Highlights

-

•

Delayed right sided of diaphragm rupture or hernia is a rare.

-

•

Most of the diaphragmatic hernia patients are asymptomatic.

-

•

The main treatment approach is repair of the diaphragmatic hernia defect after reduction of the organs and tissues into the abdominal cavity.

-

•

A dual mesh repair can be used for a large diaphragm hernia.

Keywords: Traumatic diaphragm rupture, Diaphragm hernia, Dual mesh

Abstract

Introduction

Diaphragmatic hernia secondary to traumatic rupture is a rare entity which can occur after stab wound injuries or blunt abdominal traumas. We aimed to report successfully management of dual mesh repair for a large diaphragmatic defect.

Case report

A 66-year-old male was admitted with a right sided diaphragmatic hernia which occurred ten years ago due to a traffic accident. He had abdominal pain with worsened breath. Chest X-ray showed an elevated right diaphragm. Further, thoraco-abdominal computerized tomography detected herniation a part of the liver, gallbladder, stomach, and omentum to the right hemi-thorax. It was decided to diaphragmatic hernia repair. After an extended right subcostal laparotomy, a giant right sided diaphragmatic defect measuring 25 × 15 cm was found in which the liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum were herniated. The abdominal organs were reducted to their normal anatomic position and a dual mesh graft was laid to close the diaphragmatic defect. Patients’ postoperative course was uneventful.

Discussion

Diaphragmatic hernia secondary to trauma is more common on the left side of the diaphragm (left/right = 3/1). A right sided diaphragmatic hernia including liver, stomach, gallbladder and omentum is extremely rare. The main treatment of diaphragmatic hernias is primary repair after reduction of the herniated organs to their anatomical position. However, in the existence of a large hernia defect where primary repair is not possible, a dual mesh should be considered.

Conclusion

A dual mesh repair can be used successfully in extensive large diaphragmatic hernia defects when primary closure could not be achieved.

1. Introduction

Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture (TDR) or diaphragmatic injury is a rare, life-threating clinical condition which usually occurs after thoraco-abdominal blunt or penetrating injuries [1]. The incidence of isolated TDR is 0.2–1.9% [2]. Left sided diaphragmatic rupture occurs from 80 up to 90% after blunt TDRs, whereas right sided diaphragm rupture is less frequently seen. [2]. Combined herniation of the liver, stomach, gallbladder and omentum through the diaphragmatic defect is extremely rare and difficult to recognize [3].

In patients with diaphragmatic hernia, the clinic presentation is related according to herniated organs or tissues and to their occupied volumes in the thorax. Abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, worsened breath and tachycardia are generally present in symptomatic patients. However, some patients are asymptomatic whose diagnosis may be delayed for many years, and herniation into the thorax may increased over time [1], [2], [3]. Blunt traumatic injuries usually presents within months or years in addition with herniation of abdominal organs to the thorax which carry a mortality rate of 30- 60% [4], [5], [6].

The patient’s history, thorax X-Ray, thoraco-abdominal computed tomographies (CT) are useful for diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia [4], [7]. Curative treatment method is primary repair of the diaphragmatic hernia defect. However, there is no consensus for timing of surgery which is usually performed when symptom and signs become obvious [8], [9], [10]. Herein, we present the management of a giant diaphragmatic hernia with dual mesh repair.

2. Case report

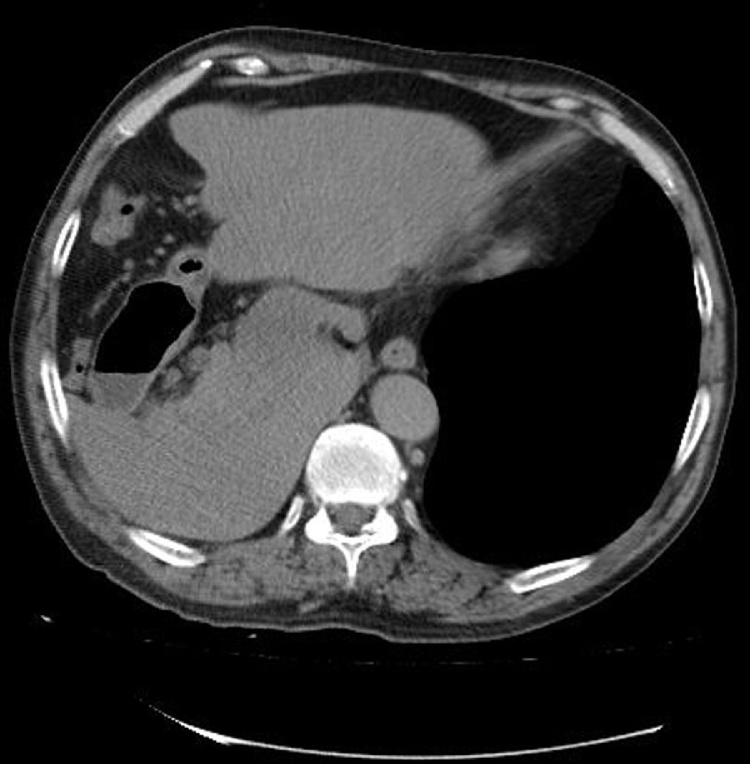

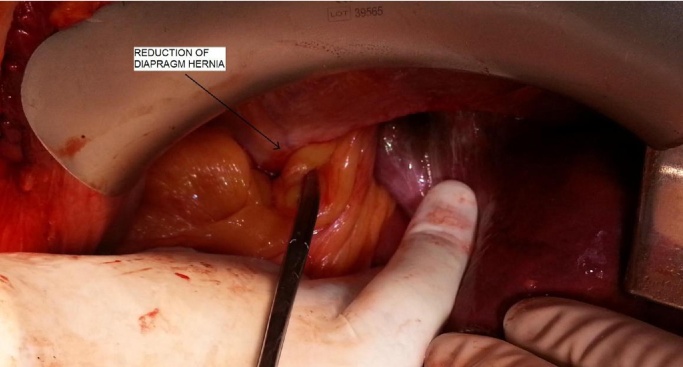

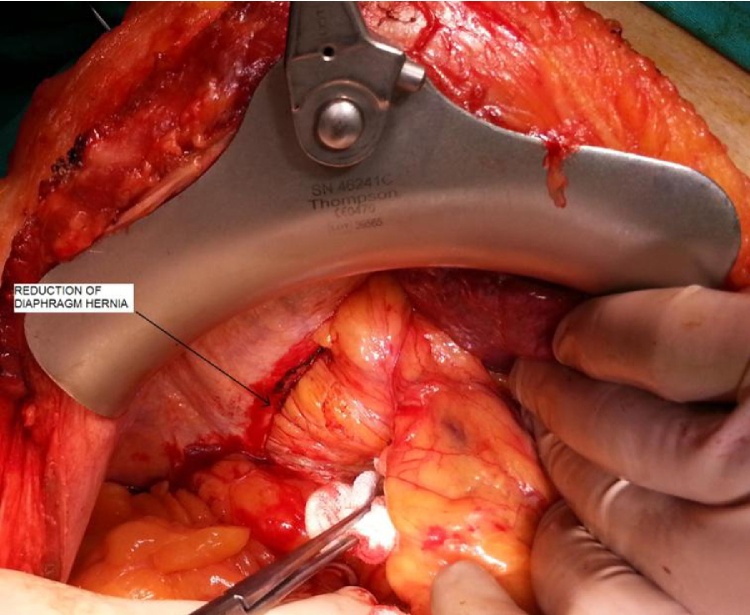

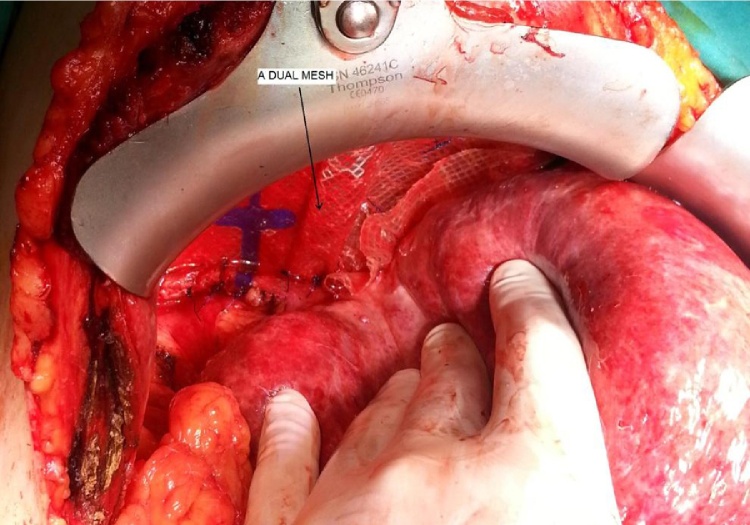

A 66 year-old male patient was admitted for delayed diaphragmatic hernia with complaints of abdominal pain and worsened breath. The patient had a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and a history of blunt trauma more than 10 years duration. On physical examination, the traube area was close and lung sounds were decreased in the right inferior thorax. Chest X-Ray showed an elevated right diaphragm (Fig. 1). Thoraco-abdominal CT detected an elevated right diaphragm due to herniation of liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum. (Fig. 2). The patient underwent surgery with ASA-3 (American society of anesthesia). The abdominal cavity was opened with Makuuchi incision under general anesthesia. During the abdominal exploration, right lobe of the liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum were not in their anatomical position and these organs and tissues extended to the right thorax through the diaphragmatic defect. Diaphragmatic hernia defect was approximately 18 × 15 cm in size (Fig. 3). The herniated right lobe of liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum were relocated to their anatomical position after meticulous dissection of the adhesions (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) Atelectasis of right lobe was gradually opened by giving positive pressure. A dual mesh (Physiomesh, Johnson&Johnson, Ethicon, Germany) was prepared for the extensive diaphragmatic defect which could not be achieved by primary closure. The dual mesh was properly laid to strong diaphragm and it was primary sutured with interrupted 2-0 polypropylene sutures (Fig. 6). A thorax tube was placed after hemostasis. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful with enough expansion in the right lung (Fig. 7). The patient was discharged on the 12th postoperative day. The 3th month follow-up confirmed the healing of the diaphragmatic hernia (Fig. 8). The patient has no initial symptoms and his life satisfaction is good after surgery.

Fig. 1.

Chest X Ray showing an elevated right diaphragm.

Fig. 2.

Herniation of the liver, gallbladder, omentum and stomach in thoracic CT.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperatively reduction of herniated organs.

Fig. 4.

Reduction of herniated organs.

Fig. 5.

Appearance of giant diaphragmatic defect.

Fig. 6.

Repairing of diaphragmatic defect with dual mesh.

Fig. 7.

Appearance of postoperative right diaphragm in chest X-ray.

Fig. 8.

Chest X-ray after postoperative 3 months.

3. Discussion

Diaphragmatic hernia is a herniation of the abdominal organs or tissues to the thoracic cavity [1]. Most of the diaphragmatic hernias (75%) usually occur after blunt or penetrating trauma due to diaphragmatic rupture [1], [2]. TDR is often seen in males and male to female ratio is 4/1 [2]. The incidence of diaphragmatic ruptures after thoraco-abdominal trauma is approximately 0.8 to 5% whereas the incidence of combined liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum herniation is extremely rare [2], [3].

Abdominal organ herniation was first described by Sennertus in an autopsy in 1541. There are a lot of hypothesis about mechanism of delayed presentation of a diaphragmatic rupture. Delayed rupture of a devitalised diaphragmatic muscle may occur several days or weeks after the initial injury so intraperitoneal organs can herniate into the thorax [3], [4]. Rashid et al. have reported that there is commonly a delay period between trauma and diagnosis [4]. Most of the TDRs (80–90%) usually occur in the left diaphragm because, left diaphragm is congenitally weaker than the right diaphragm which is protected by the liver [4], [5]. On the other hand, morbidity and mortality rates of right TDR is much higher. In a review on diaphragmatic rupture including 980 cases carried out by Shah et al. [6], the rate of left-sided diaphragmatic rupture was 68.5%. Right-sided diaphragmatic rupture was seen in 24.2% of cases and bilateral diaphragmatic rupture occurs in 1.5% of the cases. Shah et al. [6] also reported the rate of diaphragmatic rupture as 43.5% during preoperative examination, 41.4% at surgery and 14.6% postoperatively. Liver and omentum are often herniated to the right diaphragm, whereas the left-sided hernias usually contain stomach, spleen, liver, colon and/or omentum [5], [6]. In our patient, combined liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum were herniated to the right diaphragm.

Carter et al. [7] classified the TDRs in three groups: Tip 1 hernia is diagnosed immediately after trauma; type 2 hernia is diagnosed within their recovery period and type 3 is diagnosed when the patient presents with ischemia or perforation signs of the herniated organs. The diagnosis and treatment can be delayed in misdiagnosed patients and diaphragmatic hernia defect can be increased over time. Abdominal organs or tissues can be injured in 80–90% of patients with diaphragmatic rupture and mortality can increase up to 28% [1], [7]. In present study, the diagnosis was received ten years after trauma.

Most of the diaphragmatic hernia patients are asymptomatic. The symptoms and signs are strongly associated with the size of the diaphragmatic defect, herniated organs and the existence of pulmonary disease. Symptomatic patients have abdominal pain, nausea and womiting, worsened breath, chest pain, dyspnea, tachypnea, cough and if strangulation of abdominal organs such as the colon or small bowel exists, abdominal distention and acute abdomen can occur with high morbidity and mortality [3], [4], [8]. Our patient had abdominal pain and breathlessness. Patient’s histories, chest X-Ray are useful for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture or hernia and thoracoabdominal CT and MRI are more sensitive and specific. Chest X-Ray can show an elevated diaphragm with air-filled gastrointestinal tract and thoracoabdominal CT and MRI can detect which herniated organs into the thorax [8], [9].

The main treatment approach is primary repair of the diaphragmatic hernia defect after reduction of the organs and tissues into the abdominal cavity. In hernias with smaller defect, primary repair with non-absorbable sutures is usually sufficient. Laparoscopic approach is often preferred in hemodynamically stabile patients with small diaphragmatic defects. In the study by Küçük et al. [10], 45 patients were treated with abdominal approach whereas 3 patients were treated through thoracotomic approach. In the study by Hacıibrahimoğlu et al. [11], 16 patients underwent primary repair and 2 patients underwent polypropylene mesh repair with a mortality rate of 5.5%. In the study by Rodriquez et al. [12] including 60 cases, the diaphragmatic defect was completely repaired with primary closure via abdominal approach and the mortality rate was 26.7%. In patients with giant diaphragmatic hernias, synthetic or biologic grafts can be used for definitive treatment and prevention of recurrence [5], [9], [13]. Despite limited inflammatory response and minimized adhesion formation of biologic grafts, the recurrence is higher [13]. In the case report by Al-Nour et al. [13], the defect was repaired with biologic mesh (human acellular dermal matrix).

The ideal mesh generates adhesion to the diaphragmatic surface but not the visceral side [14]. Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) prostheses (dual-sided composite mesh) have some of above mentioned features and also PTFE encourages ingrowth of host tissue from the underlying crura, producing local fibrosis and a more uniform mesh-tissue complex. E-PTFE was thought to have a benign behavior as opposed to hollow viscera, with encapsulation of the material and neomesothelialization of the exposed abdominal surface so dual-sided mesh has the merits of prosthetic mesh and may avoid possible major complications [15]. Chilintseva et al. [16] reported the initially results of dual-sided prosthesis for large hiatal hernias repairs, demonstrating satisfactory results. In the literature, dual mesh repair of diaphragmatic hernias without hiatal hernia is reported in a few case reports. In a systematic literature review conducted by Rashid et al., reported a total of 13 right sided diaphragmatic rupture cases. Of these, the liver was herniated in 6 patients into the diaphragmatic area [4], [17]. We present probably the first delayed right sided diaphragmatic hernia in which the liver, stomach, gallbladder and omentum were herniated. Sathyanarayana et al. [17] reported a case with large diaphragmatic hernia that underwent dual mesh repair. Dente et al. [18] reported a symptomatic patient with Bochdalek hernia who was successfully treated laparoscopically using dual mesh. In the present study, the patient had a giant diaphragmatic defect 18 × 15 cm in size with combined herniation of liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum. The diaphragmatic defect was too large which did not allow to primary closure. Diaphragm hernia repair approaches can cause postoperative pneumonia, deep venous throumboembolism, myocardial infarction, or sepsis. In our case, none of these complications occurred.

4. Conclusion

Delayed giant right diaphragmatic hernia including the liver, gallbladder, stomach and omentum is extremely rare. A dual mesh repair may be useful in patients with giant diaphragmatic hernias where primary closure could not be achieved.

Conflicts of interest

This study was not supported by any institution and company. There is not any conflict of interest.

Funding

None.

Author contribution

Metin Ercan: Study design.

Mehmet Aziret: Study design and write page.

Kerem Karaman: Write page.

Birol Bostancı: Data collection.

Musa Akoğlu: Data analyst and interpretation.

Guarantor

Mehmet Aziret.

Acknowledgments

This study was not supported by any institution and company. This study was presented as the oral presentation at 4th National Congress of Gastroenterology Surgery. There is not any conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Symbas P.N., Vlasis S.E., Hatcher C. Blunt and penetrating diaphragmatic injuries with or without herniation of organs in to the chest. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1986;42:158–162. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)60510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chughtai T., Ali S., Sharkey P., Lins M., Rizoli S. Update on managing diaphragmatic rupture in blunt trauma: a review of 208 consecutive cases. Can. J. Surg. 2009 June;52(3):177–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zarzavadjian Le Bian A., Costi R., Smadja C. Delayed right-sided diaphragmatic rupture and laparoscopic repair with mesh fixation. Ann. Thorac. Cardio. Vasc. Surg. 2014;(20 Suppl):550–553. doi: 10.5761/atcs.cr.12.02065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rashid F., Chakrabarty M.M., Singh R., Iftikhar S.Y. A review on delayed presentation of diaphragmatic rupture. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2009;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1749-7922-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antoniou S.A., Pointner R., Granderath F.A., Köckerling F. The Use of Biological Meshes in Diaphragmatic Defects −An Evidence-Based Review of the Literature. Front. Surg. 2015;2:56. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2015.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah R., Sabanathan S., Mearns A.J., Choudhury A.K. Traumatic rupture of diaphragm. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1995;60:1444–1449. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00629-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter B.N., Giuseffi J., Felson B. Traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Am. J. Roentgenol. Radium Ther. 1951;65:56–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nchimi A., Szapiro D., Ghaye B., Willems V., Khamis J., Haquet L. Helical CT of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2005;184:24–30. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.1.01840024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H.W., Wong Y.C., Wang L.J., Fu C.J., Fang J.F., Lin B.C. Computed tomography in left sided and right sided blunt diaphragmatic rupture: experience with 43 patients. Clin. Radiol. 2010;65:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Küçük H.F., Demirhan R., Kurt N., Özyurt Y., Topaloğlu İ., Mustafa Gülmen M. Traumatic diaphragmatic rupture: analysis of 48 cases. Ulus Travma Derg. 2002;8:94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haciibrahimoglu G., Solak O., Olcmen A., Bedirhan M.A., Solmazer N., Gurses A. Management of traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Surg. Today. 2004;34:111–114. doi: 10.1007/s00595-003-2662-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez-Morales G., Rodriguez A., Shatney C.H. Acuterupture of thediaphragm in blunttrauma: analysis of 60 patients. J. Trauma. 1986;26:438–444. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198605000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Nouri O., Hartman B., Freedman R., Thomas C., Esposito T. Diaphragmatic rupture: is management with biological mesh feasible. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2012;3:349–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W., Tang W., Shan C.X., Liu S., Jiang Z.G., Jiang D.Z., Zheng X.M., Qiu M. Dual-sided composite mesh repair of hiatal hernia: our experience and a review of the Chinese literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5528–5533. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i33.5528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frantzides C.T., Carlson M.A., Loizides S., Papafili A., Luu M., Roberts J., Zeni T., Frantzides A. Hiatal hernia repair with mesh: a survey of SAGES members. Surg. Endosc. 2010;24:1017–1024. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0718-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chilintseva N., Brigand C., Meyer C., Rohr S. Laparoscopic prosthetic hiatal reinforcement for large hiatal hernia repair. J. Visc. Surg. 2012;149:e215–e220. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sathyanarayana N., Rao R.M., Rai S.B. An adult recurrent diaphragmatic hernia with a near complete defect: a rare scenario. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2012;6:1574–1576. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4314.2567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dente M., Bagarani M. The laparoscopic dual mesh repair of a diaphragmatic hernia of Bochdalek in a symptomatic elderly patient. Updates Surg. 2010;62:125–128. doi: 10.1007/s13304-010-0022-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]