Abstract

Background

Obstetrics remains the largest medico‐legal liability in healthcare. Neither an increasing awareness of patient safety nor a long tradition of reporting obstetric outcomes have reduced either rates of medical error or obstetric litigation. International debate continues about the best approaches to measuring and improving patient safety. In this study, we set out to assess the feasibility and utility of measuring the process of maternity care provision rather than care outcomes.

Aims

To report the development, application and results of a tool designed to measure the process of maternity care.

Materials and Methods

A dedicated audit tool was developed, informed by local, national and international standards guiding best practice and then applied to a convenience sample of individual healthcare records as proof of function. Omissions of care were rated in order of severity (low, medium or high) based on the likelihood of serious consequences on patient safety and outcome.

Results

The rate of high severity omissions of care was less that 2%. However, overall rates of all omissions varied from 0 to 99%, highlighting key areas for clinical practice improvement.

Conclusions

Measuring process of care provision, rather than pregnancy outcomes, is feasible and insightful, effectively identifying gaps in care provision and affording opportunities for targeted care improvement. This approach to improving patient safety, and potentially reducing litigation burden, promises to be a useful adjunct to the measurement of outcomes.

Keywords: clinical audit, clinical error, patient safety, pregnancy care

Introduction

Improved maternal and child health outcomes are key goals for those providing maternity care.1, 2 Measuring and reporting these outcomes have long been a cornerstone of high‐quality maternity care,3, 4, 5, 6 identifying opportunities for targeted improvements. This approach has underpinned regional and national review processes in Australia and elsewhere.3, 4, 5, 6

While reporting outcomes provides insightful compar‐isons between hospitals, regions or nations, it does not address why outcomes differ and how healthcare may be improved. Thus, measuring outcomes alone is unlikely to be ever able to provide a complete picture of the quality and safety of healthcare. Accordingly, it is increasingly apparent that measuring and reporting healthcare process will deliver better outcomes.7, 8

Access to antenatal care by trained professionals is fundamental to ensuring optimal maternal and child health outcomes.1, 2, 9, 10, 11 Recommended components of routine pregnancy care are well described and have been used to inform regulatory, professional and organisational expectations of care providers.1, 2, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 We used these recommendations, applying principles of patient safety and clinical audit methodology to measure pregnancy care, assessing whether such an approach would be feasible and informative.

Materials and Methods

We developed a clinical audit tool to measure pre‐defined elements of pregnancy care.18 Briefly, we used local, national and international clinical practice guide‐lines12, 13, 15, 16, 17 to develop minimum ‘standards’ of care against which provision of care was audited18 (Table 1). We divided the audit tool into five sections (demographic information, first pregnancy visit, antenatal screening, antenatal visits summary and documentation) and applied it to the health records of a random convenience sample of women who had given birth in an outer metropolitan maternity unit with about 1500 births per annum. Individual patient health records were hand searched, and data were entered and stored in a custom‐made database (Filemaker Pro 9.0 v3; Filemaker Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Data missing from a health record were recorded as absent or unavailable and the care assumed not to have been provided. Maternal or fetal conditions or clinical assessments that required further investigation or action and where no such action was recorded were interpreted as ‘abnormal not referred’.18 Such results were considered omissions of care with the potential to adversely affect patient safety, the latter being a higher severity omission. We acknowledge that missing information may not reflect deficiencies in care delivery but rather a deficiency in the recording of that care. However, in a healthcare system that depends upon multiple providers, a lack of documentation presents risks of harm. The number of women with omissions of care is reported as a percentage of the health records audited. The severity of the omission (low, medium, high) was determined by the degree to which care provision was within the control of the care provider, and/or its potential to cause harm. Specifically, a pragmatic approach to severity scoring was agreed between two of the authors (SS, EMW) depending on either the likelihood of the error to potentially cause significant harm or, in the case of omission of recording of care, the likelihood to expose the health service to successful litigation. Departures from care expectations as detailed in the hospital's own clinical practice guidelines17 were also accorded a higher severity rating because these were considered to reflect explicit local deficiencies. Data analyses were performed using Prism ® software (Prism 2008; GraphPad Software Inc., v5.0d, SanDiego, CA, USA).

Table 1.

Details of standards of care (* organisational documentation requirements are unreferenced)

| No. | Standard | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | If an early ultrasound (<14 weeks) result is available, the EDD is calculated from that ultrasound rather than the last known menstrual period (LMP). If an ultrasound is performed after 14 weeks gestation, the EDD is calculated from the last menstrual period (if known, monthly and regular) unless the ultrasound differs by more than one week. An ‘agreed’ EDD is to be made as early as possible in pregnancy and documented in the medical record and hand‐held card. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 2 | Women should have their visit pregnancy care visit, excluding a GP visit solely to confirm pregnancy, between 7 and 12 weeks’ gestation. | 21 |

| 3 | At the first visit, measure maternal weight and height and calculate body mass index (BMI) | 18, 19, 22 |

| 4a | A full medical and family history and a physical examination are to be completed at the first visit, and appropriate referral is made where indicated | 21 |

| 4b | At the first visit, discuss smoking behaviour/cessation, recreational drug use and alcohol consumption implications. At every subsequent visit, smoking behaviour enquiry and cessation advice and support is provided if indicated. | 22 |

| 5a | At the first pregnancy visit, women are to be offered the following investigations: blood group and antibodies, full blood examination (including screening for haemoglobinopathy); serology for syphilis, hepatitis B, HIV and rubella; midstream specimen of urine (for culture and sensitivity). | 18, 19, 21, 22 |

| 5b | All women should be offered Down Syndrome screening. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 6 | At the 2nd visit (12–15 weeks) all women should be offered a 19–21 week morphology ultrasound to assess gestational age, placental position and fetal morphology. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 7 | All women should be offered screening for diabetes during pregnancy. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 8a | An assessment of a woman's blood pressure must be made at every visit. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 8b | An assessment of symphyseo‐fundal height (SFH) should be measured at every visit after 20 weeks gestation. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 8c | Abdominal palpation to determine fetal lie and presentation should occur at every visit after 30 weeks gestation. | 18, 19, 22 |

| 8d | Women should be asked about fetal movements at every visit. | 22 |

| 8e | Neonatal vitamin K administration and Hepatitis B vaccination should be discussed during pregnancy. | 22 |

| 8f | Anti‐D administration to Rhesus (Rh) negative women | 22 |

| 9a | All pages in a health care record should have the patient's unique identifier. | * |

| 9b | All entries in a health care record should be legible, dated and signed, with each signature accompanied by the author's legible name. | * |

| 10 | Visit schedule: 10–12 weeks – hospital midwife assessment and confirmation of maternity booking, 12–15 weeks (obstetric review), 20–22 weeks (after mid‐trimester ultrasound performed), 26–28 weeks, 31 weeks, 34 weeks, 36 weeks, 38 weeks, 39 weeks (nullipara only), 40 weeks, 41 weeks. | 22 |

Ethics approval for the study was granted by Monash Health Human Research and Ethics Committee and by the Monash University Research Ethics Committee.

Results

A total of 354 health records, 24% of all women giving birth at the hospital, were analysed. To confirm validity, a random selection of 90 (25%) records was assessed independently. Inter‐rater reliability yielded a kappa score of 0.88.

Demographic data were collected for descriptive purposes. The 354 women were born in 52 different countries – 200 (55%) in Australia, 23 (6.5%) in India, 15 (4%) in New Zealand, 15 (4%) in Sri Lanka, 11 (3%) in Afghanistan and the remaining 81 in 46 other countries. Twenty (6%) women required an interpreter. The mean (range) age of the women was 28 (17–43) years.

Standards of care

Overall rates of compliance are detailed in Table 2. The rate of high severity errors was 1.7%.

Table 2.

Rate of non‐compliance with Standards of Care (** denotes HIGH risk item)

| Standard of care | Rate (%) non‐compliance | Standard of care | Rate (%) non‐compliance |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Visit (Standards 1–4) | |||

| EDD recorded | 0.3 | Physical examination recorded | 38.0 |

| EDD method recorded | 9.9 | Smoking status recorded | 3.1 |

| BMI recorded at first visit | 9.1 | Smoking follow‐up recorded | 11 |

| BMI>35 | 0.3 | Drug use status recorded | 1.4 |

| Medical history completed | 2.8 | Alcohol use follow‐up recorded | 2.3 |

| Family history completed | 2.5 | ||

| Screening (Standards 5–7) | |||

| Anti D to Rh neg woman recorded** | 5.6 | Positive MSU follow‐up recorded ** | 2.0 |

| FBE recorded | 2.5 | Offer of aneuploidy screening recorded | 41.8 |

| FBE follow‐up action recorded** | 0.3 | 11–14 week ultrasound result recorded | 1.7 |

| Syphilis result recorded | 5.4 | Abnormal 11–14 wk ultrasound follow‐up** | 0.3 |

| Hepatitis B result recorded | 1.7 | 11–14 week ultrasound not available | 26.8 |

| Positive Hep B follow‐up recorded ** | 1.1 | Fetal anatomy ultrasound recorded | 12.4 |

| Hep C recorded | 14.1 | Abn ultrasound follow‐up recorded ** | 1.1 |

| Rubella recorded | 2 | Fetal anatomy ultrasound not available | 29.1 |

| Non‐immune Rubella follow‐up recorded ** | 4.5 | Offer of gestational diabetes testing recorded | 14.4 |

| HIV screen recorded | 17.2 | Abnormal gestational diabetes follow‐up** | 0.3 |

| MSU recorded | 24.9 | Gestational diabetes result not available | 14.7 |

| Pregnancy Care (Standard 8) | |||

| BP measurement at each visit recorded | 11 | Abdominal palpation recorded at each visit | 4.0 |

| Abnormal BP follow‐up** | 1.1 | Abnormal abdominal palpation follow‐up** | 0.7 |

| Symphyseal‐fundal height result recorded at each visit | 7.9 | Fetal movements recorded at each visit | 7.6 |

| Appropriate follow‐up for abnormal SFH** | 1.1 | Neonatal drugs discussions | 40.1 |

| Documentation (Standards 9‐10) | |||

| Unique patient identifier completed | 1.7 | All entries have a signature | 50.3 |

| All entries dated | 2.3 | All signatures appear with a legible name | 98.9 |

| All entries are legible | 16.7 | ||

First pregnancy care visit

Standard 1: Calculation and recording of estimated due date (EDD)

Of the 354 records, one record (0.3%) did not have an EDD recorded. In 318 (90%) records, a first trimester ultrasound scan had been used to determine the EDD. Of the remaining 35 records, various methods have been used to calculate the EDD, only one of which was compliant with agreed organisational procedure. In total, 35 (10%) records were non‐compliant with standard 1. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 2: Gestation at first visit

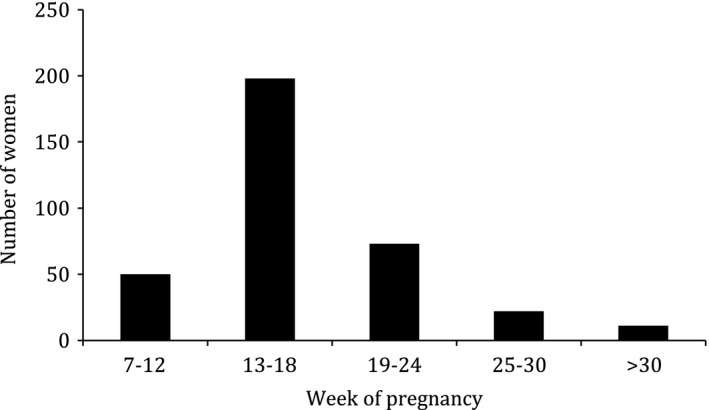

Fifty (14%) women had had their first antenatal visit by 12 weeks’ gestation (including those at 12 weeks gestation). The majority of women (198, 56%) were first seen at 13–18 weeks gestation (Fig. 1). Overall, the care for 304 (86%) women was outside the standard. Error severity: MODERATE.

Figure 1.

Gestation at first antenatal visit.

Standard 3: Calculation and recording of maternal body mass index (BMI) at first visit

Thirty‐two (9%) women did not have their BMI calculated at their first visit. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 4a: Medical and family history and physical examination

There were 224 (63%) records that were non‐compliant with this standard. Ten (3%) women had no record of a medical history being taken, and in nine (2%) women, there was no record of a family history being taken. There was no record of a physical examination in 133 women (38%). Error severity: MODERATE.

Standard 4b: Smoking, recreational drug use and alcohol consumption

Eleven (3%) women were not asked about smoking. Of the 45 women who reported that they smoked, 39 (87%) had no evidence of follow‐up questions during pregnancy. The health records of five women (1%) who indicated they had used recreational drugs showed no evidence of referral to support services. Seventeen (5%) women indicated alcohol use during pregnancy of >2 standard drinks per day, of whom only 11 (65%) were referred. Error severity: MODERATE.

Standard 5a: Early pregnancy investigations

One hundred and seventy‐four (49%) records were not compliant with this standard. In 9 women (2%), there was no evidence of a full blood examination (FBE). Twenty‐two health records indicated abnormal FBE results, one of which was not referred (4% of abnormal FBE results – HIGH severity). There was no evidence of syphilis screening in 19 women (5%) (MODERATE severity). Hepatitis B screening was not evident in 6 records (2%), (MODERATE severity). Of 8 women with positive hepatitis B serology, 4 (50%) were not referred (HIGH severity). Assessment of Rubella immunity was not evident in seven health records (2%) (LOW severity). In the 56 women with no Rubella immunity, there was no evidence of follow‐up in 16 (29%) (LOW severity). In 61 health records, there was no evidence of HIV screening (17%) (HIGH severity). In 88 health records (25%), there was no evidence of a midstream urinalysis (MSU) (LOW severity). Of the 17 positive MSU results, seven were not acted upon (41%) (HIGH severity).

Standard 5b: Aneuploidy screening

In 148 (42%) health records, there was no evidence of either the offer or performance of Down syndrome screening. Error severity: HIGH.

Standard 6: Midpregnancy ultrasound

There was no evidence that a midpregnancy (18–22 weeks) ultrasound scan had been performed in 44 (12%) women. Twenty‐nine women had a fetal abnormality recorded, of which 4 (14%) were not referred appropriately. Error severity: HIGH.

Standard 7: Screening for gestational diabetes

Evi‐dence of the offer of testing for gestational diabetes (GDM) was absent in the records of 51 (14%) women. The result of GDM testing was abnormal in 61 women, of whom one was not acted upon (2%). The results of GDM testing were not available for 52 (17%) women. Error severity: MODERATE.

Pregnancy care

Standard 8a: Measurement of blood pressure

Blood pressure (BP) measurement was not recorded at every visit in the health records of 39 (11%) women (MODERATE severity). New onset hypertension was recorded in the records of 21 women, of whom 4 (19%) were not acted upon (HIGH severity).

Standard 8b: Assessment of fetal growth

Symphyseal‐fundal height (SFH) was not measured at every visit after 20 weeks in 28 (8%) women. Twenty assessments of SFH were recorded as abnormal, of which four (20%) were not acted upon. Error severity: MODERATE.

Standard 8c: Abdominal palpation

Abdominal palpa‐tion at every visit after 30 weeks was not evident in the health records of 14 (4%) women. There were 20 abnormal abdominal palpation results recorded, with two (10%) not acted upon. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 8d: Fetal movements

For 27 (8%) women, there was no evidence that she was asked about fetal movements. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 8e: Neonatal vitamin K administration and Hepatitis B vaccination

This was not evident in 144 (40%) health records. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 8f: Rhesus prophylaxis program

Thirty‐six women were Rh negative. In 2 (6%) of these women, there was no record of anti‐D being administered. Error severity: HIGH.

Documentation

Standard 9a: Use of patient's unique identifier

Six (1.7%) health records did not have a unique patient identifier on every page. Error severity: LOW.

Standard 9b: Signing of medical record entries

In eight (2%) health records, there were entries that were not dated. There were missing signatures in the records of 178 women (50%) and missing legible name in those of 350 (99%). In 59 health records (17%), not all entries in the record were legible. Error severity: MODERATE.

Standard 10: Schedule of visits

There was poor compliance with the recommended schedule of visits, particularly in the third trimester when a large number of healthy women with a normal pregnancy had an apparently excessive number of visits.

Discussion

In this study, we have assessed the feasibility of using a bespoke clinical audit tool to assess pregnancy care, as defined by compliance with hospital policies, as an adjuvant approach to improving safety and quality of healthcare. We found that deficiencies in care were evident in 85% of case‐records but that deficiencies that could have significantly compromised pregnancy outcomes were evident in less than 2%. We believe that this approach could be readily embedded in maternity services to be used with established measurement of perinatal outcomes to guide improvements.

While patient safety is paramount in health care delivery, there remains little agreement on how best to measure it.7, 8, 9, 10, 19, 20 Many diverse approaches and tools have been reported.21, 22, 23 However, we were unable to identify any that assessed the continuum of pregnancy care. Accordingly, we developed the tool to audit care against a number of standards.18 That the rate of a ‘high severity’ avoidable errors was less than 2% suggests that overall care was of a reasonable standard. However, a reasonable or acceptable error rate was not agreed upon prior to the study and there is not broad agreement on this in the literature. Reported medical error rates range from 2 to 40%, depending on associated patient risk factors and co‐morbidities.8, 20, 24, 25 Reports about patient safety in an ambulatory setting have been published,26, 27, 28, 29 although none relate to maternity care, and analyses have been limited to only those records where adverse events were known to have occurred. Thus, as far as we are aware, this is the first attempt to measure the rate of care process compliance as an outcome in itself.

Having established a baseline error rate (85%) and a critical error rate (2%) for our service, we believe that the next step is to determine acceptable error rates. We would suggest that the acceptable error rate will differ for severe errors – likely to be a zero – and minor‐to‐moderate errors. We are now engaged with the service to set these rates.

The high rates of unavailable data (up to 85%) from the health records should be a major concern for both individual clinicians and the organisation. Documentation of care is fundamental to the transfer of clinical information between care providers, particularly when large components of care, such as in pregnancy, may be provided in the community by non‐hospital staff. In these instances, access to hospital information technology systems can be inconsistent or non‐existent. Effective reporting relies on transcription from files retained by the medical practitioner to a woman's handheld record, which ultimately is filed in the health record. There is also the issue of woman's choice of pathology provider and medical provider preference of pathology services. In cases where there is no interface between the pathology provider and hospital information systems, data collection again relies on manual transcription. This study identified compelling system failures that are likely to be replicated in other maternity services but that could be readily overcome with integrated information management systems such as afforded by an electronic medical record. Indeed, an electronic medical record that was configured to prompt the user to complete the summary of care provision, in effect to manage care, would be expected to dramatically improve compliance, to improve the flow of information between clinicians and to improve quality of care. One outcome from this study is to highlight for the health service the potential value of an integrated electronic maternity record.

In addition to highlighting critical areas of risk exposure, the audit tool identified opportunities to improve organisational systems of care and deliver efficiencies. For example, the majority of women received their first antenatal visit after 13 weeks gestation, principally due to lack of sufficient appointments. However, fifty women who were assessed as being at low risk of developing complications were over‐serviced by having too many antenatal visits. For example, one woman was seen 16 times after 28 weeks of pregnancy without any apparent reason or pregnancy complication. These insights provided opportunities for the health service to improve scheduling and thereby free up appointment times for better use in early pregnancy. These changes would be expected to save costs and improve care. Our tool provides a means to assess whether improvements and compliance are then achieved.

Our interpretation that omissions in the health record reflect omissions of care may be perceived as extreme. We acknowledge that omissions in documentation do not prove that care was not provided. However, it is difficult to argue that care was offered or provided if there is no documented evidence for it. For example, in the case of aneuploidy screening, it would be difficult to defend care where a woman gives birth to a child with Down syndrome and claims wrongful birth stating that she was never offered testing and would have terminated the pregnancy had she known, if there was no record that counselling had taken place. Similarly, the lack of evidence of HIV screening or of appropriate referral for abnormal hepatitis serology or an abnormal fetal anatomy ultrasound are of great concern. Highlighting these deficiencies enabled changes to results management to improve patient care.

Limitations

The key limitation in our work is that to date, this exercise has been necessarily limited to measuring process. Whether measurement and reporting of the results will lead to change and ultimately to improved process and better outcomes has yet to be demonstrated. Ideally, such future ‘intervention’ studies should be designed and report findings in accord with the standards for quality improvement reporting excellence (SQUIRE) guidelines.30 Further, the study was undertaken within a single hospital and the results may not be generalisable beyond the site under review. In particular, the grading of error severity is likely to vary depending on an individual hospital guidelines. For example, if routine screening for gestational diabetes is not required in a given hospital, then the lack of provision of such screening would not be recorded as an error as it would be in our service. The development of regional or national guidelines and standards, such as those published by NHMRC12 or NICE,13, 14 would assist in the development of uniform error severity scoring.

Conclusions

We believe that this study usefully contributes to the knowledge of measuring safety in pregnancy care by providing a broad assessment of the entirety of antenatal care, identifying important opportunities for care improvement. Most importantly, we have shown that it is both feasible and insightful to measure process of care in addition to outcomes of care as an adjuvant approach to improving quality and safety.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the support and engagement of Health Service where the research was based and the Victorian Government's Department of Health and Operational Infrastructure Support Program for financial support.

References

- 1. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . Safer Childbirth: MINIMUM Standards for the Organization and Delivery of Care in Labour. London, UK: RCOG Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Commonwealth Government of Australia . Improving Maternity Services in Australia. The report of the maternity services review. Commonwealth of Australia, Barton ACT 2009. (Publications No. P3‐4946).

- 3. Knight M, Kenyon S, Brocklehurst P. et al (eds) on behalf of MBRRACE‐UK . Saving Lives, Improving Mother's Care – Lessons learned to inform future maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009‐12. Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Z, Zeki R, Hilder L, Sullivan E. Australia's mothers and babies 2011. Perinatal Statistic Series Number 28. Cat. No. PER 59. Canberra: AIHW National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit.

- 5. Consultative Council on Obstetric and Paediatric Mortality and Morbidity . 2010/2011 Victoria's Mothers and Babies. Victoria's Maternal, Perinatal, Child and Adolescent Mortality. CCOPMM, Melbourne 2014.

- 6. Department of Health and Human Services . Victorian Perinatal Services Performance Indicators 2012–13. Melbourne: Victorian Government, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pronovost P, Goeschel C. Viewing health care delivery as science: challenges, benefits, and policy implications. Health Serv Res 2010; 45: 1508–1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Pronovost PJ, Colantuoni E. Measuring preventable harm: helping science keep pace with policy. JAMA 2009; 301: 1273–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Petrou S, Kupek E, Vause S, Maresh M. Antenatal visits and adverse perinatal outcomes: results from a British population‐based study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2003; 106: 40–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barros A, Ronsmans C, Axelson H et al Equity in maternal, newborn and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 2012; 379: 1225–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldenberg R, McClure E. Disparities in interventions for child and maternal mortality. Lancet 2012; 379: 1178–1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council . Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing, Canberra 2012. Available from http://www.health.gov.au/antenatal (accessed 20/8/15).

- 13. National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health . Antenatal Care: Routine Care for Healthy Pregnant Women. London, UK: RCOG Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Antenatal Care. NICE quality standard 22. Guidance.nice.org.uk/qs22 (accessed 17/11/15). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nursing and Midwifery Board of Australia . National competency standards for the midwife. Available from: http://www.nursingmidwiferyboard.gov.au/Codes-Guidelines-Statements/Professional-standards.aspx (accessed 20/8/15).

- 16. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . College Statements: Obstetrics. Available from: http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/college-statements-guidelines.html#obstetrics (Accessed 20/8/15).

- 17. Monash Health . Pregnancy tests, investigations and key visit information. Clinical Guideline. Available from http://system.prompt.org.au/download/document.aspx?id=3205821&code=34D92259041C9CB2E5A483A97E9BB586 (Accessed 20/8/15).

- 18. Sinni S, Cross W, Wallace E. Designing a clinical audit tool to measure processes of pregnancy care. Nurs Res and Rev 2011; 1: 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sinni S, Wallace E, Cross W. Patient safety: a literature review to inform an evaluation of a maternity service. Midwifery 2011; 27: 274–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Brennan T, Leape L, Laird N et al Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. Qual Saf Health Care 2004; 13: 145–151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Victorian Department of Health . Clinical Risk Management. Available from http://health.vic.gov.au/clinrisk/ (Accessed 20/8/15).

- 22. Institute for Healthcare Improvement . Tools. Available from http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/default.aspx (Accessed 20/8/15).

- 23. Graham WJ. Criterion‐based clinical audit in obstetrics, bridging the quality gap? Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009; 23: 375–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Weingart S, Wilson R, Gibberd R, Harrison B. Epidemiology of medical error. BMJ 2000; 320: 774–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Vries E, Ramrattan M, Smorenburg S et al The incidence and nature of in‐hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17: 216–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hammons T, Piland N, Small S et al Ambulatory patient safety what we know and need to know. J Ambul Care Manage 2003; 26: 63–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gandhi T, Seger A, Overhage J et al Outpatient adverse drug events identified by screening electronic health records. J Patient Saf 2010; 6: 91–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schnall R, Bakken S. Reporting of hazards and near‐misses in the ambulatory care setting. J Nurs Care Qual 2011; 26: 328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Poon E, Gandhi T, Sequist T et al “I wish I had seen this test result earlier!”: dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Int Med 2004; 164: 2223–2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ogrinc G, Mooney SE, Estrada C et al The SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence) guidelines for quality improvement: explanation and elaboration. Qual Saf Health Care 2008; 17(Suppl 1): i13–i32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]