Abstract

PURPOSE

We employed user-centered design to refine a prototype of the eyeGuide, a novel, tailored behavior change program intended to improve medication adherence among glaucoma patients.

PATIENTS

Glaucoma patients ≥ age 40 prescribed ≥1 glaucoma medication were included.

METHODS

The eyeGuide consists of tailored educational content and tailored testimonials in which patients share how they were able to overcome barriers to improve their medication adherence. A hybrid of semi-structured diagnostic and pre-testing interviews were used to refine the content of the eyeGuide. Purposeful sampling was used to recruit a study population representative of the glaucoma patient population. Interviews were conducted until thematic saturation was reached. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three researchers analyzed the transcripts, generated a codebook and identified key themes using NVivo 10.0 to further refine the eyeGuide.

RESULTS

Twenty-one glaucoma patients were interviewed; mean age 72 ± 12.4 years, five (24%) African-Americans, nine (43%) with poor self-reported adherence, ten (47.6%) ≥ age 75, ten (47.6%) with poor vision and nine (42.9%) women. Qualitative analysis identified five important themes for improving glaucoma self-management: social support, patient-provider relationship, medication routine, patients’ beliefs about disease and treatment, and eye drop instillation. All participants expressed satisfaction with in-person delivery of the eyeGuide and preferred this to a web-based module. Participant feedback resulted in revised content.

CONCLUSIONS

User-centered design generated improvements in the eyeGuide that would not have been possible without patient input. Participants expressed satisfaction with the tailored content.

Keywords: Glaucoma, patient education, tailored health education, user centered design

INTRODUCTION

Globally, glaucoma is the leading cause of irreversible blindness.1 Glaucoma disproportionately affects the elderly; in the United States, the prevalence of glaucoma increases from about 2% among those over the age of 402 to 10.3% among people 75 and older.3-4 Because the number of adults over the age of 75 will more than double between 2010 and 2050,5 the number of people living with glaucoma in the U.S. will increase substantially.

Despite the availability of effective medications to treat glaucoma,6-8 glaucoma remains the third leading cause of blindness in the U.S.9 and disproportionately affects Latinos and African Americans.10-11 One important reason that glaucoma continues to cause vision loss is poor medication adherence. At least one-third and potentially up to 80% of glaucoma patients are poorly adherent,12-14 with approximately two-thirds of glaucoma patients failing to return consistently for follow-up visits.15 Patients with poor adherence to glaucoma medications have worse outcomes, with more severe visual field loss compared to adherent patients.16-18

Most of the successful interventions to improve medication adherence among glaucoma patients have employed individualized approaches through one-on-one counseling.19 This builds on a significant body of evidence demonstrating the benefits of interventions that ‘tailor’ health messages20 by individualizing the “information and behavior change strategies to reach each person based on characteristics unique to that person.”21 Computer software can tailor the content each individual receives based on personal data like socio-demographic characteristics, health condition, electronic health record data, and survey responses. Tailored educational content can be delivered through a variety of methods: in a web-based module, in print or in-person. Because glaucoma affects an older population who may not be as tech-savvy,22 we explored patient preferences for mode of communication.

The purpose of this study was to pilot test and refine the prototype of the eyeGuide, a novel, tailored behavior change program for glaucoma patients. The eyeGuide's content is individualized to each patient's medical record and it addresses barriers to optimal meditation adherence by sharing tailored testimonials from patients who have overcome challenges with medication adherence. The objectives of this study were to: 1) Employ user centered design to develop and refine the content of the eyeGuide and 2) elicit patient preferences about whether the intervention should be delivered in-person or over the web.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population

Participants were recruited from an academic glaucoma clinic at the University of Michigan. Eligibility criteria for study inclusion were age ≥40, diagnosis of primary open-angle glaucoma (ICD-9 codes 365.1, 365.10, 365.11, 365.12, 365.15), prescribed ≥1 glaucoma medication, and had an office visit with a University of Michigan glaucoma specialist between May 2013 and April 2014. Exclusion criteria included diagnosis of cognitive impairment (e.g. dementia), diagnosis of severe mental illness (e.g. schizophrenia), need for assistance with activities of daily living, living in an institution full time, and need for an interpreter. A letter was mailed to eligible participants to allow them to opt out of the study. Those who did not opt out were contacted by telephone. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan approved this study. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were contacted and their glaucoma medication adherence was assessed with the 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS-8) adapted for glaucoma.23-24 Purposeful sampling was used to recruit similar numbers of adherent and non-adherent glaucoma patients as defined by the MMAS-8, older (≥ age 75) and younger (<age 75) patients, men and women, patients with good and poor vision, and at least one-quarter African-American participants, as African-Americans are at increased risk for developing glaucoma10 and are less likely to adhere to treatment.15,18,25 We defined poor vision as best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) <20/40 or mean deviation (MD) on Humphrey Visual Field 24-2 <−6.0DB in the better seeing eye. We used U.S. Census data to estimate median income level by taking the average of the income values listed for each participant's race and age, both specific to the participant's zip code.26 These recruitment strategies were used to gather input from a diverse group of patients to reflect the broad range of patients who might use the eyeGuide in general practice. This represents user-centered design, a method that incorporates the end-user's feedback in an iterative fashion to ensure that the program is perceived as helpful and easy to understand.27

The eyeGuide

The eyeGuide consists of two tailored components: glaucoma education and patient testimonials. Bullet points and images were used according to the Center for Disease Control's (CDC) Clear Communication Index for improving health communication,28 and all text was written at ≤8th grade reading level as determined by Flesch-Kincaid software on Microsoft Word 2010. Text was written using the principles of motivational interviewing (MI) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT). MI is a counseling technique that is consistent with SDT and is designed to strengthen an individual's motivation and commitment to change a health behavior by engaging in a discussion on their values, goals, and barriers to change29; MI has been found to be effective in improving chronic disease self-management.30 Consistent with MI and SDT, the eyeGuide interviewer obtained permission from the subject before presenting a new section and ended each section with questions exploring the subject's feelings on the information. For example, after presenting the subject's optic disc photographs, the interviewer said, “Some people feel overwhelmed and upset after seeing their test results, and others find it helpful to understand why their eyesight is the way it is. How does seeing your test results make you feel?” Ultimately, the eyeGuide is designed to support a discussion between a patient and a health care provider trained in MI to improve the patient's motivation to adhere to their glaucoma medications.

Tailored Glaucoma Education

The tailored glaucoma content presented background information based on the subject's type of glaucoma and severity of disease, explained each individual's test results including their disc photographs and Humphrey Visual Fields, and provided customized medication instructions based on the subject's medical record. For example, subjects were shown an image of their optic nerves compared to a healthy optic nerve and the differences were explained. These messages reiterated information presented during the patient's visit with the physician but used simpler language, more analogies and audio-visual aids based on CDC Clear Communication recommendations.28

Tailored Patient Testimonials

The tailored testimonials were written as narratives in which another glaucoma patient—who is age, gender and race-matched to the patient—shared how they were able to overcome a barrier to achieve optimal glaucoma medication adherence. We chose this strategy because narratives from a person similar to the subject have been shown to significantly decrease the perceived severity of a shared barrier to health behavior change.31 To determine which testimonials would be presented to the participant, a questionnaire was administered at the beginning of the interview. The questionnaire asked subjects whether they experienced any of the following 17 barriers to taking their glaucoma medications as prescribed: side effects, cost, doctor-patient relationship, difficulty instilling eye drops, difficulty with complicated medication schedule, forgetfulness, skepticism that medication is effective, skepticism that glaucoma causes vision loss, life stress, poor knowledge, poor confidence, discomfort taking drops in front of family members, discomfort taking drops in public, fear of addiction, trouble getting refills after running out of medication too early, trouble taking drops when away from home, and trouble taking drops while traveling.23 The questionnaire also assessed the patient's cellphone and internet use to tailor the testimonials on technology usage. Subjects were presented with testimonials corresponding to each barrier they identified. Mismatched testimonials were presented to five subjects.

Interviews

Semi-structured interviews lasting 1-2 hours were conducted between June and August 2014. Interviews were a hybrid of pre-testing and diagnostic interviews. Pre-testing was done to elicit patients’ reactions to the content in order to refine it. The interviews were also diagnostic because we explored patients’ views on barriers to glaucoma medication adherence in an open-ended fashion to evaluate whether the eyeGuide needed to be tailored on additional content domains. Because half of the participants had poor vision, the interviewer read all of the educational material aloud while patients followed along with a printed version.

After presenting each section of the program, the interviewer used a semi-structured interview guide based in cognitive debriefing to elicit feedback about the section.32-34 The interview guide also included broad questions at the end about the overall acceptability of the intervention, whether the subject had additional barriers to optimal glaucoma medication adherence, and whether the subject would rather use the program independently on a computer or with a paraprofessional at the doctor's office. The interviewer took detailed notes on participants’ feedback during the interview, and the session was audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Refining the eyeGuide

The study team met throughout the study period to discuss subjects’ feedback and common themes that arose during the interviews. If >1 participant demonstrated poor understanding or strong dislike of an educational message or questionnaire item, the content was refined and a revised message was presented to subsequent participants. If multiple subjects suggested an additional barrier to medication adherence or a strategy for overcoming a barrier, the materials were revised to incorporate these suggestions. In this way, the eyeGuide's content was refined in an iterative and self-correcting process.33 Interviews were concluded when all significant shortcomings had been resolved and thematic saturation was reached. We defined thematic saturation as 3 successive interviews in which no further substantive suggestions were made.

Analysis

The transcripts were coded using standard content analysis methods with NVivo 10.0. Thematic codes were agreed upon by consensus and a codebook was developed. Transcripts were then re-analyzed using the codebook. Key themes were identified by consensus and the educational program was refined further.

RESULTS

Of the 209 subjects who met inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10 opted out of participating in the study during initial screening and 199 were eligible for participation. Twenty-one glaucoma patients participated in interviews (Table 1). Twelve were adherent to their medications and 9 were not by the MMAS-8. The average age of participants was 72 ± 12.4 years of age, with a range of 44 to 89 years old. Eleven patients (52.4%) were younger (<75 years old) and 10 (47.6%) were older (≥75). Of the older patients, 4 (19.0%) were elderly (≥85 years old). Nine participants were women (42.9%) and 12 were men (57.1%). Fifteen (71.4%) were white, 5 (23.8%) were black, and 1 (4.8%) was South Asian. The average income of participants was $56,751 per year, with a range of $34,243 – $93,142 per year. The visual acuity ranged from 20/20 to hand motion and the mean deviation on Humphrey Visual Field testing ranged from +0.68dB to −30.01dB. Ten (47.6%) participants had poor vision (Table 2).

Table 1.

Study participants' demographic variables

| Age | |

| Age range, yr | 44-89 |

| Mean age (SD), yr | 72.0 (12.4) |

| 44-74, n (%) | 11 (52.4) |

| 75-84, n (%) | 6 (28.6) |

| 85-89, n (%) | 4 (19.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Women | 9 (42.9) |

| Men | 12 (57.1) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White or Caucasian | 15 (71.4) |

| Black or African American | 5 (23.8) |

| Asian Indian | 1 (4.8) |

| Medication adherence variables | |

| MMAS-8 score range | 0-9 |

| Mean score (SD) | 1.8 (2.3) |

| Adherent (MMAS-8 score ≤1), n (%) | 12 (57.1) |

| Non-adherent (MMAS-8 score ≥2), n (%) | 9 (42.9) |

| Medication variables | |

| Number of glaucoma medications range | 1-5 |

| Mean number of glaucoma medications (SD) | 2.3 (1.1) |

| Prescribed 1 glaucoma medication, n (%) | 6 (28.6) |

| Prescribed 2 glaucoma medications, n (%) | 5 (23.8) |

| Prescribed 3 glaucoma medications, n (%) | 9 (42.9) |

| Prescribed 4 glaucoma medications, n (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Prescribed 5 glaucoma medications, n (%) | 1 (4.8) |

| Median income | |

| Income range | $34,243 – $93,142 |

| Mean income | $56,751 |

| Use of a cellphone | |

| Cellphone | 12 (57.1) |

| No cellphone | 9 (42.9) |

| Use of internet | |

| Yes | 15 (71.4) |

| No | 6 (28.6) |

Table 2.

Study participants’ visual acuity

| Subject | Test Date | Visual acuity L | logMar left | Visual Acuity R | logMar R | Visual mean deviation L | Visual mean deviation R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7/22/2014 | 20/30 | 0.2 | 20/80 | 0.6 | −5.83 | −7.8 |

| 2 | 10/3/2014 | 20/20 | 0 | 20/20 | 0 | −11.45 | −10.32 |

| 3 | 7/23/2014 | 20/40 | 0.3 | 20/40 | 0.3 | −3.89 | +0.68 |

| 4 | 6/3/2014 | 20/30 | 0.2 | 20/20 | 0 | GVF temporal island of vision remaining | −4.08 |

| 5 | NLP | HM | |||||

| 6 | 9/17/2014 | 20/125Ecc | 0.8 | 20/25 | 0.1 | −31.01 | −29.87 |

| 7 | 9/15/2014 | CF @ 1’ | None on file | 20/60 | 0.5 | unable | −17.25 |

| 8 | 7/11/2014 | 20/60 | 0.5 | 20/30 | 0.2 | −11.69 | −13.22 |

| 9 | 10/31/2014 | 20/50 | 0.4 | 20/50 | 0.4 | −0.66 | −1.81 |

| 10 | 6/12/2014 | 20/30 | 0.2 | 20/20 | 0 | −3.93 | −16.79 |

| 11 | 9/18/2014 | 20/60 | 0.5 | NLP | −16.68 | unable | |

| 12 | 7/8/2014 | 20/125 | 0.8 | 20/60 | 0.5 | −8.25 | −2.37 |

| 13 | 12/12/2014 | 20/40 | 0.3 | 20/20-2 | 0 | −20.71 | −2.81 |

| 14 | 9/17/2014 | 20/200 | 1 | 20/30 | 0.2 | −20.59 | −1.11 |

| 15 | 8/29/2014 | 20/20 | 0 | 20/20 | 0 | −1.1 | −7.38 |

| 16 | 8/8/2014 | 20/20 | 0 | 20/20 | 0 | −7.99 | −3.99 |

| 17 | 7/17/2014 | 20/20 | 0 | 20/25 | 0.1 | −0.95 | −0.98 |

| 18 | 4/17/2014 | 20/20 | 0 | 20/25 | 0.1 | −0.77 | −0.36 |

| 19 | 12/3/2014 | 20/80 | 0.6 | 20/40 | 0.3 | −18.14 | −16.42 |

| 20 | 3/27/2014 | 20/40 | 0.3 | 20/40 | 0.3 | −20.57 | −8.09 |

| 21 | 8/6/2014 | 20/40 | 0.3 | 20/30 | 0.2 | −3.85 | −6.45 |

Thematic Saturation

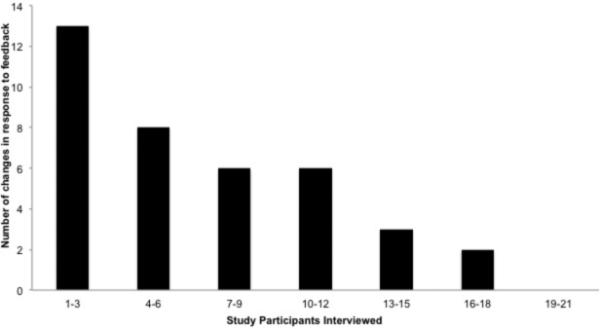

As the study period progressed, participants made fewer and fewer novel comments, and constructive criticism of the program decreased markedly. This is illustrated in Figure 1, which shows that feedback leading to changes in the program decreased over the course of the project. Interviews 17-21 did not generate any substantive changes. Thus, we met our definition of thematic saturation by interview 19 and concluded the interviews after interview 21.

Figure 1.

Study participants’ feedback leading to eyeGuide content changes

Content Analysis

The transcripts were analyzed to identify the areas that patients perceived as most important in managing their glaucoma. The number of participants who mentioned each theme was quantified. Five major themes emerged (Table 3, illustrative quotes for each theme). (1) The role of social support (7/21 participants) and how friends and family helped with instilling or remembering to take glaucoma medications. (2) The role of the patient-provider relationship (18/21 participants); some patients followed their doctors’ orders even without a complete understanding of glaucoma, while others were frustrated that their doctors did not have enough time to educate them. (3) The role of integrating medication-taking into the daily routine (21/21 participants). Every subject commented on how s/he implements or needs to implement medication taking into his/her daily routine. (4) The importance of discussing disease and medication beliefs (21/21 participants). All 21 participants commented on their beliefs about glaucoma and its treatment, which were widely variable. (5) Teaching eye drop instillation (14/21 participants); 66% of participants shared either their difficulties with instillation or techniques that have helped them with eye drop instillation.

Table 3.

Sample statements illustrating each theme

| Major Themes and Examples | Number of participants expressing theme | Number of times referenced |

|---|---|---|

|

The role of social support • I also think it's helpful if you teach your family to put in the drops... Because sometimes – I mean especially when you are older, you may – it just may be easier to let somebody else do it.” • “Okay. The question – the first question, ‘do you have trouble putting in your eye drops?’ Well, typically my wife does it.” |

7 | 25 |

|

Patient-provider relationship • [Reading the questionnaire] “Do you feel like you have a good understanding of why you should take drops to treat your glaucoma? [Laughing] No! Because the doctor said so!” • “...we're old enough that there was once doctors visited you at home and there was one physician that did everything. Now they are specialists, and I'm not convinced that the specialists are aware of what the other specialist has done and why.” • There are times when I am sometimes concerned as to whether or not I'm getting the proper treatment at any given time, because of the busyness [of the doctors].” |

18 | 61 |

|

Medication routine and action plan • “I'll show you what I keep it in. I put drops in my eyes first thing in the morning. This goes to bed with me at night and it is on the nightstand [gestures to small pouch that she keeps medication in]. I keep it just in this little bag. I have a clean kleenex in here. I put in three drops a day in and so I have two that I put in three times a day, and then the one that I put in before I go to bed. And I also have Natural Tears that I keep in here, the individual ones. So, everything I need is right in here.” • “What I need to do is post [a reminder] on my bathroom door, so it's on that door. “Go put your drops in your eyes.” |

21 | 97 |

|

Disease and medication beliefs • [Response to: Do you believe that glaucoma will really cause to lose vision?] “Well, because I've seen contrary things to that. That it won't affect your vision, and then also I've seen it you can lose your vision. So these are conflicting things that I've read.” |

21 | 111 |

|

Eye drop instillation • I was asked over and over, “isn't there anybody who could do it for you?” Well there isn't. You can't ask persons – people to keep on your schedule twice a day and pop in and give you an eye drop. So you have to learn to do that. And I did feel in the beginning that there could be a little bit more instructive help from tech people to – suggestions to help you do that, especially if you were having difficulty yourself for some reason. • The other thing is, I have a tendency to use too much because I don't feel like I have it [meaning successfully got it in the eye], so then I run out. |

14 | 30 |

|

Having a facilitator present the information improved the experience over a solely web-based program Participants could ask the facilitator questions • “I don't think I could become addicted to it, can you?” • “And do reading have an effect on [glaucoma]?” |

21 | 381 |

| Participants stated a preference for a facilitator • “Well I think a personal part of it is always a little bit better, more intimate and you can ask questions more easily. Sometimes it is hard to articulate a question, but if you're with someone, you can work around till you finally get to what it is you want to know.” |

||

|

Tailoring the educational information was useful Response to tailored health information: • “Since this is personal, it's meaningful. I mean, this is the first time that I've seen – actually a print out of that on a screen, any results. And that helps considerably.” • “I liked the images here. It always helps to... they say “One picture is worth a thousand words,” and I hadn't seen a picture of a healthy nerve, a healthy optic nerve, and I hadn't seen the pictures of my damaged optic nerve. I knew it had been damaged, but I like the visual approach.” |

21 | 346 |

| Responses to tailored testimonials: • “Well, I think it's good because it gives the patient a chance to see what other people are doing and if they have problems, how they corrected those problems. • “It makes it more human somehow to hear what other people – it's hard to find people who have glaucoma and to talk to other people. [It] really helps for me to compare some things with what people do.” |

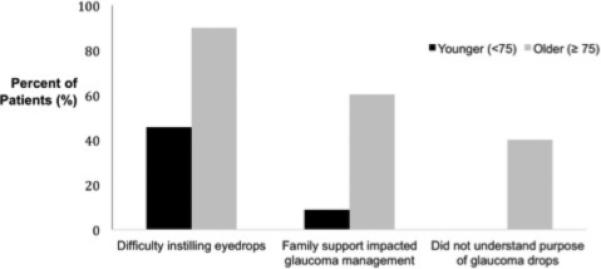

We found important differences between older and younger patients (Figure 2). Nearly every older patient (90%, 9/10) had difficulty instilling eye drops compared to approximately half of the younger patients (45%, 5/11). Older patients were much more likely to have their families involved in their glaucoma management than younger patients (1/11 [9%] younger patients versus 6/10 [60%] older patients). Additionally, 40% (4/10) of older patients said that they did not understand the purpose of their glaucoma medication yet took it to comply with their doctors’ instructions; none of the younger patients expressed this idea.

Figure 2.

Different barriers to medication adherence among older and younger study participants

A major area of difference among patients who were adherent to their medications and those who were not was their beliefs about treatment efficacy. Of the adherent individuals, 9/12 (75%) commented on treatment efficacy and expressed willingness to make sacrifices for their vision, had a plan about medication management, and were committed to following their doctors’ orders. For example one subject said, “My doctor tells me to do something, I do it!” Conversely, of the 9 non-adherent individuals, the 5 participants (55%) who commented on treatment efficacy reported a lack of trust in their physicians, trouble getting refills, challenges with drop instillation, and a desire not to let glaucoma treatment control their lives. For example, one subject said, “I will not stop doing what I'm doing in order to take [drops]. I will get to it when I can.”

In all of the interviews, patients expressed a preference for having the eyeGuide program delivered in-person instead of as a web-based module (Table 3). The importance of having the intervention delivered in-person was also evident when the research assistant reflected participants’ experiences back to them in order to affirm, clarify or support a behavior. For example, the research assistant said, “That sounds frustrating,” and, “It sounds like you have a really good routine that works for you.” By providing real-time, in-person feedback, the research assistant was able to support patients in improving their medication-taking behavior. In one interview, the research assistant suggested, “If you find that you're often times falling asleep on the couch, maybe you could have a Post-It Note on the TV remote [to remind you to take your drops] or something like that?” and the participant responded, “Yeah, see those are the things I hadn't thought about. I can do that!”

To determine if tailoring was important, five patients were presented with mismatched testimonials about barriers that did not apply to them. All five reported that the content was unhelpful. Some expressed frustration with the mismatched message. For example, “My honest reaction is this person [in the testimonial] is incredibly naïve... [hearing this message] would turn me off... [it] doesn't rub me right.” Others stated that they did not share the barrier discussed in the testimonial and did not understand how another person could have so much trouble with it. For example, one participant responded to a mismatched message by saying, “I can't relate! Frankly, it sounds stupid.”

Overall, both the adherent and non-adherent patients reported great satisfaction with the tailored intervention (Table 3). All participants expressed interest in learning more about glaucoma, demonstrated their engagement by asking follow-up questions, and commented on how helpful the program was and how much they learned. For example, subjects said, “I'm pleased that I attended this session. It's very helpful,” and, “I think I have learned a few things, and I think it would be very valuable to people.”

DISCUSSION

Overall, we found that each subject had a unique experience with glaucoma and a personal story s/he wanted to tell; being able to tell this story built rapport with the interviewer. Patients resonated with the tailored information and appreciated that their personal test results were being explained—“this is personal, it's meaningful.” Participants valued hearing how similar patients overcame their barriers to optimal glaucoma medication adherence—“[it] makes it more human somehow to hear what other people [do].” People expressed appreciation for having the educational session occur in-person as opposed to completing a module online.

We revised the eyeGuide based on patients’ feedback. For example, two participants reported that the testimonial about instilling drops in public made the patient sound embarrassed about using drops in front of others; the message was revised and subsequent participants gave it positive feedback. Additionally, we identified two new barriers to medication adherence—trouble getting refills after running out of medication too early and trouble taking medication while traveling—and we created testimonials to address these issues.

In our qualitative analysis of the transcribed interviews, we found that many older patients rely on support systems to help manage their glaucoma. Thus, future iterations of the eyeGuide will include social support as a tailoring variable. Older patients also had a harder time with eye drop instillation. Going forward, we will address this by teaching eye drop instillation as part of the eyeGuide behavior change program. We found that adherent and non-adherent patients differ greatly in their beliefs about glaucoma and its treatment; each individual's views will need to be discussed in detail in a counseling session to overcome any misinformation or misgivings a patient may have about taking glaucoma medications. To elicit patients’ beliefs about their disease, strengthen their resolve to change their behavior, and teach eye drop instillation, it will be very important to have this educational module delivered in-person instead of via the internet.

Highly tailored education has been shown to improve outcomes in a wide range of health behaviors such as obtaining mammograms,35 increasing levels of physical activity,36 and quitting smoking.37 In-depth tailoring has also been shown to improve outcomes in chronic diseases ranging from asthma38-39 to diabetes.40-41 Additionally, using patient narratives—accounts of other patients’ experiences—has been shown to decrease the perceived severity of a shared barrier to health behavior change.31

We found that our tailored material invoked self-referential thinking. Self-referential thinking is a concept from the Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion.42 This model indicates that when individuals are truly cognitively engaged, they will apply what they have learned to their own situation. For example, when a subject was asked what he thought about a testimonial from “Joe,” another glaucoma patient, the subject responded, “I am thinking about me. I think I'm a lot like Joe. He's starting to think, ‘Well, you're getting older, you don't want to lose vision.’ Even though I am no longer working, I still want good vision. Now I am concerned about glaucoma....” Because self-referential thinking has been shown to lead to more sustained behavior changes,21,43 we believe that highly-tailored interventions like the eyeGuide may be particularly effective in improving glaucoma medication adherence.

As this was a pilot study, there were a number of limitations inherent in the design. The results are not generalizable to the general glaucoma population due to the limited number of subjects enrolled. Purposeful sampling, however, was used to include patients from a wide variety of socio-demographic backgrounds and a wide variety of visual ability in an attempt to gain a more generalizable perspective. Additionally, the purpose of this qualitative study was to engage patients in the development of a behavior change program and generate hypotheses. The user-centered design led to improvements in the program that would not have been possible without patient input. The patients interviewed also overwhelmingly supported the idea that glaucoma patients would benefit from in-person, tailored education in addition to the information they receive from their ophthalmologists.

Interventions that improve patient satisfaction with glaucoma care will be an integral part of transforming eye care delivery from a provider-centered to a patient-centered model. Health insurers are looking to patient satisfaction as an important metric for evaluating the quality of care that health care organizations provide.44 Implementing personalized behavior change programs such as the eyeGuide into clinical practice has the potential to greatly improve patient satisfaction with their glaucoma care.

Acknowledgements

Supported by grants from the National Eye Institute Michigan Vision Clinician-Scientist Development Program (K12EY022299). The sponsor or funding organization had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest for PANC, OK, CM, MH. PPL is a consultant for Genentech and Novartis, and has stock in Pfizer, Merck, GSK, Medco Health Solutions, Vital Springs Health Technologies.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) [Dec 22, 2013];Prevention of Blindness and Visual Impairment. [WHO web site]. Causes of blindness and visual impairment. Available at: http://www.who.int/blindness/causes/en/index.html.

- 2.The Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group Prevalence of Open-Angle Glaucoma Among Adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(4):532–538. doi: 10.1001/archopht.122.4.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ryskulova A, Turczyn K, Makuc DM, et al. Self-reported age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in the United States: results of the 2002 national health interview survey. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:454–461. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein R, Klein BE. The prevalence of age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in aging: current estimates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(14):ORSF5–ORSF13. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Census Bureau [February 15, 2015];National population projections. [US Census Web site] Available at: http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/summary tables.html.

- 6.The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS) 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration. The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(4):429–440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00538-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(6):701–713. doi: 10.1001/archopht.120.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leske MC, Heijl A, Hussein M, et al. Factors for glaucoma progression and the effect of treatment: the early manifest glaucoma trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(1):48–56. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–267. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, et al. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey. JAMA. 1991;266(3):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Varma R, Ying-Lai M, Francis BA, et al. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension in Latinos: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olthoff CM, Schouten JS, van de Borne BW, et al. Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(6):953–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz GF, Quigley HA. Adherence and persistence with glaucoma therapy. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53(Suppl1):S57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kass MA, Gordon M, Morley RE, Jr, et al. Compliance with topical timolol treatment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103(2):188–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74225-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami Y, Lee BW, Duncan M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in adherence to glaucoma follow- up visits in a county hospital population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):872–878. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossi GC, Pasinetti GM, Scudeller L, et al. Do adherence rates and glaucomatous visual field progression correlate? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2011;21(4):410–414. doi: 10.5301/EJO.2010.6112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sleath B, Blalock S, Covert D, et al. The relationship between glaucoma medication adherence, eye drop technique, and visual field defect severity. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(12):2398–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart WC, Chorak RP, Hunt HH, et al. Factors associated with visual loss in patients with advanced glaucomatous changes in the optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;116(2):176–181. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71282-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman-Casey PA, Weizer JS, Heisler M, et al. Systematic review of educational interventions to improve glaucoma medication adherence. Seminars in Ophthalmology. 2012;28(3):191–201. doi: 10.3109/08820538.2013.771198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neville LM, O'Hara B, Milat AJ. Computer-tailored dietary behaviour change interventions: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2009;24(4):699–720. doi: 10.1093/her/cyp006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins R, Kreuter M, Resnicow K, et al. Understanding Tailoring in Communicating About Health. Health Education Research. 2008;23:454–66. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saeedi OJ, Luzuriaga C, Ellish N, et al. Potential Limitations of E-mail and Text Messaging in Improving Adherence in Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(5):e95–e102. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0000000000000150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newman-Casey PA, Robin AL, Blachley T, et al. The Most Common Barriers to Glaucoma Medication Adherence: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Ophthalmology. Jul;122(7):1308–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morisky DE, Krousel-Wood Ang, A, et al. Predictive Validity of A Medication Adherence Measure in an Outpatient Setting. J Clinical Hypertension. 2008;10(5):348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Dreer LE, Girkin C, Mansberger SL. Determinants of medication adherence to topical glaucoma therapy. J Glaucoma. 2012;21(4):234–240. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e31821dac86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Census Bureau [February 20, 2015];2008-2012 American Community Survey. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov.

- 27.De Vito Dabbs A, Myers BA, Mc Curry KR, et al. User-centered design and interactive health technologies for patients. Comput Inform Nurs. 2009;27(3):175–183. doi: 10.1097/NCN.0b013e31819f7c7c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [December 28, 2014];CDC Clear Communication Index User Guide. 2013 Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/pdf/clear-communication-user-guide.pdf.

- 29.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2012. pp. 1–403. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, et al. Motivational Interviewing a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J General Practice. 2005;55(513):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dillard A, Fagerlin A, Cin SD, et al. Narratives that Address Affective Forecasting Errors Reduce Perceived Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;71(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Willis G. Cognitive interviewing in practice: think-aloud, verbal probing, and other techniques. Cognitive Interviewing. SAGE Publications Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2005. pp. 42–64. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leidy NK, Vernon M. Perspectives on patient-reported outcomes: content validity and qualitative research in a changing clinical trial environment. Pharmaco Economics. 2008;26(5):363–370. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200826050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(3):229–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1023254226592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skinner CS, Strecher VJ, Hospers H. Physicians’ recommendations for mammography: do tailored messages make a difference? Am J Public Health. 1994;84(1):43–49. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bock BC, Marcus BH, Pinto BM, et al. Maintenance of physical activity following an individualized motivationally tailored intervention. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23(2):79–87. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2302_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strecher VJ, Marcus A, Bishop K. A randomized controlled trial of multiple tailored messages for smoking cessation among callers to the cancer information service. J Health Communication. 2005;10(1):105–118. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joseph CL, Peterson E, Havstad S, et al. A web-based, tailored asthma management program for urban African-American high school students. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(9):1, 888–95. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1244OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thoonen BP, Schermer TR, Jansen M, et al. Asthma education tailored to individual patient needs can optimise partnerships in asthma self-management. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47(4):355–60. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carter BM, Barba B, Kautz DD. Culturally tailored education for African Americans with type 2 diabetes. MedSurg Nursing. 2013;22(2):105–9. 123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spencer MS, Rosland AM, Kieffer EC, et al. Effectiveness of a community health worker intervention among African American and Latino adults with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(12):2253–60. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.300106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petty RE, Cacioppo JT. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1986;19:123–192. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petty RE. Creating strong attitudes: two routes to persuasion. In: Backer TE, David SL, Soucey G, editors. Reviewing the behavioral science knowledge base on technology transfer. Vol. 155. National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) Research Monograph; Rockville MD: pp. 209–224. Publication N. 94-40350. [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Department of Health and Human Services [December 16, 2015];Annual Progress Report to Congress, National Strategy for Quality Improvement in Health Care. 2012 2012 Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/reports/annual-reports/nqs2012annlrpt.pdf. [Google Scholar]