Abstract

B cells lymphoma is one of the most challenging extra-hepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus (HCV). Recently, a new kind of B-cell lymphoma, named double-hit B (DHL), was characterized with an aggressive clinical course whereas a potential association with HCV was not investigated. The new antiviral direct agents (DAAs) against HCV are effective and curative in the majority of HCV infections. We report the first case, to our knowledge, of DHL and HCV-infection successfully treated by new DAAs. According to our experience, a DHL must be suspected in case of HCV-related lymphoma, and an early diagnosis could direct towards a different hematological management because a worse prognosis might be expected. A possible effect of DAAs on DHL regression should be investigated, but eradicating HCV would avoid life-threatening reactivation of viral hepatitis during pharmacological immunosuppression in onco-haematological diseases.

Keywords: Hepatitis C, Lymphoma, Direct antiviral agents, Double hit lymphoma, Chronic hepatitis C

Core tip: B cells lymphoma is one of the most challenging extra-hepatic manifestations of hepatitis C virus. Recently, a new kind of B-cell lymphoma, named Double-hit B, was characterized with an aggressive clinical course. This is the first case described in literature of double hit lymphoma with co-existing chronic hepatitis C, successfully treated by new direct antiviral therapies. This case suggests a potential favorable effect of the new antiviral therapies on double hit lymphoma regression.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a major global public health problem, although the newest and most effective antiviral therapies (AVTs), free from severe side effects related to interferon (IFN), are spreading in developed countries. This could lead in the next future to a lower prevalence of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) and of its extra-hepatic manifestations. Among these, the hematologic manifestations are the most challenging. Indeed, HCV could induce B cell proliferation and cause mixed cryoglobulinaemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL)[1]. The typical HCV-related lymphomas are marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) and diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL)[2]. The first could benefit from AVTs, whereas the second group needs more aggressive chemotherapies and the only AVTs seem to be ineffective. More recently, a new kind of lymphoma named double-hit B cell (DHL) was described, characterized by chromosomal rearrangements, specifically of Myc oncogene and either B cell lymphoma 2 and B cell lymphoma 6 oncogenes (Bcl2-Bcl6) or gene for Cyclin D1 (Ccnd1)[3,4]. DHL represents about 5% of all cases of DLBCL and affected patients generally have an aggressive clinical course with poor prognosis, despite combination chemotherapy, with a median overall survival of less than 1-2 years. To date, due to the limited literature concerning this type of lymphoma, the specific treatment is still not clear. A potential correlation between HCV and DHL has never been investigated.

We describe the first case, to our knowledge, of a patient affected by DHL and CHC who underwent a successful antiviral treatment with IFN-free therapy (ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir and dasabuvir).

CASE REPORT

The patient was a 39-year-old Caucasian woman, who tested HCV positive in 2013 during a routine medical evaluation. She had not history of blood transfusions or other risk factors for hepatitis virus transmission. The CHC was sustained by genotype 1b virus, with low necro-inflammatory activity and mild liver fibrosis according to non-invasive evaluation performed by Fibroscan® (4.5 kPa), whereas HCV showed a high replication rate (4500000 UI/mL, Cobas AmpliPrep/Cobas TaqMan®-Roche, Rotkreuz, Switzerland). Ultrasound scans of the liver did not demonstrate signs of fibrosis or spleen enlargement secondary to portal hypertension. Of interest, the patient reported a previous episode of major depression occurred in 2006 and, since then, she had been taking venlafazine 75 mg/d.

In July 2013, due to the enlargement of neck lymph nodes, the patient underwent a hematological evaluation and a lymph node biopsy, and she was finally diagnosed with DLBCL (CD20+, CD30-, Bcl2+, Ki67 50%, Bcl6 + 25%, negativity for CD10 and Mum1), with involvement of nodes on both sides of the diaphragm, bone marrow and spleen (Figure 1). Treatment with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone plus Rituximab (R) (R-CHOP regimen) plus prophylactic intrathecal injection of methotrexate and prednisone, was started. In December 2013, i.e., after six courses of R-CHOP, the patient showed a complete remission of lymphoma according both to Contrast Tomography plus Positron Emission Tomography scans and to bone marrow biopsy. Two additional doses of R were prescribed and, at that time, blood tests showed normal levels of transaminases, while HCV replication did not show any substantial changes (Figure 2). In the following months, the patient was referred to our Liver Unit and she was evaluated for AVT. However, since “all-oral” AVTs for CHC was at that time unavailable in Italy, the patient was evaluated for IFN-based AVT, but she presented relative and absolute contraindications to IFN use, such as a previous episode of major depression, mild anemia, leucopenia (i.e., Haemoglobin 10.7 g/dL, White cells counts 1.980 cells/mm3), as well as to ribavirin (RBV) use (anemia). We therefore asked our case to be evaluated for the expanded access program (EAP) which was ongoing with Paritaprevir (PTV), a NS3/4A protease inhibitor co-formulated with NS5A inhibitor Ombitasvir (OBV) and the pharmacokinetic enhancer ritonavir (r), plus non-nucleoside polymerase inhibitor Dasabuvir (DSV). Since lymphoma is a possible extra-hepatic manifestation of HCV, the pharmaceutical industry committee accepted our patient for participation to the EAP. Unfortunately, in October 2014, the patient experienced the first relapse of lymphoma at the right maxillary sinus (Figure 3), whereas bilateral bone biopsies were negative. Since chemotherapy was urgent, cisplatin, cytarabin, dexamethasone plus R (R-DHAP regimen) were started. After the second cycle of R-DHAP, liver tests worsened, with a rapid evolution to liver failure, i.e., jaundice and ascites (Figure 2). She was admitted to our Unit and the liver decompensation was successfully treated with diuretics and anti-oxidant infusion (glutathione 2 g/d until recovery).

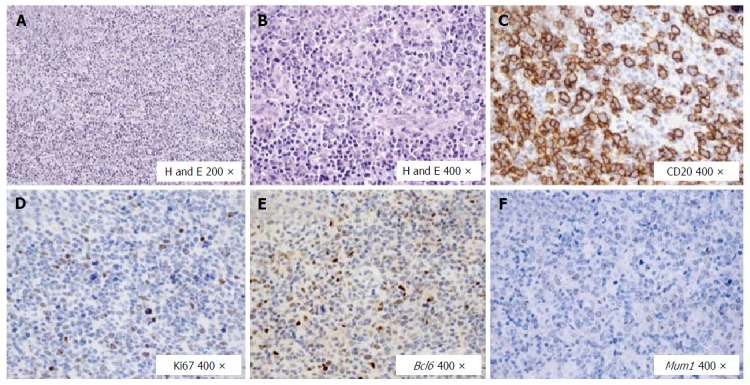

Figure 1.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of the diffuse large B cell lymphoma at the primary diagnosis. A: In the lymph node a polymorphic lymphoid population is seen; B: Large lymphoid cells prevailed; C: These large cells were B CD20+; D: The proliferation rate marked by Ki67 was around 20% with respect to the overall population, but about 40% if compared with the blastic B cell population; E: The large B cells expressed mainly the germinal center marker Bcl6; F: Mum1 was not found expressed at the primary diagnosis. DLBCL: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma; H and E: Hematoxylin and eosin; CD: Clusters of differentiation; Ki67: Cellular marker for proliferation; Bcl6: B cell lymphoma 6; Mum1: Multiple myeloma oncogene 1.

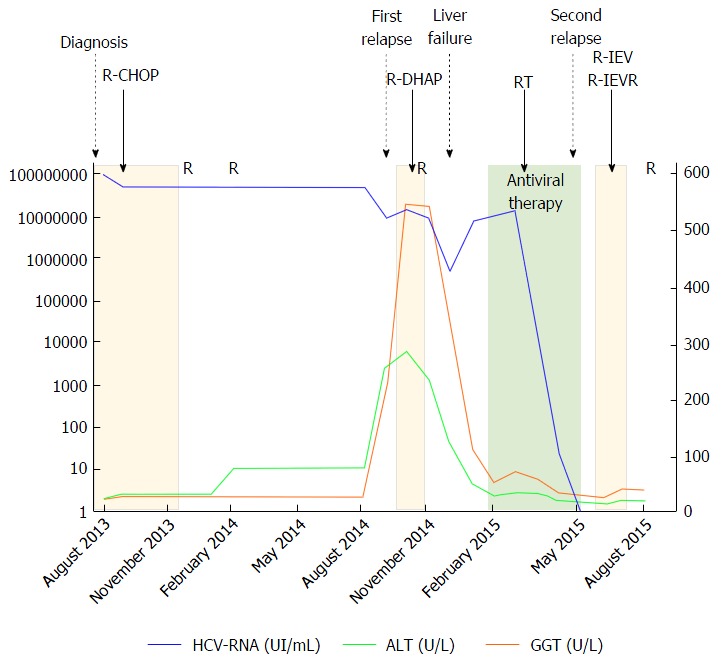

Figure 2.

This figure shows the trends of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alanine amino-transferase and hepatitis C viremia - RNA during chemotherapies and antiviral therapy. R: Rituximab; R-CHOP: Cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone plus Rituximab; R-DHAP: Cisplatin, cytarabin, dexamethasone plus Rituximab; R-IEV: Ifosfamide, etoposide, epirubicin plus Rituximab; GGT: Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase; ALT: Alanine amino-transferase; HCV: Hepatitis C viremia.

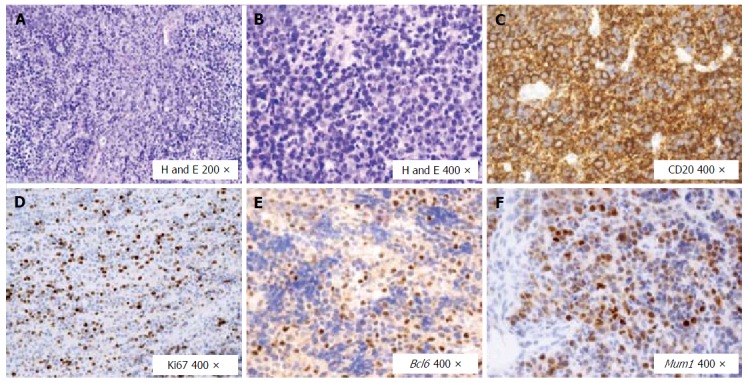

Figure 3.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of the diffuse large B cell lymphoma at the first relapse (mucosal). A: In the mucosal relapse a polymorphic lymphoid population was found; B: The rate of large lymphoid cells increased up to 80%; C: These large cells were B CD20+; D: The proliferation rate marked by Ki67 was around 50%-60% with respect to the blastic B cell population; E: The large B cells expressed the germinal center marker Bcl6 (about 50%-60%); F: Mum1 was found to be expressed now by about 70% of the cells. DLBCL: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma; H and E: Hematoxylin and eosin; CD: Clusters of differentiation; Ki67: Cellular marker for proliferation; Bcl6: B Cell lymphoma 6; Mum1: Multiple myeloma oncogene 1.

From February 2015 to March 2015 she underwent local radiotherapy on the right maxillary sinus (30 Gray). After the liver tests returned to normal levels, she started the triple DAAs regimen in the EAP, for a duration of 12 wk (Figure 2). The HCV-RNA showed a fast drop since after two weeks of AVT (42 UI/mL), while viremia became undetectable (limit of quantification according to our virological test was 15 UI/mL) after 8 wk of therapy, and persisted undetectable both at the end of AVT and 24 wk after. However, in May 2015, i.e., after 4 wk from the end of AVT, the patient experienced a new relapse of lymphoma (Figure 4). Due to the appearance of multiple cutaneous nodules on the middle third of the left arm, on the posterior region of the chest wall and on the right and left flanks, a biopsy of one of them was indicated, showing a dense lymphoid infiltrate with atypical growth pattern and cells of large size (CD20+, CD79a+, CD5+, Bcl2+, CD3-, CD30-, Bcl6-, Mum1-, Ki67 80%). A new PET scan showed multiple pathological uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose in inguinal regions and at the level of the subcutaneous nodules, while the bone marrow biopsy did not show any infiltration. Consistent with the history of two previous relapses and to the high expression of Bcl2, a histological reassessment was required on both the lymphoid tissue available at diagnosis and that from the biopsy of the subcutaneous nodule. An analysis with fluorescence in situ hybridization for the detection of lymphoma-associated chromosomal abnormalities was performed (Vysis LSI Bcl2 break apart probe, Vysis LSI Myc break apart probe), showing additive copies of Bcl2 (18q21) in 82% and rearrangement of Myc in 89% of the nuclei analyzed (8q24), respectively. Therefore, the final diagnosis was that of DHL, a more aggressive subtype of DBCL. In July 2015, the patient was firstly prescribed a cycle of ifosfamide, etoposide, epirubicin plus R (R-IEV regimen), followed by stem cell collection for a possible autologous stem cell transplantation; subsequently, she underwent a second cycle of R/IEV/R (regimen with an additive administration of R), which was burdened by infective complications requiring hospitalization and prolonged antibiotic therapies. At the last hepatological follow-up visit in November 2015, i.e., 24 wk after the end of AVT, HCV-RNA was permanently undetectable despite the immunosuppressive therapy. Afterwards, the patient was evaluated for an allogenic stem cells transplantation, which was made in another Hospital in January 2016, and she is free from lymphoma recurrence according to recent clinical and radiological evaluations.

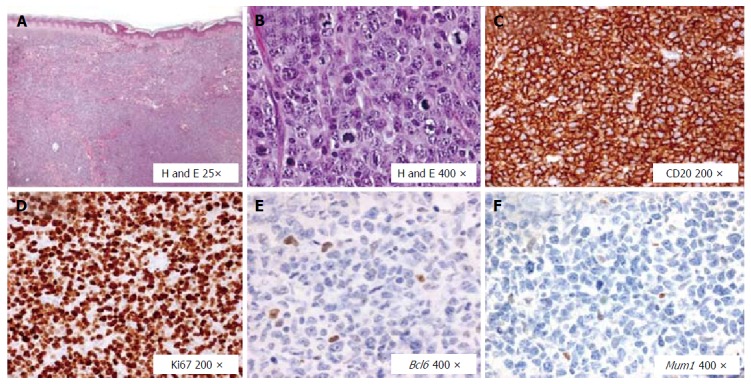

Figure 4.

Histological and immunohistochemical features of the diffuse large B cell lymphoma in the second relapse (cutaneous). A: In the cutaneous relapse a rather monomorphic lymphoid population was found; B: The rate of large lymphoid cells increased up to 100%; C: These large cells were B CD20+; D: The proliferation rate marked by Ki67 was around 95% in the blastic B cell population; E: The large B cells expressed poorly the germinal center marker Bcl6; F: Mum1 was found to be poorly expressed by the large B cells. DLBCL: Diffuse large B cell lymphoma; H and E: Hematoxylin and eosin; CD: Clusters of differentiation; Ki67: Cellular marker for proliferation; Bcl6: B Cell lymphoma 6; Mum1: Multiple myeloma oncogene 1.

DISCUSSION

The role of HCV in pathogenesis of NHL is well established. The regression of HCV-associated indolent lymphomas after a successful AVT adds the demonstration that there is a relationship between HCV and lymphomagenesis, but there are no data about the response of DHL to AVTs. Because HCV is not integrated into the host genome, there should be indirect mechanisms to induce malignancy (“hit and run theory”). The main hypothesis links the antigenic stimulation caused by CHC to the chronic proliferation of B cells, to produce firstly a polyclonal and after a monoclonal expansion of these cells resulting, in conjunction with further occurrence of additional genetic mutations, in an overt NHL[5]. Notably, several years have to pass in order to accumulate mutational changes, whereas a genetic predisposition or additional mutagenic effects in genes Bcl2, Bcl6 or Ccnd1 could explain the DHL mutation occurrence. Indeed, HCV could induce a mutator phenotype, which involves enhanced mutations of many somatic genes. In the management of HCV-related DLBCL, anthracycline-based chemotherapy, usually CHOP, associated with R (chimeric anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) is the standard of care[6]. Unlike indolent B-cell lymphomas[7], AVT does not play a significant role in HCV-positive DLBCL. Sequential immune-chemotherapy followed by ATV has been used in two studies with promising results leading to improved clinical outcome and prolonged disease free survival[8,9]. On the other hand, a French study reported a higher overall survival and progression free survival in patients treated firstly by AVT, followed in some cases by chemotherapy[10]. All these studies are developed in the “IFN era”, both alone or in combination with RBV and, more recently, with protease inhibitors like telaprevir and boceprevir. An IFN-based immunomodulatory and anti-angiogenetic mechanism could be supposed, although IFN-based AVTs cannot be started in most cases, because of contraindications and heavy side effects.

A few reports demonstrated lymphoma regression after HCV clearance with new DAAs. Rossotti et al[11] reported a rapid virological and hematological response with the combination of a NS3/NS4A inhibitor (faldaprevir) and a non-nucleoside NS5B inhibitor (deleobuvir) in a patient with HCV associated splenic marginal zone lymphoma. In another report, Sultanik et al[12] showed complete regression of MZL after 12 wk of therapy with sofosbuvir (an NS5B RNA-dependent RNA polymerase inhibitor) and RBV. In a case series from France of five patients with HCV-related lymphoma, two DLBCL were successfully treated with sofosbuvir and daclatasvir (an NS5A protease inhibitor), with complete hematological response after 6 mo[13]. There are no reported cases of DHL and CHC treated by new DAAs.

According to clinical data, we could exclude an advanced liver fibrosis in our patient and we estimated a minimal risk of liver decompensation. Therefore, the patient was firstly successfully treated with R-CHOP, but after the first hematological relapse, a new immunosuppressive therapy with R-DHAP schedule caused an overt liver failure. R has been described to enhance viral replication due to the immune system imbalance, but the rate of severe hepatic complications remains low, with some exceptions, such as in presence of hepatitis B virus or HIV infection, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma[7,14]. There are controversial studies about the impairment of liver function, which could be caused both by a toxicity of immune-chemotherapy treatment and by HCV reactivation. Indeed, it is not clear if the anecdotal episodes of liver failure in this setting are due to higher HCV replication and enhanced necro-inflammatory activity, or to a direct chemo-toxicity. Chemotherapy-induced HCV reactivation in DLBCL is rarely reported, whereas there are no data about HCV and DHL[15-17]. In our case the liver failure may have been caused by an add-on effect of HCV reactivation and liver chemo-toxicity, as well suggested by a higher increase of Gamma-Glutamyl Transpeptidase, marker of liver toxicity, instead of a pure elevation of Alanine Aminotransferase, a possible expression of an inflammatory response HCV-mediated. Interestingly, during the liver failure HCV-RNA slightly dropped, so we can suppose that the event was caused by immune re-activation rather than by HCV direct effect on the necro-inflammatory activity. Following the second immune-chemotherapy and after recovering from the acute liver failure, the patient started antiviral therapy with second generation DAAs: OBV/PTV/r and DSV. This multi-targeted 3-DAAs regimen in combination with or without RBV is approved in many countries to treat HCV genotype 1-4 infection. Approval for the treatment of HCV genotype 1 patients with compensated cirrhosis was based on the evidence of a phase 3 trial of 380 patients in which OBV/PTV/r and DSV plus RBV achieved SVR rates at post-treatment week 12 (SVR12) of 91.8% and 95.9% after 12 or 24 wk of therapy, respectively[18]. In the past, the AVTs for HCV were conceived with IFN-based regimens, so an immunomodulatory effect due to interactions with both the adaptive and innate immune response of the host, further than an anti-inflammatory and antiviral effect by inhibiting the synthesis of various cytokines, were possibly responsible for the remission of HCV-related lymphomas. In this context, at the moment, there are no definitive data about IFN free therapies, and it remains to be solved whether IFN is crucial for its direct antitumor and anti-proliferative effect against NHL further than for its antiviral effect.

In conclusion, this is the first case, to our knowledge, of DHL and CHC successfully treated by new DAAs. According to our experience, DHL must be suspected in case of HCV-related lymphoma, and an early diagnosis could direct towards a different hematological management, because a poor prognosis should be expected. Moreover, DAAs triple regimen with OBV/PTV/r and DSV achieves a rapid virological response, and the result is sustained during immunosuppressive therapy, without evidence of HCV reactivation. Finally, we can suggest that in cases of aggressive HCV-related lymphoma, it is mandatory to treat the HCV infection with the new IFN-free regimens at least after the first chemotherapy cycle. This choice could avoid a liver failure in case of re-treatment with hepatotoxic drugs, and it allows a better and safer management of hematological disease. A potential favorable effect of the AVTs on DHL regression should be investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cristina Madaudo and Lucia Lo Scalzo for preparing figures and graphics.

COMMENTS

Case characteristics

A 39-year-old Caucasian woman presented with neck lymph nodes enlargement and hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infection.

Clinical diagnosis

Painless swelling in the right side of the neck with increased thickness.

Differential diagnosis

Inflammatory process of the throat, metastatic cancer of head-neck sites, lymphoproliferative disease.

Laboratory diagnosis

All blood tests were within normal limits except for high HCV-viremia.

Imaging diagnosis

Computed tomography showed multiple lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm.

Pathological diagnosis

Double-hit B cell lymphoma.

Treatments

Chemotherapy, radiotherapy and antiviral therapy for HCV.

Related reports

Double-hit B cell lymphoma is a rare entity with no standardized chemotherapeutic strategies and its association with HCV-infection is not ever been investigated. There are no reports about the efficacy of antiviral therapy for HCV plus chemotherapies, in order to cure this pathology in presence of HCV.

Terms explanation

HCV could induce B cell proliferation and cause non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The typical HCV-related lymphomas are marginal zone lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma. Double-hit B cell (DHL) is a new kind of lymphoma with more aggressive outcome, and it is characterized by chromosomal rearrangements, specifically of Myc oncogene and either B cell lymphoma 2 and B cell lymphoma 6 oncogenes or gene for Cyclin D1.

Experiences and lessons

DHL must be suspected in case of HCV-related lymphoma, and an early diagnosis could direct towards a different hematological management, because a poor prognosis should be expected. A potential favorable effect of new antiviral therapies on DHL regression should be investigated.

Peer-review

This manuscript has reported the first case of DHL and CHC successfully treated by new DAA.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Institutional review board statement: This case report was exempt from the Institutional Review Board standards at University of Campus Bio Medico of Rome.

Informed consent statement: The patient involved in this clinical case gave her written informed consent authorizing use and disclosure of her protected health information.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

Peer-review started: March 24, 2016

First decision: June 12, 2016

Article in press: August 16, 2016

P- Reviewer: Einberg AP, El-Shabrawi MH, Ji FP S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Negri E, Little D, Boiocchi M, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S. B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:1–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellicelli AM, Marignani M, Zoli V, Romano M, Morrone A, Nosotti L, Barbaro G, Picardi A, Gentilucci UV, Remotti D, et al. Hepatitis C virus-related B cell subtypes in non Hodgkin’s lymphoma. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:278–284. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v3.i11.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida M, Ichikawa A, Miyoshi H, Kiyasu J, Kimura Y, Arakawa F, Niino D, Ohshima K. Clinicopathological features of double-hit B-cell lymphomas with MYC and BCL2, BCL6 or CCND1 rearrangements. Pathol Int. 2015;65:519–527. doi: 10.1111/pin.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aukema SM, Siebert R, Schuuring E, van Imhoff GW, Kluin-Nelemans HC, Boerma EJ, Kluin PM. Double-hit B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2011;117:2319–2331. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-297879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weng WK, Levy S. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and lymphomagenesis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44:1113–1120. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000076972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coiffier B. Standard treatment of advanced-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 2006;43:213–220. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcaini L, Merli M, Passamonti F, Bruno R, Brusamolino E, Sacchi P, Rattotti S, Orlandi E, Rumi E, Ferretti V, et al. Impact of treatment-related liver toxicity on the outcome of HCV-positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Am J Hematol. 2010;85:46–50. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.La Mura V, De Renzo A, Perna F, D’Agostino D, Masarone M, Romano M, Bruno S, Torella R, Persico M. Antiviral therapy after complete response to chemotherapy could be efficacious in HCV-positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Hepatol. 2008;49:557–563. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Musto P, Dell’Olio M, La Sala A, Mantuano S, Cascavilla N. Diffuse B-large cell lymphomas (DBLCL) with hepatitis-C virus (HCV) infection: clinical outcome and preliminary results of a pilot study combining R-CHOP with antiviral therapy. Blood. 2005;106:688a. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michot JM, Canioni D, Driss H, Alric L, Cacoub P, Suarez F, Sibon D, Thieblemont C, Dupuis J, Terrier B, et al. Antiviral therapy is associated with a better survival in patients with hepatitis C virus and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, ANRS HC-13 lympho-C study. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:197–203. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rossotti R, Travi G, Pazzi A, Baiguera C, Morra E, Puoti M. Rapid clearance of HCV-related splenic marginal zone lymphoma under an interferon-free, NS3/NS4A inhibitor-based treatment. A case report. J Hepatol. 2015;62:234–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sultanik P, Klotz C, Brault P, Pol S, Mallet V. Regression of an HCV-associated disseminated marginal zone lymphoma under IFN-free antiviral treatment. Blood. 2015;125:2446–2447. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-618652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrier P, Jaccard A, Jacques J, Tabouret T, Debette-Gratien M, Abraham J, Mesturoux L, Marquet P, Alain S, Sautereau D, et al. HCV-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas and new direct antiviral agents. Liver Int. 2015;35:2222–2227. doi: 10.1111/liv.12897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Visco C, Finotto S. Hepatitis C virus and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: Pathogenesis, behavior and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11054–11061. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh CY, Huang HH, Lin CY, Chung LW, Liao YM, Bai LY, Chiu CF. Rituximab-induced hepatitis C virus reactivation after spontaneous remission in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2584–2586. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ennishi D, Maeda Y, Niitsu N, Kojima M, Izutsu K, Takizawa J, Kusumoto S, Okamoto M, Yokoyama M, Takamatsu Y, et al. Hepatic toxicity and prognosis in hepatitis C virus-infected patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-containing chemotherapy regimens: a Japanese multicenter analysis. Blood. 2010;116:5119–5125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-289231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foran JM. Hepatitis C in the rituximab era. Blood. 2010;116:5081–5082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-307827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feld JJ, Moreno C, Trinh R, Tam E, Bourgeois S, Horsmans Y, Elkhashab M, Bernstein DE, Younes Z, Reindollar RW, et al. Sustained virologic response of 100% in HCV genotype 1b patients with cirrhosis receiving ombitasvir/paritaprevir/r and dasabuvir for 12weeks. J Hepatol. 2016;64:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]