Abstract

In contrast to the well-characterized effects of specialized proresolving lipid mediators (SPMs) derived from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), little is known about the metabolic fate of the intermediary long-chain (LC) n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). In this double blind crossover study, shifts in circulating levels of n-3 and n-6 PUFA-derived bioactive lipid mediators were quantified by an unbiased liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry lipidomic approach. Plasma was obtained from human subjects before and after 7 d of supplementation with pure n-3 DPA, n-3 EPA or placebo (olive oil). DPA supplementation increased the SPM resolvin D5n-3DPA (RvD5n-3DPA) and maresin (MaR)-1, the DHA vicinal diol 19,20-dihydroxy-DPA and n-6 PUFA derived 15-keto-PG E2 (15-keto-PGE2). EPA supplementation had no effect on any plasma DPA or DHA derived mediators, but markedly elevated monohydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acids (HEPEs), including the e-series resolvin (RvE) precursor 18-HEPE; effects not observed with DPA supplementation. These data show that dietary n-3 DPA and EPA have highly divergent effects on human lipid mediator profile, with no overlap in PUFA metabolites formed. The recently uncovered biologic activity of n-3 DPA docosanoids and their marked modulation by dietary DPA intake reveals a unique and specific role of n-3 DPA in human physiology.—Markworth, J. F., Kaur, G., Miller, E. G., Larsen, A. E., Sinclair, A. J., Maddipati, K. R., Cameron-Smith, D. Divergent shifts in lipid mediator profile following supplementation with n-3 docosapentaenoic acid and eicosapentaenoic acid.

Keywords: eicosanoids, fish oil, inflammation, lipidomics, omega-3 fatty acids

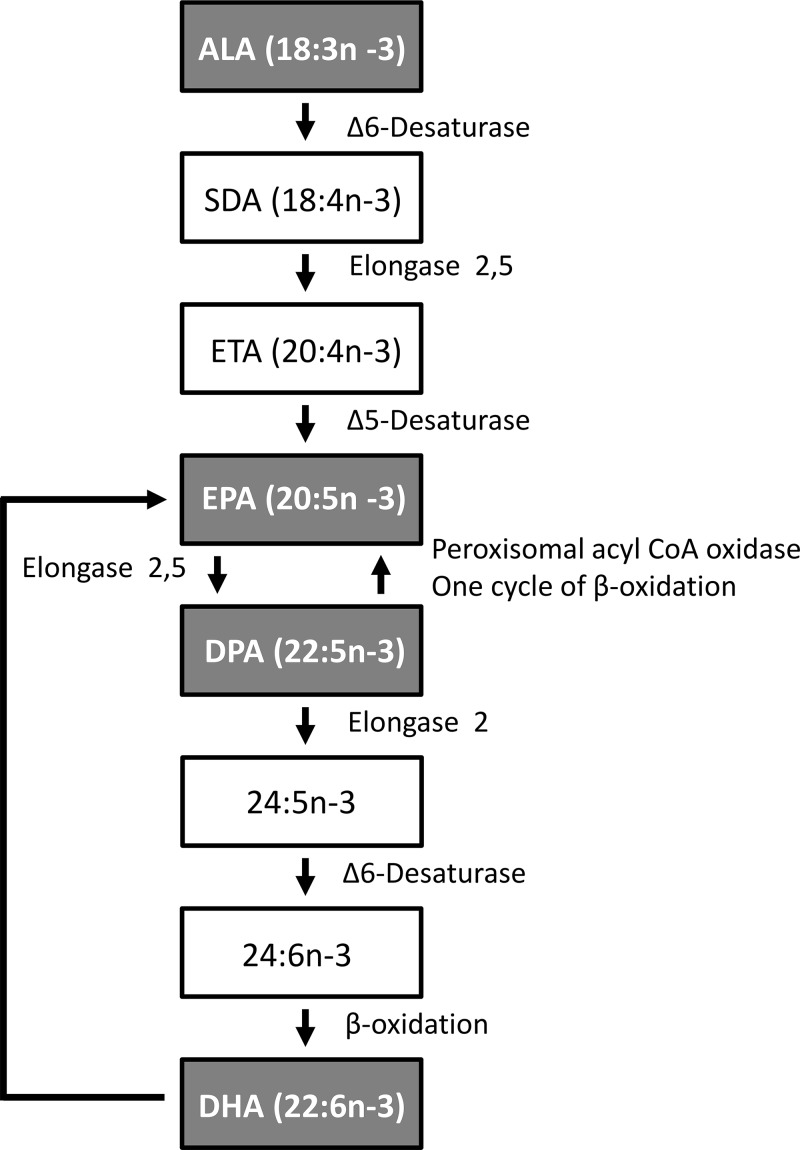

α-Linolenic acid (ALA; 18:3, n-3) is the essential fatty acid precursor to the long-chain (LC) n-3 PUFAs, including eicosapentaenoic (EPA; 20:5, n-3), docosahexanoic (DHA; 22:6, n-3), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA; 22:5, n-3) (Fig. 1). Dietary LC n-3 PUFA ingestion from marine oil consumption contributes to anti-inflammatory properties and cardiovascular, metabolic, and neural health (1–4). The n-6 and -3 PUFAs exert their biologic activities mainly via formation of bioactive lipid mediators, termed eicosanoids and docosanoids (5). For example, arachidonic acid (AA; 20:4, n-6) is the major physiologic precursor to proinflammatory eicosanoids; prostaglandins (PGs; e.g., PGE2), thromboxanes (TXs; e.g., TXB2), and leukotrienes (LTs; e.g., LTB4). Comparatively, the EPA-derived eicosanoids (e.g., PGE3, TXB3, and LTB5) possess less potency, and competition between EPA and AA has long been proposed to contribute to anti-inflammatory LC n-3 PUFA bioactivity (6). More recently, LC n-3 PUFAs were discovered to be precursors to distinct lipid mediators with dual anti-inflammatory and proresolving bioactivity, including the resolvins (Rvs), protectins (PDs), and MaRs, collectively termed specialized proresolving lipid mediators (SPMs) (7, 8).

Figure 1.

Biosynthetic pathway from EPA to DHA via DPA. 24:5, n-3, tetracosapentaenoic acid; 24:6, n-3, tetracosahexaenoic acid.

SPM biosynthesis involves sequential metabolism of n-3 PUFA substrates by multiple cell types that express the required enzymatic machinery in a compartmentalized manner [e.g., neutrophil 5-lipoxygenase (LOX), platelet 12-LOX, and monocyte 15-LOX]. The LOX pathways generate specific positional monohydroperoxy/monohydroxy EPA (HpEPE/HEPE) and DHA [monohydroperoxy DHA (HpDoHE)/monohydroxy DHA (HDoHE)] isomers that may have inherent bioactivity, in addition to functioning as intermediates in transcellular SPM biosynthetic pathways. For example, metabolism of DHA via 15-LOX and 12-LOX pathways generates 17S-HpDoHE and 14S-HpDoHE, key intermediates in the PD (9) and MaR (10, 11) biosynthetic pathways, respectively. Following reduction from 17-HpDoHE, 17-hydroxydocosahexanoic acid (HDoHE) is also a precursor to the d-series resolvins (RvDs) 1–6 (12–15). Similarly, EPA is converted to 18R-hydroxy-EPA (18R-HEPE) by acetylated COX-2 (in the presence of aspirin) (16) or endogenous cytochrome P450 (in the absence of aspirin) (17). 18R-HEPE is a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of the E-series resolvins (RvEs) including RvE1 (5S,12R,18R-TriHEPE) (16, 18, 19), RvE2 (5S,18R-DiHEPE) (20, 21), and RvE3 (17R,18R-DiHEPE) (22–24). LC n-3 PUFAs are also effective substrates for the less well-characterized cytochrome P450 (CYP) epoxygenase pathway (25), and recent reports show that CYP metabolites may also contribute to LC n-3 PUFA bioactivity (26). CYP preferentially targets the n-3 double bond resulting in the formation of 17,18-epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (EpETE) from EPA and 19,20-epoxydocosapentaenoic acid (EpDPE) from DHA (27). Subsequent action of soluble epoxide hydrolase on these epoxides forms the downstream vicinal diols [e.g., 17,18-hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid (DiHETE) from EPA and 19,20-dihydroxy DPA (DiHDoPE) from DHA (28)].

Compared with EPA and DHA, very little is known regarding the metabolic fate and bioactivity of the third intermediary dietary n-3 PUFA DPA (22:5, n-3) (29, 30). n-3 DPA contributes a considerable proportion of the LC n-3 PUFA found in marine sources. For example, n-3 DPA levels in common fish oils vary from 1 to 5% of total fatty acids, in which the total LC n-3 PUFA content (EPA+DPA+DHA) varies from 11 to 27% (31). We have shown that dietary supplementation of humans with pure n-3 DPA or EPA (8 g total over 7 d) had distinct and specific incorporation patterns into plasma lipid fractions and red blood cell phospholipids (32). DPA supplementation increased the levels of both EPA and DHA, in addition to n-3 DPA, in the blood triacylglycerol (TAG) fraction (32). Consistently, DPA supplementation in rats increased liver concentrations of not only n-3 DPA, but also of both DHA and EPA (33). Thus, DPA may act as an LC n-3 PUFA intermediate reservoir contributing to the biosynthesis of both EPA- and DHA-derived bioactive lipid mediators. n-3 DPA itself is also a potential direct substrate for enzymes in the lipid mediator biosynthetic pathways. During inflammation resolution in mice, n-3 DPA is converted to novel docosanoid mediators congenerous to the previously established SPMs derived from DHA (34). These newly identified n-3 DPA docosanoid families termed RvDn-3DPA, PDn-3DPA, and MaRn-3DPA were shown to possess potent anti-inflammatory and proresolving bioactivity similar to the earlier described SPMs derived from EPA and DHA (34). Whether such DPA specific docosanoids are detectable in human biologic fluids/tissue, the potential of dietary PUFA intake to modulate levels of these compounds in vivo, and their physiologic relevance in human physiology and nutrition currently remain unknown.

The purpose of the current study was to characterize the changes in human plasma lipid mediator profile in response to 1 wk of dietary supplementation with either pure n-3 DPA or pure EPA. We hypothesized on the basis of our previous studies (32, 33), that dietary DPA may influence plasma EPA- and DHA-derived bioactive lipid mediators, as well as modulate abundance of novel DPA-specific docosanoids in human plasma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Ten healthy female subjects (age, 25.5 ± 3.3 yr; BMI, 22.3 ± 1.6 kg/m2) were recruited to participate in the study. Participants provided written informed consent and completed a medical questionnaire. Participants were excluded if they were at high risk of any form of cardiovascular disease (based on family history), or were overweight (≥26 kg/m2). Ethics approval was obtained from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (EC2011-023).

Subject habitual PUFA intake

All participants completed a PUFA Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) during screening to determine habitual dietary PUFA intake and study eligibility. Subjects were excluded from participation if they consumed more than 500 mg of LC n-3 PUFA per day [based on results of the PUFA FFQ (35–37)]. The habitual dietary intake of the subjects deemed eligible for the study was found to be 102 ± 66 mg of LC n-3 PUFA/d. Participants were also requested to refrain from consuming high LC n-3 PUFA products during the study, including fish, red meat, and LC n-3 PUFA-fortified products (2 marine or 2 red meat meals per week and 2 LC n-3 PUFA-fortified products/wk). Finally, the participants were asked to provide a recall of their diet 24 h before blood sampling. As previously reported, it was found that the participants did not consume any fish during the study period, and consumption of red meat was ≤2 servings per week (32).

DPA and EPA supplements

Purified EPA (Maxomega EPA 98 FFA, 99.8% PUFA containing ≥98% EPA; w/w) and n-3 DPA (Maxomega DPA 97 FFA: 99.8% PUFA containing ≥97% n-3 DPA; w/w) oils, both as free fatty acids, were sourced from Equateq, Ltd. (Breasclete, United Kingdom). The fatty acid profiles of the oils (area% FAMES) were tested and approved by the manufacturer and met company release specifications of ≥97% pure n-3 DPA (22:5, n-3) for Maxomega DPA 97 FFA and ≥98% pure n-3 EPA (20:5 n-3) for Maxomega EPA 98 FFA. All supplements were used within 1 year of the date of manufacture before the indicated expiration date. For dietary supplementation trials the LC n-3 PUFA oils were diluted 1:1 in olive oil (OO). Pure OO alone in the absence of LC n-3 PUFA served as the control supplement.

Study design

This study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which each subject received each of 3 dietary supplements (OO, n-3 EPA or n-3 DPA) in a crossover manner. All participants received the OO placebo supplement on their first visit and were then randomized to receive either the DPA or EPA supplement on the subsequent 2 visits. Each supplementation period lasted 7 d, and a 2 wk washout period was included between each trial before crossover administration of the next intervention.

The night before each of the 3 experimental supplementation trials, participants were provided with a standardized meal (200 g dry pasta and 70 g tomato sauce). The subjects arrived at the laboratory the following morning in a fasted state, and a resting venous blood sample was drawn (d 0). They were provided with a meal consisting of 180 g of instant mashed potato (Continental Deb; Unilever Australasia, Sydney, NSW, Australia) containing: the placebo (20 ml OO), 2 g of purified EPA mixed with 18 ml of OO, or 2 g of purified DPA mixed with 18 ml of OO. The participants were required to consume each of these breakfasts in 15 min. They were then provided with six 2-g aliquots of a 1:1 mixture of either 1 g purified n-3 DPA or 1 g purified n-3 EPA mixed with 1 g OO. During the placebo period, the participants received six 2-g aliquots containing OO alone as a placebo. The oils were packaged in individual 2-ml cryovials within an opaque box (to protect the oils from exposure to light). The participants were instructed to keep the supplements in a refrigerator at 4°C and to consume a single 2-g dose of the oil with 200 ml of standard commercial orange juice each morning for the following 6 d. The dose of DPA and EPA administered was thus 2 g on the first day followed by a dose of 1 g/d for 6 additional days (8 g total/wk). Although evidence of the tolerable upper intake of DPA in isolation is lacking, supplemental intakes of DHA or EPA alone up to ∼1 g/d do not appear raise safety concerns for the general population (30). On the morning of d 7, participants attended the clinical facility following an overnight fast to provide a post-supplementation period fasting blood sample. Participants received daily reminders to consume their supplement and were asked to return the vials after consuming the supplements, to monitor compliance.

Sample preparation and liquid chromatography–mass spectometry analysis of lipid mediators

Fasting venous blood samples on d 0 and 7 of each of the 3 dietary supplementation trials were collected into EDTA-coated Vacutainers (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and were immediately centrifuged for 15 min at 591 g at 15°C. The plasma was immediately collected from the red blood cell pellet and stored in aliquots at −80°C until further analysis (<1 yr storage). Aliquots of plasma samples (100 µl) were thawed once, spiked with 5 ng each of PG E1-d4 (PGE1-d4), leukotriene B4-d4 (LTB4-d4), and 15(S)-HETE-d8 as internal standards for analyte recovery and quantitation and mixed thoroughly. The samples were then extracted for fatty acyl lipid metabolites with C18 extraction columns, as described earlier with minor modifications (38, 39). In brief, the internal standard spiked samples were applied to conditioned C18 cartridges, washed with 15% methanol in water followed by hexane, and dried in a vacuum. The cartridges were eluted with 0.5 ml methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. The eluate was dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 50 µl methanol-25 mM aqueous ammonium acetate (1:1) and subjected to liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) analysis.

HPLC was performed on a Prominence XR system (Shimadzu, Somerset, NJ, USA) equipped with a Luna C18 (3 µm, 2.1 × 150 mm) column. The mobile phase consisted of a gradient between A: methanol-water-acetonitrile (10:85:5 v/v) and B methanol-water-acetonitrile (90:5:5 v/v), both containing 0.1% ammonium acetate. The gradient program with respect to the composition of B was as follows: 0–1 min, 50%; 1–8 min, 50–80%; 8–15 min, 80–95%; and 15–17 min, 95%. The flow rate was 0.2 ml/min. The HPLC eluate was directly introduced to the ESI source of QTrap5500 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, Singapore) in the negative ion mode with following conditions: curtain gas: 35 psi, GS1: 35 psi, GS2: 65 psi; temperature: 600°C, ion spray voltage: −1500 V; collision gas: low; declustering potential, −60 V, and entrance potential, −7 V. The eluate was monitored by multireaction monitoring (MRM) method to detect unique molecular ion–daughter ion combinations for each of 125 transitions (to monitor a total of 144 lipid mediators and 3 internal standards) with 8 ms dwell time for each transition. Optimized collisional energies (18–35 eV) and collision cell exit potentials (7–10 V) were used for each MRM transition. The data were collected with Analyst 1.6 software and the MRM transition chromatograms were quantitated by MultiQuant software (both from AB Sciex). The internal standard signals in each chromatogram were used for normalization for recovery as well as relative quantitation of each analyte [PGE1-d4 for prostaglandins, LTB4-d4 for di- and trihydroxy fatty acids, and 15(S)-HETE-d8 for monohydroxy and epoxy fatty acids]. All lipid mediators quantified were positively identified by comparing HPLC retention times with authentic standards (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and specific parent–daughter ion combinations as well as mass spectra obtained from information dependent acquisition (IDA) method.

Detection and quantitation limits (expressed as picograms injected into the column) of the method for each class of lipid mediators were determined by injecting serial dilutions of representative standards, and relative response ratios of analytes to internal standards were determined, as described before (38). Minimum signal–noise ratios used for detection and quantitation were 3 and 5, respectively. The detection and quantitation limits, respectively, were 2 and 10 pg for monohydroxy fatty acids (e.g., HETEs), 1 and 10 pg for dihydroxy fatty acids (e.g., LTB4), 1 and 8 pg for trihydroxy fatty acids (e.g., RvD1), and 8 and 25 pg for PGs (e.g., PGE1).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot 12.0. Data were analyzed using 2-way ANOVA with both supplement (OO vs. EPA vs. DPA) and time (d 0 vs. 7) as within-subject effects. When main or interactive effects were observed, pair-wise comparisons were made with Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc test. Results are presented as means ± sem. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of DPA (22:5, n-3) supplementation on plasma n-3 PUFA lipid mediators

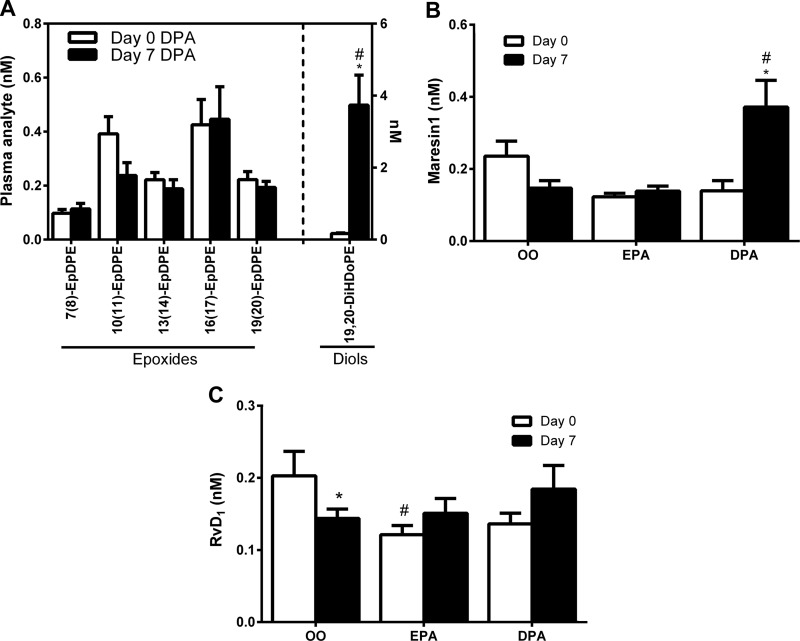

DHA metabolites

DPA supplementation increased plasma levels of the DHA metabolite 13-HDoHE (1.9-fold) (Supplemental Table 1), but did not influence any other monohydroxy-DHA regioisomers or DHA epoxides (EpDPEs) (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Table 1). Nevertheless, the DHA epoxide vicinal diol metabolite 19,20-DiHDoPE was markedly elevated (22-fold) after DPA supplementation (Fig. 2A). Peaks corresponding to several di- and trihydroxylated DHA mediators (the d-series SPMs) were detected, including RvD1 (7S,8R,17S-TriHDoHE), RvD2 (7S,16R,17S-TriHDoHE), RvD6 (4S,17S-DiHDoHE), MaR1 (7R,14S-DiHDoHE), and PD1 isomer 10S,17S-DiHDoHE (PDX) (Supplemental Table 1). Basal plasma levels of DHA SPMs were low and generally around the quantitative limits (≤LOQ) of the assay used. Plasma MaR1 was significantly elevated (∼3 fold), to within the quantifiable range (∼150 pg/ml) after 7 d of DPA supplementation (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, plasma RvD1 decreased from d 0 to 7 of the placebo OO supplementation trial (Fig. 2C); a response not observed in either the EPA or DPA trials. Transitions corresponding to PD1 and RvD5 were monitored, but peaks corresponding to these analytes were not detectable in most of the samples. Other detected DHA SPMs were not influenced by DPA supplementation (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 2.

Plasma DHA metabolites influenced by DPA supplementation. A) Plasma concentration of CYP-pathway–derived DHA epoxides (EpDPE) and downstream vicinal diols (DiHDoPE) in response to DPA supplementation. B) Plasma concentration of MaR1 in response to supplementation with OO, EPA, or DPA. C) Plasma concentrations of RvD1 in response to supplementation with OO, EPA, or DPA. Value are means ± sem. *P < 0.05 vs. d 0 within respective supplementation period; #P < 0.05 vs. placebo OO supplementation at the same time point.

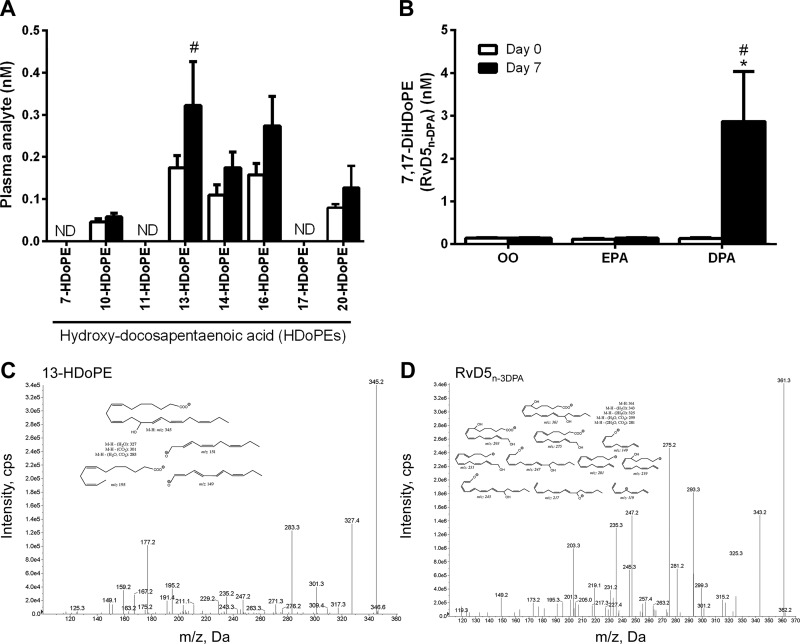

DPA metabolites

In addition to known DHA-derived lipid mediators, we detected several related metabolites of n-3 DPA itself in human plasma. These included monohydroxy DPA (HDoPE) and dihydroxy DPA (DiHDoPE) products (Fig. 3). Of these, 13-, 14-, 16-, and 20-HDoPE (but not 7-, 10-, 11-, or 17-HDoPE) were present at detectable concentrations (Fig. 3A). Among the monohydroxylated DPA products detected, only 13-HDoPE was significantly influenced by dietary DPA supplementation (mass spectrum in Fig. 3C). We also identified a dihydroxylated n-3 DPA mediator 7,17-dihydroxy-DPA (7,17-DiHDoPE) in human plasma (mass spectrum in Fig. 3D). After DPA supplementation there was a robust increase (∼20-fold) in plasma levels of 7,17-DiHDoPE (Fig. 3B). Notably, 7,17-DiHDoPE is a structural analog of the 17-dihydroxy-DHA SPM RvD5, which Dalli et al. (34) recently termed RvD5n-3DPA following its discovery and elucidation in mice and cultured human neutrophils/macrophages.

Figure 3.

Plasma n-3 DPA metabolites influenced by DPA supplementation. A) HDoPE metabolites in human plasma in response to dietary DPA supplementation. B) Plasma concentrations of 7,17-DiHDoPE (RvD5n-3DPA) in response to supplementation with OO, EPA, or DPA. C, D) Representative tandem mass spectra and fragment assignments (insets) used for the identification of 13HDoPE (C) and 7,17-DiHDoPE (or RvD5n-3DPA) (D). The mass spectra shown are for a representative plasma sample obtained on d 7 of the n-3 DPA supplementation trial. Value are means ± sem. *P < 0.05 vs. d 0 within respective supplementation period; #P < 0.05 vs. placebo OO supplementation at the same time point.

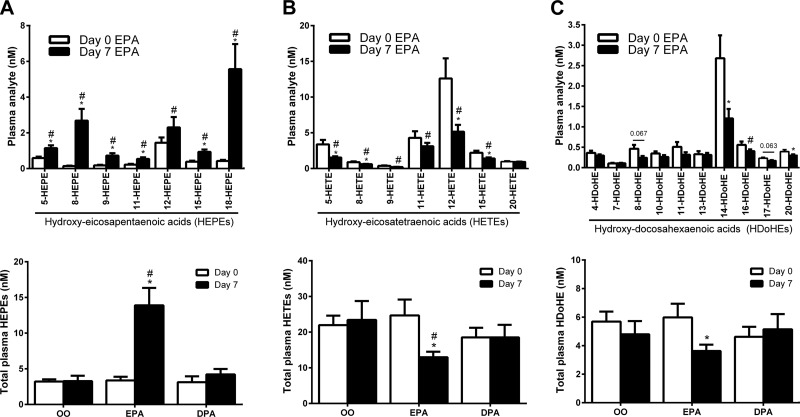

EPA metabolites

EPA metabolites detected in human plasma included numerous monohydroxy-EPA regioisomers (HEPEs), EPA epoxides/vicinal diols (e.g., EpETEs/DiHETEs), and series-3 PGs (e.g., PGD3) (Supplemental Table 1). Peaks corresponding to di- and trihydroxylated EPA mediators (e.g., LTB5, LXA5, and RvE1) were also observed but were generally ≤LOQ of the assay used in most of the samples. Of the numerous EPA metabolites detected in human plasma, none was significantly influenced by DPA supplementation.

Effect of DPA (22:5, n-3) supplementation on plasma n-6 PUFA lipid mediators

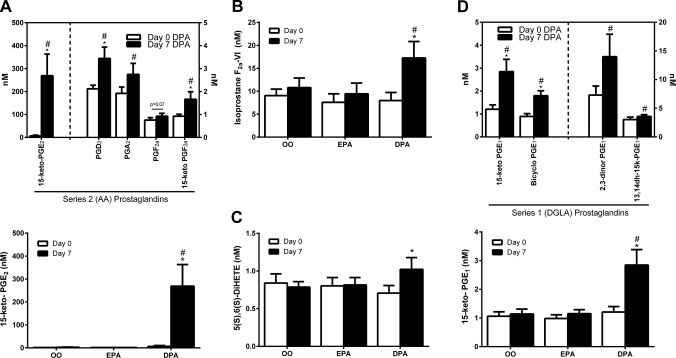

AA (20:4, n6) metabolites

We found unexpectedly that plasma concentrations of several AA-derived PGs and their downstream degradation products were increased by n-3 DPA supplementation (Fig. 4A). Most notably, 15-keto-PGE2 (a PG 15-hydroxy dehydrogenase metabolite of PGE2) was markedly elevated (∼40-fold) in the DPA trial (Fig. 4A). This response was also evident, albeit to a lesser extent, for PGA2, PGD2, PGF2α, and the downstream circulating PG metabolites 15-keto-PGF2α, and bicyclo-PGE2 (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the AA-derived isoprostane F2α-VI (Fig. 4B) and 5S,6S-DiHETE (Fig. 4C), a nonenzymatic hydrolysis product of leukotriene A4 (LTA4) were similarly found to be elevated only after DPA supplementation. Plasma TXB2 and PGE2 themselves were not influenced by DPA supplementation (Supplemental Table 1).

Figure 4.

Plasma n-6 PUFA metabolites influenced by n-3 DPA supplementation. A) Plasma concentrations of AA (20:4, n-6)-derived (series 2) PGs in response to 7-d DPA supplementation. B) Plasma isoprostane F2aVI levels in response to 7 d supplementation with OO, EPA, or DPA. C) Plasma levels of 5(S),6(S)-DiHETE, a nonenzymatic degradation product of LTA4 in response to 7 d supplementation with OO, EPA, or DPA. D) Plasma concentrations of DGLA (20:3, n-6)-derived (series 1) PGs in response to 7 d DPA supplementation. Value are means ± sem. *P < 0.05 vs. d 0 within the respective supplementation period; #P < 0.05 vs. placebo OO supplementation at the same time point.

Dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (20:3, n6) metabolites

Plasma PG metabolites of dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA, 20:3, n-6) including 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE1 (13,14dh-15k-PGE1), bicyclo-PGE1, 2,3-dinor PGE1, were also significantly increased after the n-3 DPA supplementation trial (Fig. 4D).

Effect of EPA (20:5, n-3) supplementation on plasma PUFA lipid mediators

EPA metabolites

Unlike DPA, EPA supplementation increased plasma levels of the monohydroxylated EPA (HEPE) metabolites (see Fig. 5A). Most notably, 8-HEPE (20-fold) and the RvE series precursor 18-HEPE (13-fold) were markedly increased by EPA supplementation. The EPA-derived CYP pathway epoxide 11,12-epoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (11,12-EpETE; but not related to 8,9-, 14,15-, or 17,18-EpETE regioisomers) was also increased (∼3-fold) by EPA supplementation (Supplemental Table 1). Plasma RvE1 concentrations were generally ≤LOQ of our assay, but qualitatively corresponded to ∼150 pM (∼50 pg/ml). RvE1 remained ≤LOQ after EPA supplementation, despite marked increases in the abundance of the RvE precursor 18-HEPE.

Figure 5.

Plasma PUFA metabolites influenced by EPA supplementation. A) HEPE metabolites in human plasma in response to EPA supplementation. B) HETE metabolites in human plasma in response to EPA supplementation. C) HDoHE metabolites in human plasma in response to EPA supplementation. Value and means ± sem *P < 0.05 vs. d 0 within the respective supplementation period; #P < 0.05 vs. placebo OO supplementation at the same time point.

AA metabolites

EPA supplementation reduced numerous plasma monohydroxylated metabolites of AA (HETEs; Fig. 5B). 5-HETE (−55%) and 12-HETE (−60%), enzymatic products of 5-LOX and 12-LOX, respectively, were most notably suppressed. In contrast, 20-HETE, a CYP (γ-hydroxylase pathway) metabolite of AA was not influenced by EPA supplementation. CYP pathway AA epoxides including 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-epoxy-eicosatrienoic acid (EpETrE) were also unaffected, whereas select downstream vicinal diols 5,6-, 8,9-dihydroxy-eicosatrienoic acid (DiHETrE) were significantly reduced (Supplemental Table 1). Further notable changes in n-6 PUFA lipid mediator profile in response to EPA supplementation included a decrease in the PGE2 metabolite, tetranor-PGEM (−70%) and an increase (2.7-fold) in the PGD2 metabolite, 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGD2.

DHA metabolites

Several hydroxy-DHA species were found to be suppressed in human plasma after EPA supplementation (Fig. 5C). Most notably, 14-HDoHE, the most abundant hydroxy-DHA derivative detected in human plasma and a key activation marker of the MaR biosynthesis pathway was reduced by 55% after the EPA trial. 17-HDoHE a key intermediate in the biosynthesis of d-series resolvins also tended to be more modestly reduced by EPA (−26%; P = 0.063). DHA metabolites of CYP epoxygenase including 10,11- and 13,14-epoxy-docosapentaenoic acid (EpDPE) were also decreased (Supplemental Table 1). Despite these changes in several primary DHA metabolites, raw DHA-derived SPMs themselves were not influenced by EPA supplementation.

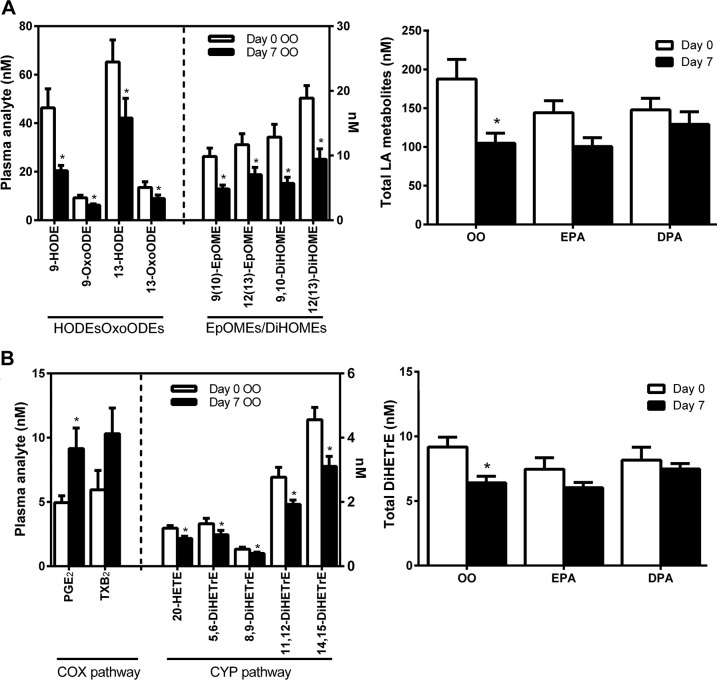

Effect of OO placebo on plasma lipid mediators

We found that a specific subset of lipid mediators was significantly influenced by our OO placebo condition (Fig. 6). These analytes included metabolites of linoleic acid (LA) (18:2, n-6) encompassing both hydroxy-/oxo-octadecadienoic acids (9-HODE/9-OxoODE, 13-HODE/13-OxoODE) and epoxy-/dihydroxy-octadecanoic acids [9(10)EpOME/9(10)DiHOME, 12(13)EpOME/12(13)DiHOME], all of which decreased by ∼30–60% from d 0 to 7 of the initial OO trial (Fig. 6A). Similarly, plasma monohydroxylated metabolites of ALA (18:3, n-3) [9(S)-HOTrE and 9-OxoOTrE], dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA) (20:3, n-6) [8(S)-HETrE] and Mead acid (20:3, n-9) [5(S)-HETrE] were reduced in response to OO supplementation (Supplemental Table 1). A subset of AA metabolites derived from the CYP pathway (both epoxygenase and γ-hydroxylase) also appeared to be influenced by the OO placebo (Fig. 6B). These analytes included the AA vicinal diols 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-DiHETrE (epoxygenase pathway), as well as 20-hydroxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) γ-hydroxylase pathway, all of which were decreased from d 0 to 7 of the OO supplementation trial.

Figure 6.

Plasma PUFA metabolites influenced by placebo (OO) supplementation. A) LA (18:2, n-6) derived HODEs/oxo-octadecadienoic acids (OxoODEs) and epoxy-octadecenoic acids (EpOMEs)/ DiHOMEs). B) AA (20:4, n-6) derived COX-1 and 2 pathway prostanoids (PGE2 and TXB2) and CYP-pathway–derived epoxide vicinal diols (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-DiHETrE). Value are means ± sem. *P < 0.05 vs. d 0 within the respective supplementation period.

Similar patterns of a reduction in these OO-sensitive metabolites of LA (HODEs/OxoODE, EpOMEs/DiHOME), ALA [9(S)-HOTrE/9-OxoOTrE], DGLA [8(S)-HETrE], Mead acid [5(S)-HETrE], and AA (DiHETrE regioisomers) were generally observed in response to the subsequent EPA and DPA supplementation trials (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Table 1). However, as n-3 PUFA supplements were administered as 1:1 mixtures of OO:EPA or :DPA, these changes cannot be true effects of EPA or DPA supplementation and were likely a direct result of the OO component.

DISCUSSION

A considerable amount of research has focused on the potential roles of EPA and DHA in the beneficial effects of marine oils. In contrast, the third intermediary LC-n-3 PUFA DPA has rarely been investigated. Limited studies on n-3 DPA have reported effects on platelet aggregation (40, 41), modulation of endothelial cell function (42, 43), inhibition of tumor growth (44), reduction in liver lipogenic gene expression (45), lowering of circulating lipids (46–48), and improvements in age-associated cognitive decline (49). Although interconversion of EPA, DPA, and DHA via retroconversion and elongation pathways may occur (Fig. 1), important differences appear evident in the bioactivity of individual LC n-3 PUFAs. After short-term supplementation in humans, pure n-3 DPA and EPA possess specific incorporation patterns into plasma and red blood cell lipids (32). In comparison to the other LC n-3 PUFAs, DPA is also more effective in inhibiting platelet aggregation (40), stimulating endothelial cell migration (42), and has more potent antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects on cancer cells (44). Associations between higher blood DPA levels and reduced human cardiovascular disease risk further suggest beneficial properties of this little-studied dietary fatty acid that are distinct from other LC n-3 PUFAs (50–53). Despite these observations, the metabolic fate and mechanisms of action of n-3 DPA have remained poorly understood.

Dietary supplementation with fish oils containing a mixture of LC n-3 PUFAs have generally showed increases in circulating DHA metabolites (54–59). However, many previous human PUFA supplementation studies have either not included the d-series SPMs themselves in their analysis (56–58, 60), or were unable to detect them (54, 61–64). Nevertheless, recent studies have detected d-series resolvins in human blood (55, 59, 65–68), and plasma RvD1 concentrations have been reported to be increased after fish oil supplementation in 2 recent studies (55, 59). In the present study, we detected several DHA-derived SPMs at low pictogram permilliliter concentrations in human plasma, including RvD1, RvD2, RvD6, MaR1, and 10S,17S-DiHDoHE (PD1 isomer or PDX). On the other hand, PD1 itself and RvD5 were not detected. Both RvD1 and MaR-1 were found to be modestly increased after the n-3 DPA supplementation trial. Furthermore, the DHA vicinal diol 19,20-DiHDoPE was markedly increased by DPA supplementation. Unlike DPA, supplementation with pure EPA actually decreased several plasma DHA metabolites, most notably the MaR pathway intermediate 14-HDoHE. The collective data suggest that one important metabolic fate of dietary n-3 DPA is a contribution to biosynthesis of DHA-derived docosanoids. In contrast, dietary EPA has no substantial contribution to docosanoid biosynthesis in healthy humans and EPA supplementation in isolation has opposing modulatory effect on d-series SPM pathway intermediates, likely via competition with endogenous DHA as the substrate.

In addition to established DHA docosanoids, we detected several specific metabolites of n-3 DPA itself in human plasma, including HDoPE isomers and the dihydroxylated DPA metabolite 7,17-DiHDoPE (RvD5n-3DPA). In the absence of supplemental n-3 PUFA intake, circulating levels of DPA-derived monohydroxy fatty acids were generally lower (20–60 pg/ml) when compared to levels of monohydroxylated EPA and DHA products (100–300 pg/ml) (Supplemental Table 1). However, plasma concentrations of the dihydroxylated n-3 DPA metabolite RvD5n-3DPA were similar to that of SPMs derived from EPA (e.g., RvE1) and DHA (e.g., MaR1; ∼50 pg/ml). RvD5n-3 DPA is a recently discovered n-3 DPA analog of the 17-dihydroxy-DHA-derived SPM RvD5 which was shown to possess potent anti-inflammatory/proresolving bioactivity (34). In our study, RvD5n-3DPA was detected at low picogram/milliliter concentrations (∼50 pg/ml) in basal plasma, but was markedly elevated (≥20 fold) to concentrations of ≥1 ng/ml after DPA supplementation. Although RvD5n-3DPA has been shown to be produced in vitro by human neutrophils and macrophages, to our knowledge, this is the first report of the detection and modulation of n-3 DPA series resolvins in human blood in vivo. Unlike DPA, supplementation with pure EPA had no effect on plasma levels of RvD5n-3DPA or the DPA content of plasma lipids [previously reported in Miller et al. (32)], at least in the timeframe of a week, and ingestion of DPA substrate itself is needed to modulate circulating levels of DPA docosanoids. The biologic fate of dietary DPA to form unique lipid mediators with anti-inflammatory and proresolving properties, and lack of redundancy by EPA, provides a novel mechanism that may explain bioactivity of n-3 DPA independent of other LC n-3 PUFAs.

In our previous report, we found that in these same subjects n-3 DPA supplementation increased the proportion of EPA as well as DPA in blood TAG fraction, suggesting that dietary DPA may undergo some degree of retroconversion to EPA in humans (32) (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, DPA supplementation failed to influence any of the numerous detected plasma EPA metabolites here, suggesting that the metabolic fate of dietary DPA and EPA are highly distinct. Supplementation with pure EPA was, on the other hand, highly effective in elevating plasma levels of numerous EPA metabolites. Of particular interest, the e-series resolvin precursor 18-HEPE was markedly increased by EPA supplementation (∼13-fold). We detected RvE1 itself in basal plasma at concentrations of ∼150 pM (∼50 pg/ml), but despite the marked increases in plasma concentrations of the RvE precursor 18-HEPE, RvE1 levels were unaffected. A number of recent studies have reported elevated plasma 18-HEPE in human subjects consuming fish oil (54, 59, 66), and RvE1 has been measured in human blood at comparable concentrations to that reported here, ranging between ∼10–200 pg/ml (19, 65, 66, 68). Barden et al. (66) also found that fish oil supplementation could increase plasma levels of RvE1 in healthy human volunteers. On the other hand, others have questioned the relevance of circulating RvEs in humans consuming fish oil supplements (55, 58, 62, 63, 69). The reason for these discrepancies between studies remains unclear, but may relate in part to analyte stability, sample handling, and methodological and analytical differences (65).

A notable finding of the current study is that several additional metabolites of EPA, the in vivo enzymatic biosynthesis of which is not well characterized, were markedly elevated with EPA supplementation. For example, 8-HEPE was one of the most responsive analytes to EPA feeding, a finding that is consistent with several studies in which human subjects were fed fish oil (57, 60, 70). Although the physiologic significance of these analytes in human blood remains to be determined, 8-HEPE and 9-HEPE in krill extracts possess potent bioactivity as PPAR agonists, inducing metabolic responses including stimulation of fatty acid oxidation, adipogenesis, and glucose uptake in vitro (71).

We were surprised to find that some n-6 PUFA metabolites were elevated in the plasma of subjects receiving n-3 DPA supplementation. Most notably, 15-keto-PGE2 was markedly increased (≥40-fold) to concentrations of ∼250 nM (∼100 ng/ml). 15-keto-PGE2 is generally known as an inactive metabolite of PGE2 produced via the PG 15-hydroxy dehydrogenase pathway. Therefore, an increase in 15-keto-PGE2/PGE2 ratio could be seen to be indicative that DPA clears active PGE2 from circulation and thus tones down inflammatory events. However, total PGE2 levels (sum of PGE2, 15-keto-PGE2, 13,14-dihydro-15-keto-PGE2, and bicyclo-PGE2) were also markedly elevated after DPA supplementation. Other AA- and DGLA-derived PG species were found to be more modestly increased by DPA. Although the conversion of PGE2 to 15-keto-PGE2 has been classically viewed as an inactivating step, recent studies have suggested that 15-keto-PGE2 possesses activity distinct from PGE2. For example, it was recently reported that 15-keto-PGE2, serves as an endogenous PPARγ ligand, inducing potential beneficial physiologic effects (72–73). The mechanism by which n-3 DPA may modulate n-6 PUFA metabolite profile in human blood and the physiologic ramifications of this apparent effect currently remain unclear.

We found that supplementation with pure EPA reduced plasma levels of the AA-derived LOX pathway products 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting reduced hydroxy- and epoxy-AA metabolites in humans receiving fish oil (54–58, 60). DPA, however, had no effect on plasma hydroxy- and epoxy-AA metabolites, further confirming the divergent activity of EPA and DPA. Few previous studies have reported the effect of dietary PUFAs on metabolites of the COX pathways, probably because of the instability of some of these analytes during the sample saponification used in many studies to liberate esterified oxylipins (54, 55, 58, 60). We found that EPA supplementation elevated plasma levels of EPA-derived LTB5, but had little or no influence on any of the detected AA-derived PGs (e.g., PGE2) or LTs (e.g., LTB4). Fish oil supplementation has also been reported to increase PGE3 and LTB5 (54), but has little if any effect on AA eicosanoids (54, 56, 58). One exception in the current study was 13,14dh-15k-PGD2, a downstream plasma metabolite of PGD2, which was elevated after EPA supplementation (2.6-fold). Notably, PGD2 and its downstream metabolic products have been posited to possess anti-inflammatory properties and may thus potentially contribute to the bioactivity of EPA.

Although this study involved a small number of subjects, one of its strengths was that participants were of a single gender and of a similar age and body mass index. This is supported by a recent review which indicated that because women and men have different proportions of DHA in blood and tissues and because they convert ALA to DHA at different rates, single gender studies should be conducted (74). An unexpected finding was that the OO, used as a placebo control here, was found to significantly influence a specific subset of lipid mediators. The OO used was specifically chosen, because it was highly refined and presumed to contain low levels of phytochemicals. As the n-3 DPA and EPA were administered in OO, we cannot, however, rule out that the OO in combination with the n-3 fatty acids had additive effects or indeed interactive effects. On this basis, future studies may include “no oil” as an additional control treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

Dietary supplementation with EPA and DPA had highly divergent modulatory effects on the human plasma bioactive lipid mediator profile. DPA supplementation primarily increased levels of DPA-specific docosanoids with apparent secondary effects to elevate select n-3 DHA and n-6 PUFA metabolites. In contrast, EPA supplementation increased circulating levels of numerous LC n-3 PUFA eicosanoids, but had little or no effect on plasma docosanoid concentrations. These data show that the metabolic fates of dietary DPA and EPA are highly specific and that these distinct LC n-3 PUFA have nonredundant physiologic effects in humans in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Marissa Caldow (University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) for assistance with the clinical trial, Mr. Senlin Zhou (Lipidomics Core Facility, Wayne State University) for assistance in sample preparation for LC–MS analyses, and the study participants. The study was supported in part by funding received from the Food and Health Program (University of Auckland), Meat and Livestock Australia, the Strategic Research Centre for Molecular Medicine (Deakin University). Equateq, Ltd. (Breasclete, United Kingdom) generously provided the pure supplements and the National Center for Research Resources, U.S. National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources Grant S10RR027926 (to K.R.M.). The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CYP

cytochrome p450

- DHA

docosahexanoic acid

- DiHETE

hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- DiHETre

dihydroxyeicsatrienoic acid

- DiHOME

dihydroxy-octadecenoic acid

- DiHoPE

dihydroxy DPA

- DPA

docosapentanoic acid

- EPA

5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z-eicosapentanoic acid

- EpDPE

epoxydocosapentaenoic acid

- EpETE

epoxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- EpOME

epoxyoctadecenoic acid

- HDoHE

monohydroxy DHA

- HDoPE

monohydroxy DPA

- HEPE

hydroxy-eicosapentaenoic acid

- HODE

hydroxyoctadecadienoic acid

- HpDoHE

monohydroperoxy DHA

- LC

long chain

- LC–MS

liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- LT

leukotriene

- MaR

maresin

- MRM

multireaction monitoring

- OO

olive oil

- PD

protectin

- PG

prostaglandin

- Rv

resolvin

- RvD

d-series resolvin

- RvE

e-series resolvin

- SPM

specialized proresolving mediator

- TAG

triacylglycerol

- TX

thromboxane

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A. J. Sinclair, D.Cameron-Smith, G. Kaur, A. E. Larson, and E. G. Miller conceived and designed the study; J. F. Markworth, G. Kaur, E. G. Miller, A. E. Larson, and K. R. Maddipati collected and analyzed the data; J. F. Markworth, D. C. Sinclair, K. R. Maddipati, G. Kaur interpreted the data; J. F. Markworth, K. R. Maddipati, G. Kaur, A. J. Sinclair, and D. Cameron-Smith drafted the manuscript; and all authors helped to revise and approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flachs P., Rossmeisl M Kopecky J.. 2014. The effect of n-3 fatty acids on glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity. Physiol. Res. 63(Suppl 1):S93–S118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerber P. A., Gouni-Berthold I., Berneis K. (2013) Omega-3 fatty acids: role in metabolism and cardiovascular disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 19, 3074–3093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Janssen C. I. F., Kiliaan A. J. (2014) Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) from genesis to senescence: the influence of LCPUFA on neural development, aging, and neurodegeneration. Prog. Lipid Res. 53, 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lorente-Cebrián S., Costa A. G. V., Navas-Carretero S., Zabala M., Martínez J. A., Moreno-Aliaga M. J. (2013) Role of omega-3 fatty acids in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases: a review of the evidence. J. Physiol. Biochem. 69, 633–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stables M. J., Gilroy D. W. (2011) Old and new generation lipid mediators in acute inflammation and resolution. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmitz G., Ecker J. (2008) The opposing effects of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Prog. Lipid Res. 47, 147–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bannenberg G. L., Chiang N., Ariel A., Arita M., Tjonahen E., Gotlinger K. H., Hong S., Serhan C. N. (2005) Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J. Immunol. 174, 4345–4355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serhan C. N. (2014) Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 510, 92–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee P. K., Marcheselli V. L., Serhan C. N., Bazan N. G. (2004) Neuroprotectin D1: a docosahexaenoic acid-derived docosatriene protects human retinal pigment epithelial cells from oxidative stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 8491–8496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serhan C. N., Yang R., Martinod K., Kasuga K., Pillai P. S., Porter T. F., Oh S. F., Spite M. (2009) Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J. Exp. Med. 206, 15–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu Y., Tian H., Hong S. (2010) Novel 14,21-dihydroxy-docosahexaenoic acids: structures, formation pathways, and enhancement of wound healing. J. Lipid Res. 51, 923–932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong S., Gronert K., Devchand P. R., Moussignac R.-L., Serhan C. N. (2003) Novel docosatrienes and 17S-resolvins generated from docosahexaenoic acid in murine brain, human blood, and glial cells: autacoids in anti-inflammation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 14677–14687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcheselli V. L., Hong S., Lukiw W. J., Tian X. H., Gronert K., Musto A., Hardy M., Gimenez J. M., Chiang N., Serhan C. N., Bazan N. G. (2003) Novel docosanoids inhibit brain ischemia-reperfusion-mediated leukocyte infiltration and pro-inflammatory gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43807–43817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serhan C. N., Hong S., Gronert K., Colgan S. P., Devchand P. R., Mirick G., Moussignac R.-L. (2002) Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J. Exp. Med. 196, 1025–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Serhan C. N., Gotlinger K., Hong S., Arita M. (2004) Resolvins, docosatrienes, and neuroprotectins, novel omega-3-derived mediators, and their aspirin-triggered endogenous epimers: an overview of their protective roles in catabasis. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 73, 155–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Serhan C. N., Clish C. B., Brannon J., Colgan S. P., Chiang N., Gronert K. (2000) Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1197–1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arita M., Clish C. B., Serhan C. N. (2005) The contributions of aspirin and microbial oxygenase to the biosynthesis of anti-inflammatory resolvins: novel oxygenase products from omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oh S. F., Pillai P. S., Recchiuti A., Yang R., Serhan C. N. (2011) Pro-resolving actions and stereoselective biosynthesis of 18S E-series resolvins in human leukocytes and murine inflammation. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 569–581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arita M., Bianchini F., Aliberti J., Sher A., Chiang N., Hong S., Yang R., Petasis N. A., Serhan C. N. (2005) Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J. Exp. Med. 201, 713–722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjonahen E., Oh S. F., Siegelman J., Elangovan S., Percarpio K. B., Hong S., Arita M., Serhan C. N. (2006) Resolvin E2: identification and anti-inflammatory actions: pivotal role of human 5-lipoxygenase in resolvin E series biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 13, 1193–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh S. F., Dona M., Fredman G., Krishnamoorthy S., Irimia D., Serhan C. N.. 2012. Resolvin E2 formation and impact in inflammation resolution. J. Immunol. 188, 4527–4534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isobe Y., Arita M., Iwamoto R., Urabe D., Todoroki H., Masuda K., Inoue M., Arai H. (2013) Stereochemical assignment and anti-inflammatory properties of the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E3. J. Biochem. 153, 355–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Isobe Y., Arita M., Matsueda S., Iwamoto R., Fujihara T., Nakanishi H., Taguchi R., Masuda K., Sasaki K., Urabe D., Inoue M., Arai H. (2012) Identification and structure determination of novel anti-inflammatory mediator resolvin E3, 17,18-dihydroxyeicosapentaenoic acid. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 10525–10534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Urabe D., Todoroki H., Masuda K., Inoue M. (2012) Total syntheses of four possible stereoisomers of resolvin E3. Tetrahedron 68, 3210–3219 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Westphal C., Konkel A., Schunck W.-H. (2011) CYP-eicosanoids--a new link between omega-3 fatty acids and cardiac disease? Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 96, 99–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yanai R., Mulki L., Hasegawa E., Takeuchi K., Sweigard H., Suzuki J., Gaissert P., Vavvas D. G., Sonoda K.-H., Rothe M., Schunck W.-H., Miller J. W., Connor K. M. (2014) Cytochrome P450-generated metabolites derived from ω-3 fatty acids attenuate neovascularization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 9603–9608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold C., Markovic M., Blossey K., Wallukat G., Fischer R., Dechend R., Konkel A., von Schacky C., Luft F. C., Muller D. N., Rothe M., Schunck W.-H. (2010) Arachidonic acid-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes are targets of omega-3 fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 32720–32733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morisseau C., Hammock B. D. (2013) Impact of soluble epoxide hydrolase and epoxyeicosanoids on human health. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 53, 37–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaur G., Cameron-Smith D., Garg M., Sinclair A. J. (2011) Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3): a review of its biological effects. Prog. Lipid Res. 50, 28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies. (2012). Scientific opinion on the tolerable upper intake level of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). EFSA J. 10, 2815–2865 [Google Scholar]

- 31. http://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/ndl U.S. Department of Agriculture Agricultural Research Service and Nutrient Data Laboratory. (2015) USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 28. Version Current: September 2015, slightly revised May 2016. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC. Accessed May 17, 2016 at:

- 32.Miller E., Kaur G., Larsen A., Loh S. P., Linderborg K., Weisinger H. S., Turchini G. M., Cameron-Smith D., Sinclair A. J. (2013) A short-term n-3 DPA supplementation study in humans. Eur. J. Nutr. 52, 895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaur G., Begg D. P., Barr D., Garg M., Cameron-Smith D., Sinclair A. J. (2010) Short-term docosapentaenoic acid (22:5 n-3) supplementation increases tissue docosapentaenoic acid, DHA and EPA concentrations in rats. Br. J. Nutr. 103, 32–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dalli J., Colas R. A., Serhan C. N. (2013) Novel n-3 immunoresolvents: structures and actions. Sci. Rep. 3, 1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sullivan B. L., Brown J., Williams P. G., Meyer B. J. (2008) Dietary validation of a new Australian food-frequency questionnaire that estimates long-chain n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Br. J. Nutr. 99, 660–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan B., Williams P., Meyer B. (2006) Biomarker validation of a long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid food frequency questionnaire. Lipids 41, 845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swierk M., Williams P. G., Wilcox J., Russell K. G., Meyer B. J. (2011) Validation of an Australian electronic food frequency questionnaire to measure polyunsaturated fatty acid intake. Nutrition 27, 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maddipati K. R., Zhou S.-L. (2011) Stability and analysis of eicosanoids and docosanoids in tissue culture media. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 94, 59–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markworth J. F., Vella L., Lingard B. S., Tull D. L., Rupasinghe T. W., Sinclair A. J., Maddipati K. R., Cameron-Smith D. (2013) Human inflammatory and resolving lipid mediator responses to resistance exercise and ibuprofen treatment. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 305, R1281–R1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akiba S., Murata T., Kitatani K., Sato T. (2000) Involvement of lipoxygenase pathway in docosapentaenoic acid-induced inhibition of platelet aggregation. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 23, 1293–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Phang M., Garg M. L., Sinclair A. J. (2009) Inhibition of platelet aggregation by omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids is gender specific-Redefining platelet response to fish oils. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 81, 35–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanayasu-Toyoda T., Morita I., Murota S. (1996) Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5, n-3), an elongation metabolite of eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5, n-3), is a potent stimulator of endothelial cell migration on pretreatment in vitro. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 54, 319–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuji M., Murota S. I., Morita I. (2003) Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5, n-3) suppressed tube-forming activity in endothelial cells induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 68, 337–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morin C., Rousseau É., Fortin S. (2013) Anti-proliferative effects of a new docosapentaenoic acid monoacylglyceride in colorectal carcinoma cells. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 89, 203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaur G., Sinclair A. J., Cameron-Smith D., Barr D. P., Molero-Navajas J. C., Konstantopoulos N. (2011) Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3) down-regulates the expression of genes involved in fat synthesis in liver cells. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 85, 155–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holub B. J., Swidinsky P., Park E. (2011) Oral docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3) is differentially incorporated into phospholipid pools and differentially metabolized to eicosapentaenoic acid in tissues from young rats. Lipids 46, 399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen J., Jiang Y., Liang Y., Tian X., Peng C., Ma K. Y., Liu J., Huang Y., Chen Z.-Y. (2012) DPA n-3, DPA n-6 and DHA improve lipoprotein profiles and aortic function in hamsters fed a high cholesterol diet. Atherosclerosis 221, 397–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gotoh N., Nagao K., Onoda S., Shirouchi B., Furuya K., Nagai T., Mizobe H., Ichioka K., Watanabe H., Yanagita T., Wada S. (2009) Effects of three different highly purified n-3 series highly unsaturated fatty acids on lipid metabolism in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 11047–11054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kelly L., Grehan B., Chiesa A. D., O’Mara S. M., Downer E., Sahyoun G., Massey K. A., Nicolaou A., Lynch M. A. (2011) The polyunsaturated fatty acids, EPA and DPA exert a protective effect in the hippocampus of the aged rat. Neurobiol. Aging 32, 2318.e1–2318.e15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oda E., Hatada K., Katoh K., Kodama M., Nakamura Y., Aizawa Y. (2005) A case-control pilot study on n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid as a negative risk factor for myocardial infarction. Int. Heart J. 46, 583–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rissanen T., Voutilainen S., Nyyssönen K., Lakka T. A., Salonen J. T. (2000) Fish oil-derived fatty acids, docosahexaenoic acid and docosapentaenoic acid, and the risk of acute coronary events: the Kuopio ischaemic heart disease risk factor study. Circulation 102, 2677–2679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Paganelli F., Maixent J. M., Duran M. J., Parhizgar R., Pieroni G., Sennoune S. (2001) Altered erythrocyte n-3 fatty acids in Mediterranean patients with coronary artery disease. Int. J. Cardiol. 78, 27–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sun Q., Ma J., Campos H., Rexrode K. M., Albert C. M., Mozaffarian D., Hu F. B. (2008) Blood concentrations of individual long-chain n-3 fatty acids and risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 88, 216–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fischer R., Konkel A., Mehling H., Blossey K., Gapelyuk A., Wessel N., von Schacky C., Dechend R. Muller D. N., Rothe M., Luft F. C., Weylandt K. Schunck W.-H. (2014). Dietary omega-3 fatty acids modulate the eicosanoid profile in man primarily via the CYP-epoxygenase pathway. J. Lipid Res. 55, 1150–1164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Keenan A. H., Pedersen T. L., Fillaus K., Larson M. K., Shearer G. C., Newman J. W. (2012) Basal omega-3 fatty acid status affects fatty acid and oxylipin responses to high-dose n3-HUFA in healthy volunteers. J. Lipid Res. 53, 1662–1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lundström S. L., Yang J., Brannan J. D., Haeggström J. Z., Hammock B. D., Nair P., O’Byrne P., Dahlén S.-E., Wheelock C. E. (2013) Lipid mediator serum profiles in asthmatics significantly shift following dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 57, 1378–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schuchardt J. P., Schmidt S., Kressel G., Willenberg I., Hammock B. D., Hahn A., Schebb N. H. (2014) Modulation of blood oxylipin levels by long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation in hyper- and normolipidemic men. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids 90, 27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shearer G. C., Harris W. S., Pedersen T. L., Newman J. W. (2010) Detection of omega-3 oxylipins in human plasma and response to treatment with omega-3 acid ethyl esters. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2074–2081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mas E., Barden A., Burke V., Beilin L. J., Watts G. F., Huang R. C., Puddey I. B., Irish A. B., Mori T. A. (2016) A randomized controlled trial of the effects of n-3 fatty acids on resolvins in chronic kidney disease. Clin. Nutr. 35, 331–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schebb N. H., Ostermann A. I., Yang J., Hammock B. D., Hahn A., Schuchardt J. P. (2014) Comparison of the effects of long-chain omega-3 fatty acid supplementation on plasma levels of free and esterified oxylipins. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 113-115, 21–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zulyniak M. A., Perreault M., Gerling C., Spriet L. L., Mutch D. M. (2013) Fish oil supplementation alters circulating eicosanoid concentrations in young healthy men. Metabolism 62, 1107–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Skarke C., Alamuddin N., Lawson J. A., Li X., Ferguson J. F., Reilly M. P., FitzGerald G. A. (2015) Bioactive products formed in humans from fish oils. J. Lipid Res. 56, 1808–1820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dawczynski C., Massey K. A., Ness C., Kiehntopf M., Stepanow S., Platzer M., Grün M., Nicolaou A., Jahreis G. (2013) Randomized placebo-controlled intervention with n-3 LC-PUFA-supplemented yoghurt: effects on circulating eicosanoids and cardiovascular risk factors. Clin. Nutr. 32, 686–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gomolka B., Siegert E., Blossey K., Schunck W.-H., Rothe M., Weylandt K. H. (2011) Analysis of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid-derived lipid metabolite formation in human and mouse blood samples. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 94, 81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Colas R. A., Shinohara M., Dalli J., Chiang N., Serhan C. N. (2014) Identification and signature profiles for pro-resolving and inflammatory lipid mediators in human tissue. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 307, C39–C54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Barden A., Mas E., Croft K. D., Phillips M., Mori T. A. (2014) Short-term n-3 fatty acid supplementation but not aspirin increases plasma proresolving mediators of inflammation. J. Lipid Res. 55, 2401–2407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mas E., Croft K. D., Zahra P., Barden A., Mori T. A. (2012) Resolvins D1, D2, and other mediators of self-limited resolution of inflammation in human blood following n-3 fatty acid supplementation. Clin. Chem. 58, 1476–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Psychogios N., Hau D. D., Peng J., Guo A. C., Mandal R., Bouatra S., Sinelnikov I., Krishnamurthy R., Eisner R., Gautam B., Young N., Xia J., Knox C., Dong E., Huang P., Hollander Z., Pedersen T. L., Smith S. R., Bamforth F., Greiner R., McManus B., Newman J. W., Goodfriend T., Wishart D. S. (2011) The human serum metabolome. PLoS One 6, e16957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murphy R. C. (2015) Specialized pro-resolving mediators: do they circulate in plasma? J. Lipid Res. 56, 1641–1642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schuchardt J. P., Schneider I., Willenberg I., Yang J., Hammock B. D., Hahn A., Schebb N. H. (2014) Increase of EPA-derived hydroxy, epoxy and dihydroxy fatty acid levels in human plasma after a single dose of long-chain omega-3 PUFA. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 109-111, 23–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamada H., Oshiro E., Kikuchi S., Hakozaki M., Takahashi H., Kimura K. (2014) Hydroxyeicosapentaenoic acids from the Pacific krill show high ligand activities for PPARs. J. Lipid Res. 55, 895–904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harmon G. S., Dumlao D. S., Ng D. T., Barrett K. E., Dennis E. A., Dong H., Glass C. K. (2010) Pharmacological correction of a defect in PPAR-gamma signaling ameliorates disease severity in Cftr-deficient mice. Nat. Med. 16, 313–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu D., Han C., Wu T. (2014) 15-PGDH inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma growth through 15-keto-PGE2/PPARγ-mediated activation of p21WAF1/Cip1. Oncogene 33, 1101–1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ghasemifard S., Turchini G. M., Sinclair A. J. (2014) Omega-3 long chain fatty acid “bioavailability”: a review of evidence and methodological considerations. Prog. Lipid Res. 56, 92–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]