Abstract

Objective

Korean American Elderly (KAE) have high rates of depression but underuse mental health services. The purpose of this study was to assess the meaning of depression and help seeking among KAE residing in the United States who have clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Methods

As a follow up to the Memory and Aging Study of Koreans (MASK; n=1,118), a descriptive epidemiological study which showed that only one in four of KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9≥10) used mental health services, we conducted a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms regarding the meaning of depression and beliefs about help seeking. Ten participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms were approached and 8 were recruited for semi-structured interviews.

Results

KAE did not identify themselves as depressed though experiencing clinically significant depressive symptoms. They associated depression with social discrimination, social isolation, and suicide in the extreme circumstance. They attributed depression to not achieving social and material success in America and strained relationships with their children. Participants attempted to self-manage distress without telling others in their social network. However, KAE were willing to consult with mental health professionals if the services were bilingual, affordable, and confidential.

Conclusion

KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms are a vulnerable group with need and desire for linguistically and culturally relevant mental health services who are isolated due to a complex array of psychological and social factors.

Keywords: Depression, Korean older adults, Help seeking, Qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

The number of Asian American and Pacific Islander older adults in the United States is projected to increase from 1.3 million in 2008 to 7.6 million in 2050.1 Over 90% of Asian American older adults are foreign born and 80% of them speak languages other than English at home.2 Over 70% of the Korean American Elderly (KAE) have limited English proficiency despite living in the United States an average of 21 years,3 and over a quarter do not have health insurance.4

The prevalence of depression among KAE is as high as 40%.5 The California Health Interview Survey revealed that KAE had the highest psychological distress among Asian American subethnic groups, possibly due to acculturation factors associated with recent immigration history.6 Despite high prevalence of depression, KAE were least likely to seek help from primary care providers or to receive psychotropic medications compared to older adults of other Asian subgroups.7

Effective strategies to improve access and engagement of immigrant elderly groups in existing mental health services are not well developed. Studies of depression and help seeking among KAE have primarily used quantitative instruments to measure levels of psychological distress and low service use.8,9 Though informative, quantitative investigation alone has not offered meaningful insights as to how KAE conceptualize and experience depression.

Understanding the explanatory model of illness–what a person calls the problem, causes and prognosis of the condition, and fears about proposed treatment–is necessary to develop mental health services that are tailored and relevant to a targeted group's needs.10 Mixed methods that integrate both quantitative and qualitative approaches are better suited than quantitative approaches alone to understand KAE's point of view on depression to inform appropriate design of mental health treatments.11

This study qualitatively followed up Korean older adults who were quantitatively identified as having clinical depressive symptoms. The purpose of this study was to understand the lived experience of Korean older adults in their motivations or patterns of using professional mental health services. Using qualitative methods, participants responded to open-ended questions to express how they conceptualized depression and professional mental health services. The nature of this qualitative study was inductive rather than deductive, and this study did not have a hypothesis to test.

METHODS

Participant recruitment

The Memory and Aging Study of Koreans (MASK) was a descriptive epidemiological study that assessed the prevalence of and factors associated with dementia and major depression among KAE and mental health service use.9 The sample consisted of 1,118 first-generation Korean Americans aged 60 years and older recruited between 2010 and 2012 from Korean churches, senior housing, senior centers, adult day care centers, and social service organizations. Only those who could speak Korean fluently were recruited. A total of 1,116 MASK participants were analyzed, after excluding data on two participants due to incomplete records. The mean age of the sample was 70.5 years [standard deviation (SD): ±7 years]. The MASK study found a high proportion of Korean older adults with clinically significant depressive symptoms (PHQ-9K ≥10) in the community (n=120; 10.8%), but only 24.2% (n=29) with clinically significant depressive symptoms accessed professional mental health treatment.12 All study procedure was approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board, and all participants underwent a written informed consent process.

Measurement strategy

Trained bilingual registered nurses and community mental health workers administered the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9K) to KAE (Supplementary 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). Each community health worker was a college graduate and was trained to administer the PHQ-9 and the MMSE-KC by a board-certified, bilingual Korean-American psychiatrist based on the manuals. The PHQ-9K has well-established validity and reliability among Korean older adults in Korea and the United States.13,14 Scoring of the PHQ-9K range from 0 to 27 points. PHQ-9 scores are usually interpreted as 0–4=no or minimal depression; 5–9= mild depression; 10 or above=moderate to severe or clinically significant depression.15 The PHQ-9K showed good test-retest reliability (r=0.60), and internal consistency (Cronbach α=0.88), and convergent validity with the GDS (r=0.74) and the CES-D (r=0.66) among older adults in Korea.14 Internal consistency of the PHQ-9K was high among KAE in the United States (Cronbach α=0.92).13 The Korean translation of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-KC) assessed cognitive impairment.16 Sociodemographic data included age, sex, education, and years lived in the United States.

Purposive sampling

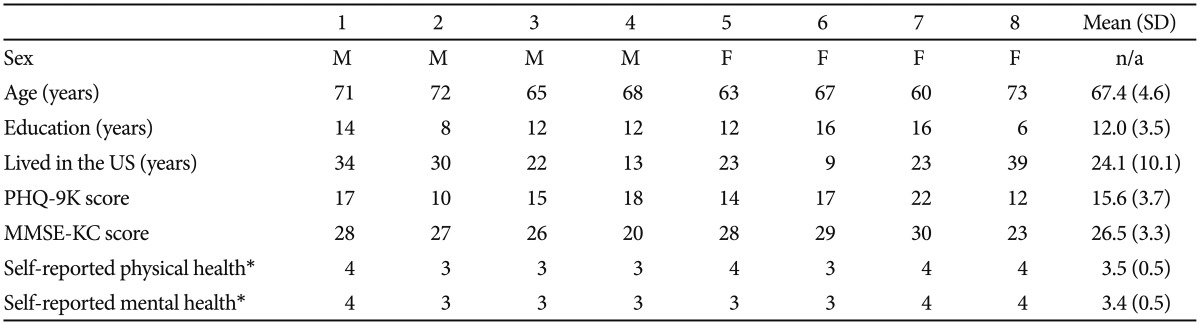

For qualitative interviews for this study, purposive sampling was used to sample participants from MASK study with clinically significant depressive symptom scores as measured by the PHQ-9K (Table 1). The intention was to obtain knowledgeable perspective on the meaning of depression and barriers to service among KAE with most significant clinical need for depression treatment.17 The goal of this type of qualitative research is not generalizability or representativeness of the study findings, but rather understanding of contextualized and lived experiences of KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms. Thirty men and ninety women out (n=120) of a 1,116 church-based sample of KAE in MASK had clinically significant depressive symptoms.12

Table 1. Characteristics of sample completing semi-structured interviews.

*self-reported physical and mental health were rated, 1. Excellent, 2. Good, 3. Fair, 4. Poor. PHQ-9K: Patient Health Questionnaire-9, Korean version, MMSE-KC: Mini-Mental State Examination, Korean version, SD: standard deviation

Semi-structured interviews

The semi-structured interview guide was modified and translated from a study of depression in late life.18,19 The interview protocol consisted of: 1) open-ended questions about immigration experiences and social support; 2) vignettes that described individuals with depressive symptoms without using the word 'depression,' followed by questions asking what the individuals' problems were, what could be done, and who could help; and 3) questions about the meaning of depression and barriers to receiving professional mental health services (Supplementary 2 in the online-only Data Supplement).

Interview procedure

A bilingual public mental health researcher (SL) with prior work in psychiatric rehabilitation therapy conducted all interviews in Korean between May and December, 2011. Each interview lasted 1.5 to 2 hours. Three Korean-speaking research staff transcribed audio-recorded interviews verbatim in Korean.

Analytic strategy

We used Stata 11.0/SE to compute the means and standard deviations of participant demographic and clinical characteristics. The interview texts transcribed in Korean were transferred into Atlas.ti (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany) for coding and visual depiction of the interrelationships between codes in Korean. Codes and themes emerged based on close readings of the transcribed texts in Korean, using a constant comparative method.20 The constant comparative method is a form of grounded theory that combines the qualitative analysis method of systematically coding to test a particular set of hypotheses and the tradition of constantly redesigning and reintegrating codes and themes for theory generation.21 The constant comparative method was appropriate for theory generation on perceived causes of depression and barriers to mental health service use based on KAE's open-ended responses. We conducted all qualitative analyses in Korean. We translated quotations selected for this article into English. A transdisciplinary group consisted of six bilingual (Korean/English) researchers from the fields of public health, geriatric psychiatry, nursing, and internal medicine met regularly to check the codes and to discuss emerging themes. We discussed divergent views on data interpretation until consensus was reached.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

We contacted 10 KAE in the MASK study starting with the highest score of depressive symptoms, among those with a PHQ-9K score at or above 10 with the goal of having both men and women represented.15 Two individuals refused to participate due to lack of interest (80% response rate). Table 1 displays demographic, clinical, and mental health service use data of 8 study participants. The mean age was 67 (SD: 4.6), mean PHQ-9K score was 15.6 (SD: 3.7), and mean MMSE-KC score was 26.4 (SD: 3.3).

Emergent themes

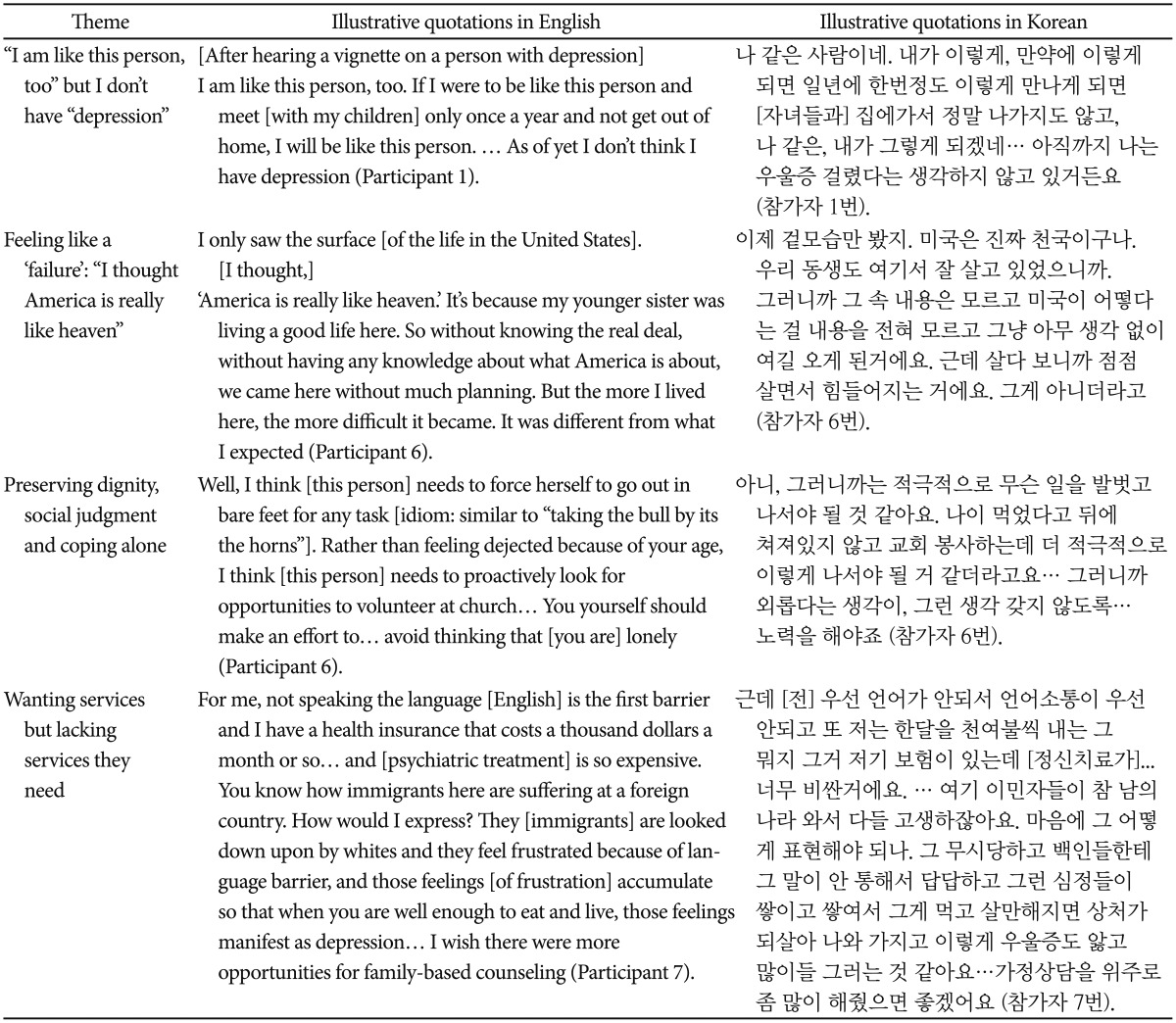

In Table 2 described four themes that emerged in this study regarding meaning of depression and help seeking. First, KAE had a fragmented knowledge of depression, and despite personal experience with treatment by some, did not identify with the diagnosis. Second, failures of immigrant experiences and low self-esteem were significantly tied to depression. Third, social pressures silenced distress and resulted in social isolation. Finally, participants desired services, but had few options for culturally competent mental health services.

Table 2. Themes with corresponding quotes from Korean American elderly regarding meaning of depression and help seeking.

"I am like this person, too" but I don't have "depression"

Participants had experiential knowledge of depression. They believed that accumulation of stressors, such as death of a spouse or serious physical ailment could trigger the development of depression. Some said that depression "우울증" (used in a medical context) meant being sensitive to interpersonal stress and that improved communication with and support from family could lead to recovery. Participant 1 (71 year old man) and participant 6 (67 year old woman), who were under extreme financial pressure, believed that depression would disappear with financial stability. Participants associated depression with not enjoying activities they used to enjoy and having little energy.

Alongside experiential knowledge, all participants had rudimentary medical knowledge of depression and believed that "depression" was "an illness," that it meant "you are a patient" and "you need to get medications." Participants viewed depression as occurring on a continuum from mild to severe symptoms, and six participants mentioned that suicide is the extreme consequence of depression.

Six participants read the vignette of a depressed person and said, "I am like this person, too" but they did not identify with having a depression diagnosis even though three participants received treatment. Rather, they reported having "something like depression" that is less serious in nature. Participant 2 (72 year old man) who was clinically depressed and receiving medical treatment said, "If a doctor tells me now, "You have depression," then I would be shocked" because people with depression have a far more serious condition. Most participants perceived the consequences of receiving a depression diagnosis in catastrophic terms. Participant 1 (71 year old man) said the consequences of depression are, "Very terrible all around... as if everything is being destroyed, in relation to people around you–family, finances, everything."

Three participants were taking medications for depression and one had used psychotherapy, but only one person who received psychotherapy admitted that she had depression. One participant was told by her physician that antidepressants were for improving urination. Two participants said that antidepressants only have beneficial effect on sleep. Despite some participants having received treatment for depression, the participants had a rudimentary understanding of clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Feeling like a 'failure': "I thought America is really like heaven"

Despite decades of living in the United States, participants' views of themselves were rooted in their identity as 'failed' immigrants, which they strongly associated with depressive symptoms. Every participant described having had big hopes and dreams for their life in the United States, yet they realized that day-to-day realities did not match their expectations. A 67 year old woman described her disappointment upon realizing that America was not the land of opportunity as she imagined it to be.

Participant 6 (67 year old woman): ... I only saw the surface [of the life in the United States]. [I thought,] 'America is really like heaven.' It's because my younger sister was living a good life here. So without knowing the real deal, without having any knowledge about what America is about, we came here without much planning. But the more I lived here, the more difficult it became. It was different from what I expected.

In addition to participants' personal sense of failure was the need to keep up appearances for their families in Korea. Families and relatives of participants in South Korea expected Korean immigrants to the United States to be financially and socially successful. As a result, participants were reluctant to share their acculturation stressors with their support network in Korea.

Participants expressed feeling vulnerable in multiple ways and were fearful of exposing their low educational status, limited English proficiency, and poor computer skills to their children. Some participants felt hurt when their children and relatives rejected their request for financial help, home repair, computer-related assistance, or grocery shopping in times of sickness. Participants found it stressful to communicate in English to resolve day-to-day problems, and felt judged and demeaned by their children and relatives when they asked for help.

Participants described differences in family values between their children and them, leading to feelings of being disrespected and not valued. Participants blamed themselves for their children's disrespectful behaviors towards them. Participants felt that they had placed more importance in caring for their own parents than prioritizing the care of their children which led to distant relationships. Participants believed that had they cultivated better relationships with their children, it would have resulted in more respect and gratitude by their children in their [participants'] old age.

Participant 1 (71 year old man): I am not a learned person. And I only learned a little bit, so... I can't even spell the first alphabet of 'computer' [figurative speech] and I'm trying to learn it. Phew, the closest person to me is my son, but I think in my head, 'I won't learn from you. If I were to have money, I'd pay someone else to learn, but I won't ever learn from you.' ... Other older adults know how to use the computer but I am afraid that I am not smart enough, and I feel ashamed.

Preserving dignity, social judgment and coping alone

In the face of multiple perceived failures, participants described strong feelings of being judged and they coped by pretending to be well and able to take care of matters without receiving help. They described distancing themselves from others as they found few options for comfort and security from Korean-speaking communities to which they belonged. KAE said that they would rather not share their illness or pain for fear of being subjected to gossip or humiliation. Participant 1 (71 year old man) noted, "I realized that people look down upon you when you tell them about your pain/illness. I will never tell others, even when I am in pain, but say, 'Oh, I'm fine. Oh, I'm not sick anywhere.'" Likewise, participant 7 (60 year old woman) confided that her husband was a well-known businessman in the Korean American community, and that she chose not to contact others in her social circles concerning her emotional distress in fear of marring her husband's reputation. Participants were not willing to seek support from informal network concerning their deep emotional wounds.

KAE expressed not telling anyone about their mental distress and attempting to take care of emotional distress by making efforts alone. Instead of seeking help from their informal network, most participants said that persons experiencing distress should make an effort to manage their own distressful situations. In response to a vignette describing a person with depression, participant 6 (67 year old woman) expressed that one should proactively make an effort to overcome feeling down or to fight loneliness, such as volunteering at church. She said it is one's responsibility to engage in conversations with one's family members to avoid feeling lonely.

Participant 6 (67 year old woman): Well, I think [this person] needs to force herself to go out in bare feet for any task [idiom: similar to "taking the bull by the horns"]. Rather than feeling dejected because of your age, I think [this person] needs to proactively look for opportunities to volunteer at church... You yourself should make an effort to... avoid thinking that [you are] lonely.

This approach of self-managing emotional distress appeared to be a response to having few options for professional, bilingual, and affordable mental health treatment and lack of social support. They felt a tremendous sense of responsibility to care for oneself without outside help, but were challenged by lack of motivation and resources to do it alone.

Wanting services but lacking services they need

Most participants viewed medications as the last resort, appropriate only when conditions deteriorated to such a degree that their own efforts or counseling could not resolve the problem. They preferred talking to a professional; however, the majority of participants did not know what constituted psychological counseling or where to seek help from bilingual mental health professional. Practical barriers to receiving professional mental health treatment that participants mentioned included limited language proficiency, lack of health insurance, high cost of mental health treatment, and lack of bilingual and professional counselors. Two participants who were undocumented immigrants thought it was unimaginable to receive any medical help due to their undocumented status and lack of health insurance. Participants with undocumented status expressed difficulty in seeking help for their distress from anyone, fearing that others would discover their undocumented status and the possibility of deportation.

Despite formidable barriers, participants were not against seeking professional help. If they were to seek professional help, KAE emphasized the need to talk to a mental health practitioner with extensive training in mental health who provided bilingual and affordable treatment services. Participants stated vaguely that professionalism meant someone with years of specialized mental health or psychology training without being able to specify which types of education or credentials were needed. A few participants were supportive of the idea of seeking help from lay church leaders with some level of psychology training. Most participants had a special respect towards pastors, yet they feared that rumors about their mental health status would spread to their friends and church members.

Participant 2 (72 year old man): In my opinion, counseling should be done by someone with a great deal of... knowledge and experience as well as professionalism. If you were to receive counseling with just about anyone then one might actually get hurt, don't you think?

Participants were doubtful of the quality of lay workers' mental health counseling and their promise to protect confidentiality. They were wary of unintended consequences of consulting with counselors without professional training.

All participants were eager to consult with a mental health professional when given a chance, but they were skeptical about the helpfulness of lay community members. Participant 7 (60 year old woman) had received psychotherapy and participated in a church training program for counseling open to lay church members. After being part of church-based counselor training program for six months, participant 7 doubted the effectiveness of lay counselors helping others, saying, "I think it is dangerous that when someone with low qualification at church counsels others. I studied [as part of the church training for mental health counseling], too, but people without qualification were there, and I felt that they were there mostly to look good to the pastor. I didn't learn anything during a year of training, so how can you expect them to be a counselor after six months of training?"

DISCUSSION

Using a mixed methods approach, our study explored the meaning of depression, its associated stressors, and coping styles among KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms. Our study described a subset of KAE from a quantitative epidemiological study who were at high risk of depression due to multiple factors related to their specific life experience as immigrants yet who had little resources to obtain help. They coped alone, and unlike the usual view of immigrant elderly, participants in our study expressed desire for mental health services if tailored to their needs. We discuss below the relevance of our findings for improving mental health services for this needy, yet underserved group.

KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms have a rich experiential understanding of depression integrated with a rudimentary medical understanding which may not go far enough to actively seek professional help. Despite taking medications for depression, the majority of participants lacked information about depression diagnosis and the reasons for treatment, suggesting the lack of physician-patient communication surrounding mental illness. Identifying with an illness is not an easy matter. Diagnosis is often experienced as a negative and moral judgment and requires redefinition of one's self and one's relation to others. Physicians often lack this perspective as they focus on diagnosis and treatment with less attention paid to patient-centered views that have an impact on treatment adherence and clinical outcomes.

Immigrant Korean elderly are a vulnerable group. The importance of the immigrant experience is undeniable in this group who, despite having resided in the United States for many years, focus on the failure of their immigrant dreams as the defining element in their lives. In our study, participants described feelings of failure, vulnerability and shame with a concomitant need for dignity and respect particularly from their children. Participants often felt that they had nowhere to turn to within their family, the Korean community, nor within the larger American community. Roles of KAE with limited English language ability are confined to Korean-speaking social networks where the fear of damaging reputations is great so that KAE are not willing to admit having problems or seek support. They may be unable to share stressors with their friends and families in Korea due to social pressures. Within their families in the United States, communication and mismatched cultural values may make relations with their children difficult and expression of emotional distress unlikely. The picture is one of social isolation and limited avenues for help seeking. In such a context of personal and social response to emotional distress, although Asians in general are thought to be healthier than their counterparts of other ethnicities in the United States, the social norms that exist to hide emotional distress make detection more difficult by health providers.22

Coping methods among KAE include self-reliance and religious belief. Participants believed strongly on relying on oneself rather than seeking help from others. Although self-reliance can be looked upon as a position of strength, there is also the sense that self-reliance may be the only choice for KAE. Korean churches provide important social and religious services for KAE, and research regarding the usefulness of involvement of religious communities and pastoral counseling have received attention; however, the discriminatory social environment even in faith-based settings may not facilitate help seeking for emotional problems.23

While KAE were not willing to talk about mental distress within their informal social networks, all participants were receptive of the idea of receiving counseling from a bilingual mental health professional if available and affordable. They expressed desire for professional counseling but were aware of the dearth of Korean-speaking mental health professionals in the United States to meet this need. Older adults with limited English proficiency report difficulty following instructions at health care settings, which hindered their engagement in medical care.24 KAE with clinically significant depressive symptoms were not open to receiving group-based therapy with people they do not know, but they preferred an individual treatment with commitment to keep confidentiality. While KAE emphasized the importance of seeking care from a 'professional' counselor with years of mental health training, participants appeared to be amenable to receiving care from case managers, social workers, and nurses with some level of psychiatric training. Recruiting bilingual professionals with the highest level of psychiatry or clinical psychology training for the care of KAE is challenging, although the need for bilingual mental health providers is critical for those not proficient in English because lack of English fluency can effectively block access. Both education regarding counseling services for immigrant elderly and a collaborative care model with active support from case managers may be needed to make services for minority elderly feasible in terms of cost-effectiveness.

Previous literature also showed that KAE were less likely to seek help from professional mental health services despite having higher level of mental distress compared to whites and other Asian subethnic groups.7 KAE appear to hold greater level of misconception about mental health, believing that seeking help for mental health is a sign of weakness and would bring shame to the family.25 Asian Americans, compared whites, reported greater level of shame and embarrassment of having mental illness and had greater difficulty seeking and accessing mental health services.26 Innovative approaches to integrate mental health treatment elements to non-traditional venues would be necessary to veer away from KAE's shame and fear attached to mental illness. As first-generation immigrants with limited English proficiency, KAE were especially in need of problem solving day-to-day tasks. They were in dire need of learning how to speak English, how to use a computer or a cell phone, how to refill a prescription, and how to fix their house. Since their children were not practically or emotionally available, county- or state-level programs to meet educational needs among KAE while integrating mental health screening, education, and referral have potential to reduce gaps in access to mental health care.

One of the strengths of this study is targeted selection of depressed KAE as part of the largest epidemiological study of Korean American older adults in the United States. We were able to qualitatively follow up KAE who have indicated need for mental health services yet have not received them. We obtained the insider's view of depression from those who were assessed with the PHQ-9 and suffering from depressive symptoms. An important strength derives from the ability to carry out interviews and interpretation in Korean without translation because the investigators included native Korean speakers. Limitations of this study include possible selection of healthier and more socially connected KAE who attended Korean ethnic centers that served as sampling units, which would not represent the full range of depressive severity and willingness to seek treatment. Though themes presented in this study were repeatedly mentioned and strong across participants, due to heterogeneity of individual immigration history, and cognitive and mental characteristics, the content of participants' interviews might have been less cohesive. For instance, there were challenges in sustaining focused conversations with participants with more pronounced dementia. It is possible that KAE chose to partially withhold their thoughts, feelings, and experiences because of the interviewer's female sex, younger age, and higher educational status. However, most participants verbally affirmed the interviewer for being comfortable and warm for holding conversations, and asserted that they spoke more openly and candidly than usual.

The next steps for research include development of tailored interventions which take account of the history and life experience of this group of immigrant elderly to provide mental health services which are culturally competent and engaging. Improved screening of depression and culturally-appropriate education regarding depression have the potential to modify Asian American patients' conceptualization of illness and decrease the barriers to receiving professional mental health services.27 Although we focused on traditional mental health services such as counseling and medications in the study, integration of wellness beliefs and self-care behaviors that integrate values and behaviors28 which are specific to KAE may be more effective. Elderly generally say they prefer counseling, and development of services provided in Korean to discuss acculturation stress and intergenerational relationship is ideal. The barriers in terms of resources and cost are significant; disparities and poorer health among minority groups are likely to persist if not addressed.

Acknowledgments

This paper was partially supported by an Alzheimer's Association Investigator-Initiated grant and Sommer Scholars Program research fund. We thank our community partner, Korean Resource Center, Ellicott City, MD and Dr. Miyong Kim for providing community linkage for this study. We thank Dong-Ho Kang, Jung-Hwa Hong, and SooKyung Son for their transcription of participant interviews.

Supplementary Materials

1a. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in English

1b. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Korean

Semi-structured interview guide in English (Korean version available upon request)

References

- 1.Administration on Aging. A Statistical Profile of Asian Older Americans Aged 65 and Older. Washington, DC: Publisher; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruggles SJ, Alexander T, Genadek K, Goeken R, Schroeder MB, Sobek M. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 5.0 [Online] 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. Race Reporting for the Asian Population by Selected Categories: 2010. Suiteland, MD: American Fact Finder; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jang Y, Kim G, Chiriboga DA. Health, healthcare utilization, and satisfaction with service: barriers and facilitators for older Korean Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1613–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sin MK, Choe MA, Kim J, Chae YR, Jeon MY. Depressive symptoms in community-dwelling elderly Korean immigrants and elderly Koreans: cross-cultural comparison. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3:262–269. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20100108-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim G, Chiriboga DA, Jang Y, Lee S, Huang CH, Parmelee P. Health status of older Asian Americans in California. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:2003–2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sorkin D, Nguyen H, Ngo-Metzger Q. Assessing the mental health needs and barriers to care among a diverse sample of Asian American older adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:595–602. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1612-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jang Y, Kim G, Hansen L, Chiriboga DA. Attitudes of older Korean Americans toward mental health services. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:616–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01125.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HB, Han HR, Huh BY, Kim KB, Kim MT. Mental health service utilization among Korean elders in Korean churches: preliminary findings from the Memory and Aging Study of Koreans in Maryland (MASK-MD) Aging Mental Health. 2014;18:102–109. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.814099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman A. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition. New York: Basic Books; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. CA: SAGE Publication Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim MT, Kim KB, Han HR, Huh B, Nguyen T, Lee HB. Prevalence and predictors of depression in Korean American elderly: findings from the Memory and Aging Study of Koreans (MASK) Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnelly PL, Kim KS. The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9K) to screen for depressive disorders among immigrant Korean American elderly. J Cult Divers. 2008;15:24–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han C, Jo SA, Kwak JH, Pae CU, Steffens D, Jo I, et al. Validation of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Korean version in the elderly population: the Ansan Geriatric study. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49:218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JH, Lee KU, Lee DY, Kim KW, Jhoo JH, Kim JH, et al. Development of the Korean Version of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Packet (CERAD-K) J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2002;57:P47–P53. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.1.p47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mix Methods Res. 2007;1:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barg FK, Huss-Ashmore R, Wittink MN, Murray GF, Bogner HR, Gallo JJ. A mixed-methods approach to understand loneliness and depression in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S329–S339. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.6.s329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallo JJ, Bogner HR, Straton JB, Margo K, Lesho P, Rabins PV, et al. Patient characteristics associated with participation in a practice-based study of depression in late life: the spectrum study. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2005;35:41–57. doi: 10.2190/K5B6-DD8E-TH1R-8GPT. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Problems. 1965;12:436–445. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. New York: Aldine Publishing; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen MS, Jr, Hawks BL. A debunking of the myth of healthy Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. Am J Health Promot. 1995;9:261–268. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-9.4.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamada AM, Lee KK, Kim MA. Community mental health allies: referral behavior among Asian American immigrant Christian clergy. Community Ment Health J. 2012;48:107–113. doi: 10.1007/s10597-011-9386-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim G, Worley CB, Allen RS, Vinson L, Crowther MR, Parmelee P, et al. Vulnerability of older Latino and Asian immigrants with limited English proficiency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03483.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang Y, Chiriboga DA, Okazaki S. Attitudes toward mental health services: age-group differences in Korean American adults. Aging Ment Health. 2009;13:127–134. doi: 10.1080/13607860802591070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jimenez DE, Bartels SJ, Cardenas V, Alegría M. Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among racial/ethnic older adults in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28:1061–1068. doi: 10.1002/gps.3928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeung A, Chang D, Gresham RL, Jr, Nierenberg AA, Fava M. Illness beliefs of depressed Chinese American patients in primary care. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:324–327. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120892.96624.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kagawa-Singer M, Chung RCY. A paradigm for culturally based care in ethnic minority populations. J Commumity Psychol. 1994;22:192–208. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

1a. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in English

1b. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 in Korean

Semi-structured interview guide in English (Korean version available upon request)