Abstract

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is known for nosocomial habitat. Infective endocarditis due to this organism is rare and challenging because of resistance to multiple broad-spectrum antibiotic regimens. Early detection and appropriate antibiotic based on culture sensitivity reports are the key to its management. We report the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of two cases of infective endocarditis caused by S. maltophilia.

Keywords: S. maltophilia, Infective endocarditis, Nosocomial, In-hospital habitat

1. Background

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia (S. maltophilia) is a nonfermentative, gram-negative, aerobic bacillus that is widely distributed in the nature. In a hospital setting, it has been found in water-related sources and contaminated medical equipments.1, 2, 3 Although S. maltophilia is not highly virulent, its treatment is challenging because of its resistance to multiple antibiotics. Therefore, the relentless progression of patient's underlying illness adds to higher causalities.4, 5, 6, 7 Infective endocarditis due to S. maltophilia is very rare. Only 41 cases have been reported so far worldwide, most of which required surgical treatment. In this report, we share our experience of two cases of infective endocarditis managed by culture-sensitive antibiotics.

2. Case report

2.1. Case 1

A 35-year-old man was admitted to our hospital 3 months back with history of fever with chills for five days. The patient had undergone PBMV for severe rheumatic mitral stenosis 2 weeks prior to this episode. No other predisposition was found. There was no history of dental procedures or injections of intravenous drugs. On physical examination, blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, pulse rate 85/min, and body temperature of 38 °C. Cardiac examination revealed loud S1 and P2 with grade III mid-diastolic murmur at the apex. The remaining physical examination was unremarkable. There were no peripheral signs of infective endocarditis. Laboratory tests showed that his Hemoglobin was 12.8 gm/dl, white blood cell (WBC) was 18,900/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 52 mm in first hour, and urinalysis was normal. Renal parameters were normal. Cardiomegaly was apparent in chest radiography.12 Electrocardiogram revealed a normal sinus rhythm. The transthoracic echo demonstrated moderate mitral stenosis, severe eccentric mitral regurgitation, which was not there previously, and suspicious vegetation was present on mitral valve. The transesophagial echocardiogram revealed freely mobile sessile vegetation of size 5 mm × 5 mm over both anterior and posterior mitral leaflets (Fig. 1). The patient was started with a regimen of ceftriaxone and gentamycin. S. maltophilia was identified on blood culture and the antibiotics were changed to co-trimoxazole and levofloxacin as per culture sensitivity report. After 1 week of antibiotics, patient became afebrile, and repeat transesophagial echo after 2 weeks revealed disappearance of vegetation (Fig. 2). Antibiotics were continued for 6 weeks. He was discharged successfully.

Fig. 1.

Transesophagial echocardiography (TEE) image is showing two mobile vegetations over anterior and posterior mitral leaflet before treatment of case number one.

Fig. 2.

Transesophagial echocardiography (TEE) image is showing disappearance of vegetation after 2 weeks of culture sensitive-based antibiotic regimen of case one.

2.2. Case 2

A 40-year-old man was admitted for fever and chill for a period of 2 months following mechanical valve replacement (27 mm Carbo-Medics) of mitral valve for severe rheumatic mitral stenosis. No other comorbidities were found. There was no history of dental procedures or injections of intravenous drugs. At presentation, he was drowsy, pale, and edematous with raised jugular venous pulsation. Blood pressure was 90/60 mmHg, pulse rate 120/min, and body temperature was 38 °C. Cardiac examination revealed soft S1, normal S2 with metallic heart sound. There was no audible murmur. Chest examination revealed bilateral basal crepitations. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) at presentation was E3 M5 V4 with no focal neurological deficits. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory tests showed that Hb was 7.6 gm/dl, WBC 17,500/L, and ESR was 80 mm/hr. The renal parameters were elevated with urea of 65 mg/dl and serum creatinine of 3.0 mg/dl. Arterial Blood Gas (ABG) revealed metabolic acidosis. Increased cardiothoracic ratio and features suggestive of pulmonary edema were observed on chest radiography. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus tachycardia. The transthoracic echo demonstrated large mobile vegetation of 2 cm × 1.6 cm in size on prosthetic mitral valve (Fig. 3). There was mild paravalvular leak with partial dehiscence, moderate mitral regurgitation, moderate tricuspid valve regurgitation, moderate pulmonary arterial hypertension, and moderate left ventricular dysfunction. The patient was empirically started on vancomycin and ceftriaxone. Initially, blood cultures grew MRSA sensitive to only teicoplanin, gentamycin, and linezolid. Fever continued with spikes. Supportive treatment was given in the form of inotropic support, vasodilators, and peritoneal dialysis for rapidly worsening renal dysfunction. By the time, the repeat blood culture could identify the culprit bacteria to be S. maltophilia, the patient died of septicemia and renal dysfunction.

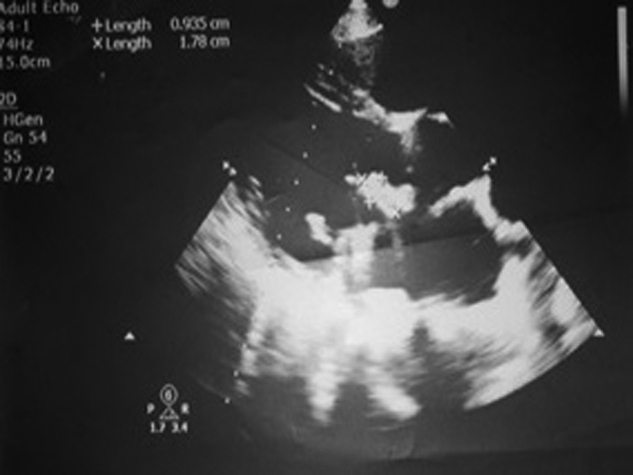

Fig. 3.

Transesophagial echocardiography (TEE) image is showing mobile vegetation over prosthetic mitral leaflet of case 2 who died in hospital.

3. Discussion

We share the challenges in managing two cases of S. maltophilia endocarditis of different outcomes. One patient was managed successfully with culture-guided early antibiotic therapy, while other case succumbed before the arrival of culture report.

S. maltophilia endocarditis is a rare disease. Only 41 cases have been reported around the world before our observations (Table 1). The clinical features vary from case to case. In-hospital habitat is the reservoir. S. maltophilia endocarditis is likely to develop under specific conditions, such as the use of central venous lines, prior cardiac surgery, and intravenous drug abuse.4, 5, 6, 7 Thus, S. maltophilia from contaminated medical equipment in hospitals may cause endocarditis when the skin barrier is broken.2, 6 In particular, prior valve replacement is one of the predisposing factors that accounts for approximately 40–60% of the endocarditis cases.5, 6, 7

Table 1.

The brief summary of worldwide experience of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infectious endocarditis.

| Case | Ref. | Clinical profile |

Management |

Complications | Outcomes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age/Sex | Predisposing factors | Valve involved | MM | Surgery | ||||

| 1 | [9] | 26/M | Recent valve replacement (<1 month) | PMV, ASD patch | CHL, KAN, COL | Yes | Multiple septic emboli | D |

| 2 | [9] | 30/M | Recent valve replacement (<1 month) | PMV, ASD patch | CHL | No | None | C |

| 3 | [9] | 65/F | Cystoscopy, valve replacement (7 months) | PMV | CAR, GEN, KAN, CHL, PEN, POL | Yes | Persistent bacteremia | C |

| 4 | [9] | 35/M | Recent valve replacement (early), rheumatic carditis | PMV | CAR, GEN, SXT | No | None | C |

| 5 | [9] | 38/M | None | PMV | STR, PEN | No | Septic emboli, MI | D |

| 6 | [9] | 22/M | IVDU | PAV | CAR, AMK, SXT | Yes | CHF, septic emboli | C |

| 7 | [9] | 31/F | IVDU, dental treatment | PAV | CAR, KAN, SXT | Yes | Perivalvular abscess | C |

| 8 | [9] | 57/M | IVDU, rheumatic carditis | NAV, NMV | POL, SXT | No | Septic emboli | C |

| 9 | [9] | 25/M | None | VSD repair | GEN, CHL | No | NR | D |

| 10 | [9] | 33/M | IVDU, aortic stenosis, atrial fistula | NAV, NTV | TIC, MOX, SXT | Yes | CHF, myocardial abscess | D |

| 11 | [9] | NR | CVC | NTV | NR | NR | NR | D |

| 12 | [9] | NR | NR | NAV | NR | NR | NR | D |

| 13 | [9] | NR | CVC | NAV | NR | NR | NR | C |

| 14 | [9] | 33/M | IVDU, dental treatment | PAV | SXT, AMC, GEN | Yes | Perivalvular abscess | C |

| 15 | [9] | 56/M | Recent valve replacement (early) | PAV | CAZ, GEN, SXT | Yes | Septic emboli | D |

| 16 | [9] | 32/M | IVDU, subcutaneous reservoir | NTV | SXT | No | CHF | D |

| 17 | [9] | 28/M | IVDU | NAV | CIP, GEN | Yes | Myocardial abscess | C |

| 18 | [9] | 60/F | Ventriculo-atrial shunt | NTV | TIM, SXT | No | Lung abscess | C |

| 19 | [9] | 36/M | Dental treatment (3 months) | NAV | TZP, GEN | Yes | CHF | C |

| 20 | [9] | 69/F | Recent valve replacement (3 months) | PMV, PAV | CAZ, GEN, CIP, SXT | Yes | CHF, persistent bacteremia | D |

| 21 | [10] | 37/M | Recent mitral valvuloplasty (early) | PMV | CAZ, AMK, CIP then TIM, SXT, COL | Yes | None | C |

| 22 | [9] | 58/F | Recent valve replacement (3 months) | PMV | SXT | Yes | None | C |

| 23 | [9] | 62/M | Recent valve replacement (6 months) | PAV | CIP, CHL | No | Aortic dissection | C |

| 24 | [9] | 40/M | Recent valve replacement (9 months) | PAV | TIM, SXT | No | None | C |

| 25 | [9] | 44/M | Rheumatic valvular disease | PMV | VAN, GEN | No | Recurrence with septic emboli treated by TMP-SMZ + TOB and surgery | C |

| 26 | [11] | 44/M | IVDU, HIV, dental treatment, rheumatic aortic and mitral disease | NMV, NAV | LVX, SXT | No | None | C |

| 27 | [9] | 56/F | CVC | NAV | FEP, CIP, SXT | No | None | C |

| 28 | [12] | 65/F | NR | PAV | NR | NR | CHF, paravalvular abscess | NA |

| 29 | [7] | 34/F | Peripheral catheter | PMV | SXT, GEN | No | None | C |

| 30 | [13] | 38/M | Recent valve replacement (1 year) | PAV | SXT, TIM | Yes | Subannular abscess | C |

| 31 | [14] | 28/M | Recent valve replacement (3 weeks) | PAV | SXT, CAZ | Yes | None | C |

| 32 | [15] | – | Pacemaker | Pacemaker pocket | – | Yes | None | C |

| 33–39 | [8] | 68–84 | Recent valve replacement | PAV | CAZ | Yes | CNS complications in 4 | 3D |

| 40 | [16] | 78/F | None | PMV | SXT, CIP, TZP | Yes | Multiple cerebral infarction and paravalvular abscess | D |

| 41 | [17] | 23/F | Autoimmunity related to SLE | |||||

| 42 | Case 1 | 35/M | Rheumatic heart disease | Native mitral valve | SXT, LVX | No | None | C |

| 43 | Case 2 | 40/M | Recent valve replacement (4 months) | PMV | VAN, GEN | No | Renal failure | D |

Out of 43 cases, 14 patients (33%) died out of various complications.

Abbreviations: AMC, ampicillin; AMK, amikacin; ASD, atrial septal defect; CAR, carbenicillin; CAZ, ceftazidime; CHF, congestive heart failure; CHL, chloramphenicol; CIP, ciprofloxacin; COL, colistin; CVC, central venous catheter; FEP, cefepime; GEN, gentamicin; IVDU, intravenous drug user; KAN, kanamycin; LVX, levofloxacin; MI, myocardial infarction; MOX, moxalactam; NAV, natural aortic valve; NMV, natural mitral valve; NR, not reported; PAV, prosthetic aortic valve; PEN, penicillin; PMV, prosthetic mitral valve; POL, polymyxin; PR, present report; STR, streptomycin; SXT, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; TIC, ticarcillin; TIM, ticarcillin-clavulanic acid; TOB, tobramycin; TZP, piperacillin-tazobactam; VAN, vancomycin; VSD, ventricular septal defect. D, died; C, cure; MM, medical management; SLE, systemic lupus erythematous.

Treatment of endocarditis caused by S. maltophilia comprises appropriate antibiotic therapy and removal of indwelling infected foreign material in the body. Because of limited experience and resistance to multiple antibiotics, the treatment is purely based on consensus and regional culture sensitivity pattern. S. maltophilia is resistant to penicillin, cephalosporin, and Carbapenems. Sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is selected as the first-line antibiotic, supported by in vitro susceptibility.2, 3 Since sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim is bacteriostatic against the most isolates, it is used in combination with other antibiotics for synergistic effect. The difficulty in treating S. maltophilia endocarditis with antibiotic therapy arises due to sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim intolerance. Several reports have stated that combination therapy with fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, and 3rd or 4th generation cephalosporin is effective.6, 8 Discrepancies between the in vitro susceptibility data and clinical outcome have been noted in the case of S. maltophilia infections.1, 3 Both morbidity and mortality rates are high in cases of endocarditis caused by S. maltophilia. The overall incidence of mortality is approximately 34.8% (15/43), as has been summarized from case reports around the world (Table 1). Complications such as cerebral vascular disease, congestive heart failure, and organic abscess are seen in 70–80% of patients5, 6, 7 because of antibiotic resistance. Autoimmunity could be included as a novel predisposing factor for S. maltophilia endocarditis, as reported in case report by Carrillo-Córdova et al.17 Until now, to the best of our knowledge, there is no published report of infective endocarditis caused by S. maltophilia from Indian subcontinent.

4. Conclusion

The true epidemiological profile of infective endocarditis due to S. maltophilia is emerging. The treatment for this organism has not been addressed in most recently updated infective endocarditis guidelines. The very reason may be its rare occurrence and paucity of experience. It is important to identify this microorganism as quickly as possible, since S. maltophilia is resistant to first line antibiotic therapy generally used in case of nosocomial infections. This case report reemphasizes the meticulous steps in the prevention of device-related infections in operation theaters and cardiac catheterization laboratories. These are the first two case reports of infective endocarditis caused by S. maltophilia from India.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Denton M., Kerr K.G. Microbiological and clinical aspects of infection associated with Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:57–80. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dignani M.C., Grazziutti M., Anaissie E. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia infections. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;24:89–98. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Looney W.J., Narita M., Muhlemann K. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: an emerging opportunist human pathogen. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:312–323. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munter R.G., Yinnon A.M., Schlesinger Y., Hershko C. Infective endocarditis due to Stenotrophomonas (Xanthomonas) maltophilia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17:353–356. doi: 10.1007/BF01709460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan I.A., Mehta N.J. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis: a systematic review. Angiology. 2002;53:49–55. doi: 10.1177/000331970205300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crum N.F., Utz G.C., Wallace M.R. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:925–927. doi: 10.1080/0036554021000026977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bayle S., Rovery C., Sbragia D., Brouqui P. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia prosthetic valve endocarditis: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:174. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muller-Premru M., Gabrijelcic T., Gersak B. Cluster of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis after prosthetic valve replacement. Wein Klin Wochenschr. 2008;120:566–570. doi: 10.1007/s00508-008-0994-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez R.R., Lado Lado F.L., Sanchez A. Endocarditis caused by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: report of a case and review of literature. Ann Med Interna. 2003;20:312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu P.S., Lu C.Y., Chang L.Y. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia bacteremia in pediatric patients—a 10-year analysis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2006;39:144–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Senol E. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: the significance and role as a nosocomial pathogen. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mermel L.A., Farr B.M., Sherertz R.J. Guidelines for the management of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:1249–1272. doi: 10.1086/320001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ucak A., Goksel O.S., Inan K. Prosthetic aortic valve endocarditis due to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia complicated by sub-annular abscess. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108:258–260. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2008.11680216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanioğlu S., Sokullu O., Yavuz S.S., Kut M.S., Palaz F.K., Bilgen F.S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis treated with moxifloxacin-ceftazidime combination and annular wrapping technique. Anadolu Kardiyol Derg. 2008;8:70–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takigawa M., Noda T., Kurita T. Extremely late pacemaker-infective endocarditis due to Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. Cardiology. 2008;110:226–229. doi: 10.1159/000112404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katayama T., Tsuruya Y., Ishikawa S. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis of prosthetic mitral valve. Intern Med. 2010;49:1775–1777. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.3701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carrillo-Córdova J.R., Amezcua-Guerra L.M. Autoimmunity as a possible predisposing factor for Stenotrophomonas maltophilia endocarditis. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2012;82:204–207. doi: 10.1016/j.acmx.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]