Abstract

A comprehensive characterization of C-glycosyl flavones in wheat germ has been conducted using multi-stage high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMSn) in combination with a mass defect filtering (MDF) technique. MDF performed the initial search of raw data with defined C-glycosyl flavone mass windows and mass defect windows to generate the noise-reduced data focusing on targeted flavonoids. The high specificity of the exact mass measurement permits the unambiguous discrimination of acyl groups (nominal masses of 146, 162 and 176.) from sugar moieties (rhamnose, glucose or galactose and glucuronic acid). A total of 72 flavone C-glycosyl derivatives, including 2 mono-C-glycosides, 34 di-C-glycosides, 14 acyl di-C-glycosides and 7 acyl tri-C-glycosides, were characterized in wheat germ, some of which were considered to be important marker compounds for differentiation of whole grain and refined wheat products. The 7 acylated mono-O-glycosyl-di-C-glycosyl flavones and some acylated di-C-glycosyl flavones are reported in wheat for the first time. The frequent occurrence of numerous isomers is a remarkable feature of wheat germ flavones. Both UV and mass spectra are needed to maximize the structure information obtained for data interpretation.

Keywords: di-C-glycosyl flavones, O-acylated-C-glycosyl flavones, mass defect filter, wheat germ, high resolution mass spectrometry

Introduction

Wheat has been a basic staple food in Europe, West Asia, and North Africa for over 8,000 years. Today, wheat is grown on more land area than any other commercial crop and continues to be the most important food grain source for humans.[1] Whole grain wheat contains various health benefiting phytochemicals in addition to the basic and essential nutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, and dietary fiber). Among them, flavonoids, a large group of polyphenolic compounds, have gained attention due to their diverse health-promoting properties.[2, 3] Flavonoids normally accumulate in plants as O-glycosylated derivatives, but the major cereal crops, predominantly synthesize flavone C-glycosides. In wheat, the glycosidic forms are mainly apigenin and luteolin 6-C and/or 8-C-glycosidic conjugates.[4–7]

C-glycosyl flavonoids differ from O-glycosyl flavonoids in that their glycosyl moiety is attached via the anomeric carbon directly to the flavonoids backbone, almost exclusively at the C-6 or C-8 position of the A ring (Fig. 1A). In general, flavonoid C-glycosides are further divided into four classes: mono-C-glycosylflavonoids, di-C-glycosylflavonoids, O-glycosyl-C-glycosylflavonoids, (where O-glycosylation may be on the phenolic hydroxyl or on the sugar moiety from C-glycosylation, mainly at 2″ position followed by 6″ position), and O-acylated-C-glycosylflavonoids (in which different acyl groups are attached to the sugar moiety and/or to the flavonoid skeleton).[8, 9]

Figure 1.

Fragmentation nomenclature commonly used for flavonoid glycosides. A: 6-C-hexosyl-8-Cpentosyl-7-O-hexosyl apigenin; B: 6-C-(2″-O-hexosyl)-hexosyl flavonoid; C: 6-C-(6″-O-hexosyl)-hexosyl Flavonoid

Mass spectrometry has been extensively applied in the structure elucidation of flavonoid O-glycosides. The aglycone moiety, saccharide sequence, glycosylation position, and interglycosidic linkage position can be defined by a variety of MS methods.[10–14] Their cleavage occurs mainly at the glycosidic O-linkages, leading to the elimination of sugar moiety. Analysis of C-glycosyl flavonoids is more challenging than O-glycosyl flavonoids due to the following two facts: 1) internal cleavage in the sugar is favored over breakage of the carbon-carbon bond between the flavonoids and sugar moiety in the MS/MS fragmentation of protonated or deprotonated molecules for C-glycosyl flavonoids, and 2) the lack of standards, in particular for di-C-glycosides or more complex subtypes. Although MS/MS has been successfully used to characterize some di-C-glycosyl and O-C-diglycosyl flavonoids,[9, 15–18] complete structure elucidation by MS/MS is not routinely performed because authentic reference compounds with structural diversity are scarce and the relative intensities of characteristic fragments vary between instrument platforms and experimental conditions.

Profiling of flavonoid glycosides with LC-MS methods from wheat (Triticum aestivum) leaves[7] or grains[19, 20], and durum (Triticum durum) plant[4] or grains[21] was reported earlier. The wheat flavonoids are found to be mainly derivatives of only four flavones: apigenin, luteolin, chrysoeriol, and tricin. Tricin derivatives occur exclusively as O-glycosides, whereas apigenin and luteolin are always present as C-glycosides (Table 1). No special effort was dedicated to the study of C-glycosyl flavonoids of wheat germ. Our previous work has shown that apigenin 6-C-pentosyl-8-C-hexoside and its isomers from the germ fraction are the prominent discriminatory compounds to differentiate between whole grain and refined wheat flour.[22] Asenstorfer et al. also reported that apigenin C-diglycosides which are responsible for the yellow color of alkaline noodle are located only in the germ of wheat grains.[23] Hence, in the current study, closer attention was paid to wheat germ regarding its flavonoids constituents owing to their nutritional value and biological activities.

Table 1.

Aglycone structure of C-glycosyl flavones identified in wheat

| Name | Structure | Formula | MW | [M-H]− | Diagnostic ions of di-C-glycosides |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| apigenin |

|

C15H10O5 | 270.0528 | 269.0455 | 353(Ag+83), 383(Ag+113), 335(Ag+83−18), 365(Ag+113−18) |

| luteolin |

|

C15H10O6 | 286.0477 | 285.0405 | 369(Ag+83), 399(Ag+113), 351(Ag+83−18), 381(Ag+113−18) |

| chrysoeriol |

|

C16H12O6 | 300.0634 | 299.0561 | 383(Ag+83), 413(Ag+113), 365(Ag+83−18), 395(Ag+113−18) |

However, profiling flavonoids in foods is a very challenging and laborious task. Usually advanced expertise in both polyphenols and MS are required. To perform comprehensive profiling on a routine basis put tremendous demands on the knowledge and time on the analysts due to the sample complexity and the resulting large and complex datasets collected during HR-MS, HR-MS/MS, and MSn acquisitions. Using mass defect filtering (MDF) helps simplify the complex process by highlighting the candidate peaks of interest in raw data and save valuable time on data analysis.

The term “mass defect” originates from the fact that only the mono isotopic element 12C, has an integer value for atomic weight, i.e. 12.00000. Mass defect is defined as the difference between the exact mass of an element (or a compound) and its closest integer value. It may be positive (larger than the nominal mass) or negative (smaller than the nominal mass). Mass defect filtering (MDF) is a data filtering technique based on the mass defect of the core structure and its structural analogues that requires and takes advantage of HRMS. Initially, the MDF technique was developed for metabolite detection purposes based on a narrow and well-defined mass-defect window between the parent drug and its metabolites.[24] It is available as a post-acquisition data processing tool for various mass spectrometry vendor software packages, including MetWorks (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Similar to parent drug and its metabolites, a series of natural product analogs, like C-glycosyl flavones, share a common biosynthesis pathway and core-structure and differ in modification via oxidation, reduction, methylation, alkylation, rearrangement, etc. Therefore, they often possess similar mass defects.[6, 25] Based on this concept, MDF could be applied to detect natural constituents in a similar way as in drug metabolite screening. When a well-defined filter was applied to LC-HRMS data, the majority of interference ions were automatically removed, and the resulting simplified data made data analysis more straightforward. The following interpretation of candidate peaks relies on the understanding of nature and fragmentation behaviors of target compounds. The new strategy employing MDF was complementary to the traditional molecular mass/MS/MS fragmentation-based LC/MS approaches and greatly facilitated the identification process.

The present work applies the MDF as a screening technique for singling out potential C-glycosyl flavones of the four different types from wheat germ extract in a rapid manner. Then traditional molecular mass/MS/MS fragmentation-based LC/MS methodology is employed for mass spectral interpretation for structural information on the sugar classes and sizes and their substitution pattern on an aglycone. HRMS and MS/MS scan make it possible to differentiate caffeoyl (162.0317 Da) and p-coumaroyl (146.0368 Da) moieties from hexosyl (162.0528 Da) and deoxyhexosyl (146.0579 Da) residues. The recognition of acylated flavones glycosides with phenolic acids is achieved without performing alkaline hydrolysis to remove acyl residues.[26] To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on systematic MS characterization of various C-glycosylated flavonoids in wheat germ.

Experimental

Materials and chemicals

Raw wheat germ was purchased from local grocery stores. Standard samples of vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, isoorientin, and formic acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). HPLC grade methanol and acetonitrile were purchased from VWR International, Inc. (Clarksburg, MD, USA). HPLC water was prepared from distilled water using a Milli-Q system (Millipore Laboratories, Bedford, MA, USA).

Sample preparation

The germ flakes were ground into a fine powder and then passed through a 60 mesh sieve. A 500 mg sample of the germ powder was extracted with 20.0 mL of methanol-water (7:3, v/v) using a sonicator (Advanced Sonic Processing Systems, Oxford, CT, USA) at 16 kHz with 300W power for 40 min. The slurry mixture was centrifuged at 13000 g for 15 min in a Contifuge 28RS centrifuge (Heraeus, South Plainfield, NJ) at 4°C. The supernatant was evaporated to dryness on a rotary evaporator (Buchi RotaVapor, R-200, Buchi, Switzerland) at 50 °C. The dried sample was dissolved in 2 ml water and loaded onto a C18 SPE cartridge (500 mg, JT Baker, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). The loaded cartridge was washed with 5 mL of water, and the target compounds were eluted with 2 mL of methanol-water (4:6, v/v). The SPE elution was filtered through a 17 mm (0.20 μm) PVDF syringe filter (VWR Scientific, Seattle, WA) and stored at −80 °C until analysis.

The UPLC-HRMSn conditions

The UPLC-HRMSn system consists of a LTQ Orbitrap XL MS with an Acquity UPLC (Waters, Elstree, UK). The operating conditions of the ESI source are as follows: sheath gas at 80 (arbitrary units), auxiliary and sweep gas at 10 (arbitrary units), spray voltage at −4.0 kV; capillary temperature, 300 °C; capillary voltage, −50 V; tube lens offset, −150 V. The scan event cycle uses a FT full scan mass spectrum at a resolving power of 30,000 and three data-dependent MS2, MS3, MS4 events acquired by LTQ triggered by the most abundant ion from each previous scan event. The automated gain control (AGC) target value was set to 200,000 for FT full scan, and 10,000 for IT MSn scan. MSn activation parameters used an isolation width of 1.0 amu, max ion injection time of 200 ms, normalized collision energy at 25% (unless otherwise stated), and an activation time of 30 ms. To obtain accurate mass MS2 spectra, a dependent FT MS2 scan at a resolving power of 15,000 after an FT full scan was used when needed.

The UPLC separation was carried out on a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH 1.7 μm-C18 column (2.1 × 100 mm) with a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min. The mobile phase consist of a combination of A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). A gradient elution program was employed as follows: 10% B at 0–10.0 min, 15% B at 25.0–40.0min, 15% –25% B over 40.0 –50.0 min, 25% –50% B over 50.0 –55.0 min, 50% –90% B over 55.0 –60.0 min, and held at 90% B till 65.0 min. The column temperature was set at 40 °C. UV spectra were recorded between 200 and 500 nm.

Nomenclature

The fragmentation pattern of the sugar unit of C- and O- glycosyl flavones are present in Fig. 1. The cross-ring fragments of carbohydrates on flavonoid glycosides are denoted according to Domon and Costello.[27] The symbols k,lX−, Y−, and Z− represent the product ion still containing the intact aglycone, in which the superscripts k and l refer to the cleaved bonds within the carbohydrate rings. In some cases, a subscript, H, D or P, is added to labels referring to hexose, deoxyhexose, or pentose, respectively.

Results and discussion

MDF strategy to capture C-glycosyl flavones

Phytochemical investigations have shown that C-glycosides based on apigenin and luteolin are widespread in the genus Tricicum.[23, 28–32]. The MDF setting was defined using these published information. Glycosylation and acylation are the predominant modifications of wheat flavonoids. The sugars involved in the glycosylated flavonoids could be grouped into hexose (glucose and galactose), deoxyhexose (rhamnose), and pentose (arabinose and xylose). Triticum species contain O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavones acylated with a phenolic acid, i.e. ferulic acid, sinapic acid, p-coumaric acid, and caffeic acid.[9, 33] The mass value and mass defect of mono-, di-, tri-glycoside candidates, in free form or acylated, are predictable according to the core structure and possible substituents. Table 2 lists the mono-, di-, tri-, and feruloyl/sinapoyl di-glycoside candidates of apigenin and luteolin according to the literature cited previously. More predicted candidates are shown in supporting material Table S1.

Table 2.

Predicted glycoside candidates of apigenin and luteolin

| substituentsa | flavone glycoside candidates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Apigenin | Luteolin | ||||

|

|

|||||

| [M-H]− | mass defect (mDa) | [M-H]− | mass defect (mDa) | ||

| mono-glycoside | pen | 401.0875 | 86.7 | 417.0825 | 81.6 |

| dhex | 415.1031 | 102.3 | 431.0981 | 97.2 | |

| hex | 431.0980 | 97.2 | 447.0930 | 92.1 | |

| diglycoside | pen,pen | 533.1295 | 128.7 | 549.1245 | 123.6 |

| pen,dhex | 547.1451 | 144.3 | 563.1401 | 139.2 | |

| pen,hex | 563.1400 | 139.2 | 579.1350 | 134.1 | |

| dhex,hex | 577.1556 | 154.8 | 593.1506 | 149.7 | |

| hex,hex | 593.1505 | 149.7 | 609.1455 | 144.6 | |

| dhex,dhex | 561.1607 | 159.9 | 577.1557 | 154.8 | |

| triglycoside | pen,pen,pen | 665.1715 | 170.7 | 681.1665 | 165.6 |

| pen,pen,dhex | 679.1871 | 186.3 | 695.1821 | 181.2 | |

| pen,pen,hex | 695.1820 | 181.2 | 711.1770 | 176.1 | |

| dhex,dhex,dhex | 707.2183 | 217.5 | 723.2133 | 212.4 | |

| dhex,dhex,pen | 693.2027 | 201.9 | 709.1977 | 196.8 | |

| dhex,dhex,hex | 723.2132 | 212.4 | 739.2082 | 207.3 | |

| hex,hex,hex | 755.2030 | 202.2 | 771.1980 | 197.1 | |

| hex,hex,dhex | 739.2081 | 207.3 | 755.2031 | 202.2 | |

| hex,hex,pen | 725.1925 | 191.7 | 741.1875 | 186.6 | |

| pen,dhex,hex | 709.1976 | 196.8 | 725.1926 | 191.7 | |

| feruloyl-diglycoside | feruloyl,pen,pen | 709.1766 | 175.8 | 725.1716 | 170.7 |

| feruloyl,pen,dhex | 723.1922 | 191.4 | 739.1872 | 186.3 | |

| feruloyl,pen,hex | 739.1871 | 186.3 | 755.1821 | 181.2 | |

| feruloyl,dhex,hex | 753.2027 | 201.9 | 769.1977 | 196.8 | |

| feruloyl,hex,hex | 769.1976 | 196.8 | 785.1926 | 191.7 | |

| feruloyl,dhex,dhex | 737.2078 | 207.0 | 753.2028 | 201.9 | |

| sinapoyl-diglycoside | sinapoyl, pen,pen | 739.1871 | 186.3 | 755.1821 | 181.2 |

| sinapoyl, pen,dhex | 753.2027 | 201.9 | 769.1977 | 196.8 | |

| sinapoyl, pen,hex | 769.1976 | 196.8 | 785.1926 | 191.7 | |

| sinapoyl, dhex,hex | 783.2132 | 212.4 | 799.2082 | 207.3 | |

| sinapoyl, hex,hex | 799.2081 | 207.3 | 815.2031 | 202.2 | |

| sinapoyl, dhex,dhex | 767.2183 | 217.5 | 783.2133 | 212.4 | |

hex, hexosyl; pen, pentosyl; dhex, deoxyhexosyl.

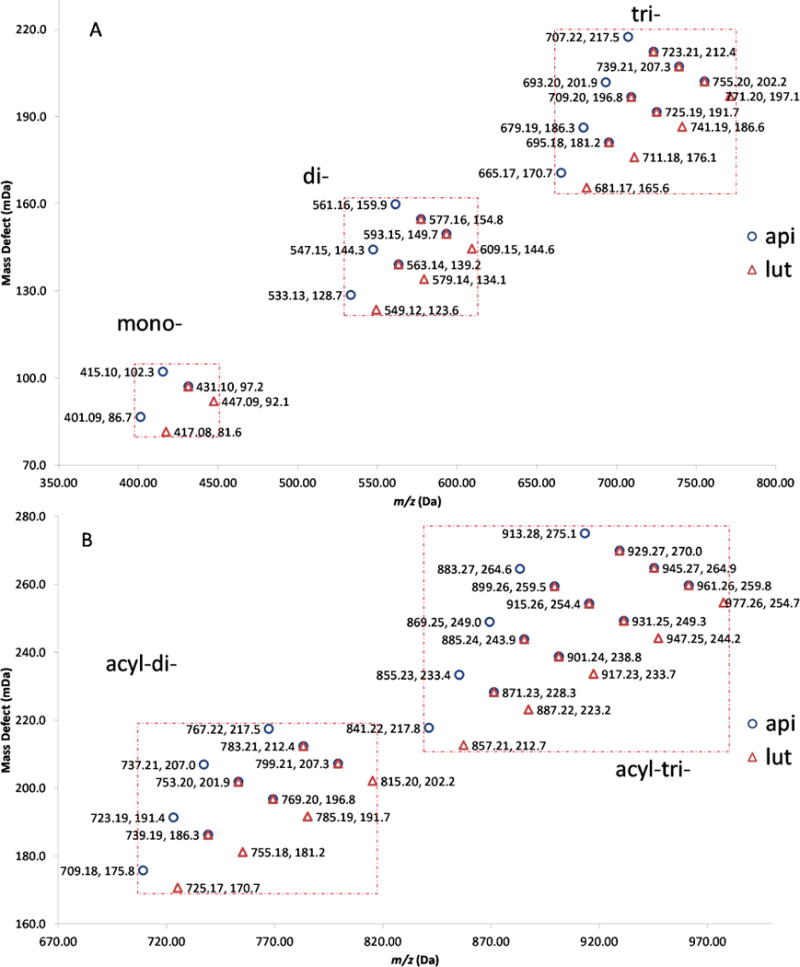

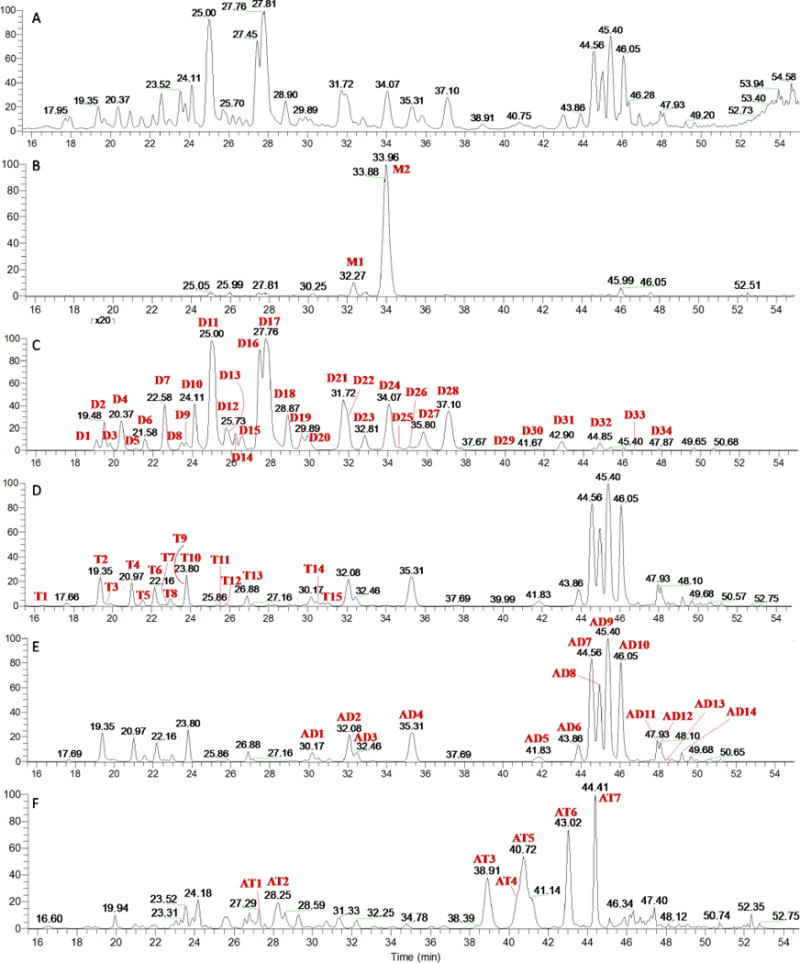

A good mass defect filter of C-glycosyl flavones depends strongly on defining two windows: the “mass defect window” (MDW) and the “C-glycosyl flavone mass window” (CFW), according to predicted substituents. An appropriate MDW will filter out those ions that fall into the CFW but out of the MDW, and vice versa. Five mass defect filters were constructed for screening C-glycosyl flavones in the crude extract of wheat germ with apigenin and luteolin as template compounds. Since these two aglycones are structurally similar (luteolin is 3′-OH apigenin), the mass defect profile calculated based on them are partly overlapped, as shown in Fig. 2. Each symbol represents a flavone glycoside candidate plotted against the accurate mass and mass defect values. The mass defect filters (shown in Fig 2 as dotted rectangles) with CFW/MDF setting slightly wider (± 0.1–0.2 Da/± 1.0–2.0 mDa) but covered all potential target compounds are: 1) 400.8–447.3 Da/80.0–104.0 mDa for flavone mono-glycosides; 2) 533.0–609.3 Da/122.0–161.5 mDa for di-glycosides; 3) 665.0–771.5 Da/164.0–219.0 mDa for tri-glycosides; 4) 709.0–815.5 Da/169.0–219.0 mDa for acyl-diglycosides, and 5) 841.0–977.5 Da/211.0–276.5 mDa for acyl-triglycosides. The unfiltered total ion chromatogram (TIC) and five filtered MS chromatograms are compared in Fig. 3, wherein different peaks were picked out from the TIC by each filter. It is easy to see that the MDF allows the analyst to quickly zero in on the respective groups of compounds, thus, greatly facilitating the identification process. The peak profiles in Fig. 3D and 3E are very similar, it is reasonable because the filter settings for tri-glycosides and acyl-diglycosides mostly overlap, as seen in Fig. 2. The structural characterization of the candidates relies on retention times, UV spectra, MS spectra (HRMS, HR-MS/MS, MS3, MS4), and the use of standards when available (stacked chromatograms of the UV traces and BPC are shown in Fig. S1). A total of 72 C-glycosyl flavones, including 2 mono-, 34 di-, 15 tri-, 14 acyl di-, and 7 acyl tri-glycosides, were characterized (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Mass defect profiles of predicted flavone glycoside candidates. Symbols: ○ apigenin as template, △ luteolin as template. A: non-acylated mono-, di-, and tri-glycosides; B: acylated di- and tri-glycosides.

Figure 3.

The unfiltered TIC of raw data (A) and filtered chromatograms obtained by different CFW/MDW setting as follows: (B) 400.8–447.3 Da/80.0–104.0 mDa for mono-glycosides; (C) 533.0–609.3 Da/122.0–161.5 mDa for diglycosides; (D) 665.0–771.5 Da/164.0–219.0 mDa for triglycosides; (E) 709.0–815.5 Da/169.0–219.0 mDa for acyl-diglycosides; and (F) 841.0–977.5 Da/211.0–276.5 mDa for acyl-triglycosides.

Table 3.

The C-glycosyl flavones characterized in wheat germ

| Peak No. | ion m/z | RT | error (ppm) | RDB | Formula [M-H]− | MSn data | partial identificationa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | 431.0985 | 32.27 | 0.302 | 12.5 | C21H19O10 | MS2[431.1]: 341.1(7), 311.1(100); MS3[431.1–>311.1]: 283.1(100), 268.0(2), 191.0(2) | vitexin |

| M2 | 431.0985 | 33.96 | 0.302 | 12.5 | C21H19O10 | MS2[431.1]: 413.1(6), 341.1(29), 311.1(100); MS3[431.1–>311.1]: 283.1(100) | isovitexin |

| D1 | 609.1451 | 19.09 | −1.655 | 13.5 | C27H29O16 | MS2[609.2]: 591.4(6), 519.3(27), 489.1(100), 471.4(8), 399.2(15), 369.4(12) | luteolin 6,8-di-C-hex |

| D2 | 579.1356 | 19.48 | 0.098 | 13.5 | C26H27O15 | MS2[579.1]: 561.2(8), 519.3(39), 489.2(100); MS3[579.1–>489.2]: 471.2(11), 399.2(41), 369.1(100) | luteolin 6-C-pen-8-C-hex |

| D3 | 593.1512 | 19.79 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(8), 503.3(40), 473.2(100), 383.1(15), 353.2(28) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-hex |

| D4 | 593.1512 | 20.37 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(9), 503.3(44), 473.3(100), 383.2(25), 353.2(27); MS3[593.2–>473.2]: 383.1(28), 353.2(100) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-hex |

| D5 | 579.1356 | 21.13 | 0.098 | 13.5 | C26H27O15 | MS2[579.1]: 561.1(14), 519.2(13), 489.3(50), 459.1(100), 441.2(8), 399.2(16), 369.1(11) | luteolin 6-C-hex-8-C-pen |

| D6 | 563.1406 | 21.58 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(27), 503.1(78), 473.1(90), 443.2(100), 425.2(15), 413.2(11), 383.3(56), 353.2(40); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 425.3(18), 383.1(62), 353.1(100); MS3[563.1–>473.1]: 383.3(26), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D7 | 593.1512 | 22.58 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(12), 503.2(33), 473.2(100), 383.2(19), 353.3(28); MS3[593.2–>473.2]: 383.2(20), 353.2(100); MS3[593.2–>503.2]: 413.3(18), 383.2(100) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-hex |

| D8 | 563.1406 | 23.47 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.3(15), 503.2(12), 473.2(100), 443.2(80), 383.2(32), 353.2(54); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(11), 383.2(83), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 383.2(18), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D9 | 579.1356 | 23.69 | 0.098 | 13.5 | C26H27O15 | MS2[579.1]: 489.2(25), 459.2(100), 399.2(9); MS3[579.1–>459.2]: 441.3(33), 399.1(95), 369.2(100) | luteolin 6-C-hex-8-C-pen |

| D10 | 579.1356 | 24.11 | 0.098 | 13.5 | C26H27O15 | MS2[579.1]: 561.2(14), 519.2(15), 489.2(100), 459.3(17), 399.3(17), 369.3(12); MS3[579.1–>489.2]: 471.2(10), 429.1(8), 399.2(67), 369.2(100); MS3[579.1–>459.3]: 399.2(21), 369.2(100) | luteolin 6-C-pen-8-C-hex |

| D11 | 563.1406 | 25.00 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.4(27), 503.2(41), 473.2(100), 443.3(98), 425.2(9), 383.3(34), 353.3(33); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(22), 383.2(88), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>443.3]: 383.1(34), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D12 | 563.1406 | 25.73 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(19), 503.2(29), 473.2(100), 455.2(12), 443.2(62), 383.2(30), 353.2(34); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(8), 383.1(62), 353.1(100); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 425.2(8), 383.3(29), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D13 | 579.1356 | 25.88 | 0.098 | 13.5 | C26H27O15 | MS2[579.1]: 561.2(13), 519.1(16), 489.2(100), 459.3(14), 399.2(16), 369.2(14); MS3[579.1–>489.2]: 471.2(11), 399.1(68), 369.1(100) | luteolin 6-C-pen-8-C-hex |

| D14 | 563.1406 | 26.20 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.3(11), 503.2(17), 473.2(100), 455.3(14), 443.2(56), 413.2(9), 383.2(32), 353.1(33); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 455.2(8), 413.2(18), 383.2(100), 353.2(86); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 383.2(23), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D15 | 563.1406 | 26.54 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.3(32), 503.1(67), 485.3(9), 473.2(88), 443.2(100), 425.3(17), 413.2(11), 383.2(55), 353.2(42); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 425.2(17), 383.3(65), 353.1(100); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.3(11), 383.3(28), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D16 | 563.1406 | 27.45 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(13), 503.2(8), 473.2(60), 443.2(100), 383.3(19), 353.2(26); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 383.2(24), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(22), 383.2(100), 353.1(36) | apigenin 6-C-hex-8 C-pen |

| D17 | 563.1406 | 27.76 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(34), 503.3(81), 473.2(100), 443.2(88), 425.2(15), 383.2(50), 353.2(40); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 383.1(23), 353.1(100); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 425.1(21), 383.2(63), 353.2(100) | apigenin 6-C-pen-8 C-hex |

| D18 | 563.1406 | 28.87 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.3(12), 503.2(11), 473.2(88), 455.2(12), 443.3(100), 383.2(20), 353.2(31); MS3[563.1–>443.3]: 383.2(15), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.1(14), 383.1(100), 353.2(49) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D19 | 593.1512 | 29.60 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(12), 533.2(29), 503.3(46), 473.3(100), 413.2(32), 383.2(33); MS3[593.2–>473.3]: 455.1(20), 413.2(59), 383.2(100); MS3[593.2–>503.3]: 413.4(15), 383.3(100) | chrysoeriol C-hex, C-pen |

| D20 | 563.1406 | 29.89 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(17), 503.3(19), 473.2(100), 455.2(18), 443.2(65), 383.2(34), 353.2(40); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.1(15), 383.1(78), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 383.2(24), 353.1(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D21 | 563.1406 | 31.72 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(11), 473.2(53), 443.2(100), 383.2(11), 353.2(21); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 383.2(14), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(13), 383.2(100), 353.2(24) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D22 | 593.1512 | 31.93 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.3(12), 503.2(85), 473.2(100), 413.2(20), 383.2(41); MS3[593.2–>473.2]: 413.2(11), 383.2(100); MS3[593.2–>503.2]: 443.3(11), 413.2(100), 383.1(70) | chrysoeriol C-hex, C-pen |

| D23 | 563.1406 | 32.81 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.2(16), 503.2(23), 473.2(47), 443.2(100), 425.2(18), 383.2(39), 353.2(43); MS3[563.1–>443.2]: 425.2(15), 383.2(47), 353.2(100); MS3[563.1–>473.2]: 413.2(20), 383.2(46), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D24 | 533.1300 | 34.07 | −0.120 | 13.5 | C25H25O13 | MS2[533.1]: 515.3(21), 473.2(55), 443.2(100), 383.3(15), 353.3(15); MS3[533.1–>443.2]: 383.1(28), 353.2(100); MS3[533.1–>473.2]: 413.2(26), 383.2(100) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-pen |

| D25 | 593.1512 | 34.57 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(9), 533.3(9), 503.2(100), 485.2(11), 473.3(51), 413.2(18), 383.1(34) | chrysoeriol C-hex, C-pen |

| D26 | 577.1563 | 35.08 | 0.037 | 13.5 | C27H29O14 | MS2[577.2]: 559.3(32), 503.1(49), 487.3(17), 473.2(73), 457.3(100), 439.3(11), 383.2(38), 353.2(40) | apigenin C-hex, C-dhex |

| D27 | 593.1512 | 35.80 | 0.011 | 13.5 | C27H29O15 | MS2[593.2]: 575.2(15), 533.2(8), 503.2(99), 473.2(100), 413.2(22), 383.2(49); MS3[593.2–>473.2]: 413.2(7), 383.2(100); MS3[593.2–>503.2]: 485.3(7), 443.2(8), 413.2(100), 383.1(79) | chrysoeriol C-hex, C-pen |

| D28 | 533.1300 | 37.10 | −0.120 | 13.5 | C25H25O13 | MS2[533.1]: 515.2(21), 473.2(64), 455.2(8), 443.2(100), 425.3(6), 383.3(20), 353.3(16); MS3[533.1–>443.2]: 383.2(31), 353.1(100); MS3[533.1–>473.2]: 413.2(28), 383.2(100) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-pen |

| D29 | 533.1300 | 40.26 | −0.120 | 13.5 | C25H25O13 | MS2[533.1]: 515.3(19), 473.2(59), 455.2(6), 443.3(100), 383.2(8), 353.3(13) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-pen |

| D30 | 563.1406 | 41.67 | −0.051 | 13.5 | C26H27O14 | MS2[563.1]: 545.3(16), 503.2(49), 485.3(3), 473.2(100), 455.3(4), 443.3(6), 413.2(14), 383.2(22), 353.4(3) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen |

| D31 | 577.1563 | 42.90 | 0.037 | 13.5 | C27H29O14 | MS2[577.2]: 559.3(19), 503.2(51), 487.3(19), 473.2(50), 457.2(100), 439.2(9), 413.2(8), 383.3(39), 353.2(33); MS3[577.2–>457.2]: 439.2(11), 383.1(53), 353.2(100); MS3[577.2–>503.2]: 413.2(14), 383.2(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-dhex |

| D32 | 533.1300 | 44.85 | −0.120 | 13.5 | C25H25O13 | MS2[533.1]: 515.2(21), 473.2(61), 443.2(100), 383.2(11), 353.2(14); MS3[533.1–>443.2]: 383.3(18), 353.1(100); MS3[533.1–>473.2]: 413.2(16), 383.2(100) | apigenin 6,8-di-C-pen |

| D33 | 547.1455 | 46.62 | −0.391 | 13.5 | C26H27O13 | MS2[547.2]: 529.2(23), 473.3(48), 457.2(23), 443.2(100), 383.2(25), 353.2(26) | apigenin C-dhex, C-pen |

| D34 | 547.1455 | 47.87 | −0.391 | 13.5 | C26H27O13 | MS2[547.2]: 529.4(16), 473.2(78), 457.2(37), 443.3(100), 413.3(11), 383.1(37), 353.3(29) | apigenin C-dhex, C-pen |

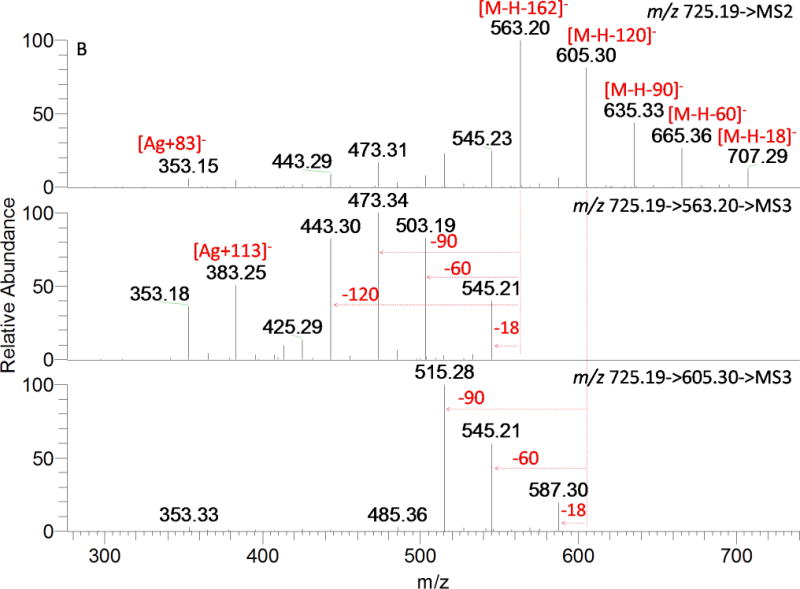

| T1 | 725.1935 | 16.49 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(19), 665.4(11), 635.4(100), 605.3(76), 563.3(79), 545.3(17), 515.4(12), 503.3(15), 473.3(52), 443.2(44), 383.3(20), 353.3(23) | apigenin O-hex, C-hex, C-pen |

| T2 | 725.1935 | 19.35 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 635.3(23), 527.2(22), 473.2(80), 443.3(100), 383.2(32), 353.2(35); MS3[725.2–>443.3]: 383.2(26), 353.2(100); MS3[725.2–>473.2]: 413.2(24), 383.1(100) | apigenin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| T3 | 741.1878 | 19.67 | −0.764 | 14.5 | C32H37O20 | MS2[741.2]: 723.3(15), 681.3(21), 651.2(100), 543.3(17), 489.2(29), 459.2(40), 453.2(16), 399.3(40), 369.2(43) | luteolin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| T4 | 725.1935 | 20.97 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(21), 665.2(31), 635.3(40), 473.2(25), 443.2(100), 383.2(46), 353.2(46); MS3[725.2–>443.2]: 425.2(17), 383.1(49), 353.1(100) | apigenin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| T5 | 725.1935 | 21.55 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(13), 665.4(26), 635.3(43), 605.3(81), 563.2(100), 545.2(24), 515.2(23), 473.3(17); MS3[725.2–>563.2]: 545.2(40), 503.2(82), 473.3(100), 443.3(82), 425.3(13), 383.3(50), 353.2(36); MS3[725.2–>605.3]: 587.3(19), 545.2(60), 515.3(100) | apigenin O-hex, C-hex, C-pen |

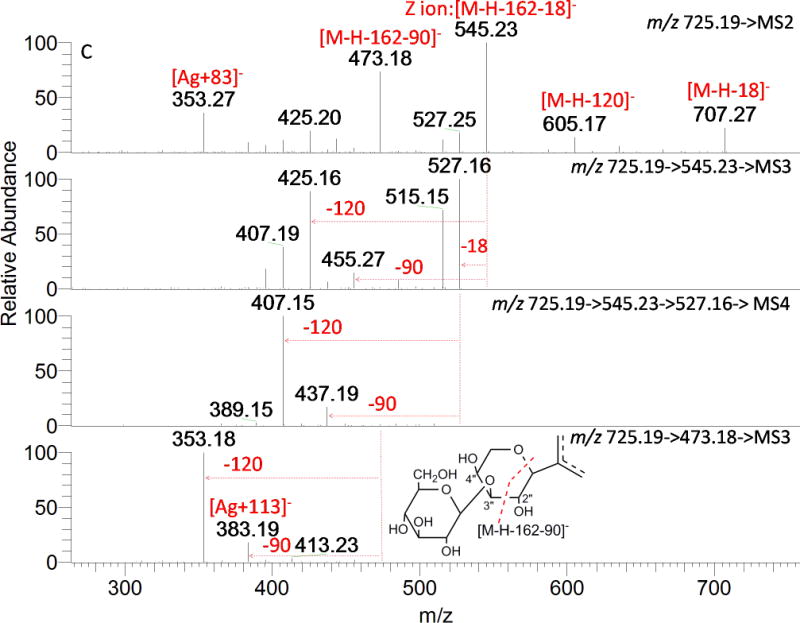

| T6 | 725.1935 | 22.16 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(20), 605.3(15), 545.2(100), 527.3(15), 473.3(72), 425.2(19), 353.2(30); MS3[725.2–>545.2]: 527.2(100), 515.3(65), 455.3(14), 425.2(91), 407.2(36), 395.3(16); MS3[725.2–>473.3]: 383.2(18), 353.2(100); MS4[725.2–>545.2–>527.2]: 437.2(17), 407.1(100) | apigenin C-(2″-O-hex)pen, C-hex |

| T7 | 755.2040 | 22.74 | −0.022 | 14.5 | C33H39O20 | MS2[755.2]: 737.3(9), 695.2(6), 665.4(19), 635.4(4), 575.3(8), 557.3(10), 515.3(5), 503.2(26), 473.2(100), 455.2(8), 443.3(4), 413.3(24), 395.3(6), 383.2(37), 353.2(8) | apigenin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-hex |

| T8 | 725.1935 | 22.95 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 635.3(16), 527.2(22), 473.2(48), 443.1(100), 383.2(21), 353.2(36); MS3[725.2–>443.1]: 383.2(23), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| T9 | 741.1878 | 23.69 | −0.764 | 14.5 | C32H37O20 | MS2[741.2]: 723.3(12), 681.4(12), 651.3(100), 561.3(50), 501.3(15), 471.3(23), 459.1(26), 369.2(27) | luteolin 6-C-pen, 8-C-(2″-O-hex)hex |

| T10 | 725.1935 | 23.80 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.4(12), 665.3(23), 635.3(27), 527.2(6), 473.2(24), 443.2(100), 425.4(10), 413.2(8), 383.2(44), 353.2(40); MS3[725.2–>443.2]: 425.2(19), 383.1(64), 353.2(100) | apigenin C-(6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| T11 | 725.1935 | 25.49 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.4(22), 665.4(76), 635.3(100), 605.4(43), 575.2(10), 545.3(61), 527.2(16), 473.3(41), 407.1(10), 383.2(11), 353.2(21) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen, O-hex |

| T12 | 725.1935 | 25.86 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(37), 665.3(37), 647.3(4), 635.4(100), 617.3(8), 575.3(12), 545.3(40), 527.1(5), 485.4(6), 455.3(20), 395.3(3), 365.2(7) | chrysoeriol C-pen, C-(O-hex) pen |

| T13 | 725.1935 | 26.88 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(11), 635.3(8), 545.2(50), 527.2(21), 485.2(37), 443.2(100), 395.3(7), 383.2(7), 353.1(31); MS3[725.2–>545.2]: 527.3(58), 485.2(100), 455.1(15), 395.2(4), 365.3(5); MS3[725.2–>443.2]: 383.1(24), 353.1(100) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen, O-hex |

| T14 | 725.1935 | 30.47 | 0.066 | 14.5 | C32H37O19 | MS2[725.2]: 707.3(9), 635.4(8), 545.3(38), 527.3(21), 485.3(36), 443.2(100), 383.3(9), 353.2(28) | apigenin C-hex, C-pen, O-hex |

| T15 | 755.2040 | 31.06 | −0.022 | 14.5 | C33H39O20 | MS2[755.2]: 737.3(12), 677.3(4), 665.3(19), 575.2(45), 557.3(20), 515.2(30), 485.3(7), 473.2(100), 425.2(13), 383.2(36), 353.2(1) | apigenin C-(3″-O-hex)hex, C-hex |

| AD1 | 743.1829 | 30.17 | 0.017 | 18.5 | C35H35O18 | MS2[743.2]: 725.2(2), 545.1(100), 425.1(5); MS3[743.2–>545.1]: 425.2(100); MS3[743.2–>425.1]: 425.2(11), 365.2(41), 335.2(100), 305.1(20) | apigenin 2″-O-syringoyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD2 | 713.1722 | 32.1 | −0.172 | 18.5 | C34H33O17 | MS2[713.2]: 545.1(100), 425.1(6); MS3[713.2–>545.1]: 455.2(3), 425.2(100); MS3[713.2–>425.1]: 365.2(33), 335.2(100), 305.2(17) | apigenin 2″-O-vanilloyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD3 | 743.1829 | 32.46 | 0.017 | 18.5 | C35H35O18 | MS2[743.2]: 545.1(100), 425.1(5); MS3[743.2–>545.1]: 455.3(4), 425.1(100); MS3[743.2–>425.1]: 365.1(47), 335.1(100) | apigenin 2″-O-syringoyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD4 | 713.1722 | 35.31 | −0.172 | 18.5 | C34H33O17 | MS2[713.2]: 545.1(100), 425.2(4); MS3[713.2–>545.1]: 455.2(3), 425.2(100); MS3[713.2–>425.2]: 365.2(59), 335.2(100), 305.1(15) | apigenin 2″-O-vanilloyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD5 | 709.1775 | 41.83 | 0.130 | 19.5 | C35H33O16 | MS2[709.2]: 563.1(5), 545.1(100), 425.1(5); MS3[709.2–>545.1]: 455.2(4), 425.2(100); MS3[709.2–>425.1]: 365.2(10), 335.2(100), 305.2(17) | apigenin 2″-O-p-coumaroyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD6 | 709.1775 | 43.86 | 0.130 | 19.5 | C35H33O16 | MS2[709.2]: 563.1(6), 545.1(100), 425.1(5); MS3[709.2–>563.1]: 545.3(33), 503.2(100), 473.2(88), 443.3(90), 425.3(15), 383.3(53), 353.3(39); MS3[709.2–>545.1]: 455.3(4), 425.2(100) | apigenin 2″-O-p-coumaroyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD7 | 769.1986 | 44.56 | 0.082 | 19.5 | C37H37O18 | MS2[769.2]: 563.2(3), 545.2(100), 425.3(11); MS3[769.2–>545.2]: 455.2(2), 425.2(100); MS3[769.2–>425.3]: 365.1(33), 335.1(100), 305.2(17) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD8 | 739.1879 | 44.98 | −0.098 | 19.5 | C36H35O17 | MS2[739.2]: 563.2(2), 545.2(100), 425.3(9); MS3[739.2–>545.2]: 455.1(3), 425.2(100); MS3[739.2–>425.3]: 365.2(31), 335.2(100), 305.2(17) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD9 | 769.1986 | 45.40 | 0.082 | 19.5 | C37H37O18 | MS2[769.2]: 563.4(3), 545.3(100), 425.2(10); MS3[769.2–>545.3]: 455.2(4), 425.2(100); MS3[769.2–>425.2]: 365.1(50), 335.1(100) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD10 | 739.1879 | 46.05 | −0.098 | 19.5 | C36H35O17 | MS2[739.2]: 563.3(3), 545.2(100), 425.2(7); MS3[739.2–>545.2]: 455.2(3), 425.2(100); MS3[739.2–>425.2]: 365.2(50), 335.2(100), 305.2(15) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-hex, C-pen |

| AD11 | 739.1879 | 47.93 | −0.098 | 19.5 | C36H35O17 | MS2[739.2]: 545.2(6), 515.3(100); MS3[739.2–>515.3]: 425.1(100); MS4[739.2–>515.3–>425.1]: 365.2(57), 335.1(100), 305.1(7) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-pen, C-pen |

| AD12 | 709.1775 | 48.10 | 0.130 | 19.5 | C35H33O16 | MS2[709.2]: 533.3(2), 515.2(100), 425.2(4); MS3[709.2–>515.2]: 425.1(100); MS4[709.2–>515.2–>425.1]: 407.2(6), 365.1(53), 335.2(100), 307.2(11), 305.2(10), 241.2(10) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-pen, C-pen |

| AD13 | 709.1775 | 48.48 | 0.130 | 19.5 | C35H33O16 | MS2[709.2]: 533.3(2), 515.2(100), 425.2(3); MS3[709.2–>515.2]: 425.2(100); MS4[709.2–>515.2–>425.2]: 365.1(50), 335.2(100), 305.1(8) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-pen, C-pen |

| AD14 | 769.1986 | 49.20 | 0.082 | 19.5 | C37H37O18 | MS2[769.2]: 563.1(3), 545.1(100), 425.1(6); MS3[769.2–>545.1]: 455.1(3), 425.3(100); MS3[769.2–>425.1]: 365.3(41), 335.3(100), 305.1(35) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-hex, C-pen |

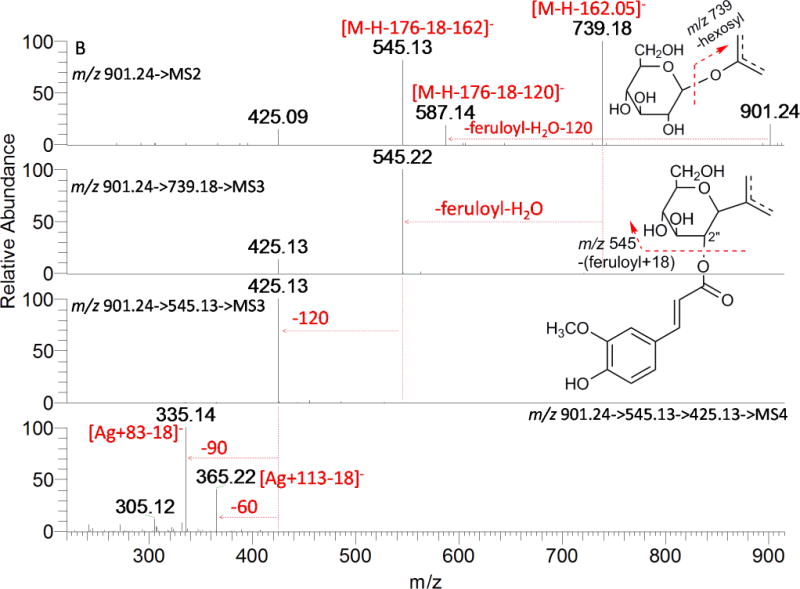

| AT1 | 901.2408 | 27.3 | 0.004 | 20.5 | C42H45O22 | MS2[901.2]: 739.2(100), 587.1(19), 545.1(92), 425.1(16); MS3[901.2–>739.2]: 545.2(100), 425.2(9); MS3[901.2–>545.1]: 455.2(3), 425.2(100); MS4[901.2–>545.2–>425.2]: 365.2(41), 335.1(100), 305.1(12) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, O-hex, C-hex, C-pen |

| AT2 | 931.2515 | 28.25 | 0.150 | 20.5 | C43H47O23 | MS2[931.2]: 769.1(39), 587.4(1), 545.1(100), 455.0(2), 425.2(28), 365.1(1), 335.3(2) | apigenin O-sinapoyl, O-hex, C-hex, C-pen |

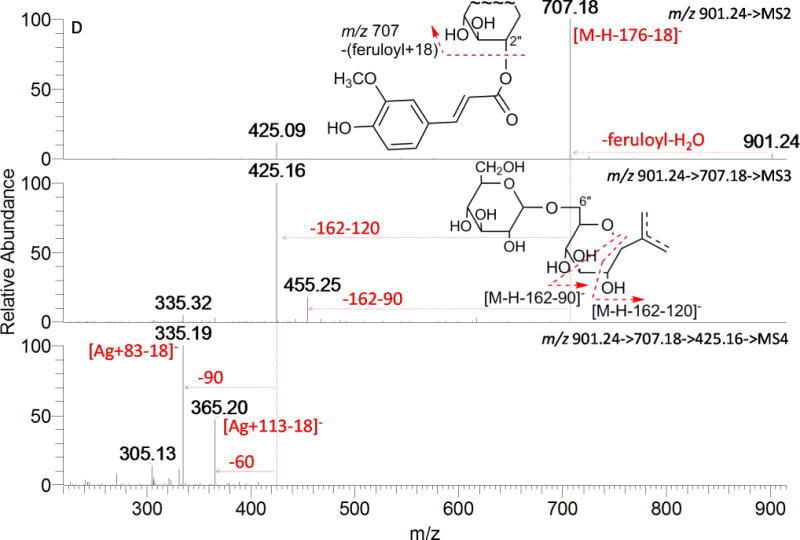

| AT3 | 931.2515 | 38.9 | 0.150 | 20.5 | C43H47O23 | MS2[931.2]: 725.3(2), 707.3(100), 425.3(14); MS3[931.2–>707.3]: 617.4(4), 455.2(15), 443.3(2), 425.2(100), 365.3(2), 335.1(3) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl,C-(4″ or 6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| AT4 | 931.2515 | 40.4 | 0.150 | 20.5 | C43H47O23 | MS2[931.2]: 725.4(5), 707.3(100), 587.4(22); MS3[931.2–>707.3]: 617.1(2), 587.3(100), 335.2(2); MS4[931.2–>707.3–>587.2]: 425.3(100), 407.2(8), 335.2(31) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-(3″ or 4″-O-hex)pen, C-hex |

| AT5 | 901.2408 | 40.7 | 0.004 | 20.5 | C42H45O22 | MS2[901.2]: 707.2(100), 425.2(11); MS3[901.2–>707.2]: 587.3(43), 455.2(17), 425.1(100); MS4[901.2–>707.2–>425.1]: 365.2(36), 335.1(100), 305.3(16) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-hex-O-hex, C-pen |

| AT6 | 931.2515 | 43 | 0.150 | 20.5 | C43H47O23 | MS2[931.2]: 725.4(2), 707.3(100), 425.2(15); MS3[931.2–>707.3]: 617.4(3), 527.2(2), 455.2(16), 443.3(2), 425.2(100), 365.2(2), 335.2(4); MS4[931.2–>707.2–>425.2]: 365.2(45), 335.3(100) | apigenin 2″-O-sinapoyl,C-(4″ or 6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

| AT7 | 901.2408 | 44.4 | 0.004 | 20.5 | C42H45O22 | MS2[901.2]: 707.3(100), 425.3(15); MS3[901.2–>707.3]: 455.1(18), 425.1(100); MS4[901.2–>707.3–>425.1]: 365.2(47), 335.2(100), 331.1(14), 305.1(13) | apigenin 2″-O-feruloyl, C-(4″ or 6″-O-hex)hex, C-pen |

hex: hexosyl; pen: pentosyl; dhex: deoxyhexosyl

Mono-C- and di-C-glycosyl flavones

In contrast to O-glycosides, which can be easily characterized by the loss of sugar moiety, the fragmentations of C-glycosides occur preferentially on the glycosidic moiety. The product ions are usually aglycones with sugar moieties that remain linked. Thus, the ions [Ag+41]−/[Ag+71]− in mono-C and [Ag+83]−/[Ag+113]− in di-C are indicative of the nature of the aglycones (Table 1).[9, 16] Since the vast majority of C-linked sugars have been found at C-6- and/or C-8- positions,[8] the major challenge here is the differentiation between 6-C- and 8-C-glycosyl flavones and the determination of the type of sugar substituted at the C-6 and C-8 positions in 6,8-di-C-glycosyl flavones.

Four authentic mono C-glucosides (vitexin, isovitexin, orientin, and isoorientin) were compared by collision induced dissociation (CID) analysis in the LTQ Orbitrap platform described in the instrument section. The CID behaviors of the two groups of isomers at varying collision energy are shown in Fig. 4. The fragmentation characteristics are similar to those reported by other researchers.[10, 16, 26, 34, 35] Loss of water in the deprotonated ion [M-H]− are much more pronounced for 6-C- than 8-C-glycosyl flavonoids.[16, 36] 6-C-isomers can easily lose water between the 2″-hydroxyl group of the sugar and the 5- or 7-hydroxyl groups of the aglycone, which is facilitated by hydrogen bonding between either the oxygen atom of the sugar ring and the 5- or 7-hydroxyl group of the aglycone part; whereas 8-C-glycosyl flavonoids lose water only with the 7-hydroxyl group, a process that is counteracted by hydrogen bonding between either the oxygen atom of the sugar and the 7-hydroxyl group of the aglycone.[10, 37] The other distinctive difference between 6-C- and 8-C-isomers lies in the relative intensities of ion 0,3X, which are higher in 6-C-isomers in comparison to 8-C-isomers (Fig. 4B vs. 4A; 4D vs. 4C). Collision energy at 25% selected in this study achieved reliable and distinguishable spectra.

Figure 4.

High resolution MS/MS spectra of vitexin (A: apigenin 8-C-glucoside), isovitexin (B: apigenin 6-Cglucoside), orientin (C: luteolin 8-C-glucoside) and isoorientin (D: luteolin 6-C-glucoside) at different collision energies.

Peaks M1 and M2 (Fig. 3B) were identified as vitexin (apigenin 8-C-glucoside) and isovitexin (apigenin 6-C-glucoside), respectively, by chromatographic and mass spectral analysis with reference standards. Vitexin elutes ahead of isovitexin on our reverse phase LC system. The result is in agreement with previous reports that C-8-glycoside elutes before its C-6 isomer.[38–40]

In di-C-glycosides, preferential fragmentation of the sugar moiety is at the C-6 rather than the C-8 position. However, it is difficult to establish the position of C-glycosylation if there is no co-existence of both isomers. Wheat flavonoids are featured with multiple isomers, as shown in Table 3 and other reports.[19, 23] It is not possible to determine whether these two compounds are a pair of Wessely-Moser isomers or have isomeric sugars by MS alone. The factors that influence the relative intensities of cross-ring cleavage fragments (including [M-H-120]−, [M-H-90]−, and [M-H-60]−) are complicated. Cao et al. found that the relative intensities of these structure-diagnostic ions are highly dependent on the nature and anomeric configuration of the sugars at C-6 and C-8.[18] Based on the above considerations, the precise placement of pentose, hexose, and deoxyhexose, at the C-6 or C-8 was not determined in this study.

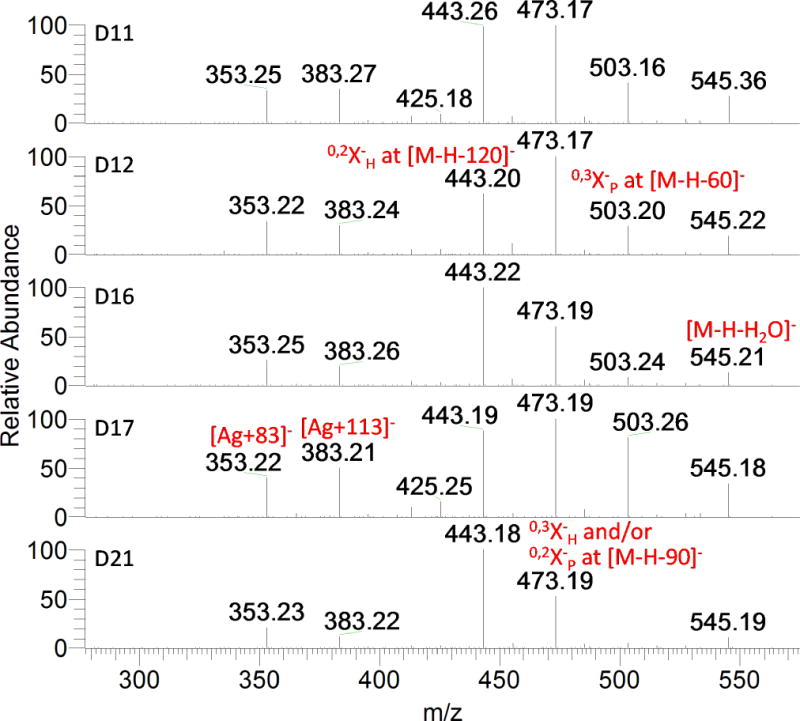

Compounds D6, D8, D11, D12, D14, D15, D16, D17, D18, D20, D21, D23, and D30 present the same deprotonated molecule ion at m/z 563.1406 (C26H27O14). They share some major product ions in the MS2 spectra as shown in Fig. 5. They all produce the fragment ions at m/z 353 (Ag+83) and 383 (Ag+113), which are characteristic of the di-C-glycosylflavone fragmentation, suggesting the trihydroxylated nature of the aglycone (Table 1, apigenin, MW 270). The UV spectra of these peaks presented λmax at 270–272 and 335–337 nm, providing additional evidence of di-C-glycosyl apigenin.[39, 41, 42] The ion at m/z 473 [M−H−90]− could be produced by 0,2X cleavage of a pentose or 0,3X cleavage of a hexose. The [M−H−60]− ion at m/z 503 and the [M−H−120]− ion at m/z 443 can only be produced by cleavage of the 0,3 bond of C-pentosyl (0,3XP) and the 0,2 bond of C-hexosyl (0,2XH), respectively. (Fig. 1). The ion at m/z 545 was produced by losing one molecule of H2O. Therefore the compounds are concluded to be isomers of 6,8-di-C-hexosyl/pentosyl apigenin.

Figure 5.

MS/MS spectra of the ions at m/z 563.14 corresponding to compounds D11, D12, D16, D17, and D21.

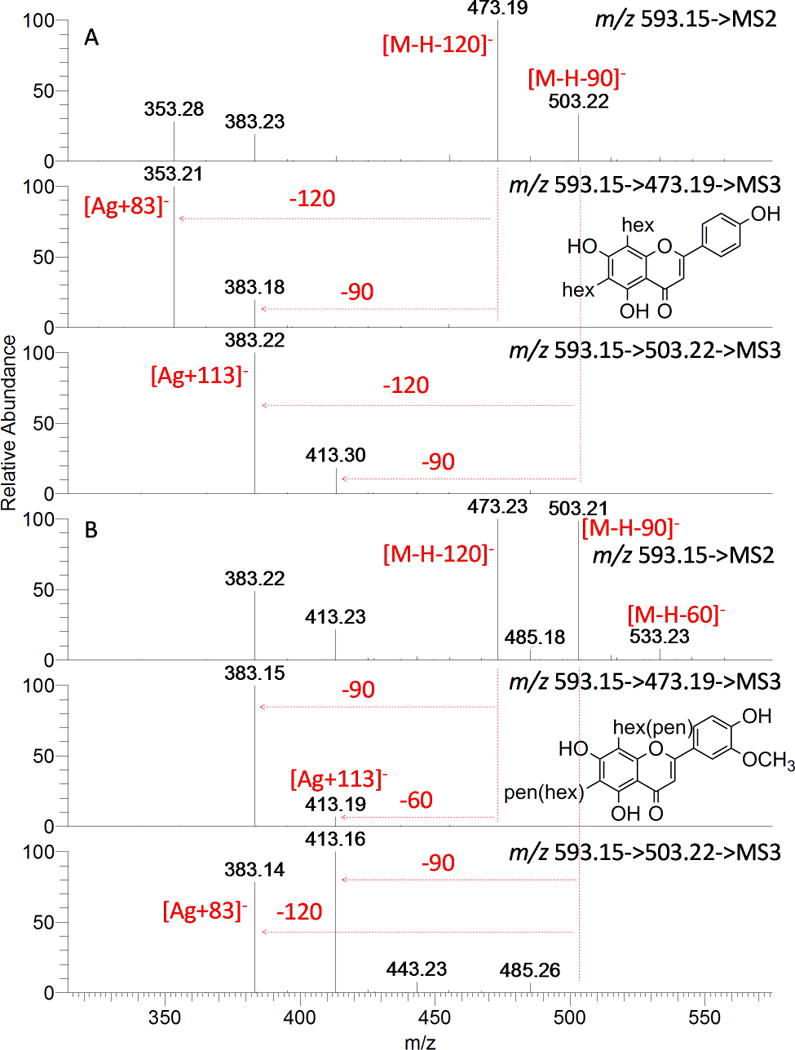

Full scan spectra of compounds D3, D4, D7, D19, D22, D25, and D27 had the deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 593.1512 (C27H29O15). The MS2 and MS3 analyses of these compounds provided a typical fragmentation of di-C-glycosyl flavones, and also indicate two different patterns of aglycone-sugar combination. The multi-stage mass spectra of representative compounds D7 and D27 are shown in Fig. 6. In Fig. 6A, simultaneous neutral loss of 120 and 90 Da from [M-H]− ion at m/z 593 and successive cross-ring cleavage from ions at m/z 473 and 503 suggest the presence of two hexoses; and the ions at m/z 353 (Ag+83) and 383 (Ag+113) indicate the aglycone as a trihydroxyflavone. However, in Fig. 6B, the ion at m/z 533 ([M-H-60]−) in the MS2 spectrum and ions at m/z 413 ([M-H-120-60]−) /383 ([M-H-120-90]−) in the MS3 spectrum of [593→473] reveal the pentose nature of the saccharide; and the ions at m/z 383 (Ag+83) and 413 (Ag+113) indicated the aglycone to be chrysoeriol (MW 300, Table 1). The UV spectra show two maxima at 270 and 334–335 nm for D3, D4 and D7; and at 270 and 348 nm for D19, D22, D25 and D27. These UV data are in accordance to C-glycosyl apigenin and chrysoeriol, respectively.[41, 42] Taking into account the UV and MS information, D3, D4, and D7 were putatively assigned as apigenin 6,8-di-C-hexosides, whereas D19, D22, D25, and D27 were assigned as 6,8-di-C-hexosyl/pentosyl chrysoeriol.

Figure 6.

MS2 and MS3 spectra of compounds D7 (A) and D27 (B).

In a similar way, more 6,8-di-C-glycosyl (hexosyl/pentosyl/deoxyhexosyl) flavones (apigenin/luteolin/chrysoeriol) were characterized and listed in Table 3.

O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavone

Ferreres and co-workers[9, 26] investigated the fragmentation behaviors of O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavones with O-glycosylation on phenolic hydroxyl or on the C-glycosyl residue or combination of both forms by ion trap in the negative mode, and revealed some useful features to characterize them. These features are: the occurrence of an abundant ion Y− ([M-H-132/-146/-162]−) (Fig. 1A) after MS2 fragmentation characterizes the O-glycosylation on phenolic hydroxyls; the preferential fragmentation leading to a relevant Z− ([Y-18]−) (Fig. 1B) fragment is characteristic of 2″-O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl derivatives; and the O-glycosylation on the hydroxyl at 6″ of the sugar moiety from C-glycosylation leads to 0,2X− that implies a global loss of the sugar moiety from O-glycosylation plus the fraction of the sugar moiety from C-glycosylation which contains the carbons 6″–3″ ([M−H-162-120]−, in the case of 6″-O-hexosyl-C-hexosyl derivatives) (Fig. 1C).

The O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavones encountered in wheat germ are more complicated than the model compounds used in the study of Ferreres et al. The identified O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavones in this work are all O-glycosylated C-C-di-glycosyl flavones. The diversity and similarity of these spectra indicate that the differences of fragmentation are derived from not only the position of O- and C-glycosylation, but also the sugar type and even the anomeric configuration of the sugars (Fig. S2, Table 3). Moreover, spectral evidence implies that 3″ or 4″-O-glycosylation may be present as well.

A total of 11 compounds possess the same deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 725.1935 (C32H37O19) with an additional 162.0528 mass shift (compared to compounds D11, D16, and D17 etc.), suggesting an additional O-hexosyl moiety (not caffeoyl, 162.0317). This hypothesis is confirmed by the fragmentation pattern shown in Fig. 7, and more spectra of the representative isomers are shown in Fig. S2. The spectra of T2, T5, and T6 are quite different but have one common feature; the fragment ions at m/z 353 (Ag+83) and 383 (Ag+113) indicate derivatives of 6, 8-di-C-glycosyl apigenin as mentioned above. In Fig. 7A, a global loss of the sugar moiety from O-glycosylation and a fraction of the sugar moiety from C-glycosylation provide 0,2X−H (m/z 443, [M-H-162-120]−) and 0,3X−H (m/z 473, [M-H-162-90]−), suggesting a 6″-O-hexosyl-C-hexosyl structure. The successive loss of 60 and 90 Da resulted from ions at m/z 443 and 473 in the MS3 spectra implies the other C-glycosylated sugar is pentose. Therefore, T2 could be considered as C-(6″-O-hexosyl) hexosyl-C-pentosyl apigenin. The base peak observed in MS2 spectrum of T5 (Fig. 7B) at m/z 563 corresponded to the loss of a hexosyl moiety, in agreement with the O-glycosylation on phenolic hydroxyls; other fragments produced by losing 60, 90, and 120 Da suggest the presence of C-hexosyl-C-pentosyl apigenin. Thus, it was putatively assigned as O-hexosyl-C-hexosyl-C-pentosyl apigenin. The 7-OH in flavones is favored to be glycosylated,[4] but no sufficient evidence was obtained to exclude other sites (e.g. 4′-OH). The predominant ion at m/z 545 (Z ion, [M-H-162-18]−) led T6 to be more likely a 2″-O-hexosylated than 6″-O-hexosylated compound (Fig. 7C). A global loss of the hexosyl moiety and a fraction of C-glycosylation generated a fragment ion at m/z 473 ([M-H-162-90]−) with absence or very scarce presence of an ion at m/z 443 ([M-H-162-120]−). In the MS3 spectra of [725→545] and [725→473] and MS4 spectra of [725→545→527], major fragments generated from the internal cleavage of a hexose by losing 90 and 120 Da are observed. All the information indicates that the O-hexosyl is linked to C-pentosyl, not C-hexosyl, and the C-hexose is unsubstituted. Hence, the ion at m/z 473 ([M-H-162-90]−) was 0,2X−P, not 0,3X−H. The presence of this ion demonstrated the O-hexosyl was linked to position 3″ or 4″ instead of 2″of the C-pentosyl moiety. Compound T6 was putatively assigned as C-(3″or 4″-O-hexosyl) pentosyl-C-hexosyl apigenin, which is reported in wheat for the first time.

Figure 7.

MSn spectra of peaks with [M-H] − ion at m/z 725.19. A: T2; B: T5; and C: T6.

More mono-O-glycosyl-di-C-glycosyl flavones characterized from wheat germ are listed in Table 3.

O-acylated-C-glycosyl flavone

Some plant secondary metabolites occur in the form of glycosides acylated by phenolic acids such as p-coumaric, caffeic, and ferulic acid, etc. The main problem in interpreting the mass spectra of these compounds arises from the fact that the neutral loss of these acyl groups (nominal masses of 146, 162, and 176, respectively) is equal to that of common glycosidic moieties (rhamnose, glucose or galactose and glucuronic acid). For this reason, high resolution MS/MS spectra are necessary for acyl group identification. UV spectra can also help to recognize acylated C-glycosyl flavone. The majority of them show a UV spectrum with an intense band I (approximately 330 nm) and a small band II (approximately 270 nm) as a result of the overlapped UV spectra of flavonoid and cinnamoyl acid.[17] Sinapoyl, feruloyl, p-coumaroyl, syringoyl, and vanilloyl were identified from 21 acylated di- or tri- glycosides (Table 3). Fourteen of them were acylated flavone di-C-glycosides; the remaining seven are acylated mono-O-glycosyl-di-C-glycosyl flavones.

In the MS2 spectra of compounds AD1-AD14, the base peak was produced by loss of the radical acyl and a molecule of water ([M-H-acyl-18]−), with [M-H-acyl]− also detected (Table 3, Fig. 8A). This fragmentation behavior was similar to that observed in C-glycosyl flavones O-glycosylated in position 2″, indicating that the acylation was probably in the 2″-OH of the C-glycosylated sugar. Compound AD7 is illustrated in Fig. 8A. Apart from the [M-H-sinapoyl-18]− and [M-H-sinapoyl]− ions that show up in MS2, cross-ring cleavage ions of the C-glycosyl moiety were observed in the following MS3 and MS4 spectra, indicating a C-hexosyl (−90, −120 Da) and C-pentosyl (−60, −90 Da). The aglycone indicative ions appear as [A+83−18]− and [A+113−18]− instead of [A+83]− and [A+113]− in this category. Previous reports have tried to determine the attached position of acyl group in C-6 or C-8-glycosyl by comparing the relative intensity of cross-ring cleavage ions from a pair of isomers[17] or depending on whether the [M-H-acyl-18]− or [M-H-acyl]− ion was detected as the base peak,[18] But there is not enough evidence to support these conclusions. Therefore, AD7 was determined to be 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-pentosyl-C-hexosyl apigenin.

Figure 8.

MSn spectra of acylated compounds. A: AD7; B: AT1; C: AT4; and D: AT7.

Acylated tri-glycosides (AT1, AT4, and AT7) exhibited large differences in fragmentation patterns as shown in Fig. 8B, 8C, and 8D. The base peak at m/z 739 in AT1 (Fig. 8B) is due to the loss of 162.0528 Da (O-hexosylation on the phenolic hydroxyl), another major ion in the full MS spectrum was m/z 545 (loss of feruloyl+18 and of a hexosyl moiety). It was also the major product ion in MS3 spectrum (901→739), indicating that the acylation had a great chance to be on the 2″-OH of C-glycosylation; neutral loss of 120 Da (901→545→MS3) and 90/60 Da (901→545→425→MS4) typified a C-glycosylated hexose and pentose, respectively. The acyl group of AT4 and AT7 was assigned to be on the 2″-OH of C-glycosylation for their base peak at [M-H-acyl-18]− in their MS2 spectra (Fig.8C, Fig. 8D), just as AD7; but the following fragmentation of ion [M-H-acyl-18]− at m/z 707 demonstrated different glycan structure in these two compounds. For AT4, the product ion at m/z 587 in MS3 of [931→707] generated by cleavage of 120 Da suggested a C-hexosylation; further MS4 fragmentation of m/z 587 gave two major product ions at m/z 425 (loss of hexosyl) and 335 (loss of hexosyl and 0,2X−P cross-ring cleavage), which indicated a C-(3″ or 4″-O-hexosyl) pentosyl moiety. In the case of AT7, ions produced from the internal cleavage of the sugars from C-glycosylation plus hexosyl (−162−120 and −162−90) were detected, providing the evidence of a C-(4″ or 6″-O-hexosyl) hexosyl moiety. Ion [A+83−18]− (m/z 335) and/or [A+113−18]− (m/z 365) in their respective MS4 spectra indicate AT1, AT4, and AT7 have the same aglycone apigenin. Consequently, they were assigned as 2″-O-feruloyl, O-hexosyl-C-pentosyl-C-hexosyl apigenin, 2″-O-sinapoyl, C-(3″ or 4″-O-hexosyl) pentosyl-C-hexosyl apigenin, and 2″-O-feruloyl, C-(4″ or 6″-O-hexosyl) hexosyl-C-pentosyl apigenin.

Conclusions

The combination of UPLC-PDA-ESI/HRMSn and MDF proves to be a powerful and efficient technique in the structural elucidation of four different types of C-glycosyl flavones. MDF based on precisely defined mass defect windows and mass windows removes noise and highlights the targets, enabling MS profiling work more versatile and routine. By using the MSn fragmentation rules of flavone mono-C-glycosides and di-C-glycosides from the standards and previous reports, 72 C-glycosyl flavones were putatively identified in the extract of wheat germ. Accurate mass measurement of MS2 spectra differentiated flavone diglycosides acylated with hydroxycinnamic acid from their isobaric flavone triglycosides. Among the characterized compounds, fourteen were acylated di-C-glycosyl flavones and seven were acylated mono-O-glycosyl-di-C-glycosyl flavones. It should be noted that no MS fragmentation rules of these acylated di-C-glycosyl or mono-O-glycosyl-di-C-glycosyl flavones based on authentic compounds have been previously reported. Our study provides useful information for their structure elucidation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the Agricultural Research Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture and an Interagency Agreement with the Office of Dietary Supplements of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Supporting information may be found in the on line version of this article.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.Curtis BC, Rajaram S, Macpherson HG. Bread wheat: improvement and production. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Courts FL, Williamson G. The occurrence, fate and biological activities of C-glycosyl flavonoids in the human diet. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015;55:1352. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2012.694497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao J, Capanoglu E, Jassbi AR, Miron A. Advance on the Flavonoid C-glycosides and Health Benefits. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2015.1067595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavaliere C, Foglia P, Pastorini E, Samperi R, Laganà A. Identification and mass spectrometric characterization of glycosylated flavonoids in Triticum durum plants by high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:3143. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ioset JR, Urbaniak B, Ndjoko-Ioset K, Wirth J, Martin F, Gruissem W, Hostettmann K, Sautter C. Flavonoid profiling among wild type and related GM wheat varieties. Plant Mol Biol. 2007;65:645. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brazier-Hicks M, Evans KM, Gershater MC, Puschmann H, Steel PG, Edwards R. The C-Glycosylation of Flavonoids in Cereals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wojakowska A, Perkowski J, Goral T, Stobiecki M. Structural characterization of flavonoid glycosides from leaves of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) using LC/MS/MS profiling of the target compounds. J Mass Spectrom. 2013;48:329. doi: 10.1002/jms.3160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Talhi O, Silva AMS. Advances in C-glycosylflavonoid Research. Curr Org Chem. 2012;16:859. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreres F, Gil-Izquierdo A, Andrade PB, Valentao P, Tomas-Barberan FA. Characterization of C-glycosyl flavones O-glycosylated by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2007;1161:214. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.05.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuyckens F, Claeys M. Mass spectrometry in the structural analysis of flavonoids. J Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:1. doi: 10.1002/jms.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ablajan K, Abliz Z, Shang XY, He JM, Zhang RP, Shi JG. Structural characterization of flavonol 3,7-di-O-glycosides and determination of the glycosylation position by using negative ion electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:352. doi: 10.1002/jms.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferreres F, Llorach R, Gil-Izquierdo A. Characterization of the interglycosidic linkage in di-, tri-, tetra- and pentaglycosylated flavonoids and differentiation of positional isomers by liquid chromatography/electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:312. doi: 10.1002/jms.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abranko L, Szilvassy B. Mass spectrometric profiling of flavonoid glycoconjugates possessing isomeric aglycones. J Mass Spectrom. 2015;50:71. doi: 10.1002/jms.3474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang WZ, Qiao X, Bo T, Wang Q, Guo DA, Ye M. Low energy induced homolytic fragmentation of flavonol 3-O-glycosides by negative electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2014;28:385. doi: 10.1002/rcm.6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becchi M, Fraisse D. Fast Atom Bombardment and Fast Atom Bombardment Collision-Activated Dissociation Mass-Analyzed Ion Kinetic-Energy Analysis of C-Glycosidic Flavonoids. Biomed Environ Mass Spectrom. 1989;18:122. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreres F, Silva BM, Andrade PB, Seabra RM, Ferreira MA. Approach to the study of C-glycosyl flavones by ion trap HPLC-PAD-ESI/MS/MS: application to seeds of quince (Cydonia oblonga) Phytochem Anal. 2003;14:352. doi: 10.1002/pca.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferreres F, Gil-Izquierdo A, Vinholes J, Grosso C, Valentao P, Andrade PB. Approach to the study of C-glycosyl flavones acylated with aliphatic and aromatic acids from Spergularia rubra by high-performance liquid chromatography-photodiode array detection/electrospray ionization multi-stage mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25:700. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cao J, Yin C, Qin Y, Cheng Z, Chen D. Approach to the study of flavone di-C-glycosides by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem ion trap mass spectrometry and its application to characterization of flavonoid composition in Viola yedoensis. J Mass Spectrom. 2014;49:1010. doi: 10.1002/jms.3413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dinelli G, Segura-Carretero A, Di Silvestro R, Marotti I, Arraez-Roman D, Benedettelli S, Ghiselli L, Fernadez-Gutierrez A. Profiles of phenolic compounds in modern and old common wheat varieties determined by liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2011;1218:7670. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.05.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu Q, Qiu Y, Beta T. Comparison of Antioxidant Activities of Different Colored Wheat Grains and Analysis of Phenolic Compounds. J Agric Food Chem. 2010;58:9235. doi: 10.1021/jf101700s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dinelli G, Carretero AS, Di Silvestro R, Marotti I, Fu SP, Benedettelli S, Ghiselli L, Gutierrez AF. Determination of phenolic compounds in modern and old varieties of durum wheat using liquid chromatography coupled with time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216:7229. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng P, Zhang M, Harnly J, Luthria D, Chen P. Use of fuzzy chromatography mass spectrometric (FCMS) fingerprinting and chemometric analysis for differentiation of whole-grain and refined wheat (T. aestivum) flour. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2015;407:7875. doi: 10.1007/s00216-015-9007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asenstorfer RE, Wang Y, Mares DJ. Chemical structure of flavonoid compounds in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) flour that contribute to the yellow colour of Asian alkaline noodles. J Cereal Sci. 2006;43:108. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Zhang D, Ray K, Zhu M. Mass defect filter technique and its applications to drug metabolite identification by high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2009;44:999. doi: 10.1002/jms.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu ZM, Wang LQ, Wu J. Mass Defect Filter - A New Tool to Expedite Screening and Dereplication of Natural Products and Generate Natural Product Profiles. Nat Prod J. 2011;1:135. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferreres F, Andrade PB, Valentão P, Gil-Izquierdo A. Further knowledge on barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) leaves O-glycosyl-C-glycosyl flavones by liquid chromatography-UV diode-array detection-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1182:56. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2007.12.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Domon B, Costello C. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconj J. 1988;5:397. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Julian EA, Johnson G, Johnson DK, Donnelly BJ. The glycoflavonoid pigments of wheat, Triticum aestivum, leaves. Phytochemistry. 1971;10:3185. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wagner H, Obermeier G, Chari VM, Galle K. Flavonoid-C-Glycosides From Triticum aestivum L. J Nat Prod. 1980;43:583. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harborne JB, Boardley M, Frost S, Holm G. The Flavonoids in Leaves of Diploid Triticum Species (Gramineae) Plant Syst Evol. 1986;154:251. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feng Y, McDonald C, Vick B. C-glycosylflavones from hard red spring wheat bran. Cereal Chem. 1988;452 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng X, Jiang D, Shan Y, Dai T, Dong Y, Cao W. New flavonoid-C-glycosides from Triticum aestivum. Chem Nat Compd. 2008;44:171. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallardo C, Jiménez L, García-Conesa MT. Hydroxycinnamic acid composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of selected grain fractions. Food Chem. 2006;99:455. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pereira CAM, Yariwake JH, McCullagh M. Distinction of the C-glycosylflavone isomer pairs orientin/isoorientin and vitexin/isovitexin using HPLC-MS exact mass measurement and in-source CID. Phytochem Anal. 2005;16:295. doi: 10.1002/pca.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abranko L, Garcia-Reyes JF, Molina-Diaz A. In-source fragmentation and accurate mass analysis of multiclass flavonoid conjugates by electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2011;46:478. doi: 10.1002/jms.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh A, Kumar S, Bajpai V, Reddy TJ, Rameshkumar KB, Kumar B. Structural characterization of flavonoid C- and O-glycosides in an extract of Adhatoda vasica leaves by liquid chromatography with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2015;29:1095. doi: 10.1002/rcm.7202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li QM, Vandenheuvel H, Dillen L, Claeys M. Differentiation of 6-C-Glycosidic and 8-C-Glycosidic Flavonoids by Positive-Ion Fast-Atom-Bombardment and Tandem Mass-Spectrometry. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1992;21:213. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200230705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishida H, Wakimoto T, Kitao Y, Tanaka S, Miyase T, Nukaya H. Quantitation of Chafurosides A and B in Tea Leaves and Isolation of Prechafurosides A and B from Oolong Tea Leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57:6779. doi: 10.1021/jf900032z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abad-Garcia B, Garmon-Lobato S, Berrueta LA, Gallo B, Vicente F. New features on the fragmentation and differentiation of C-glycosidic flavone isomers by positive electrospray ionization and triple quadrupole mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:1834. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li SS, Wu J, Chen LG, Du H, Xu YJ, Wang LJ, Zhang HJ, Zheng XC, Wang LS. Biogenesis of C-Glycosyl Flavones and Profiling of Flavonoid Glycosides in Lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108860. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piccinelli AL, García Mesa M, Armenteros DM, Alfonso MA, Arevalo AC, Campone L, Rastrelli L. HPLC-PDA-MS and NMR Characterization of C-Glycosyl Flavones in a Hydroalcoholic Extract of Citrus aurantifolia Leaves with Antiplatelet Activity. J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56:1574. doi: 10.1021/jf073485k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gil-Izquierdo A, Riquelme MT, Porras I, Ferreres F. Effect of the Rootstock and Interstock Grafted in Lemon Tree (Citrus limon (L.) Burm.) on the Flavonoid Content of Lemon Juice. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:324. doi: 10.1021/jf0304775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.