Abstract

The rapid escalation in prices of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) for multiple sclerosis (MS) over the past decade has resulted in a dramatic overall increase in the costs of MS-related care. In this article, we outline various approaches whereby neurologists can contribute to responsible cost containment while maintaining, and even enhancing, the quality of MS care. The premise of the article is that clinicians are uniquely positioned to introduce innovative management strategies that are both medically sound and cost-efficient. We describe our “top 5” recommendations, including strategies for customizing relapse treatment; developing alternative dosing schedules for Food and Drug Administration–approved MS DMTs; using off-label therapies for relapse suppression; and limiting the use of DMTs to those who clearly fulfill diagnostic criteria, and who might benefit from continued use over time. These suggestions are well-grounded in the literature and our personal experience, but are not always supported with rigorous Class I evidence as yet. We advocate for neurologists to take a greater role in shaping clinical research agendas and helping to establish cost-effective approaches on a firm empiric basis.

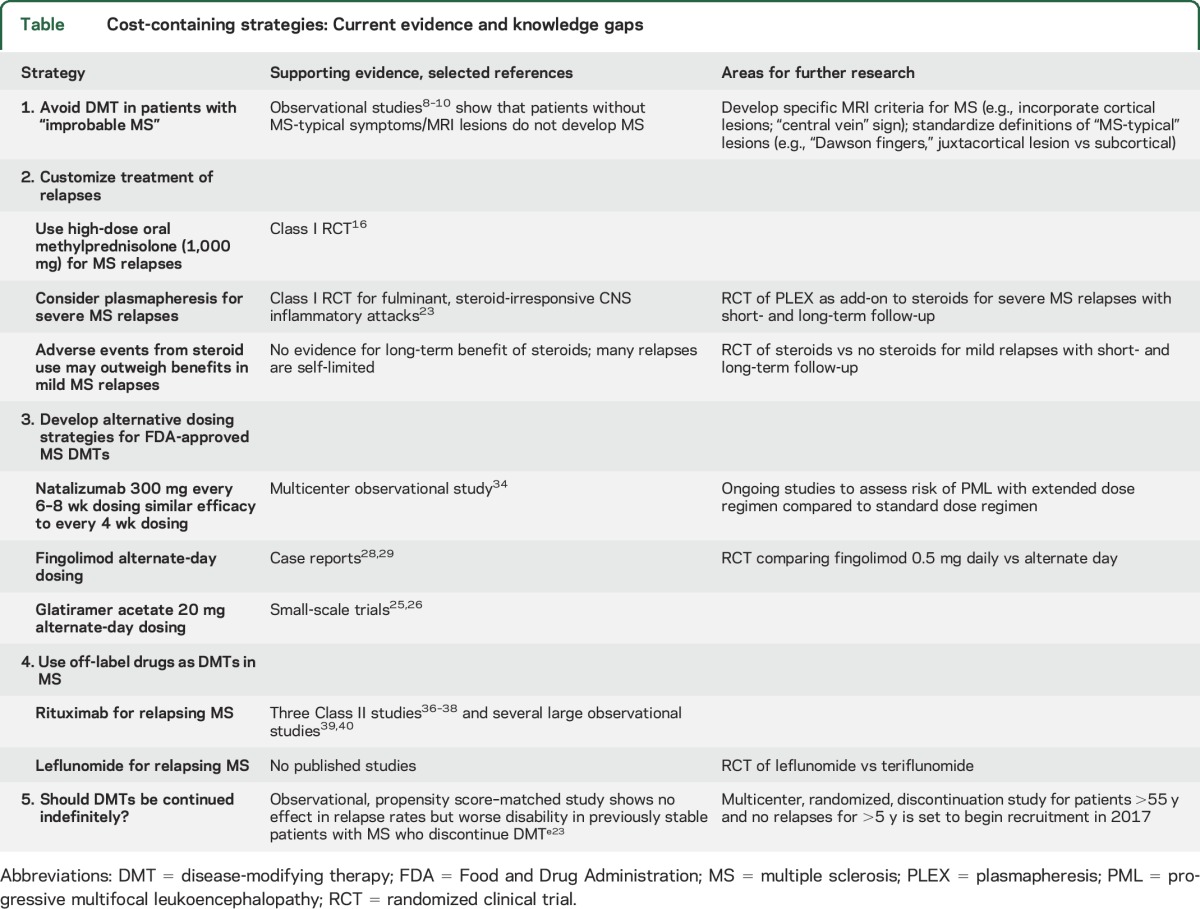

There have been considerable advances in the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS) over the past 2 decades, and recent evidence suggests that specialized care for patients with MS is associated with “decreased adverse events and [decreased] usage of acute and post-acute health care resources.”1 At the same time, costs of MS care are rising, largely because of the rapid escalation in prices of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs).2 Insurance carriers and specialty pharmacies have responded by seeking to deny or limit payments for costly therapies, using “step edits” (a requirement to fail one or more therapies before approving and paying for an alternative approved therapy), “tiered formularies” (different copays for DMTs to treat the same disease), and escalating copays, deductibles, and coinsurance, so as to transfer more costs to the insured patient. All of these practices interfere with shared decision-making between patents and their doctors and may have detrimental effects on quality of MS care.e1 In an effort to curtail medical costs, the “Choosing Wisely” campaign3 supported by the American Academy of Neurology put forth a list of 5 neurologic practices that could, or should, be eliminated, including use of first-line DMTs in nonrelapsing, secondary progressive MS. Many in the MS community thought that this broad recommendation failed to consider the nuances of which patients with MS might benefit from continued use of DMTs.4 An alternative, more prescriptive approach to cost containment is to introduce new strategies for managing MS that are medically and economically sound. We outline here 5 possible strategies, but many others could be proposed as well. Our suggestions, summarized in the table, should not be viewed as practice guidelines—they are not always based on rigorous Class I evidence as yet—but as an effort to set a patient-centered, neurologist-driven agenda for clinical research in MS that could help improve outcomes and decrease costs.

Table.

Cost-containing strategies: Current evidence and knowledge gaps

1. Avoid DMT in patients with “improbable MS.”

Misdiagnosis of MS is neither a new nor an uncommon phenomenon. It is estimated that 5% to 13% of all “MS patients” do not have MS.5 What is new is the economic cost of misdiagnosis associated with use of expensive MS DMTs. The scope of the problem was highlighted by a survey published in 2012, in which 112 MS specialists were asked to estimate how many patients were referred to them with diagnosis of MS who “almost certainly did not have MS.” The survey responders estimated seeing 598 such patients over a 1-year period, of whom an estimated 279 patients (47%) were receiving a DMT for MS.6

There are many roads to MS misdiagnosis, but one particularly common scenario involves a (poly)symptomatic, but neurologically intact patient with subcortical “unidentified bright objects” (UBOs) on T2-weighted MRI sequences. Subcortical UBOs are nonspecific and are not included as part of the formal diagnostic criteria in MS.e2 Isolated subcortical UBOs are highly uncharacteristic of MS, yet their presence often triggers mention of “demyelinating disease” in MRI reports.7 Reassuringly, patients without clinical history, neurologic deficits, or MRI lesions characteristic of MS rarely, if ever, progress to MS.8–10 Therefore, such patients should not be prescribed MS DMTs, which, in addition to high costs, are associated with potentially severe side effects. Indeed, one of the first natalizumab-related fatal cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) was described in a patient with no MS lesions in the optic nerve, brain, or spinal cord at autopsy.11 Thus, while we agree with the concept of early and aggressive treatment of MS, this approach requires a high degree of diagnostic certainty at the onset of treatment.

An important contributing factor to the high misdiagnosis rates is lack of specific serum or CSF biomarkers of MS, or even of radiographic criteria for differentiating demyelinating lesions from lesions of other causes. The existing criteria for MS (Barkhof, Swanton) are designed not for diagnosing MS, but for identifying patients with clinically isolated syndrome—first MS-like neurologic event—who are at high risk of developing MS.5,e3 We urgently need practical radiographic criteria or other biomarkers for ruling out MS in a patient with low pretest probability of this disease and MS-atypical lesions, and ruling in patients with clinically or radiologically isolated syndromes that often precede clinical MS. One promising strategy is to optimize MRI sequences for detection of features suggestive of demyelination, such as central veins within lesions. Central veins are found in more than 40% of demyelinating lesions, but rarely in microvascular disease12 or migraine,e4 and are thus particularly useful in distinguishing between MS and the nonspecific subcortical lesions seen in the other conditions. Other MRI abnormalities of potential utility for MS diagnosis are cortical lesions, which are seen in 40% of radiologically isolated syndromes,13 but not in migraine,14 and iron deposition within lesions.e5

2. Customize treatment of relapses.

Corticosteroids are the mainstay for treatment of acute attacks of MS, usually delivered as methylprednisolone 1,000 mg per day IV for 3 to 5 days, sometimes followed with an oral taper. Inadequate oral dosing of corticosteroids for acute optic neuritis (prednisone 1 mg/kg for 14 days) appears to be ineffective, and even detrimental,15 but when oral steroids are given in doses that are (near) equivalent to IV, there appears to be no significant difference in outcomes of relapses. A recent randomized trial showed that high-dose methylprednisolone 1,000 mg given orally for 3 days was noninferior to the same dose given IV.16 The clinical equivalence is biologically plausible as 82% of oral methylprednisolone is bioavailable.17 Oral delivery eliminates the relatively high cost of IV infusions ($799.35 for 1 hour of nonchemo outpatient infusion at the University of Colorado Hospital) and is patient-friendly. One logistic difficulty is the lack of prepackaged oral high-dose steroid preparations. To circumvent this problem, one could use compounding pharmacies (up to 500 mg of methylprednisolone could be compounded in a single capsule at a cost of $264 for a 5-day, 10-capsule course; Pine Pharmacy, Buffalo, NY), or mix 1,000 mg of lyophilized methylprednisolone intended for IV infusion ($56.75 per dose at the University of Colorado Hospital) with juices or other flavored drinks to make the concoction more palatable. However, there is no evidence that Acthar gel (adrenocorticotropic hormone) is in any way superior to methylprednisolone for MS relapses—indirect comparisons suggest that it may be associated with more adverse events18—and its current average wholesale price of $40,840.80 for a 5-mL/400-unit bottlee6 makes routine use of this product for MS relapses difficult to justify.

All relapses are counted as equal for purposes of calculating annualized relapse rates in clinical trials, but in practice they vary widely in severity. Some relapses are mild and self-limited, and may be difficult to differentiate from the transient worsening due to physiologic or psychologic stressors (pseudo-relapses). It is uncertain whether risk of an adverse event from steroids outweighs potential benefits of treatment in such instances. However, approximately half of relapses result in persistent deficits, and nearly a third in marked neurologic deterioration (sustained ≥1 point increase on the Expanded Disability Status Scale).19,20 Clearly, there is room for improvement in managing steroid-nonresponsive MS relapses. IV immunoglobulin has been subjected to rigorous trials with disappointing results. IV immunoglobulin did not benefit recovery from acute optic neuritis when used as a solo agent,21 and it did not appreciably improve postrelapse outcomes when used as an add-on to steroids.22 Plasmapheresis, however, has shown benefit for fulminant, steroid-unresponsive CNS inflammatory attacks in a Class I, randomized, sham-controlled trial.23 It would be worthwhile to conduct a similar trial for severe MS relapses to determine whether plasmapheresis can improve long-term outcomes in MS, thereby potentially justifying the initial investment.

3. Develop alternative dosing strategies for Food and Drug Administration–approved MS DMTs.

Efficacy of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved DMTs has been demonstrated in large randomized trials, but dose and schedule selection for these agents has not always been evidence-based. For example, glatiramer acetate is now believed to exert its action through a broad range of mostly long-term effects24 that would not necessarily require daily administration as in the pivotal trials. Indeed, 2 small-scale studies of glatiramer acetate 20 mg every other day suggest similar efficacy, but better tolerability, of alternate-day dosing compared to daily dosing,25,26 and glatiramer acetate is now marketed as 40 mg 3 times weekly based on similar outcomes as 20 mg daily.e7 Another candidate for frequency reduction is fingolimod, whose half-life for a 0.5-mg capsule taken daily is 6 to 9 days, and its presumed mechanism of action is via sequestration of lymphocytes within lymph nodes.27 There is anecdotal support for fingolimod's efficacy at lower frequency (e.g., every other day) based on our experience and case reports.28,29 The ongoing, industry-sponsored trial of 0.25-mg vs 0.5-mg daily dosing of fingolimod vs glatiramer acetate 20 mg daily30 will address the question of whether each fingolimod pill could be halved without sacrificing efficacy, but not whether the number of pills could be halved. From a cost-of-care perspective, however, a noninferiority trial of alternate-day vs daily dosing of fingolimod would be preferable. Absent such a trial, clinicians could systematically collect and publish observational data on their patients receiving fingolimod on an alternate-day schedule.

A particularly important example of a DMT for which alternate dosing may not only be cost-saving, but also life-saving is natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks lymphocyte attachment to vascular cell adhesion molecule receptors on endothelial surfaces, thereby blocking entry of activated T and B lymphocytes into the CNS. Natalizumab is approved for every 28 days dosing, yet vascular cell adhesion molecule receptor saturation of >50% is maintained for 8 weeks or more after infusion.31 This observation may help explain why disease reactivation is virtually never seen less than 8 weeks after the last natalizumab infusion.32,33 An investigator-initiated, multicenter observational study compared efficacy of natalizumab dosing interval extended up to 8 weeks and 5 days in 905 patients with standard, every 28 days natalizumab dosing in 1,093 patients.34 Both groups had excellent response to natalizumab, and the extended dose group had even fewer relapses and new T2 lesions than the standard interval dose group. Despite higher risk factors for development of PML in the extended dosing group (e.g., higher percentage on individuals exposed to the JC virus that causes PML, longer exposure to natalizumab, and higher use of prior immunosuppression), no cases of PML have been observed in the extended dose group to date, while 4 cases were seen in the standard frequency group. Thus, preliminary evidence suggests that less frequent dosing of natalizumab may be a safer, yet highly effective approach that also reduces the cost of this very expensive therapy by up to 50%.

4. Off-label use of DMTs for MS.

Presently, the main driver of MS costs is the direct costs for the DMTs,2,35 whose sales have more than doubled in the last few years.2 The average annual DMT price in the United States now exceeds $60,000 per patient-year.2,e1 A highly effective and significantly less expensive alternative for relapse suppression in MS is rituximab, a monoclonal, anti-CD20 antibody that is FDA-approved for treatment of certain malignancies (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) and autoimmune conditions (rheumatoid arthritis and others). Rituximab's impressive efficacy in relapsing-remitting MS was demonstrated in HERMES, a randomized clinical trial,36 and confirmed in 2 other trials,37,38 numerous observational studies,e8,e9 and the authors' personal experience.e10 A recent Swedish study comparing fingolimod vs rituximab in patients with relapsing MS who switched from natalizumab because of JC virus antibody positivity showed superiority of rituximab over fingolimod regarding both efficacy (relapses in 1.8% of rituximab-treated patients vs 17.6% on fingolimod; hazard ratio of 0.10) and safety (5.3% adverse event rate in rituximab patients vs 21.1% for fingolimod; hazard ratio of 0.25 in favor of rituximab).39

At the Rocky Mountain MS Center at the University of Colorado, we infuse rituximab 1,000 mg once and repeat with 500 mg IV every 6 months thereafter (unless there is reconstitution of CD20 cells, in which case we use 1,000 mg every 6 months). While costs vary by location and may change over time, the current cost for 1,500 mg spread over 2 doses, including the infusions themselves, is approximately $20,000 at a Walgreen's infusion center in Colorado near our institution, well below the average wholesale prices, or wholesale acquisition costs of the standard DMTs.2 It should also be noted that the above dosing strategy utilizes 50% or less of rituximab compared to the standard rheumatoid arthritis dosing of this drug (1 g 4 times a year).

A partially humanized version of rituximab, ocrelizumab, completed 4 phase II and III trials for relapsing and primary progressive MS. The 2 phase III trials of ocrelizumab in relapsing MS were reported at the 2015 ECTRIMS (European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis) meeting, and showed 46% reductions in annualized relapse rates and 95% reductions in new enhancing lesions in comparison to thrice weekly interferon beta-1a.e11 The placebo-controlled trial of ocrelizumab for primary progressive MS became the first primary progressive MS trial to meet its primary endpoint in reducing disability.e12 Its predecessor, a 2-year trial of rituximab vs placebo in primary progressive MS, was overall negative, but participants younger than 51 years and with enhancing lesions on their baseline brain MRI had a significant reduction in likelihood of sustained disease progression.e13 Ocrelizumab's maker has filed for FDA and other regulatory approvals for relapsing and progressive forms of MS in 2016 and is expected to receive a decision by January 2017. In our view, rituximab has 2 important advantages over ocrelizumab in relapsing MS: an established long-term safety record (an estimated 312,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis alone were treated with rituximab since its approval in 1997 [Genentech, data on file]), and a considerably lower projected price. Counting a phase II trial of another anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody, the completely humanized ofatumumab,e14 there are now 8 successful phase II and III studies supporting the use of anti–B cell therapy in MS. The time has come for insurance companies to routinely approve payment for the highly efficacious anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapy in MS, presently as rituximab.

While rituximab has the most evidence in support of off-label use in MS, other agents merit mention as well. Leflunomide is a readily available and inexpensive generic drug. Upon ingestion, leflunomide is almost entirely converted into teriflunomide, a moderately effective FDA-approved agent for relapsing-remitting MS.e15 As such, leflunomide has been used off-label for MS, although, to our knowledge, no studies of this drug in MS have been published. Monthly cost of leflunomide ranges from $24.85 to $65.68 (GoodRx.com), well below the cost of teriflunomide marketed as Aubagio (Sanofi Genzyme, Cambridge, MA). A head-to-head comparison of leflunomide with teriflunomide would be instructive. Other oral generic immunosuppressants, such as azathioprinee16 and methotrexate,e17 have a long history in MS, but are regarded as much less efficacious for relapse prevention as the newer agents, such as natalizumab or rituximab.

5. Should DMTs be continued indefinitely?

The question posed in the section title cannot be answered at present. All clinical trials that led to FDA approval of DMTs for relapsing MS typically had an age cutoff of 55 years or younger. Studies in progressive MS, often including those up to age 60 or 65, have generally been negative, unless one looks at subanalyses by age or recent inflammatory disease activity (relapses or enhancing lesions). The subanalyses show that younger patients with recent active inflammation do appear to benefit, regardless of placement into a “relapsing” or “progressive” phenotype category.e13,e18 Thus, while it is clear that younger patients with recent inflammatory disease activity benefit from presently available DMTs, it is not clear whether the same is true in older patients without recent inflammatory activity.

Discontinuation of interferon beta-1ae19,e20 or natalizumab32,33 in patients with highly active disease before therapy leads to disease reactivation within months of stoppage. But in older patients, who are at lower risk of relapsese21 and new enhancing lesions,e22 or in patients with no relapses or inflammatory MRI activity for prolonged periods, the benefits of continuing relapse suppressive therapies are uncertain. A recent observational study compared the risk of relapse and disease progression among patients with no relapses for 5 years or more, some of whom stopped DMT and others who continued on DMT.40 The 2 groups were propensity score–matched from a large MS database, MSBase. Their average age was 45 years. No difference in relapse rate was observed between the 2 groups, suggesting that stopping DMT in a nonrelapsing patient in this context does not increase risk of subsequent relapses. However, disability progression rates were higher among patients who stopped DMT. This difference was largely attributable to faster rate of progression among a subset of stoppers with no prebaseline disease progression compared to stayers with no prebaseline disease progression. Thus, it is unknown whether continuation of DMT in the older, nonrelapsing patients is warranted. The uncertainty provides justification, perhaps even an imperative, to conduct a randomized discontinuation trial,e23 in which some patients are randomized to continue on treatment and others to stop therapy. Such trials have been successfully conducted in oncology,e24 rheumatoid arthritise25 and other fields, but not in MS. We have recently received funding to conduct a randomized discontinuation trial in MS.e26 The 2-year, multicenter trial is scheduled to open enrollment in early 2017 for 300 patients who are 55 and older and have had no relapses or new MRI activity for at least 5 years while maintained on DMT. The results of the trial should help patients and clinicians make an informed decision as to whether and when it may be safe to stop DMT.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinical trial agendas in MS are, to a large extent, set by the pharmaceutical industry. In this article, we argue for greater clinician involvement in shaping the clinical research agenda for our field, with special emphasis on developing, and bringing to mainstream clinical practice, strategies that may decrease costs while enhancing the quality of care. We identified a number of possible therapeutic strategies that make medical and economic sense, including alternative dosing of FDA-approved DMTs; off-label use of highly effective relapse suppressants; customizing treatment of relapses; performing a randomized DMT discontinuation trial; and improving specificity of MRI criteria for MS and development of alternative biomarkers to enhance diagnostic accuracy (table). Some of these strategies do not, as yet, have sufficiently high level of evidence, and we advocate for high-quality research that would put these cost-effective approaches on a firm empiric basis.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- DMT

disease-modifying therapy

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PML

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

- UBO

unidentified bright object

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

Editorial, page 1532

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ilya Kister: study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision. John R. Corboy: study concept and design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURE

I. Kister served on scientific advisory board for Biogen Idec and Genentech, and received research support from Guthy-Jackson Charitable Foundation, National Multiple Sclerosis Society (NMSS), Biogen Idec, Serono, Genzyme, and Novartis. J. Corboy served as principal investigator on trials sponsored by Sun Pharma and NMSS, received research grants from NMSS, DioGenix, PCORI, served as consultant to Novartis, Genentech, and Teva Neuroscience, received honoraria from PRIME CME and medico-legal work, and serves as Editor of Neurology® Clinical Practice. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ney JP, Johnson B, Knabel T, Craft K, Kaufman J. Neurologist ambulatory care, health care utilization, and costs in a large commercial dataset. Neurology 2016;86:367–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, Whitham RH. The cost of multiple sclerosis drugs in the US and the pharmaceutical industry: too big to fail? Neurology 2015;84:2185–2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langer-Gould AM, Anderson WE, Armstrong MJ, et al. . The American Academy of Neurology's top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology 2013;81:1004–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mattson DH, Corboy JR, Larson R, et al. . The American Academy of Neurology's top five choosing wisely recommendations. Neurology 2013;81:1022–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solomon AJ, Weinshenker BG. Misdiagnosis of multiple sclerosis: frequency, causes, effects, and prevention. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 2013;13:403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon AJ, Klein EP, Bourdette D. “Undiagnosing” multiple sclerosis: the challenge of misdiagnosis in MS. Neurology 2012;78:1986–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmosino MJ, Brousseau KM, Arciniegas DB, Corboy JR. Initial evaluations for multiple sclerosis in a university multiple sclerosis center: outcomes and role of magnetic resonance imaging in referral. Arch Neurol 2005;62:585–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boster A, Caon C, Perumal J, et al. . Failure to develop multiple sclerosis in patients with neurologic symptoms without objective evidence. Mult Scler 2008;14:804–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly SB, Chaila E, Kinsella K, et al. . Using atypical symptoms and red flags to identify non-demyelinating disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012;83:44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakamura M, Morris M, Cerghet M, Schultz L, Elias S. Longitudinal follow-up of a cohort of patients with incidental abnormal magnetic resonance imaging findings at presentation and their risk of developing multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care 2014;16:111–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Tyler KL. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy complicating treatment with natalizumab and interferon beta-1a for multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2005;353:369–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mistry N, Abdel-Fahim R, Samaraweera A, Mougin O, Tallantyre E, Tench C. Imaging central veins in brain lesions with 3-T T2*-weighted magnetic resonance imaging differentiates multiple sclerosis from microangiopathic brain lesions. Mult Scler Epub 2015 Dec 10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Giorgio A, Stromillo ML, Rossi F, et al. . Cortical lesions in radiologically isolated syndrome. Neurology 2011;77:1896–1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Absinta M, Rocca MA, Colombo B, et al. . Patients with migraine do not have MRI-visible cortical lesions. J Neurol 2012;259:2695–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beck RW, Cleary PA, Anderson MM Jr, et al. . A randomized, controlled trial of corticosteroids in the treatment of acute optic neuritis. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. N Engl J Med 1992;326:581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Page E, Veillard D, Laplaud DA, et al. . Oral versus intravenous high-dose methylprednisolone for treatment of relapses in patients with multiple sclerosis (COPOUSEP): a randomised, controlled, double-blind, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2015;386:974–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenewould G, Hundt H, Luus H, et al. . Absolute bioavailability of new high dose methylprednisolone tablet formulation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994;32:652–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filippini G, Brusaferri F, Sibley WA, et al. . Corticosteroids or ACTH for acute exacerbations in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD001331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lublin FD, Baier M, Cutter G. Effect of relapses on development of residual deficit in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2003;61:1528–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirst C, Ingram G, Pearson O, Pickersgill T, Scolding N, Robertson N. Contribution of relapses to disability in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2008;255:280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roed HG, Langkilde A, Sellebjerg F, et al. . A double-blind, randomized trial of IV immunoglobulin treatment in acute optic neuritis. Neurology 2005;64:804–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soransen PS, Haas J, Sellebjerg F, et al. . IV immunoglobulins as add-on treatment to methylprednisolone for acute relapses in MS. Neurology 2004;63:2028–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weinshenker BG, O'Brien PC, Petterson TM, et al. . A randomized trial of plasma exchange in acute central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease. Ann Neurol 1999;46:878–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lalive PH, Neuhaus O, Benkhoucha M, et al. . Glatiramer acetate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: emerging concepts regarding its mechanism of action. CNS Drugs 2011;25:401–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan O, Perumal J, Caon C, et al. . Glatiramer acetate 20 mg subcutaneous twice-weekly versus daily injections: results of a pilot, prospective, randomized, and rater-blinded clinical and MRI 2-year study in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2009;15(suppl 2):S249–S250. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Flechter S, Kott E, Steiner-Birmanns B, Nisipeanu P, Korczyn AD. Copolymer 1 (glatiramer acetate) in relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis: open multicenter study of alternate-day administration. Clin Neuropharmacol 2002;25:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Novartis AG. GILENYA prescribing information. Available at: http://www.pharma.us.novartis.com/product/pi/pdf/gilenya.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- 28.Tanaka M, Tanaka K. Dose reduction therapy of fingolimod for Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis: 24-month experience. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol 2014;5:383–384. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamout BI, Zeineddine MM, Sawaya RA, Khoury SJ. Safety and efficacy of reduced fingolimod dosage treatment. J Neuroimmunol 2015;285:13–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ClinicalTrials.gov. MS study evaluating safety and efficacy of two doses of fingolimod versus Copaxone. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01633112. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- 31.Wipfler P, Harrer A, Pilz G, et al. . Natalizumab saturation: biomarker for individual treatment holiday after natalizumab withdrawal? Acta Neurol Scand 2014;129:e12–e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman M, Cree BA, De Sèze J, et al. . Radiologic MS disease activity during natalizumab treatment interruption: findings from RESTORE. J Neurol 2015;262:326–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kappos L, Radue EW, Comi G, et al. . Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology 2015;85:29–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. . Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:885–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens GM, Olvey EL, Skrepnek GH, Pill MW. Perspectives for managed care organizations on the burden of multiple sclerosis and the cost-benefits of disease-modifying therapies. J Manag Care Pharm 2013;19(1 suppl A):S41–S53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauser SL, Waubant E, Arnold DL, et al. . B-cell depletion with rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:676–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bar-Or A, Calabresi PA, Arnold D, et al. . Rituximab in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 72-week, open-label, phase I trial. Ann Neurol 2008;63:395–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naismith RT, Piccio L, Lyons JA, et al. . Rituximab add-on therapy for breakthrough relapsing multiple sclerosis: a 52-week phase II trial. Neurology 2010;74:1860–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alping P, Frisell T, Novakova L, et al. . Rituximab versus fingolimod after natalizumab in multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol 2016;79:950–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al. . Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry Epub 2016 Jun 13. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2016-313760. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.