Abstract

Following traumatic brain injury (TBI), activation of microglia and peripherally derived inflammatory macrophages occurs in association with tissue damage. This neuroinflammatory response may have beneficial or detrimental effects on neuronal survival, depending on the functional polarization of these cells along a continuum from M1-like to M2-like activation states. The mechanisms that regulate M1-like and M2-like activation after TBI are not well understood, but appear in part to reflect the redox state of the lesion microenvironment. NADPH oxidase (NOX2) is a critical enzyme system that generates reactive oxygen species in microglia/macrophages. After TBI, NOX2 is strongly up-regulated in M1-like, but not in M2-like polarized cells. Therefore, we hypothesized that NOX2 drives M1-like neuroinflammation and contributes to neurodegeneration and loss of neurological function after TBI. In the present studies we inhibited NOX2 activity using NOX2-knockout mice or the selective peptide inhibitor gp91ds-tat. We show that NOX2 is highly up-regulated in infiltrating macrophages after injury, and that NOX2 deficiency reduces markers of M1-like activation, limits tissue loss and neurodegeneration, and improves motor recovery after moderate-level control cortical injury (CCI). NOX2 deficiency also promotes M2-like activation after CCI, through increased IL-4Rα signaling in infiltrating macrophages, suggesting that NOX2 acts as a critical switch between M1- and M2-like activation states after TBI. Administration of gp91ds-tat to wild-type CCI mice starting at 24 hours post-injury reduces deficits in cognitive function and increased M2-like activation in the hippocampus. Collectively, our data indicate that increased NOX2 activity after TBI drives M1-like activation that contributes to inflammatory-mediated neurodegeneration, and that inhibiting this pathway provides neuroprotection, in part by altering M1-/M2-like balance towards the M2-like neuroinflammatory response.

Keywords: NADPH oxidase, NOX2, traumatic brain injury, microglia, macrophage, neuroinflammation, M1-/M2-like, neurodegeneration

Introduction

Recent experimental and clinical studies implicate neuroinflammation as a major contributor to chronic neurodegeneration and related neuropsychiatric dysfunction following single moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) or repetitive mild TBI (Aungst et al., 2014; Coughlin et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2013; Loane et al., 2014; Mouzon et al., 2014; Ramlackhansingh et al., 2011; Shitaka et al., 2011). TBI-induced inflammation involves both glial cells and infiltrating blood leukocytes (Ziebell and Morganti-Kossmann, 2010). Resident microglia and peripherally derived inflammatory macrophages migrate to the site of injury and release immunomodulatory factors. Microglial and macrophage activation involves multiple phenotypes with different physiological roles (Boche et al., 2013; Cherry et al., 2014; Gordon and Martinez, 2010); the differential functions reflect their composition of polarization markers ranging from M1-like to M2-like (Cherry et al., 2014; Perego et al., 2011). M1-like activation is characterized by up-regulation of pro-inflammatory mediators (e.g. TNFα, IL-1β, NOS2) and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are essential for host defense (Gordon and Martinez, 2010), but when highly activated or prolonged can contribute to injury and cause progressive tissue loss (Loane et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013). In contrast, M2-like activation is important for wound healing and resolving inflammation; it is marked by expression of factors such as arginase 1 (Arg1), Ym1, and Fizz 1, and release of neurotrophic factors that can promote tissue repair (Cherry et al., 2014). Although the mechanisms of the dysregulated M1-like neuroinflammatory response after TBI are not well understood, recent evidence has linked ROS from activated microglia to neuroinflammation-mediated oxidative stress and chronic neurodegeneration (Gao et al., 2012; Liao et al., 2012; Qin et al., 2013)

NADPH oxidase (NOX2) is a multi-subunit enzyme complex responsible for the production of both extracellular and intracellular ROS by phagocytes, including microglia and macrophages. Microglial NOX2 has been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple chronic neurodegenerative disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Choi et al., 2012; Shimohama et al., 2000), Parkinson’s disease (Wu et al., 2003), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) (Wu et al., 2006), and multiple sclerosis (Fischer et al., 2012; van Horssen et al., 2012). Microglial NOX2 activation can cause neurotoxicity, both through the production of extracellular ROS (Qin et al., 2004), as well as through initiation of redox signaling that amplifies the pro-inflammatory response (Mander and Brown, 2005; Pawate et al., 2004). NOX2 inhibition limits microglial ROS production and attenuates M1-like activation in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), reducing microglial-mediated neurotoxicity (Gao et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2013; Qin et al., 2004).

NOX2 is transiently up-regulated in injured neurons and hypertrophic astrocytes in the contused cortex after TBI (Dohi et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2015), and is highly expressed in reactive microglia/macrophages surrounding the expanding lesion for weeks and even months post-injury (Byrnes et al., 2012; Loane et al., 2014). Chronic microglial/macrophage NOX2 expression is associated with increased oxidative stress, progressive cortical and hippocampal neurodegeneration, and long-term cognitive impairments following TBI (Loane et al., 2014). Microglia/macrophages can change their activation state depending on the redox state of the microenvironment (Brune et al., 2013), and there is an age-related, NOX2-dependent shift in redox state towards an oxidizing environment that results in exaggerated M1-like activation and suppressed M2-like activation following TBI (Kumar et al., 2013). In injured cortex NOX2 is highly up-regulated in microglia/macrophages that co-express M1-like, or mixed M1-/M2-like activation markers, but not with single M2-like activation markers (Kumar et al., 2015). Increasingly, NOX2 is being recognized as an important therapeutic target for CNS injury (von Leden et al., 2016), and pharmacological or genetic intervention studies demonstrate that NOX2 inhibition after TBI is neuroprotective, mediated, in part, by targeting secondary neuroinflammation and microglial activation (Dohi et al., 2010; Loane et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012).

Here we set out to investigate cellular mechanisms that drive M1-like neuroinflammation and secondary neurodegeneration after TBI, and to establish the role of microglial/macrophage NOX2 in TBI pathology. The aims of the current study were to: (1) test the hypothesis that NOX2 drives M1-like neuroinflammation that contributes to neurodegeneration and loss of neurological function after TBI, and determine the relative role of NOX2 in peripheral macrophages versus resident microglia; (2) investigate cellular mechanisms that promote the alternative M2-like activation response after TBI in the absence of NOX2; and (3) determine if delayed systemic administration of a selective NOX2 peptide inhibitor improves outcomes after TBI by altering the M1-/M2-like neuroinflammatory responses.

Material and Methods

Animals

Studies were performed using either NOX2-deficient (NOX2−/−; B6.129S-Cybbtm1Din/J, stock 002365; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME,) adult male mice (10–12 week old, 22–26g), or age-matched C57Bl/6J (WT) male mice. Mice were housed in the Animal Care facility at the University of Maryland School of Medicine under a 12 hour light-dark cycle, with ad libitum access to food and water. All surgical procedures were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Maryland School Of Medicine.

Controlled cortical impact TBI model

Our custom-designed controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury device consists of a microprocessor-controlled pneumatic impactor with a 3.5 mm diameter tip. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane evaporated in a gas mixture containing 70% N2O and 30% O2 and administered through a nose mask (induction at 4% and maintenance at 2%). Depth of anesthesia was assessed by monitoring respiration rate and pedal withdrawal reflexes. Mice were placed on a heated pad, and core body temperature was maintained at 37°C. The head was mounted in a stereotaxic frame, and the surgical site was clipped and cleaned with Nolvasan and ethanol scrubs. A 10-mm midline incision was made over the skull, the skin and fascia were reflected, and a 4-mm craniotomy was made on the central aspect of the left parietal bone. The impounder tip of the injury device was then extended to its full stroke distance (44 mm), positioned to the surface of the exposed dura, and reset to impact the cortical surface. Moderate-level CCI was induced using an impactor velocity of 6 m/s and deformation depth of 2 mm as previously described (Fox et al., 1998; Loane et al., 2009). After injury, the incision was closed with interrupted 6-0 silk sutures, anesthesia was terminated, and the animal was placed into a heated cage to maintain normal core temperature for 45 minutes post-injury. The CCI model replicates several important secondary injury mechanisms after TBI, including apoptosis, edema, and secondary neuroinflammation (Byrnes et al., 2012; Piao et al., 2012), but does not produce acute intracranial hypertension. Sham animals underwent the same procedure as TBI mice except for the impact.

Study 1

Sham (n=6) and CCI (n=10) of WT and NOX2−/− mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) at 1 day post-injury and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml). Ipsilateral cortical tissue was rapidly dissected and snap-frozen on liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

Study 2

Sham (n=6) and CCI (n=6) of WT and NOX2−/− mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) at 3 day post-injury and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml). Ipsilateral cortical tissue was rapidly dissected and snap-frozen on liquid nitrogen for Western blotting.

Study 3

Sham (n=9) and CCI (n=9) of WT and NOX2−/− mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) at 3 days post-injury and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml). Ipsilateral cortical tissue was rapidly dissected and processed for CD11b positive selection and flow cytometry analysis. Ipsilateral cortical tissue from 3 mice were pooled for CD11b positive selection, and flow cytometry data represent 3 independent experiments.

Study 4

Sham (n=6) and CCI (n=6) of WT and NOX2−/− mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) at 1, 3, 7 and 28 days post-injury and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml), followed by 300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for histological analysis.

Study 5

Sham and CCI WT and NOX2−/− mice were used for behavioral studies (sham WT, n=6; sham NOX2−/− n=6; CCI WT, n=20; CCI NOX2−/− n=14). At 21 days post injury mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml), followed by 300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose and were processed for stereological based lesion volume and neuronal cell count analysis.

Study 6

A CCR2 antagonist, RS102895, was administered to WT and NOX2−/− mice starting at 36 hours prior to sham-injury (n=9) or CCI (n=9). Mice were treated with 2mg/kg RS102895 or equal volume vehicle (saline) by oral gavage every 12 hours (Matsubara et al., 2015) up until 24 hours post-injury. Mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml), and ipsilateral cortical tissue was rapidly dissected and processed for flow cytometry or snap-frozen on liquid nitrogen for RNA extraction.

Study 7

A selective NOX2 inhibitor, gp91ds-tat (5mg/kg), or equal concentration of ds-tat scrambled peptide (AnaSpec Inc. Fremont, CA) was delivered by intraperitoneal injection (I.P.) to WT CCI mice (n=8/group) starting at 1 day post-injury, with repeated I.P. administrations at 2 and 3 days post-injury. gp91ds-tat dosing was based on reported therapeutic effects in mice (Abais et al., 2013). ds-tat scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice underwent motor function testing (beam walk) on 1, 3, 5, and 7 days post-injury, and cognitive function testing (Y-maze) at 6 days post-injury. Mice were anesthetized (100 mg/kg sodium pentobarbital, I.P.) at 7 days post-injury and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 0.9% saline (100ml), followed by 300 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight, and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for histological analysis. A non-treated sham control group of WT mice (n=6) were used to establish baseline motor and cognitive function performance.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen sham-injured and TBI operated cortical tissue of WT and NOX2−/− mice using an RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with on-column DNase treatment (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). cDNA synthesis was performed on 1 μg of total RNA using a Verso cDNA RT kit (Thermo Scientific, Pittsburg, PA); the protocols used were according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan gene expression assays (TNFα, Mm00443258_m1; IL-1β, Mm01336189_m1; IL-12b, Mm00434174_m1; NOS2, Mm00440502_m1; IL-6, Mm00446190_m1; Ym1, Mm00657889_m1; Arg1, Mm00475988_m1; SOCS3, Mm00545913_s1; Fizz1, Mm00445109_m1; IL-1RN, Mm00446186_m1; IL-4Rα, Mm00446186_m1; NOX2, Mm01287743_m1; and GAPDH Mm99999915_g1;Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) on an ABI 7900 HT FAST Real Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems). Samples were assayed in duplicate in one run (40 cycles), which was composed of 3 stages, 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 sec for each cycle (denaturation) and finally the transcription step at 60°C for 1 min. Gene expression was calculated relative to the endogenous control sample (GAPDH) to determine relative expression values (2−ΔΔCt, where Ct is the threshold cycle).

Western blotting

Proteins from ipsilateral cortical tissue were extracted using RIPA buffer, equalized, and loaded onto 5–20% gradient gels for SDS PAGE (Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and then blocked overnight in 5 % milk in 1 × TBS containing 0.05 % Tween-20 (PBS-T). The membrane was incubated in mouse anti-arginase 1 (N-20) (1:1000; BD Transduction Laboratories), rabbit anti-Ym1 (1:1000; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC), or rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:2000; Sigma) overnight at 4°C, then washed three times in TBS-T, and incubated in appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA) for 2 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed three times in TBS-T, and proteins were visualized using SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Chemiluminescence was captured ChemiDoc™ XRS+ System (Bio-Rad), and protein bands were quantified by densitometric analysis using BioRad Molecular Imaging Software. The data presented reflects the intensity of target protein band normalized based on the intensity of the endogenous control for each sample (expressed in arbitrary units).

Isolation of CD11b-positive cells

A magnetic-bead conjugated anti-CD11b antibody was used to isolate microglia/macrophages from ipsilateral brain tissue of WT and NOX2−/− mice using MACS Separation technology (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA) as previously described (Kumar et al., 2015). Briefly, ipsilateral cortical and hippocampal tissue from sham-injured and CCI mice were rapidly microdisected and a single-cell suspension was prepared using enzymatic digestion (Neural Tissue Dissociation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec) in combination with a gentle MACS dissociator. Myelin was removed using Myelin Removal Beads II and LS columns (Miltenyi Biotec), and cells were incubated with CD11b microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec) and loaded onto a MS column (Miltenyi Biotec) placed in the magnetic field of a MACS separator. The negative fraction (flow through) was collected, and the column was washed three times with MACS buffer (Miltenyi Biotech). CD11b-positive cells were eluted by removing the magnetic field, resulting in the isolation of approximately 93% viable CD11b-positve cells from sham and TBI mice (data not shown).

Cell staining and flow cytometry

For intracellular staining CD11b-positive cells were incubated with protein transport inhibitor (BD Golgi Stop; BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), fixation and permeabilization solutions (Cytofix/Cytoperm Kit; BD Biosciences) as previously described (Kumar et al., 2015). The following antibodies were used: anti-mouse iNOS (1:50; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), anti-mouse arginase 1 (1:50, BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-rabbit Ym1 (1:50, Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada), and anti-mouse TGFβ (1:50, Biolegend), in combination with Alexa Fluor conjugated (488) secondary antibodies (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). 20,000 events were recorded using a BD FACSCanto II cytometer (BD Bioscience). Data was analyzed using FlowJo Software (v.X; TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR), and gating was determined based on appropriate negative isotype controls. SSC(A) and FSC(A) was used to identify mononuclear cell populations, and doublets/triplets were removed by SSC(A) and SSC(W) to yield single cell populations for subsequent analysis of M1/M2-like protein expression. In addition, cell populations were analyzed using SSC(W) (y axis) and M1/M2-like staining (x axis) to discriminate low versus high cell populations based on defined gates for sham control samples.

Staining of cell surface markers was performed using standard protocols. Briefly, CD11b-positive cells were resuspended in MACS buffer (Miltenyi Biotec), and stained using anti-CD11b-APC (1:10, Miltenyi Biotech), anti-CD45-FITC (1:10, Miltenyi Biotech), and anti-IL-4Rα-PE (1:50, Biolegend), or anti-F4/80-APC (1:50; Life technology) for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Cells were washed twice with 1ml of FACS buffer, fixed using 1% paraformaldehyde, and 20,000 events were recorded using a BD FACSCanto II cytometer (BD Bioscience). Gating was determined based on appropriate negative isotype controls. Infiltrating macrophage and resident microglial populations was determined by gating on CD11b+CD45hi or CD45hiF4/80hi (infiltrating macrophages), or CD11b+CD45lo (resident microglia) cells (Supplemental Figure 1) (Kumar et al., 2015; Stirling and Yong, 2008). IL-4Rα expression was measured in subsets of CD11b+CD45hi and CD11b+CD45lo cells. Data was analyzed using FlowJo Software (v.X; TreeStar, Inc., Ashland, OR).

Immunofluorescence imaging

20μm coronal brain sections of sham and CCI NOX2x+/+ and NOX2−/− mice from −1.70mm from bregma were selected and standard immunostaining techniques were employed. Briefly, 20μm brain sections were washed three times with 1 × PBS, blocked for 1 hour in goat serum containing 0.4% Triton X-100, and incubated overnight at 4°C with a combination of primary antibodies, including mouse anti-gp91phox (NOX2; 1:200, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-Clic1 (1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc, Dallas, TX), rat anti-CD68 (1:200, AbD Serotec Inc., Raleigh, NC), rat anti-CD11b (1:200, AbD Serotec Inc.), rabbit anti-P2Y12 (1:1000, Anaspec Inc., Fremont, CA), rat anti-F4/80 (1:300, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), rat anti-CD16/32 (1:1000, BD Biosciences), rabbit anti-Iba-1 (1:200; Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA). Sections were washed three times with 1 × PBS and incubated with appropriate Alexa Fluor conjugated secondary antibodies (Life Technologies) for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were washed three times with 1xPBS, counterstained with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1μg/ml, Sigma), and mounted with glass coverslips using Hydromount solution (National diagnostics, Atlanta, GA). Images were acquired using a fluorescent Nikon Ti-E inverted microscope, at 10× (Plan Apo 10X NA 0.45) or 20X (Plan APO 20X NA 0.75) magnification. Exposure times were kept constant for all sections in each experiment. All images were quantified using Nikon ND-Elements Software (AR 4.20.01), and co-localization of microglia/macrophage (Iba-1 or CD11b) marker analysis was performed by binary operation intersection followed by thresholding. 6,000–10,000 positive areas were quantified per mouse per experiment, and expression levels were expressed as binary area per region of interest (ROI) X106.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 60 μm coronal sections and standard immunostaining techniques were employed. Sections were incubated with rabbit anti-Ym1 (1:600, Stemcell Technologies Inc., Vancouver, BC), washed in 1 × PBS (3 times) and incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 hours at room temperature. Sections were incubated in avidin-biotin-horseradish peroxidase solution (Vectastain elite ABC kit, Vector Laboratories) for 1 hour and then reacted with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) for color development and mounted for immunohistochemical analysis using a Leica DM4000B microscope (Leica Microsystems, Exton, PA, USA).

Stereology

60μm coronal sections from NOX2x+/+ and NOX2−/− CCI mice were stained with cresyl violet (FD NeuroTechnologies, Baltimore, MD), dehydrated and mounted for analysis (n = 9/group).

Lesion volume was quantified based on the Cavalieri method of unbiased stereology using Stereoinvestigator Software (MBF Biosciences, Williston, VT) as previously described (Kumar et al., 2013). Briefly, the lesion volume was quantified by outlining the missing tissue on the injured hemisphere using the Cavalieri estimator with a grid spacing of 0.1 mm. Every eighth section from a total of 96 sections was analyzed beginning from a random start point.

Cresyl violet stained 60μm coronal sections were used to quantify neuronal densities in the ipsilateral cortex of sham and CCI mice. The optical fractionator method of stereology was employed as previously described (Kumar et al., 2015). Briefly, every fourth 60μm section between −1.22 and −2.54 mm from bregma was analyzed beginning from a random start point. A total of 5 sections were analyzed. The optical dissector had a size of 50 × 50 μm in the x-axis and the y-axis, respectively, with a height of 10μm and a guard zone of 4μm from the top of the section. The sampled region for cortex was demarcated in the injured hemisphere and cresyl violet stained neuronal cell bodies were counted using Stereoinvestigator Software (MBF Biosciences). The volume of the cortex was measured using the Cavalieri estimator method with a grid spacing of 50μm. The number of surviving neurons in each field was divided by the volume of the region of interest to obtain the cellular density expressed in counts/mm3.

Ym1 immunostained 60μm coronal sections were used to quantify Ym1-positive microglia/macrophages in the ipsilateral cortex of sham and CCI mice at 7 and 21 days post-injury. Two morphologically distinct Ym1-positive populations, ramified and amoeboid (bushy), were counted based on previously described morphological features (Byrnes et al., 2012). Briefly, every fourth section between −1.22 and −2.54 mm from bregma was analyzed beginning from a random start point. A total of 5 sections were analyzed. The sampled cortical region was demarcated in the ipsilateral hemisphere and Ym1-positive microglia/macrophages were counted using Stereoinvestigator Software (MBF Biosciences). The volume of the cortex was measured using the Cavalieri estimator method with a grid spacing of 50μm, and the number of Ym1-positive ramified and amoeboid cells was divided by the volume of the region of interest to obtain the cellular density expressed in cells/mm3. According to best stereological practice, all stereological probes were optimized to obtain a Gunderson coefficient of error (m = 1) value of less than 0.10 for the TBI tissue.

Beam walk

Motor function recovery was assessed using a beam walk test as previously described (Loane et al., 2009; Loane et al., 2013). The beam walk task discriminates fine motor coordination differences between sham and CCI mice. The test consists of a narrow wooden beam (5mm wide and 120mm in length), which is suspended 300 mm above a tabletop. Mice were placed on one end of the beam, and the number of foot faults of the right hind limb was recorded over 50 steps. Mice were trained on the beam walk for 3 days prior to CCI and tested through 7 or 21 days post-injury.

Y-maze spontaneous alternation

The Y-maze assesses spatial working memory, and takes advantage of the willingness of rodents to explore new environments, and was performed as previously described (Wu et al., 2014). Briefly, the Y-maze (Stoelting Co., Wood Dale, IL) consisted of three identical arms, each arm 35cm long, 5cm wide, and 10cm high, at an angle of 120° with respect to the other arms. One arm was randomly selected as the “start” arm, and the mouse was placed within and allowed to explore the maze freely for 5 minutes. Arm entries (arms A–C) were recorded by analyzing mouse activity using ANY-maze software (Stoelting Co.). An arm entry was attributed when all four paws of the mouse entered the arm, and an alternation was designated when the mouse entered three different arms consecutively. The percentage of alternation was calculated as follows: total alternations × 100/(total arm entries − 2). If a mouse scored significantly >50% alternations (the chance level for choosing the unfamiliar arm), this was indicative of spatial working memory.

Statistical analysis

Randomization and blinding was performed as follows: a) individuals performing animal surgery were blinded to genotype, b) individual who administered drugs was blinded to treatment group (vehicle vs gp91ds-tat), and c) stereological and behavioral analyses were performed by individuals blinded to genotype, injury or treatment groups. Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard errors of the mean (s.e.m.). Normality testing was performed and data sets passed normality (D’Agostino & Pearson omnibus normality test), and therefore parametric statistical analysis was performed. Motor function recovery was analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA to determine the interactions of post-injury trial and groups, followed by post-hoc adjustments using a Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test. qPCR, flow cytometry and stereological data were analyzed by one-way or two-way (injury × genotype) ANOVA, followed by post hoc adjustments using a Student Newman Keuls test. Remaining data were analyzed using a Student t test. Statistical analyses were performed using SigmaPlot 12 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) or GraphPad Prism Program, Version 3.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). A p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

NOX2 is robustly increased in CD68+ macrophages/microglia after TBI and contributes to chronic neurodegeneration and loss of neurological function

Oxidative stress and ROS production represent important secondary injury responses after TBI (Hall et al., 2012) that are mechanistically linked with microglia/macrophage activation and post-traumatic neuroinflammation. TBI rapidly up-regulates NOX2 enzyme subunits in injured neurons and astrocytes during the acute phase after injury, followed by high NOX2 expression in amoeboid-like microgila/macrophages during the sub-acute and chronic periods (Dohi et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2015; Loane et al., 2014). NOX2 inhibition by pharmacological or genetic means is neuroprotective (Dohi et al., 2010; Loane et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012), in part, by modulating secondary neuroinflammation and microglial activation. Previously, it has been shown that NOX2 deficiency resulted in reduced O2− and peroxynitrite metabolites in the injured cortex; effects that were associated with reduced neuronal cell death and microglial activation (Dohi et al., 2010). In the current study we set out to investigate cellular mechanisms that drive M1-like neuroinflammation and secondary neurodegeneration after TBI, and to establish the role of microglial/macrophage NOX2 in TBI pathology.

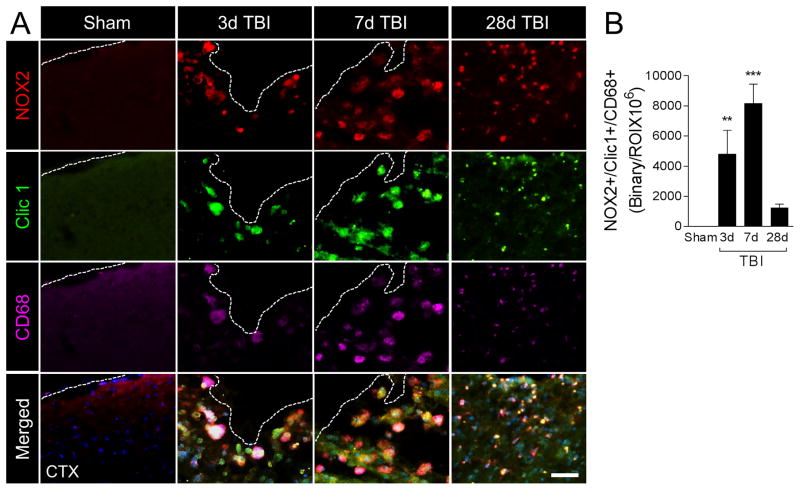

First, we evaluated active NOX2 in microglia/macrophages at 3, 7, and 28 days post-injury by colocalizing NOX2 with Clic1, an intracellular chloride channel that is required for charge compensation when active NOX2 transfers electrons across membranes to generate superoxide anions (Averaimo et al., 2010), and CD68. When compared with sham levels, TBI induced robust NOX2 expression in CD68+ cells that displayed amoeboid morphological features and also co-expressed Clic1 (Figure 1A). NOX2+/Clic1+/CD68+ cells were detected in the ipsilateral cortex within 3 days post-injury, with peak expression at 7 days post-injury (p<0.001 versus sham); expression levels declined thereafter, but failed to return to sham levels by 28 days post-injury (Figure 1B). NOX2+/Clic1+/CD68+ cells at 28 days post-injury had reduced cell body volume when compared to larger amoeboid-like cells detected at 3 and 7 days post-injury.

Figure 1. NOX2 is robustly increased in CD68-positive microglia/macrophages after moderate-level controlled cortical impact (CCI).

(A) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of sham and CCI WT mice at 3d, 7d and 28d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of NOX2 (red), Clic1 (green) and CD68 (magenta) demonstrate robust NOX2 expression in Clic1+/CD68+ microglia/macrophages after CCI, with peak expression at 7d post-injury in cells displaying amoeboid morphological features. Scale bar = 50μm. (B) Quantification of NOX2+/Clic1+/CD68+ colocalization after CCI. One-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/time point; **<0.01, and ***p<0.001 versus sham group.

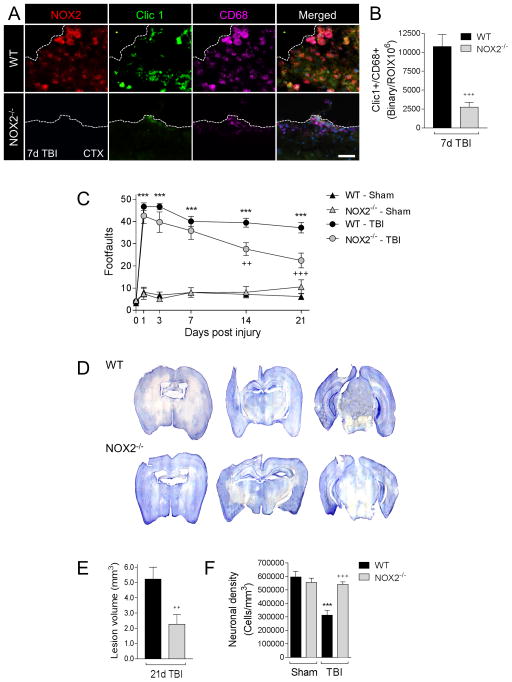

To investigate the effect of NOX2 inhibition on microglia/macrophage polarization, secondary neuroinflammation and chronic neurodegeneration after TBI we used a NOX2 knockout model (designated NOX2−/− (Pollock et al., 1995)). We assessed active NOX2 in CD68+ microglia/macrophages at 7 days post-injury in WT and NOX2−/− TBI mice to establish the impact of NOX2 deficiency on microglia/macrophage activation. As predicted, TBI in NOX2−/− mice resulted in significantly reduced Clic1 expression in CD68+ microglia/macrophages at 7 days post-injury (p<0.001 versus WT; Figure 2A,B), indicating reduced expression of ROS-producing microglia/macrophages in the ipsilateral cortex of NOX2−/− TBI mice when compared to WT TBI mice.

Figure 2. NOX2 deficiency reduces Clic1+/CD68+ expression, improves neurological recovery, and reduces cortical neurodegeneration after CCI.

(A) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 7d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of NOX2 (red), Clic1 (green) and CD68 (magenta) demonstrate absence of NOX2 in NOX2−/− CCI mice, and concomitant reduction in Clic1+/CD68+ expression. Scale bar = 50μm. (B) Quantification of Clic1+/CD68+ colocalization at 7d post-injury. Student’s t-test; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/time point; +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (C) Beam walk analysis of sham and CCI WT and NOX2−/− mice. In WT mice CCI induced persistent deficits in fine motor coordination through 21d post-injury. In contrast, NOX2−/− CCI mice had significantly reduced fine motor coordination deficits at 14d and 21d post-injury. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6–20/group; ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, and ++p<0.01 and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (D) Representative images of cresyl violet stained coronal sections from WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 21d post-injury. (E) Quantification of lesion volume in WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 21d post-injury. NOX2−/− resulted in a significant reduction in CCI lesion volume. Student’s t-test; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/group; ++p<0.01 versus WT CCI group. (F) Quantification of cortical neurodegeneration in WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 21d post-injury. In WT mice CCI resulted in significant loss of cortical neurons when compared to the WT sham group. In contrast, CCI in NOX2−/− mice resulted in reduced cortical neurodegeneration, which was significantly different to the WT CCI group. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/group; ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group.

In order to determine the long-term consequences of NOX2 inhibition after TBI we evaluated motor function recovery in sham and TBI WT and NOX2−/− mice, as well as cortical neurodegeneration at 21 days post-injury. First, we performed a beam walk task to assess deficits in fine-motor coordination up to 21 days post-injury. When compared to sham control mice, TBI resulted in significant motor function impairments in WT TBI mice, with 47 ± 2 footfaults (mean ± s.e.m.) at 1 day post-injury and persistent footfaults at 14 (39 ± 2) and 21 (37 ± 2) days post-injury (F(15,215)=14.36, p<0.0001; Figure 2C). In contrast, NOX2−/− TBI mice had improved motor performance and had significantly reduced number of footfaults at 14 (26 ± 3; p<0.01) and 21 days (22 ± 3; p<0.001) post-injury when compared with the WT TBI group. Next, we quantified TBI-induced lesion volume in the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− TBI mice at 21 days post-injury. TBI-induced lesion volume was significantly reduced in the NOX2−/− TBI group (2.26 ± 0.63 mm3) when compared to the WT TBI group (5.22 ± 0.78 mm3; Figure 2D,E). Finally, we quantified neuronal cell death in the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− TBI mice. TBI resulted in significant cortical neurodegeneration in the WT TBI group with 48% loss of neurons (312837 ± 37366 cells/mm3) when compared to sham-injured control levels (597280 ± 40467 cells/mm3; Figure 2F). When compared to the WT TBI group, cortical neurodegeneration was significantly reduced in the NOX2−/− TBI group (541487 ± 19046 cells/mm3; p<0.001 versus WT TBI group). Therefore, NOX2 deficiency results in significant improvements in motor function recovery and reduced neurodegeneration after TBI.

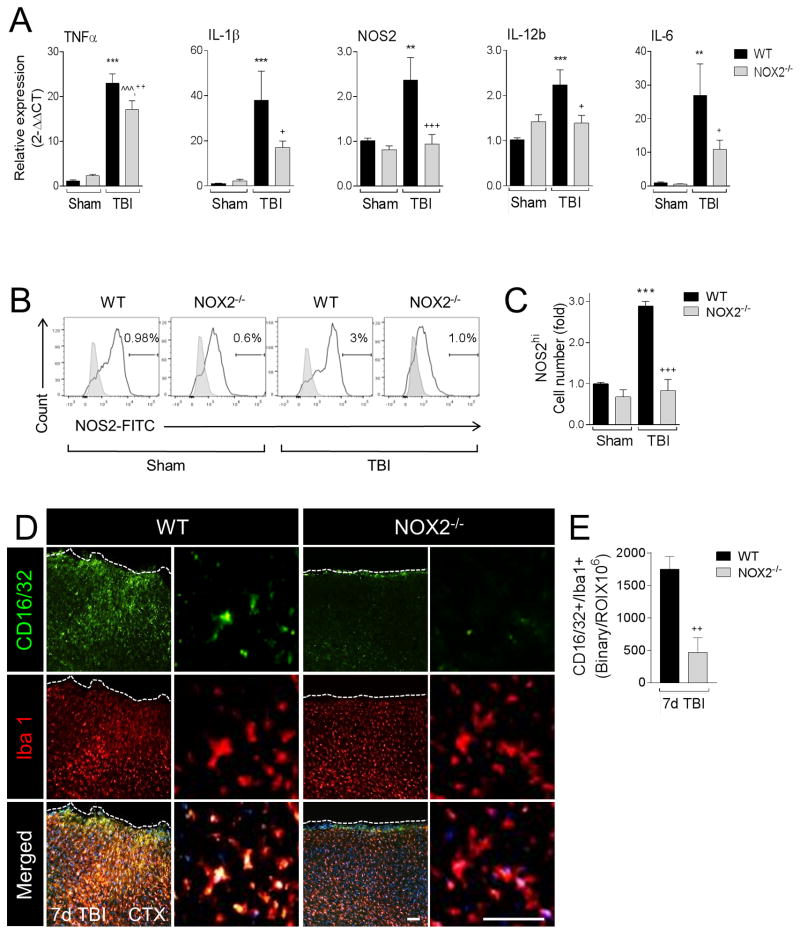

NOX2 deficiency reduces pro-inflammatory or M1-like activation of microglia/macrophages after TBI

Redox signaling is an essential component of the M1-like response in microglia and macrophages (Brune et al., 2013; Taetzsch et al., 2015), and NOX2 is thought to regulate polarization mechanisms in microglia (Choi et al., 2012). Recently, we demonstrated that NOX2 was up-regulated in CD68+ microglia/macrophages in the ipsilateral cortex at 7 days post-injury, and was co-localized with M1-like, or mixed M1-/M2-like activation markers, but never with single M2-like activation markers (Kumar et al., 2015). Therefore, we hypothesized that NOX2 drives a neurotoxic M1-like neuroinflammatory response after TBI. To test this hypothesis we isolated tissue from the contused cortex of WT and NOX2−/− TBI mice at 1 day postinjury to assess gene expression profiles for selected M1-like activation markers. TBI significantly increased mRNA levels of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12b, NOS2, and IL-6 in WT mice when compared with levels in sham controls (p<0.01 [NOS2, IL-6], p<0.001 [TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12b]; Figure 3A). In contrast, TBI in NOX2−/− mice resulted in a significant reduction of all M1-like mRNAs (p<0.05 [IL-6, IL-12b, IL-1β], p<0.001 [NOS2], p<0.01 [TNFα]), indicative of a reduced M1-like response in NOX2−/− TBI mice when compared with WT TBI mice. We then expanded our analysis to microglia/macrophages isolated from the TBI brain and performed flow cytometry for NOS2 as previously described (Kumar et al., 2015). When compared to sham levels there was a significant increase in NOS2 protein expression in isolated microglia/macrophages in WT TBI mice at 3 days post-injury (2-fold increase, p<0.01). There was no change in % of total NOS2+ cells after TBI (data not shown), but when we gated on the most highly activated cells with respect to sham control levels (NOS2hi population) there was a 3-fold increase in numbers of NOS2hi macrophages/microglia in WT TBI mice compared WT sham controls (p<0.001; Figure 3B,C). Notably, NOX2−/− significantly reduced the NOS2hi population induced by TBI (p<0.001 versus WT TBI) such that they were virtually indistinguishable from sham NOX2−/− control levels. Next, we performed in situ analysis for M1-like polarized microglia/macrophages in the ipsilateral cortex of TBI mice using CD16/32 as a marker of M1-like activation (Wang et al., 2013). TBI resulted in robust CD16/32 expression in Iba1+ microglia/macrophages in the injured cortex of WT mice at 7 days post-injury (Figure 3D,E). In contrast, there was diminished CD16/32 expression in NOX2−/− TBI mice, and significantly reduced CD16/32+/Iba1+ colocalization in NOX2−/− TBI mice when compared to WT TBI mice (p<0.01). Taken together, these data demonstrate that NOX2 deficiency mitigates the M1-like response after TBI.

Figure 3. NOX2 deficiency attenuates M1-like activation after CCI.

(A) qPCR analysis of M1-like activation genes in the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 1d post-injury. CCI-induced expression of M1-like activation genes, TNFα, IL-1β, NOS2, IL-12b, and IL-6 was significantly reduced in NOX2−/− CCI mice. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6–10/group; **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, ^^^p<0.001 versus NOX2−/− sham group, +p<0.01, ++p<0.01, and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of NOS2 protein expression in isolated microglia/macrophages from WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 3d post-injury. Representative histogram for NOS2 includes NOS2hi-gated populations. (C) Quantification of NOS2hi cell number. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments; ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (D) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 7d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of CD16/32 (green) and Iba1 (red) demonstrate reduced CD16/32 expression in Iba1+ microglia/macrophages in NOX2−/− CCI mice. Scale bars = 100μm (left) and 50μm (right). (E) Quantification of CD16/32+/Iba1+ colocalization at 7d post-injury. Student’s t-test; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/time point; ++p<0.01 versus WT CCI group.

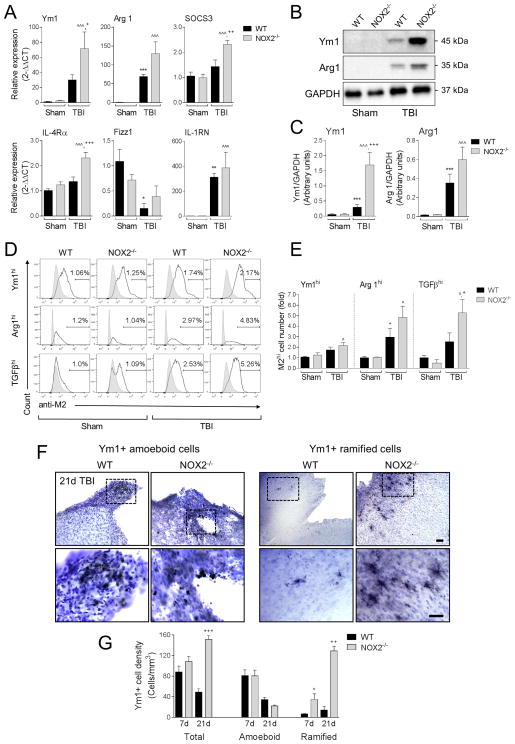

NOX2 deficiency promotes alternative or M2-like activation of microglia/macrophages after TBI

We next evaluated alternative or M2-like activation responses after TBI. mRNA analysis of M2-like markers in ipsilateral cortex at 1 day post-injury revealed that TBI significantly increased levels of Arg1 and IL-1RN, and trends in Ym1 and SOCS3 expression in WT mice when compared to levels in sham controls (p<0.01 [IL-1RN], p<0.001 [Arg 1]; Figure 4A). In addition, TBI significantly reduced the expression levels of Fizz1 in WT mice (p<0.05 versus WT sham control). TBI in NOX2−/− mice resulted in significantly increased expression levels of Ym1, SOCS3 and IL-4Rα mRNA (p<0.05 [Ym1], p<0.01 [SOCS3], and p<0.001 [IL-4Rα] versus WT TBI), and trends towards increased expression levels of Arg1 and IL-1RN, while the TBI-induced reduction of Fizz1 expression was diminished in NOX2−/− TBI mice. We also assessed Ym1 and Arg1 protein expression in ipsilateral cortex at 3 days post-injury and there was significantly increase Ym1 protein expression in NOX2−/− TBI mice when compared to WT TBI mice (p<0.001; Figure 4B,C), and trends towards increased Arg1 protein expression in this group. Next we isolated microglia/macrophages from the TBI brain and performed flow cytometry for Ym1, Arg1 and TGFβ (Figure 4D,E) (Kumar et al., 2015). When compared to sham-injured levels there was increased protein expression of Ym1, Arg1, and TGFβ, in isolated microglia/macrophages from WT TBI mice (Ym1 = 1.5-fold; TGFβ = 1.5-fold; and Arg1 = 2.0-fold increased versus WT sham group). There was no change in % of total Ym1+, TGFβ +, Arg1+ cells after TBI (data not shown), but when we gated on the most highly activated cells with respect to WT sham group, M2hi populations were increased 1.6-fold (Ym1hi), 2.9-fold (Arg1hi), and 2.5-fold (TGFβhi) in the WT TBI group, and further increased 2.0-fold (Ym1hi), 4.8-fold (Arg1hi), and 5.2-fold (TGFβhi) in the NOX2−/− TBI (Figure 4E). Notably, TBI in the NOX2−/− group resulted in significantly increased numbers of TGFβhi cells (p<0.05) when compared to WT TBI group, and there were trends towards increased numbers of Ym1hi and Arg1hi in the NOX2−/− TBI group.

Figure 4. NOX2 deficiency promotes M2-like activation after CCI.

(A) qPCR analysis of M2-like activation genes in the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 1d post-injury. CCI in WT mice increased expression of M2-like activation genes Ym1, Arg1, SOCS3, and IL-1RN, and decreased expression of Fizz1. Further, when compared to WT CCI mice, Ym1, SOCS3, IL-4Rα expression was significantly increased in NOX2−/− CCI mice. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6–10/group; *p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, ^p<0.05, and ^^^p<0.001 versus NOX2−/− sham group, and +<0.05, ++p<0.01, and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (B) Representative Western blots Ym1 and Arg1 in the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 3d post-injury. (C) Quantification of Ym1 and Arg1 protein expression. CCI in WT mice increased protein expression of Ym1 and Arg1. Further, when compared to WT CCI mice, Ym1 was significantly increased in NOX2−/− CCI mice. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/group; ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, ^^^p<0.001 versus NOX2−/− sham group, and +++p<0.001 versus WT CCI group. (D) Flow cytometry analysis of Ym1, Arg1, and TGFβ protein expression in isolated microglia/macrophages from WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 3d post-injury. Representative histogram for each M2-like marker includes M2hi-gated populations. (E) Quantification of M2hi cell number. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments; *p<0.05 versus WT sham group, ^p<0.05 versus NOX2−/− sham group, +p<0.05 versus WT CCI group. (F) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of WT and NOX2−/− CCI mice at 21d post-injury. Immunohistochemical analysis of Ym1 expression includes sub-classification of cells into Ym1+ amoeboid and Ym1+ ramified populations. Scale bar = 100μm (upper) and 50μm (lower). (G) Stereological analysis of Ym1+ cells at 7d and 21d post-injury, separated into total, amoeboid, and ramified populations. When compared to WT CCI mice, total Ym1+ cells was significantly increased in NOX2−/− CCI mice at 21d post-injury, and ramified Ym1+ cells was significantly increased at 7d and 21d post-injury. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 4–5/group; +<0.05 versus WT 7d ramified group, ++p<0.01 versus WT 21d ramified group, and +++p<0.001 21d total group.

Stereological assessment of Ym1+ cells in the ipsilateral cortex of TBI mice revealed that when compared to WT TBI mice there was a trend towards increased total Ym1+ cell number in NOX2−/− TBI mice at 7 days post-injury, and a significant increase in total Ym1+ cell number in NOX2−/− TBI mice at 21 days post-injury (p<0.001 versus WT TBI [21 days post-injury]; Figure 4F,G). Further breakdown of Ym1+ cells into morphologically distinct amoeboid and ramified populations revealed that there was no effect of genotype on the Ym1+ amoeboid populations at 7 or 21 days post-injury, but NOX2−/− TBI mice had significantly increased numbers of Ym1+ ramified cells at 7 and 21 days post-injury when compared to WT TBI mice (p<0.05 [7 days post-injury], p<0.01 [21 days post-injury]). Taken together, these experiments indicate that NOX2 inhibition via NOX2−/− promotes M2-like activation after TBI.

NOX2-positive brain macrophages rapidly accumulate in the TBI brain and contribute to M1-like neuroinflammation

TBI results in recruitment of peripheral macrophages (CCR2+F4/80hi or CD11b+CD45hi) into the ipsilateral cortex during the acute phase after injury (Hsieh et al., 2013; Hsieh et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2012; Morganti et al., 2015). Moreover, selective blockade of critical chemokine signaling (e.g. CCL2/CCR2) results in reduced macrophage infiltration and improves long-term neurological recovery after TBI (Hsieh et al., 2014; Israelsson et al., 2014; Morganti et al., 2015; Semple et al., 2010), indicating that the accumulation of macrophages in the TBI brain contributes to post-traumatic neuroinflammation and secondary neurodegeneration. To date the expression profile of the ROS-producing NOX2 enzyme after TBI has been evaluated using markers that fail to distinguish between resident microglia versus infiltrating brain macrophages. Therefore, we performed an in situ analysis of NOX2 expression in the ipsilateral cortex and hippocampus at various time points after TBI to address this shortcoming.

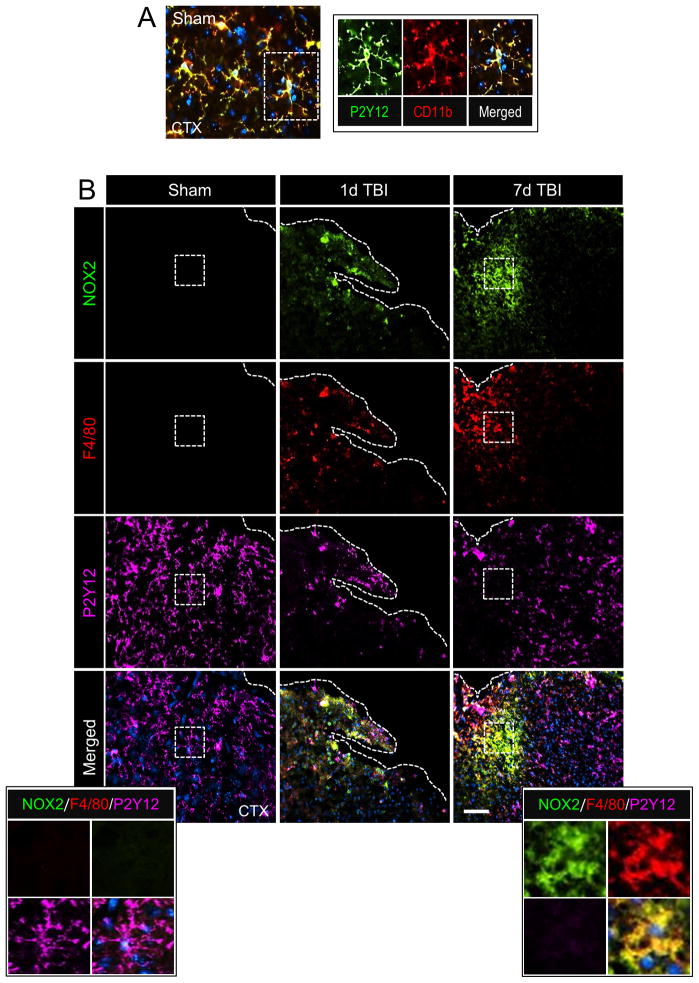

In order to analyze the relative expression of NOX2 in resident microglia versus infiltrating macrophages we performed colocalization studies using P2Y12 as a microglial-specific marker (Butovsky et al., 2014; Hickman et al., 2013) and F4/80 as a marker of infiltrating brain macrophages (Hsieh et al., 2013; Morganti et al., 2015). In the sham cortex there was high P2Y12 expression in cells that had ramified morphologies indicative of surveillant microglia (Figure 5A); P2Y12 was highly colocalized with CD11b+ resident microglia (Figure 5A inset). P2Y12+ cells in the sham cortex did not express NOX2 (Figure 5B), and F4/80+ brain macrophages were not detected in the sham brain (Figure 5B). Within 1 day of TBI NOX2 colocalized with F4/80+ cells, with minimal co-localization of NOX2 with P2Y12+ cells at this time point (Figure 5B,D). NOX2+/F4/80+ expression represented 25% of total NOX2+ expression in the cortex at 1 day post-injury, whereas NOX2+/P2Y12+ expression represented only 8% of total NOX2+ expression; remaining NOX2 expression was attributed to neurons at this time point (Kumar et al., 2015). Peak NOX2 expression occurred at 7 days post-injury (Figure 5B), with more than 2-fold co-expression of NOX2+/F4/80+ cells when compared to NOX2+/P2Y12+ cells (p<0.01; Figure 5D). At 7 day post-injury NOX2+/F4/80+ expression represented 60% of total NOX2+ expression, and NOX2+/P2Y12+ expression made up only 28% of total NOX2+ expression. Analysis of ipsilateral hippocampus revealed a similar pattern of expression. There was no NOX2 expression in the hippocampus at 1d post-injury (data not shown), but NOX2 was robustly increased in F4/80+ cells in the hippocampus at 7 days post-injury (Figure 5C). When compared to NOX2+/P2Y12+ cell expression in the hippocampus there was more than 3.7-fold increase in NOX2+/F4/80+ cells at 7 days post-injury (p<0.01; Figure 5D). These data indicate that in the immediate aftermath of TBI NOX2 is highly expressed on infiltrating F4/80+ brain macrophages, which rapidly accumulate within the injured cortex and significantly contribute to total NOX2+ expression at 7 days post-injury. NOX2 is also expressed in P2Y12+ microglia after TBI, but the expression kinetics in this cell population are delayed, and reduced, when compared to the infiltrating NOX2+/F4/80+ cell population.

Figure 5. NOX2-positive brain macrophages accumulate in the injured cortex after CCI.

(A) Representative image of resident microglia from the ipsilateral cortex of sham WT mice. Immunofluorescence analysis of P2Y12 (green) and CD11b (red) demonstrate colocalization of P2Y12 with CD11b in cells that have ramified morphologies indicative of surveillant microglia (inset). (B) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of sham and CCI WT mice at 1d and 7d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of NOX2 (green), F4/80 (red) and P2Y12 (magenta) demonstrate increased NOX2 expression in F4/80+ brain macrophages at 1d post-injury, with peak NOX2+/F4/80+ expression at 7d post-injury. There was low NOX2 expression in P2Y12+ microglia at 1d post-injury, and NOX2+/P2Y12+ expression at 7d post-injury was reduced when compared to NOX2+/F4/80+ expression. Scale bar = 50μm. Inset display high magnification images from the ipsilateral cortex of sham and 7d CCI mice. (C) Representative images from the hippocampus of sham and 7d post-injury WT mice. Immunofluorescence analysis of NOX2 (green), F4/80 (red) and P2Y12 (magenta) demonstrate increased NOX2 expression in F4/80+ brain macrophages at 7d postinjury. Scale bar = 50μm. Inset display high magnification images from the ipsilateral cortex of sham and 7d CCI mice. (D) Quantification of NOX2+/F4/80+ and NOX2+/P2Y12+ colocalization after CCI in the ipsilateral cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (HP). Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6/time point; *p<0.05, **<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus sham group, ++p<0.01 and +++p<0.001 versus NOX2+/F4/80+ at 7d.

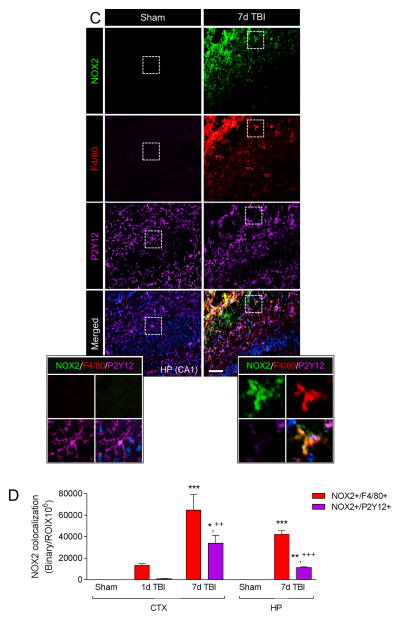

Next, we sought to determine if infiltrating NOX2+ macrophages contribute to M1-like neuroinflammation after TBI so we administered a CCR2 antagonist, RS102895 (Matsubara et al., 2015), to WT mice starting at 36 hours prior to sham or TBI. Mice were treated with 2mg/kg RS102895 or equal volume vehicle by oral gavage every 12 hours (Matsubara et al., 2015) up until 24 hours post-injury when ipsilateral cortex was isolated for flow cytometry or mRNA analysis (Figure 6A). Our flow cytometry analysis revealed that pre-treatment with RS102895 prior to TBI decreased accumulation of CD11b+CD45hiF4/80hi macrophages by 54% when compared to the vehicle-treated TBI group (Figure 6B), thereby indicating robust reduction of macrophage infiltration after TBI. Notably, gene expression analysis of ipsilateral cortical tissue demonstrated that RS102895 treatment significantly decreased the TBI-induced increase in NOX2 and TNFα mRNA (p<0.01 [NOX2] and p<0.05 [TNFα] versus vehicle-treated TBI group; Figure 6C). Taken together, these data indicate that NOX2+ macrophages rapidly accumulate in the injured cortex after TBI, and that CCR2 antagonisms can block the infiltration of NOX2+ macrophages and reduce M1-like neuroinflammation.

Figure 6. Blocking macrophage infiltration reduces NOX2 and TNFα expression after CCI.

(A) Experimental protocol to block macrophage accumulation after CCI. A CCR2 antagonist, RS102895 (2mg/kg; P.O.), was administered to WT mice starting at 36 hours prior to sham or CCI. (B) RS102895 pre-treatment blocks macrophage infiltration (CD11b+CD45hiF4/80hi cells) in the ipsilateral cortex following at 1d post-injury. Pre-treatment with RS102895 resulted in approximately 54% reduction of CD45hiF4/80hi cells in the ipsilateral cortex after CCI, demonstrating significantly reduced macrophage infiltration after injury. (C) qPCR analysis for NOX2 and TNFα in sham and CCI WT mice with/without RS102895 treatment. RS102895 significantly reduced the CCI-induced increase in NOX2 and TNFα expression at 1d post-injury. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 4–6/group; ***p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated sham group, #p<0.05 and ##p<0.01 versus vehicle-treated CCI group.

NOX2 deficiency increases IL-4Rα expression on infiltrating macrophages and CCR2 antagonism prevents induction of M2-like activation in NOX2−/− TBI mice

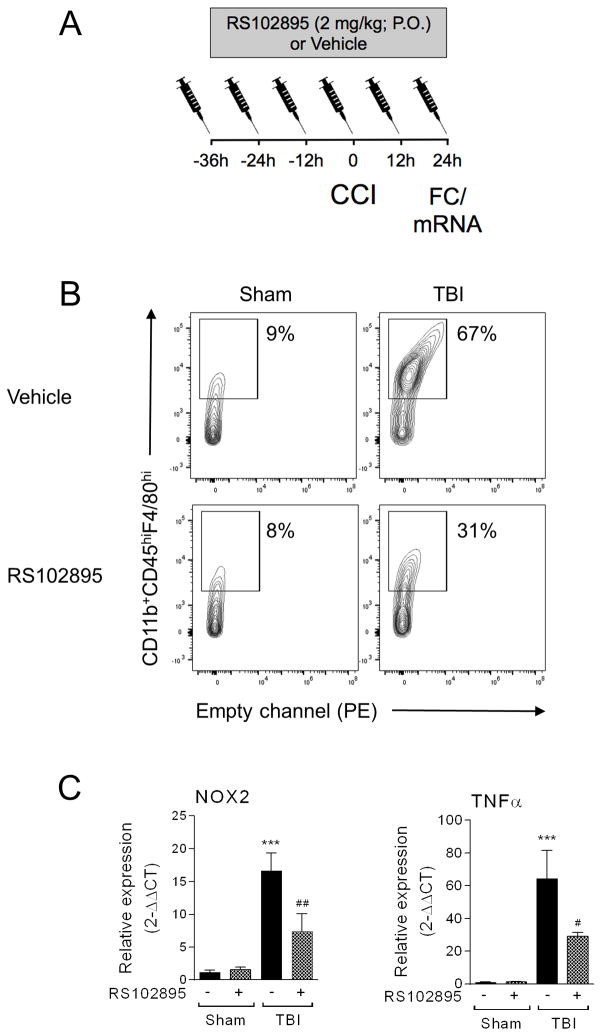

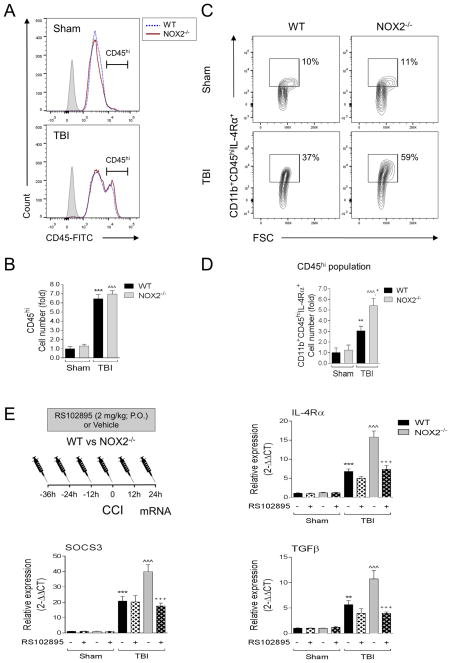

In order to determine the relative contribution of resident microglia versus infiltrating macrophages on NOX2-mediated alteration of M1-/M2-like balance after TBI we used flow cytometry to distinguish between microglial-specific (CD11b+CD45lo) and macrophage-specific (CD11b+CD45hi) effects in sham and TBI WT and NOX2−/− mice (see CD45 gating strategy in Supplemental Figure 1 (Kumar et al., 2015; Stirling and Yong, 2008)). When compared to sham control levels, TBI resulted in a significant increase in the number of CD45hi cells infiltrating the ipsilateral cortex in WT TBI mice at 3 days post-injury (p<0.001; Figure 7A,B). There was no genotype effect on CD45hi cell number after TBI, indicating that equal numbers of macrophages infiltrated the ipsilateral cortex in WT and NOX2−/− TBI mice.

Figure 7. NOX2 deficiency increases IL-4Rα expression in infiltrating macrophages, and RS102895 treatment blocks the induction of M2-like activation markers in NOX2 deficient CCI mice.

(A,B) Flow cytometry analysis of resident microglia (CD11b+CD45lo) versus infiltrating brain macrophages (CD11b+CD45hi) from WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 3d post-injury. (A) Representative histogram for CD45 includes CD45hi-gated populations, and (B) quantification of CD45hi cell number. WT and NOX2−/− CCI groups had equal numbers of CD11b+CD45hi cells at 3d post-injury. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments; ***p<0.001 versus WT sham group, and ^^^p<0.001 versus NOX2−/− sham group. (C,D) Flow cytometry analysis of IL-4Rα expression in CD11b+CD45hi from WT and NOX2−/− sham and CCI mice at 3d post-injury. Representative scatter plots (C) and histograms (D) for CD11b+CD45hiIL-4Rα+. There was a significant increase in IL-4Rα expression in the CD45hi (macrophage) population in NOX2−/− CCI mice. Two-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent experiments; **p<0.01 versus WT sham group, ^^^p<0.001 versus NOX2−/− sham group, and +p<0.05 versus WT CCI group. (E) Blocking macrophage infiltration alters M2-like expression in NOX2 deficient CCI mice. To block macrophage accumulation after CCI RS102895 (2mg/kg; P.O.) was administered to WT and NOX2−/− mice starting at 36 hours prior to sham or CCI. At 1d post-injury ipsilateral cortical tissue was collected for mRNA analysis. Analysis of IL-4Rα, SOCS3, and TGFβ mRNA in sham and CCI from WT and NOX2−/− mice with/without RS102895 treatment. RS102895 treatment reduced the CCI-induced increase in IL-4Rα, SCOS3 and TGFβ expression in NOX2−/− CCI mice. One-way ANOVA with Student Newman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 4–6/group; **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated WT sham group, ^^^p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated NOX2−/− sham group, and +++p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated NOX2−/− CCI group.

IL-4 induces alternative M2-like activation in microglia and macrophages (Colton, 2009; Gordon and Martinez, 2010), and IL-4Rα is up-regulated after TBI (Kumar et al., 2015), with peak expression occurring at 3 days post-injury. We therefore sought to assess IL-4Rα expression in WT and NOX2−/− sham and TBI mice at 3 days post-injury, and analyzed microglial-specific (CD11b+CD45lo) versus macrophage-specific (CD11b+CD45hi) expression patterns. There was a small, albeit significant, increase in IL-4Rα in CD45lo cells in WT TBI mice when compared to sham controls (p<0.05; data not shown); however, there was no genotype effect on CD45loIL-4Rα+ cell number after TBI. Analysis of the CD45hiIL-4Rα+ cell population revealed that there was a significant increase in CD45hiIL-4Rα+ cell number in WT TBI mice when compared to sham controls (p<0.01), and NOX2−/− resulted in a significant increase in CD45hiIL-4Rα+ cells after TBI when compared with WT TBI group (p<0.05) (Figure 7C,D). These data indicate that in NOX2−/− TBI mice there is increased IL-4Rα expression in infiltrating macrophages (CD45hiIL-4Rα+ cells).

We next administered RS102895 to WT and NOX2−/− mice starting at 36 hours prior to sham or TBI as previously described (Figure 7E), and assessed M2-like activation markers in ipsilateral cortex of sham and TBI WT and NOX2−/− mice that were treated with RS102895 or vehicle. As predicted, in the vehicle-treated control groups, TBI in NOX2−/− mice resulted in a significant increase in IL-4Rα, SOCS3, and TGFβ expression when compared to WT TBI mice (p<0.001; Figure 7E). The NOX2−/−-mediated up-regulation of each M2-like activation marker was significantly reduced with RS102895 treatment (p<0.001 versus vehicle-treated NOX2−/− TBI group), such that the RS102895-treated NOX2−/− TBI group returned to vehicle-treated WT TBI levels. Taken together, these studies indicate that the M2-like neuroinflammatory response in NOX2−/− TBI mice is mediated, in part, by infiltration of IL-4Rα+ macrophages into the ipsilateral cortex.

Delayed systemic administration of a NOX2 inhibitor, gp91ds-tat, promotes M2-like activation and improves spatial working memory after TBI

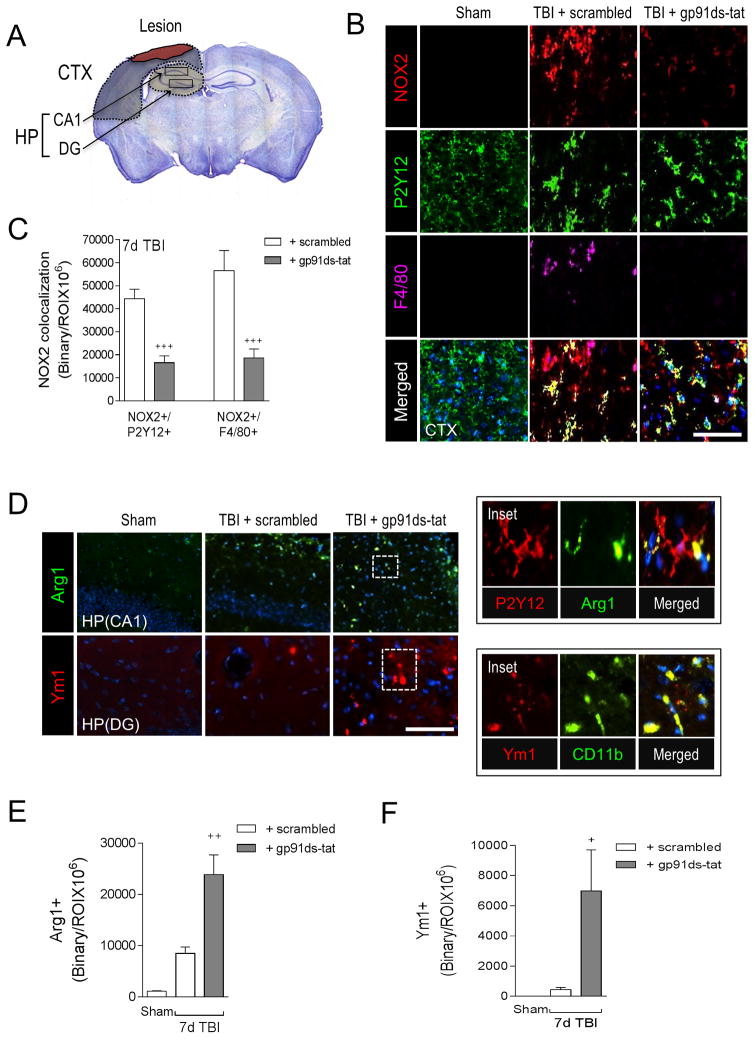

In order to explore the therapeutic potential of targeting NOX2-mediated neuroinflammation after TBI we sought to inhibit NOX2 using a specific peptide inhibitor, gp91ds-tat (Rey et al., 2001), and a delayed and clinically relevant drug treatment protocol. We delivered gp91ds-tat (5 mg/kg) or equal concentration of ds-tat scrambled peptide by intraperitoneal injection to TBI mice starting at 1 day post-injury, with repeat dosing at 2 and 3 days post-injury, and then performed motor and cognitive function tests prior to euthanasia at 7 days post-injury for histological assessments. We analyzed NOX2 expression in microglia (P2Y12+) and macrophages (F4/80+) in peri-lesional cortex and hippocampus (Figure 8A) at 7 days post-injury, and demonstrated that when compared to scramble-treated TBI group, gp91ds-tat treatment significantly reduced NOX2+/P2Y12+ and NOX2+/F4/80+ expression following TBI (p<0.001 for both; Figure 8B,C). Next, we evaluated microglial/macrophage activation in the hippocampus of TBI mice using Arg1 and Ym1 as markers of M2-like polarized cells. When compared to sham-injured controls, TBI increased Arg1 and Ym1 expression in the hippocampus (Figure 8D,E,F). Moreover, gp91ds-tat treatment significantly increased Arg1 (p<0.01 versus TBI + scrambled; Figure 8D,E) and Ym1 (p<0.05 versus TBI + scrambled; Figure 8D,F) expression in the hippocampus after TBI. Further analysis confirmed that Arg1 co-localized with P2Y12 and Ym1 colocalized with CD11b in the hippocampus (Figure 8D insets).

Figure 8. A selective NOX2 peptide inhibitor, gp91ds-tat, promotes M2-like activation after CCI.

(A) Image analysis was performed in the peri-lesional cortex (CTX) and hippocampus (HP) at −2.06mm from bregma as outlined. (B) Representative images from the ipsilateral cortex of sham, scrambled- or gp91ds-tat- treated CCI mice at 7d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of NOX2 (red), P2Y12 (green), and F4/80 (magenta) demonstrate that gp91ds-tat treatment decreased NOX2 expression in P2Y12+ microglia and F4/80+ brain macrophages at 7d post-injury. Scale bar = 50μm. (C) Quantification of NOX2+/P2Y12+ and NOX2+/F4/80+ colocalization in the cortex of scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice. gp91ds-tat treatment significantly reduced NOX2+/P2Y12+ and NOX2+/F4/80+ expression after CCI. Student’s t-test; data = mean ± SEM; n = 5/time point; +++p<0.001 versus scrambled-treated CCI group. (D) Representative images from the ipsilateral hippocampus of scrambled- or gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice at 7d post-injury. Immunofluorescence analysis of Arg1 (green) and Ym1 (red) demonstrates that gp91ds-tat treatment increased Arg 1 and Ym1 expression in the hippocampus at 7d post-injury. Scale bar = 50μm. Inset demonstrates that within the injured hippocampus Arg1 (green) colocalized with P2Y12 (red) cells, and Ym1 (red) colocalized with and CD11b (green) cells. (E, F) Quantification of Arg1+ and Ym1+ cells in the hippocampus of scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice. Student’s t-test; data = mean ± SEM; n = 5/time point; +p<0.05 versus scrambled-treated CCI group.

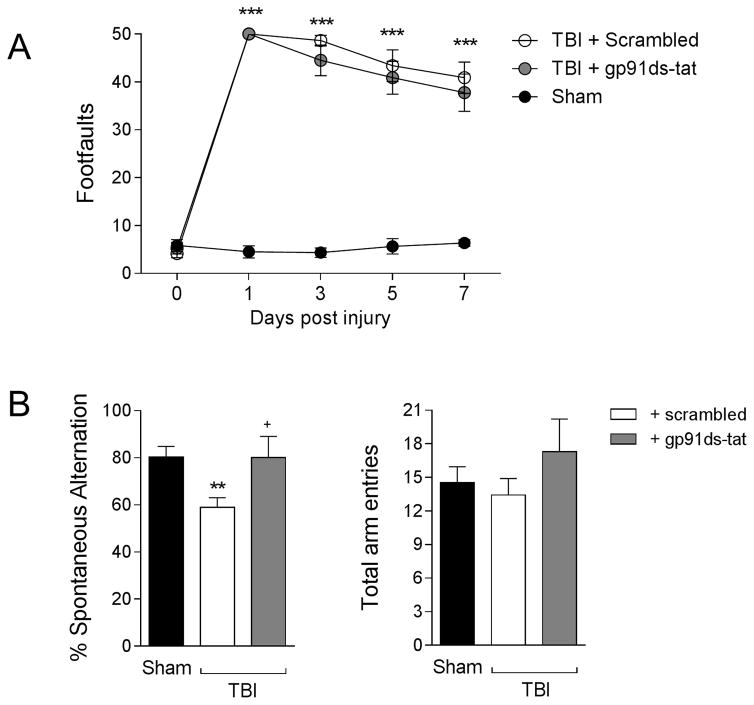

Finally, to determine the consequence of increased M2-like activation due to gp91ds-tat treatment, we assessed motor and cognitive function recovery using beam walk and Y maze tasks, respectively. First, we performed beam walk to assess deficits in fine-motor coordination up to 7 days post-injury. When compared to sham control mice, TBI resulted in significant motor function impairments in scrambled-treated TBI mice, with 50 ± 0 footfaults (mean ± s.e.m.) at 1 day post-injury and persistent footfaults through 7 (41 ± 3) days post-injury (F(8,95)=19.90, p<0.0001); Figure 9A). gp91ds-tat treatment failed to improve deficits in fine motor coordination during the sub-acute period post-injury, and gp91ds-tat-treated TBI mice had equal number of footfaults at 7 (38 ± 4) days post-injury. We then assessed hippocampal-dependent spatial working memory using a Y maze test. Sham mice showed 80.4 ± 4.4% spontaneous alteration, indicative of functional working memory, whereas scrambled-treated TBI mice had deficits that resulted in significantly reduced spontaneous alternation behavior (58.9 ± 3.7%; p<0.01 versus sham group, Figure 9B). In contrast, gp91ds-tat-treated TBI mice showed significantly increased spontaneous alternation (80.2 ± 3.7%) when compared to the scrambled-treated TBI group (p<0.05). All groups of mice had equivalent total arm entries during this test. Taken together, our pharmacological studies demonstrate that when we target NOX2 after TBI using a selective peptide inhibitor and a delayed systemic administration protocol we reduce NOX2 expression in microglia/macrophages, promote M2-like activation in the hippocampus, and ameliorate TBI-induced deficits in spatial working memory.

Figure 9. gp91ds-tat treatment improves cognitive function recovery after CCI.

(A) Beam walk analysis in sham, scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice. In scrambled- and gp91ds-tattreated mice, CCI induced persistent deficits in fine motor coordination through 7d post-injury. There was no difference between scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated mice in this motor coordination task. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6–8/group; ***p<0.001 versus sham group. (B) Y maze analysis for spatial working memory in sham, scrambled- and gp91ds-tat-treated CCI mice at 6d post-injury. CCI significantly reduced % spontaneous alternation in scrambled-treated CCI mice when compared to the sham group. In contrast, gp91ds-tat treatment ameliorated CCI-induced deficits, and the gp91ds-tat-treated group had equal % spontaneous alternation as the sham group. One-way ANOVA with Student Neuman Keuls correction for multiple comparisons; data = mean ± SEM; n = 6–8/group; **p<0.01 versus sham group, and +p<0.05 versus scrambled-treated CCI group.

Discussion

NOX2 is a key mechanism of microglial-mediated neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease (Lull and Block, 2010). NOX2 activation has been shown to contribute to secondary injury after ischemic brain injury (Chen et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2009), spinal cord injury (Khayrullina et al., 2015), and TBI (Byrnes et al., 2012; Dohi et al., 2010; Loane et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2012). After experimental TBI, NOX2 is chronically up-regulated in CD68+ microglia/macrophages in the peri-lesional cortex up to 12 months post-injury (Loane et al., 2014). Here we demonstrate that NOX2 is robustly up-regulated in ROS-producing microglia/macrophages after TBI, with peak NOX2 expression at 7 days post-injury in cells displaying amoeboid morphologies characteristics of peripheral monocytes. These data support prior studies that showed NOX2 to be highly up-regulated in microglia after TBI, and that NOX2 deficiency reduced oxidative stress and neuronal cell death in the injured cortex (Dohi et al., 2010).

Accumulation of peripherally derived inflammatory macrophages can contribute to neuroinflammation after TBI (Hsieh et al., 2014; Israelsson et al., 2014; Morganti et al., 2015; Semple et al., 2010), with a marked accumulation of inflammatory macrophages (CD11b+CD45hi, CCR2+F4/80hi) in injured cortex within 24 hours (Hsieh et al., 2013; Hsieh et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2015; Morganti et al., 2015). Moreover, inhibiting CCL2/CCR2 signaling reduces macrophage infiltration, attenuates secondary neuroinflammation and improves neurological function after TBI (Hsieh et al., 2014; Israelsson et al., 2014; Morganti et al., 2015; Semple et al., 2010). We compared NOX2 expression in resident microglia versus infiltrating macrophages using P2Y12 (Butovsky et al., 2014; Hickman et al., 2013) and F4/80 (Hsieh et al., 2013; Morganti et al., 2015) as markers of resident and infiltrating cells, respectively. NOX2 was expressed in F4/80+ macrophages that accumulated within the injured cortex at 1 day post-injury; these cells predominated the injured cortex at 7 days post-injury, with more than twice NOX2+/F4/80+ cells compared to NOX2+/P2Y12+ cells, indicating that the majority of NOX2 activation following TBI is mediated through the influx of F4/80+ macrophages. In support of this conclusion, blocking macrophage infiltration using the CCR2 antagonist, RS102895, significantly reduced NOX2 expression in injured cortex. Another CCR2 antagonist, CCX872, also was shown to limit TBI-induced up-regulation of NOX2 subunits in brain macrophages acutely isolated following CCI (Morganti et al., 2015). Furthermore, chimeric studies using NOX2−/− bone marrow transplanted into wild-type mice or wild-type bone marrow transplanted into NOX2−/− mice show that NOX2 from circulating cells contributes more to the exacerbation of ischemic injury compared to resident microglial cells (Tang et al., 2011). Collectively, these data indicate that persistent NOX2-dependent oxidative stress resulting from infiltrating monocytes is an important contributor to chronic inflammatory-mediated neurodegeneration following acute brain injury.

A major finding in our study was that targeting NOX2 after TBI alters M1-/M2-like balance towards the alternatively activated M2-like phenotype, supporting the conclusion that NOX2 activity promotes the M1-like activation of microglia/macrophages while repressing M2-like activation (Choi et al., 2012). Redox signaling is essential for M1-like activation of macrophages and microglia (Brune et al., 2013; Taetzsch et al., 2015), and NOX2 initiates redox signaling that amplifies the M1-like response (Mander and Brown, 2005; Pawate et al., 2004). Previously we demonstrated that NOX2 was co-localized with M1-like, or mixed M1-/M2-like activation markers after TBI, but not with M2-like only markers (Kumar et al., 2015). Prior studies by us showed an inverse relationship between increased NOX2 expression and M2-like activation in the aged TBI brain (Kumar et al., 2013). Here, using NOX2−/− mice we demonstrate that inhibition of NOX2 activity after TBI limits the expression of M1-like activation markers (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12, NOS2, IL-6 and CD16/32) through 7 days post-injury. Notably, the reduced M1-like activation profile in NOX2−/− TBI mice was associated with improved motor recovery and reduced neurodegeneration at 21 days post-injury. We also recently demonstrated that NOX2 inhibition by gp91ds-tat treatment resulted in significantly reduced CD16/32 expression and oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage following TBI (Kumar et al., 2015). These data indicate that increased NOX2 activity after TBI drives M1-like activation that contributes to chronic inflammatory-mediated neurodegeneration, and that inhibiting this pathway dampens deleterious M1-like responses and provides neuroprotection.

Importantly, in the absence of NOX2 microglia/macrophages exhibit an alternative M2-like activation profile after TBI. The M2-like phenotype is important for tissue repair, phagocytosis, and resolution of inflammation (Cherry et al., 2014). NOX2 deficiency or inhibition increased expression of M2-like markers during the acute phase after TBI; Arg1, SOCS3, and TGFβ were significantly up-regulated in isolated microglia/macrophages and/or tissue from the TBI brain in NOX2−/− TBI or gp91ds-tat treated TBI mice. Ym1 expression was also up-regulated in NOX2−/− TBI mice, and in situ analysis revealed significantly increased numbers of Ym1+ ramified cells at 21 days post-injury in NOX2−/− TBI mice compared to WT TBI mice, indicating increased expression in M2-like microglia. The phenotypic shift in NOX2−/− TBI mice towards an M2-like activation profile is in agreement with prior experimental studies that demonstrated a NOX2-dependent microglial switch from an M1-like to an M2-like activation state in response to LPS or Aβ1-42-mediated inflammatory challenge (Choi et al., 2012).

IL-4 induces M2-like activation (Colton, 2009; Gordon and Martinez, 2010); both IL-4 and the closely related cytokine IL-13 signal through IL-4Rα to stimulate potent anti-inflammatory functions (Sica and Mantovani, 2012). IL-4/IL-4Rα signaling is impaired with aging (Fenn et al., 2012; Nolan et al., 2005) and correlates with reduced functional recovery after SCI (Fenn et al., 2014). Moreover, there is an inverse relationship between increased microglial NOX2 expression and impaired IL-4 signaling in the aged TBI brain (Kumar et al., 2013). We show increased IL-4Rα expression in infiltrating macrophages after TBI in the absence of NOX2. When we blocked macrophage infiltration using a CCR2 antagonist IL-4Rα signaling and M2-like polarization levels in NOX2−/− TBI mice returned towards WT TBI levels, indicating that in the absence of NOX2, IL-4Rα+ infiltrating macrophages promote the M2-like phenotypic switch. IL-4 neutralization markedly suppresses M2-like activation in response to LPS challenge in NOX deficient (p47phox−/−) mice, and enhances M1-like responses (Choi et al., 2012). Furthermore, IL-4 deficiency alters M1-/M2-like balance in favor or M1-like activation and exacerbates neurological impairments after cerebral ischemia (Liu et al., 2016). In addition, loss of IL-4 significantly reduces the accumulation of CD206+ M2-like macrophages in the ischemic brain and decreases IL-10 expression (Liu et al., 2016). Thus, IL-4/IL-4Rα may play a critical role in initiating signal transduction that is required for M2-activation in NOX2−/− TBI mice.

To address potential clinical translation, we used the selective NOX2 peptide inhibitor, gp91ds-tat (Rey et al., 2001), administered systemically at 1, 2 and 3 days post-injury. gp91ds-tat is a peptide mimic that inhibits interactions between the cytosolic B-loop of NOX2 and p47phox, thereby preventing p47phox translocation to the membrane (Rey et al., 2001). It inhibits ROS production specifically by the NOX2 isoform, and has no effect on NOX1 or 4 (Csanyi et al., 2011). Delayed gp91ds-tat treatment significantly reduced NOX2 expression in activated microglia/macrophages at 7 days post-injury, up-regulated Arg1 and Ym1 expression in the hippocampus, and improved spatial working memory. gp91ds-tat treatment failed to improve motor function recovery after TBI, which may be related to the sub-acute time course of this study (improvements in motor function recovery in NOX2−/− TBI mice were only observed at 14 and 21 days post-injury), or other factors that will be evaluated in comprehensive follow-up neurological recovery studies that span the acute and chronic phase of recovery after TBI. Thus, reduced NOX2 activity and increased M2-like expression corresponded with superior cognitive performance in gp91ds-tat treated TBI mice. gp91ds-tat pre-treatment was shown to reduce cerebral edema and neurodegeneration in the ipsilateral hemisphere after TBI (Zhang et al., 2012), and delayed treatment significantly reduced oxidative stress-induced neuronal damage after TBI (Kumar et al., 2015). A major challenge in pre-clinical neuroprotection research is identifying targets for pharmacological intervention that have a long therapeutic window (Loane and Faden, 2010), as shown here for gp91ds-tat modulation of NOX2. Furthermore, for optimal neuroprotection that facilitates enhanced tissue repair both M1-like and M2-like functional responses will be required, including coordinated transitions between phenotypes that fine-tune sequential inflammatory, proliferative, resolution, and remodeling phases of repair (Novak and Koh, 2013), thereby harnessing the endogenous potential of microglia/macrophages to promote active repair and injury resolution following acute brain injury (Loane and Kumar, 2016).

In conclusion, we show that inhibiting NOX2 significantly reduces the neurotoxic M1-like phenotype, limits tissue loss and neurodegeneration, and improves long-term motor recovery after TBI; and that infiltrating NOX2+ inflammatory macrophages contribute to this pathology. Furthermore, loss of NOX2 promotes M2-like activation after TBI, likely through increased IL-4/IL-4Rα signaling in infiltrating macrophages. In addition, delayed systemic treatment with a peptide NOX2 inhibitor is neuroprotective, and improves cognitive function after TBI that is associated with increased M2-like markers in the hippocampus. Thus, therapeutic interventions that target NOX2 and skew microglia/macrophages towards beneficial M2-like activation may offer new antiinflammatory and neurorestorative treatment options for TBI.

Supplementary Material

Myeloid cells were isolated from the TBI cortex using a magnetic-bead-conjugated anti-CD11b antibody and MACS technology, and were stained with propidium iodide (PI), CD45-FITC and CD11b-APC prior to flow cytometry acquisition. Myeloid cells were identified using forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) profiles, which represent size and granularity, respectively, and viable cells were identified by PI staining (Gate R1) while dead cells (Gate R2) were excluded from the analysis. A CD45hi gate was used to distinguish infiltrating macrophages (CD11b+CD45hi) from resident microglia (CD11b+CD45lo) in sham and TBI samples. Using this flow cytometry protocol we routinely isolate 90–95% viable CD11b+CD45+ cells from sham and TBI cortex (data not shown).

Highlights.

NADPH oxidase (NOX2) is highly expressed in microglia and infiltrating inflammatory macrophages after TBI

NOX2 deficiency reduces M1-like neuroinflammation, limits tissue loss and neurodegeneration, and improves long-term neurological recovery after TBI

NOX2 inhibition promotes M2-like activation after TBI

NOX2 deficiency increases the infiltration of IL-4Rα+ macrophages after TBI

Delayed systemic treatment with a peptide NOX2 inhibitor is neuroprotective, and improves cognitive function after TBI by increasing M2-like expression in the hippocampus

Acknowledgments

We thank Ashley Singh for expert technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant R01NS082308 (D.J. Loane), R01NS037313 (A.I. Faden), The National Institute on Aging (NIA) Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center P30-AG028747 (D.J. Loane), and a CONACYT Scholarship 249772/389071 (DM Alvarez-Croda).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abais JM, Zhang C, Xia M, Liu Q, Gehr TW, Boini KM, Li PL. NADPH oxidase-mediated triggering of inflammasome activation in mouse podocytes and glomeruli during hyperhomocysteinemia. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;18:1537–1548. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aungst SL, Kabadi SV, Thompson SM, Stoica BA, Faden AI. Repeated mild traumatic brain injury causes chronic neuroinflammation, changes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity, and associated cognitive deficits. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34:1223–1232. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averaimo S, Milton RH, Duchen MR, Mazzanti M. Chloride intracellular channel 1 (CLIC1): Sensor and effector during oxidative stress. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2076–2084. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boche D, Perry VH, Nicoll JA. Review: activation patterns of microglia and their identification in the human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:3–18. doi: 10.1111/nan.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brune B, Dehne N, Grossmann N, Jung M, Namgaladze D, Schmid T, von Knethen A, Weigert A. Redox control of inflammation in macrophages. Antioxidants & redox signaling. 2013;19:595–637. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, Koeglsperger T, Dake B, Wu PM, Doykan CE, Fanek Z, Liu L, Chen Z, Rothstein JD, Ransohoff RM, Gygi SP, Antel JP, Weiner HL. Identification of a unique TGF-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes KR, Loane DJ, Stoica BA, Zhang J, Faden AI. Delayed mGluR5 activation limits neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012;9:43. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Kim GS, Okami N, Narasimhan P, Chan PH. NADPH oxidase is involved in postischemic brain inflammation. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;42:341–348. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Song YS, Chan PH. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase is neuroprotective after ischemiareperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:1262–1272. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry JD, Olschowka JA, O’Banion MK. Neuroinflammation and M2 microglia: the good, the bad, and the inflamed. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2014;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SH, Aid S, Kim HW, Jackson SH, Bosetti F. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase promotes alternative and anti-inflammatory microglial activation during neuroinflammation. Journal of neurochemistry. 2012;120:292–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]