Abstract

Antigen presentation to the T-cell receptor leads to sustained cytosolic Ca2+ elevation, which is critical for T-cell activation. We previously showed that in activated T cells, Ca2+ clearance is inhibited by the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ sensor stromal interacting molecule 1 (STIM1) via association with the plasma membrane Ca2+/ATPase 4 (PMCA4) Ca2+ pump. Having further observed that expression of both proteins is increased in activated T cells, the current study focused on mechanisms regulating both up-regulation of STIM1 and PMCA4 and assessing how this up-regulation contributes to control of Ca2+ clearance. Using a STIM1 promoter luciferase vector, we found that the zinc finger transcription factors early growth response (EGR) 1 and EGR4, but not EGR2 or EGR3, drive luciferase activity. We further found that neither STIM1 nor PMCA4 is up-regulated when both EGR1 and EGR4 are knocked down using RNA interference. Further, under these conditions, activation-induced Ca2+ clearance inhibition was eliminated with little effect on Ca2+ entry. Finally, we found that nuclear factor of activated T-cell (NFAT) activity is profoundly attenuated if Ca2+ clearance is not inhibited by STIM1. These findings reveal a critical role for STIM1-mediated control of Ca2+ clearance in NFAT induction during T-cell activation.—Samakai, E., Hooper, R., Martin, K. A., Shmurak, M., Zhang, Y., Kappes, D. J., Tempera, I., Soboloff, J. Novel STIM1-dependent control of Ca2+ clearance regulates NFAT activity during T-cell activation.

Keywords: calcium, EGR1, EGR4, Jurkat, PMCA4, SOCe

The T-cell receptor (TCR) is a complex of integral membrane proteins that participates in the activation of T cells in response to the presentation of antigen. When T cells are engaged by antigen-presenting cells, an immunologic synapse forms, resulting in TCR-mediated phospholipase C-γ activation and the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Increased cytosolic Ca2+ in turn leads to calcineurin activation, which dephosphorylates nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT), resulting in its nuclear translocation (1, 2). Because of the presence of nuclear kinases, this translocation is highly transient; sustained nuclear localization of NFAT therefore requires sustained Ca2+ elevation. Maintaining elevated cytosolic Ca2+ levels for more than a few minutes is an unusual physiologic scenario, requiring novel regulatory mechanisms.

A central mediator of elevated Ca2+ levels is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) transmembrane protein stromal interacting molecule 1 (STIM1). Decreases in ER Ca2+ content are sensed by STIM1, causing it to translocate within the ER toward the plasma membrane, where it interacts with the Orai1 channel, resulting in its activation and Ca2+ influx (3). It has been well established that this is a required event for nuclear localization of NFAT activation and T-cell activation (4–6). Recently, we showed that in addition to stimulating Ca2+ entry, translocation of STIM1 and plasma membrane Ca2+/ATPase 4 (PMCA4) to the immunologic synapse leads to loss of PMCA4 function and decreased Ca2+ clearance rate (7). Interestingly, Quintana et al. (8) made a similar observation, although they attributed inhibition of PMCA4 function during T-cell activation to mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake. Irrespective of the role played by mitochondria for control of Ca2+ clearance, we previously established that these are distinct phenomena (7). The current investigation thus focused primarily on understanding STIM1-dependent mechanisms in control of PMCA4 function. In addition, the downstream consequences of PMCA4 inhibition during T-cell activation on NFAT activation have not previously been determined.

Upon TCR engagement, both STIM1 and PMCA4 become up-regulated (7). Because STIM1 knockdown attenuated its ability to inhibit PMCA4 while STIM1 overexpression led to PMCA4 inhibition independent of T-cell activation state, transcriptional mechanisms regulating the expression of these proteins may be the first step in the engagement of this interaction. In a previous study, we showed that the transcription factor early growth response 1 (EGR1) is a positive regulator of STIM1 expression (9). Although EGR1 up-regulation was observed with T-cell activation (7), no loss of STIM1 expression was observed in EGR1 knockout thymus (9). EGR1 is a member of the EGR family of zinc finger transcription factors; the roles of the remaining 3 family members in STIM1 regulation were not determined. In the current study, we found that both EGR1 and EGR4 participate in the control of STIM1 expression in T cells. We further found that STIM1 up-regulation during T-cell activation has little or no impact on store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCe) but is required for PMCA4 inhibition. Finally, we found that these events contribute to efficient NFAT activation in T cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture

Jurkat T cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. All cells were maintained at 37°C at 5% CO2.

Plasmids

cDNAs encoding eYFP-tagged human STIM1 (YFP-STIM1), YFP-STIM1Δ597, construct were generated as previously described (7). The NFAT luciferase vector was generously provided by J. Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA). The STIM1 luciferase vector was generated in an NF-κB luciferase vector by replacing the NF-κB sites with a portion of the STIM1 promoter (−538 to +242). Stealth EGR1 (position 854, 5′-CAUCCAACGACAGCAGUCCCAUUUA-3′; position 1493, 5′-GCUUUCGGACAUGACAGCAACCUUU-3′), EGR4 (position 1733, 5′-GCGAUGAGAAGAAACGGCACAGCAA-3′), and STIM2 (position 2170, 5′-AAGGCAAGGAGUGUGGUGUGUGUUG-3′) short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were designed using the Block-it siRNA designer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Human EGR1 was generously provided by K. Tew (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA). Human EGR2 and human EGR3 were obtained from L. Glimcher (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, USA). Human EGR4 was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD, USA). The STIM1 luciferase vector was generated by insertion of a 780 bp sequence (−538 to +242 bp; synthesized by GenScript, Piscataway, NJ, USA) from the human STIM1 promoter into a firefly luciferase vector [hereafter referred to as STIM1 luciferase vector (S1-Luc)]. Medium GC-rich RNA interference (RNAi) control (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as a scrambled sequence.

Transfection

Cells were transfected with empty vector alone or siRNA targeting EGR1 or EGR4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Transfections were carried out using the Nucleofactor device corresponding kits (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany). Transfection protocols were performed following the manufacturer's instructions using the X-005 program.

Cell lysis and Western blot

Cells were lysed in CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate) lysis buffer (35 mM CHAPS, 150 mM NaCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM EDTA pH 8.0 with protease inhibitors), cleared by centrifugation, and normalized for protein content (determined using the DC protein assay kit; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Proteins were resolved on 10% SDS-PAGE gels transferred to PVDF paper and analyzed with the indicated antibodies as previously described (9).

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using RNA-Bee reagent (Tel-Test, Friendswood, TX, USA). Briefly, 1 ml of RNA-Bee reagent was added per 10 cm culture dish. Homogenate was stored on ice for 5 min, followed by the addition of 0.2 ml chloroform to allow for phase separation. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and then centrifuged at 4°C at 12,000 g for 15 min. Aqueous phase was removed and mixed with 0.5 ml isopropanol, followed by centrifugation at 4°C at 12,000 g for 5 min to allow for RNA precipitation. RNA was then washed with 1 ml ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 4°C at 6000 g for 5 min. RT-PCR was completed as a 2-step process using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription (Thermo Fisher Scientific), followed by SYBR Green PCR (Thermo Fisher Scientific on a 7300 Real-Time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The real-time reaction was carried out by a 10 min incubation at 95°C and 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C 1 min for annealing. Data are presented as the level relative to the expression of control sequence (Tata-box binding protein, TBP) using the following primers: EGR1, human: sense 5′-CCCTCAATACCAGCTACCA-3′, antisense 5′-TCCACTGGGCAAGCGTAA-3′; EGR2, human: sense 5′-CAAGTTCTCCATTGACCCTC-3′, antisense 3′-GGTGACGCTGGATGAGG-5′; EGR3, human: sense 5′-GCCAGGACAACATCATTAG-3′, antisense 5′-TAGAGGTCGCCGCAGT-3′; EGR4: human: sense 5′-TGTGGGTCACAGGGAGACTAC-3′, antisense 5′-CGCTGGGATAGAGTCTGTTGG-3′; STIM2, human: sense 5′-GGGGTTCTCCCGACTGT-3′, antisense 5′-TGTGGCGAGGTTTAGGC-3′; and TBP, human: sense 5′-CAGCCGTTCAGCAGTCAA-3′, antisense 5′-GGAGGGATACAGTGGAGT-3′.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9 system targeting human STIM1 and stable cell line

Human clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 guide RNA (gRNA) primers were designed at CRISPR Design (http://crispr.mit.edu/), targeting exon 1 of human STIM1. Two STIM1 gRNA sequences were chosen on the basis of predicted specificity: STIM1 gRNA: 5′-TATGCGTCCGTCTTGCCCTG-3′ and 5′-AGGCGACAGGAACCAGCTCG-3′. These sequences were cloned into the pSpCAS9 (BB)-2A-Puro (PX459) and pYSY-gRNA-mCherry vectors, generously provided by J. Huang (Temple University). The plasmids were then cotransfected into Jurkat cells by electroporation using Gene pulser (Bio-Rad). Cells were selected with 2 μg/ml puromycin, sorted for mCherry expression, and then cloned. After several weeks of growth, cells were screened for loss of SOCe by fluorescence microscopy; successful deletion of STIM1 was confirmed by Western blot analysis and sequencing (Genewiz, South Plainfield, NJ, USA).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed according to the protocol provided by Thermo Fisher Scientific with minor modifications as previously described (10, 11). Additional modifications were as follows. Cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 15 min. DNA was sonicated using a sonic Dismembrator (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to generate 200 to 300 bp DNA fragments. Real-time PCR was performed with SYBR Green on a 7300 Real-Time PCR machine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 1% of the ChIP DNA. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated with a polyclonal antibodies for EGR1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Luciferase reporter gene assay

The enzymatic activity of NFAT was quantified by using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After 48 h transfection with 8 μg of NFAT-luciferase reporter gene and 2 μg of Renilla gene to normalize for luciferase activity and control for transfection efficiency, Jurkat T cells were activated with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 for 8 h. Cell lysates were prepared, and luciferase activity was measured with a Victor ×5 multilabel plate reader using the dual-luciferase reporter system according to the manufacturer (Promega).

Cytosolic Ca2+ measurements

Cells were plated on coverslips coated with either poly-l-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) or anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and placed in cation-safe solution (107 mM NaCl, 7.2 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 11.5 mM glucose, 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, 1 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2), then loaded with fura-2/acetoxymethylester (2 µM) for 30 min at 24°C. Cells were washed, and dye was allowed to deesterify for a minimum of 30 min at 24°C. Approximately 85% of the dye was confined to the cytoplasm as determined by the signal remaining after saponin permeabilization. Ca2+ measurements were made using a DMI 6000B fluorescence microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) controlled by Slidebook Software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO, USA). Fluorescence emission at 505 nm was monitored while alternating between 340 and 380 nm excitation wavelengths at a frequency of 0.67 Hz; intracellular Ca2+ measurements are shown as 340/380 nm ratios obtained from groups (35 to 45) of single cells. For measurement of Ca2+ clearance, cells were cultured in serum-free medium containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 12 h before a 2 h activation period before beginning each experiment. To both induce SOCe and measure PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance, the function of sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium transport ATPase (SERCA) was inhibited by the addition of thapsigargin (Tg; 2 µM). Ca2+ was added after recovery of cytosolic Ca2+ content and then removed once peak levels had been reached to measure Ca2+ clearance.

Materials

Anti-STIM1 (#4149) and anti-STIM2 (#4917) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). Anti-EGR1 (C-19) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti‐rabbit and rabbit anti‐mouse antibodies were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Anti-human CD3 and anti-human CD28 were purchased from Affymetrix. Fura-2/acetoxymethylester and Tg were from EMD Biosciences (San Diego, CA, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Control of STIM1 and PMCA4 expression by the EGR family of transcription factors

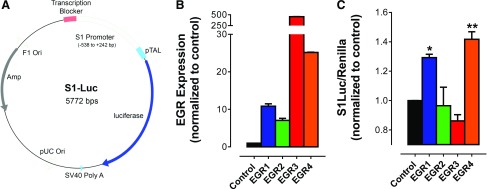

In a prior study investigating control of STIM1 expression by EGR1, we observed that EGR1 deficiency caused marked loss of STIM1 expression in kidney, liver, spleen, and brain but not in whole thymus (9). Insensitivity of thymic STIM1 expression to EGR1 deficiency could reflect thymus-specific compensation by other EGR family members. Hence, it is important to assess whether other EGR family members can regulate STIM1 expression in T cells. Accordingly, we coexpressed each EGR isoform in Jurkat T cells together with a luciferase reporter controlled by the proximal STIM1 promoter containing multiple EGR binding sites (Fig. 1A). For unknown reasons, ectopic expression of EGR3 and EGR4 was considerably higher than EGR1 or EGR2 despite equivalent transfection efficiencies (Fig. 1B). Nevertheless, these experiments clearly showed that only EGR1 and EGR4 could induce reporter expression (Fig. 1C). This indicates that EGR1 and EGR4 exhibit the capacity to activate the STIM1 promoter, whereas EGR2 and EGR3 lack this ability. Interestingly, the ability of EGR4 to compensate for loss of EGR1 function was previously reported for control of luteinizing hormone expression (12). Given that EGR1 and EGR4 share unique capacity among EGR family members to control STIM1 transcription, we then assessed the potential relevance of dual regulation by EGR1 and EGR4 for controlling STIM1 expression in a T-cell model.

Figure 1.

Modulation of STIM1 expression by EGR4 knockdown. Jurkat T cells were transfected with each of STIM1 luciferase along with each EGR family member and Renilla control vector. A) Vector map of STIM1 luciferase vector in which EGR binding site containing region of STIM1 promoter was inserted 5′ to luciferase gene. B) Overexpression of each EGR was verified with quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). C) Luciferase activity obtained from cells 24 h after transfection. Statistical analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Redundant EGR1/EGR4-mediated control of STIM1 and PMCA4 expression

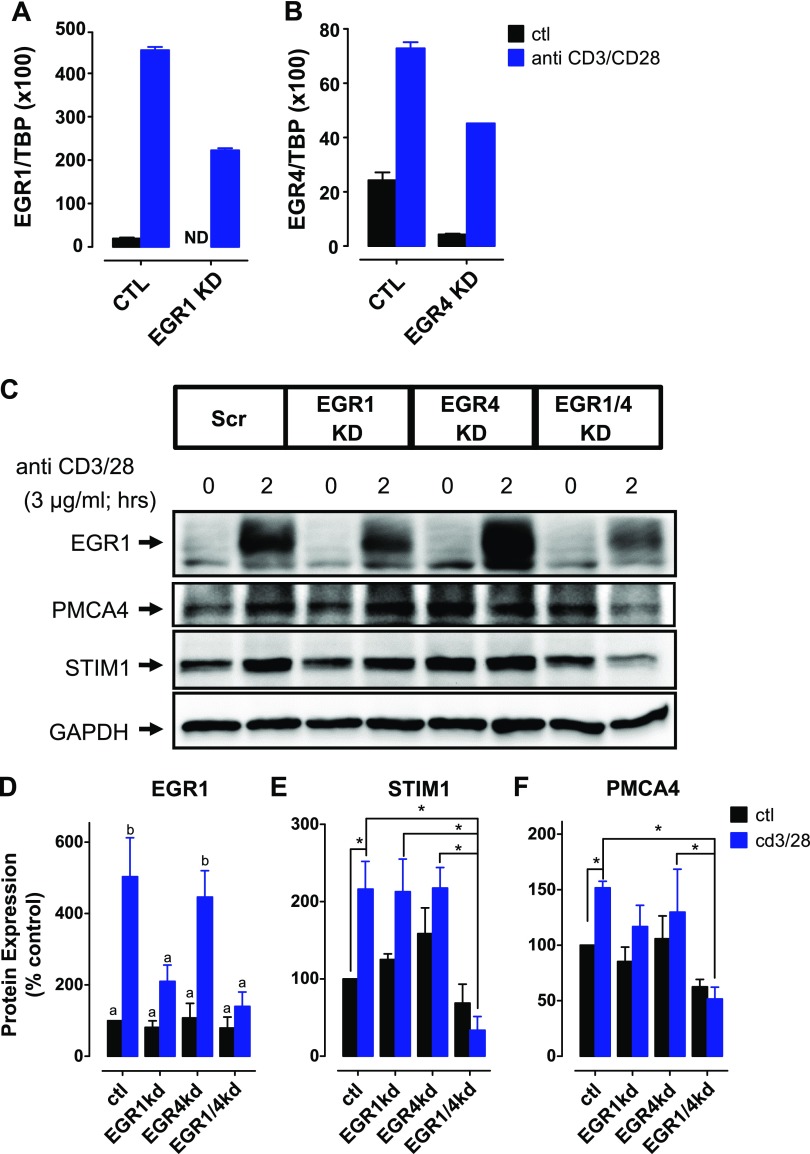

To assess the relative roles of EGR1 and EGR4 as regulators of STIM1 expression, each gene was knocked down in Jurkat T cells using a specific RNAi. The effect of knockdown was compared in unstimulated versus anti-CD3/CD28 activated Jurkat T cells. Activation led to rapid up-regulation of EGR1 protein, as revealed by Western blot (Fig. 2C; presumably the same is true for EGR4 protein, although there is no suitable antibody to detect it). RNAi-mediated knockdown attenuated EGR1 induction by ∼50% and EGR4 induction by 40% (Fig. 2A–D). Neither individual knockdown led to any significant reduction in STIM1 expression in Jurkat T cells under either control or activated conditions. However, knockdown of both EGR1 and EGR4 caused a significant reduction in STIM1 expression in cells activated with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies (Fig. 2C, E). Given our previous finding that T-cell activation also leads to increased expression of PMCA4 (7), we examined whether this PMCA4 up-regulation was dependent on EGR1 and/or EGR4. Interestingly, like STIM1, PMCA4 was significantly reduced in response to simultaneous knockdown of EGR1 and EGR4, but not individual knockdown in activated cells only (Fig. 2C, F). To our knowledge, this is the first evidence that EGR1 and EGR4 cooperatively regulate either STIM1 or PMCA4 expression.

Figure 2.

EGR1 and EGR4 are both required for STIM1 expression. A, B) Expression levels of STIM1 and PMCA4 were determined after knockdown (KD) of EGR1 and/or EGR4. Knockdown of both EGR1 (A) and EGR4 (B) was confirmed by qRT-PCR. C) Representative Western blot of EGR1, STIM1, and PMCA4 expression levels in Jurkat T cells transfected with EGR1 and/or EGR4 siRNA. Cells were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies for time periods indicated. D–F) Densitometric analysis of EGR1 (D), STIM1 (E), and PMCA4 (F) expression level determined from Western blots as depicted in C (n = 3). Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Fisher’s multiple comparisons. D) Representation of 2 statistically different groups (a–b); P < 0.05. E, F) Asterisk denotes statistical difference. *P < 0.05.

The level of expression of any protein reflects both the rate of translation and the rate of degradation. While we were initially surprised by the rapid reduction in both STIM1 and PMCA4 expression upon T-cell activation, it is important to recognize that up-regulation of protein degradation pathways is a defining feature of T-cell activation (13–16). Hence, the somewhat modest increases in STIM1 expression observed without EGR1/EGR4 knockdown may actually reflect a much larger EGR1/EGR4-dependent increase in STIM1 transcription/translation, tempered by increased protein degradation. Considering that EGR1 and EGR4 are transcription factors, a study of protein degradation pathways is outside the scope of the present study. Instead, we have focused on direct transcriptional effects of EGR1 and EGR4. To determine whether EGR-mediated control of both STIM1 and PMCA4 expression is direct, we next examined EGR binding to their proximal promoters by ChIP.

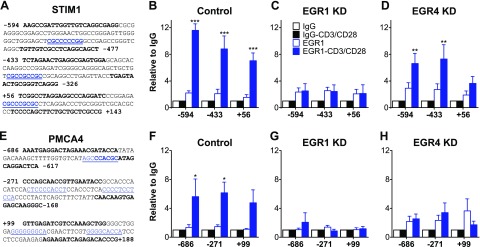

Defining EGR binding sites on the STIM1 and PMCA4 promoters

We have previously shown that EGR1 binds directly to the STIM1 promoter in HEK293 and G401 rhabdoid tumor cells (9), but T cells were not examined. These studies identified 4 EGR consensus sites within the STIM1 promoter, 2 of which were shown to be functional (9) (Fig. 3A; blue regions in DNA segments labeled −433 and +56). Additional analysis of proximal sequences near the STIM1 transcriptional start site (TSS) revealed another potential site about 200 bp further upstream (Fig. 3A; blue regions in DNA segments labeled −594). Similar analysis of the PMCA promoter revealed 2 potential EGR response elements upstream of the TSS and 1 downstream of the TSS (Fig. 3E). Given our hypothesis that EGR1 and EGR4 regulate STIM1 expression in conjunction, it would be ideal to determine by ChIP whether each of these sites binds EGR1, EGR4, or both. However, because ChIP-quality EGR4 antibodies are not currently available, our analysis is so far restricted to EGR1. Unstimulated T cells do not show any EGR1 binding to either the STIM1 or PMCA4 promoters (Fig. 3B, F) because they do not express detectable EGR1 (Fig. 2). Upon activation, substantial EGR1 binding was observed at each putative consensus site within the STIM1 and PMCA4 promoters (Fig. 3B, F). As expected, transfection with EGR1 siRNA eliminated EGR1 binding at all sites (Fig. 3C, G). Interestingly, EGR4 knockdown decreased EGR1 binding to both the STIM1 and PMCA4 promoters, particularly the PMCA4 promoter and the +56 site of the STIM1 promoter where no significant EGR1 binding could be detected in activated cells (Fig. 3D, H). These observations indicate that decreased EGR4 expression has a substantial negative impact on EGR1 binding and support a cooperative model in which EGR4 promotes binding of EGR1 to the STIM1 and PMCA4 promoters, thereby facilitating up-regulation of both STIM1 and PMCA4 upon T cell-activation.

Figure 3.

ChIP analysis of EGR1 binding to STIM1 and PMCA promoter in T cells. A, E) Sequence analysis reveals several putative EGR binding sites near STIM1 (A) and PMCA4 (E) TSSs. B, F) Analysis of ChIP efficiency by qRT-PCR reveals distinct binding patterns for EGR1 before and 2 h after T-cell activation. C, D, G, H) EGR1 binding was also assessed after EGR1 (C, G) and EGR4 (D, H) RNAi. Data were analyzed by 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. KD, knockdown. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Loss of both EGR1/4 expression affects Ca2+ clearance and not Ca2+ entry

Given the primary role of STIM1 and PMCA4 as regulators of Ca2+ signaling, we performed Ca2+ entry and clearance assays, using a modified version of our previously described approach (7), to test whether EGR knockdown impairs Ca2+ signaling. Briefly, Jurkat T cells were plated on either poly-l-lysine (control) or anti-CD3/28 antibodies (activated) for 2 h, then treated with Tg in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ to deplete ER Ca2+ stores. Subsequent addition of extracellular Ca2+ induces a change in cytosolic Ca2+ that reflects SOCe, while the rate at which cytosolic Ca2+ returns to baseline after extracellular Ca2+ removal reflects PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance (Fig. 4A). Ca2+ clearance was fit to exponential decay, utilizing an F test to determine whether or not 2-phase or 1-phase decay was appropriate. Consistent with prior studies (7), Jurkat cells transfected with scrambled RNAi showed close fit of Ca2+ clearance to 2-phase exponential decay (Table 1), while CD3/CD28-induced activation delayed the second, slower phase of Ca2+ clearance (Fig. 4B). However, after knocking down EGR1 and EGR4, we did not observe any activation-induced PMCA inhibition (Fig. 4C, E). Moreover, after EGR1/4 knockdown, the second, slow Ca2+ clearance phase was severely attenuated, such that the difference in τ was reduced from a 4- to 6-fold difference in wild type (WT) Jurkat cells to an only 2-fold difference in resting cells (Fig. 4E and Table 1). Further, after activation, the second phase of Ca2+ clearance was essentially eliminated, with no significant difference between τ1 and τ2 (Table 1). As expected, Tg responses were similar in cells transfected with scrambled or EGR1 and EGR4 siRNA (Supplemental Fig. S1), so differences in store depletion or SERCA inhibition did not contribute to these changes. Finally, because EGR1 and EGR4 are transcription factors with multiple targets, we coexpressed STIM1 with EGR1 and EGR4 siRNA to assess the STIM1 dependence of the Ca2+ clearance differences reported above. Coexpression of STIM1WT with EGR1 and EGR4 siRNA both restored 2-phase Ca2+ clearance dynamics and profoundly delayed the second Ca2+ clearance phase (Fig. 4D and Table 1). In contrast, coexpressing siRNA targeting EGR1 and EGR4 with STIM1Δ597, a truncation mutant incapable of inhibiting PMCA, failed to restore the second phase of Ca2+ clearance (Fig. 4D and Table 1). On the basis of these findings, it seems clear that during T-cell activation, EGR-mediated STIM1 up-regulation is a required component of delayed Ca2+ clearance.

Figure 4.

EGR1/4 knockdown (KD) reduced activation-dependent inhibition of Ca2+ clearance. Ca2+ entry and clearance were measured in Jurkat T cells plated for 2 h on coverslips coated with poly-l-lysine (control) or anti-CD3/CD28 (3 µg/ml; activated). A) ER Ca2+ stores of fura-2-loaded cells were depleted with Tg (2 µM; arrow) in absence of [Ca2+]e. (Sample of whole trace is shown.) Subsequent elevation of [Ca2+]e to 1 mM led to elevated [Ca2+]c; rates of Ca2+ clearance were then measured starting from point that [Ca2+]e was again removed. B–E) Ca2+ clearance measured in T cells transfected with scrambled RNA (B) or both EGR1 and EGR4 siRNA (C, E) or both EGR1 and EGR4 siRNA along with either STIM1WT or STIM1Δ597 (D). F) Peak Ca2+ entry was measured from experiments in panels B–E and compared in all conditions by 1-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. **P < 0.01 compared to nonactivated cells transfected with EGR1/4 siRNA. G–I) Cells were treated as indicated before measuring Ca2+ entry and clearance (see Supplemental Fig. S2D, E). No differences in peak Ca2+ entry were observed under these conditions, as determined by 2-way ANOVA.

TABLE 1.

Calculated nonlinear regression constants from Ca2+ clearance assays

| Parameter | Scrambled siRNA | EGR1/EGR4 siRNA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STIM1 | — | — | — | — | WT | Δ597 |

| Coverslip | Poly-lysine | CD3/28 | Poly-lysine | CD3/28 | Poly-lysine | Poly-lysine |

| N | 10 | 13 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| Peak Ca2+ | 6.84 ± 0.33 | 7.55 ± 0.25 | 5.93 ± 0.46 | 7.87 ± 0.25 | 8.00 ± 0.26 | 8.61 ± 0.29 |

| Two-phase, preferred | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0431 | P = 0.2230 | P < 0.0001 | incalculable |

| Two-phase R2 | 0.752 | 0.778 | 0.744 | 0.812 | 0.84 | ND |

| τ1 | 14.1 ± 0.85 | 16.8 ± 0.68 | 12.0 ± 2.51 | 13.1 ± 5.93 | 14.2 ± 0.26 | ND |

| τ2 | 59.1 ± 24.2 | 92.9 ± 14.9 | 25.3 ± 16.0 | 20.8 ± 15.6 | 266 ± 20.3 | ND |

| One-phase R2 | 0.750 | 0.771 | 0.743 | 0.812 | 0.797 | 0.813 |

| τ1 | 16.3 ± 0.32 | 22.11 ± 0.35 | 14.3 ± 0.28 | 15.6 ± 0.23 | 20.8 ± 0.27 | 11.6 ± 0.17 |

| Y0, preferred | 4.42 ± 0.054 | 5.47 ± 0.053 | 3.72 ± 0.048 | 4.95 ± 0.051 | 6.33 ± 0.045 | 5.23 ± 0.041 |

| Plateau, preferred | 0.75 ± 0.007 | 0.89 ± 0.009 | 0.70 ± 0.004 | 0.82 ± 0.004 | 0.70 ± 0.017 | 0.89 ± 0.004 |

Constants were obtained from the equations Y = B + A1 * e−X/ τ1 + A2 * e−X/τ2 or Y = B + A1 * e−X/ τ1,where B is the plateau of decay and τ1 and τ2 are time constants for the fast and slow phase, respectively. A1 and A2 are amplitudes for fast and slow phase of decay, respectively; X is time. ND, not done.

STIM1 is most widely studied as a required component of SOCe, and our preliminary predictions were that increases in STIM1 expression would lead to increased SOCe. In retrospect, that fact that changes in SOCe were relatively minor under all conditions studied (Table 1, Fig. 4F and Supplemental Fig. S2) is perhaps not so surprising considering that even manyfold increases in STIM1 expression level via overexpression have very little effect on the magnitude of SOCe unless coexpressed with Orai1 (17–20). This likely reflects a STIM1:Orai1 expression ratio that is above that necessary for optimal SOCe. While we do not have any data on the stoichiometry of STIM1-PMCA4 interactions, the sensitivity of Ca2+ clearance dynamics to STIM1 expression levels suggests a somewhat different ratio than that observed for STIM1 and Orai1.

Although the changes were relatively small, we consistently observed that cells transfected with EGR1/EGR4 siRNA exhibited statistically significant activation-dependent increases in SOCe (Fig. 4F). Considering that STIM1 expression levels were decreased under these conditions (Fig. 2C, E), we were somewhat surprised by this finding, so we explored this scenario further. Because STIM2 expression also increases when Jurkat T cells are activated (7), we assessed the potential contribution of STIM2 levels to this phenomenon. Consistent with our prior report, activating Jurkat T cells leads to an increase in STIM2 expression (Fig. 4G). However, transfecting cells with siRNA targeting both EGR1 and EGR4 also increased STIM2 expression, with no further activation-dependent differences observed (Fig. 4G). To assess how elevated STIM2 expression contributes to SOCe in control and activated Jurkat T cells, STIM2 expression was decreased with RNAi (Fig. 4H). Interestingly, this manipulation eliminated all activation-dependent differences in peak SOCe, irrespective of the level of expression of EGR1 or EGR4. On the basis of this finding, we attribute EGR-dependent differences in peak Ca2+ entry primarily to differences in STIM2 rather than STIM1 expression. Future investigations may shed new light into the dynamics of this functional shift in STIM dependence.

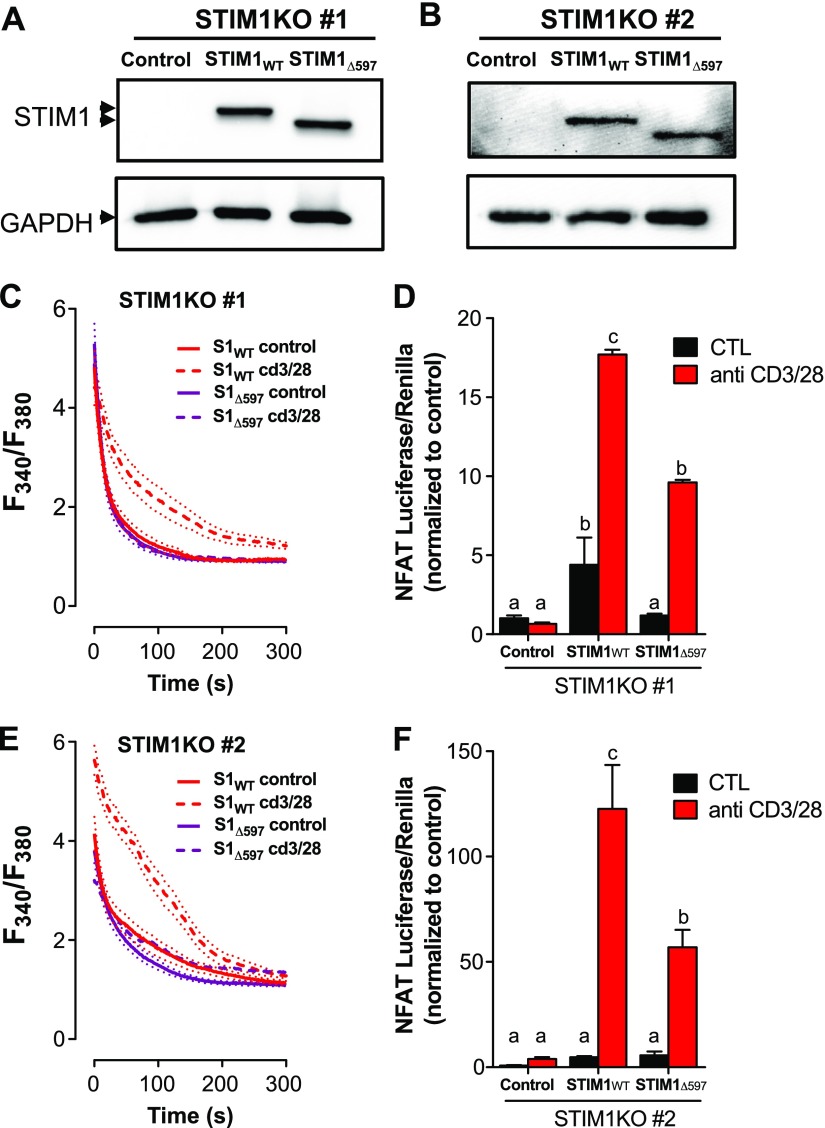

Role of STIM1-mediated PMCA inhibition for control NFAT activation in activated T cells

NFAT activation is critical for T-cell activation and is highly sensitive to changes in cytosolic Ca2+ content. Therefore, we assessed whether inhibition of Ca2+ clearance contributes to NFAT activation in stimulated Jurkat T cells by comparing NFAT luciferase activity in cells expressing STIM1WT or STIM1Δ597. For these studies, we utilized the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate STIM1-null Jurkat T cells. Cells were transfected with 2 plasmids to introduce both Cas9 and 2 gRNA sequences targeting STIM1 exon 1. Cells were cloned and then screened using SOCe to identify candidate cell lines exhibiting STIM1 deletion (Supplemental Fig. S3). Clear loss of SOCe was observed in both clones 1 and 2. Therefore, these cells were transfected with empty vector, STIM1WT, or STIM1Δ597, followed by Western blot analysis and Ca2+ entry and clearance assays. Western blot analysis revealed successful STIM1 deletion in both cell lines (Fig. 5A, B). The STIM1WT or STIM1Δ597 moieties expressed with similar efficiency, although higher expression was observed in clone 1.

Figure 5.

PMCA inhibition is required for NFAT activation. STIM1-knockout (KO) Jurkat T cells were transfected with STIM1WT or STIM1Δ597 and activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 antibodies. A, B) STIM1 expression levels were determined in STIM1-KO#1 (A) and STIM1-KO#2 (B) after transfection with empty vector, STIM1WT, or STIM1Δ597. C, E) Expression differences were validated by Western blot analysis. Ca2+ clearance was measured in STIM1-KO#1(C) and STIM1-KO#2 (E) transfected as in A after plating on poly-l-lysine (control) or anti-CD3/CD28 for 2 h. D, F) STIM1-KO#1 (D) and STIM1-KO#2 (F) were transfected as in A, except for inclusion of NFAT luciferase and Renilla vectors. Cells were incubated in either medium or anti-CD3/CD28 for 8 h before lysis and quantitation of luciferase activity. Data were first normalized to Renilla fluorescence, followed by normalization to control NFAT luciferase activity. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons revealed significant activation- and STIM1-dependent differences in NFAT activity with 3 statistically significant groups (a–c). P < 0.001.

We then examined activation-induced inhibition of Ca2+ clearance, observing a clear delay in the second phase of Ca2+ clearance in cells expressing STIM1WT but not STIM1Δ597 (Fig. 5C, E). We next analyzed NFAT activity by coexpressing each STIM moiety with an NFAT luciferase vector generously provided by J. Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University). While no luciferase activity was observed without STIM1 reexpression, reexpression of STIM1WT, but not STIM1Δ597, led to a modest increase in NFAT-driven luciferase activity in unstimulated cells in clone 1 but not clone 2 (Fig. 5D, F). Activation with anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies led to manyfold increases in NFAT-luciferase activity in either clone, although clone 2 was considerably more responsive than clone 1 (Fig. 5D, F). Despite these apparent clonal differences in the efficiency of STIM1 reexpression and NFAT-luciferase activity, we observed a 50% reduction in luciferase activity in cells expressing STIM1Δ597 relative to STIM1WT. Because there were no differences in the expression of either STIM1 moiety (Fig. 5A, B) and no differences in their ability to facilitate Ca2+ entry (Fig. 4F and Supplemental Fig. S2), these findings reveal a previously unidentified role for STIM1-mediated PMCA4 inhibition for control of NFAT activity during T-cell activation.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings described here reflect a fundamental shift in our understanding of how Ca2+-dependent changes in cell function are achieved. The prototypical “Ca2+ transient” occurs over a seconds- to minutes-long time frame upon receptor engagement; however, achieving and maintaining Ca2+ responses over the hours-long time frame of a TCR-mediated response demands the involvement of alternative regulatory mechanisms. Here we provide multiple insights into the identity of these mechanisms. We discovered that in T cells, full engagement of NFAT requires inhibition of Ca2+ clearance initiated by transcriptional up-regulation of STIM1 and PMCA4. We further found that the zinc finger transcription factors EGR1 and EGR4 are both required for up-regulation of these signaling molecules via cooperative rather than competitive mechanisms. The development of improved tools for studying EGR4 may provide further insights into the dynamics of these transcriptional mechanisms in future studies. Regardless, our investigations reveal the existence of a novel transcriptionally controlled mechanism driving the Ca2+/calcineurin/NFAT axis in intermediate time frames.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank J. Kedra (Temple University) for technical support with this project, M. Ritchie (Champions Oncology, New York, NY, USA) for his efforts developing the STIM1 luciferase construct, J. Pomerantz (Johns Hopkins University) for the NFAT luciferase vector and J. Huang (Temple University) for his assistance with CRISPR/Cas9. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences grants R01GM097335 and R01GM117907 (to J.S.), and F31GM103731 (to E.S.).

Glossary

- CHAPS

3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CRISPR

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats

- EGR

early growth response

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- gRNA

guide RNA

- NFAT

nuclear factor of activated T cells

- PMCA4

plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase 4

- qRT-PCR

quantitative RT-PCR

- RNAi

RNA interference

- S1-Luc

stromal interacting molecule 1 luciferase vector

- SERCA

sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- SOCe

store-operated Ca2+ entry

- STIM1

stromal interacting molecule 1

- TBP

Tata-box binding protein

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- Tg

thapsigargin

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E. Samakai and R. Hooper performed and designed experiments, analyzed data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; K. A. Martin and M. Shmurak performed experiments and analyzed data; D. J. Kappes and Y. Zhang designed experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; I. Tempera designed experiments and contributed to the writing of the manuscript; and J. Soboloff designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith-Garvin J. E., Koretzky G. A., Jordan M. S. (2009) T cell activation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 27, 591–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin J., Weiss A. (2001) T cell receptor signalling. J. Cell Sci. 114, 243–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soboloff J., Rothberg B. S., Madesh M., Gill D. L. (2012) STIM proteins: dynamic calcium signal transducers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 549–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Oh-Hora M., Hogan P. G., Lamperti E. D., Yamashita M., Gelinas C., Neems D. S., Sasaki Y., Feske S., Prakriya M., Rajewsky K., Rao A. (2008) Hair loss and defective T- and B-cell function in mice lacking ORAI1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5209–5222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh-Hora M., Komatsu N., Pishyareh M., Feske S., Hori S., Taniguchi M., Rao A., Takayanagi H. (2013) Agonist-selected T cell development requires strong T cell receptor signaling and store-operated calcium entry. Immunity 38, 881–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh-Hora M., Yamashita M., Hogan P. G., Sharma S., Lamperti E., Chung W., Prakriya M., Feske S., Rao A. (2008) Dual functions for the endoplasmic reticulum calcium sensors STIM1 and STIM2 in T cell activation and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 9, 432–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritchie M. F., Samakai E., Soboloff J. (2012) STIM1 is required for attenuation of PMCA-mediated Ca2+ clearance during T-cell activation. EMBO J. 31, 1123–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quintana A., Pasche M., Junker C., Al-Ansary D., Rieger H., Kummerow C., Nuñez L., Villalobos C., Meraner P., Becherer U., Rettig J., Niemeyer B. A., Hoth M. (2011) Calcium microdomains at the immunological synapse: how ORAI channels, mitochondria and calcium pumps generate local calcium signals for efficient T-cell activation. EMBO J. 30, 3895–3912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ritchie M. F., Yue C., Zhou Y., Houghton P. J., Soboloff J. (2010) Wilms tumor suppressor 1 (WT1) and early growth response 1 (EGR1) are regulators of STIM1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10591–10596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tempera I., Wiedmer A., Dheekollu J., Lieberman P. M. (2010) CTCF prevents the epigenetic drift of EBV latency promoter Qp. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tempera I., Klichinsky M., Lieberman P. M. (2011) EBV latency types adopt alternative chromatin conformations. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tourtellotte W. G., Nagarajan R., Bartke A., Milbrandt J. (2000) Functional compensation by Egr4 in Egr1-dependent luteinizing hormone regulation and Leydig cell steroidogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5261–5268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronietzki A. W., Schuster M., Schmitz I. (2015) Autophagy in T-cell development, activation and differentiation. Immunol. Cell Biol. 93, 25–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deretic V., Saitoh T., Akira S. (2013) Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 722–737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Puleston D. J., Simon A. K. (2014) Autophagy in the immune system. Immunology 141, 1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valdor R., Mocholi E., Botbol Y., Guerrero-Ros I., Chandra D., Koga H., Gravekamp C., Cuervo A. M., Macian F. (2014) Chaperone-mediated autophagy regulates T cell responses through targeted degradation of negative regulators of T cell activation. Nat. Immunol. 15, 1046–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Hewavitharana T., He L. P., Xu W., Johnstone L. S., Dziadek M. A., Gill D. L. (2006) STIM2 is an inhibitor of STIM1-mediated store-operated Ca2+ entry. Curr. Biol. 16, 1465–1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soboloff J., Spassova M. A., Tang X. D., Hewavitharana T., Xu W., Gill D. L. (2006) Orai1 and STIM reconstitute store-operated calcium channel function. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 20661–20665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peinelt C., Vig M., Koomoa D. L., Beck A., Nadler M. J., Koblan-Huberson M., Lis A., Fleig A., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2006) Amplification of CRAC current by STIM1 and CRACM1 (Orai1). Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 771–773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercer J. C., Dehaven W. I., Smyth J. T., Wedel B., Boyles R. R., Bird G. S., Putney J. W. Jr (2006) Large store-operated calcium selective currents due to co-expression of Orai1 or Orai2 with the intracellular calcium sensor, Stim1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24979–24990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]