Abstract

Vortices are topological defects accounting for many important effects in superconductivity, superfluidity, and magnetism. Here we address the stability of a small number of such excitations driven by strong external forces. We focus on Abrikosov-Josephson vortex that appears in lateral superconducting S/S’/S weak links with suppressed superconductivity in S’. In such a system the vortex is nucleated and confined in the narrow S’ region by means of a small magnetic field and moves under the effect of a force proportional to an applied electrical current with a velocity proportional to the measured voltage. Our numerical simulations show that when a slow moving Abrikosov-Josephson vortex is driven by a strong constant current it becomes unstable with respect to a faster moving excitation: the Josephon-like vortex. Such a current-driven transition explains the structured dissipative branches that we observe in the voltage-current curve of the weak link. When vortex matter is strongly confined phenomena as magnetoresistance oscillations and reentrance of superconductivity can possibly occur. We experimentally observe these phenomena in our weak links.

In the last decade superconductivity at reduced dimensionality has received a growing interest mainly due to the huge advancements in nano-fabrication techniques that have permitted exploration and discovery of new physical phenomena when approaching the mesoscopic limit. Thin films of type II superconductors are in the mesoscopic limit when their thickness is much smaller than the London penetration depth λ1, and have at least a lateral dimension intermediate between the Ginzburg-Landau coherence length ξ and the Pearl length Λ1. Effects due to strong confinement of vortex matter2 in mesoscopic superconducting films, such as critical current and magnetoresistance oscillations3,4,5, counterintuitive reentrance of superconductivity caused by magnetic field6,7 or realization of a Weber blockade in a superconducting material8, have been recently demonstrated. The mechanism of phase slippage1,9,10 and related concept of kinematic vortex11,12, previously introduced to account for transport properties of micro-bridges and whiskers, has gained a renewed interest also in the explanation of transport properties of plain thin superconducting films at mesoscale13,14,15,16,17,18 (with or without holes) and nanowires19,20,21,22,23. The same mechanism could play an important role in the dynamics of iron-based superconducting grain boundary junctions, where the presence of weak links has been identified through noise spectroscopy24. Moreover, nano-fabrication techniques also permitted to revisit the physics of proximity effect25 between a superconducting material and a non superconducting material and related Josephson effects26 in lateral weak links27 at mesoscale. Using this kind of weak links, triplet superconductivity28 induced in a ferromagnetic half metal29, weak superconductivity induced in graphene30, evidence for nonlocal electrodynamics in Josephson junctions and related concept of Abrikosov-Josephson vortex31,32,33,34, and direct observation35 of Josephson vortex cores have been reported.

Very recently, exploiting the phenomenon of noticeable reduction36,37 of superconductivity at interface between a ferromagnet and a superconducting material, mesoscopic lateral S/S’/S weak links in which the weak S’ region is made of same material as the S banks, though with reduced critical temperature, have been reported. In such kind of structure Josephson coupling38,39,40, also controllable by current injection40 from the ferromagnetic layer, has been demonstrated at temperatures near the critical temperature of banks while at lower temperatures a more complex behaviour has been found. In the present report we further address such type of lateral S/S’/S weak link, both experimentally and numerically, with particular emphasis on transport properties and vortex dynamics in the presence of magnetic field. The S’ region is achieved crossing a thin, narrow and long ferromagnetic Permalloy strip directly on the top of a thin superconducting Niobium strip in the mesoscopic regime. In the absence of magnetic field, the weak link exhibits a single phase slip line branch with appreciably large current range extension. In the presence of magnetic field, the recently predicted41 magnetoresistance oscillations accounted for strongly confined vortex matter in a weak superconductivity region are experimentally confirmed. Moreover, the S/S’/S weak link exhibits voltage-current curves with structured dissipative branches. The numerical analysis, performed in the framework of time dependent Ginzburg-Landau model for mesoscopic type II superconductors with inhomogeneous critical temperature, suggests that these peculiar branches are accounted for a dynamical transition from a single row of slow moving moderately anisotropic vortices (Abrikosov-Josephson vortices31,32,33) to a single row of faster moving definitely anisotropic vortices (Josephson-like vortices). The first experimental evidence for voltage-current curves accounted for such a current driven transition in a planar weak link, and the observation of magneto-resistance oscillations recently predicted41 for such type of weak links are the main results of the present report.

Results

The samples were fabricated using Niobium (Nb) as superconductor and Permalloy (Py: Ni80Fe20) as ferromagnet as described in Methods. A micrograph of final sample layout is shown in the inset of Fig. 1(a). The weak links (labeled as SF in the micrograph) are formed where the horizontal Py stripes crosses the vertical Nb strip. In this crossing region we are concerned with a Superconductor-Ferromagnet bilayer (SF) and, due to proximity effect25,36,37, the Nb below Py is an S’ region with superconductivity weakened with respect to the superconductivity of the uncovered S region, so that a lateral S/S’/S weak link is realized.

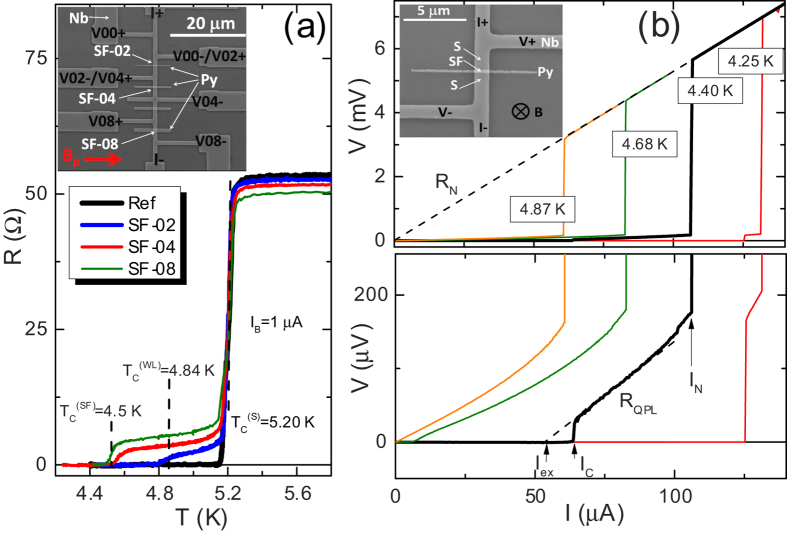

Figure 1. Electrical characterization of samples at zero applied magnetic field.

(a) R(T) curves of the reference Nb strip (black line) and the Nb/NbPy/Nb lateral weak links with width of the Py strip of 0.2 μm (blue line), 0.4 μm (red line), and 0.8 μm (green line). In the inset there is shown a micrograph of the sample layout. (b) V(I) curves of the weak link with 0.2 μm wide Py strip recorded at several temperatures in the absence of magnetic field are shown in the top panel in full voltage range. The inset shows the micrograph of the addressed weak link. The low voltage region of the V(I) curves is shown amplified in the bottom panel.

In the main panel of Fig. 1(a) there are shown the R(T) (resistance versus temperature) curves of the weak links with lengths 0.2 μm, 0.4 μm, and 0.8 μm, together with the R(T) curve of reference strip. The R(T) of the 0.6 μm wide weak link (not shown here to not make further heavy the plot) was found to consistently fall between the R(T) curves of the 0.4 μm and the 0.8 μm wide weak links. To acquire the R(T), a dc bias current IB = 1 μA was used, but similar results were obtained using an ac current bias or a lower dc current bias. The critical temperature of all the S banks is found to be about  , the same as the reference strip, while the critical temperature of the weak region (SF bilayer) decreases as the length of the weak link is increased and tends to saturate at the longest weak link. This is due to lateral superconducting proximity effect, i.e., the one induced by banks, that becomes negligible when separation between banks is much larger than superconducting coherence length. Assuming the lateral proximity effect as negligible already for the 0.8 μm long weak link, we estimate the proximity-effect-free critical temperature (common to all weak links) of our Nb(30 nm)/Py(30 nm) bilayer as approximately

, the same as the reference strip, while the critical temperature of the weak region (SF bilayer) decreases as the length of the weak link is increased and tends to saturate at the longest weak link. This is due to lateral superconducting proximity effect, i.e., the one induced by banks, that becomes negligible when separation between banks is much larger than superconducting coherence length. Assuming the lateral proximity effect as negligible already for the 0.8 μm long weak link, we estimate the proximity-effect-free critical temperature (common to all weak links) of our Nb(30 nm)/Py(30 nm) bilayer as approximately  . In the following we will concentrate on the 0.2 μm long weak link, where, instead, a relevant lateral proximity effect can be inferred to exist for a quite large temperature window. From the R(T) curve shown in Fig. 1(a) we estimate a critical temperature

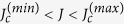

. In the following we will concentrate on the 0.2 μm long weak link, where, instead, a relevant lateral proximity effect can be inferred to exist for a quite large temperature window. From the R(T) curve shown in Fig. 1(a) we estimate a critical temperature  for this laterally proximized weak link. Thus, we can conclude that it represents a S/S’/S weak link in the temperature window

for this laterally proximized weak link. Thus, we can conclude that it represents a S/S’/S weak link in the temperature window  , a proximized S/N/S (existence of a measurable critical current) in the temperature range

, a proximized S/N/S (existence of a measurable critical current) in the temperature range  , and an ordinary S/N/S structure (unmeasurably small critical current) for

, and an ordinary S/N/S structure (unmeasurably small critical current) for  .

.

We notice that in Fig. 1(a) the fully normal state resistance a  is not exactly the same for all samples. As explained in Methods, this is it not due to a non uniform Nb or lithography errors, but rather to the presence of a Nb/Py bilayer with variable length between the voltage probes at fixed distance.

is not exactly the same for all samples. As explained in Methods, this is it not due to a non uniform Nb or lithography errors, but rather to the presence of a Nb/Py bilayer with variable length between the voltage probes at fixed distance.

A zoomed micrograph of the further addressed weak link is shown in the inset of Fig. 1(b). In the top panel we show the V(I) curves at full scale of voltage recorded at several temperatures and in the absence of magnetic field. The curves are always acquired increasing the current from zero to a suitably large target value, without making a full current loop. This is because in this work we were not interested in hysteresis effects. However, the hysteresis was always found to be negligible. As can be appreciated, beyond an upper temperature-dependent critical current IN all curves fall on the same fully resistive branch passing trough the origin with slope  , comparable to the resistance of the Nb strip in the fully normal state (but for the correction discussed in Methods). We ascribe such a branch to the transition of Nb banks to the fully normal state. For currents below IN the V(I) curves are more structured, as it better evident in the bottom panel of Fig. 1(b), where the low voltage region is amplified. By increasing current from zero, a zero voltage state is observed up a temperature-dependent critical current Ic, defined as the current at which a transition V = 0 → V ≠ 0 take place using a 0.2 μV criterion, above which an intermediate dissipative branch is followed up to IN, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Approximately the dynamical resistance RQPL of this branch is comparable to the temperature-dependent resistance of the weak link region in the normal state, 2 Ω < RQPL < 3 Ω, as can be appreciated from the R(T) curve reported in Fig. 1(a). Though these branches are almost linear for currents not too large with respect to Ic their extrapolation to the zero voltage axis points to a finite current “excess” current27

Iex, strictly reminding the branches observed1 in other types of weak links or in mesoscopic strips at very large driving currents and accounted for phase slip lines/kinematic vortices11,12. As will be discussed below also in our case these branches can be accounted for phase slip lines. Compared to other cases, here we observe only a single phase slip branch, due to the short length of the weak region (0.2 μm). For what said above about the different regimes, the curves V(I) recorded at 4.25 K, and 4.40 K are for the weak link in the S/S’/S regime, the curve at 4.68 K is for the laterally proximized S/N/S regime, while the curve at 4.87 K belongs to the pure S/N/S regime. Below we further address the weak link at T = 4.25 K, i.e., the S/S’/S regime.

, comparable to the resistance of the Nb strip in the fully normal state (but for the correction discussed in Methods). We ascribe such a branch to the transition of Nb banks to the fully normal state. For currents below IN the V(I) curves are more structured, as it better evident in the bottom panel of Fig. 1(b), where the low voltage region is amplified. By increasing current from zero, a zero voltage state is observed up a temperature-dependent critical current Ic, defined as the current at which a transition V = 0 → V ≠ 0 take place using a 0.2 μV criterion, above which an intermediate dissipative branch is followed up to IN, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Approximately the dynamical resistance RQPL of this branch is comparable to the temperature-dependent resistance of the weak link region in the normal state, 2 Ω < RQPL < 3 Ω, as can be appreciated from the R(T) curve reported in Fig. 1(a). Though these branches are almost linear for currents not too large with respect to Ic their extrapolation to the zero voltage axis points to a finite current “excess” current27

Iex, strictly reminding the branches observed1 in other types of weak links or in mesoscopic strips at very large driving currents and accounted for phase slip lines/kinematic vortices11,12. As will be discussed below also in our case these branches can be accounted for phase slip lines. Compared to other cases, here we observe only a single phase slip branch, due to the short length of the weak region (0.2 μm). For what said above about the different regimes, the curves V(I) recorded at 4.25 K, and 4.40 K are for the weak link in the S/S’/S regime, the curve at 4.68 K is for the laterally proximized S/N/S regime, while the curve at 4.87 K belongs to the pure S/N/S regime. Below we further address the weak link at T = 4.25 K, i.e., the S/S’/S regime.

Transition from Abrikosov-Josephson to Josephson-like vortex motion, and magnetoresistance oscillations

In S/S’/S weak links with the length of S’ region suitably small (not too large with respect to coherence length at working temperature) a modulation of the critical current as a function of magnetic field could be expected, due to the presence of a small number of strongly confined vortices4,5,41,42 or, more simply, to the presence of a Josephson coupling26. In our sample we observe critical current oscillations. The modulation of critical current as a function of magnetic field, Ic(B), recorded at T = 4.25 K, is shown in Fig. 2(a). The magnetic field is applied perpendicular to the substrate, as shown in the top inset of Fig. 1(b). We also show the Ic(B) of the reference sample (solid line) for comparison. As can be appreciated, for the very small range of magnetic fields involved the critical current of the reference sample barely decreases of some percents, so we are confident that vortices in the banks are again not present43 for these fields and the oscillations are due only to the weak region.

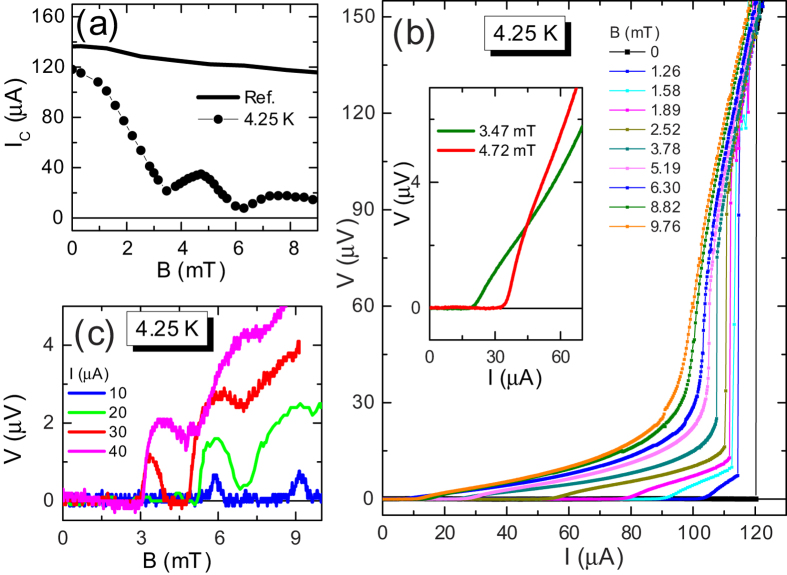

Figure 2. Evidence for magnetoresistance oscillations and Josephson-like vortex in action.

(a) Modulation of critical current as a function of magnetic field, Ic(B), recorded at T = 4.25 K (solid circles). The Ic(B) of the reference sample (solid line) is also shown for comparison. (b) V(I) curves recorded for several values of applied magnetic field. The inset shows a magnification of the curves recorded at magnetic fields corresponding to the first minimum and first relative maximum of the Ic(B) pattern shown in panel (a). (c) Voltage versus magnetic field, V(B), curves recorded for several values of fixed bias current I.

For this temperature the periodicity of oscillations is not well defined, and the pattern reminds the one reported40 in a lateral weak link very similar to the one addressed here. More generally the pattern reminds more the one exhibited by Josephson tunnel junctions of intermediate width26 with overlap geometry26 than the one (Fraunhofer-like) exhibited by junctions of short width26. As explained in Methods, and confirmed in the numerical simulations, in fact this is the case for our weak link.

In Fig. 2(b) we show the V(I) curves in the low voltage region for values of applied magnetic field ranging from B = 0 to B = 9.76 mT. We checked that no asymmetry or magnetic field-induced hysteresis44,45,46,47,48 was present in the V(I) curves when magnetic field direction was reversed or a full magnetic loop was performed. This reassures us that the field sensed by the weak link is really homogeneous, the Py rests in a single domain state, and the thickness profile of thin Nb film is flat. At very low fields, above the field-dependent critical current Ic(B), an almost linear dissipative branch with low dynamical resistance is followed. Then, after a very small non linear branch, an abrupt transition to the phase slip line branch is achieved at some critical current. By increasing the magnetic field the current range of the low resistivity branch extends, and, above a certain magnetic field value, continuously merges in the phase slip line branch. The continuous transition region exhibits a dynamical resistance larger than the RQPL.

The low resistivity portion of curves reminds the flux flow branches reported49 in mesoscopic superconducting strips subjected to a perpendicular magnetic field or the branches predicted for weak links with very high critical current density31,32,33. However, here also a transition, abrupt at low field and continuous at moderate fields, to a phase slip line branch is observed. As will be better clear in the next section, features of V(I) curves reported in Fig. 2(b) can be explained with presence of Abrikosov-Josephson31,32,33 vortex flow at low current that transforms in Josephson-like vortex flow at larger currents.

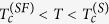

Inspection of very low voltage region suggests that to the modulation of critical current corresponds also a modulation of the dynamical resistance of the linear flux flow regime. This can be better appreciated in the inset of Fig. 2(b), where we show a magnification of the curves recorded at magnetic fields corresponding to the first minimum and first relative maximum of the Ic(B) pattern at T = 4.25 K shown in Fig. 2(a). The resistivity of the flux flow branch at first minimum (green line) is lower than the resistivity of the branch at first maximum (red line) suggesting that mobility of vortices can be tuned41 by magnetic field and can possibly exhibit oscillations. In particular, as we could infer looking at the curves in the inset, if the bias current is fixed between the value of critical current at first minimum  and the value of critical current at first maximum

and the value of critical current at first maximum  , vortices in motion (meaning V ≠ 0) at lower field can be stopped at larger field (meaning V = 0), i.e., it is possible a reentrance of superconducting state when magnetic field is increased. The magneto-resistance oscillations observed in our sample are shown in Fig. 2(c), where we report voltage versus magnetic field, V(B), curves for several values of fixed bias current I. In particular the red curve exhibiting a reentrance of superconductivity corresponds to

, vortices in motion (meaning V ≠ 0) at lower field can be stopped at larger field (meaning V = 0), i.e., it is possible a reentrance of superconducting state when magnetic field is increased. The magneto-resistance oscillations observed in our sample are shown in Fig. 2(c), where we report voltage versus magnetic field, V(B), curves for several values of fixed bias current I. In particular the red curve exhibiting a reentrance of superconductivity corresponds to  .

.

Discussion

In order to investigate the response of the weak link to driving current and magnetic fields, we use the time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau (TDGL) theory where the presence of weak region is included through a spatially dependent critical temperature Tc. This approach, already used in the past11,27,41 to describe superconducting weak links, is based on the anisotropic Ginzburg-Landau formalism, where the weak link is described by an anisotropic expansion coefficient1,25 α(T) of the Gibbs free energy density. We use the model in its 2D simplified form. The simplification is justified when the strip exhibits a large Ginzburg-Landau parameter κ (definitely type-II superconductor) and it is in the mesoscopic limit4,43, i.e., it is very thin with respect to the London penetration depth (tff ≪ λ), sufficiently narrow with respect to the Pearl length (W ≤ Λ = 2λ2/d), and quite wider than the Ginzburg-Landau coherence length (Wf ≫ ξ). In the mesoscopic limit current density is uniform with good approximation43,50 (at least in regions far from sharp turns or geometrical non-uniformities43,50,51,52, as it is our case) and internal magnetic field corrections due to current as well as the demagnetizing effects can be usually neglected4,43,50.

The 2D TDGL equation for the complex order parameter ψ = |ψ|eiθ in the case of our inhomogeneous superconducting strip [see inset of Fig. 3(a)] takes the form11,27,41

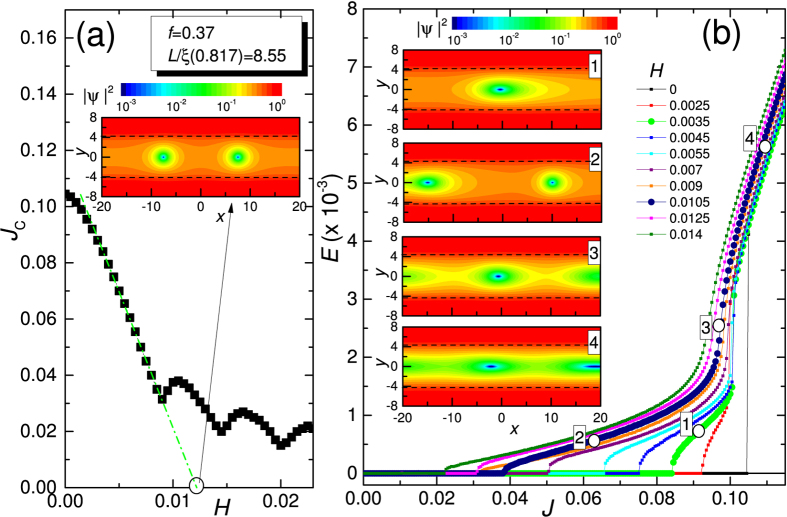

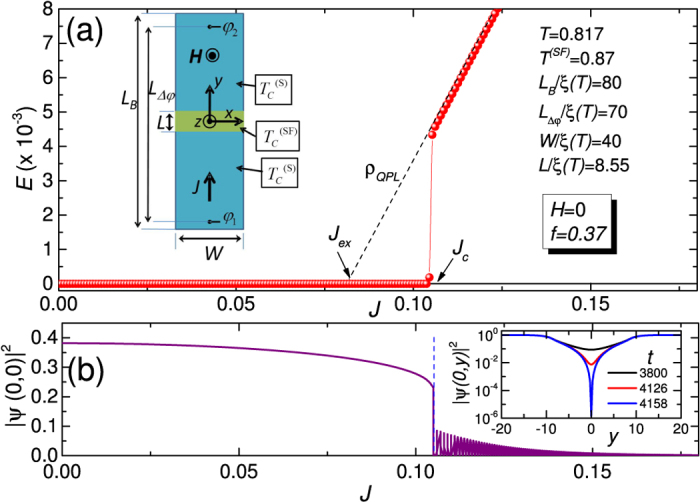

Figure 3. Calculated E(J) curve at H = 0: phase slip line branch.

(a) Calculated time averaged electric field versus applied current density, E(J), of the weak link at zero applied magnetic field. In the inset there is shown the geometry used to model the real S/SF/S lateral weak link structure. The used reference frame and parameters of the simulations are also shown. (b) Squared order parameter at the center of weak link versus applied current density at zero applied magnetic field. Above the critical current density Jc the order parameter is oscillating with time. In the inset there is shown the profile of the squared order parameter along y-direction [see inset of panel (a)] at several times when the weak link is polarized on the dissipative branch.

|

where A is the vector potential associated to the external magnetic field H, ϕ the electrostatic potential, u = 5.79 governs the relaxation of the order parameter10, and f is the anisotropy parameter discussed below. This equation is coupled with the equation for the electrostatic potential

|

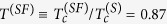

that stems from the current conservation equation J = Js + Jn = [Im(ψ*(∇ − iA)ψ)] − ∇ϕ. All physical quantities are measured with respect the temperature dependent critical values of the banks, as explained in Methods. The field H is applied in the z-direction and is described by A = (−Hy/2, Hx/2, 0). In this implicit-temperature formulation the anisotropy parameter11,27,41 becomes f(y) = 1 in the banks and f(y, T) = (T(SF) − T)/(1 − T) in the weak link, where  . Further details on numerical integration of equations (1), and (2) are given in the Methods.

. Further details on numerical integration of equations (1), and (2) are given in the Methods.

Before we proceed, we would briefly comment that the simplified 2D model (1), and (2) should be sufficient to describe the experiment. For the used dimensions, the as grown Py stripes are expected to be all in the remanent single-domain magnetic state, due to small thickness, large length-to-width aspect ratio, and sub-micrometer scale widths. However, prior the measurements we applied a magnetic field BP ≈ 200 mT in the long direction of the stripes [see micrograph in Fig. 1(a)] at room temperature. This ensures that remanent single-domain magnetization is directed along the length of the strips. Moreover, in magneto-transport measurements we applied a magnetic field perpendicular to the Py strip plane up to 10 mT. We checked, using the 3D simulation package Object Oriented Micromagnetic Framework (OOMMF), that this field strength is too small to rotate the magnetization to the out-of-plane direction and that, more generally, the out-of-plane stray magnetic field component in the weak link regions (i.e., around the middle of the strip) can be neglected with respect to the applied magnetic field. This allows us to exclude any other mechanism44,45,53,54 of modulation of superconductivity beside the proximity effect at Superconductor/Ferromagnet interface. Proximity effect1,25 between a superconducting (S) material and a non superconducting material (N) manifests itself as gain of weak superconductivity in the N at expense of reduction of superconductivity in the S near the S/N interface. The reduction of superconductivity in S can be quite strong36,37 when the N material is also ferromagnetic (F). This is why we preferred to use a ferromagnetic metal to locally depress superconductivity in Nb instead of an ordinary normal metal. In our system the reduction of superconductivity in the Nb is achieved in the vertical direction of the structure [z-direction in the model shown in Fig. 3(a)] and accounts for the reduced critical temperature of Nb below the Py stripes. The reduction extends for a distance of the order of the coherence length ξ(T) from the S/F interface36,37, so that Nb below Py could exhibits a modulation of superconductivity along the vertical direction in our system and a full 3D model should be used. To avoid this, a thickness tf lower than approximately √2 ξ(T)1,25 for the superconductor should be chosen. This is why we chose a 30 nm-thick Nb. In fact, we estimate for our Nb (see Methods)  , resulting in tf ≤ √2 ξ(T) in the temperature range of our interest (T ≥ 0.8). So, we can reasonably assume the superconductivity in the Nb as homogeneously depressed in the vertical direction, as also suggested by resistance measurements and magnetic pattern analysis given in Methods, and we use the simplified 2D formulation given above.

, resulting in tf ≤ √2 ξ(T) in the temperature range of our interest (T ≥ 0.8). So, we can reasonably assume the superconductivity in the Nb as homogeneously depressed in the vertical direction, as also suggested by resistance measurements and magnetic pattern analysis given in Methods, and we use the simplified 2D formulation given above.

As in the experiments, we focused simulations on the shorter weak link in the S/S’/S regime achieved at T = 4.25 K. We chose the parameters as follows. The normalized temperature parameter that describes the weak region is extracted from the measured critical temperature of the longest weak link  and the critical temperature of the banks

and the critical temperature of the banks  (see Fig. 1) as

(see Fig. 1) as  . The working temperature of 4.25 K corresponds to T = 0.817. For this temperature the anisotropy parameter is f(0.817) = 0.37, while the normalized length of the weak link is L/ξ(0.817) = 8.55. The width is W/ξ(0.817) = 42.7. Having checked that value for this dimension was not particularly relevant, we chose W/ξ(0.817) = 40 in the simulations. For other two relevant lengths [see inset of Fig. 3(a)] we chose LB/ξ(0.817) = 80 and LΔφ/ξ(0.817) = 70. When calculating time averaged electric field E = Δφ/LΔφ to build up the E(J) curves, we take the electrostatic potential difference Δφ inside the superconducting sample, a distance 5 ξ(T) away from the current injection boundaries at y = ± LB/2 = ± 40 ξ(T), as shown in Fig. 3(a). This corresponds to the four-probe configuration used in the experiment. Moreover, both current injection boundaries and voltage probes are well far from the S/S’ boundaries at y = ± L/2 = 4.275 ξ(T) of weak link region, as in the experiments.

. The working temperature of 4.25 K corresponds to T = 0.817. For this temperature the anisotropy parameter is f(0.817) = 0.37, while the normalized length of the weak link is L/ξ(0.817) = 8.55. The width is W/ξ(0.817) = 42.7. Having checked that value for this dimension was not particularly relevant, we chose W/ξ(0.817) = 40 in the simulations. For other two relevant lengths [see inset of Fig. 3(a)] we chose LB/ξ(0.817) = 80 and LΔφ/ξ(0.817) = 70. When calculating time averaged electric field E = Δφ/LΔφ to build up the E(J) curves, we take the electrostatic potential difference Δφ inside the superconducting sample, a distance 5 ξ(T) away from the current injection boundaries at y = ± LB/2 = ± 40 ξ(T), as shown in Fig. 3(a). This corresponds to the four-probe configuration used in the experiment. Moreover, both current injection boundaries and voltage probes are well far from the S/S’ boundaries at y = ± L/2 = 4.275 ξ(T) of weak link region, as in the experiments.

In the main panel of Fig. 3(a) we show the calculated time averaged electric field versus applied current, E(J), curve for H = 0. All relevant features of experimental curve at 4.25 K [see Fig. 1(b)] are reproduced, included the dissipative branch with resistivity ρQPL. To better understand such branch, in Fig. 3(b) we show the |ψ|2 at the center of weak link versus applied current density J. By increasing current from zero, the order parameter decreases up to a certain critical current density Jc. Above the critical current density Jc the order parameter is oscillating with time, and the dissipative branch shown in Fig. 3(a) is accessed. These oscillations of order parameter can be better appreciated in the inset of Fig. 3(b), where we show the profile of the squared order parameter along y-direction [reference frame is shown in the inset of panel (a)] at several times when the weak link is polarized on the dissipative branch of E(J) curve. The |ψ|2 pulsates with time and periodically vanishes at the center line of the weak link. The frequency of oscillation is found to increase as the current J is increased. These features are typical of the celebrated phase slip line solution9,10,11. The only difference with seminal previous reported simulations is that here the |ψ|2 pulsates between zero and a value that is depressed with respect to the one in the banks, or, in other words, here the periodic phase slippage is localized in a region of weakened superconductivity.

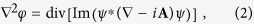

In Fig. 4(a) we show the calculated Jc(H), to be compared with the experimental Ic(B) shown in Fig. 2(a): the observed oscillations of critical current are qualitatively reproduced by the simple model of equations (1) and (2). The inset in Fig. 4(a) is a snapshots of |ψ|2 at the marked point of the Jc(H) curve. Here and in the following the snapshots are zooms of the full simulation region shown in Fig. 3(a), and show only parts of the fully superconducting S regions (banks) around the S’ region (weak link). The dashed lines mark the S/S’ boundaries of the weak link. The chosen point of the Jc(H) curve corresponds to the critical entry field4,43,49 Hs and is calculated setting J = 0, and gradually increasing the field until at H = Hs vortex matter enters the weak link. At chosen temperature two vortices nucleate to the edges, enter the weak link and rest in the central region. As can be inferred from the snapshot relative to static vortex matter, due to the confinement in the vertical direction, in our weak link only motion of a single vortex or a single vortex row can be established by a transport current J > Jc(H).

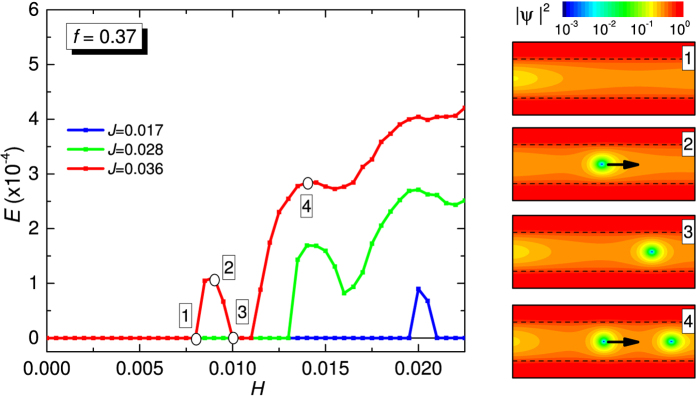

Figure 4. Abrikosov-Josephson vortex matter to Josephson-like vortex matter transition.

(a) Critical current of the weak link as a function of magnetic field, Jc(H). The inset is a snapshot of the squared order parameter, |ψ|2, at the marked point of Jc(H). Only a portion of full simulating region is shown. The dashed lines indicates the S/S’ boundaries of the weak link region. (b) E(J) curves for several values of the magnetic field H. The numbered panels are snapshots of |ψ|2 at the marked points of the E(J) curves. Vortex matter moves from left to right.

Finally, we should remark that a similar Jc(H) and vortex matter was reported in ref. 42 for a diffusive S/N/S junction with normalized dimensions comparable to our S/S’/S weak link, calculated in the framework of Usadel model. This suggests that an S/S’/S junction qualitatively resembles a diffusive S/N/S junction.

In Fig. 4(b) there are shown the calculated E(J) curves for several values of the magnetic field H. These curves should be compared with the experimental data reported in Fig. 2(b). As in the experiment, there are present the low resistivity almost linear dissipative branches followed by a transition, abrupt at low field and continuous at moderate fields, to a phase slip line branch. However, when looking at the voltage jumps present in the theoretical curves of Fig. 4(b), they are less severe here than in the experiments. This may be an indication that thermal effects play some role in the experiments and cannot be captured by our (isothermal) TDGL. For example, in the experiment we cannot claim with full confidence that the high voltage regime always corresponds to a genuine phase slippage since thermal effects can simply lead to a hot spot formation. As can be appreciated below, our simplified model qualitatively captures the relevant experimental features but thermal effects are neglected and this possibly limits some of our claims when direct comparison with experiment is made. The numbered panels in Fig. 4(b) are snapshots of |ψ|2 at the marked points of the E(J) curves. Vortex matter moves from left to right. As evidenced by snapshots (1) and (2) the low resistivity almost linear branches are accounted for moderately anisotropic vortex flow. Snapshots (2), (3), and (4) are relative at a field H where by increasing the current density the E(J) curve exhibits a continuous transition of the flux flow branch to the phase slip line branch. At low current [snapshot (2)] there is a single row of two anisotropic vortices moving from left to the right. As the current is increased the transition region is accessed [snapshot (3)]. Here the vortices in the row become more anisotropic and a river of depressed superconductivity starts to form. The river of depressed superconductivity is completely formed and strongly anisotropic vortices are surfing on it when the phase slip line branch is fully accessed by a further increase of the bias current.

The unidirectional vortex matter motion induced by magnetic field and large transport current shown in snapshot (4) is similar to the one first reported by Vodolazov and Peeters13 relatively to rearrangement of the vortex lattice due to instabilities of vortex flow. In that contest, the relevant dissipative branch was named “quasi-phase-slip line” and vortex matter involved was indirectly related to the vortex-based description of a phase slip line given by Andronov et al.11. Subsequently, other groups12,14,15,41,49 called the fast vortex matter involved in the high resistivity branch of thin plain mesoscopic strips “kinematic vortex”. Here, instead of a plain strip we have a weak link and, to avoid confusion, we prefer to use a nomenclature typical of weak links for the vortex matter involved in the dissipative branches. Our low resistivity branch and the related vortex matter resembles the one reported31,32,33 for strongly overdamped Josephson junctions in the regime of nonlocal electrodynamics achieved at very large critical current of the weak link, of the order of magnitude of the depairing current of the banks. Our weak link in the S/S’/S regime falls in that regime. In a seminal work33 Gurevich named the anisotropic vortex matter involved in such a regime “Abrikosov-Josephson vortex”. We adopt same terminology. In agreement with finding of Gurevich31,32,33, the Abrikosov-Josephson vortex expands its width as the current is increased (becomes more anisotropic) resulting in a E(J) linear at low currents but more and more nonlinear, with upward curvature, when current approaches the critical current of the weak link (our local depairing current). These peculiarity can be appreciated in Fig. 4(b). We should notice that description of Abrikosov-Josephson vortex dynamics was not based on full time-dependent Ginzburg Landau model and the order parameter was assumed to be independent of transport current. This is almost the case for our low resistivity dissipative branch, before the phase slip line branch is accessed at larger currents with associated appreciable depression of order parameter (see Fig. 3). Thus, the Abrikosov-Josephson vortex matter in snapshots (1), (2), and (3) evolves in a different vortex matter shown in snapshot (4) when the high resistivity branch is accessed. Noticing that at relatively large current the order parameter becomes dynamically strongly suppressed in S’ region [see Figs 3(b) and 5)], we can roughly assume that the S/S’/S system transits to a proximized S/N/S like system and consequently the moderately anisotropic Abrikosov-Josephson vortex transforms in a definitely anisotropic vortex that we will name “Josephson-like” vortex. As will be more clear below, this current-induced transition results in a higher speed of the vortex matter and fast increase of the voltage at some current.

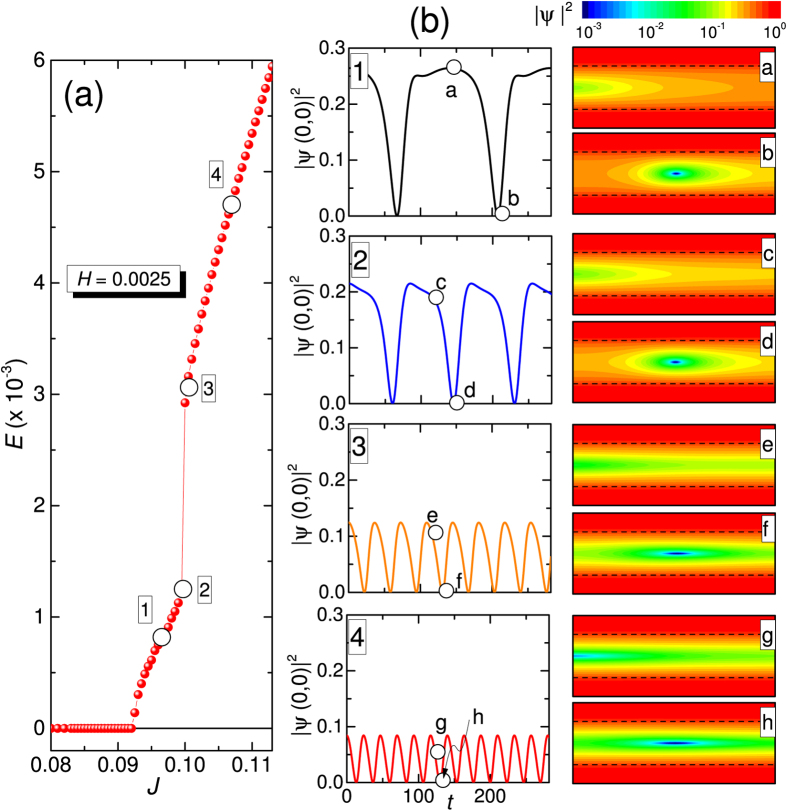

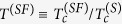

Figure 5. Josephson-like vortex is faster than Abrikosov-Josephson vortex.

(a) Calculated E(J) curves at H = 0.0025. (b) The numbered panels to the left show the oscillations of the squared order parameter at center of weak link versus time when we are on the marked points of the E(J) curve shown in (b). The lettered panels to the right are snapshots of |ψ|2 at times marked in the left panels.

So that, data in Fig. 2(b) can represent an indirect experimental evidence for Abrikosov-Josephson31,32,33 vortex flow at low bias current that transforms in Josephson-like vortex flow at larger bias currents.

We would notice that the shape of E(J) curves in Fig. 4(b) strongly reminds the one reported in our recent work49 on a plain mesoscopic strip in moderate magnetic fields driven by uniform transport current. Though there are similarities in the vortex dynamics, there are some differences due to the fact that here we are concerned with a single row of vortex excitations confined in a well defined channel of depressed superconductivity. For example, in the mesoscopic strip the nonlinear flux flow region just before the instability point was accounted for by a moving glassy lattice of isotropic vortex excitations (Abrikosov) while in the present weak link it is accounted for by more and more anisotropic (as the current is increased) excitations (Abrikosov-Josephson) moving in a single row. The high resistivity branch just after the instability point in the mesoscopic strip was accounted for by a rearrangement of the vortex lattice in a channel-like structure of slightly anisotropic excitations (kinematic vortices) surfing on rivers of depressed superconductivity not existent before. Here a single river of depressed superconductivity (S’ weak link region) is present also in the absence of magnetic field and transport current and, as explained above, is further suppressed when current is large enough so that the S/S’/S system effectively transits to a proximized S/N/S (Josephson like) system and consequently the moderately anisotropic vortex transforms in a definitely anisotropic vortex that we have named “Josephson-like” vortex.

To better explain the dynamical evolution of the Abrikosov-Josephson to the faster moving Josephson-like vortex involved in our S/S’/S weak link, in Fig. 5(a) we show the E(J) at the small field H = 0.0025, where both almost linear flux flow branch and phase slip line branch are present. In Fig. 5(b) the numbered panels to the left show the oscillations of the squared order parameter at center of weak link versus time when we are on the marked points of the E(J) curve shown in panel (a), while the lettered panels to the right are snapshots of |ψ|2 at times marked in the left panels. As can be seen, the almost linear branch at low currents [points (1) and (2)] is accounted for a single Abrikosov-Josephson vortex moving from left to the right. The |ψ|2(t) vanishes each time the vortex core passes for the center of the weak link and restores when vortex core is near one of the edges. Being involved only one vortex excitation, the oscillation frequency of the |ψ|2(t) is a measure of the mean velocity of the vortex, as it is also the measured E. From this we deduce that vortex velocity is almost linearly increased with current J from bias point (1) to bias point (2), similar to the ordinary vortex flow. However, when with a very small increment of current the phase slip branch is accessed at bias point (3) the mean velocity abruptly increases of about a factor three and further increases as the current is further increased at bias point (4). So, on the phase slip line branch the vortex matter (Josephson-like vortex) move faster than the Abrikosov-Josephson vortex involved in the almost linear lower resistivity flux flow branch. The dynamic Abrikosov-Josephson vortex involved in the flux flow branch is elongated along the direction of motion in our weak link, and its width increases with current31,32,33. However, the vortex core preserve a definite spatial extension, as can be appreciated from impulsive character of |ψ|2(t) waveform and the relevant stroboscopic snapshots of |ψ|2 when we are in this regime. Conversely, when the Josephson-like vortex is involved [points (3) and (4)], the vortex core extension becomes more and more undefined (increases) and the corpuscular nature of this vortex surfing on a river of further depressed superconductivity is more and more lost.

At very low magnetic field only one vortex excitation is involved both in the flux flow branch (Abrikosov-Josephson) and phase slip branch (Josephson-like). This allows us to estimates the velocities involved in our weak link directly from experimental V(I) curves in the very low field regime. In physical units we can estimate the mean velocity from the measured voltage and width of the weak link as v = WV/Φ0. From curves at 4.25 K reported in Fig. 2(b) we can assume that, e.g., the curve at B = 1.26 mT is accounted for a single vortex excitation. From this we see that typical voltage in the flux branch is VAJ ~ 10 μV, giving a velocity vAJ ~ 5 × 103 m/s. This velocity is of the order of magnitude we reported for ordinary Abrikosov vortex motion in mesoscopic strips49, though here it is sensibly larger, being a weak link involved. Conversely, from same curve, we read a typical voltage in the phase slip line branch VJl ~ 120 μV resulting in a velocity for the Josephson-like vortex vJl ~ 6 × 104 m/s, that is an order of magnitude larger than the Abrikosov-Josephson vortex, though lower than typical velocity of fastest known vortex excitation, i.e., the Josephson vortex in tunnel junctions26, where typically vJ ~ 3 × 106 m/s is observed.

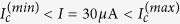

We conclude with a short analysis of magneto-resistance oscillations observed in the experiments. The calculated E(H) curves at different values of applied current density J are reported in Fig. 6. These curves should be compared with experimental data shown in Fig. 2(c). As in the experiments, the full reentrance of superconductivity (red curve) corresponds to  . The numbered panels are snapshots of |ψ|2 at the field and current values indicated in the E(H) curves. Arrows in panels (2) and (4) indicate direction of vortex matter motion. For red curve the current is fixed at J = 0.036. At H = 0 there are no vortices in the weak link. By increasing the field, a current-assisted Abrikosov-Josephson vortex nucleation at left edge is achieved at a critical value [point (1)] and vortex moves under the influence of Lorentz force producing dissipation (E ≠ 0). By increasing the magnetic field, the vortex is first accelerated [point (2)] and then stopped [point (3)] near the right edge at some critical value of magnetic field, so that the fully superconducting state (E = 0) is restored. The vortex stays at rest, due to confining potential of magnetic field, until a further increase of magnetic field produces a new vortex nucleation at left edge. Due to the repulsive inter-vortex interaction, the new vortex expels the static vortex and dissipation is again established [point (4)].

. The numbered panels are snapshots of |ψ|2 at the field and current values indicated in the E(H) curves. Arrows in panels (2) and (4) indicate direction of vortex matter motion. For red curve the current is fixed at J = 0.036. At H = 0 there are no vortices in the weak link. By increasing the field, a current-assisted Abrikosov-Josephson vortex nucleation at left edge is achieved at a critical value [point (1)] and vortex moves under the influence of Lorentz force producing dissipation (E ≠ 0). By increasing the magnetic field, the vortex is first accelerated [point (2)] and then stopped [point (3)] near the right edge at some critical value of magnetic field, so that the fully superconducting state (E = 0) is restored. The vortex stays at rest, due to confining potential of magnetic field, until a further increase of magnetic field produces a new vortex nucleation at left edge. Due to the repulsive inter-vortex interaction, the new vortex expels the static vortex and dissipation is again established [point (4)].

Figure 6. Magnetoresistance oscillations induced by strongly confined vortex matter.

Time-averaged electric field E as a function of magnetic field H for different values of applied current density J. The numbered panels are snapshots of |ψ|2 at the field and current values indicated in the E(H) curves. Arrows in panels (2) and (4) indicate direction of vortex matter motion.

The shape of E(H) oscillations, stemming from Jc(H) modulations, strongly reminds the one reported in a recent numerical work41 by Berdiyorov et al. on weak links. In that case a rather short and narrow weak link was addressed, but also if our real weak link is slightly longer and wider, here we confirms that involved dynamics is practically the same as the one described by Berdiyorov et al., and it is typical3,4,41 of strong confinement of a very small number of vortices (here only one or two). In this sense, the data in Fig. 2(c) are the experimental demonstration of the effect predicted by Berdiyorov et al. specifically for a weak link, and add further experimental evidence5,6,7,8 for the peculiarities3,4,41 of magneto-transport in strongly confined vortex matter systems.

Methods

Both thin Nb and Py films were deposited by rf magnetron sputtering in a high vacuum system with a base pressure of 2 × 10−7 Torr at room temperature. The geometry of both films was defined by lift-off through a resist mask made by electron beam lithography. To define the weak links, first a 30-nm thick Nb film is deposited onto a Si/SiO2 substrate and patterned with a multi contact geometry. Then, after a light sputter etch of the Nb layer (3 min at 400 V, enough to eliminate the thin thermal oxide grown after exposition to air) 30-nm thick Py stripes are deposited to locally cross the Nb strip. A micrograph of final sample layout is shown in the inset of Fig. 1(a). The horizontal Py stripes are all 10 μm long and their widths are 0.2 μm, 0.4 μm, 0.6 μm, and 0.8 μm. The vertical section of Nb strip is 1 μm wide, so that all weak links are 1 μm wide, and the lateral fingers, used for voltage contacts, are 5 μm apart. The black lettering in the micrograph shows the current and voltage electrodes used for four-point electrical measurements.

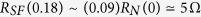

We notice that due to the presence of a Nb/Py bilayer with variable length LSF = xLV between the fixed voltage probes distance LV = 5 μm the fully normal state resistance is not expected to be exactly the same for all samples, as it is in fact observed in Fig. 1(a). The Nb banks have variable length LS = (1 − x)LV and their resistance is RS(x) = (1 − x)RN(0) with  the resistance of reference sample. Resistivities of our Nb and Py are very similar, the thickness is the same, and a good electrical contact between Py and Nb layer was intentionally made. Thus, the resistance of the weak link portion is approximately RSF(x) = (x/2)RN(0). At

the resistance of reference sample. Resistivities of our Nb and Py are very similar, the thickness is the same, and a good electrical contact between Py and Nb layer was intentionally made. Thus, the resistance of the weak link portion is approximately RSF(x) = (x/2)RN(0). At  both banks and SF regions are normal so that we measure a resistance RN(x) = (1 − x/2)RN(0) decreasing as the weak link region length is increased, in agreement with results shown in Fig. 1(a). Conversely, in the temperature range

both banks and SF regions are normal so that we measure a resistance RN(x) = (1 − x/2)RN(0) decreasing as the weak link region length is increased, in agreement with results shown in Fig. 1(a). Conversely, in the temperature range  only the SF region is normal and, apart for corrections due to lateral proximity effect, a resistance RSF(x) ~ (x/2)RN(0) increasing with length of the weak link should be observed, in qualitative agreement with results of Fig. 1(a). Particularly, for the longest weak link is

only the SF region is normal and, apart for corrections due to lateral proximity effect, a resistance RSF(x) ~ (x/2)RN(0) increasing with length of the weak link should be observed, in qualitative agreement with results of Fig. 1(a). Particularly, for the longest weak link is  and we measure in the plateau region a resistance of the SF bilayer 4 Ω < RSF < 6 Ω. Such a figure is consistent with

and we measure in the plateau region a resistance of the SF bilayer 4 Ω < RSF < 6 Ω. Such a figure is consistent with  , the resistance expected when the proximity effect in the vertical direction (depletion of superconductivity) affects the entire thickness and surface of the Nb below the Py.

, the resistance expected when the proximity effect in the vertical direction (depletion of superconductivity) affects the entire thickness and surface of the Nb below the Py.

To minimize thermal effects, measurements were made in a liquid Helium dewar and the Si/SiO2 substrate was glued with silver paint to a massive copper sample holder. The voltage-current curves were acquired in a reasonably short time (typically 50 s) and permanence in dissipative states that could generate thermal instability or hot spots was carefully minimized. Electrical interference was minimized filtering all cables with RC filters and external magnetic field interference was minimized by means of a high permeability cryoperm shield. Very low noise voltage-current curves were recorded using a current source/nanovoltmeter combo, and a similar electronics already used for voltage-spectral density characterizations55. Stable low magnetic field was applied by means of a copper solenoid held in Helium bath biased by a precision current source.

From the Ic(B), recorded at T = 4.25 K, shown in Fig. 2(a) we can gain information on the electrical width26 of the weak link with respect to the Josephson penetration length λj26 often used for weak links. The first lobe extrapolates to Ic = 0 at a critical field26

. Assuming the presence of a Josephson coupling, we can approximately estimate the normalized electrical width

. Assuming the presence of a Josephson coupling, we can approximately estimate the normalized electrical width  of our weak link using same formula26,40 for λj used in tunnel junctions. From the measured critical current density Jc at zero field and the magnetic penetration26

d = 2λ + L, where L = 0.2 μm is the length of the weak link and λ is the temperature-dependent London penetration depth of the Nb thin film (see below), we estimate λj ≈ 0.25 μm, resulting in a normalized width

of our weak link using same formula26,40 for λj used in tunnel junctions. From the measured critical current density Jc at zero field and the magnetic penetration26

d = 2λ + L, where L = 0.2 μm is the length of the weak link and λ is the temperature-dependent London penetration depth of the Nb thin film (see below), we estimate λj ≈ 0.25 μm, resulting in a normalized width  . On the basis of this, we expect that a weak magnetic field can induce a small number (up to to a maximum of four) of vortex excitations in the weak link. In numerical simulations shown in Fig. 4(a) we see that at the entry field (critical field) two almost isotropic (static) vortices are present in the weak link, meaning that the effective magnetic flux Φ(B) = BAe, should be practically equal (in physical units) to 2Φ0 at B = B0. From this we can estimate an effective magnetic area of the weak link as

. On the basis of this, we expect that a weak magnetic field can induce a small number (up to to a maximum of four) of vortex excitations in the weak link. In numerical simulations shown in Fig. 4(a) we see that at the entry field (critical field) two almost isotropic (static) vortices are present in the weak link, meaning that the effective magnetic flux Φ(B) = BAe, should be practically equal (in physical units) to 2Φ0 at B = B0. From this we can estimate an effective magnetic area of the weak link as  , that is found to be consistent with the one expected by the relation26

, that is found to be consistent with the one expected by the relation26

using real physical dimensions of the weak link and noticing that at 4.25 K for our Nb is

using real physical dimensions of the weak link and noticing that at 4.25 K for our Nb is  . As the resistance based check, this magnetic check confirms that the effective area of the realized weak link is the one geometrically designed, and no other mechanisms beside (full) proximity effect are relevant.

. As the resistance based check, this magnetic check confirms that the effective area of the realized weak link is the one geometrically designed, and no other mechanisms beside (full) proximity effect are relevant.

In model equations (1), and (2) the coordinates are in units of coherence length at working temperature  , with temperature T in units of critical temperature of banks

, with temperature T in units of critical temperature of banks  ; time is measured in units of the relaxation time τ(T) = τ(0)/(1 − T); the order parameter is in units of

; time is measured in units of the relaxation time τ(T) = τ(0)/(1 − T); the order parameter is in units of  ; the vector potential is measured in units Φ0/2πξ(T); the electrostatic potential is in units of

; the vector potential is measured in units Φ0/2πξ(T); the electrostatic potential is in units of  . In these units the magnetic field is scaled with Hc2(T) = Φ0/2πξ(T)2 and the current density with j(T) = cΦ0/8π2λ(T)2ξ(T), with

. In these units the magnetic field is scaled with Hc2(T) = Φ0/2πξ(T)2 and the current density with j(T) = cΦ0/8π2λ(T)2ξ(T), with  . In our numerical integration of equations (1) and (2) we make use of the “bridge” boundary condition4,56,57 in the y-direction: in a region of length 2.5 ξ at the ends of the banks at y = ± LB/2 [see insets of Fig. 3(a)] the TDGL equations are reduced to (∂t + iϕ)ψ = 0, ∇2ϕ = 0 with boundary conditions ∂yψ = 0 and ∂yϕ = −J, where J is the uniformly injected bias current density. This mimics a situation where in the region of interest the current is injected from superconducting contacts, as it is in the experiment [see insets of Fig. 1]. In the x-direction, an insulator-superconductor boundary condition (i∂x + Ax)ψ = 0 is used for the order parameter and the Neumann boundary condition ∂xϕ = 0 is applied for the electrostatic potential. The initial conditions are |ψ| = 1 and ϕ = 0. We apply a finite-difference representation for the order parameter ψ and the electrostatic potential ϕ on a uniform Cartesian space grid and use the link variable approach58. We employ a Dormand-Prince embedded method for ordinary differential equations (an embedded Runge-Kutta integrator of order 8 with stepsize control) to find ψ. The electrostatic potential ϕ is obtained by the Fourier transform method. When dc quantities are involved, the behaviour of the system is studied on a large time scale when time-averaged values no longer depend on time.

. In our numerical integration of equations (1) and (2) we make use of the “bridge” boundary condition4,56,57 in the y-direction: in a region of length 2.5 ξ at the ends of the banks at y = ± LB/2 [see insets of Fig. 3(a)] the TDGL equations are reduced to (∂t + iϕ)ψ = 0, ∇2ϕ = 0 with boundary conditions ∂yψ = 0 and ∂yϕ = −J, where J is the uniformly injected bias current density. This mimics a situation where in the region of interest the current is injected from superconducting contacts, as it is in the experiment [see insets of Fig. 1]. In the x-direction, an insulator-superconductor boundary condition (i∂x + Ax)ψ = 0 is used for the order parameter and the Neumann boundary condition ∂xϕ = 0 is applied for the electrostatic potential. The initial conditions are |ψ| = 1 and ϕ = 0. We apply a finite-difference representation for the order parameter ψ and the electrostatic potential ϕ on a uniform Cartesian space grid and use the link variable approach58. We employ a Dormand-Prince embedded method for ordinary differential equations (an embedded Runge-Kutta integrator of order 8 with stepsize control) to find ψ. The electrostatic potential ϕ is obtained by the Fourier transform method. When dc quantities are involved, the behaviour of the system is studied on a large time scale when time-averaged values no longer depend on time.

From the slope close to Tc of the upper critical field μ0Hc2(T) of the reference strip we estimate59 for our sputtered Nb film a coherence length  . From resistivity and critical temperature we estimate51 a London penetration depth

. From resistivity and critical temperature we estimate51 a London penetration depth  , resulting in a Ginzburg-Landau parameter

, resulting in a Ginzburg-Landau parameter  . So, our thin Nb strip is definitively a type-II superconductor. Moreover, a Pearl length Λ ≈ 2.1 μm is estimated for our 30-nm thick Nb at T = 0 that increases at Λ ≈ 4.2 μm at reduced temperature T ~ 0.8. So, noticing that the strip width is W = 1 μm and that experiments were performed at T ≥ 0.8 the conditions for mesoscopic regime are reasonably satisfied for our strips.

. So, our thin Nb strip is definitively a type-II superconductor. Moreover, a Pearl length Λ ≈ 2.1 μm is estimated for our 30-nm thick Nb at T = 0 that increases at Λ ≈ 4.2 μm at reduced temperature T ~ 0.8. So, noticing that the strip width is W = 1 μm and that experiments were performed at T ≥ 0.8 the conditions for mesoscopic regime are reasonably satisfied for our strips.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Carapella, G. et al. Current driven transition from Abrikosov-Josephson to Josephson-like vortex in mesoscopic lateral S/S’/S superconducting weak links. Sci. Rep. 6, 35694; doi: 10.1038/srep35694 (2016).

Acknowledgments

Financial support from PON Ricerca e Competitivitá 2007–2013 under Grant Agreement PON NAFASSY is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Author Contributions G.C. directed the project, performed experiments, and wrote the manuscript. P.S. and S.P. performed sample patterning and numerical simulations. C.B. contributed to organization and presentation of results. M.G. prepared figures. All authors contributed to the theoretical interpretation, discussed the results and implications, and commented on the manuscript by reviewing it accurately.

References

- Tinkham M. Introduction to Superconductivity (McGraw-Hill, Singapore, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- Blatter G., Feigel’man M. V., Geshkenbein V. B., Larkin A. I. & Vinokur V. M. Vortices in high-temperature superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125–1388 (1994). [Google Scholar]

- Berdiyorov G. R. et al. Magnetoresistance oscillations in superconducting strips: a Ginzburg-Landau study. Phys. Rev. B 86, 224504 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Vodolazov D. Y. Vortex-induced negative magnetoresistance and peak effect in narrow superconducting films. Phys. Rev. B 88, 014525 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Ilin K. et al. Critical current of Nb, NbN, and TaN thin-film bridges with and without geometrical nonuniformities in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 89, 184511 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Berdiyorov G. R. et al. Large magnetoresistance oscillations in mesoscopic superconductors due to current-excited moving vortices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 057004 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba R. et al. Magnetic field-induced dissipation-free state in superconducting nanostructures. Nature Commun. 4, 1437 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan-Wall T., Leith B., Hartman N., Rahman A. & Marković N. Measurement of critical currents of superconducting aluminum nanowires in external magnetic fields: evidence for a Weber blockade. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 077002 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L. & Baratoff A. Lossless and dissipative current-carrying states in quasi-one-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 38, 518–521 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L. & Watts-Tobin R. J. Theory of dissipative current-carrying states in superconducting filaments. Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 1041–1044 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- Andronov A., Gordion I., Kurin V., Nefedov I. & Shereshevsky I. Kinematic vortices and phase slip lines in the dynamics of the resistive state of narrow superconductive thin film channels. Physica C 213, 193–199 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Sivakov A. G. et al. Josephson behavior of phase-slip lines in wide superconducting strips. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 267001 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodolazov D. Y. & Peeters F. M. Rearrangement of the vortex lattice due to instabilities of vortex flow. Phys. Rev. B 76, 014521 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Berdiyorov G. R., Milošević M. V. & Peeters F. M. Kinematic vortex-antivortex lines in strongly driven superconducting stripes. Phys. Rev. B 79, 184506 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Silhanek A. V. et al. Formation of stripelike flux patterns obtained by freezing kinematic vortices in a superconducting Pb film. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 017001 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdiyorov G. et al. Dynamics of current-driven phase-slip centers in superconducting strips. Phys. Rev. B 90, 054506 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Bawa A., Jha R. & Sahoo S. Tailoring phase slip events through magnetic doping in superconductor-ferromagnet composite films. Sci. Rep. 5, 13459 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van de Vondel J. et al. Vortex Core Deformation and Stepper-Motor Ratchet Behavior in a Superconducting Aluminum Film Containing an Array of Holes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 137003 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano N. Evidence for macroscopic quantum tunneling in one-dimensional superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 61, 2137–2140 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaikin A. D., Golubev D. S., van Otterlo A. & Zimányi G. T. Quantum phase slips and transport in ultrathin superconducting wires. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1552–1555 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Bezryadin A., Lau C. N. & Tinkham M. Quantum suppression of superconductivity in ultrathin nanowires. Nature 404, 971–974 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trezza M. et al. Nonlinear current-voltage characteristics due to quantum tunneling of phase slips in superconducting Nb nanowire networks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 252601 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Annunziata A. J. et al. Reset dynamics and latching in niobium superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors. J. Appl. Phys. 108, 084507 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Barone C. et al. Probing transport mechanisms of BaFe2As2 superconducting films and grain boundary junctions by noise spectroscopy. Sci. Rep. 4, 6163 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gennes P. G. Superconductivity of Metals and Alloys (Addison-Wesley, Redwood City, California, 1989). [Google Scholar]

- Barone A. & Paterno G. Physics and Applications of the Josephson Effect (Wiley, New York, 1982). [Google Scholar]

- Likharev K. K. Superconducting weak links. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 101–159 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- Bergeret F. S., Volkov A. F. & Efetov K. B. Odd triplet superconductivity and related phenomena in superconductor-ferromagnet structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 1321–1373 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keizer R. S. et al. A spin triplet supercurrent through the half-metallic ferromagnet CrO2. Nature 439, 825–827 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heersche H. B., Jarillo-Herrero P., Oostinga J. B., Vandersypen L. M. K. & Morpurgo A. F. Bipolar supercurrent in graphene. Nature 446, 56–59 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikhzada A. & Gurevich A. Fragmentation of fast Josephson vortices and breakdown of ordered states by moving topological defects. Sci. Rep. 5, 17821 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A. et al. Flux flow of Abrikosov-Josephson vortices along grain boundaries in high-temperature superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 097001 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurevich A. Nonlinear viscous motion of vortices in Josephson contact. Phys. Rev. B 48, 12857 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boris A. A. et al. Evidence for nonlocal electrodynamics in planar Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 117002 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roditchev D. et al. Direct observation of Josephson vortex cores. Nature Phys. 11, 332–337 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Buzdin A. I. Proximity effects in superconductor-ferromagnet heterostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 935–976 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Fominov Ya. V., Chtchelkatchev N. M. & Golubov A. A. Nonmonotonic critical temperature in superconductor/ferromagnet bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 66, 014507 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Vávra O., Pfaff W. & Strunk Ch. Planar S-(S/F)-S Josephson junctions induced by the inverse proximity effect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 062501 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Lin L. K., Huang S. Y., Huang J. H. & Lee S. F. Nb lateral Josephson junctions induced by a NiFe cross strip. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 242601 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Vávra O., Pfaff W., Monaco R., Aprili M. & Strunk C. Current-controllable planar S-(S/F)-S Josephson junction. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 072602 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Berdiyorov G. R. et al. Dynamic and static phases of vortices under an applied drive in a superconducting stripe with an array of weak links. Eur. Phys. J. B 85, 130 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas J. C. & Bergeret F. S. Magnetic Interference Patterns and Vortices in Diffusive SNS Junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 217002 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clem J. R., Mawatari Y., Berdiyorov G. R. & Peeters F. M. Predicted field-dependent increase of critical currents in asymmetric superconducting nanocircuits. Phys. Rev. B 85, 144511 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Granata V., Russo F. & Costabile G. Bistable Abrikosov vortex diode made of a Py-Nb ferromagnet-superconductor bilayer structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 94, 242504 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Sabatino P. & Costabile G. Asymmetry, bistability, and vortex dynamics in a finite-geometry ferromagnet-superconductor bilayer structure. Phys. Rev. B 81, 054503 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino P., Carapella G. & Gombos M. Preferentially directed flux motion in a very thin superconducting strip with nanostructured profile. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 083909 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Sabatino P. & Costabile G. Considerable asymmetry of the critical current in a niobium thin strip of plano-convex section. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 053912 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Sabatino P. & Gombos M. Superconducting slab in an antisymmetric magnetic field: vortex-antivortex dynamics. Physica C 515, 7–14 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi G. et al. Speed limit to the Abrikosov lattice in mesoscopic superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 92, 024513 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Clem J. R. & Berggren K. K. Geometry-dependent critical currents in superconducting nanocircuits. Phys. Rev. B 84, 174510 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Ilin K. et al. Critical current of Nb, NbN, and TaN thin-film bridges with and without geometrical nonuniformities in a magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 89, 184511 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Adami O. A. et al. Current crowding effects in superconducting corner-shaped Al microstrips. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 052603 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Clinton T. W. & Johnson M. Mesoscopic magnetoquenched superconducting valve. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70, 1170–1172 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Russo F. & Costabile G. Low-field transport measurements in superconducting Co/Nb/Co trilayers. Phys. Rev. B 78, 104529 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Barone C. et al. Nonequilibrium fluctuations as a distinctive feature of weak localization. Sci. Rep. 5, 10705 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carapella G., Sabatino P. & Costabile G. A single Abrikosov vortex trapped in a mesoscopic superconducting cylindrical surface. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 23, 435701 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino P., Carapella G. & Costabile G. Magneto-transport properties of curved mesoscopic superconducting strips. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 24, 125007 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Winiecki T. & Adams C. S. Time-dependent Ginzburg-Landau simulations of the voltage-current characteristic of type-II superconductors with pinning. Phys. Rev. B 65, 104517 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Sabatino P., Cirillo C., Carapella G., Trezza M. & Attanasio C. High field vortex matching effects in superconducting Nb thin films with a nanometer-sized square array of antidots. J. Appl. Phys. 108, 053906 (2010). [Google Scholar]