Abstract

We present results for direct bio‐electrocatalytic reduction of CO2 to C1 products using electrodes with immobilized enzymes. Enzymatic reduction reactions are well known from biological systems where CO2 is selectively reduced to formate, formaldehyde, or methanol at room temperature and ambient pressure. In the past, the use of such enzymatic reductions for CO2 was limited due to the necessity of a sacrificial co‐enzyme, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), to supply electrons and the hydrogen equivalent. The method reported here in this paper operates without the co‐enzyme NADH by directly injecting electrons from electrodes into immobilized enzymes. We demonstrate the immobilization of formate, formaldehyde, and alcohol dehydrogenases on one‐and‐the‐same electrode for direct CO2 reduction. Carbon felt is used as working electrode material. An alginate–silicate hybrid gel matrix is used for the immobilization of the enzymes on the electrode. Generation of methanol is observed for the six‐electron reduction with Faradaic efficiencies of around 10 %. This method of immobilization of enzymes on electrodes offers the opportunity for electrochemical application of enzymatic electrodes to many reactions in which a substitution of the expensive sacrificial co‐enzyme NADH is desired.

Keywords: bio-electrocatalysis, CO2 reduction, dehydrogenase, enzymes, immobilization

Introduction

Recycling of CO2 to useful fuels and/or to technology‐relevant organic molecules offers great potential to decrease atmospheric greenhouse gases and to provide sustainable carbon cycles.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 There are several ways to chemically utilize and convert CO2 into different carbohydrates. Furthermore, to make artificial fuels by reduction of CO2 using renewable energies (solar and wind) is regarded as one of the feasible routes to convert renewable energies into chemical energy and thus store them in a transportable way.3, 6, 7, 8, 9 Equations (1)–(6) show possible reduction routes of CO2 towards the synthesis of C1 chemicals and the corresponding theoretical potentials (in aqueous solutions at pH7) required for the reaction.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

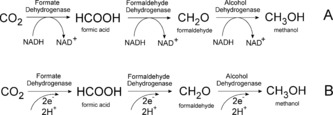

However, the potentials depicted in Equations (1)–(6) are more negative in real experiments due to overpotentials. Therefore, to overcome these energy barriers, catalysts are required. To date, the use of enzymes as natural catalytic systems in these approaches for generating artificial fuels utilizes co‐enzymes, such as nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), as energy carrier for the reduction of CO2. That implies that for every two‐electron reduction step of CO2 in a three‐step cascade and in the presence of the three dehydrogenases formate dehydrogenase (FateDH), formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FaldDH), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) one NADH molecule is oxidized to NAD+ (Scheme 1 A).

Scheme 1.

Reduction mechanisms for CO2 catalyzed by dehydrogenases. Three‐step reduction of CO2 to methanol using NADH as sacrificial co‐enzyme (A) and via a direct electron transfer to the enzyme without any co‐enzyme (B).

In contrast to the utilization of NADH as electron supply, Scheme 1 B shows the direct injection of electrons into the same dehydrogenases. As reported in various studies, the three dehydrogenases can be used in combination to achieve a conversion of CO2 all the way to methanol.10, 11, 12

Enzymatic reduction reactions can be carried out at ambient temperatures and pressures and under milder conditions compared to the industrial reduction of CO2 using H2, which occurs at high temperatures (above 300 °C) and under high pressures.13 Therefore, the use of enzymes would be highly attractive for industry. For large‐scale industrial applications, however, the sacrificial reduction agent NADH is neither feasible and practical nor economical. A direct electrochemical method for CO2 reduction using enzymes can open the easy way to store renewable electrical energy (such as from photovoltaic panels) as chemical energy (artificial fuels such as methanol and methane).

Different approaches for electrochemical CO2 reduction to fuels and valuable chemicals have also been discussed.14, 15, 16, 17 Organic semiconductors,18 organic transition‐metal complexes,19 catalytic organic molecules,20 metal electrodes,15, 21, 22, 23 and nanoparticles24 were explored for electrochemical CO2 reduction processes. However, these artificial catalytic systems are not as selective as natural catalysts and need further development.

Compared to other catalytic systems, biocatalysts are highly selective according to the product generated, which results in a high yield and reproducibility for CO2 reduction. As reported, dehydrogenases, with the aid of the co‐enzyme NADH, are capable of producing acids, aldehydes, and alcohols from CO2 as carbon source.10, 11, 12

For this study, we focused especially on the bio‐electrochemical approach of CO2 reduction to methanol using dehydrogenases without any co‐enzymes (such as NADH) or any electron mediator needed.

As a known technique, enzymes are immobilized in matrices to ensure high stability of the enzyme and high activity and reusability of the biocatalysts. First approaches of enzyme immobilization for CO2 reduction were reported by Heichal‐Segal et al. using alginate–silicate gel matrices for glucosidase immobilization to prevent it from thermal and chemical denaturation.25 Later, Aresta et al. investigated enzymes immobilized in agar as well as polyacrylamide, pumice, and zeolite materials with regard to stability and activity of the carboxylase to be used for the synthesis of benzoic acid from phenol and CO2.26, 27 Obert and Dave first presented the immobilization of dehydrogenases for chemical CO2 reduction in silica sol–gel matrices.10 Furthermore, the groups of Lu and Wu also investigated the immobilization of dehydrogenases in beads of an alginate–silica hybrid gel for the chemical CO2 reduction to methanol and formate.12, 28 In the work of Dibenedetto et al., NADH regeneration and the use of new hybrid technologies for the conversion of CO2 to methanol with the dehydrogenase cascade were investigated by merging biological and chemical technologies.29 Immobilization in gels and gel beads yields a large surface area, high stability, and reduces costs due to possible reusability. In all these enzymatic CO2 reduction approaches using dehydrogenases, NADH was used as electron and proton donor (see Scheme 1 A). However, in experiments using NADH as electron donor, NADH is irreversibly converted to its oxidized form NAD+ as a sacrificial co‐factor. This irreversible NADH oxidation limits enzyme applications for CO2 reduction to small‐scale experiments due to high costs for co‐factor synthesis and regeneration. Therefore, an appropriate substitution for co‐enzymes is necessary. Particularly, the application of electrochemical processes and the direct injection of electrons into enzymes instead of NADH as electron donor is of high interest. Addo et al. showed that NADH could be regenerated bio‐electrocatalytically using electrochemically addressed dehydrogenases.30 Furthermore, Kuwabata et al. presented the electrochemical reduction of CO2 to methanol using dehydrogenases and methylviologen as well as pyrroloquinoline quinone as electron mediators.31 Reda et al. then successfully demonstrated the electrochemical reduction of CO2 using formate dehydrogenase adsorbed on glassy carbon without the need of any electron shuttle, yielding Faradaic efficiencies of 97 % and higher.32

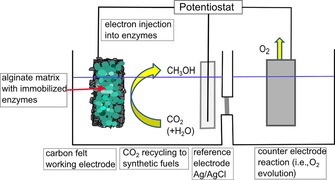

Herein, we report the direct electrochemical reduction of CO2 to methanol utilizing dehydrogenases immobilized on carbon felt electrodes (Figure 1) without requiring any co‐enzyme or mediator. This approach substitutes the expensive electron donor NADH by directly injecting electrons into the enzymes.

Figure 1.

Representation of the electrochemical CO2 reduction using enzymes. Electrons are injected directly into the enzymes, which are immobilized in an alginate–silicate hybrid gel (green) on a carbon‐felt working electrode. CO2 is reduced at the working electrode. Oxidation reactions take place at the counter electrode.

Results and Discussion

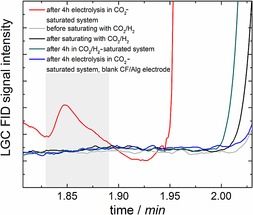

A carbon felt electrode modified with alginate containing the three dehydrogenases was investigated for electrolysis and analysis in liquid‐injection gas chromatography (LGC) first in a N2‐saturated system. The same electrode was then used for electrolysis in a CO2‐saturated system. It was observed that a peak in LGC at a retention time at around 1.85 min for methanol was observed only when CO2 was present. To exclude that this formation of methanol is due to in situ generation of H2 from water splitting (observed by gas chromatography analysis of the headspace before and after performed electrolysis experiments) and the subsequent reaction of the H2 with CO2, the enzyme‐modified electrode was simply stored in a CO2‐ and H2‐saturated compartment without any potential applied or electrolysis performed. Again, no methanol generation was detected, which indicates that the reduction of CO2 takes place because of bio‐electrocatalytic processes utilizing the dehydrogenases immobilized on the electrode. For comparison, an identically prepared electrode but without any enzymes added was used for electrolysis in a CO2‐saturated system, which did not result in methanol generation as well; this supports that the enzymes are catalytically active in the bio‐electrocatalytic process at the electrode.

Figure 2 compares samples analyzed using LGC. Identification of the peak corresponding to methanol was achieved by performing standard calibration by comparing the sample to distinct volumes of methanol. Quantification according to standard calibration delivered around 0.15 ppm of methanol produced after electrolysis in a CO2‐saturated system using the enzyme‐modified electrode.

Figure 2.

Comparison of chromatograms from LGC. A peak cannot be observed for samples without electrolysis and for which the enzyme electrode was simply stored in a CO2‐ or H2‐saturated solution. A peak at the methanol retention time of 1.85 min was only observed for samples that were analyzed after 4 h of electrolysis at −1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl in a CO2‐saturated system using an enzyme‐containing electrode, yielding 0.15 ppm methanol according to calibration.

Performing the same experiment for formaldehyde using an equivalent standard solution did not give rise to a peak corresponding to formaldehyde. Further analysis of samples was performed using capillary ion chromatography (CAP‐IC) to also investigate the formation of formate as reduction product; no significant amounts were detected.

In all CO2‐saturated systems used in this study, methanol was only generated in the presence of dehydrogenases immobilized on the electrode and when electrolysis was performed.

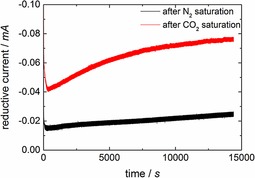

Potentiostatic electrolysis experiments were performed at −1.2 V versus Ag/AgCl for 4 h. This voltage was chosen because methanol formation was only observed above −1 V. Figure 3 shows the current–time plots of the electrolysis experiments using an enzyme‐modified electrode in the N2‐ or CO2‐saturated system. A remarkable increase in reductive current for the CO2‐saturated solution (red curve) compared to the N2 saturated solution (black curve; here, the current is most likely due to the water splitting reaction as described above) is observed.

Figure 3.

Current–time curves for the electrolysis of a carbon felt electrode modified with enzyme‐containing alginate. Experiments were conducted potentiostatically at −1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl in a N2‐ or CO2‐saturated electrolyte solution. Current behavior over time for the N2‐saturated system shows a certain basic current caused by competing reactions taking place independently from the CO2 reduction for all electrochemical experiments.

The total number of electrons passed during the potentiostatic experiments was determined by integrating the current–time curve; from this, the number of electrons passing during electrolysis in the N2‐saturated system was subtracted. This number was assumed to be caused only by CO2 reduction and could, therefore, be divided by 6, accounting for the number of electrons consumed for the reduction reaction to methanol [see Eq. (5)]. During electrolysis, 0.64 C were consumed. In LGC, around 0.15 ppm (0.005 mmol L−1) methanol was detected for the electrolysis experiment at a constant potential of −1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), which corresponds to a Faradaic efficiency of around 10 %.

In contrast to natural and nature‐inspired processes using NADH as electron and proton donor, there is little information about the mechanism for direct electrochemical application of enzymes in electrocatalytic systems without the use of co‐enzymes. However, for our electrochemical approach we expect a direct charge transport to the enzyme but without requiring the presence of NADH.

Conclusions

Direct injection of electrons into immobilized dehydrogenases without any sacrificial co‐enzyme delivered for the electrochemical CO2 reduction to methanol around 0.15 ppm. Faradaic efficiencies of around 10 % were obtained. These results show for the first time that all three dehydrogenases can directly be addressed with electrochemistry without requiring any sacrificial mediator or electron donor such as NADH.

Direct electrochemical CO2 reduction with a significant amount of charge consumed for the reduction of CO2 to methanol using these enzyme‐modified electrodes offers a selective, reproducible, and mild method for the production of artificial fuels and opens the way to biodegradable and sustainable energy conversion. The reported efficiencies for the reduction of CO2 to methanol reported herein are conservative estimates. Within the electrochemical approaches presented in literature, these values are on the order of magnitude of efficiencies for example presented by Cole et al. by using pyridinium (faradaic efficiencies of about 22 % relative to methanol generation).20 The system we present here is continuously optimized, and efficiencies up to 30 % could be reached in some experiments. Such bio‐electrocatalytic approaches offer the possibility for a biocompatible and very selective CO2 reduction to a single product at mild operation conditions.

Experimental Section

The enzymes formate dehydrogenase (FateDH), formaldehyde dehydrogenase (FaldDH), and alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) were immobilized on an electrode using an alginate–silica hybrid gel. The working electrode consisting of carbon felt (CF) purchased from SGL Carbon GmbH had a size of 2×0.6×0.6 cm3. Carbon felt offers good conductivity, high surface area, and has sponge‐like properties. For the electrochemical conversion of CO2, dehydrogenases were immobilized on carbon felt electrodes using an alginate–silicate hybrid gel. The alginate–silicate hybrid gel matrix was prepared by dissolving alginic acid sodium salt (0.1 g ) in water (3.5 mL, 18.2 MΩ) and phosphate buffer (1 mL ). For sufficient cross‐linking, of tetraethyl orthosilicate (500 μL) was added. Then FateDH (from Candida Boidinii, lyophilized powder, 0.88 units mg−1 solid; ∼20 mg), FaldDH (from Pseudomonas putida, 1–6 units mg−1 solid; ∼10 mg), and ADH (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 369 units mg−1 solid; ∼20 mg) were added. All chemicals were acquired from Sigma–Aldrich.

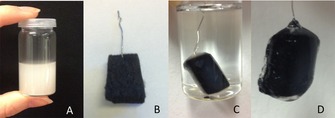

The carbon felt electrode was soaked with the alginate–silicate hybrid gel and kept in 0.2 m CaCl2 solution for 20 min for precipitation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Immobilization of enzymes in alginate–silicate hybrid gel for the application on a carbon felt‐based working electrode. Preparation of an alginate–silicate gel mixture (A). Blank carbon felt electrode (B) that is soaked with the alginate–silicate mixture and precipitated in CaCl2 (C). Alginate‐covered carbon felt electrode after precipitation (D).

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical measurements were performed using a JAISLE Potentiostat‐Galvanostat IMP 88 PC using Pt foil as counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl (3 m KCl) reference electrode, which was commercially obtained from BASI. A 0.05 m phosphate buffer solution with a pH value of 7.6 served as electrolyte. All electrochemical experiments were carried out in a two‐compartment cell with 25 mL liquid volume for both anode and cathode compartment. Anode and cathode compartment were separated by a frit (Figure 1) to avoid reoxidation of the reduction product. Electrolysis experiments were performed under potentiostatic conditions at −1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 4 h after saturating with N2 or CO2 for 30 min.

Analysis

Samples for analytical measurements were obtained using a syringe from the liquid phase and injected into the liquid injection gas chromatograph (LGC) using an autosampler (Thermo Scientific, Trace 1310, TR‐Wax column 30 m×0.32 mm ID ×0.50 μm film, flame ionization detector). The amount of methanol generated was determined by analyzing the liquid phase by means of LGC. The liquid samples were also investigated using capillary ion chromatography to detect formate (Dionex ICS 5000, conductivity detector, AG19 as guard column, capillary HPCL (CAP), 0.4×50 mm pre‐column; hydroxide‐selective anion‐exchange column AS19, CAP, 0.4×250 mm main column with KOH as eluent for isocratic chromatography). Further gas samples of the head space from the cathode compartment were analyzed before and after electrolysis for H2 evolution in gas chromatography using a Thermo Scientific Trace GC Ultra gas chromatograph using N2 as carrier gas.

Acknowledgements

Financial support by the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF) within the Wittgenstein Prize (Z222‐N19), FFG within the project CO2TRANSFER (848862) and REGSTORE project, which was funded under the EU Programme Regional Competitiveness 2007–2013 (Regio 13) with funds from the European Regional Development Fund and by the Upper Austrian Government.

S. Schlager, L. M. Dumitru, M. Haberbauer, A. Fuchsbauer, H. Neugebauer, D. Hiemetsberger, A. Wagner, E. Portenkirchner, N. S. Sariciftci, ChemSusChem 2016, 9, 631.

References

- 1. Aresta M., Forti G., Carbon Dioxide as a Source of Carbon: Biochemical and Chemical Uses, Springer, Dordrecht, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aresta M., Carbon Dioxide as Chemical Feedstock, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Olah G. A., Goeppert A., Prakash G. K. Surya, Beyond Oil and Gas: The Methanol Economy, 2nd ed., Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liu C.-J., Mallinson R. G., Aresta M., Utilization of Greenhouse Gases, 1st ed., American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aresta M., Carbon Dioxide Recovery and Utilization, Kluwer, Dordrecht, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nocera D., Acc. Chem. Res. 2012, 45, 767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Surendranath Y., Bediako D. K., Nocera D. G., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 15617–15621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kaneko M., Ochura I., Photocatalysis: Science and Technology, Springer, Heidelberg, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kalyanasundaram K., Graetzel M., Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2010, 21, 298–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Obert R., Dave B. C., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 12192–12193. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Pastore C., Environ. Chem. Lett. 2005, 3, 113–117. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Xu S.-W., Lu Y., Li J., Jiang Z.-Y., Wu H., Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 4567–4573. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bandi A., Specht M., Weimer T., Schauber K., Energy Convers. Manage. 1995, 36, 899–902. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cosnier S., Deronzier A., Moutet J.-C., J. Mol. Catal. 1988, 45, 381–391. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mizuno T., Naitoh A., Ohta K., J. Electroanal. Chem. 1995, 391, 199–201. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Benson E. E., Kubiak C. P., Sathrum A. J., Smieja J. M., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 89–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bassegoda A., Madden C., Wakerley D. W., Reisner E., Hirst J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 15473–15476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Aydin R., Köleli F., Synth. Met. 2004, 144, 75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smieja J. M., Sampson M. D., Grice K. A., Benson E. E., Froehlich J. D., Kubiak C. P., Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 2484–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cole E. B., Lakkaraju P. S., Rampulla D. M., Morris A. J., Abelev E., Bocarsly A. B., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11539–11551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baruch M. F., J. E. Pander III , White J. L., Bocarsly A. B., ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3148–3156. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuhl K. P., Hatsukade T., Cave E. R., Abram D. N., Kibsgaard J., Jaramillo T. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 14107–14113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Amao Y., Shuto N., Res. Chem. Intermed. 2014, 40, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Garcia-Martinez J., Nanotechnology for the Energy Challenge, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heichal-Segal O., Rappoport S., Braun S., Bio/Technology 1995, 13, 798–800. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aresta M., Quaranta E., Liberio R., Dileo C., Tommasi I., Tetrahedron 1998, 54, 8841–8846. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Aresta M., Dibenedetto A., Rev. Mol. Biotechnol. 2002, 90, 113–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lu Y., Jiang Z.-Y., Xu S.-W., Wu H., Catal. Today 2006, 115, 263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dibenedetto A., Stufano P., Macyk W., Baran T., Fragale C., Costa M., Aresta M., ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 373–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Addo P. K., Arechederra R. L., Waheed A., Shoemaker J. D., Sly W. S., Minteer S. D., Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2011, 14, E9–E13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kuwabata S., Tsuda R., Yoneyama H., J. Chem. Soc. 1994, 116, 5437–5443. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reda T., Plugge C. M., Abram N. J., Hirst J., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10654–10658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]