Abstract

Magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles, composed of a plasmonic layer and a magnetic core, have been widely shown as promising contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) applications. However, their application in low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LFNMR) research remains scarce. Here we synthesised γ-Fe2O3/Au core/shell (γ-Fe2O3@Au) nanoparticles and subsequently used them in a homemade, high-Tc, superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) LFNMR system. Remarkably, we found that both the proton spin–lattice relaxation time (T1) and proton spin–spin relaxation time (T2) were influenced by the presence of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. Unlike the spin–spin relaxation rate (1/T2), the spin–lattice relaxation rate (1/T1) was found to be further enhanced upon exposing the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles to 532 nm light during NMR measurements. We showed that the photothermal effect of the plasmonic gold layer after absorbing light energy was responsible for the observed change in T1. This result reveals a promising method to actively control the contrast of T1 and T2 in low-field (LF) MRI applications.

It is well known that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a powerful, non-invasive technique that has been widely applied to the clinical diagnosis of diseases. However, the quality of magnetic resonance (MR) images is the key for early detection and precise location of infected tissues. MRI is basically based on the measurement of the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) signal of water protons. The contrast of MRI is highly dependent on proton density, proton spin–lattice relaxation time (T1) and proton spin–spin relaxation time (T2). With the aim of improving the image contrast, the so-called contrast agents (CAs) are frequently used in MRI. CAs are generally suspensions of paramagnetic or superparamagnetic nanoparticles, which do not generate NMR signals but influence the relaxation time of nearby protons by altering local magnetic fields. Because of their unique superparamagnetic characteristics, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) are commonly used as contrast enhancement agents1,2,3 in MRI applications. Superparamagnetic materials generally exhibit stronger relaxation effects per amount of iron than ferromagnetic particles4.

Recently, magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles (i.e. nanoparticles simultaneously showing magnetic and plasmonic characteristics) have become a hot topic of research. Magnetoplasmonic particles (e.g. gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles) generally consist of a precious metal layer along with a magnetic moiety. The magneto-optical activity of magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles has been shown to be greatly enhanced by the plasmon resonance effect5. Because of the good biocompatibility6, magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles have also been used in biosensor system7, hyperthermia8,9,10 and MRI10,11,12 applications.

Superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID)-based low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LFNMR) and LFMRI are compelling tools because of their specific advantages13. Compared with traditional high-field (HF) systems (magnetic field >1 Tesla), SQUID-based LFNMR devices13 are less expensive and have lower operational costs, lower fringe fields, fewer MR artefacts, unique contrast and less energy deposition in tissues. In addition, several groups have demonstrated that LFMRI, either as a standalone technique or integrated with magnetoencephalography (MEG), can successfully image the anatomy of the human brain14,15,16. Espy’s group at Los Alamos National Lab claimed that LFMRI devices are potentially introduced in battlefield scenarios and in developing countries to save lives17. Thus, it is expected that LFMRI is progressively introduced as a common clinical technique in the future. However, to satisfy clinical requirements, some characteristics of LFNMR or LFMRI such as signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and resolution still need to be improved. Therefore, CAs have been used in LFMRI to enhance image contrast18,19. On the other hand, gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles had been reported that they are a T2 contrast agent with high efficacy in the high field MRI20. However, the study on the gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles as a CA in the low field is still seldom. Here we synthesised γ-Fe2O3/Au core/shell (γ-Fe2O3@Au) nanoparticles and subsequently used them in a homemade, high-Tc, SQUID-based LFNMR system with the aim of studying the effect of magnetoplasmonic nanoparticles over the proton NMR relaxation time, while maintaining in LF regimes. The details of our homemade, high-Tc, SQUID-based LFNMR system can be found elsewhere21. We found that both T1 and T2 were affected by the presence of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. Furthermore, the spin–lattice relaxation rate (1/T1) and spin–spin relaxation rate (1/T2) varied with the concentration of nanoparticles. Remarkably, unlike 1/T2, 1/T1 was further enhanced under exposure of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles to 532 nm light, thereby revealing a promising method to actively control the contrast of T1 and T2 images during NMR measurements.

Results and Discussions

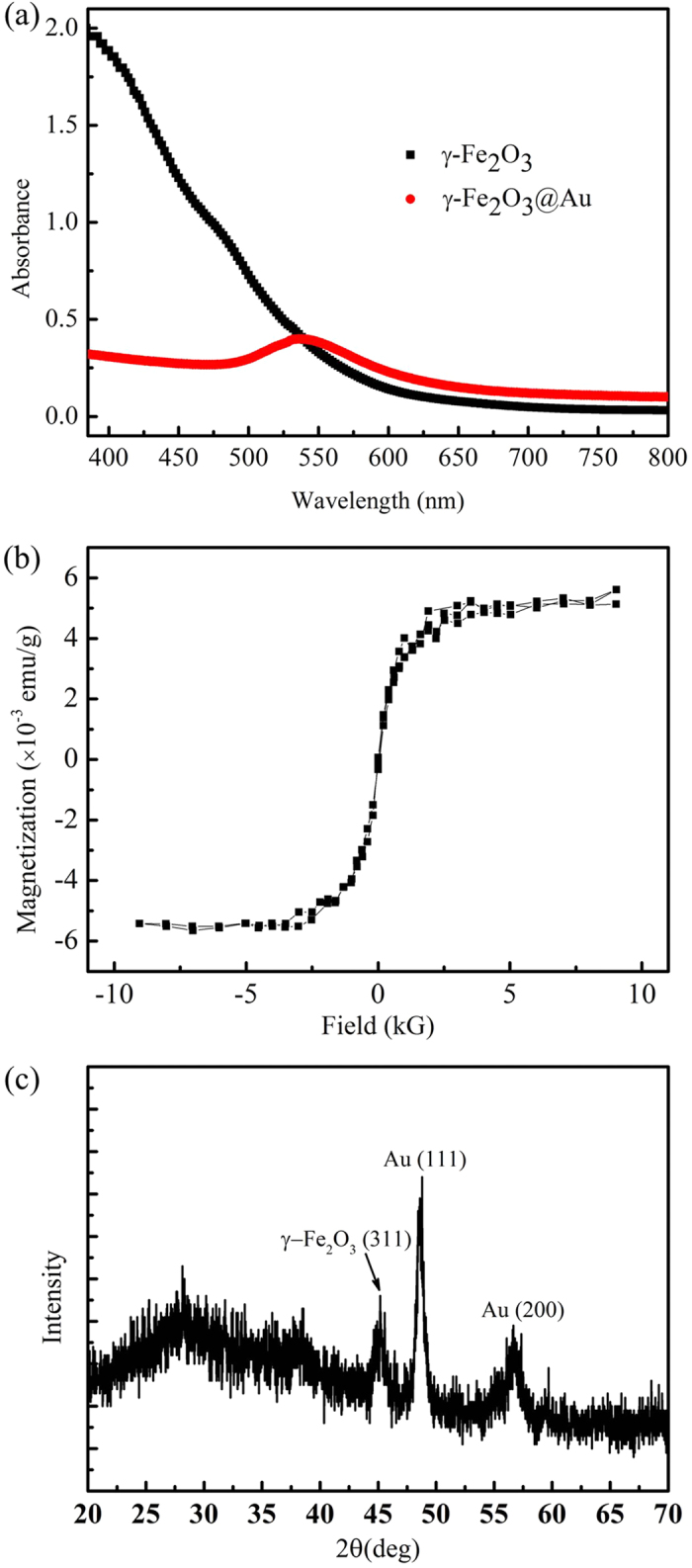

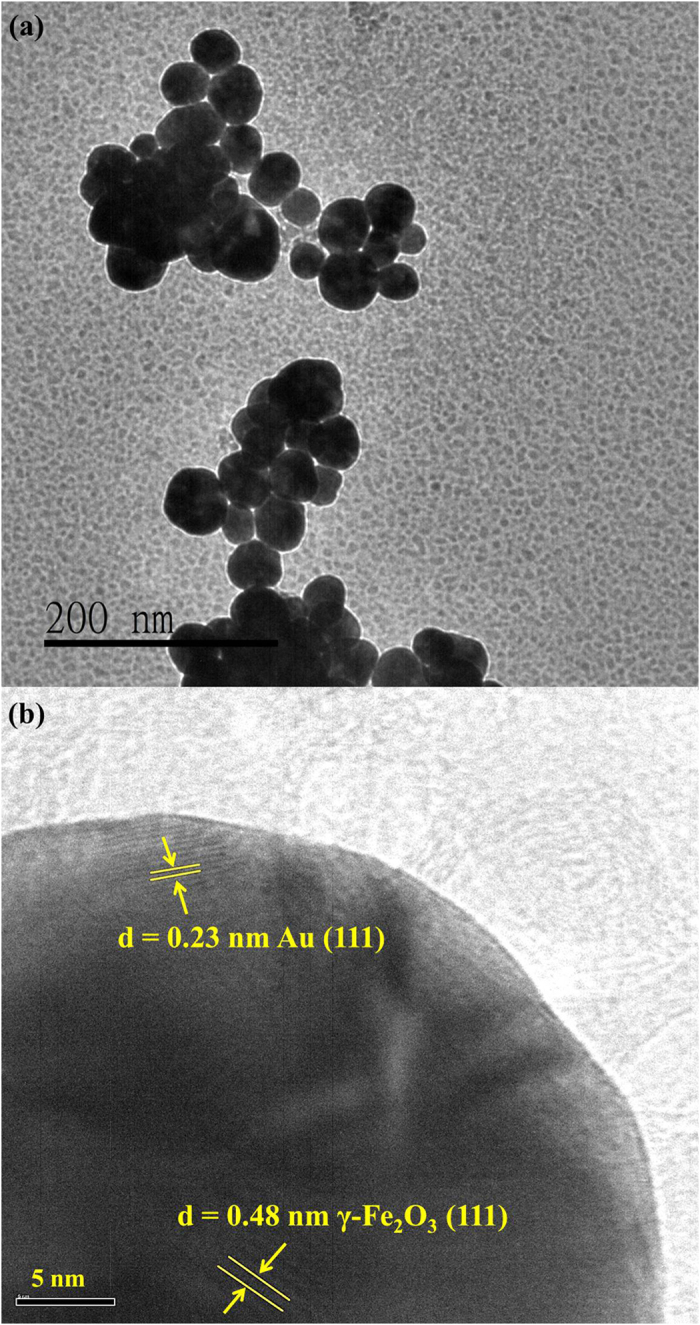

The average hydrodynamic size (i.e. diameter) of the synthesised γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles, determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Nanotrac-150, Microtrac), was 28.38 ± 6.26 nm. To increase the reliability of particle size, the average hydrodynamic size of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles was calculated from the DLS measurement data of ten samples. Figure 1a shows the UV–Vis absorption spectrum of both γ-Fe2O3 and γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. A characteristic plasmon peak at 536 nm, arising from the contribution of localised surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) of the Au shell, can be clearly observed in the case of hybrid nanoparticles. Figure 1b shows the hysteresis curve of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles measured by a SQUID magnetic property measurement system (MPMS, Quantum Design, Inc) at 300 K. The hysteresis curve of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles is characteristic of superparamagnetic materials with a saturation field of 2500 Gauss. Figure 1c is the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern (LabX XRD-6000, Shimadzu; iron−K radiation 0.1936 nm) of the synthesised γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. The XRD pattern shows peaks corresponding to known lattice planes of Au and γ-Fe2O3 and verifies that the synthesised nanoparticles contain Au and γ-Fe2O3 phases. Furthermore, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) (JEM-2010, JEOL Co. Ltd) was used to confirm the structure of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. Figure 2a is a low-magnification TEM image of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles and it shows that γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles are nearly spherical with a diameter of approximately 30~50 nm. A magnified TEM image (Fig. 2b) reveals two different crystal structures, that is, γ-Fe2O3 (111) in the core and Au (111) near the surface, thereby confirming the core–shell nature of the synthesised γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles.

Figure 1.

(a) UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the γ-Fe2O3 and γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. The plasmonic absorption peak of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles is approximately 536 nm. (b) Hysteresis curve of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles measured by the SQUID MPMS system at 300 K. (c) The powder XRD pattern of the synthesised γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles.

Figure 2. HRTEM images of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles.

(a) A low-magnification TEM image of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. (b) Locally magnified image of a γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticle. The Au shell and γ-Fe2O3 core crystal structures are observed.

Our homemade, high-Tc, SQUID-based LFNMR system was used to investigate the effect of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles over T1 and T2 proton relaxation times. The LFNMR measurements were performed by utilizing a pulsed pre-polarisation magnetic field of 70 mT and a measuring field of 100 μT. However, in this experiment, one should note that the effective background fields of T1 and T2 relaxations are different because of the different NMR measurement sequences. The details on the measurement sequences of T1 relaxation22 and T2 relaxation23 can be found elsewhere22,23. The volume of experimental sample was 1 mL. With the aim of quantifying the contribution of LSPR effect of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles to the global proton NMR signal, the sample was irradiated with 532 nm green laser light (100 μW power) via an optical fibre. The whole measurement process was performed at a stable temperature of 298 K, as confirmed by measuring the temperature before and after the irradiation.

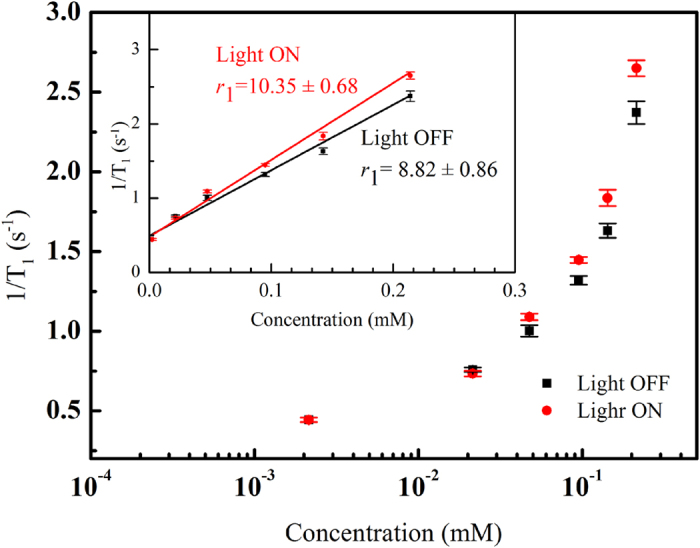

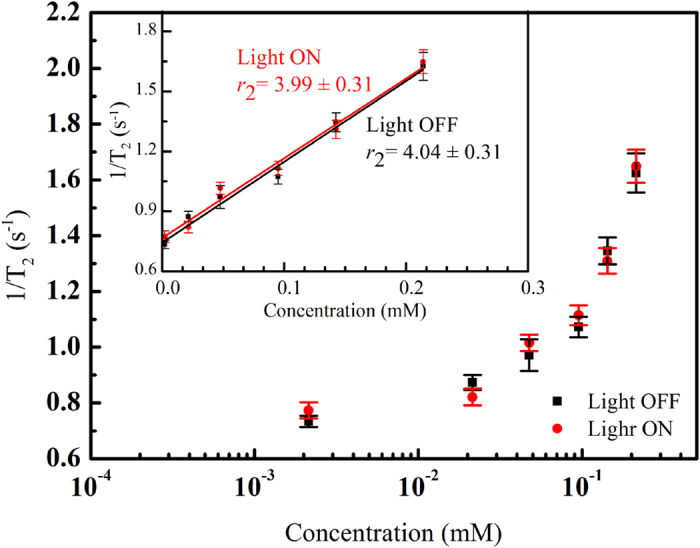

Figures 3 and 4 show 1/T1 and 1/T2, respectively, as a function of iron concentration in an aqueous suspension of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles (1 mL) in the presence and absence of light irradiation. The number of replicates for all the measurements was 10, and detailed data (expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean, SEM) are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. As can be clearly seen, 1/T1 changed upon light irradiation, with this variation being statistically significant (P < 0.05, t-test calculation) at iron concentrations higher than 0.048 mM. Remarkably, the longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles was enhanced as a result of light exposure (10.3 vs 8.81 mM−1 s−1). Conversely, 1/T2 was found to be unaffected by light irradiation regardless of the ion concentration because the variances of this parameter were not statistically significant in all cases. In addition, the transverse relaxivity (r2) was found to be nearly unchanged (approximately 4.0 mM−1 s−1) with irradiation conditions.

Figure 3. Spin–lattice relaxation rate (1/T1) as a function of iron concentration in a 1 mL aqueous solution of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles in the presence and absence of light irradiation.

The insert shows the longitudinal relaxivity of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. The values are presented as the mean ± SEM after 10 measurements.

Figure 4. Spin–spin relaxation rate (1/T2) as a function of iron concentration of a 1 mL γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles aqueous solution in the presence and absence of light irradiation.

The insert shows the transverse relaxivity of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. The values are also presented as the mean ± SEM after 10 measurements.

Table 1. Spin–lattice relaxation rate (1/T1) of 1 mL γ-Fe2O3@Au aqueous solution with and without light irradiation.

| 1/T1 (s−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron concentration (mM) | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.095 | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.0021 |

| Light OFF | 2.372 ± 0.071 | 1.631 ± 0.045 | 1.320 ± 0.027 | 1.003 ± 0.036 | 0.758 ± 0.014 | 0.444 ± 0.013 |

| Light On | 2.651 ± 0.050 | 1.835 ± 0.051 | 1.447 ± 0.019 | 1.090 ± 0.020 | 0.734 ± 0.017 | 0.444 ± 0.014 |

| P-value | 0.0016 | 0.0032 | 0.0005 | 0.0379 | 0.1693 | 0.4950 |

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM from 10 measurements. The P-value is based on single-trail paired t-test calculation.

Table 2. Spin–spin relaxation rate (1/T2) of 1 mL γ-Fe2O3@Au aqueous solution with and without light irradiation.

| 1/T2 (s−1) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iron concentration (mM) | 0.21 | 0.14 | 0.095 | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.0021 |

| Light OFF | 1.625 ± 0.086 | 1.345 ± 0.059 | 1.072 ± 0.045 | 0.971 ± 0.069 | 0.873 ± 0.032 | 0.734 ± 0.025 |

| Light On | 1.648 ± 0.073 | 1.309 ± 0.056 | 1.115 ± 0.044 | 0.998 ± 0.042 | 0.822 ± 0.036 | 0.773 ± 0.036 |

| P-value | 0.4197 | 0.3357 | 0.2591 | 0.3765 | 0.1521 | 0.2105 |

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM from 10 measurements. The P-value is based on single-trail paired t-test calculation.

We speculate that the photothermal effect of the plasmonic gold layer under light energy absorption could mainly account for the observed change in T1. The plasmonic photothermal therapy based on gold nanoparticles has been widely studied as a non-invasive cancer treatment24. The special plasmonic characteristics of gold nanoparticles allow photon light energy to be effectively absorbed and subsequently converted to heat. It is well known that temperature affects the proton spin relaxation. We previously found 1/T1 and 1/T2 proton relaxation rates to decrease with temperature in a magnetic fluid as a result of the enhanced Brownian motion of MNPs25. Therefore, the enhancement of 1/T1 relaxation rate cannot be attributed to the temperature increasing by laser irradiation. Moreover, here we ensured constant sample temperature using very-low-power laser irradiation (100 μW) during the experiment, although it seems that this energy is still high enough to influence the motion of magnetic γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles. As indicated above, we did not observe variation of T2 under light irradiation. It means that the light irradiation does not induce the temperature fluctuation in the sample.

On the other hand, T1 is dominated by the interaction between the proton spin and the surrounding lattice. The relaxation of water protons mainly depends on the dipolar coupling between the magnetic moments of water protons and magnetic particles26. Zhou et al.27 showed that the main contribution of the T1 contrast of magnetic nanoplates is the chemical exchange on the iron-rich Fe3O4(111) surfaces, which happens in the innershpere regime. They also showed that surface coating layer of nanoplates will hinder the chemical exchanges between the surrounding protons and surface iron metals. Referring to Zhou’s work, we think that the T1 shortening effect in our system is due to the outersphere translational diffusion of protons because the gold layer of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles would hinder the chemical exchange happening in the innersphere regime. We inferred that the motion of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles became more active after light irradiation. Thus, a greater energetic motion of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles would increase the collision rate with surrounding water protons. Energetic collision would shorten the distance between the magnetic moments of water protons and the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles and enhance their correlation. Increasing collision rate would also reduce the effective diffusion length of outersphere water protons and hence increase the diffusion correlation time. The enhanced correlation and the increased diffusion correlation time both facilitate the proton spins to effectively release their rf pulse magnetic energy back to the surrounding and shorten T1 after light irradiation.

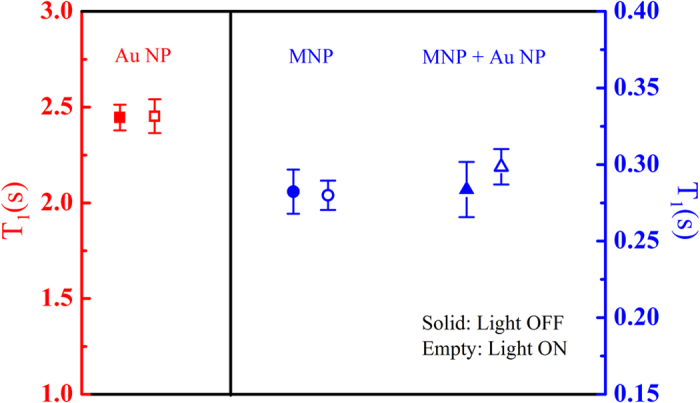

To confirm our assumption, we measured T1 of aqueous solutions containing Au nanoparticles, Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles and a mixture of Au and Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Table 3) under light irradiation at a constant temperature (i.e. temperature was unchanged during irradiation). The iron and gold concentrations in the solutions are 0.106 mM and 0.13 mM, respectively. The gold concentration is twice the gold concentration of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles with the same iron concentration. As shown in Fig. 5, T1 values remained constant after light irradiation for the three samples. In the case of light-absorbing Au nanoparticles, the low light intensity used prevented this sample from heating, thereby leaving T1 unaltered. In the case of the sample Fe3O4 nanoparticles, T1 is likely remained constant after irradiation because MNPs do not intrinsically absorb light energy. In the case of the sample containing a mixture of nanoparticles, both Au and magnetic entities were independently suspended in the solution, leading to ineffective motion excitement of MNPs by light-absorbing Au nanoparticles. Therefore, the correlation between water protons and MNPs cannot be effectively enhanced by light irradiation, and the T1 relaxation time thus remained unchanged. The results showed that even the solution with higher concentration of Au nanoparticle, it still cannot induce the enhancement of 1/T1 relaxation rate under light irradiation. Only the core–shell γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles can effectively enhance the 1/T1 relaxation rate under light irradiation. These results strongly support our assumptions and prove that the unique core–shell structure of the γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles allows control of T1 by light irradiation within the LFNMR system.

Table 3. T1 values of Au nanoparticles, Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles and mixture of Au and Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (aqueous solutions) with and without light irradiation.

| T1 (s) | Au nanoparticle | Magnetic nanoparticle | Magnetic nanoparticle + Au nanoparticle | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Off | On | Off | On | Off | On |

| Average | 2.447 | 2.453 | 0.282 | 0.280 | 0.284 | 0.299 |

| SEM | 0.067 | 0.088 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.018 | 0.011 |

| P-value | 0.469 | 0.247 | 0.448 | |||

The data are presented as the mean ± SEM from 10 measurements. The P-value is based on single-trail paired t-test calculation.

Figure 5. T1 values of the aqueous solutions containing Au nanoparticles (NP), Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles (MNP) and a mixture of Au and Fe3O4 MNP in the presence and absence of light irradiation.

The empty and solid symbols represent the data measured in the presence and absence of light irradiation, respectively. The data of Au NPs refer to the left axis, whereas the data of MNPs and the mixture of Au NPs and MNPs are represented in the right axis. These values are also presented as the mean ± SEM after 10 measurements.

In summary, we synthesised core–shell γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles to be used in LFNMR systems. We found that the presence of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles in the aqueous solution can effectively modify T1 and T2. In particular, T1 can be further altered by the irradiation with 532 nm light, and the alteration was produced by energetic motion of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles induced by a photothermal effect. Because a mixture of individual Au and MNPs was not effective in changing T1, we concluded that the unique magnetoplasmonic characteristics of γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles are responsible for this behaviour. This study thus offers a promising way to modulate the contrast of LFMRI devices by light irradiation with γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles as CAs.

Methods

Synthesis of the core–shell γ-Fe2O3@Au nanoparticles

FeCl3.6H2O and FeCl2.4H2O powders were initially dissolved in water (2:1). NaOH solution was then added into the ferric solution under vigorous stirring. Ferric ions were reduced to Fe3O4 magnetic particles, resulting in the formation of a black precipitate, which was washed twice with ultrapure water. A 0.1 M HNO3 solution was subsequently added to wash the Fe3O4 nanoparticles, and the resulting solution was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 20 min.

The precipitate was collected and re-dissolved in 0.01 M HNO3 at 90 °C–100 °C (water bath) under continuous stirring for 30 min and subsequently oxidised to γ-Fe2O3 to form a reddish brown colloidal solution. γ-Fe2O3 particles were collected by centrifugation (6,000 rpm, 20 min) and washed twice with ultrapure water.

The nanoparticle suspension was formed using a 36 mM tetramethylammonium hydroxide [TMAOH, N(CH3)4OH] solution at pH = 12. TMAOH dissociation results in the release of N(CH3)+ and OH− ions; the latter allow suspension by linking to the surface of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

The suspending solution of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles was diluted to 0.1 mM, and an equal volume of a 0.1 M sodium citrate (C6H5O7Na3.2H2O) aqueous solution was added. The resulting solution was stirred for at least 10 min, during which the citrate ion (C6H5O73−) replaced OH− on the surface of γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticle colloidal solution was subsequently diluted 20-fold to reach a 2.5 mM citrate salt concentration, and an equal volume of tetrachloroauric acid (1% HAuCl4) solution was prepared for iterative seeding process. The seeding process consisted of a slow addition of NH2OH·HCl and HAuCl4 in excess to the γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticle colloidal solution. This seeding process was repeated (seeding time higher than 10 s) four times, with at least a 10-min interval between iterations. This process allows Au3+ ions to reduce and subsequently link on the surface of the nanoparticles. The colour of the solution shifted from purple to deep pink as the Au layer was formed on the surface of the magnetic particles.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, K.-L. et al. Influence of magnetoplasmonic γ-Fe2O3/Au core/shell nanoparticles on low-field nuclear magnetic resonance. Sci. Rep. 6, 35477; doi: 10.1038/srep35477 (2016).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge financial support provided by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan under grants: MOST103-2112-M-005-005-MY3.

Footnotes

Author Contributions Conceived and designed the experiments: K.-L.C. Performed the experiments: K.-L.C., Y.-W.Y., J.-M.C., Y.-J.H., T.-L.H. and Z.-Y.D. Analyzed the data: K.-L.C. and Y.-W.Y. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: C.-H.W., S.-H.L. and L.-M.W. Wrote the paper: K.-L.C.

References

- Masotti A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of polyethylenimine-based iron oxide composites as novel contrast agents for MRI. Magn Reson Mater Phy. 22, 77–87 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casula M. F. et al. Magnetic resonance contrast agents based on iron oxide superparamagnetic ferrofluids. Chem. Mater. 22, 1739–1748 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z. et al. Octapod iron oxide nanoparticles as high-performance T2 contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Commun. 4, 2266 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephson L., Lewis J., Jacobs P., Hahn P. F. & Stark D. D. The effects of iron oxides on proton relaxivity. Magn. Reson. Imag. 6, 647 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain P. K., Xiao Y., Walsworth R. & Cohen A. E. Surface plasmon resonance enhanced magneto-optics (SuPREMO): Faraday rotation enhancement in gold-coated iron oxide nanocrystals. Nano Letters 9, 1644–1650 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling D. & Hyeon T. Chemical design of biocompatible iron oxide nanoparticle for medical applications. Small 9, 1450–1466 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang D. et al. Building nanospr biosensor systems based on gold magnetic composite nanoparticles. J. Nanosci. Nanotechno. 13, 5485–5492 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad F., Balaji G., Weber A., Uppu R. M. & Kumar C. S. Influence of gold nanoshell on hyperthermia of super paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (Spions). J. Phys. Chem. C Nanomater. Interfaces. 114, 19194–19201 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsherbini A. A. M., Saber M., Aggag M., EI-Shahawy A. & Shokier H. A. Laser and radiofrequency-induced hyperthermia treatment via gold-coated magnetic nanocomposites. Int. J. Nanomed. 6, 2155–2165 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoskins C. et al. Hybrid Gold-Iron Oxide Nanoparticles as a Multifunctional Platform for Biomedical Application. J. Nanobiotechnology 10, 27 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolensky E. D., Neary M. C., Zhou Y., Berquo T. S. & Pierre V. C. Fe3O4@Organic@Au: core-shell nanocomposites with high saturation magnetisation as magnetoplasmonic MRI contrast agents. Chem. Commun. (Camb). 47, 2149–2151 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umut E. et al. Optical & Relaxometric properties of organically coated gold-magnetite (Au-Fe3O4) hybrid nanoparticles for potential use in biomedical applications. J Magn. Magn. Mater. 324, 2373–2379 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Espy M., Matlashov A. & Volegov P. SQUID-detected ultra-low field MRI. J. Magn. Reson. 228, 1–15 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zotev V. S. et al. Microtesla MRI of the human brain combined with MEG. J. Mag. Reson. 194, 115–120 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnelind P. E. et al. Co-Registration of Interleaved MEG and ULF MRI Using a 7 Channel Low-Tc SQUID System. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 21, 456–460 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Vesanen P. T. et al. Hybrid ultra-low-field MRI and magnetoencephalography system based on a commercial wholehead neuromagnetometer, Magn. Reson. Med. 69, 1795–1804 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R., Battlefield MRI, 1663 The Los Alamos Science and Technology Magazine January, 22–26 (2015).

- Liao S. H., Yang H. C., Horng H. E. & Yang S. Y. Characterization of magnetic nanoparticles as contrast agents in magnetic resonance imaging using high-Tc superconducting quantum interference devices in microtesla magnetic fields. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 22, 025003 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Chen H. H. et al. Relaxation rates of protons in gadolinium chelates detected with a high-Tc superconducting quantum interference device in microtesla magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 108, 093904 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad T. et al. Gold-coated iron oxide nanoparticles as a T2 contrast agent in magnetic resonance imaging. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 12, 5132–5137 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. C. et al. Enhancement of nuclear magnetic resonance in microtesla magnetic field with prepolarization field detected with high-Tc superconducting quantum interference device. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 252505 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Liao S. H. et al. Characterizing the field-dependent T1-relaxation and imaging of ferrofluids using high-Tc superconducting quantum interference device magnetometer in low magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 123908 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. C. et al. Relaxation of biofunctionalized magnetic nanoparticles in ultra-low magnetic fields. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 043911 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. & El-Sayed M. A. Plasmonic photo-thermal therapy (PPTT). Alex J Med. 47, 1–9 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Yang H. C. et al. Temperature and concentration-dependent relaxation of ferrofluids characterized with a high-Tc SQUID-based nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 202405 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gossuin Y., Gills P., Hocq A., Vuong Q. L. & Roch A. Magnetic resonance relaxation properties of superparamagnetic particles. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 1, 299–310 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z. et al. Interplay between Longitudinal and Transverse Contrasts in Fe3O4 Nanoplates with (111) Exposed Surfaces. ACS Nano 8, 7976–7985 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]