Abstract

One of the most common methods for producing recombinant baculovirus for insect cell protein production involves a transposition mediated system invented over 2 decades ago. This Tn7-mediated system, commercially sold as Bac-to-Bac, has proven highly useful for construction of high quality baculovirus, but suffers from a number of drawbacks which reduce the efficiency of the process and limit its utility for high throughput protein production processes. We describe here the creation of Bac-2-the-Future, a 2nd generation Tn7-based system for recombinant baculovirus production which uses optimized expression vectors, new E. coli strains, and enhanced protocols to dramatically enhance the efficiency of the baculovirus production process. The new system which we describe eliminates the need for additional screening of positive clones, improves the efficiency of transposition, and reduces the cost and time required for high throughput baculovirus production. The system is compatible with multiple cloning methodologies, and has been demonstrated to produce baculovirus with equal or better titer and protein productivity than the currently available systems.

Keywords: Baculovirus, insect cells, Tn7 transposition, Bac-to-Bac, protein production

1. Introduction

Currently, insect cell expression of heterologous proteins is one of the primary methods for production of complex mammalian proteins for biochemical, biophysical, and structural studies (Contreras-Gomez et al., 2014; Jarvis, 2009; van Oers et al., 2015). Insect cells have high protein productivity, generate proteins with accurate phosphorylation and other post-translational modifications, and have even been engineered to produce human-like glycosylation of proteins (Harrison and Jarvis, 2006; Jarvis, 2003). While stable insect cell lines can be generated, the majority of insect cell expression work is carried out using baculovirus technology. Baculoviruses are large double-stranded DNA viruses which are capable of lytic infection of insect cells, and which carry strong promoters that can be used to generate large amounts of desired proteins of interest while other viral factors shut down host cell protein synthesis. In order to generate recombinant baculovirus, a number of methods were initially developed utilizing homologous recombination within insect cells to add genes for proteins of interest into the baculovirus genome (Hitchman et al., 2011; Summers, 2006). All of these methods suffered from the need for complex plaque purifications required to eliminate non-recombinant baculovirus, as well as highly complex cloning methods needed to introduce the DNA.

The first major improvement in baculovirus production came with the invention of transposition technology (Bac-to-Bac) for baculovirus production in E. coli. First published over 20 years ago, this technology remains one of the most popular and effective methods today for constructing recombinant baculovirus (Luckow et al., 1993). The basic principle of the technology involves the production of an expression vector containing the baculovirus promoter and gene of interest flanked by recognition sites for the bacterial Tn7 transposase. This entire region is then transferred into a large single-copy DNA, known as a bacmid, which contains the whole AcMNPV genome with an episomal origin of replication allowing it to propagate in E. coli. The transposed bacmid contains the desired expression cassette, and through a process of selection and screening, recombinant bacmids can be isolated, grown, and DNA prepared for transfection of insect cells. To date, this system is the only one which is capable of producing 100% pure recombinant bacmid without issues arising from trans-complementation or homologous recombination, and requires no downstream plaque purification or other manipulations.

The major drawbacks of the original transposition based system fall into several categories. First, proper transposition efficiency is low because transposition can occur into the natural E. coli chromosomal attTn7 site as well as into the bacmid (Leusch et al., 1995). This leads to false positives which need to be screened out. Second, bacmid DNA is often contaminated with variable amounts of expression clone DNA which leads to downstream issues in insect cell transfection. Finally, aspects of Tn7 biology were overlooked or unknown at the time this system was created, leading to a transposition process that is suboptimal. In particular, at the time the system was created, nothing was known about the two alternative methods of transposition of Tn7, only one of which is specific for the attTn7 site (Waddell and Craig, 1988). As the entire Tn7 protein complement is present on the original DH10Bac helped plasmid, alternative non-productive transposition readily occurs with this system. Here we describe an improved 2nd generation system called Bac-2-the-Future (B2F) which contains modified expression vectors, Tn7 transposase helper plasmid, E. coli bacmid strains, and protocols for recombinant baculovirus production. Taken together, the components of the new the B2F system lead to dramatic improvements in baculovirus throughput and help to streamline protein production in insect cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotides for cloning and PCR verification are listed in Table 1 and were generated by Eurofins Genomics and used unless noted otherwise at 200 nM concentration for PCR and 100 nM for sequencing.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotides used in this study. All oligonucleotides were obtained from Eurofins Genomics in desalted, unpurified form

| Primer | Sequence (5′ – 3′) |

|---|---|

| Tn7blockF | AGTTATCCATCGATATCATAACTTCGTATAATGTATGCTATACGAAGTTATTAGGCACCCCAGGCTTTACACTTTATGC |

| Tn7blockR | GACCCTAGCGATATCATAACTTCGTATAGCATACATTATACGAAGTTATTACGCCCCGCCCTGCCACTCATCGC |

| Tn7blockSeq1 | ATGAATGCTCATCCGGAACTCCG |

| Tn7blockSeq2 | GAAATCGTCGTGGTATTCACTCC |

| Tn7genomic1 | GTTGTATGTCTTCGCCGATCAGGATGCGGGTTTTG |

| Tn7genomic2 | CAGTCTGATTTAAATAAGCGTTGATATTCAGTC |

| Tn7genomic3 | CTGCGATGAGTGGCAGGGCGGGG |

| Tn7genomic4 | TCCGGATGAGCATTCATCAGGCG |

| oriR6K-start | AGAGGCTCTAAGGGCTTCTCAGTGCG |

| oriR6K-end | CTCGCTCCAAGCTTCTGAAGATCAGCAGTTCAACCTGTTG |

| His-top | GATCTCACCATCACCATCACCATGGATCCGATATCA |

| His-bottom | AATTTGATATCGGATCCATGGTGATGGTGATGGTGA |

| GST-start | CGGATTTAGAGATCTCATCACCATCACCATCACGGCGCCCCTATACTAGG |

| GST-stop | CATCGCAATAGGATCCACGCGGAACCAGATCCGATTTTGGAGGATGG |

| MBP-start | CGGATTTAGAGATCTCATCACCATCACCATCACGGCAAAATCGAAGAAGG |

| MBP-stop | CATCGCAATAGGATCCCGAATTAGTCTGCGCGTCTTTCAGGGCTTC |

| Baccheck-R | GTGCTGCAAGGCGATTAAGT |

| Baccheck-F | TGTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATA |

| Baccheck-BtB-L | ATCAGCCGGACTCCGATTA |

| Baccheck-Btb-R | CCCACACCTCCCCCTGAACCTG |

| Baccheck-B2F-L | AGCGTGGGTCTCGCGGTATCATT |

| Baccheck-B2F-R | AAATGCCAGCCGATCGGGCTGGC |

2.2 Construction of expression vectors

To generate the new R982-X01 helper plasmid, the pMon7124 vector was isolated from DH10Bac cells (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) after overnight growth at 37C in media containing 20 ug/ml tetracycline. Plasmid DNA was isolated with the QiaSpin Plasmid miniprep kit (Qiagen), and digested with a combination of PacI and EcoRI restriction enzymes (New England Biolabs) for 2 hours at 37C according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This digestion removed the TnsE sequence and other extraneous DNA, and the backbone was resealed by ligation using T4 Quick Ligase, and the final construct was completely sequence validated.

Construction of the parental pDP1381 vector was carried out by cloning the origin of replication of pR10, an oriR6kγ backbone vector (generous gift from Rick Boyce) by PCR amplification with oriR6K-start and oriR6K-stop primers. This PCR product was ligated into a HindIII site in a synthetic DNA construct generated by DNA2.0 containing an ampicillin resistance gene, Tn7L and Tn7R transposition sites, a polyhedrin promoter, and appropriate restriction enzyme polylinkers. The final plasmid was transformed into DE14 cells and selected on media containing 100 ug/ml ampicillin. The complete sequence of pDP1381 was verified to ensure no cloning artifacts had been introduced.

Aminoterminal protein expression fusion vectors were generated from pDP1381 by introduction of fusion tags into the unique BamH1 site in pDP1381. A His6 fusion vector (pDP1385) was generated by insertion of annealed oligonucleotides (His-top and His-bottom) with sticky ends compatible with the BamHI sequence. The His6-GST (pDP1387) and His6-MBP (pDP1386) vectors were made by PCR amplification of the fusion tags from Gateway vectors (pDest-565 and pDest-566 respectively) using either BamHI or BglII sites on the oligonucleotides. In all cases, the final vectors were fully sequence validated throughout the tag and backbone sequences.

Gateway versions of the pDP vectors were constructed by digesting the parental plasmids with EcoRV, and ligation of the Gateway Reading Frame A cassette into the blunt ended site. This allows in-frame insertion of the Gateway cassette, which is then selected in DE15 cells in the presence of 100 ug/ml ampicillin and 15 ug/ml chloramphenicol. After verification of the proper direction of insertion, final clones (pDest-381 for native, pDest-385 for His6 fusion, pDest-386 for His6-MBP fusion, and pDest-387 for His6-GST fusion) were sequenced to ensure the Gateway junctions were properly cloned and were in frame with the fusion tags.

Multisite Gateway vectors for use with the FNL combinatorial cloning platform (CCP) were generated by PmeI digestion of pDP1381, which eliminates the polyhedrin promoter and polylinker regions of the construct, followed by ligation of Gateway cassettes for either attR4-attR2 (pDest-382) or attR4-attR3 (pDest-383) versions of the CCP. Final clones were selected in DE15 cells, verified for directionality, and sequence confirmed.

2.3 Construction of DE26 B2F strain

In order to construct the blocked attTn7 site strain, a blocking construct was first engineered by introducing the CAT gene encoding chloramphenicol acetyl transferase into an oriR6kγ backbone vector which contains flanking Tn7L and Tn7R sites. The nonessential parts of this vector were removed by a dual EcoRV/HpaI digest, and the CAT gene was amplified by PCR with primers Tn7blockL and Tn7blockR containing EcoRV sites to allow blunt end ligation of the two products. These were ligated using T4 Quick Ligase (New England Biolabs), and transformed into E. coli DE14 which were plated on media containing 100 ug/ml ampicillin and 20 ug/ml chloramphenicol. After overnight incubation, colonies were isolated and grown in liquid media, and plasmid DNA was prepared. Final plasmid DNA was sequence verified using Tn7blockSeq1 and Tn7blockSeq2 primers to ensure the integrity of the CAT-containing insert and the Tn7 transposition sites.

The blocking construct was transformed into E. coli DE24 cells containing the Tn7 transposase helper plasmid (R982-X01) and transformations were plated on 20 ug/ml chloramphenicol after 5 hours of growth to permit transposition to occur. After overnight growth at 37C, colonies were selected and verified for blocking plasmid loss by streaking onto new plates containing 100 ug/ml ampicillin. Clones which did not grow on ampicillin containing media were used to generate genomic DNA preps using the GenElute Genomic DNA kit (Sigma), which were then used for PCR amplification to test for proper insertion of the CAT gene. All clones chosen showed the correct amplification of multiplex PCR products (using primers Tn7genomic1, 2, 3, and 4) showing that transposition occurred into the attTn7 region as expected. PCR products were cleaned using the QiaQuick PCR Purification kit (Qiagen) and were subjected to Sanger sequencing to verify the junctions. As expected, insertion into the attTn7 site occurred at the exact site identified in the literature. Electrocompetent cells were made from one of these clones, and the bMon14272 bacmid isolated from DH10Bac cells was introduced by electroporation. This final strain, called DE26, was selected on 50 ug/ml kanamycin and 20 ug/ml tetracycline, and serves as the main B2F bacmid production strain.

2.4 Recombinant bacmid production

All recombinant bacmid production was carried out using the manufacturer’s instructions for the Bac-to-Bac system (Life Technologies). In brief, expression clone DNA was transformed into competent DH10Bac or DE26 cells, heat shocked at 42C for 45 seconds, and diluted 1:20 into LB media. These samples were allowed to grow for 4 hours at 37C with vigorous shaking (under normal conditions) or a range of 0–4 hours for timecourse experiments. After this time, various dilutions of the culture were plated on selective media. For normal experiments the media containing 50 ug/ml kanamycin, 100 ug/ml ampicillin (B2F) or 15 ug/ml gentamycin (DH10Bac), and in the case of blue/white selection media, 60 ug/ml X-gal and 100 ug/ml IPTG. After overnight growth, colonies were either restreaked to identical plates for an additional overnight growth before screening for color, or were simply used to pick colonies for bacmid production.

Bacmid DNA was generated by alkaline lysis miniprep from 2 ml of culture using a standard alkaline lysis process. Final bacmid samples were dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 0.1 mM EDTA) and were used for PCR verification of proper transposition. The PCR utilizes a multiplexed approach with 4 primers which amplify fragments from the left and right junctions of the transposition regions. These fragments begin in the bacmid outside of the transposition region and cross the junctions into the backbone of the transfer vector. A positive result yields two bands of known sizes for proper insertions; a negative result yields a single 300 bp band representative of an empty Tn7 insertion site. PCR amplification was done with Phusion polymerase (New England Biolabs) under standard conditions, with 20 cycles of amplification and extension time of 30 sec per cycle. Bac-to-Bac vectors were analyzed using a combination of the Baccheck-F, Baccheck-R, Baccheck-BtB-L and Baccheck-BtB-R primers. B2F vectors were analyzed with a combination of the Baccheck-F, Baccheck-R, Baccheck-B2F-L and Baccheck-B2F-R primers

2.5 Baculovirus production and insect cell protein expression

Bacmid DNA was used to generate baculovirus particles using a previously published procedure (Hopkins et al., 2010). Viruses were titered using the Sf9-ET cell line (Hopkins and Esposito, 2009), and were used for subsequent protein production by the “early detection” method first described in (Hopkins et al., 2010). Expression was carried out in Tni-FNL cells, our in-house variant of the Trichoplusia ni insect cell line, with growth for 72 hrs at 21C. Final cultures were analyzed for protein production by centrifugation of samples and resuspension of pellets in SDS-PAGE buffer prior to electrophoresis on 4–20% Tris-glycine Criterion gels (Biorad).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Construction of new baculovirus expression vectors

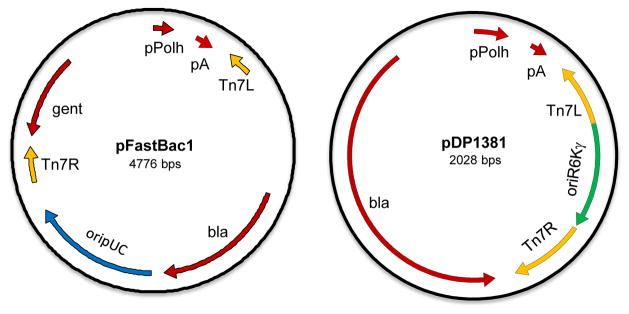

The standard backbone vectors for the original Bac-to-Bac system are the pFastBac series of plasmids. These vectors unnecessarily contain two separate antibiotic selection markers: an ampicillin resistance marker in the plasmid backbone and a gentamycin resistance marker which is transferred to the bacmid during transposition (see Fig. 1 for plasmid schematics). The gentamycin resistance gene is particularly problematic as it contains a direct repeat at its 5′ end which can readily recombine in E. coli to create a frameshift and lead to gentamycin sensitivity, thus causing issues in efficiency of selection. To reduce the overall vector size and eliminate the redundant selection marker, the gentamycin region from pFastBac was removed and a 2nd generation vector (pDP1381) was constructed with ampicillin selection within the Tn7 cassette.

Fig. 1. Schematic comparison of Bac-to-Bac and B2F expression vectors.

Shown are the vector map of pFastBac1 (left) and pDP1381 (right), which serve as the basic expression vectors for the two systems. Important regions are highlighted including the polyhedrin promoter (pPolh), polyadenylation site (pA), Tn7 left and right transposition sites (Tn7L/Tn7R), ampicillin resistance gene (bla), gentamycin resistance gene (gent), pUC origin of replication (oripUC) and R6Kγ origin of replication (oriR6Kγ).

In addition, pFastBac vectors are capable of replication in the standard host strains used for transposition and therefore untransposed expression vectors are often present in the final bacmid prep (sometimes as much as 100x as much by mass as the actual bacmid DNA). Insect cell transfection using either cationic polymers or lipid reagents is exquisitely sensitive to DNA concentration, and this variable amount of expression clone DNA can cause serious reproducibility issues with insect cell transfection leading to erratic or reduced titer of virus.

To eliminate this problem, several methods have been explored by other laboratories. Olins et al. showed that a temperature sensitive origin could be used to eliminate DNA carryover (Leusch et al., 1995). However, such plasmids are prone to instability issues and temperature shifting is not always amenable to high-throughput processes. Airenne et al. utilized a sucrose-sensitivity system containing the SacB gene as a method to reduce carryover DNA (Airenne et al., 2003). While this system has some advantages over the temperature shift process, SacB counterselection often has problems related to sucrose insensitivity, particularly in liquid growth. This could have a deleterious effect on high-throughput pooled methods that do not involved plating on solid media. Therefore, we chose to use the R6Kγ origin of replication, which restricts plasmid replication to E. coli strains carrying the pir gene (Kolter and Helinski, 1982; Mukhopadhyay et al., 1986; Patel and Bastia, 1986). This origin has a very low copy number, which is also a benefit to this system in reducing plasmid levels, and is smaller than the pUC origin which further reduces the size of the expression vector. These vectors and their derivatives can be maintained in any strain which carries the pir gene (we use a DH10B derivative called DE14 for standard vectors and a DB3.1 derivative called DE15 for Gateway vectors—see Table 3 for more details).

Table 3.

E. coli strains used in this study

| Strain | Purpose | Genotype |

|---|---|---|

| DE14 | B2F vector propagation | DH10B pir |

| DE15 | B2F Gateway vector propagation | DB3.1 pir |

| DE24 | Tn7 site blocking strain | DH10B R982-X01(TetR) |

| DE26 | Bacmid production | DH10B attTn7::block bMon14272(KanR) R982-X01(TetR) |

The final pDP1381 construct (Fig. 1) is only 2 kbp in size (less than half the size of the pFastBac construct), and contains all of the pieces necessary for transposition of genes of interest. In addition, the multiple cloning site downstream of the polyhedrin promoter was engineered for backwards compatibility with pFastBac vectors ensuring that the same restriction sites were available for restriction-based cloning methods. New restriction sites were engineered into the vector to permit the use of ligation-independent cloning (LIC) modifications if desired. Additional vectors were constructed to support production of aminoterminally tagged proteins with either His6, His6-GST (glutathione-S-transferase), or His6-MBP (maltose-binding protein) fusions. Details of these vectors can be found in Table 2. In addition to restriction-based vectors, we have also constructed a series of Gateway recombinational cloning vectors for higher throughput protein production. Several of these (pDest-381, 385, and 387) mimic Gateway vectors originally produced by Life Technologies for baculovirus protein production. Others are designed for use with our combinatorial cloning platform (Wall et al., 2014) which allows more flexibility in promoter and fusion tag options.

Table 2.

B2F vectors constructed in this study. Vectors names are listed along with the vector types [REaL: restriction enzyme and ligase cloning, LIC: ligase-independent cloning, Gateway-CCP: FNLCR combinatorial cloning platform (Wall et al., 2014)], the promoter present in the vector, and a brief description of the function of the vector

| Vector | Cloning type | Promoter | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| pDP1381 | REaL/LIC | polyhedrin | native expression, pFastBac1 cloning compatibility |

| pDP1385 | REaL/LIC | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6 fusion |

| pDP1386 | REaL/LIC | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6-MBP fusion |

| pDP1387 | REaL/LIC | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6-GST fusion |

| pDest-381 | Gateway | polyhedrin | native expression, equivalent to pDest-8 |

| pDest-382 | Gateway-CCP | none | attR4-attR2 cassette for combinatorial cloning |

| pDest-383 | Gateway-CCP | none | attR4-attR3 cassette for combinatorial cloning |

| pDest-385 | Gateway | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6 fusion, equivalent to pDest-10 |

| pDest-386 | Gateway | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6-MBP fusion |

| pDest-387 | Gateway | polyhedrin | aminoterminal His6-GST fusion, equivalent to pDest-20 |

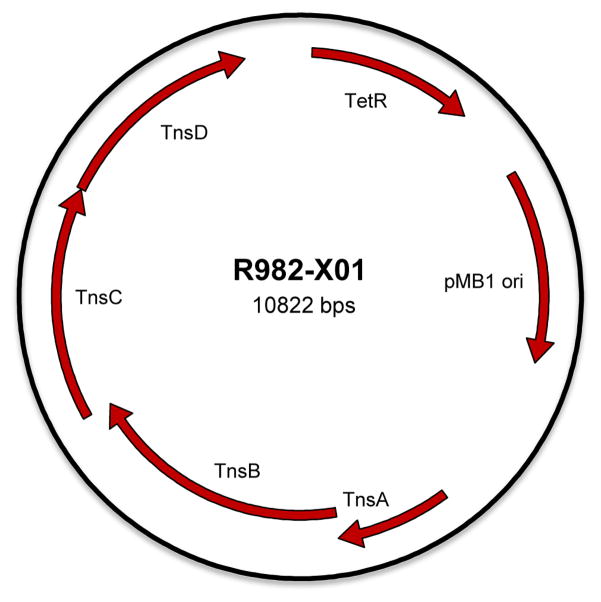

3.2 Construction of new Tn7 transposase delivery vector

The original helper plasmid in the Bac-to-Bac system which delivers the Tn7 transposase functions contains the entire Tn7 transposase gene segment encoding for all 5 transposition proteins (TnsABCDE). At the time the system was created, the role of some of these proteins was unclear, but it is now known that TnsAB form the active transposase, TnsC delivers that transposase to the DNA target, and TnsD and TnsE represent DNA binding proteins for two very different types of transposition (Peters and Craig, 2001; Skelding et al., 2003; Waddell and Craig, 1988). TnsD-mediated transposition specifically into the attTn7 site of the E. coli chromosome allows the transposon to reproduce vertically as cells divide (Mitra et al., 2010). TnsE-mediated transposition allows horizontal transmission by focusing transposition into conjugative plasmids to spread to other bacteria (Peters and Craig, 2000). Since the original system contains all 5 Tn7 genes, there is a high likelihood of horizontal transposition into the bacmid (which is actually a large conjugative plasmid) leading to nonproductive transposition, or even possibly to damaged baculovirus genomes with Tn7 insertions in unwanted places. Therefore, we constructed a new helper, R982-X01, in which we removed the TnsE gene to force transposition to occur exclusively through the site-specific TnsD pathway (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Vector map of B2F Tn7 tranposition helper vector.

The vector map of R982-X01 is shown, highlighting the genes in the Tn7 pathway (TnsA/B/C/D), the strong lac promoter (pLac), the tetracycline resistance marker (TetR), and the pMB1 low-copy origin of replication (pMB1 ori).

3.3 Construction of new E. coli bacmid strain

DH10Bac cells contain a fully functional chromosomal copy of the attTn7 site near the E. coli glmS gene (Oppon et al., 1998). As has been established my many groups, this permits some percentage of the transposition reactions to insert at this locus and potentially produces false positives with selection (Airenne et al., 2003; Leusch et al., 1995). To eliminate this possibility, we constructed a DH10B strain derivative called DE24 with the attTn7 site in the chromosome blocked. Blocking was carried out using a Tn7 insertion of the chloramphenicol gene and was sequence verified to ensure proper blockage of the insertion site in the new cell line. The new R982-X01 helper plasmid was transformed along with the wildtype AcMNPV bacmid into the DE24 cell line to generate the DE26 bacmid production cell line. (See Table 3 for strain details). This strain contains the optimized helper plasmid to drive transposition to be site-specific, as well as the blocked chromosomal Tn7 transposition site to reduce false positives with selection.

3.4 B2F system improvements to bacmid production and quality

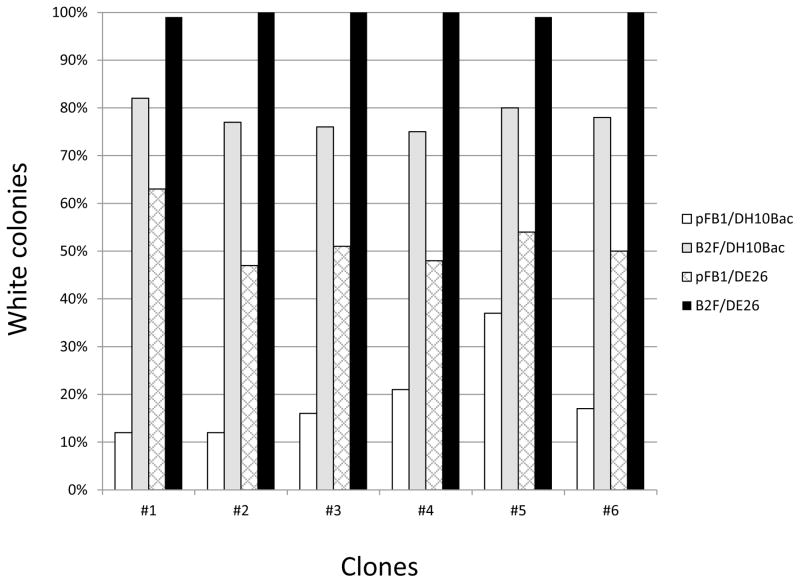

In order to demonstrate improvements in baculovirus production using the B2F system, we carried out a series of transformations to compare vectors and strains from B2F and Bac-to-Bac. 6 different human genes of interest varying in size from 400 bp to 2.7 kB were cloned into standard pFastBac backbones or the analogous B2F backbones and used to transform either DH10Bac or DE26 cells using the standard Bac-to-Bac 4-hour transformation protocol. Transformations were plated in varying dilutions on the appropriate antibiotic media with blue/white selection and after overnight growth, colonies were counted and assessed for color. The results are shown in Fig. 3. Use of the new B2F vectors increases the percentage of correct colonies by approximately 4-fold on average (compare white and grey bars). This change is mainly due to the elimination of positive colonies produced by plasmid replication in the DH10Bac cells. In the absence of transposition of the marker, any ampicillin resistant plasmids that remain will fail to replicate in the pir- host. Remaining blue colonies here are presumably due to transposition into the wrong location; this is borne out by comparison of the data shown in the white and hatched bars which show an approximately 3-fold increase in the percentage of correct colonies using the new host strain lacking a Tn7 site in the E. coli chromosome. These values compare well to previously published data with blocked attTn7 sites (Airenne et al., 2003; Leusch et al., 1995). The black bars show the result of combining the new vector and strain—here it is clear that nearly all of the clones produced are white colonies representing correctly transposed bacmid DNA. To further validate this result, 8 white colonies were chosen from each of these plates and bacmid DNA was prepared. PCR checks were used to validate proper transposition, and in all cases 100% of the chosen white colonies represented proper transposition into the bacmid (data not shown).

Fig. 3. B2F vector and strain combination enhances production of recombinant bacmids.

The graph shows the percentage of white (correct) colonies obtained from standard 4 hour transformations of 6 different baculovirus expression clones. Total colony counts were greater than 200 for each sample. Vectors used were pFastBac1 (pFB1, white and hatched bars) or pDP1381 (B2F, grey and black bars), strains were standard DH10Bac (white and grey bars) or DE26 (hatched and black bars).

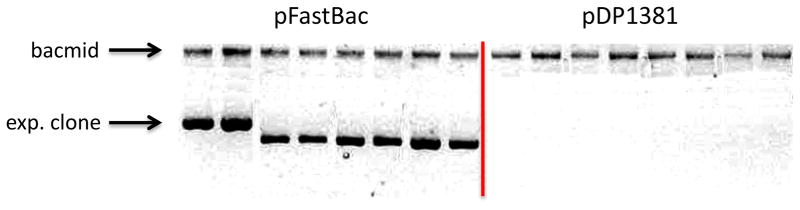

A second advantage to this system is seen in Fig. 4, where bacmid DNA preparations from several clones using pFastBac or B2F backbones is compared. Bacmid preparations from the original Bac-to-Bac system always show the presence of a significant amount of expression clone DNA. The level of plasmid produced is highly variable (compare lanes 1 and 3 in which there is likely a 5-fold difference in DNA concentration), and overall levels of plasmid DNA can easily reach 2 ug/ml due to the very high copy pUC origin of replication. This represents a significant percentage of the total DNA, makes calculation of bacmid DNA concentration impossible, and can significantly affect insect cell transfection efficiency. The B2F vectors, on the other hand, show a complete absence of any expression clone DNA in all preparations. Because this strain does not contain the pir gene, replication of the expression clone DNA carrying the R6Kg origin of replication is not supported in this host. Thus, the DNA coming from these preparations contains no DNA other than the bacmid DNA, making consistent transfection much more likely. Note also that there is also no observed contamination from helper plasmid DNA in these samples—in general we find that helper plasmid DNA is rapidly lost in the absence of selection with tetracycline and we rarely see any detectable helper plasmid in final bacmid samples.

Fig. 4. Elimination of carryover expression clone DNA using the B2F system.

Alkaline lysis bacmid preparations were carried out on 16 different clones from transposition reactions using pFastBac or pDP1381 vectors. Samples of DNA from these preparations were separated on a 0.7% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The positions of the bacmid DNA and the expression clone DNA are shown by the arrows.

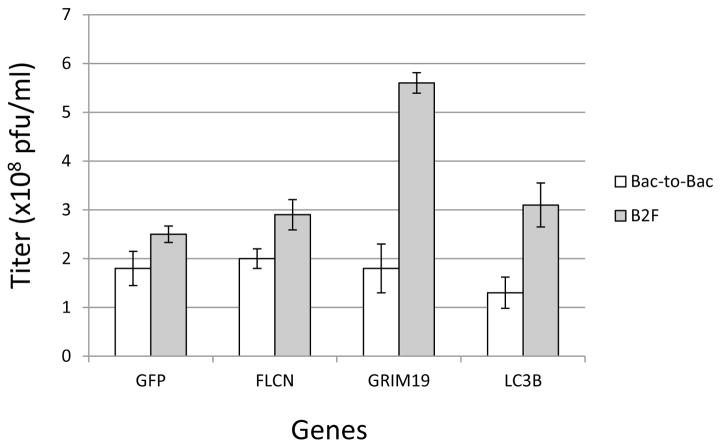

3.5 Baculovirus titer data

In order to verify that the B2F system produces equivalent baculovirus to the original Bac-to-Bac system, we carried out a series of baculovirus productions from the new system and compared the viruses produced. Fig. 5 shows that the titers of 4 different viruses produced using Bac-to-Bac or B2F were very similar—in all cases, the titer of the B2F viruses were slightly higher (1.4 to 3.1 fold) than their Bac-to-Bac counterparts. We believe that the higher titer is likely due in part to the increased transfection efficiency due to the lack of carryover non-productive expression clone DNA. We have continuously observed titers as good as or better than those seen using the Bac-to-Bac system. No other differences were observed between viruses produced in the two systems—overall insect cell expression parameters were similar, and there were no observable phenotypic difference in the viruses (data not shown).

Fig. 5. Comparison of baculovirus titers using the two systems.

Titers of baculovirus stocks generated from bacmid DNA produced in the Bac-to-Bac system (pDest-8/DH10Bac) or the B2F system (pDest-382/DE26) are shown. Titer data was generated using the Sf9-ET cell line (Hopkins and Esposito, 2009) and are measured in plaque-forming units (pfu) per milliliter. For each protein, two independent virus productions were carried out in each vector, and the average titer for the two replicates is plotted along with the standard error.

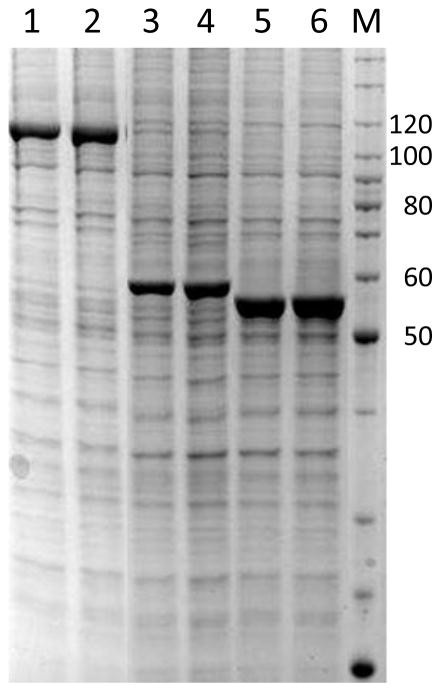

3.6 Protein Data

Since the ultimate use of these baculovirus vectors is often the production of recombinant proteins, we also wanted to ensure that the new B2F system generated viruses which produce similar levels of protein to the current vectors in the Bac-to-Bac system. To do this, a series of Gateway Entry clones for test proteins which have been heavily utilized in our laboratory were introduced into pDest-636 (Bac-to-Bac His6-MBP fusion vector) and pDest-386 (B2F His6-MBP fusion vector) and baculovirus were generated and titered. These titered viruses were used to infect Tni-FNL cells at a multiplicity of infection of 3 and were harvested after 72 hours of growth at 21C. Data for three test proteins are shown in Fig. 6. In each case, the two different systems produced protein of the same molecular weight, quality, and yield. Similar results have been obtained using comparisons of other B2F and Bac-to-Bac vectors (data not shown) demonstrating that the two systems are equivalent for protein production.

Fig. 6. Comparison of protein production with B2F and Bac-to-Bac vectors.

Expression cultures of Tni-FNL cells containing three different His-MBP fusion test proteins in either B2F vector pDest-386 (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or Bac-to-Bac vector pDest-636 (lanes 2, 4, and 6) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Lane M contains Benchmark protein ladder (Thermo Fisher). Expected sizes of the expressed proteins are 114 kDa (lanes 1/2), 58 kDa (lanes 3/4), and 55 kDa (lanes 5/6).

3.7 Additional Protocol Optimization

As one of the major goals of improving the baculovirus production system was to enhance high-throughput protein production, we investigated the details of the protocols for bacmid production to further streamline the process. Elimination of blue-white screening already reduces the need for the extra day of repeat colony streaking which was formerly needed to avoid picking mixed population colonies. However, the protocol still includes a lengthy period of post-transformation growth to generate high levels of transposition. We initially investigated this timecourse by comparing the effect of 2, 3, and 4 hour post-transformation growth on colony counts. As seen in Table 4, shorter timepoints produced even lower percentages of correct colonies using the Bac-to-Bac system. However, the B2F system does not produce any incorrect blue colonies, and therefore, shorter times can be used for transformation with no effect on the accuracy of the colonies obtained. As we still observed significant colony counts with a 2 hour incubation (>5000 colonies per transformation), we decided to investigate further reduction in transformation time. Gentamycin resistance requires some growth prior to selection in order to prevent antibiotic-mediated ribosomal disruption from prohibiting antibiotic resistance. However, since B2F no longer uses gentamycin and since ampicillin resistance can develop during plating, we were able to carry out transformations without any growth prior to selection (direct plating after heat shock). Such transformations still resulted in >1000 colonies per transformation from moderately competent (1 × 108 cfu/ml) DE26 cells (data not shown), which is more than a sufficient number of transformants for high throughput bacmid production or liquid pooled production.

Table 4.

Timecourse of transformations of 2 analogous baculovirus expression clones. Both clones contain a polyhedrin promoter and GFP gene. Transformations were carried out as described in Materials and Methods, with growth after heat shock continued at 37C for the time shown prior to plating 0.2% of the total transformation on selective media. Plates were incubated for 16 hours at 37C prior to colony counts

| Clone | Timepoint | White Colonies | Blue Colonies | Total Colonies | Percentage White |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pEL101-008 in DH10Bac | 2 hours | 9 | 300 | 309 | 2.9% |

| 3 hours | 28 | 400 | 428 | 6.5% | |

| 4 hours | 40 | 500 | 540 | 7.4% | |

| R951-M01-382 in DE26 | 2 hours | 17 | 0 | 17 | 100% |

| 3 hours | 30 | 0 | 30 | 100% | |

| 4 hours | 93 | 0 | 93 | 100% |

4. Conclusions

The Bac-to-Bac system was the gold standard for production of recombinant baculovirus for several decades. While the system has been highly effective, modern high-throughput protein production processes will benefit from the improvements we have discussed here. In particular, further improvements to the baculovirus system will likely come from systems biology approaches including large-scale genomic modification of the virus or host strains, or high-throughput screening of mutants in genes related to protein production or promoters/elements involved in transcription. In our laboratory, we have already seen effects of altering the location of recombinant DNA insertion into the baculovirus as well as improvements to protein expression by modifications of the polyhedrin promoter sequence. Carrying out large scale engineering of the system will greatly benefit from a more robust and high-throughput method of baculovirus construction. The new B2F system not only reduces the time and labor to generate virus by a significant amount, but also eliminates selection on expensive media, all without compromising the quality of virus produced, and the quantity and quality of downstream protein production.

Highlights.

A modified set of vectors and strains improves baculovirus production

Transposition frequency can be enhanced by vector and strain engineering

Optimized protocols permit higher throughput baculovirus production

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical support of Ralph Hopkins, Cammi Bittner, and Matt Drew for baculovirus production and insect cell expression culture work. This project has been funded in whole or in part with Federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract number HHSN261200800001E. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Vectors and strains described in this manuscript are freely available to academic and non-profit researchers by contacting the authors, and some B2F vectors will shortly be available at Addgene (http://www.addgene.org). For-profit companies that are interested in obtaining B2F materials should contact the National Cancer Institute Office of Technology Transfer.

Abbreviations

- AcMNPV

Autographa californica multiple nucleopolyhedrovirus

- GST

glutathione-S-transferase

- MBP

maltose-binding protein

- CCP

combinatorial cloning platform

- cfu

colony forming units

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Airenne KJ, Peltomaa E, Hytonen VP, Laitinen OH, Yla-Herttuala S. Improved generation of recombinant baculovirus genomes in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:e101. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras-Gomez A, Sanchez-Miron A, Garcia-Camacho F, Molina-Grima E, Chisti Y. Protein production using the baculovirus-insect cell expression system. Biotechnol Prog. 2014;30:1–18. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RL, Jarvis DL. Protein N-glycosylation in the baculovirus-insect cell expression system and engineering of insect cells to produce “mammalianized” recombinant glycoproteins. Adv Virus Res. 2006;68:159–191. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)68005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchman RB, Locanto E, Possee RD, King LA. Optimizing the baculovirus expression vector system. Methods. 2011;55:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins R, Esposito D. A rapid method for titrating baculovirus stocks using the Sf-9 Easy Titer cell line. Biotechniques. 2009;47:785–788. doi: 10.2144/000113238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins R, Esposito D, Gillette W. Widening the bottleneck: increasing success in protein expression and purification. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis DL. Developing baculovirus-insect cell expression systems for humanized recombinant glycoprotein production. Virology. 2003;310:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00120-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis DL. Baculovirus-insect cell expression systems. Methods Enzymol. 2009;463:191–222. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(09)63014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolter R, Helinski DR. Plasmid R6K DNA replication. II. Direct nucleotide sequence repeats are required for an active gamma-origin. J Mol Biol. 1982;161:45–56. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(82)90277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leusch MS, Lee SC, Olins PO. A novel host-vector system for direct selection of recombinant baculoviruses (bacmids) in Escherichia coli. Gene. 1995;160:191–194. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00233-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckow VA, Lee SC, Barry GF, Olins PO. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J Virol. 1993;67:4566–4579. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.8.4566-4579.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitra R, McKenzie GJ, Yi L, Lee CA, Craig NL. Characterization of the TnsD-attTn7 complex that promotes site-specific insertion of Tn7. Mob DNA. 2010;1:18. doi: 10.1186/1759-8753-1-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay P, Filutowicz M, Helinski DR. Replication from one of the three origins of the plasmid R6K requires coupled expression of two plasmid-encoded proteins. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9534–9539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppon JC, Sarnovsky RJ, Craig NL, Rawlings DE. A Tn7-like transposon is present in the glmUS region of the obligately chemoautolithotrophic bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3007–3012. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.11.3007-3012.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel I, Bastia D. A replication origin is turned off by an origin-“silencer” sequence. Cell. 1986;47:785–792. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JE, Craig NL. Tn7 transposes proximal to DNA double-strand breaks and into regions where chromosomal DNA replication terminates. Mol Cell. 2000;6:573–582. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JE, Craig NL. Tn7: smarter than we thought. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:806–814. doi: 10.1038/35099006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skelding Z, Queen-Baker J, Craig NL. Alternative interactions between the Tn7 transposase and the Tn7 target DNA binding protein regulate target immunity and transposition. EMBO J. 2003;22:5904–5917. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers MD. Milestones leading to the genetic engineering of baculoviruses as expression vector systems and viral pesticides. Adv Virus Res. 2006;68:3–73. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)68001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oers MM, Pijlman GP, Vlak JM. Thirty years of baculovirus-insect cell protein expression: from dark horse to mainstream technology. J Gen Virol. 2015;96:6–23. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.067108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell CS, Craig NL. Tn7 transposition: two transposition pathways directed by five Tn7-encoded genes. Genes Dev. 1988;2:137–149. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall VE, Garvey LA, Mehalko JL, Procter LV, Esposito D. Combinatorial assembly of clone libraries using site-specific recombination. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1116:193–208. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-764-8_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]