 0.4 |

| PFDeA | 0.2 | 9 | 0.4 | 0.2, 0.6 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.2, 0.5 |

| PFNA | 0.1 | 2 | 1.2 | 0.7, 1.7 | 0 | 1.1 | 0.8, 1.4 |

| PFOSA* | 0.1 | 92 | 0 | 0, 0 | 81 | 0 | 0, 0 |

| PFOS | 0.2 | 0 | 12.2 | 8.3, 17.8 | 0 | 12.1 | 7.1, 17.1 |

| PFOA | 0.1 | 0.3 | 3.3 | 2.2, 4.9 | 0 | 3.2 | 2.5, 4.3 |

NOTE: Infertile women represent women who did not become pregnant after 12 months of trying.

p<0.05

IQR, interquartile range; LOD, limits of detection; Md, median

2-N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamide acetate (Et-PFOSA-AcOH),

2-N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamido acetate (Me-PFOSA-AcOH)

perfluorodecanoate (PFDeA)

perfluorononanoate (PFNA)

perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA)

perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)

perfluorooctanoate (PFOA)

No evidence of an increased risk of pregnancy loss was observed for any of the 7 PFAAs (Table 3). Contrarily, two PFASs were associated with a significant reduction in the risk of pregnancy loss even after adjustment. These findings included: Me-PFOSA-AcOH when modeled continuously (HR 0.79; 95% CI 0.62, 1.00; p<0.05) and PFNA (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.34, 0.94) when modeled comparing the 3rd versus 1st tertiles, respectively. Also of note is almost the complete absence of HRs above 1 for any of the PFASs with the exception of Et-PFOSA-AcOH when modeled continuously and PFOA when comparing the 2nd and 1st tertiles.

Table 3. Serum PFAS concentrations modeled continuously and in tertiles and risk of pregnancy loss (n=344).

| PFAA | Unadjusted HR (95% CI) Continuous PFAS |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)* Continuous PFAS |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) 3rd vs. 1st Tertile |

Unadjusted HR (95% CI) 2nd vs. 1st Tertile |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)* 3rd vs. 1st Tertile |

Adjusted HR (95% CI)* 2nd vs. 1st Tertile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Et-PFOSA-AcOH | 1.04 (0.89, 1.23) | 1.04 (0.87, 1.23) | 0.44 (0.09, 2.23) | NA | 0.46 (0.09, 2.47) | NA |

| Me-PFOSA-AcOH | 0.80 (0.63, 1.00) | 0.79 (0.62, 1.00)+ | 0.75 (0.45, 1.23) | 0.91 (0.55, 1.53) | 0.73 (0.44, 1.22) | 0.84 (0.50, 1.42) |

| PFDeA | 0.86 (0.69, 1.08) | 0.83 (0.66, 1.04) | 0.77 (0.47, 1.25) | 0.86 (0.51, 1.43) | 0.68 (0.41, 1.14) | 0.83 (0.49, 1.40) |

| PFNA | 0.89 (0.73, 1.09) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.06) | 0.62 (0.38, 1.01) | 0.79 (0.47, 1.32) | 0.57 (0.34, 0.94) | 0.74 (0.44, 1.25) |

| PFOSA | 0.72 (0.49, 1.06) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.09) | 0.35 (0.06, 1.98) | NA | 0.36 (0.06, 2.05) | NA |

| PFOS | 0.85 (0.69, 1.04) | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) | 0.66 (0.39, 1.10) | 0.87 (0.54, 1.41) | 0.60 (0.35, 1.03) | 0.81 (0.50, 1.33) |

| PFOA | 0.97 (0.79, 1.18) | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) | 0.90 (0.54, 1.49) | 1.43 (0.89, 2.31) | 0.83 (0.48, 1.44) | 1.40 (0.85, 2.31) |

NOTE: Serum PFAS concentrations were log transformed and rescaled by their standard deviation for analysis when analyzed continuously. Concentrations for 12 women with insufficient serum for analysis were imputed.

Adjusted for age (continuous), BMI (categorical), prior pregnancy loss conditional on previous pregnancy (no prior pregnancy, previously pregnant without loss, previously pregnant with loss), any alcohol consumption during pregnancy (yes/no), and any cigarette smoking during pregnancy (yes/no).

NA, not appropriate for analysis as 2nd tertile is same as first tertile of zero after rounding.

2-N-ethyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamide acetate (Et-PFOSA-AcOH),

2-N-methyl-perfluorooctane sulfonamide acetate (Me-PFOSA-AcOH)

perfluorodecanoate (PFDeA)

perfluorononanoate (PFNA)

perfluorooctane sulfonamide (PFOSA)

perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)

perfluorooctanoate (PFOA)

p<0.05 before rounding, p=0.0482

1.4 Discussion

In the first cohort study with preconception serum measurement of 7 PFASs and daily follow-up of women to identify hCG pregnancies commencing at approximately 2 weeks post-conception, we observed no association between any chemicals in this class of compounds and increased risk of pregnancy loss. While most HRs were below one irrespective of whether they were modeled continuously or in tertiles, two were significantly associated with significant reductions in risk, i.e., Me-PFOSA-AcOH and PFNA. Given the uncertainty and divergent thinking about the inclusion of gravidity or parity in models as previously discussed (39), we repeated the analysis without prior history of loss conditional on parity variable and observed consistent findings. Specifically, little change was observed in the HRs for either Me-PFOSA-AcOH when modeled with or without it (0.79; 95% CI 0.62, 1.00 and 0.78; 95% CI 0.62, 0.99, respectively) or PFNA (0.57; 95% CI 0.34, 0.94 and 0.58; 95% CI 0.35, 0.95). Still, extreme caution is needed when interpreting the findings for Me-PFOSA-AcOH, as 97% of concentrations were below laboratory limits of detection. PFOSA is a precursor compound of PFOS, which may be one reason why it is not widely detected in people. Conversely, all but 2% of women had PFNA concentrations above the LOD with an observed 43% reduction in risk of pregnancy loss when comparing women in the highest versus lowest tertiles. This finding is in sharp contrast to an odds ratio of 16.5 (95% CI 7.39, 36.63) reported for PFNA in the Danish Odense Child Cohort Study when concentrations were modeled continuously using a case-cohort type of analysis [28]. While serum concentrations were similar for the two studies, important differences exist including our prospective ascertainment of both pregnancies (n=344) and losses (n=98) and having preconception measurement of PFASs for women. The Danish study was within a larger pregnancy cohort study that restricted women to those with PFASs measured before 12 weeks gestation and for whom miscarriages occurred before 22 weeks gestation (n=56). The comparison group comprised a random sample of women giving birth (n=336), followed by a matched case-control analysis. While our findings do not support those reported in this study, they are in general agreement with findings from the C8 Health Project, a residential community exposed to PFASs via contaminated drinking water. Of note is the considerably higher (28%) incidence of loss in our study than that reported in the former study (range 12%-22%) [23-26], most likely a reflection of our preconception cohort design and daily monitoring of pregnancy and ensuing losses rather than relying on self reported loss. Our incidence of pregnancy was based upon sensitive digital home pregnancy tests is remarkably similar (25% to 31%) to that reported in earlier preconception cohort studies that relied on daily urine testing for hormonal profiles and incident pregnancy loss (41-43). As such, our findings are not likely to be systematically affected by under-ascertainment of post-implantation pregnancies or losses. We recognize we are unable to assess PFASs and pre-implantation loss, given our cohort was not undergoing assisted reproductive technologies where fertilization and implantation can be measured. Currently, there are no biomarkers for either conception or implantation suitable for population-based research.

While we find no evidence of an adverse relation between any of the 7 PFASs and pregnancy loss in our cohort study, it is important to interpret the findings within the continuum of human fecundity. We are aware of research suggesting that specific PFASs such as PFOSA and PFNA are associated with newly diagnosed endometriosis [44], a gynecologic condition associated with infertility [45], and with a longer TTP or infertility as described above [14,15,46]. If PFASs are indeed associated with gynecologic disorders and/or a longer TTP, it remains possible that only the least exposed women will become pregnant making is more challenging to observe a relation between exposure and pregnancy loss. However, only the median PFOSA concentration differed significantly for women achieving pregnancy or not (infertile) in our cohort, but the absolute differences are small given the high percentage of concentrations below LOQ. Of note is our earlier report that PFOSA was positively associated with a longer TPP (14). Still it remains possible that PFOSA reduces the probability of pregnancy without impacting its continuation once established.

There are important limitations that need to be weighed when interpreting our findings beyond potential type II errors or residual confounding. Other notable limitations include the relatively small number of PFASs quantified for analysis albeit larger than published work, and our assessment of individual compounds rather than mixture-based approaches. In light of evolving methods for the analysis of mixtures coupled with very few data focusing on this specific study question, we specifically sought to explore each PFAS relative to pregnancy loss. Model specification is another important consideration and we strove for parsimonious models supported by biology, to the extent possible. This included adjustment for age, measured BMI, prospectively measured alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking during pregnancy, and prior history of pregnancy loss modeled as a function of past pregnancy history rather than simply modeling parity as a dichotomy (nulliparous versus parous). The reason being is that nulliparous women comprise two potentially distinct groups of women, particularly if PFASs affect pregnancy probabilities: 1) women who have never been pregnant and 2) women with previous pregnancies but no live births. We believe these are potentially different groups of women and such differences require conditioning on pregnancy history to distinguish an informative from a non-informative history.

The available data focusing on the relation between PFASs and pregnancy loss is insufficient at this time to definitively determine whether they are potential reproductive or developmental toxicants. Future research designed for preconception enrollment of women/couples who are prospectively followed throughout pregnancy is needed if we are to more completely answer this question and to do so within the context of couples’ complete reproductive performance, viz., is risk consistent across pregnancies. This strategy also will help inform about competing risk scenarios where infertility prevents pregnancy which is a necessary criterion for loss, in providing empirical data to aid model specification particularly related to prior reproductive performance, and in delineating the toxicokinetics of these compounds during sensitive windows of human development. Ultimately, such research will help to develop empirically supported risk communication. As noted in the recent Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances, the ubiquitous nature of PFASs reflecting their environmental persistence and bioaccumulation supports the need for research to fill critical data gaps [47].

1.5 Conclusions

We found no evidence of an adverse relation between any of the 7 PFASs under study and pregnancy loss. The extent to which the findings reflect the exclusion of exposed women who are unable to achieve pregnancy remain to be established.

Highlights.

Incidence of hCG pregnancy loss was 28%.

7 PFASs were measured women’s serum upon enrollment.

None of the 7 PFASs were associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss.

PFNA and Me-PFOSA-AcOH were associated with a significant reduction in risk.

Acknowledgements

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (#N01-HD-3-3355; N01-HD-3-3356; NOH-HD-3-3358). We acknowledge the technical assistance of Antonia Calafat, Division of Laboratory Sciences, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who performed the analytic chemistry work under a Memo of Understanding with the NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Key BD, Howell RD, Criddle CS. Fluorinated organic in the biosphere. Environ. Sci Technol. 1997;31:2445–2454. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prescher D, Gross U, Wotzka J, et al. Environmental behavior of fluoro surfactants: Part 2: Study on biochemical degradability. Acta Hydrochim Hydrobiol. 1985;13:17–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renner R. Growing concern over perfluorinated chemicals. Environ. Sci Technol. 2001;35:154A–160A. doi: 10.1021/es012317k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seacat AM, Thomford PJ, Hansen KJ, et al. Subchronic toxicity studies on perfluorooctanesulfonate potassium salt in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Toxicol Sci. 2002;68:249–264. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.249. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/68.1.249 doi: 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: terminology, classification, and origins. Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2011;7(4):513–541. doi: 10.1002/ieam.258. doi:10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giesy JP, Kannan K. Global distribution of perfluorooctane sulfonate in wildlife. Envrion Sci Technol. 2001;35:1339–1342. doi: 10.1021/es001834k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen KJ, Clemen LA, Ellefson ME, Johnson HO. Compound-specific quantitative characterization of organic fluorochemicals in biological matrices. Environ Sci Technol. 2001;35:766–770. doi: 10.1021/es001489z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olsen GW, Burris JM, Ehresman DJ, et al. Half-life of serum elimination of perfluorooctanesulfonate, perfluorohexanesulfonate, and perfluorooctanoate in retired fluorochemical production workers. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:1298–1305. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10009. doi:10.1289/ehp10009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau C, Butenhoff JL, Rogers JM. The developmental toxicity of perfluoroalkyl acids and their derivatives. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198(2):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.031. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Midasch O, Drexler H, Hart N, Beckmann MW, Angerer J. Transplacental exposure of neonates to perfluorooctane-sulfonate and perfluorooctanoate: a pilot study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2007;80(7):643–648. doi: 10.1007/s00420-006-0165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids: A review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicol Sci. 2007;99(2):366–394. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfm128. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bach CC, Bech BH, Brix N, et al. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances and human fetal growth: A systematic review. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2015;45(1):53–67. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2014.952400. doi:10.3109/10408444.2014.952400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vestergaard S, Nielsen F, Andersson A-M, et al. Association between perfluorinated compounds and time to pregnancy in a prospective cohort of Danish couples attempting to conceive. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(3):873–880. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der450. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buck Louis GM, Sundaram R, Schisterman EF, et al. Persistent environmental pollutants and couple fecundity: LIFE Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2013;121(2):231–236. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205301. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fei C, McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L, Olsen J. Maternal levels of perfluorinated chemicals and subfecundity. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(5):1200–1205. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den490. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vélez MP, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Maternal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals and reduced fecundity: the MIREC study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(3):701–709. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu350. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bach CC, Liew Z, Bech BH, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids and time to pregnancy revisited: an update from the Danish National Birth Cohort. 2015;14:59-1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12940-015-0040-9. doi:10.1186/s12940-015-0040-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bach CC, Bech BH, Nohr EA, et al. Serum perfluoroalkyl acids and time to pregnancy in nulliparous women. Environ Res. 2015;142:535–541. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.08.007. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joensen UN, Veyrand B, Antignac JP, et al. PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonate) in serum is negatively associated with testosterone levels, but not with semen quality, in healthy men. Hum reprod. 2013;28(3):599–608. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des425. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Specht IO, Hougaard KS, Spanò M, Bizzaro D, et al. Sperm DNA integrity in relation to exposure to environmental perfluoroalkyl substances – a study of spouses of pregnant women in three geographical regions. Reprod Toxicol. 2012;33(4):577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.02.008. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toft G, Jönsson BAG, Lindh CH, et al. Exposure to perfluorinated compounds and human semen quality in arctic and European populations. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(8):2532–2540. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des185. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buck Louis GM, Chen Z, Schisterman EF, et al. Perfluorochemicals and human semen quality: The LIFE Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(1):57–63. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307621. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stein CR, Savitz DA, Dougan M. Serum levels of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate and pregnancy outcome. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(7):837–846. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp212. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Savitz DA, Stein CR, Bartell SM, et al. Perfluorooctanoic acid exposure and pregnancy outcome in a highly exposed community. Epidemiol. 2012;23(3):386–392. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824cb93b. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31824cb93b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Savitz DA, Stein CR, Elston B, et al. Relationship of perfluorooctanoic acid exposure to pregnancy outcomes based on birth records in the Mid-Ohio Valley. Environ Health Perspect. 2012;120(8):1201–1207. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104752. doi:org/10.1289/ehp.1104752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Darrow LA, Howards PP, Winquist A, et al. PFOA and PFOS serum levels and miscarriage risk. Epidemiol. 2014;25(4):505–512. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000103. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buck Louis GM, Dukic VM, Heagerty PJ, et al. Statistical issues in modeling pregnancy outcome data. Stats Methods Med Res. 2006;15(2):103–126. doi: 10.1191/0962280206sm434oa. doi: 10.1191/0962280206sm434oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen TK, Andersen LB, Kyhl HB, et al. Association between perfluorinated compound exposure and miscarriage in Danish pregnant women. PLOS ONE. 2015:1–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123496. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buck Louis GM, Schisterman EF, Sweeney AM, et al. Designing prospective cohort studies for assessing reproductive and developmental toxicity during sensitive windows of human reproduction and development – the LIFE Study. Pediatr Perinatal Epidemiol. 2011;25(5):413–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01205.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lohman TG, Roche AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. H uman Kinetics Pub.; Champaign: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Behre HM, Kuhlage J, Gahner C, Sonntag B, Schem C, Schneider HP, et al. Prediction of ovulation by urinary hormone measurements with the home use ClearPlan® Fertility Monitor: comparison with transvaginal ultrasound scans and serum hormone measurements. Hum Reprod. 2000;15(12):2478–2482. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2478. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.12.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson S, Cushion M, Bond S, Godbert S, Pike J. Comparison of analytical sensitivity and women’s interpretation of home pregnancy tests. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2015;53(3):391–402. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0643. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2014-0643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato K, Wong LY, Jia LT, Kuklenyik Z, Calafat AM. Trends in exposure to polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: 1999-2008. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(19):8037–8045. doi: 10.1021/es1043613. doi: 10.1021/es1043613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuklenyik Z, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Measurement of 18 perfluorinated organic acids and amides in human serum using on-line solid-phase extraction. Anal Chem. 2005;77(18):6085–6091. doi: 10.1021/ac050671l. doi: 10.1021/ac050671l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox DR. Regression models and life-tables. JRSS, Series B (Methodological) 1972:187–200. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barrett ES, Thune I, Lipson SF, Furberg AS, Ellison PT. A factor analysis approach to examining relationships among ovarian steroid concentrations, gonadotrophin concentrations and menstrual cycle length characteristics in healthy, cycling women. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(3):801–811. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des429. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richardson DB, Ciampi A. Effects of exposure measurement error when an exposure variable is constrained by a lower limit. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(4):355–363. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf217. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schisterman EF, Vexler A, Whitcomb BW, Liu A. The limitations due to exposure detection limits for regression models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(4):374–383. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj039. doi.org/10.1093%2Faje%2Fkwj039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howards PP, Schisterman EF, Poole C, Kaufman JS, Weinberg CR. “Toward a clearer definition of confounding” revisited with directed acyclic graphs. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(6):506–511. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws127. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. Chapman and Hall; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. New Engl J Med. 1988;319(4):189–194. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807283190401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zinamen MJ, Clegg ED, Brown CC, O’Connor J, Selevan SG. Estimates of human fertility and pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 1996;65(3):503–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(3):577–84. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04694-0. doi.org/10.1016/S0015-0282(02)04694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Buck Louis GM, Peterson MC, Chen Z, et al. Perflurochemicals and Endometriosis: The ENDO Study. Epidemiol. 2012;23(6):799–805. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826cc0cf. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31826cc0cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peterson CM, Boiman Johnstone E, Hammoud AO, et al. Risk factors associated with endometriosis: importance of study population for characterizing disease – the ENDO Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;451:e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2013.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vélez MP, Arbuckle TE, Fraser WD. Maternal exposure to perfluorinated chemicals and reduced fecundity: the MIREC study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30(3):701–709. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu350. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Blum A, Balan SA, Scheringer M, et al. The Madrid Statement on poly- and perfluroalkyl substances (PFASs) Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(5):A107–A111. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1509934. doi.org/10.1289/ehp.1509934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]