Abstract

Background

The effect of decompressive laparotomy on outcomes in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome has been poorly investigated. The aim of this prospective cohort study was to describe the effect of decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome on organ function and outcomes.

Methods

This was a prospective cohort study in adult patients who underwent decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome. The primary endpoints were 28‐day and 1‐year all‐cause mortality. Changes in intra‐abdominal pressure (IAP) and organ function, and laparotomy‐related morbidity were secondary endpoints.

Results

Thirty‐three patients were included in the study (20 men). Twenty‐seven patients were surgical admissions treated for abdominal conditions. The median (i.q.r.) Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score was 26 (20–32). Median IAP was 23 (21–27) mmHg before decompressive laparotomy, decreasing to 12 (9–15), 13 (8–17), 12 (9–15) and 12 (9–14) mmHg after 2, 6, 24 and 72 h. Decompressive laparotomy significantly improved oxygenation and urinary output. Survivors showed improvement in organ function scores, but non‐survivors did not. Fourteen complications related to the procedure developed in eight of the 33 patients. The abdomen could be closed primarily in 18 patients. The overall 28‐day mortality rate was 36 per cent (12 of 33), which increased to 55 per cent (18 patients) at 1 year. Non‐survivors were no different from survivors, except that they tended to be older and on mechanical ventilation.

Conclusion

Decompressive laparotomy reduced IAP and had an immediate effect on organ function. It should be considered in patients with abdominal compartment syndrome.

Short abstract

Improves organ function

Introduction

Intra‐abdominal hypertension (IAH) is a clearly identified cause of organ dysfunction in patients who have had emergency abdominal surgery or suffered severe trauma1, 2, 3, 4. It is also being recognized increasingly in various other patients receiving intensive care after elective surgical procedures5, liver transplantation6, massive fluid resuscitation for extra‐abdominal trauma7, severe burns8 and aortic aneurysm repair9, 10. The presence of IAH on admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) is associated with the development of severe organ dysfunction, and the presence of IAH in the ICU is an independent predictor of mortality5, 11.

The clinical picture that results from sustained IAH with an intra‐abdominal pressure (IAP) of 20 mmHg or higher has been described as abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Although the pathophysiology of IAH is well understood12, 13, 14, the treatment of ACS remains challenging. Few non‐surgical options are available. IAH can be caused by intraperitoneal fluid accumulation, and percutaneous drainage15 may be a valid option in such situations. Gastric and rectal tubes have been used to drain air and gastrointestinal contents with some success, as have ultrafiltration, pain relief and muscular blocking agents14.

Surgical decompression of the abdomen, or decompressive laparotomy (DL), is the only available definitive treatment for ACS. Numerous case reports and case series have been published detailing results16, 17, 18, but the exact role of DL remains unclear. Most papers focus on the description of associated parameters such as airway pressure, central venous pressure or urinary output, rather than specifically looking at endpoints such as hospital mortality and organ function. Morbidity associated with DL for ACS has not been assessed prospectively in a large series.

The IAP threshold value for DL varies considerably in the available literature, and the influence of factors such as the interval between onset of organ dysfunction and DL itself on measured outcomes remains unclear. A more complete picture of DL as a treatment for IAH and ACS, beyond the performance of the procedure itself, could potentially lead to the identification of patients who would benefit most. The aims of this study were to describe the effects of DL for ACS on organ function, and the overall morbidity and mortality among patients in intensive care, and to identify factors associated with mortality.

Methods

This was a prospective multicentre observational study of the effects of DL on mortality and organ function. It was organized through WSACS – the Abdominal Compartment Society (http://WSACS.org). The study was approved by the ethics committee of Ghent University Hospital and similar committees at the individual participating hospitals. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient or their legal representative when required by local institutional regulations; in some participating hospitals a waiver for consent was granted.

Patients were eligible for inclusion in the study if they were aged 18 years or older, and were treated with DL for a diagnosis of ACS. Pregnancy and previous enrolment in the present study were the only exclusion criteria.

The primary endpoints of the study were all‐cause mortality at 28 days and 1 year after DL. Secondary endpoints were changes in organ function and laparotomy‐related morbidity.

Data collection

Relevant data were retrieved from the clinical notes and included preoperative parameters: age, sex, weight, height, date of hospital/ICU admission, admission diagnosis, and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) 2 scores. The cause of ACS, the time of diagnosis and treatment(s) for ACS, the surgical technique used for DL and the method of temporary abdominal closure were recorded.

IAP values were collected at baseline, in the days before DL, and at 2, 6, 12, 24, 72 and 168 h after laparotomy, when available. Organ dysfunction was assessed using the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score19. The SOFA score was recorded before DL, and at 6, 24, 72 and 168 h thereafter.

The duration of stay in the ICU and in hospital, and mortality at each time point was documented. Complications related to DL and open abdomen treatment were recorded.

Definitions

IAP was measured using intravesical pressure according to the WSACS guidelines14, 20. IAH was defined by a sustained IAP of 12 mmHg or higher. The diagnosis of ACS was defined by an IAP of 20 mmHg or above with new‐onset or deteriorating organ dysfunction. DL was defined as a laparotomy performed solely for ACS and aimed at reducing IAP.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are expressed as median (i.q.r.). The Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of median values, and the Friedman test or Wilcoxon matched‐pairs signed‐ranks test when appropriate. Proportions were compared using 2 × 2 tables and the χ2 or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate. Correlation between variables was analysed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. P < 0·010 was considered statistically significant, adjusting for multiple comparisons. Statistical analysis was done using SPSS® version 20.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Thirty‐three patients were included in the study, 20 of whom were men. Their median age was 61 (51–70) years. Median baseline APACHE II and SAPS 2 scores were 25·5 (20·0–31·8) and 57·0 (42·5–64·3) respectively. Median body mass index was 29·0 (25·2–35·1) kg/m2.

Most were surgical patients treated previously for abdominal conditions, and 27 of the 33 patients had primary ACS. Diagnoses leading to ACS are summarized in Table 1. Patients were included at the eight participating centres between 1 December 2009 and 31 December 2011; the number of patients included per centre ranged from two to 14.

Table 1.

Cause of abdominal compartment syndrome

| No. of patients | |

|---|---|

| Ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm | 6 |

| Abdominal sepsis | 5 |

| Abdominal trauma | 5 |

| Severe acute pancreatitis | 5 |

| Complicated abdominal surgery | 5 |

| Severe sepsis/septic shock | 4 |

| Cardiogenic shock | 2 |

| Abdominal haemorrhage | 1 |

Surgical procedure and temporary abdominal closure

Decompression in 30 patients was achieved through a midline laparotomy; other methods included subcostal incision (2) and subcutaneous linea alba fasciotomy (SLAF) (1). The procedure was performed in the operating theatre in 30 patients; the abdomen was decompressed in the ICU in the other three. In 17 patients a large volume of ascites was drained during the procedure (median 2000 (1000–3000) ml).

In 27 patients the DL was performed a median of 24·5 (8·3–75·3) h after ICU admission; this was at a median of 3 (1–9) h after the diagnosis of ACS. The remaining six patients were admitted to the ICU only after the DL had been done.

After DL, all but one patient (who was treated with SLAF) required temporary abdominal closure. A vacuum pack or a similar temporary abdominal closure technique was used in 20 patients; ten patients were treated with a negative‐pressure wound therapy device (combined with mesh‐mediated traction in 3), and two patients had a Bogota bag.

Effect on intra‐abdominal pressure and organ function

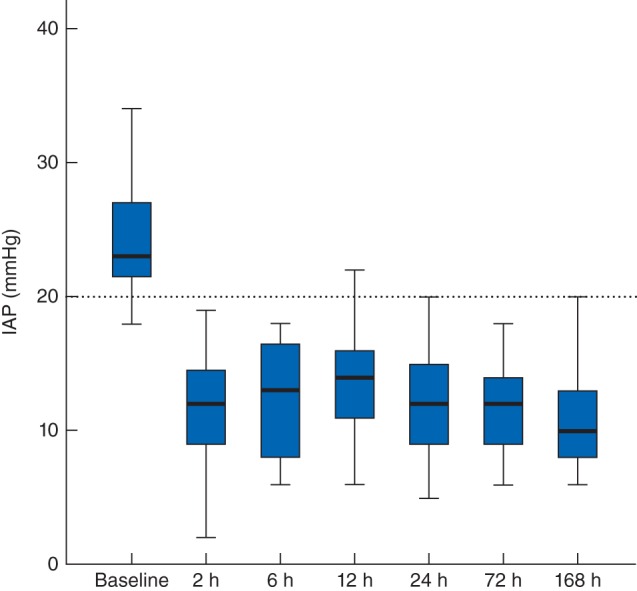

Median baseline IAP before DL was 23 (21–27) mmHg. After DL, it decreased significantly, with all subsequent measurements significantly lower than at baseline (all P < 0·001) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Intra‐abdominal pressure before and after decompressive laparotomy. Median values (bold line), i.q.r. (box) and total range (error bars) are shown. The dotted line indicates the threshold value for abdominal compartment syndrome

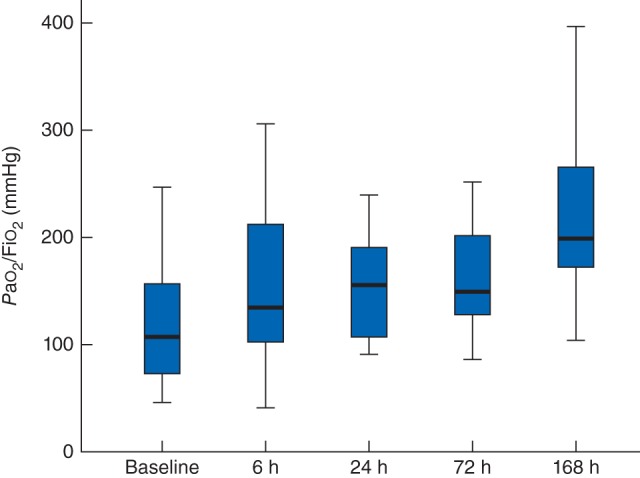

DL significantly improved oxygenation (expressed as the ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen) measured at the same time points (P < 0·001 for all measurements after DL compared with baseline) (Fig. 2). Median 2‐h urinary output at 6 and 24 h after DL was 68 (9–185) and 41 (5–180) ml respectively, compared with 23 (0–118) ml at baseline (P = 0·009 and P = 0·020). Five patients required renal replacement therapy (RRT) before undergoing DL; one of them did not require RRT after DL. RRT was initiated after DL in seven of the remaining 28 patients.

Figure 2.

Ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (Pao 2/Fio 2) at baseline and after decompressive laparotomy. Median values (bold line), i.q.r. (box) and total range (error bars) are shown

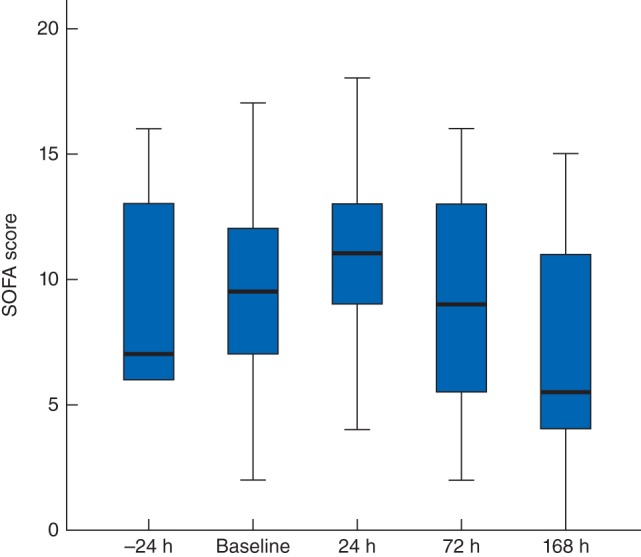

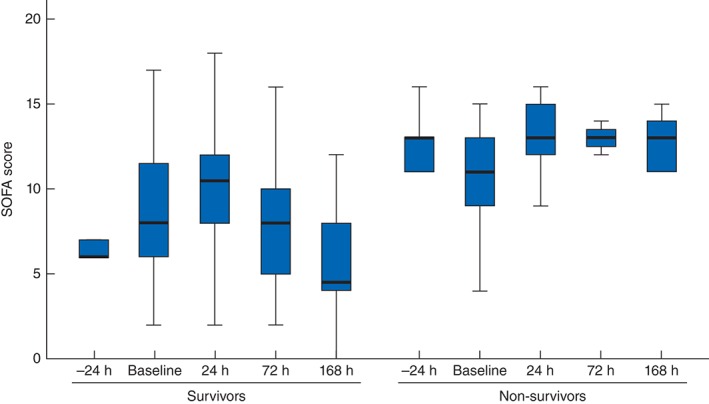

The median SOFA score before DL was 10 (7–12) and initially increased to 11 (8–13) at 24 h (P = 0·020 versus baseline), 9 (5–13) on day 3 (P = 0·871) and 6 (4–11) on day 7 (P = 0·098) (Fig. 3). The effect of DL on the SOFA score in survivors and non‐survivors is depicted in Fig. 4.

Figure 3.

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score before and after decompressive laparotomy. Median values (bold line), i.q.r. (box) and total range (error bars) are shown

Figure 4.

SOFA score after decompressive laparotomy in survivors and non‐survivors. Median values (bold line), i.q.r. (box) and total range (error bars) are shown

Complications

Eight patients (24 per cent) developed a total of 14 complications related to the open abdomen treatment: infection (4), recurrent ACS (2), bleeding (2), enteroatmospheric fistula (1) and abdominal wall hernia (5).

Outcomes

The abdomen could be closed primarily in 18 of the 33 patients. The median duration of open abdomen treatment was 7 (2–16) days. The abdomen was considered surgically closed at 1‐year follow‐up in all 18 surviving patients.

Overall, the 28‐day mortality rate was 36 per cent (12 of 33 patients). Deaths were due to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) in seven patients, intestinal ischaemia in two, septic shock in two and cardiac failure in one patient. The mortality rate increased to 55 per cent (18 of 33 patients) at 1‐year follow‐up, although four of these patients died within 40 days of DL. Causes of death were diverse and included MODS, cardiac arrest, septic shock and abdominal bleeding; no cause was specified in two patients.

Factors associated with mortality after decompressive laparotomy

At baseline, patients who did not survive the first 28 days after DL were no different from survivors, except that they tended to be older (63 (60–74) versus 53 (43–70) years; P = 0·046), and were more often on mechanical ventilation (12 of 12 versus 14 of 21 respectively; P = 0·027) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of survivors and non‐survivors after treatment with decompressive laparotomy

| Survivors (n = 21) | Non‐survivors (n = 12) | P † | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics and severity of illness | |||

| Age* | 53 (43–70) | 63 (60–74) | 0·046‡ |

| Sex ratio (M : F) | 12 : 9 | 8 : 4 | 0·719 |

| APACHE II score* | 24·5 (17·0–32·3) | 27·0 (22·3–31·8) | 0·454‡ |

| SAPS 2 score* | 57·0 (38·3–62·0) | 54·5 (46·0–65·0) | 0·434‡ |

| BMI (kg/m2)* | 29·6 (25·0–35·7) | 26·9 (25·1–30·4) | 0·289‡ |

| Organ function and support before decompressive laparotomy | |||

| SOFA score* | 8 (6–12) | 11 (9–14) | 0·200‡ |

| Pao 2/Fio 2 ratio* | 111 (63–177) | 150 (101–229) | 0·550‡ |

| Urinary output over 2 h (ml)* | 40 (12–127) | 5 (0–55) | 0·073‡ |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl)* | 1·71 (0·80–2·96) | 2·91 (1·31–3·32) | 0·367‡ |

| Mechanical ventilation | 14 | 12 | 0·027 |

| Renal replacement therapy | 2 | 3 | 0·242§ |

| ACS‐related factors | |||

| IAP before decompressive laparotomy (mmHg)* | 24 (22–30) | 22 (19–24) | 0·061‡ |

| Interval from ACS diagnosis to decompression (h)* | 3 (2–33) | 2 (1–6) | 0·981‡ |

| ACS type | 0·626§ | ||

| Primary | 17 | 10 | |

| Secondary | 4 | 2 | |

| Temporary abdominal closure | 0·148§ | ||

| None (SLAF) | 1 | 0 | |

| Bogota bag | 1 | 1 | |

| Vacuum pack or similar | 10 | 10 | |

| Vacuum‐assisted closure | 9 | 1 | |

Values are median (i.q.r.). APACHE, Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation; SAPS, Simplified Acute Physiology Score; BMI, body mass index; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; Pao 2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; Fio 2, fraction of inspired oxygen; ACS, abdominal compartment syndrome; IAP, intra‐abdominal pressure; SLAF, subcutaneous linea alba fasciotomy.

χ2 test, except

Mann–Whitney U test and

Fisher's exact test.

Discussion

This study found that the use of DL was effective in decreasing the IAP in patients with ACS, and resulted in immediate improvement of oxygenation and urinary output. The associated complication rate was low and the overall outcome better than reported previously.

The absolute reduction in IAP observed in this study is lower than reported previously, presumably owing to the relatively lower IAP at which DL was performed. The mean IAP was as high as 34·6 mmHg in a review16 reporting on experience dating from the 1990s and early 2000s. The lower threshold for DL in this study potentially reflects a more proactive approach to IAH/ACS. The fact that decompression was carried out at a lower IAP may have improved outcomes. In addition, the median interval of 24·5 h between ICU admission and DL suggests that physicians are no longer postponing DL until symptoms of organ dysfunction are intractable.

This contemporary study confirms the beneficial effect of timely DL on organ dysfunction that has been reported in previous publications. Although many studies suffer from methodological issues and most report on small patient numbers, several larger studies have now confirmed these early findings. Chiara and colleagues21 found that DL was effective in reducing IAP, and improving haemodynamics and urinary output, in 29 patients with primary ACS. Struck and co‐workers22 found a sustained improvement in oxygenation as well as static compliance after DL in 35 burned patients treated with ACS, who had a median IAP of 33 mmHg before DL.

Over time, the reported survival rate after DL has also improved. The mortality rate in a systematic literature review16 in 2006 exceeded 50 per cent, whereas recent figures are consistently lower. In 2013, Davis and colleagues23 reported a hospital mortality rate of 25 per cent among patients with severe acute pancreatitis who were treated with DL; this rate was comparable to that of patients who did not require DL. In a large cohort of more than 1000 patients who underwent emergency or elective surgery for aortic aneurysm, 2·8 per cent needed open abdomen treatment. Among these, 27 per cent died within 30 days, and 50 per cent within 1 year9.

This trend towards improved survival may be explained by several factors. As already mentioned, ACS may now be treated at an earlier stage; however, recent insights into the pathophysiology of both IAH and ACS and the related role of fluid overload, as well as improvements in haemodynamic and ventilatory management, may also have contributed. Finally, improvements in management of the open abdomen – previously considered a challenging condition24, 25 – and the focus on early abdominal closure to avoid subsequent complications26 undoubtedly contributed to the relatively low complication rates and low early mortality rates in the present study. Late mortality was significantly higher, a finding in line with the above‐mentioned studies.

The timing of DL is an important issue, although this could not be confirmed in the present study. Skoog and co‐workers27 studied the effect of DL on peritoneal metabolism at 4 h after inducing IAH (30 mmHg) in a porcine model. They found that early DL resulted in improved intestinal blood flow and could normalize the lactate/pyruvate ratio, a marker of intestinal hypoperfusion. Ke et al.28 reported that well timed DL was associated with lower mortality and improved organ function in an experimental model of severe acute pancreatitis and ACS. If DL was postponed for 12 h, compared with 6 or 9 h, more severe organ dysfunction ensued.

This study has a number of limitations. During enrolment, the number of DLs performed for ACS was lower than expected. This may have been due to improved conservative and proactive management of IAH that resulted in prevention of the development of ACS. There was also an increasingly used option to leave the abdomen open prophylactically after abdominal surgery for reasons not related specifically to ACS. The small number of patients in this prospective study also precluded multivariable analyses.

The WSACS used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) classification to update its guidelines for managing IAH and ACS, and published the recommendations in 201314. A review of the literature revealed that there were no randomized trials investigating the role of DL, but multiple case series. When the data from these studies were pooled, it was concluded that DL was very effective in reducing IAP, especially when it was high before decompression. Beneficial effects on organ function were also described, and led the experts to conclude that the use of DL to reduce IAP in critically ill adults with ACS compared with strategies that do not use DL is strongly recommended, although the available evidence is weak (GRADE 1D recommendation).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance of K. Sörelius, Department of Surgical Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden. This study was supported by the Clinical Trials Working Group of WSACS – the Abdominal Compartment Society. J.J.D.W. is a Senior Clinical Investigator at the Research Foundation Flanders.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Presented to the Annual Meeting of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine, Barcelona, Spain, September 2014; published in abstract form as Intensive Care Med 2014; 40(Suppl 1): S32–S33

References

- 1. Schein M, Ivatury R. Intra‐abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome. Br J Surg 1998; 85: 1027–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, Holcomb JB, Ware DN et al Secondary abdominal compartment syndrome is an elusive early complication of traumatic shock resuscitation. Am J Surg 2002; 184: 538–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ertel W, Oberholzer A, Platz A, Stocker R, Trentz O. Incidence and clinical pattern of the abdominal compartment syndrome after ‘damage‐control’ laparotomy in 311 patients with severe abdominal and/or pelvic trauma. Crit Care Med 2000; 28: 1747–1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ivatury RR, Porter JM, Simon RJ, Islam S, John R, Stahl WM. Intra‐abdominal hypertension after life‐threatening penetrating abdominal trauma: prophylaxis, incidence, and clinical relevance to gastric mucosal pH and abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma 1998; 44: 1016–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Malbrain ML, Chiumello D, Pelosi P, Bihari D, Innes R, Ranieri VM et al Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients: a multiple‐center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med 2005; 33: 315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Biancofiore G, Bindi ML, Romanelli AM, Boldrini A, Consani G, Bisà M et al Intra‐abdominal pressure monitoring in liver transplant recipients: a prospective study. Intensive Care Med 2003; 29: 30–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Balogh Z, McKinley BA, Cocanour CS, Kozar RA, Valdivia A, Sailors RM et al Supranormal trauma resuscitation causes more cases of abdominal compartment syndrome. Arch Surg 2003; 138: 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ivy ME, Atweh NA, Palmer J, Possenti PP, Pineau M, D'Aiuto M. Intra‐abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome in burn patients. J Trauma 2000; 49: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sorelius K, Wanhainen A, Acosta S, Svensson M, Djavani‐Gidlund K, Bjorck M. Open abdomen treatment after aortic aneurysm repair with vacuum‐assisted wound closure and mesh‐mediated fascial traction. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2013; 45: 588–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Björck M, Wanhainen A. Management of abdominal compartment syndrome and the open abdomen. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 47: 279–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Reintam A, Parm P, Kitus R, Kern H, Starkopf J. Primary and secondary intra‐abdominal hypertension – different impact on ICU outcome. Intensive Care Med 2008; 34: 1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Teubner A, Anderson ID, Scott NA, Carlson GL. Intra‐abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome (Br J Surg 2004; 91: 1102–1110). Br J Surg 2004; 91: 1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. De Waele JJ, De Laet I, Kirkpatrick AW, Hoste E. Intra‐abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis 2011; 57: 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kirkpatrick AW, Roberts DJ, De Waele J, Jaeschke R, Malbrain ML, De Keulenaer B et al Intra‐abdominal hypertension and the abdominal compartment syndrome: updated consensus definitions and clinical practice guidelines from the World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 1190–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheatham ML, Safcsak K. Percutaneous catheter decompression in the treatment of elevated intraabdominal pressure. Chest 2011; 140: 1428–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Waele JJ, Hoste EA, Malbrain ML. Decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome – a critical analysis. Crit Care 2006; 10: R51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dauplaise DJ, Barnett SJ, Frischer JS, Wong HR. Decompressive abdominal laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome in an unengrafted bone marrow recipient with septic shock. Crit Care Res Pract 2010; 2010: 102910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pearson EG, Rollins MD, Vogler SA, Mills MK, Lehman EL, Jacques E et al Decompressive laparotomy for abdominal compartment syndrome in children: before it is too late. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45: 1324–1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H et al The SOFA (Sepsis‐related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis‐Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 1996; 22: 707–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Malbrain ML, Cheatham ML, Kirkpatrick A, Sugrue M, Parr M, De Waele J et al Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra‐abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. I. Definitions. Intensive Care Med 2006; 32: 1722–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chiara O, Cimbanassi S, Boati S, Bassi G. Surgical management of abdominal compartment syndrome. Minerva Anestesiol 2011; 77: 457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Struck MF, Reske AW, Schmidt T, Hilbert P, Steen M, Wrigge H. Respiratory functions of burn patients undergoing decompressive laparotomy due to secondary abdominal compartment syndrome. Burns 2014; 40: 120–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Davis PJ, Eltawil KM, Abu‐Wasel B, Walsh MJ, Topp T, Molinari M. Effect of obesity and decompressive laparotomy on mortality in acute pancreatitis requiring intensive care unit admission. World J Surg 2013; 37: 318–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ghimenton F, Thomson SR, Muckart DJ, Burrows R. Abdominal content containment: practicalities and outcome. Br J Surg 2000; 87: 106–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Navsaria PH, Bunting M, Omoshoro‐Jones J, Nicol AJ, Kahn D. Temporary closure of open abdominal wounds by the modified sandwich‐vacuum pack technique. Br J Surg 2003; 90: 718–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rasilainen SK, Mentula PJ, Leppäniemi AK. Vacuum and mesh‐mediated fascial traction for primary closure of the open abdomen in critically ill surgical patients. Br J Surg 2012; 99: 1725–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Skoog P, Hörer TM, Nilsson KF, Norgren L, Larzon T, Jansson K. Abdominal hypertension and decompression: the effect on peritoneal metabolism in an experimental porcine study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2014; 47: 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ke L, Ni HB, Tong ZH, Li WQ, Li N, Li JS. The importance of timing of decompression in severe acute pancreatitis combined with abdominal compartment syndrome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013; 74: 1060–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]